Abstract

Objective

To investigate correlates of polypharmacy at discharge from wards of general medicine and geriatrics.

Population

2465 patients enrolled in the Gruppo Italiano di Farmacovigilanza nell’Anziano (GIFA) study.

Main outcome measure

Polypharmacy, ie having more than 6 drugs prescribed at discharge.

Methods

Data on drugs prescribed at home, during hospital stay, and at discharge were collected according to a validated procedure. Logistic regression analysis was used to identify independent correlates of polypharmacy at discharge. The adherence to current therapeutic guidelines was assessed for selected drugs (digitalis, diuretics, antithrombotics, bronchodilators)

Results

The median number of prescribed drugs was 3.0 before admission and 4.0 at discharge (p < 0.001). Polypharmacy prior to admission (Odds Ratio [OR] 4.32, 95% Confidence Interval [CI] 3.13–5.96), cumulative comorbidity (OR 1.81, 95% CI 1.40–2.32) and selected chronicconditions (diabetes, heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, renal insufficiency, and depression) were significant correlates of polypharmacy at discharge. Negative correlate of the outcome was the occurrence of adverse drug reactions prior to admission (OR 0.22, 95% CI 0.09–0.51). The rate of appropriate prescription reached 80% only for antithrombotics either at home or in hospital and at discharge.

Conclusions

Hospitalization increases drug prescription at discharge in elderly patients. Efforts are needed to identify the determinants and to assess the quality of this prescription practice, with the final aim of contrasting polypharmacy.

Keywords: polypharmacy, elderly, epidemiology, comorbidity

Introduction

Elderly people are the greatest consumers of drugs in western countries: the number of daily used drugs rises from 2.0 ± 1.9 for people aged 65–74 years to 2.5 ± 2.0 for people aged 75 and over (Chen et al 2001). Polypathology, a strictly age-correlated phenomenon, is likely to be the main determinant of drug consumption. However, both over-prescribing and improper prescribing has been reported and seems to contribute to the age-related increase in the prevalence of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) (Onder, Pedone, et al 2002; Chang et al 2005). On average, ADRs account for 3%–13% of all the admissions (Atkin and Shenfield 1995; Mannesse et al 2000; Onder, Pedone, et al 2002; Pirmohamed et al 2004) and complicate 5%–20% of the stays of patients over 65 years (Onder, Gambassi, et al 2002; Somers et al 2003; Corsonello et al 2005). Thus, any effort should be made to limit and to rationalize drug prescription. Pursuing such an objective requires that physicians be aware of the dynamics at the basis of polypharmacy in the current clinical practice. In this perspective, it should be clarified whether the hospitalization moderates or promotes drug utilization. Finally, the appropriateness of drug prescription should be also assessed besides quantifying drug use. The present study has been undertaken to assess both correlates of polypharmacy, as estimated on discharge prescriptions from wards of general medicine and geriatrics, and appropriate prescription. A further objective was to investigate the effects of hospitalization on the number of prescribed drugs in the whole population studied and in groups identified by the most prevalent diseases.

Methods

Patients

The present study uses data from a large observational study group, the Gruppo Italiano di Farmacovigilanza nell’Anziano (GIFA), a collaborative group based in community and university hospitals located throughout Italy. GIFA periodically surveyed drug consumption, occurrence of ADRs, and quality of hospital care from 1988 to 1998. We used data on patients consecutively admitted to the 24 participating geriatric or internal medicine wards during the 4-month survey carried out in 1998. We did not use data collected in previous years to minimize the differences in actual prescribing practice. Methods of the GIFA have been previously described (Carosella et al 1999). Briefly, a study physician with specific training completed a questionnaire for each patient at admission to hospital and updated it daily. Data recorded included sociodemographic characteristics, medical variables, complete blood count, neuropsychological and physical function variables.

Overall, 3010 patients were enrolled in the survey period. We excluded patients who died during hospital stay (n = 117) and those with missing data for any of the variables of interest (n = 428, including people with cognitive deficit severe enough to make the completion of geriatric assessment impossible), with a final sample of 2465 patients (839 patients <65 years; 1035 patients 65–79 years; 591 patients 80 years or more). Patients who died during their stay differed from that included in the analysis for a greater prevalence of older age (80 years or more: 57.3% vs 24.0%, p < 0.001), congestive heart failure (CHF) (29.1% vs 16.1%, p < 0.001), and renal failure (15.4% vs 6.9%, p < 0.01). The use of more than 3 drugs prior to admission was similar in both included and excluded patients (63.7% and 63.5%, respectively).

