Abstract

Minocycline is broadly protective in neurologic disease models featuring cell death and is being evaluated in clinical trials. We previously demonstrated that minocycline-mediated protection against caspase-dependent cell death related to its ability to prevent mitochondrial cytochrome c release. These results do not explain whether or how minocycline protects against caspase-independent cell death. Furthermore, there is no information on whether Smac/Diablo or apoptosis-inducing factor might play a role in chronic neurodegeneration. In a striatal cell model of Huntington's disease and in R6/2 mice, we demonstrate the association of cell death/disease progression with the recruitment of mitochondrial caspase-independent (apoptosis-inducing factor) and caspase-dependent (Smac/Diablo and cytochrome c) triggers. We show that minocycline is a drug that directly inhibits both caspase-independent and -dependent mitochondrial cell death pathways. Furthermore, this report demonstrates recruitment of Smac/Diablo and apoptosis-inducing factor in chronic neurodegeneration. Our results further delineate the mechanism by which minocycline mediates its remarkably broad neuroprotective effects.

Minocycline, a semisynthetic tetracycline, has demonstrated remarkably broad neuroprotective properties in experimental models of ischemic stroke, Huntington's disease (HD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), traumatic brain injury, multiple sclerosis, and Parkinson's disease (1-6). The mechanisms of minocycline-mediated neuroprotection have been demonstrated to result, at least in part, from inhibiting release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria in a transgenic mouse model of ALS (3). Additional effects have been ascribed to minocycline that include inhibition of caspase-1, -3, and iNOS transcriptional up-regulation and activation, reactive microgliosis, and activation of p38MAK (1-3, 6, 7). All inhibitory properties of minocycline, other than microgliosis, likely result from inhibiting downstream events after cytochrome c release. Inhibition of reactive microgliosis is a direct effect of minocycline in vitro (7). At present, it is not clear whether in vivo inhibition of reactive microgliosis is a direct effect of minocycline or a secondary event resulting from inhibition of neuronal cell death. It is likely that the effect of minocycline on microglia in vivo is both relevant and important and results from a combination of both direct and indirect effects on microglia.

Mitochondria harbor molecules that, once released into the cytoplasm, trigger both caspase-dependent (cytochrome c and Smac/Diablo) and -independent [apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) and endonuclease G] cell death pathways (8-12). Binding of cytochrome c to Apaf-1 results in apoptosome-mediated caspase-9 activation (9). Activated caspase-9 can thereafter activate caspase-3. Smac/Diablo binds to caspase-3 inhibitors, leading to incremental caspase-3 activation (10, 13). In contrast to the above-mentioned caspase-dependent mediators of cell death, AIF and endonuclease G mediate cell death in a caspase-independent manner (11, 12, 14). At present, there is no published information on whether Smac/Diablo or AIF might play a role in mediating cell death in chronic neurodegeneration. In this report, we demonstrate that both caspase-independent and -dependent pathways are activated in vitro in striatal neuron cell death and in vivo in a mouse model of HD. Therefore, for effective blockade of downstream cell death events, inhibition of caspase-dependent and -independent pathways must be accomplished. Explaining its remarkably broad neuroprotective properties, we demonstrate that minocycline is the first drug, to our knowledge, that inhibits both caspase-independent and -dependent cell death pathways.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines and Apoptotic Stimulation. N548mu [nt1955-128] stable huntingtin ST14A cells and parental ST14A cells were cultured as described (15). Cells were shifted to the nonpermissive temperature of 37°C in serum-deprived medium (SDM) or treated with 10 ng/ml tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, 10 μM cycloheximide (CHX); 2 mM 3-nitropropionic acid (3-NP); or 50 μM etoposide for the indicated time with or without different concentrations of minocycline. Cell death was determined by the 3-(4,5)-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium, inner salt assay as described (16) (Promega). Minocycline and 3-NP were purchased from Sigma; TNF-α was purchased from Roche Molecular Biochemicals; and CHX and etoposide were purchased from Calbiochem.

