Abstract

The human telomeric DNA binding factor TRF1 (hTRF1) and its interacting proteins TIN2, tankyrase 1 and 2, and PINX1 have been implicated in the regulation of telomerase-dependent telomere length maintenance. Here we show that targeted deletion of exon 1 of the mouse gene encoding Trf1 causes early (day 5 to 6 postcoitus) embryonic lethality. The absence of telomerase did not alter the Terf1ex1Δ/ex1Δ lethality, indicating that the phenotype was not due to inappropriate telomere elongation by telomerase. Terf1ex1Δ/ex1Δ blastocysts had a severe growth defect of the inner cell mass that was accompanied by apoptosis. However, no evidence was found for telomere uncapping causing this cell death; chromosome spreads of Terf1ex1Δ/ex1Δ blastocysts did not reveal chromosome end-to-end fusions, and p53 deficiency only briefly delayed Terf1ex1Δ/ex1Δ lethality. These data suggest that murine Trf1 has an essential function that is independent of telomere length regulation.

Telomeres distinguish natural chromosome ends from broken DNA, preventing the activation of a DNA damage response and protecting chromosome ends from end-to-end fusion (reviewed in references 13 and 18). Mammalian telomeres are maintained by telomerase, an RNP enzyme composed of a reverse transcriptase (telomerase reverse transcriptase [TERT]) and a template RNA (telomerase RNA component [TERC]) (reviewed in references 7 and 13). Telomerase synthesizes an array of duplex telomeric repeats which provide binding sites for two closely related telomere binding factors, TRF1 and TRF2 (telomeric repeat binding factors 1 and 2) (6, 11, 15). TRF1 is a small, ubiquitously expressed protein that binds to telomeric DNA as a dimer and recruits additional factors to the telomeric complex (5, 16, 29, 32, 49, 56). Functional studies have implicated human TRF1 (hTRF1) in telomere length homeostasis (52, 55). hTRF1 appears to act as a negative regulator of telomere maintenance, since expression of a dominant-negative allele results in elongation of telomeres, and overexpression of hTRF1 shortens telomeres. Although this resetting of telomere length depends on the expression of telomerase (31), hTRF1 has no effect on telomerase activity per se (52, 55). Therefore, it has been proposed that hTRF1 controls telomere length in cis by affecting the ability of telomerase to extend individual chromosome ends (1, 52, 55). Similarly, the hTRF1-interacting proteins TIN2 (TRF1-interacting protein 2) and tankyrase 1 affect the telomere length setting without changing the activity of telomerase in the cells (32, 48). A fourth hTRF1-interacting factor, PINX1 (protein interacting with NIMA-interacting factor 1), is also a negative regulator of telomere length but has been proposed to act through a different mechanism, involving direct inhibition of telomerase (56).

Although a dominant-negative allele of hTRF1 does not affect the growth and viability of a variety of primary and transformed human cells (30, 31, 52, 55), several observations suggest that hTRF1 may have a role separate from telomere length regulation. hTRF1 has been suggested to be important for telomere protection because it can bind the Ku70/80 heterodimer in vitro, and loss of Ku and DNA protein kinase (DNA-PK) function is known to uncap telomeres (3, 17, 20-22, 25, 26, 43). Furthermore, hTRF1 may play a role in the G2/M DNA damage checkpoint. hTRF1 is a target of the ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) kinase, and phosphorylation on Ser219 by ATM appears to contribute to the ability of overexpressed hTRF1 to induce arrest or apoptosis in G2/M in some settings (33, 34). Additional indirect evidence has implicated TRF1 in the regulation of the mitotic spindle. Green fluorescent protein-tagged TRF1 can localize to the mitotic spindle; TRF1 promotes microtubule polymerization in vitro; it can interact with the microtubule regulator EB1; and the TRF1 partner tankyrase 1 binds to centrosomes and NuMA (37, 38, 44, 48). Together with the finding that TRF1 has several non-telomere-interacting partners (39, 40, 41), these diverse observations could indicate that the function of TRF1 is not limited to telomere length regulation. In agreement with this view, the inactivation of the mouse ortholog of hTRF1 (mTrf1), described in this report, resulted in an embryonic growth defect that was independent of telomere length regulation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Terf1 targeting.

The Terf1 locus was isolated from a P1 129SV library (Genome Systems) by using the full-length mouse cDNA as a probe. The clone contained a 4.4-kb EcoRI fragment upstream of exon 1 (712 to 5,090 bp upstream of the ATG) and a 5.4-kb HindIII fragment downstream of this exon (714 to 6,146 bp downstream from the ATG). These fragments were used to construct the targeting vector in pPNT (54) such that the neo gene replaced exon 1 (Fig. 1). The targeting vector was linearized with NotI, and electroporation and germ line transfer were carried out as described elsewhere (19).

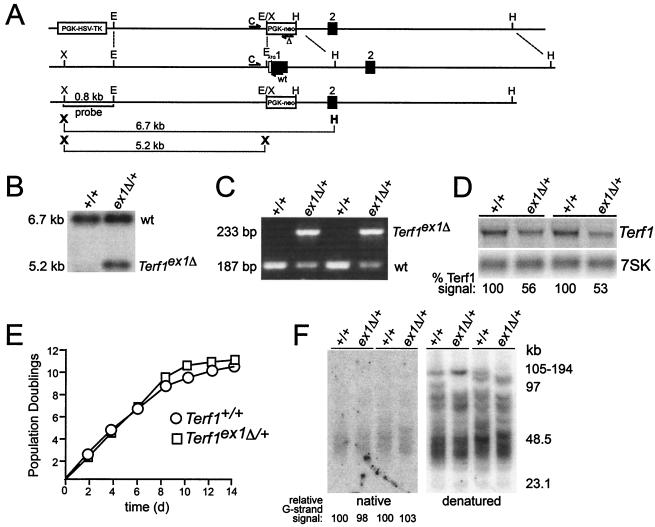

FIG. 1.