The outcome of the study was having more than 6 drugs prescribed at discharge from the acute care hospital, where 6 corresponds to the 75th percentile of the number of prescribed drugs distribution. Information on pharmacological therapy prior to the hospitalization was collected by asking patients or their relatives to provide all drug samples and their respective prescriptions. This procedure was made according to a previously validated method (Carosella et al 1999). Drugs were coded by Anatomical and Therapeutical Classification (ATC) (Pahor et al 1994).

Variables specifically considered in this study were age, gender, and type of ward. The presence of depressive symptoms was ascertained using the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), and patients with a GDS score greater than 5 were considered as depressed (Lesher and Berryhill 1994). Functional and cognitive capabilities were measured by Basic and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (BADL and IADL) scale (Katz et al 1963), and Hodgkinson Abbreviated Mental Test (AMT) (Jitapunkul et al 1991), respectively. Patients having an AMT score of 7 or less were considered cognitively impaired (Rocca et al 1992). Diagnoses were coded according to International Classification of Diseases, Clinical Modification 9th revision (ICD-9 CM) (WHO 1980). Having more than 4 diagnoses was considered as an index of cumulative comorbidity. Furthermore, highly prevalent age-related chronic conditions that may increase the consumption of drugs (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, cerebral vascular disease, peripheral vascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), chronic renal failure, hepatic insufficiency, and malignancies) were also considered as potential correlates. The number of drugs taken in the 30 days before hospital admission was also considered in the analysis, and information on drug therapy in people with cognitive impairment was collected by caregivers.

Finally, the occurrence of ADRs before admission and during hospital stay were also considered as potential correlates of the outcomes. The study researcher evaluated the participants daily and screened for any new event that could possibly be due to an ADR. For every such event, a dedicated section of the study questionnaire was completed, including the description of the ADR, the suspected drug(s), the severity of the ADR ranging from mild to life-threatening, and an algorithm that provided a graded probability of cause-effect relationship between the suspected drug(s) and the ADR (Naranjo et al 1981).

Procedures conformed to guidelines provided by the Catholic University Ethical Committee.

Statistical analysis

We used contingency tables to compare the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients grouped according to whether they had less than 7, or more than 6 drugs prescribed at discharge. We then built multivariable logistic regression model to evaluate the individual association with polypharmacy of the characteristics whose prevalence was different between the two groups. Since the presence of depressive symptoms has been previously reported to increase the number of prescribed drugs (Antonelli Incalzi et al 2005), the analysis was also repeated after excluding anxiolytic and antidepressant drugs from the definition of polypharmacy. In this secondary analysis we excluded also anxiolytics because of the high prevalence of anxious symptoms in elderly depressed patients (Lenze et al 2001).

The effects of hospitalization on the number of prescribed drugs in the whole population studied and in groups identified by the most prevalent mean diseases were also investigated by comparing the number of drugs taken before admission and prescribed at discharge. Wilcoxon’s signed rank test was used in this analysis because data were not normally distributed.