Western Blot. Mutant huntingtin ST14A cells were shifted to the nonpermissive temperature of 37°C in SDM with or without minocycline. Cells were collected in lysis buffer [20 mM Tris, pH 8.0/137 mM NaCl/10% glycerol/1% Nonidet P-40/2 mM EDTA with 5 mM Na2VO4, protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Molecular Biochemicals)/0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride] on ice, centrifuged at 19,720 × g for 10 min at 4°C, and directly analyzed by Western blot. Mouse brain samples were lysed in RIPA buffer with protease inhibitors (3). Caspase-8 and -3 antibodies were purchased from PharMingen, caspase-9 antibody from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA), caspase-1 antibody from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, BID antibody from R & D Systems, β-actin antibody from Sigma, and histone H2A antibody from MBL (Watertown, MA). For analysis of cytosolic components, cytochrome c antibody was purchased from PharMingen, Smac/Diablo antibody from Novus Biologicals (Littleton, CO), and AIF antibodies from QED Bioscience, San Diego (for cells) and Sigma (for mice).

Fractionation of Cells and Tissue. Cell and tissue cytosolic fractionation was performed as described (3). Released cytochrome c, Smac, and AIF were analyzed by Western blot. Cyclosporin A was purchased from Sigma. For mitochondrial isolation, mitochondria treated with tBid or calcium were isolated from mouse brains as described (3). Liver mitochondria were isolated from 4- to 6-month-old male Fischer 344 Brown Norway F1 rats as described (3, 17). For preparation of nuclear extract, cell lysates were prepared as described (18).

Immunocytochemistry. ST14A cells were treated as indicated on chamber slides. The cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, 0.1 M glycine for 15 min, and 1% Triton X-100 for 30 min. Blocking was done in 5% BSA in PBS for 30 min. Cells then were incubated with antibodies to cytochrome c, Smac, or AIF, and incubated with Texas red- or FITC-conjugated secondary antibodies. Rhodamine 123 staining (Molecular Probes) (2 μM for 5 min) or Hoechst 33342 staining (Molecular Probes) (1:10,000 for 2-5 min) was performed. Deconvoluted images were taken with a Nikon ECLIPSE TE 200 fluorescence microscope and processed by using ip lab software (Spectra Services, Webster, NY).

Caspase Activity Assays. Cell extracts and enzyme assays were performed as described (19) and according to the manufacturer's instructions (CLONTECH). The ApoAlert caspase 8 fluorescent assay kit, including caspase-8 substrate Ac-IETD-3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole (AFC), was from CLONTECH; caspase-1 substrate Ac-YVAD-AFC and caspase-9 substrate Ac-LEHD-AFC were from Calbiochem; and caspase-3 substrate Ac-DEVD-AFC was from PharMingen. Released AFC was quantified in a Bio-Rad Versa Fluoro Meter (excitation at 400 nm and emission at 505 nm).

Permeability Transition (PT) Induction and Plate Reader Experiments. PT induction was assessed spectrophotometrically essentially as described (3, 17) by suspending 0.2 mg of mitochondrial protein at room temperature in 200 λ of 215 mM mannitol/71 mM sucrose/5 mM K-Hepes (pH 7.4) in the presence of 5 mM glutamate/5 mM malate.

Mice and Treatment. R6/2 mice (The Jackson Laboratory) were assigned randomly to treatment groups. For the mitochondrial studies, treatment began at 8.5 weeks of age. Mice were treated daily for 2 weeks with i.p. injections of either saline or 10 mg/kg minocycline hydrochloride in 0.5 ml of saline. Mice were killed and brains harvested at 10.5 weeks of age. Minocycline was prepared fresh daily. Experiments were in accordance with protocols approved by the Harvard Medical School Animal Care Committee.

Statistical Analysis. Densitometric quantification was performed by using the Quantity One Program (Bio-Rad). Statistical significance was evaluated by statview software by using the T test; P values <0.05 were considered significant as indicated (* in Figs. 1 and 5).

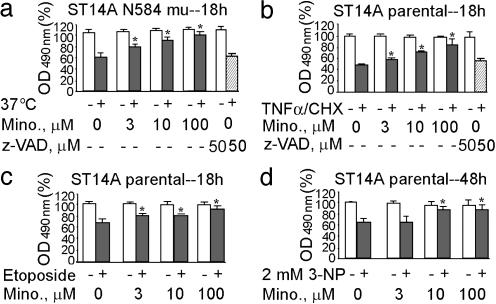

Fig. 1.