Targeted deletion of exon 1 of the mouse Terf1 locus. (A) Schematics of the targeting construct (top line), wild-type locus (second line), and targeted locus (third line) are shown. The bottom line shows the XhoI/HindIII and XhoI fragments used for genotyping. X, XhoI; E, EcoRI; H, HindIII. Positions of PCR primers used for genotyping are indicated by half arrows. Primers are as follows: C, shared by the wild-type and the targeted allele; wt, wild-type allele-specific primer; Δ, primer specific for the targeted allele. (B) Southern blot of XhoI/HindIII-digested DNA from ES cells of the indicated genotypes. The probe is the 0.8-kb XhoI/EcoRI fragment shown in panel A. (C) PCR of wild-type and Terf1ex1Δ/+ ES cells. (D) Northern blot of total RNA from Terf1+/+ and Terf1ex1Δ/+ MEFs. Total RNA was hybridized first with radiolabeled Terf1 cDNA and subsequently with two oligonucleotides complementary to 7SK RNAs. “% Terf1 signal” refers to the signal derived from hybridization with the Terf1 cDNA normalized to loading (7SK signal). (E) Growth curves of Terf1+/+ and Terf1ex1Δ/+ MEFs from E12.5 embryos. (F) Telomeric overhangs and telomeric restriction fragments from Terf1+/+ and Terf1ex1Δ/+ MEFs obtained from littermates from two different litters. Molecular size markers are indicated in kilobase pairs. Relative G-strand overhang intensities were determined by normalization of the native (G-strand) signal to the signal obtained after denaturation (representing duplex TTAGGG repeats). The ratio of G-strand to duplex signals was arbitrarily set to 100 for the DNA in the first lane, and the other ratios were normalized to this value.

DNA isolation and Southern blotting.

For genomic analysis of embryonic stem (ES) D3 cells, DNA was isolated as described elsewhere (31). DNA from tail clips was isolated by lysis of 5-mm-long clips in 500 μl of TNES (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM EDTA, 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate) containing 0.1 mg of proteinase K per ml at 37°C for 5 h. The lysate was extracted with 0.5 ml of phenol-chloroform-isoamyl-alcohol (50:49:1). DNA was collected from the water phase by isopropanol precipitation and centrifugation at 12,000 × g and was dissolved in 50 μl of H2O.

Isolation of MEFs and Northern blotting.

Embryos were removed from the uterus at day 12.5 of gestation, the soft organs were removed with forceps, and mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were prepared as described previously (24). MEFs were cultivated in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium containing 100 U of penicillin per ml, 0.1 mg of streptomycin per ml, 0.2 mM l-glutamine, 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids, and 15% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum (HyClone). Total RNA was isolated from 107 MEFs by using the Clontech Pure Atlas total RNA labeling system as directed by the supplier. RNA was dissolved in 100 μl of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) containing 0.01% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 20 μl was mixed with 15 μl of RNA sample buffer (7.5% formamide, 2% formaldehyde, 0.66% glycerol, and 0.01% bromophenol-blue in 1× MOPS-EDTA [0.02 M morpholinepropanesulfonic acid {MOPS}, 5 mM sodium acetate, 1 mM EDTA {pH 7.0}]), denatured at 65°C for 10 min, size fractionated on an agarose gel (1% agarose-1× MOPS-EDTA-1.2% formaldehyde; running buffer, 1× MOPS-EDTA), and blotted as described previously (45). Membranes were hybridized as described previously (31) with the coding region of Terf1 cDNA (9). Equal gel loading was determined by rehybridization of the membrane with 7SK oligonucleotides at 50°C (10). Signal intensities were determined by using a phosphorimager and ImageQuant software.

PCR genotyping.

Oligonucleotides used for genotyping of Terf1 either were specific for the neomycin resistance gene (Δ, 5′-CTTCCATTTGTCACGTCCTGC-3′) or exon 1 (WT, 5′-GTTAGTCCCAGGACCACATTTG-3′) or were annealed to Terf1 (C, 5′-TTTGAATGAGCACTCTTTGAACC-3′). The amplification reaction was carried out in a volume of 25 μl containing 1 μl of DNA (∼200 ng), 25 pmol of each oligonucleotide, 0.1 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), and 0.5 U of Taq polymerase (AmpliTaq; Perkin-Elmer Cetus). PCR conditions were as follows: 95°C for 1 min; 35 rounds of 95°C for 30 s, 58°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 2 min; and 72°C for 5 min. Oligonucleotides used for genotyping of p53 were p53neo18 (5′-CTATCAGGACATAGCGTTGG-3′), p53ex6F (5′-GTATCCCGAGTATCTGGAAGACAG-3′), and p53ex7RN (5′-AAGGATAGGTCGGCGGTTCATGC-3′). PCR conditions were as follows: 95°C for 1 min; 30 rounds of 95°C for 30 s, 60°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min; and 72°C for 5 min. Oligonucleotides used for genotyping of mTerc were mTR-COM (5′-TTCTGACCACCACCAACTTCAAT-3′), mTR-wt (5′-CTAAGCCGGCACTCCTTACAAG-3′), and mTR-ko (5′-GGGGCTGCTAAAGCGCAT-3′). PCR conditions were as follows: 95°C for 1 min; 30 rounds of 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s; and 72°C for 5 min.

Telomere length and G-strand overhang assays.

A total of 107 MEFs were suspended in 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), mixed with 1 ml of 1% low-melting-point agarose in PBS (50°C), and dispensed into contour-clamped homogeneous electric field (CHEF) sample molds (Bio-Rad). Plugs were incubated in 45 ml of NDS (0.5 M EDTA, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 1% N-laurylsarcosine) containing 0.1 mg of proteinase K per ml at 55°C for 3 days with daily solution changes. Plugs were washed four times in 45 ml of TE (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5]-0.1 mM EDTA) at room temperature, and DNA was digested by incubation in 200 μl of restriction buffer and 50 U each of AluI and MboI. Plugs were loaded into the wells of a 1% agarose gel in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE), and the gel was run for 20 h at 180 V, with a 5-s constant pulse, at 13°C in 0.5× TBE in a CHEF DR2 chamber (Bio-Rad). In-gel telomeric G-strand overhang assays and telomere length analysis were carried out as described previously (31).