To verify whether inappropriate prescribing could contribute to increase the number of prescribed drugs at discharge, we also investigated the prevalence of selected clinical conditions in patients having digoxin, diuretics, antithrombotics, or inhaled bronchodilators prescribed before admission, during stay or at discharge. The indications we considered in the analysis were heart failure or atrial fibrillation for digoxin; heart failure, hypertension, and renal or hepatic insufficiency for diuretics; atrial fibrillation, congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, peripheral or cerebral vascular disease for antithrombotics; COPD or asthma for inhaled bronchodilators. Finally, to distinguish the impact of drugs presumably prescribed for a brief period to complete a short term course from that of drugs generally prescribed for long-term therapies on polypharmacy at discharge, we assessed the prevalence of prescription of antibiotics or steroids and that of antihypertensive or hypoglycemic agents. All analyses were performed using SPSS V10.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Of the 2465 patients considered in the analysis, 532 (21.6%) had reduced, 517 (21.0%) had unchanged, and 1,416 (57.4%) had increased number of drugs at discharge with respect to the month prior to admission. The number of patients already taking more than 6 drugs before admission was 172 (7.0%). The outcome was present in 489 (19.8%) patients.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients divided according to the number of drugs prescribed at discharge from the acute care hospital are shown in Table 1. Patients having more than 6 drugs prescribed were slightly older and more frequently female than patients having less than 7 drugs prescribed. Having more than 4 diagnoses was more frequent among those taking more drugs, as were the diagnoses of congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, peripheral vascular disease, COPD, and renal insufficiency. Physical dependency and depressive symptoms, but not cognitive impairment, were more prevalent among patients having 7 or more drugs prescribed at discharge. A history of ADRs prior to admission was negatively correlated with a discharge prescription of over 6 drugs, whereas in hospital ADRs qualified as a positive correlate. Finally, the greater the number of drugs taken at home, the greater the number of drugs prescribed at discharge.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients divided according to the number of drugs prescribed at discharge

| Number of drugs at discharge | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| ≤6 (n = 1976) % | >6 (n = 489) % | p | |

| Age | >0.001 | ||

| <65 | 36.3 | 24.7 | |

| 65–79 | 40.6 | 47.6 | |

| ≥80 | 23.1 | 27.6 | |

| Gender (Male) | 57.5 | 52.8 | 0.056 |

| Type of ward | 0.112 | ||

| Geriatric | 65.7 | 69.5 | |

| Medicine | 34.3 | 30.5 | |

| No of diagnoses >4 | 40.5 | 69.9 | <0.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 12.3 | 31.7 | <0.001 |

| Coronary artery disease | 28.0 | 40.1 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 36.9 | 45.6 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 15.2 | 36.6 | <0.001 |

| Cerebral vascular disease | 13.6 | 14.3 | 0.665 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 4.3 | 7.4 | 0.004 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 9.6 | 19.4 | <0.001 |

| Renal insufficiency | 4.9 | 14.9 | <0.001 |

| Hepatic insufficiency | 7.1 | 7.4 | 0.547 |

| Malignancies | 6.5 | 7.2 | 0.617 |

| Dependency in at least 1 BADL | 7.6 | 14.1 | <0.001 |

| Dependency in at least 1 IADL | 33.1 | 52.1 | <0.001 |

| Cognitive impairment | 19.2 | 17.0 | 0.253 |

| Depression | 25.9 | 42.1 | <0.001 |

| ADRs before admission | 3.8 | 1.6 | 0.016 |

| ADRs during stay | 10.0 | 13.7 | 0.017 |

| No of drugs before admission> 3 | 57.4 | 89.4 | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: ADRs, adverse drug reactions; BADL, basic activities of daily living; IADL, instrumental activities of daily living.

Multivariable logistic regression model showed that age per se was not significantly associated with the outcome. Polypharmacy prior to admission, cumulative comorbidity, diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, COPD, and renal insufficiency were significant correlates of the number of prescribed drugs at discharge. Depressive symptoms also were a significant independent correlate of the outcome, while the occurrence of ADRs prior to admission was the only negative correlate (Table 2). Depressive symptoms remained significantly associated with the outcome also after excluding antidepressant and anxiolytic agents from the computation of the number of prescribed drugs (OR = 1.47; 95% CI = 1.18–2.01).

Table 2.

Summary logistic regression model of selected variables to having more than 6 drugs prescribed at discharge

| OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| <65 | 1.0 | |

| 65–79 | 0.97 | 0.73–1.28 |

| ≥80 | 0.87 | 0.63–1.21 |

| Gender (Males) | 0.81 | 0.64–1.02 |

| No of diagnoses>4 | 1.81 | 1.40–2.32 |

| Congestive heart failure | 2.05 | 1.57–2.68 |

| Coronary artery disease | 1.24 | 0.97–1.58 |

| Hypertension | 1.05 | 0.83–1.32 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 2.65 | 2.07–3.41 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1.36 | 0.86–2.14 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 2.09 | 1.53–2.85 |

| Renal insufficiency | 1.88 | 1.29–3.03 |

| Dependency in at least 1 BADL | 1.33 | 0.92–1.93 |

| Dependency in at least 1 IADL | 1.19 | 0.93–1.52 |

| Depressive symptoms | 1.67 | 1.32–2.12 |

| ADRs before admission | 0.22 | 0.09–0.51 |

| ADRs during stay | 1.41 | 0.97–2.08 |

| No of drugs before admission>3 | 4.32 | 3.13–5.96 |

Abbreviations: ADRs, adverse drug reactions; BADL, basic activities of daily living; IADL, instrumental activities of daily living.