Minocycline inhibition of striatal neuronal cell death. N584 mutant huntingtin-stable ST14A cells (a) and ST14A parental cells (b-d) were treated at the nonpermissive temperature of 37°C in SDM for 18 h (a), TNF-α (10 ng/ml)/CHX (10 μM) for 18 h (b), etoposide (50 μM) for 18 h (c), and 3-NP (2 mM) for 48 h (d) in the presence (3, 10, or 100 μM) or absence of minocycline. Cell death was evaluated by the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium, inner salt assay and expressed as the percent of the control condition. The results are the mean ± SD of three independent experiments (*, P < 0.05). Empty bars indicate cells without apoptotic inducers. Solid bars indicate cells with apoptotic inducers. Hatched bars indicate cells with apoptotic inducers plus z-VAD.fmk. Mino represents minocycline-treated cells.

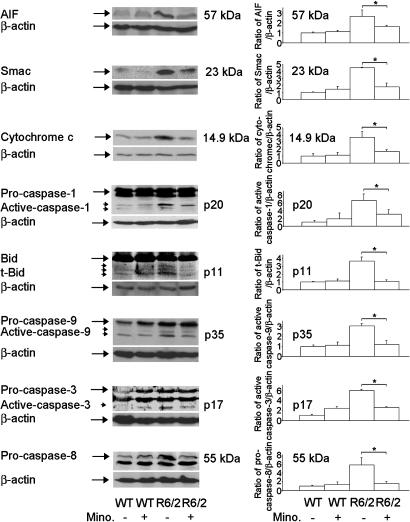

Fig. 5.

Minocycline inhibits AIF, Smac, and cytochrome c release, caspase activation, and Bid cleavage in R6/2 mice. Cytosolic fractions from 10.5-week-old R6/2 mice or wild-type mice treated with i.p. injections of saline or minocycline were analyzed by Western blot with AIF, Smac, and cytochrome c antibodies. Brain lysates from above mice were separated by SDS/PAGE and probed with caspase-1, -9, -3, and -8 and Bid antibodies. The same blot was reprobed with a β-actin antibody. Densitometry was performed to quantify each lane (n = 3 mice per condition, *, P < 0.05).

Results

Minocycline Blocks Release of Mitochondrial Cell Death Mediators in Striatal Neurons in Vitro. Given that minocycline is neuroprotective in a mouse model of HD (2), we investigated whether minocycline could inhibit polyglutamine-induced cell death in a striatal neuron cell line. ST14A cells are striatal neurons conditionally immortalized by transfection with a temperature-sensitive form of the simian virus 40 large T antigen. ST14A cells stably expressing a mutant huntingtin truncation (N548 mu) have been used as a cellular model of HD (15), therefore we used this paradigm to perform further mechanistic studies. As demonstrated (15), once shifted to a nonpermissive temperature, mutant huntingtin expressing ST14A cells die in a time- and polyglutamine-dependent manner. Minocycline significantly inhibited mutant huntingtin ST14A cell death (Fig. 1a). We then evaluated whether minocycline-mediated neuroprotection could be extended to other cell death paradigms. Minocycline inhibited cell death induced by TNF-α/CHX (cell death receptor pathway) (Fig. 1b), 3-NP (a mitochondrial toxin) (Fig. 1c), or by etoposide (DNA-damaging agent) (Fig. 1d). The best inhibitory effect of minocycline was on TNF-α/CHX-mediated apoptosis, and thus we used this paradigm, in addition to the mutant huntingtin-expressing cells, to perform further mechanistic studies. Surprisingly, the addition of z-VAD.fmk, a pan-caspase inhibitor, was not effective at inhibiting the shifting to a nonpermissive temperature-mediated mutant huntingtin ST14A cell death (Fig. 1a) or TNF-α/CHX-mediated parental striatal cell death (Fig. 1b). Lack of neuroprotection of z-VAD.fmk in striatal cell death suggests that caspase-independent pathways might play an important role in these paradigms. The efficacy of minocycline, in contrast to z-VAD.fmk, suggests that minocycline might potentially be blocking caspase-independent and -dependent cell death pathways.