In utero slicing and laser capture microscopy.

Histological sections of embryos were prepared as described previously (28). Cellular material was isolated using the Arcturus PixCell laser capture microdissection instrument, and DNA was extracted by lysis in 10 μl of LCM buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA, 1% Tween 20, and 0.04% [wt/vol] proteinase K) at 42°C overnight. A 5-μl volume of the solution was used as a PCR template with two rounds of amplification. T3 and T7 linker sequences were added to the primers for the first round of amplification. Primers were 5′WT (5′-AAT TAA CCC TCA CTA AAG GGA GAA CTC TTT GAA CCC ACG AAG C-3′), 3′WT (5′-TAA TAC GAC TCA CTA TAG GGA GAA GTC CCA GGA CCA CAT TTG A-3′), and 3′ Mut (5′-TAA TAC GAC TCA CTA TAG GGA GAA CGG ATC CAC TAG TAA CGG C-3′). The second round involved amplification of products with primers T3 and T7. PCRs were performed as follows: 95°C for 1 min; 35 rounds of 95°C for 30 s, 58°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 2 min; and 72°C for 5 min.

Dissection of embryos at embryonic day 7.5 (E7.5) to E8.5.

Uteri were dissected, and individual swellings were cut, fixed in Carnoy's solution (60% ethanol, 30% CHCl3, 10% glacial acetic acid) for 1 h, transferred to 70% ethanol, and stained with Mayer's hematoxylin and eosin. Embryos were shelled out and photographed. For genotyping, embryos were lysed in 50 μl of LCM buffer, and 5 μl of the solution was used as a PCR template.

In vitro analysis of blastocysts.

Blastocysts were isolated, cultured, and genotyped as described previously (24, 53). Terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling (TUNEL) assays were performed on day-4 blastocyst cultures growing in 8-well chamber slides by using the ONCOR ApopTag Direct In Situ Apoptosis Detection kit as directed by the supplier, and blastocysts were genotyped as described previously (53). Cells for metaphase spreads were prepared, and metaphase spreads and telomere fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) were carried out as described previously (12, 51). In brief, blastocysts were cultured in 96-well plates for 72 h, treated with 0.1 μg of Colcemid per ml for 6 h, and washed by rinsing with PBS. Trypsinization was carried out with 30 μl of trypsin (0.25%)-EDTA (0.02%) for 5 min at 37°C and terminated with 150 μl of culture medium. Cells were transferred to a 1.5-ml tube, and 60 μl of the suspension was set aside for PCR genotyping. The remaining 120 μl was centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 5 min at room temperature, and the cell pellet was washed in 200 μl of PBS at room temperature, suspended in 500 μl of 0.075 M KCl, and incubated at 37°C for 7 min. The cells were collected by centrifugation at 1,000 × g for 5 min at room temperature, the supernatant was decanted, and the cells were resuspended in the remaining KCl. Five hundred microliters of freshly prepared fixation mix (methanol-acetic acid, 3:1 [vol/vol]) was added dropwise while the tube was tapped to ensure mixing. The cells were fixed at 4°C overnight, collected by centrifugation at 1,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C, resuspended in 25 μl of fresh fixation mix, and dropped onto wet glass slides. Glass slides were processed as described previously (51).

Mouse strains.

Terf1ex1Δ/+ mice were derived from D3 ES cells and backcrossed into the 129SV background for 5 generations prior to phenotypic analysis. mTerc−/− mice and p53 mutant mice were backcrossed into a 129SV/PAS background for 5 generations before being bred to Terf1ex1Δ/+ mice. Accordingly, all littermates used in this study were highly enriched on the 129SV genetic background.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Targeted deletion of Terf1 exon 1 results in embryonic lethality.

Targeted disruption of the mouse Terf1 gene on chromosome 1 (NCBI locus ID 21749) was achieved by deletion of the 298-bp first exon, which encodes the translation initiation site and the first 92 amino acids of mTrf1 (Fig. 1A). This protein segment encompasses the N-terminal acidic domain of mTrf1 (9) and the first helix of the TRF homology (TRFH) domain, a homodimerization domain required for DNA binding activity in vitro (4). To monitor the targeting of the Terf1 locus in ES cells, we made use of the XhoI site in the neomycin resistance gene (neo) (Fig. 1A), which generates a signature 5.2-kb XhoI/HindIII fragment that can be distinguished from the 6.7-kb XhoI/HindIII fragment representing the wild-type allele (Fig. 1B). The genotype of targeted ES cell clones was further confirmed by PCR using a 5′ primer upstream of exon 1, a 3′ primer in exon 1 specific to the wild-type allele, and a 3′ primer in the neo gene specific to the targeted allele (Fig. 1C). This strategy generates a 233-bp product derived from the targeted allele and a 187-bp product derived from the wild-type allele (Fig. 1C). Chimeric mice generated with two independently targeted ES cell clones transmitted the Terf1 disruption to offspring with a Terf1ex1Δ/+ genotype. Consistent with the targeting of the Terf1 locus, Northern blot analysis of the RNA from heterozygous Terf1ex1Δ/+ MEFs showed that cells with a single intact Terf1 allele expressed approximately half the amount of Terf1 mRNA (Fig. 1D). No truncated mRNA species were observed in the heterozygous Terf1ex1Δ/+ MEFs (Fig. 1D and data not shown).