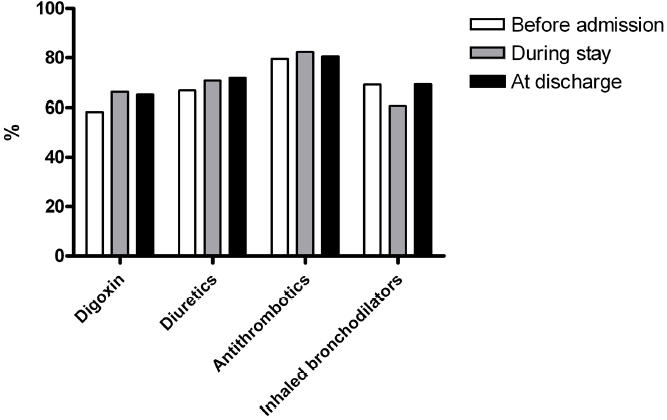

In patients treated with digoxin, the prevalence of recognized indications ranged from 58.4% (at home) to 65.1% (discharge prescription). In patients treated with diuretics, antithrombotics, or inhaled bronchodilators, the corresponding figures were 66.8%, 79.5%, and 69.1% before admission, and 71.9%, 80.5%, and 69.3% at discharge, respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of correct indications in patients having digoxin (atrial fibrillation or congestive heart failure), diuretics (hypertension, congestive heart failure, renal or hepatic insufficiency), antithrombotics (atrial fibrillation, congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, peripheral or cerebral vascular disease, pulmonary embolism or thrombophlebitis) or inhaled bronchodilators (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma or rinhitis) prescribed at home, during hospital stay, and at discharge, respectively.

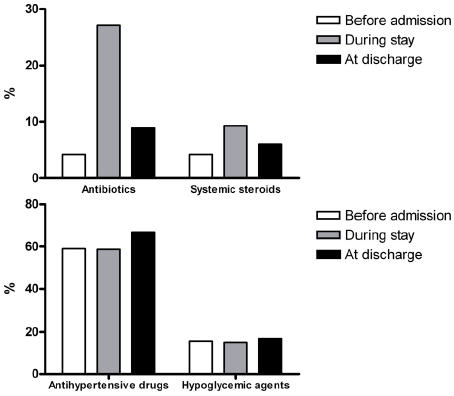

Finally, the use of antibiotics or systemic steroids, ie, drugs which are likely to be prescribed for a brief period to complete a short term course, rose from 4.2% and 4.2% before admission to 8.9% and 6.0% at discharge, respectively. However, the use of drugs prescribed to treat a chronic condition, such as antihypertensives, also increased from 59.0% prior to admission to 66.9% at discharge (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Use of antibiotics or systemic steroids (upper panel), and of antihypertensive or hypoglycemic agents (lower panel), before admission, during hospital stay, and at discharge.

Discussion

The present study shows that age per se does not carry a higher risk of polypharmacy, while age-related polypathology does. Similar results have been previously obtained: comorbid conditions, such as diabetes and chronic lung disease, but not older age, predict a greater complexity and cost of drugs regimen in elderly patients with heart failure (Masoudi et al 2005). Our study also shows that the appropriateness of the prescription is frequently questionable and the hospitalization results in a considerable increase in drug prescription (with regard to previous home therapy). These findings confirm the high prevalence of inappropriate prescribing observed in previous reports from the GIFA study (Onder et al 2003, 2005).