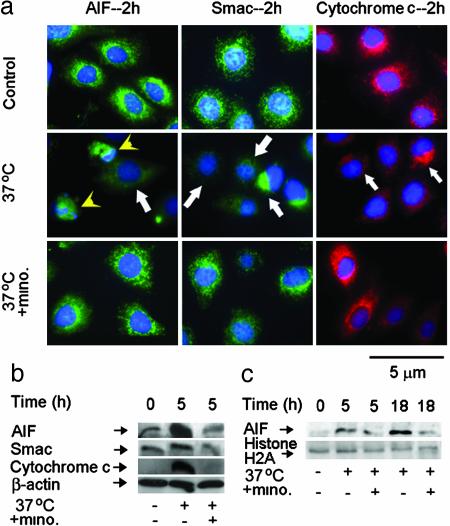

Mitochondria harbor within the intermitochondrial space cell death promoting factors such as cytochrome c, Smac/Diablo (caspase-dependent), and AIF (caspase-independent) (9-11). We recently demonstrated that minocycline directly targets mitochondria inhibiting PT-dependent release of cytochrome c (3). However, whether release of cytochrome c and additional cell death mitochondrial mediators such as Smac/Diablo or AIF might play a role in HD models or whether minocycline might block their release are currently not known. We therefore evaluated whether minocycline might also inhibit mitochondrial release of mediators of caspase-independent and -dependent cell death pathways in ST14A striatal cells. The shift to a nonpermissive temperature-induced progressive release of AIF, Smac/Diablo, and cytochrome c from the mitochondria in mutant huntingtin-expressing ST14A cells (Fig. 2 a, arrows, and b). As demonstrated by immunofluorescence staining and cell fractionation, minocycline effectively inhibited release of all three cell death mediators (Fig. 2 a and b). Normal cell death function of AIF requires its nuclear translocation after release into the cytoplasm, likely modulating chromatin condensation and DNA fragmentation (14, 20). AIF nuclear translocation is observed after shifting to a nonpermissive temperature by using both immunofluorescence staining and Western blot of fractionated cell lysates (Fig. 2 a, arrowheads, and c). Minocycline inhibited AIF release and nuclear translocation (Fig. 2). Similar results were also confirmed in TNF-α/CHX-mediated parental ST14A striated cells (Fig. 6, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org). These data demonstrate that minocycline inhibits activation of both caspase-independent (AIF) and -dependent (Smac/Diablo and cytochrome c) cell death pathways in vitro.

Fig. 2.

Minocycline inhibits the release of AIF, Smac, and cytochrome c in mutant huntingtin-expressing stable ST14A cells. (a) Mutant huntingtin ST14A cells were shifted at the nonpermissive temperature of 37°C in SDM with or without 10 μM minocycline for 2 h. The cells were fixed and stained with antibodies to AIF, Smac, or cytochrome c. Nuclei were visualized with Hoechst 33342 staining. Arrows indicate the release of AIF, Smac, and cytochrome c. Arrowhead indicates AIF translocation from mitochondria to nuclei by the overlap of AIF and Hoechst 33342 nuclear staining. (Bar = 5 μm.) (b and c) Mutant huntingtin ST14A cells were treated with or without shifting to the nonpermissive temperature for the indicated times. Cytosolic components (b) or nuclear extracts (c) were obtained, and samples (50 μg) were analyzed by Western blot with AIF, Smac, or cytochrome c antibodies. β-Actin was used as a loading control. A single blot, which was stripped, was used for all of the Western blots (b). Histone H2A was used as a nuclear extract loading control (c). The blot is representative of three independent experiments.