Crosses of Terf1ex1Δ/+ mice failed to yield Terf1ex1Δ/ex1Δ progeny. Genotyping of 917 F1 pups from crosses between Terf1ex1Δ/+ mice revealed no Terf1ex1Δ/ex1Δ animals (Table 1), indicating that Terf1 is an essential gene in the mouse. In addition, the heterozygous genotype was slightly underrepresented (58 versus 66%) in these crosses, raising the possibility that mTrf1 shows partial haploinsufficiency. Because haploinsufficiency has also been noted for mTert and mTerc (23, 35, 36), we examined the status of Terf1ex1Δ/+ heterozygotes in some detail. Heterozygous animals did not display any obvious phenotypes and were fertile. Furthermore, MEFs from E12.5 Terf1ex1Δ/+ embryos grew normally in vitro (Fig. 1E) and displayed no chromosomal aberrations (data not shown). The telomeres of these cells were of normal length, and controlled analysis of the telomere termini suggested that they contained G-strand overhangs (Fig. 1F) that are sensitive to exonuclease I digestion (31) (data not shown). Similar results were obtained with splenocytes derived from adult mice (data not shown). These data suggest that telomere length is not strongly affected by the loss of one allele; however, we cannot exclude subtle changes that are not detectable due to the limitations of our assay. Analysis of Terf1ex1Δ/ex1Δ cells will be necessary to address the effects of the deletion of Terf1 on telomere length.

TABLE 1.

Genotypic ratios of pups from Terf1 heterozygous intercrosses

| Intercross | No. of viable pups | No. (%) with the following genotype:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Terf1+/+ | Terf1ex1Δ/+ | Terf1ex1Δ/ex1Δ | ||

| Terf1ex1Δ/+ × Terf1ex1Δ/+ | 917 | 386 (42) | 531 (58) | 0 (0) |

| Terf1ex1Δ/+p53−/− × Terf1ex1Δ/+p53−/− | 182 | 81 (45) | 101 (55) | 0 (0) |

| Terf1ex1Δ/+Terc−/− × Terf1ex1Δ/+Terc−/− | 167 | 69 (41) | 98 (59) | 0 (0) |

Terf1ex1Δ/ex1Δ embryos die in utero before E6.5 with modest attenuation in a p53−/− setting.

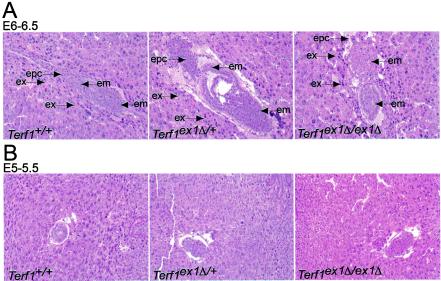

To determine the timing of embryonic death, litters from heterozygous intercrosses were examined by PCR at various times during gestation. Homozygous Terf1ex1Δ/ex1Δ embryos were absent at E7.5 or later (data not shown). Earlier stages of development were studied in utero, with material for PCR genotyping collected by laser capture microdissection. Analysis of four litters containing a total of 32 embryos revealed 10 wild-type, 20 Terf1ex1Δ/+, and 2 Terf1ex1Δ/ex1Δ embryos. The number of homozygous Terf1 embryos was significantly lower than expected (eight), indicating that embryonic failure occurs primarily before E6.5. In agreement with this observation, both E6.5 homozygous mutant embryos showed an abnormal ectoplacental cone and aberrant extraembryonic structures (Fig. 2A), and the uteri contained embryos in the process of being resorbed (data not shown). Two E5 to E5.5 litters with a total of 16 embryos included three Terf1ex1Δ/ex1Δ embryos that looked similar to their wild-type and heterozygous littermates (Fig. 2B), suggesting that E5 to E5.5 is the stage after which survival becomes dependent on mTrf1 function. The survival of embryos up to this stage may be due to a maternal store of mTrf1 or a change in the requirement for mTrf1 during development.

FIG. 2.

Morphologies of Terf1+/+, Terf1ex1Δ/+, and Terf1ex1Δ/ex1Δ embryos. (A) Hematoxylin-and-eosin-stained sections of E6 to E6.5 embryos (in utero) derived from intercrosses between Terf1ex1Δ/+ mice. Extraembryonic (ex), embryonic (em), and ectoplacental-cone (epc) regions are indicated. Genotyping was performed by laser capture and PCR. (B) Hematoxylin-and-eosin-stained sections of E5 to E5.5 embryos (in utero) derived from intercrosses between Terf1ex1Δ/+ mice. Note that the homozygous mutant embryos are grossly similar to their heterozygous and wild-type littermates.