The link between polypathology and polypharmacy is an obvious one, mainly for diseases such as diabetes mellitus or COPD, posing several therapeutic problems which are partly secondary to a variety of complications. However, the lack of a reliable explanation to the use of selected drugs, at least on the basis of current therapeutic guidelines, suggests that over-prescription is a common problem in elderly population. Indeed, there is evidence that diuretics are frequently prescribed to treat edema secondary to venous stasis or chronic respiratory failure (Van Kraij et al 1998; Kelly and Chamber 2000), whereas physical measures and the correction of blood gas derangement should be the respective therapeutic approach (ATS 1995; Kwon et al 2003). Furthermore, both leg edema and COPD have been associated with undue digitalis use (Aronow 1996; Antonelli Incalzi et al 2001). Symptoms such as dyspnea and asthenia, have also been reported to justify the use of digitalis in the absence of a well defined pathogenetic interpretation (Haas and Young 1999). Thus, both over prescription and undue prescription seem to characterize the overall pharmacological therapy of the elderly.

Depressive symptoms are significantly associated with polypharmacy even after having excluded antidepressants and anxiolytics from the computation. This finding replicates results by Simons and colleagues (1992) and Antonelli Incalzi and colleagues (2005), but it is of special concern in an elderly population, which is exposed to a greater risk of ADRs. While the complaint of disparate symptoms likely underlies this association, a lack of attention to the elderly patient might contribute to it. Indeed, general practitioners have been reported to spend 12.4 and 11.2 minutes for visiting an adult (45–64 years old) and an elderly (75 or older) patient, respectively (Radecki et al 1988). Depression is highly prevalent in the elderly (Stek et al 2004), mainly in women, and, thus, physicians should be aware of the problem and spend more time for depressed patients in order to clarify the determinants of depressive symptoms and, thus, reassure the patient and suggest nonpharmacologic measures. For example, insomnia, one of the most common complaints of depressed subjects, frequently resolves with behavioral measures (McCall 2005).

ADRs before admission, but not in hospital ADRs, were negatively correlated with a discharge prescription of over 6 drugs. Although it is possible that ADRs occurring during stay may be due to the addition of new drugs need for the acute condition causing hospitalization, physicians should take into account their personal experience as a guide to the prescription at discharge. Indeed, while selected drugs are plagued by a higher incidence of ADRs, polypharmacy is the main risk factors for ADRs (Hajjar et al 2003). Thus, attempts should be made to curtail inappropriate drug prescription. Unfortunately, such an attempt was made only for patients with a history of ADRs at home.

Surprisingly, internists and geriatricians had a comparable prescription practice. Theoretically, geriatricians should be more aware of problems related to polypharmacy. Present findings are in contrast with such an expectation and are not likely to be confounded by differences in age, comorbidity and functional status between patients admitted to medicine and geriatrics wards. However, the increase in the number of prescribed drugs at discharge could reflect, on average, an increased need in both geriatrics and internal medicine wards.

Limitations for this study deserve consideration. First, using data from 1998, results can not be inferred to the actual prescribing practice. However, the trend towards increased polypharmacy since 1998 have continued on account of evidence based medicine, and potential pitfalls of complex drug regimens in patients with multiple chronic conditions have been recently underlined (Tinetti et al 2004; Boyd et al 2005). New diagnoses made during the stay might justify the increased drug prescription at discharge with regard to previous home therapy. Furthermore, it is possible that patients were not managed properly at home, thus causing their hospital admissions with the resultant addition of drugs to properly manage their diseases. We did not exclude people already taking 6 or more drugs at admission. This choice might have led to an overestimate of the prevalence of polypharmacy at discharge. We decided to leave these patients in our analyses because we could not assume that all of them would have been discharged with 6 or more prescription; furthermore the potential discrepancy is of only about 5%. Finally, some drugs might have been prescribed for a brief period to complete a short-term course. We could not correct our analysis for these potential confounders. However, the fact that most of newly prescribed drugs were devoted to treat chronic conditions suggests that the hospitalization resulted in a true and stable increase in drug use. This conclusion is further strengthened by the evidence that drug prescription at discharge increased for all the main disease categories.

Table 3.