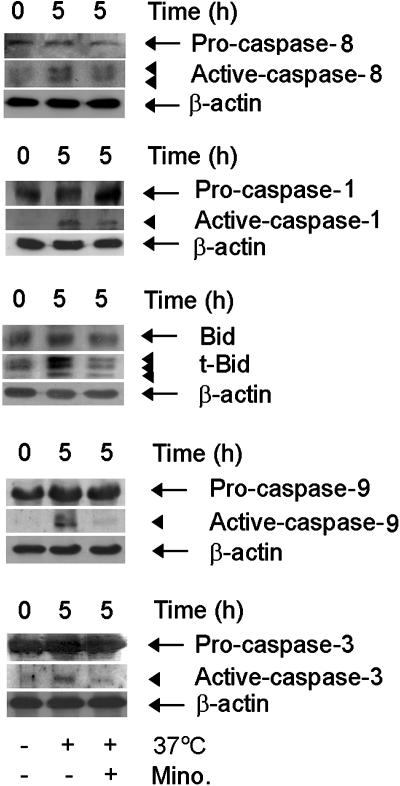

In Vitro Inhibition of Caspase Activation and Bid Cleavage by Minocycline. Caspase activation has been documented to occur as an important modulator of cell death. Given the lack of efficacy of z-VAD.fmk, we evaluated the effect of minocycline on caspase activation. We were most interested in evaluating early caspase activation events and therefore chose to evaluate caspases-9, -8, and -1. We also evaluated the activity of the downstream effector caspase-3. Western blot analysis demonstrated caspases-9, -8 -1, and -3 were activated after shifting to a nonpermissive temperature, and minocycline effectively inhibited their activation (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Minocycline inhibits caspase-8, -1, -9, and -3 activation and Bid cleavage. Mutant huntingtin stable ST14A cells were shifted to the nonpermissive temperature with or without 10 μM minocycline. Cells were extracted for immunoblotting (50 μg per lane) with anticaspase-8, -1, -9, -3 antibodies or anti-Bid antibody. The same blot was reprobed with β-actin antibody and used as a control for equal loading. The blots are representative of three independent experiments.

In addition, we evaluated whether Bid cleavage/activation into the proapoptotic Bcl-2 family member tBid occurred in this cell death paradigm. Associated with cell death, we detected generation of the proapoptotic Bcl-2 family member tBid. Minocycline inhibited tBid generation in this paradigm (Fig. 3). Similar to what was observed in mutant huntingtin-expressing cells, when parental ST14A cells were exposed to TNF-α/CHX, caspase-1, -8, -9, and -3 activation and Bid cleavage were observed by using both semispecific fluorogenic tetrapeptide substrates as well as confirmatory Western blots. Minocycline also effectively inhibited the activation/cleavage of the abovementioned apoptotic factors (Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). These data further verify that caspase activation and Bid cleavage are involved in the mechanism of action of minocycline-mediated neuroprotection.

The evidence presented in Figs. 1, 2, 6, and 7 is consistent with a model where a death stimulus may result in caspase-8 and -1 activation. After caspase activation, caspase-dependent and -independent apoptogenic mitochondrial factors are released into the cytosol. Regulation of release of mitochondrial factors appears to mediate a feedback signal for the final and lethal phase of caspase activation. In the above-described situation, in addition to caspase-dependent pathways, caspase-independent pathways (AIF) mediate the final insult to the cell. Although we have not established in this model that caspase activation results in release of apoptogenic mitochondrial factors, they appear to be temporally related. Minocycline-mediated neuroprotection and inhibition of caspase activation likely occur, at least in part, as a result of inhibiting the mitochondrial amplification feedback loop (21).

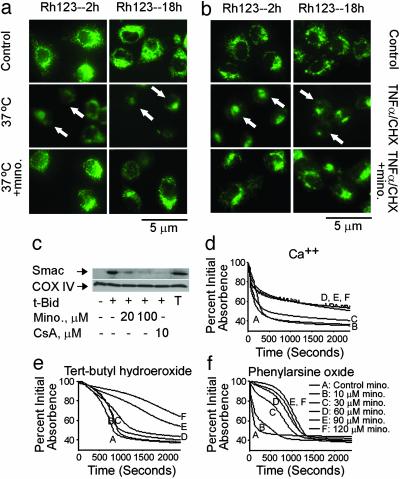

Rescue of Mitochondrial Collapse by Minocycline. Because mitochondria are a key target of minocycline action, we evaluated the mitochondrial events in mutant huntingtin-induced toxicity ST14A cells and in parental ST14A cells exposed to TNF-α/CHX. Specifically, loss of mitochondrial transmembrane potential (Δψm) and alterations in PT induction have been reported as major changes in the commitment 2 pathway in commitment-to-die mitochondrial events (22). We therefore evaluated whether loss of Δψm occurred during ST14A neuronal cell death. In control ST14A cells, rhodamine 123 staining demonstrates a punctate staining consistent with normal mitochondrial Δψm. ST14A cell loss of Δψm was demonstrated as early as 2 h after the shift to a nonpermissive temperature or addition of TNF-α/CHX in mutant huntingtin and parental ST14 cells, respectively. Minocycline inhibited loss of mitochondrial Δψmin both conditions (Fig. 4 a and b).