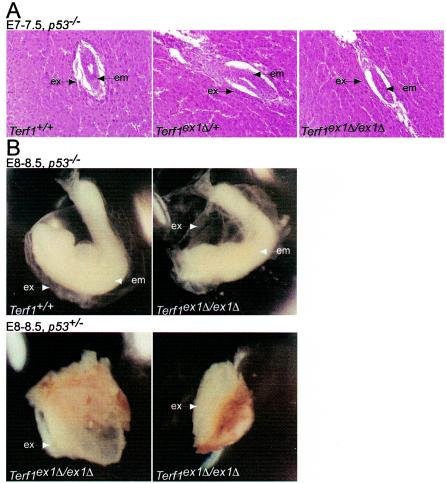

Mouse cells respond to dysfunctional telomeres primarily through the p53 pathway (46, 47). For instance, the phenotype of telomere shortening in Terc−/− mice can be partially suppressed by p53 deficiency, and the growth arrest induced by telomere uncapping is eliminated in p53−/− MEFs (2, 14, 50). To establish whether p53 deficiency can modulate the detrimental effects of Terf1 deficiency, we crossed Terf1ex1Δ/+ mice into a p53−/− background (27), and the offspring of intercrosses between the resulting Terf1ex1Δ/+ p53−/− mice were examined for homozygous deletion of Terf1 exon 1. Among 182 pups resulting from intercrosses of Terf1ex1Δ/+ p53−/− mice, no viable Terf1ex1Δ/ex1Δ pups were found (Table 1). The distribution of wild-type and heterozygous animals in the litters was the same as that in crosses with p53-proficient animals: 45% of the offspring were wild type for Terf1, and 55% were heterozygous for the Terf1ex1Δ allele. To determine whether the timing of embryonic lethality was affected by the absence of p53, Terf1ex1Δ/+ p53−/− and Terf1ex1Δ/+ p53−/+ mice were intercrossed and the embryos were examined at various stages during development. Examination of one litter at E7 to E7.5 containing 7 embryos revealed one intact Terf1ex1Δ/ex1Δ p53−/− embryo, which appeared somewhat smaller than its littermates (Fig. 3A). A second uterus with 10 embryos at E8 to E8.5 contained two Terf1ex1Δ/ex1Δ p53−/− embryos, which were both clearly delayed in development. As in the E6.5 Terf1ex1Δ/ex1Δ embryos, the extraembryonic structures were disorganized in these embryos (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, this litter also contained two Terf1ex1Δ/ex1Δ p53−/+ embryos with abnormalities of the extraembryonic structures. (Fig. 3B). Thus, while p53 deficiency did not fully rescue the Terf1ex1Δ/ex1Δ phenotype, the absence of p53 function did appear to attenuate the timing of the embryonic lethality.

FIG. 3.

p53 deficiency attenuates the embryonic lethality of the Terf1ex1Δ/ex1Δ genotype. (A) Hematoxylin-and-eosin-stained E7 to E7.5 sections of embryos (in utero) from intercrosses between Terf1ex1Δ/+ p53−/− mice. Extraembryonic (ex) and embryonic (em) tissues are indicated. Genotypes were identified by laser capture and PCR. Note that the Terf1ex1Δ/ex1Δ embryo was grossly normal, although smaller than its littermates. (B) E8 to E8.5 embryos derived from intercrosses between Terf1ex1Δ/+ p53−/− mice. Extraembryonic and embryonic regions are indicated.

Embryonic lethality is not rescued by telomerase deficiency.

Since the human ortholog of mTrf1 is a negative regulator of telomerase-mediated telomere elongation, we asked whether the lethality of Terf1ex1Δ/ex1Δ embryos is due to inappropriate telomere lengthening by telomerase. Terf1ex1Δ/+ mice were crossed with telomerase-deficient Terc−/− mice that carry a homozygous deletion of the gene encoding the telomerase template RNA and lack telomerase activity (8). Crosses between Terf1ex1Δ/+ Terc−/− mice failed to generate viable Terf1ex1Δ/ex1Δ pups (Table 1). Of 167 pups born, 69 (41%) were Terf1+/+ and 98 (59%) were Terf1ex1Δ/+ (Table 1). Thus, telomerase deficiency does not rescue the embryonic lethality of Terf1ex1Δ/ex1Δ mice, arguing that this phenotype is not due to inappropriate telomere elongation.

ICM growth defect in ex vivo Terf1ex1Δ/ex1Δ blastocysts.

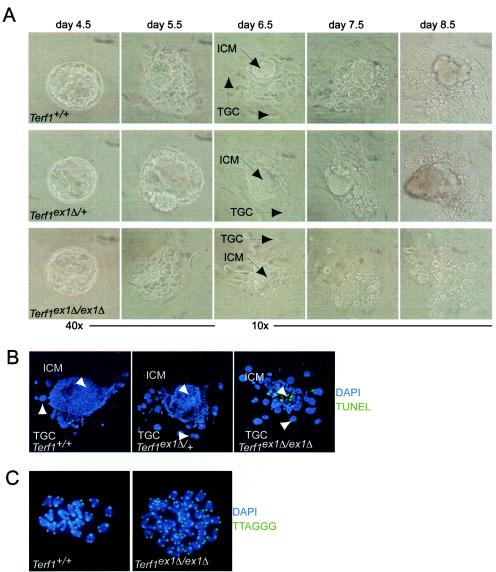

The effect of mTrf1 deficiency on early development was examined by using cultured blastocysts. E3.5 embryos were isolated from Terf1ex1Δ/+ intercrosses, grown in culture for 5 days, and subsequently processed for PCR genotyping. Of 66 blastocysts that were isolated, 11 failed to attach to the substratum and died prior to PCR analysis. Among the 55 attached blastocysts, 18 were Terf1+/+ (27%), 31 were Terf1ex1Δ/+ (47%), and 6 were Terf1ex1Δ/ex1Δ (9%) (Table 2). At the time of isolation and during the first 2 days in culture, the inner cell mass (ICM) of Terf1ex1Δ/ex1Δ blastocysts was indistinguishable from that of Terf1+/+ and Terf1ex1Δ/+ blastocysts. However, while the ICM cells of Terf1+/+ and Terf1ex1Δ/+ embryos continued to expand throughout the 6-day culture period, Terf1ex1Δ/ex1Δ ICM cells failed to grow after day 2 and invariably died by day 5 (Fig. 4A). Only the nondividing trophoblastic giant cells of Terf1ex1Δ/ex1Δ embryos remained after 6 days in culture (Fig. 4A).

TABLE 2.

Blastocysts derived from Terf1ex1Δ/+ intercrosses

| Expt | No. of blastocysts isolated | No. (%) dying before analysis | No. (%) with the following genotypea:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Terf1+/+ | Terf1ex1Δ/+ | Terf1ex1Δ/ex1Δ | |||

| 1 | 66 | 11 (17) | 18 (27) | 31 (47) | 6 (9) |

| 2 | 44 | 6 (14) | 12 (27) | 19 (43) | 7 (16) |

Percentages of TUNEL-positive ICM cells in experiment 2 were 6.3% ± 1.2% for Terf1+/+ blastocysts, 6.8% ± 1.6% for Terf1ex1Δ/+ blastocysts, and 62.1% ± 8.0% for Terf1ex1Δ/ex1Δ blastocysts.

FIG. 4.