Effects of hospitalization on the number of prescribed drugs in the whole population studied and in the most frequent disease groups

| Number of drugs Median (interquartile range) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before admission | At discharge | Z | p | |

| All patients (n = 2456) | 3.0 (2.0–5.0) | 4.0 (3.0–6.0) | −20.6 | <0.001 |

| CHF (n = 398) | 5.0 (3.0–6.0) | 6.0 (5.0–8.0) | −10.8 | <0.001 |

| NIDDM (N = 480) | 4.0 (2.0–6.0) | 5.5 (4.0–7.0) | −10.4 | <0.001 |

| COPD (N = 285) | 4.0 (2.0–5.0) | 5.0 (4.0–7.0) | −8.8 | <0.001 |

| CRF (N = 169) | 5.0 (3.0–6.5) | 6.0 (4.0–8.0) | −5.9 | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; CRF, chronic renal failure; NIDDM, noninsulin dependent diabetes mellitus.

In conclusion, a trend is evident towards increasing drug prescription to the elderly discharged from general medicine and geriatrics wards. While we cannot clarify the mechanisms underlying this phenomenon, the risks related to polypharmacy in the elderly will never be sufficiently emphasized. Then, interventions should be promoted to identify the determinants and to assess the quality of this prescription practice. Furthermore, the general practitioner, who ultimately decides which therapy her/his patient will follow, should critically evaluate the discharge prescription and, if needed, discuss it with the hospital physician. Finally, while evidence-based guidelines are continuously produced to improve the treatment of more and more diseases, guidelines should also be implemented to provide the operational framework of the approach to the elderly and frail patient.

Acknowledgments

The Gruppo Italiano di Farmacovigilanza nell’Anziano (GIFA) is a research group of the Italian Society of Gerontology and Geriatrics (SIGG)–Fondazione Italiana per la Ricerca sull’Invecchiamento (FIRI-ONLUS). The GIFA is partially supported by a grant from the Italian National Research Council (No 94000402). A complete list of GIFA investigators has been published previously (Corsonello et al 1999).

