SYNOPSIS

Objectives.

We investigated the effect of race among Hispanic and non-Hispanic people on self-reported diabetes after adjusting for selected individual characteristics and known risk factors.

Methods.

Using the National Health Interview Survey 2000–2003, these analyses were limited to Hispanic and non-Hispanic people who self-identified as white or black/African American for a final sample of 117,825 adults, including 17,327 Hispanic people (with 356 black and 16,971 white respondents).

Results.

The overall prevalence of diabetes was 7.2%. After adjusting for selected covariates, Hispanic white and black respondents were 1.56 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.32, 1.83) and 2.64 (95% CI 1.10, 6.35) times more likely to report having diabetes than non-Hispanic white respondents. The estimate for non-Hispanic black respondents was 1.45 (95% CI 1.29, 1.64). When compared to low-income non-Hispanic white respondents, low-income Hispanic white respondents (odds ratio [OR] 1.64; 95% CI 1.26, 2.19) and non-Hispanic black respondents (OR 1.71; 95% CI 1.38, 2.11) were more likely to report having diabetes. Hispanic black people born in the U.S. were 3.54 (95% CI 1.27, 9.82) times more likely to report having diabetes when compared to Hispanic white people born in the U.S. In comparison to non-Hispanic white respondents, the odds of reporting diabetes decreased for non-Hispanic black respondents, while the odds remained constant for Hispanic white respondents (p-value for interaction between survey year and race/ethnicity = 0.03).

Conclusions.

This study suggests that race may be a proxy for unmeasured exposures among non-Hispanic and Hispanic people. Thus, given the importance of race on health and the racial heterogeneity among Hispanic people, race among Hispanic people should be investigated whenever the data allow it.

In the past two decades, evidence has consistently suggested that Hispanic people have a higher prevalence of diabetes than non-Hispanic white people.1–5 Although the most recent (i.e., 2004) diabetes prevalence estimates among Hispanic people include mostly Mexican Americans, the Hispanic Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (1982–1984) showed that Puerto Rican and Cuban respondents also suffered from an increased burden of diabetes.6 These higher estimates have been attributed to risk factors such as lower socioeconomic status, higher acculturation, and poor access to care among Hispanic people. Even though race also is a strong risk factor for diabetes among non-Hispanic people,4,5,7 this relationship has not been adequately explored among Hispanic people. Because of their mixed ancestry (Europeans, Africans, and Native Americans), Hispanic people can be of any race.8 However, they do not identify well with the U.S. Census categories.9–14

Moreover, although sparse, the evidence on the association between race and health outcomes among Hispanic people is akin with the black/white gap observed among non-Hispanic people: Hispanic black people exhibit worse health outcomes than Hispanic white people.15–18 Thus, it is plausible that Hispanic people's racial identity as black confers negative health exposures, which may be related to the racial hierarchy in U.S. society. Further, similar to non-Hispanic black people,19,20 Hispanic black people may face discrimination based on their skin color not only by non-Hispanic white people but also by their white counterparts.21–24 These seminal studies also stressed the importance of racial heterogeneity among Hispanic people, which, if ignored could mask important patterns of health variations. Therefore, examining race among Hispanic people could provide insight into the role race plays in determining health and disease status.

The National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), an annual survey of U.S. households, affords the opportunity to investigate the effect of race among Hispanic and non-Hispanic respondents on self-reported diabetes after adjusting for selected individual characteristics and known risk factors. Specifically, the purpose of this study was twofold: (1) to investigate the independent effect of race on diabetes among Hispanic and non-Hispanic people and (2) to compare the strength of the associations between race and diabetes among Hispanic and non-Hispanic respondents. Because studies have shown that racial identity and health outcomes among Hispanic people may vary with acculturation,25–27 we tested an interaction term between race and country of birth and length of stay in the U.S.