Fig. 4.

Minocycline inhibits dissipation of Δψm, release of Smac, and induction of PT. (a and b) Mutant huntingtin-expressing ST14 A cells were shifted at the nonpermissive temperature of 37°C in SDM (a), or ST14 A cells were treated with 10 ng/ml TNF-α/10 μM CHX (b) with or without 10 μM minocycline for 2 and 18 h. Cells were stained directly with 2 μM rhodamine 123. Arrows show dissipation of Δψm. (c) Purified mouse brain mitochondria were incubated with minocycline or cyclosporin A. Smac release was induced by tBid and inhibited by addition of minocycline or cyclosporin A. T, total mitochondrial Smac; CsA, cyclosporin A. With the mitochondrial pellets, cytochrome c oxidase subunit IV (COX IV) was used as a loading control. (d-f) Minocycline has distinct mechanisms of action against oxidative and nonoxidative PT inducers. Representative traces from a minimum of three experiments on the effects of minocycline on PT induction. Inducers: 50 μM Ca/Pi (d); 1 mM tert-butyl hydroperoxide 2 μMCa2+ (e); 50 μM phenylarsine oxide (f). PT induction was studied in liver mitochondria isolated from 4- to 6-month-old male Fischer 344 rats. Data for all traces in a single panel were collected at the same time from the same mitochondrial preparation.

To provide additional evidence of the mitochondrial pan-protective properties of minocycline, we evaluated its effect on isolated mitochondria. We demonstrated (3) that minocycline inhibited PT-mediated cytochrome c release in isolated brain and liver mitochondria. We now demonstrate that minocycline, like PT inhibitor cyclosporin A, inhibits calcium- (data not shown) and tBid-mediated Smac/Diablo release from brain mitochondria extracts (Fig. 4c). Consistent with findings from a recent publication, we were unable to readily induce AIF release by tBid from isolated mitochondria, possibly suggesting an alternate mechanism for the release of this apoptogenic factor (23).

TNF-α-mediated cytotoxicity has long been linked to mitochondria and to production of reactive oxygen species (24-26). Although early reports suggesting that TNF-α increased mitochondrial superoxide production have been challenged on technical grounds (27, 28), Liochev and Fridovich (27) noted that TNF-α increases arachidonate production, which can then be converted to alkyl hydroperoxides by lipoxygenase. These alkyl hydroperoxides can react with free iron to form alkoxyl radicals and then attack lipids. These data led to the postulate that Mn-SOD may protect against TNF-α by reducing normal superoxide attack on Fe-S proteins (e.g., aconitase) that would otherwise produce free iron. These observations suggest that TNF-α-associated PT may be more accurately modeled by using an oxidant in addition to calcium, as opposed to the Ca2+ and Bid models used previously (3). We therefore examined minocycline's effect on PT induction by the powerful oxidants tert-butyl hydroperoxide and phenylarsine oxide. In contrast to previous studies on swelling and cytochrome c release after Ca2+/PO4 (e.g., Fig. 4d) or Bid-based challenges, protection by minocycline against oxidant-mediated PT appears functionally distinct. Instead of reducing swelling (as measured by absorbance), minocycline appears to delay induction of PT (Fig. 4 e and f). These effects taken together indicate that minocycline is a multifaceted drug that appears to inhibit mitochondrial recruitment into cell death cascades by at least two mechanisms. One mechanism clearly noted in our previous communication in which both Ca2+/PO4 and Bid were used as inducers, leading to prevention of swelling, even in the face of clearly collapsing Δψm (3). The data presented here appear to be more like those seen with other previously described PT inhibitors in that induction of PT is delayed, but swelling eventually reaches a similar maximum. Minocycline may hit a single target whose effects manifest differently in the different biochemical models used.