Terf1ex1Δ/ex1Δ blastocysts show ICM cell death without detectable telomere fusions. (A) Day-3.5-postcoitus blastocysts isolated from Terf1ex1Δ/+ intercrosses cultured in 96-well plates for 5 days. ICM and trophoblastic giant cells (TGC) are indicated. (B) TUNEL staining of Terf1+/+, Terf1ex1Δ/+, and Terf1ex1Δ/ex1Δ blastocysts. Blastocysts were cultured for 4 days and subjected to TUNEL staining. Green, TUNEL signal; blue, DNA stain (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole [DAPI]). (C) Telomeric FISH on metaphase spreads of Terf1+/+, Terf1ex1Δ/+, and Terf1ex1Δ/ex1Δ blastocysts at day 5.5. Cells were cultured for 2 days, and metaphase spreads were processed for telomeric FISH (green). DNA is stained with DAPI (blue).

The ICM death in Terf1ex1Δ/ex1Δ blastocysts appeared to be due to apoptosis. TUNEL analysis was performed on 38 attached embryos on day 7.5, and the fraction of ICM cells staining positive in the TUNEL assay was determined for each embryo prior to PCR genotyping. The ICM of Terf1+/+ and Terf1ex1Δ/+ blastocysts contained ∼6% TUNEL-positive cells, whereas the fraction of TUNEL-positive ICM cells was ∼10-fold higher (62.1% ± 8%) in Terf1ex1Δ/ex1Δ blastocysts (Table 2; Fig. 4B). These results suggest that mTrf1 is indispensable for ES cell proliferation and that disruption of the Terf1 gene results in a failure of cell proliferation of the ICM. The fact that TUNEL-positive cells are readily detectable in Terf1ex1Δ/ex1Δ embryos indicates that cell death is at least in part due to apoptosis.

Terf1ex1Δ/ex1Δ cells lack telomere fusions.

Considering that mTrf1 is part of the telomeric complex, a possible source of the embryonic lethality and apoptosis in Terf1ex1Δ/ex1Δ embryos is loss of telomere protection (35, 45, 55). Hallmarks of uncapped telomeres are their ability to signal apoptosis (27) and their propensity to fuse with other uncapped telomeres by nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) (51). Mouse ES cells and MEFs with critically shortened telomeres or uncapped telomeres due to Trf2 inhibition show telomere fusions in every metaphase (8, 30, 35, 36, 40). In order to monitor the occurrence of telomere fusions, blastocysts derived from Terf1ex1Δ/+ intercrosses were cultured and processed for chromosome analysis by using telomeric FISH on metaphase spreads. Telomeric DNA was readily detectable at the ends of chromosomes from blastocysts lacking mTrf1 (Fig. 4C), indicating that the telomeric DNA was not subject to extensive degradation. No telomere fusions were observed in 8 (partial) spreads derived from 4 Terf1ex1Δ/ex1Δ blastocysts, representing a total of 304 chromosomes. Chromosome breaks, which are associated with telomere dysfunction (31), were also not observed. These data suggest that Terf1ex1Δ/ex1Δ blastocysts do not suffer from extensive telomere fusions. However, a capping defect could still be responsible for the observed cell death. For instance, Trf1-deficient telomeres may be uncapped but incapable of undergoing NHEJ. Perhaps the removal of the G-strand overhang prior to NHEJ is impaired in this setting or the binding of NHEJ factors (e.g., DNA-PK) is diminished when Trf1 is absent (26). We also note that our analysis could have missed chromosomal aberrations due to Trf1 deficiency, since cells with aberrations might have undergone apoptosis prior to metaphase analysis.

Conclusions.

These data show that deletion of the first exon of Terf1 results in embryonic death prior to or at the time of gastrulation and that this phenotype is not due to unregulated telomerase activity. The lethal phenotype of Terf1 deficiency was unexpected, since inhibition of human TRF1 activity with a dominant-negative allele or RNA interference does not affect the viability of a variety of cell types (30, 31, 52, 55; J. Karlseder, M. van Overbeek, and T. de Lange, unpublished data). Perhaps these knockdown approaches failed to reveal the null phenotype of Terf1, or perhaps mTrf1 has additional functions early in development. In this regard, mTerf1 was recently identified as one of the 230 genes whose expression is specifically associated with the “stem cell phenotype” (42). This finding is remarkable, because neither telomerase nor other components of the telomeric complex belong to this group of genes that determine “stemness.” Further analysis of the putative early function of Trf1 will require an inducible system in which the null phenotype can be studied.

Acknowledgments

We thank Giulia Celli for comments on the manuscript and Devon White for mouse management and genotyping.