METHODS

The NHIS is an annual face-to-face interview of a household sample of U.S. noninstitutionalized civilians, using a three-stage stratified cluster probability sampling design. A complete description of the plan and operation for the NHIS has been given elsewhere.28–31

Briefly, the NHIS comprises a core set of questions (repeated yearly) and supplemental questions/modules. The survey oversampled black and Hispanic people to obtain reliable estimates for these groups. The interview sample for NHIS consisted of people aged 0 to 85 years within families within households for a sample of 100,618 people in 2000, 100,760 people in 2001, 93,386 people in 2002, and 92,148 people in 2003. Data for these analyses were extracted from the Person and Sample Adult files and included the records of adults aged 18 years or older, yielding samples of 32,374 in 2000, 33,326 in 2001, 31,044 in 2002, and 30,852 in 2003, for a total of 127,596 people.

The response rates ranged from 87.3% to 88.1% for the Person sample and 72.1% to 74.3% for the Adult sample over the years analyzed. These analyses were limited to Hispanic and non-Hispanic people who self-identified as white or black/African American for a final sample of 117,825 adults, including 17,327 Hispanic people (with 356 black and 16,971 white respondents). Although 42.2% of the Hispanic population identified with the “some other race” category in the 2000 Census,32 this group may have been too heterogeneous and, therefore, was excluded from this analysis.

The outcome for this study was self-reported diabetes (hereafter referred to as diabetes). Information on diabetes was collected using the question, “Have you ever been told by a doctor or health professional that you have diabetes or sugar diabetes?” For women, the phrase “other than pregnant” was added prior to the question to exclude cases of gestational diabetes.

The main independent variable was race/ethnicity. Race was determined from two questions: “What race do you consider yourself to be?” and “Which one of these groups would you say BEST represents yourself?,” where the choices were white, black/African American, Asian, American Indian and Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander, and other. The first question was asked of all survey participants, while the second was asked of those who answered “more than one race” to the first question. These answers were summarized by NHIS as follows: white only, black/African American only, Asian only, American Indian or Pacific Islander only, other race only, or multiple detailed race only.

Ethnicity was established from the question: “Do you consider yourself Hispanic/Latino?” The question for ethnicity was asked before the question for race. For these analyses, race/ethnicity was defined as Hispanic black, Hispanic white, non-Hispanic white, and non-Hispanic black by cross-classifying participants who answered “yes” and “no” to the ethnicity question with those who answered “white only” and “black only” to the race question.

Variables considered as risk factors or potential confounders in studies of diabetes7,33,34 as well as other relevant variables were included in these analyses. These variables included: demographic characteristics (age, gender, marital status, survey year, U.S. region of residence, country of birth, and length of stay in the U.S.), access to care and socioeconomic position (health insurance, education, and income), and health-related risk factors (body mass index [BMI], physical activity, and cigarette smoking). Age (continuous), gender (male/female), survey year (2000, 2001, 2002, and 2003), and U.S. region of residence (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West) were included in the analysis as collected during the interview.

Marital status was specified as married, divorced, widowed, and single. Country of birth was coded as U.S.-born and foreign-born. The foreign-born respondents were asked how long they had been in the U.S., with categories ranging from less than a year to 15 years or more. For analysis purposes, a variable combining country of birth and length of stay in the U.S. was created and coded as foreign-born with less than five years in the U.S., foreign-born with five to 10 years in the U.S., foreign-born with more than 10 years in the U.S., and born in the U.S.

Access to care and socioeconomic position indicators included health insurance, education, and income. Health insurance was collected using several questions regarding multiple sources of insurance and recoded as private, public, and noncoverage. Education was collected as a continuous variable from 0 to 21 and categorized as less than high school, high school graduate or equivalent, some college, and college graduate and higher. Income was collected by asking each participant to select his/her total annual income from 12 categories (ranging from $0 to $75,000 and a refusal category) and was categorized as <$20,000, $20,000 to $44,999, and ≥$45,000. Due to the large number of missing values, the multiple imputations income files were used for these analyses.35

Other risk factors for diabetes included in the analyses were BMI, physical activity, and smoking. BMI (kg/m2) was calculated using self-reported weight and height and was categorized as <18.5 kg/m2 (underweight), 18.5 kg/m2 to <25.0 kg/m2 (healthy weight), and ≥25.0 kg/m2 (overweight including obese).36,37 Physical activity was specified as vigorous activities that cause heavy sweating or large increases in breathing or heart rate less than three times a week for at least 10 minutes, four or more times a week for at least 10 minutes, and never. Smoking status was recoded as current, former, or never.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Descriptive statistics for the characteristics of the population and prevalence of diabetes were calculated by race in each ethnic group. To determine significant differences, Chi-square tests (categorical variables) and t-tests (continuous variables) were used. Chi-square tests were used to assess significant differences in the prevalence of diabetes among groups.