Minocycline Inhibits Mitochondrial Caspase-Independent and -Dependent Cell Death Pathways in Vivo. We have demonstrated (29) a functional role of mitochondrial caspase pathways in HD and in R6/2 mice. However, if minocycline directly targets mitochondrial mediators such as AIF, Smac/Diablo, or cytochrome c in the R6/2 HD mouse model is not currently known. R6/2 mice express exon-1 of huntingtin with an expanded polyglutamine repeat under the control of its native promoter (30). R6/2 mice develop a progressive neurological phenotype with some features of HD and have therefore been used as a mouse model of the disease (2, 31). To extend our above in vitro findings in an in vivo model, we investigated whether caspase-independent and -dependent pathways might play a role in R6/2 mice. Furthermore, we evaluated in vivo the effect of minocycline on these pathways. In brains of symptomatic R6/2 mice (saline treated), we find release of AIF, Smac/Diablo, and cytochrome c into the cytosol. AIF, Smac/Diablo, and cytochrome c release is significantly inhibited in minocycline-treated R6/2mice (Fig. 5). This demonstrates Smac/Diablo release in a chronic neurodegenerative disease and of AIF release in a neurologic disease. Furthermore, minocycline is the first drug that can inhibit both caspase-independent (AIF) and -dependent (Smac/Diablo and cytochrome c) mitochondrial cell death pathways in vitro and in vivo.

Mitochondrial cell death mediators, once released into the cytoplasm, have been described to mediate a detrimental amplification loop (21). Consistent with the mitochondrial amplification model, minocycline inhibited caspase-1, -3, and -9 activation as well as Bid cleavage in R6/2 mice (Fig. 5). At the age of mice evaluated (10.5 weeks), we did not detect caspase-8 activation. However, we did detect increased levels of procaspase-8 in R6/2 mouse brain lysates, as compared with wild-type control littermates. Minocycline inhibited procaspase-8 up-regulation, a finding consistent with a noncell autonomous cell death model previously described in chronic neurodegeneration (32).

Discussion

It has recently become increasingly clear that caspase-dependent as well as -independent effector pathways play critical roles in many forms of cell death (2, 3, 12, 14, 30). We demonstrate that Samc/Diablo and AIF are released from the mitochondria in a model of chronic neurodegeneration. Therefore, effective therapeutics requires targeting of caspase-independent as well as -dependent effector pathways. Minocycline inhibits both in vitro and in vivo both caspase-independent and -dependent cell death pathways. Because minocycline is a drug with a proven safety record in humans and possesses blood—brain barrier permeability, minocycline is an attractive candidate for the treatment of disease featuring caspase-independent and -dependent cell death pathways. Furthermore, these data should assist in the development of more effective analogues of minocycline.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank E. Friedlander for editorial assistance. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (to R.M.F., R.J.F., and B.S.K.); the Huntington's Disease Society of America (to R.M.F.); the Hereditary Disease Foundation (to B.S.K.); the Department of Veterans Affairs (to R.J.F.); and a Research Enhancement Award program grant (R.J.F.).

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: AIF, apoptosis-inducing factor; HD, Huntington's disease; CHX, cycloheximide; PT, permeability transition; Δψm, mitochondrial transmembrane potential; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; SDM, serum-deprived medium; 3-NP, 3-nitropropionic acid.