J.K. was supported by fellowships from the Human Frontier Science Program and the Charles H. Revson Foundation. H.T. is supported by a fellowship from the Charles H. Revson Foundation. This work was supported by grants from the NIH to T.D.L. (GM49046 and CA76027). T.J. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ancelin, K., M. Brunori, S. Bauwens, C. E. Koering, C. Brun, M. Ricoul, J. P. Pommier, L. Sabatier, and E. Gilson. 2002. Targeting assay to study the cis functions of human telomeric proteins: evidence for inhibition of telomerase by TRF1 and for activation of telomere degradation by TRF2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:3474-3487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Artandi, S. E., S. Chang, S. L. Lee, S. Alson, G. J. Gottlieb, L. Chin, and R. A. DePinho. 2000. Telomere dysfunction promotes non-reciprocal translocations and epithelial cancers in mice. Nature 406:641-645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bailey, S. M., J. Meyne, D. J. Chen, A. Kurimasa, G. C. Li, B. E. Lehnert, and E. H. Goodwin. 1999. DNA double-strand break repair proteins are required to cap the ends of mammalian chromosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:14899-14904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bianchi, A., S. Smith, L. Chong, P. Elias, and T. de Lange. 1997. TRF1 is a dimer and bends telomeric DNA. EMBO J. 16:1785-1794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bianchi, A., R. M. Stansel, L. Fairall, J. D. Griffith, D. Rhodes, and T. de Lange. 1999. TRF1 binds a bipartite telomeric site with extreme spatial flexibility. EMBO J. 18:5735-5744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bilaud, T., C. Brun, K. Ancelin, C. E. Koering, T. Laroche, and E. Gilson. 1997. Telomeric localization of TRF2, a novel human telobox protein. Nat. Genet. 17:236-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blackburn, E. H. 2001. Switching and signaling at the telomere. Cell 106:661-673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blasco, M. A., H. W. Lee, M. P. Hande, E. Samper, P. M. Lansdorp, R. A. DePinho, and C. W. Greider. 1997. Telomere shortening and tumor formation by mouse cells lacking telomerase RNA. Cell 91:25-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Broccoli, D., L. Chong, S. Oelmann, A. A. Fernald, N. Marziliano, B. van Steensel, D. Kipling, M. M. Le Beau, and T. de Lange. 1997. Comparison of the human and mouse genes encoding the telomeric protein, TRF1: chromosomal localization, expression and conserved protein domains. Hum. Mol. Genet. 6:69-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Broccoli, D., L. A. Godley, L. A. Donehower, H. E. Varmus, and T. de Lange. 1996. Telomerase activation in mouse mammary tumors: lack of detectable telomere shortening and evidence for regulation of telomerase RNA with cell proliferation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:3765-3772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Broccoli, D., A. Smogorzewska, L. Chong, and T. de Lange. 1997. Human telomeres contain two distinct Myb-related proteins, TRF1 and TRF2. Nat. Genet. 17:231-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown, E. J., and D. Baltimore. 2000. ATR disruption leads to chromosomal fragmentation and early embryonic lethality. Genes Dev. 14:397-402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan, S. W., and E. H. Blackburn. 2002. New ways not to make ends meet: telomerase, DNA damage proteins and heterochromatin. Oncogene 21:553-563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chin, L., S. E. Artandi, Q. Shen, A. Tam, S. L. Lee, G. J. Gottlieb, C. W. Greider, and R. A. DePinho. 1999. p53 deficiency rescues the adverse effects of telomere loss and cooperates with telomere dysfunction to accelerate carcinogenesis. Cell 97:527-538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chong, L., B. van Steensel, D. Broccoli, H. Erdjument-Bromage, J. Hanish, P. Tempst, and T. de Lange. 1995. A human telomeric protein. Science 270:1663-1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cook, B. D., J. N. Dynek, W. Chang, G. Shostak, and S. Smith. 2002. Role for the related poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases tankyrase 1 and 2 at human telomeres. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:332-342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.d'Adda di Fagagna, F., M. P. Hande, W. M. Tong, D. Roth, P. M. Lansdorp, Z. Q. Wang, and S. P. Jackson. 2001. Effects of DNA nonhomologous end-joining factors on telomere length and chromosomal stability in mammalian cells. Curr. Biol. 11:1192-1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Lange, T. 2002. Protection of mammalian telomeres. Oncogene 21:532-540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Vries, A., E. R. Flores, B. Miranda, H. M. Hsieh, C. T. van Oostrom, J. Sage, and T. Jacks. 2002. Targeted point mutations of p53 lead to dominant-negative inhibition of wild-type p53 function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:2948-2953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Espejel, S., S. Franco, S. Rodriguez-Perales, S. D. Bouffler, J. C. Cigudosa, and M. A. Blasco. 2002. Mammalian Ku86 mediates chromosomal fusions and apoptosis caused by critically short telomeres. EMBO J. 21:2207-2219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gilley, D., H. Tanaka, M. P. Hande, A. Kurimasa, G. C. Li, M. Oshimura, and D. J. Chen. 2001. DNA-PKcs is critical for telomere capping. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:15084-15088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goytisolo, F. A., E. Samper, J. Martin-Caballero, P. Finnon, E. Herrera, J. M. Flores, S. D. Bouffler, and M. A. Blasco. 2000. Short telomeres result in organismal hypersensitivity to ionizing radiation in mammals. J. Exp. Med. 192:1625-1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hathcock, K. S., M. T. Hemann, K. K. Opperman, M. A. Strong, C. W. Greider, and R. J. Hodes. 2002. Haploinsufficiency of mTR results in defects in telomere elongation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:3591-3596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hogan, B., R. Beddington, F. Costantini, and E. Lacey. 1994. Manipulating the mouse embryo: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Plainview, N.Y.