References

- [ATS] American Thoracic Society. Standards for the diagnosis and care of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;5(Pt 2):S77–S121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonelli Incalzi R, Pedone C, Pahor M, et al. Reasons prompting digitalis therapy in the acute care hospital. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M361–5. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.6.m361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonelli Incalzi R, Corsonello A, Pedone C, et al. Depression and drug utilization in an older population. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2005;1:55–60. doi: 10.2147/tcrm.1.1.55.53603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronow WS. Prevalence of appropriate and inappropriate indications for use of digoxin in older patients at the time of admission to a nursing home. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:588–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb01448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkin PA, Shenfield GM. Medication-related adverse reactions and the elderly: a literature review. Adv Drug React Toxicol Rev. 1995;14:175–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd CM, Darer J, Boult C, et al. Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases: implications for pay for performance. JAMA. 2005;294:716–24. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.6.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carosella L, Pahor M, Pedone C, et al. Pharmacosurveillance in hospitalized patients in Italy. Study design of the ‘Gruppo Italiano di Farmacovigilanza nell’Anziano’ (GIFA) Pharmacol Res. 1999;40:287–95. doi: 10.1006/phrs.1999.0508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CM, Liu PY, Yang YH, et al. Use of the Beers criteria to predict adverse drug reactions among first-visit elderly outpatients. Pharmacotherapy. 2005;25:831–8. doi: 10.1592/phco.2005.25.6.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YF, Dewey ME, Avery AJ. Analysis Group of The Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing (MRCCFA) Study. Self-reported medication use for older people in England and Wales. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2001;26:129–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2710.2001.00333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corsonello A, Pedone C, Corica F, et al. Antihypertensive drug therapy and hypoglycemia in elderly diabetic patients treated with insulin and/or sulfonylureas. Gruppo Italiano di Farmacovigilanza nell’Anziano (GIFA) Eur J Epidemiol. 1999;15:893–901. doi: 10.1023/a:1007645904709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corsonello A, Pedone C, Corica F, et al. Concealed renal insufficiency and adverse drug reactions in elderly hospitalized patients. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:790–5. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.7.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas GJ, Young JB. Inappropriate use of digoxin in the elderly: how widespread is the problem and how can it be solved? Drug Saf. 1999;20:223–30. doi: 10.2165/00002018-199920030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajjar ER, Hanlon JT, Artz MB, et al. Adverse drug reaction risk factors in older outpatients. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2003;1:82–9. doi: 10.1016/s1543-5946(03)90004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jitapunkul S, Pillay I, Ebrahim S. The abbreviated mental test: its use and validity. Age Ageing. 1991;20:332–6. doi: 10.1093/ageing/20.5.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, et al. Studies of illness in aged: the index of ADL, a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963;185:94–106. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly J, Chamber J. Inappropriate use of loop diuretics in elderly patients. Age Ageing. 2000;29:489–93. doi: 10.1093/ageing/29.6.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon OY, Jung DY, Kim Y, et al. Effects of ankle exercise combined with deep breathing on blood flow velocity in the femoral vein. Aust J Physiother. 2003;49:253–8. doi: 10.1016/s0004-9514(14)60141-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenze EJ, Mulsant BH, Shear MK, et al. Comorbidity of depression and anxiety disorders in later life. Depress Anxiety. 2001;14:86–93. doi: 10.1002/da.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesher EL, Berryhill JS. Validation of the Geriatric Depression Scale-Short Form among inpatients. J Clin Psychol. 1994;50:256–60. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199403)50:2<256::aid-jclp2270500218>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannesse CK, Derkx FH, de Ridder MA, et al. Contribution of adverse drug reactions to hospital admission of older patients. Age Ageing. 2000;29:35–9. doi: 10.1093/ageing/29.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masoudi FA, Baillie CA, Wang Y, et al. The complexity and cost of drug regimens of older patients hospitalized with heart failure in the United States, 1998–2001. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:2069–76. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.18.2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCall WW. Diagnosis and management of insomnia in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(7 Suppl):S272–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30:239–45. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1981.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onder G, Pedone C, Landi F, et al. Adverse drug reactions as cause of hospital admissions: results from the Italian Group of Pharmacoepidemiology in the Elderly (GIFA) J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:1962–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onder G, Gambassi G, Scales CJ, et al. Adverse drug reactions and cognitive function among hospitalized older adults. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;58:371–7. doi: 10.1007/s00228-002-0493-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onder G, Landi F, Cesari M, et al. Inappropriate medication use among hospitalized older adults in Italy: results from the Italian Group of Pharmacoepidemiology in the Elderly. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;59:157–62. doi: 10.1007/s00228-003-0600-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onder G, Landi F, Liperoti R, et al. Impact of inappropriate drug use among hospitalized older adults. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;61:453–9. doi: 10.1007/s00228-005-0928-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pahor M, Chrischilles EA, Guralnik JM, et al. Drug data coding and analysis in epidemiologic studies. Eur J Epidemiol. 1994;10:405–11. doi: 10.1007/BF01719664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirmohamed M, James S, Meakin S, et al. Adverse drug reactions as cause of admission to hospital: prospective analysis of 18 820 patients. BMJ. 2004;329:15–19. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7456.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radecki SE, Kane RL, Solomon DH, et al. Do physicians spend less time with older patients? J Am Geriatr Soc. 1988;36:713–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1988.tb07173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocca WA, Bonaiuto S, Lippi A, et al. Validation of the Hodkinson Abbreviated Mental Test as a screening instrument for dementia in an Italian population. Neuroepidemiology. 1992;11:288–295. doi: 10.1159/000110943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons LA, Tett S, Simons J, et al. Multiple medication use in the elderly. Use of prescription and non-prescription drugs in an Australian community setting. Med J Aust. 1992;157:242–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somers A, Petrovic M, Robays H, et al. Reporting adverse drug reactions on a geriatric ward: a pilot project. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;58:707–14. doi: 10.1007/s00228-002-0535-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stek ML, Gussekloo J, Beekman AT, et al. Prevalence, correlates and recognition of depression in the oldest old: the Leiden 85-plus study. J Affect Disord. 2004;78:193–200. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00310-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinetti ME, Bogardus ST, Jr, Agostini JV. Potential pitfalls of disease-specific guidelines for patients with multiple conditions. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2870–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb042458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kraaij DJ, Jansen RW, Gribnau FW, et al. Loop diuretics in patients aged 75 years or older: general practitioners’ assessment of indications and possibilities for withdrawal. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;54:323–7. doi: 10.1007/s002280050467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [WHO] World Health Organization. Clinical modifications. Washington, D.C.: Public Health Service–Health Care Financing Administration; 1980. PHS-HCF. International classification of diseases, 9th revision. [Google Scholar]