References

- 1.Yrjanheikki, J., Keinanen, R., Pellikka, M., Hokfelt, T. & Koistinaho, J. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 15769-15774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen, M., Ona, V. O., Li, M., Ferrante, R. J., Fink, K. B., Zhu, S., Bian, J., Guo, L., Farrell, L. A., Hersch, S. M., et al. (2000) Nat. Med. 6, 797-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu, S., Stavrovskaya, I. G., Drozda, M., Kim, B. Y., Ona, V., Li, M., Sarang, S., Liu, A. S., Hartley, D. M., Wu, du C., et al. (2002) Nature 417, 74-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanchez Mejia, R. O., Ona, V. O., Li, M. & Friedlander, R. M. (2001). Neurosurgery 48, 1393-1399; discussion, 1399-1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Popovic, N., Schubart, A., Goetz, B. D., Zhang, S. C., Linington, C. & Duncan, I. D. (2002) Ann. Neurol. 51, 215-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu, D. C., Jackson-Lewis, V., Vila, M., Tieu, K., Teismann, P., Vadseth, C., Choi, D. K., Ischiropoulos, H. & Przedborski, S. (2002) J. Neurosci. 22, 1763-1771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tikka, T., Fiebich, B. L., Goldsteins, G., Keinanen, R. & Koistinaho, J. (2001) J. Neurosci. 21, 2580-2588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Green, D. R. & Reed, J. C. (1998) Science 281, 1309-1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li, P., Nijhawan, D., Budihardjo, I., Srinivasula, S. M., Ahmad, M., Alnemri, E. S. & Wang, X. (1997) Cell 91, 479-489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Du, C., Fang, M., Li, Y., Li, L. & Wang, X. (2000) Cell 102, 33-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Susin, S. A., Lorenzo, H. K., Zamzami, N., Marzo, I., Snow, B. E., Brothers, G. M., Mangion, J., Jacotot, E., Costantini, P., Loeffler, M., et al. (1999) Nature 397, 441-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li, L. Y., Luo, X. & Wang, X. (2001) Nature 412, 95-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chai, J. Du, C., Wu, J. W., Kyin, S., Wang, X. & Shi, Y. (2000) Nature 406, 855-862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu, S. W., Yu, S. W., Wang, H., Poitras, M. F., Coombs, C., Bowers, W. J., Federoff, H. J., Poirier, G. G., Dawson, T. M. & Dawson, V. L. (2002) Science 297, 259-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rigamonti, D., Bauer, J. H., De-Fraja, C., Conti, L., Sipione, S., Sciorati, C., Clementi, E., Hackam, A., Hayden, M. R., Li, Y., et al. (2000) J. Neurosci. 20, 3705-3713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang, X., Bauer, J. H., Li, Y., Shao, Z., Zetoune, F. S., Cattaneo, E., Vincenz, C. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 33812-33820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kristal, B. S. & Brown, A. M. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 23169-23175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song, Q., Kuang, Y., Dixit V. M. & Vincenz C. (1999) EMBO J. 18, 167-178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo, R. F., Huber-Lang, M., Wang, X., Sarma, V., Padgaonkar, V. A., Craig, R. A., Riedemann, N. C., McClintock, S. D., Hlaing, T., Shi, M. M., et al. (2000) J. Clin. Invest. 106, 1271-1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daugas, E., Daugas, E., Susin, S. A., Zamzami, N., Ferri, K. F., Irinopoulou, T., Larochette, N., Prevost, M. C., Leber, B., Andrews, D., et al. (2000) FASEB J. 14, 729-739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Slee, E. A., Keogh, S. A. & Martin, S. J. (2000) Cell Death Differ. 7, 556-565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang, L. K., Putcha, G. V., Deshmukh, M. & Johnson, E. M. (2002) Biochimie 84, 223-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arnoult, D., Parone, P., Martinou, J. C., Antonsson, B., Estaquier, J. & Ameisen, J. C. (2002) J. Cell Biol. 159, 923-929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wong, G. H. & Goeddel, D. V. (1988) Science 242, 941-944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wong, G. H., Elwell, J. H., Oberley, L. W. & Goeddel, D. V. (1989) Cell 58, 923-931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schulze-Osthoff, K., Beyaert, R., Vandevoorde, V., Haegeman, G. & Fiers, W. (1993) EMBO J. 12, 3095-3104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liochev, S. I. & Fridovich, I. (1997) Free Radical Biol. Med. 23, 668-671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gardner, P. R. & White, C. W. (1996) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 334, 158-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kiechle, T., Dedeoglu, A., Kubilus, J., Kowall, N. W., Beal, M. F., Friedlander, R. M., Hersch, S. M. & Ferrante, R. J. (2002) Neuromolecular Med. 1, 183-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mangiarini, L., Sathasivam, K., Seller, M., Cozens, B., Harper, A., Hetherington, C., Lawton, M., Trottier, Y., Lehrach, H., Davies, S. W., et al. (1996) Cell 87, 493-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ona, V. O., Li, M., Vonsattel, J. P., Andrews, L. J., Khan, S. Q., Chung, W. M., Frey, A. S., Menon, A. S., Li, X. J., Stieg, P. E., et al. (1999) Nature 399, 263-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li, M., Ona, V. O., Guegan, C., Chen, M., Jackson-Lewis, V., Andrews, L. J., Olszewski, A. J., Stieg, P. E., Lee, J. P., Przedborski, S., et al. (2000) Science 288, 335-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.