- 25.Hsu, H. L., D. Gilley, E. H. Blackburn, and D. J. Chen. 1999. Ku is associated with the telomere in mammals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:12454-12458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hsu, H. L., D. Gilley, S. A. Galande, M. P. Hande, B. Allen, S. H. Kim, G. C. Li, J. Campisi, T. Kohwi-Shigematsu, and D. J. Chen. 2000. Ku acts in a unique way at the mammalian telomere to prevent end joining. Genes Dev. 14:2807-2812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jacks, T., L. Remington, B. O. Williams, E. M. Schmitt, S. Halachmi, R. T. Bronson, and R. A. Weinberg. 1994. Tumor spectrum analysis in p53-mutant mice. Curr. Biol. 4:1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson, L., K. Mercer, D. Greenbaum, R. T. Bronson, D. Crowley, D. A. Tuveson, and T. Jacks. 2001. Somatic activation of the K-ras oncogene causes early onset lung cancer in mice. Nature 410:1111-1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaminker, P. G., S. H. Kim, R. D. Taylor, Y. Zebarjadian, W. D. Funk, G. B. Morin, P. Yaswen, and J. Campisi. 2001. TANK2, a new TRF1-associated poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase, causes rapid induction of cell death upon overexpression. J. Biol. Chem. 276:35891-35899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karlseder, J., D. Broccoli, Y. Dai, S. Hardy, and T. de Lange. 1999. p53- and ATM-dependent apoptosis induced by telomeres lacking TRF2. Science 283:1321-1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karlseder, J., A. Smogorzewska, and T. de Lange. 2002. Senescence induced by altered telomere state, not telomere loss. Science 295:2446-2449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim, S. H., P. Kaminker, and J. Campisi. 1999. TIN2, a new regulator of telomere length in human cells. Nat. Genet. 23:405-412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kishi, S., and K. P. Lu. 2002. A critical role for Pin2/TRF1 in ATM-dependent regulation. Inhibition of Pin2/TRF1 function complements telomere shortening, radiosensitivity, and the G2/M checkpoint defect of ataxia-telangiectasia cells. J. Biol. Chem. 277:7420-7429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kishi, S., X. Z. Zhou, Y. Ziv, C. Khoo, D. E. Hill, Y. Shiloh, and K. P. Lu. 2001. Telomeric protein Pin2/TRF1 as an important ATM target in response to double strand DNA breaks. J. Biol. Chem. 276:29282-29291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu, Y., H. Kha, M. Ungrin, M. O. Robinson, and L. Harrington. 2002. Preferential maintenance of critically short telomeres in mammalian cells heterozygous for mTert. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:3597-3602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu, Y., B. E. Snow, M. P. Hande, D. Yeung, N. J. Erdmann, A. Wakeham, A. Itie, D. P. Siderovski, P. M. Lansdorp, M. O. Robinson, and L. Harrington. 2000. The telomerase reverse transcriptase is limiting and necessary for telomerase function in vivo. Curr. Biol. 10:1459-1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakamura, M., X. Zhen Zhou, S. Kishi, and K. Ping Lu. 2002. Involvement of the telomeric protein Pin2/TRF1 in the regulation of the mitotic spindle. FEBS Lett. 514:193-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakamura, M., X. Z. Zhou, S. Kishi, I. Kosugi, Y. Tsutsui, and K. P. Lu. 2001. A specific interaction between the telomeric protein Pin2/TRF1 and the mitotic spindle. Curr. Biol. 11:1512-1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Netzer, C., L. Rieger, A. Brero, C. D. Zhang, M. Hinzke, J. Kohlhase, and S. K. Bohlander. 2001. SALL1, the gene mutated in Townes-Brocks syndrome, encodes a transcriptional repressor which interacts with TRF1/PIN2 and localizes to pericentromeric heterochromatin. Hum. Mol. Genet. 10:3017-3024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Niida, H., T. Matsumoto, H. Satoh, M. Shiwa, Y. Tokutake, Y. Furuichi, and Y. Shinkai. 1998. Severe growth defect in mouse cells lacking the telomerase RNA component. Nat. Genet. 19:203-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nosaka, K., M. Kawahara, M. Masuda, Y. Satomi, and H. Nishino. 1998. Association of nucleoside diphosphate kinase nm23-H2 with human telomeres. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 243:342-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ramalho-Santos, M., S. Yoon, Y. Matsuzaki, R. C. Mulligan, and D. A. Melton. 2002. “Stemness”: transcriptional profiling of embryonic and adult stem cells. Science 298:597-600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Samper, E., F. A. Goytisolo, P. Slijepcevic, P. P. van Buul, and M. A. Blasco. 2000. Mammalian Ku86 protein prevents telomeric fusions independently of the length of TTAGGG repeats and the G-strand overhang. EMBO Rep. 1:244-252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sbodio, J. I., H. F. Lodish, and N. W. Chi. 2002. Tankyrase-2 oligomerizes with tankyrase-1 and binds to both TRF1 (telomere-repeat-binding factor 1) and IRAP (insulin-responsive aminopeptidase). Biochem. J. 361:451-459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seiser, C., S. Teixeira, and L. C. Kuhn. 1993. Interleukin-2-dependent transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of transferrin receptor mRNA. J. Biol. Chem. 268:13074-13080. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shay, J. W., O. M. Pereira-Smith, and W. E. Wright. 1991. A role for both RB and p53 in the regulation of human cellular senescence. Exp. Cell Res. 196:33-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shay, J. W., and W. E. Wright. 1989. Quantitation of the frequency of immortalization of normal human diploid fibroblasts by SV40 large T-antigen. Exp. Cell Res. 184:109-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smith, S., and T. de Lange. 2000. Tankyrase promotes telomere elongation in human cells. Curr. Biol. 10:1299-1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smith, S., I. Giriat, A. Schmitt, and T. de Lange. 1998. Tankyrase, a poly-(ADP-ribose) polymerase at human telomeres. Science 282:1484-1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smogorzewska, A., and T. de Lange. 2002. Different telomere damage signaling pathways in human and mouse cells. EMBO J. 21:4338-4348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smogorzewska, A., J. Karlseder, H. Holtgreve-Grez, A. Jauch, and T. de Lange. 2002. DNA ligase IV-dependent NHEJ of deprotected mammalian telomeres in G1 and G2. Curr. Biol. 12:1635-1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smogorzewska, A., B. van Steensel, A. Bianchi, S. Oelmann, M. R. Schaefer, G. Schnapp, and T. de Lange. 2000. Control of human telomere length by TRF1 and TRF2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:1659-1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Takai, H., K. Tominaga, N. Motoyama, Y. A. Minamishima, H. Nagahama, T. Tsukiyama, K. Ikeda, K. Nakayama, and M. Nakanishi. 2000. Aberrant cell cycle checkpoint function and early embryonic death in Chk1−/− mice. Genes Dev. 14:1439-1447. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tybulewicz, V. L., C. E. Crawford, P. K. Jackson, R. T. Bronson, and R. C. Mulligan. 1991. Neonatal lethality and lymphopenia in mice with a homozygous disruption of the c-abl proto-oncogene. Cell 65:1153-1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.van Steensel, B., and T. de Lange. 1997. Control of telomere length by the human telomeric protein TRF1. Nature 385:740-743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhou, X. Z., and K. P. Lu. 2001. The Pin2/TRF1-interacting protein PinX1 is a potent telomerase inhibitor. Cell 107:347-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]