Logistic regression was used to estimate the strength of the association between race/ethnicity and diabetes among U.S. adults (non-Hispanic black, Hispanic black, and Hispanic white as compared to non-Hispanic white). Specifically, the following models were fit to estimate: (1) crude odds ratio (OR) (Crude); (2) OR adjusted for age, gender, marital status, U.S. region of residence, and country of birth/length of stay in the U.S. (Model 1); (3) OR additionally adjusted for health insurance, BMI, physical activity, and smoking (Model 2); and (4) OR additionally adjusted for education and income (Model 3).

Interaction terms between race and country of birth/length of stay in the U.S. were tested among Hispanics. Although four-year estimates were presented to improve reliability, an interaction term was tested between survey year and race/ethnicity to determine any change in the strength of the association between groups over time. In addition, interactions between race/ethnicity and income and education also were tested.

Data management procedures were carried out with SAS38 and the statistical analyses were conducted using SUDAAN.39 SUDAAN takes into account the complex sampling design yielding unbiased standard error (SE) estimates. In addition, to account for the population size across the years of the NHIS surveys aggregated for these analyses, data from the four survey years were first combined and then a new weight variable was created to represent the mean population size across the four years. (Personal communication, Zakia Coriaty Nelson, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, 2006 May 18.) In the tables, the sample sizes were unweighted. However, estimates for means, proportions, SEs, and ORs with 95% CIs were weighted.

RESULTS

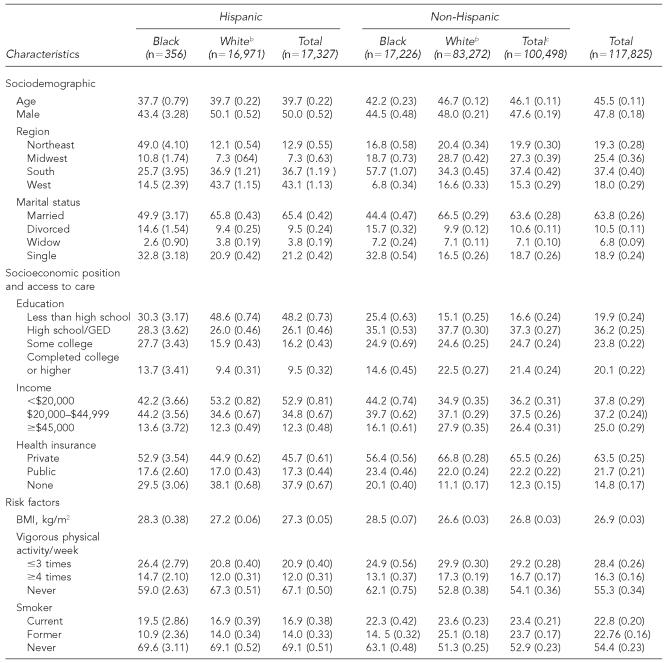

Characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1. Compared to non-Hispanic respondents, Hispanic respondents were more likely to be younger, live in the West, be less educated, have lower income, be uninsured, and were less likely to be physically active and currently smoke. Hispanic people also were more likely to be foreign-born with an average of 10 to 15 years of residence in the U.S. (data not shown). In general, non-Hispanic black respondents had worse sociodemographic and health-related profiles than their white counterparts. For example, non-Hispanic black respondents had lower educational levels, lower income, higher mean BMI, and were more likely to be physically inactive compared to their white counterparts. When compared to Hispanic white people, Hispanic black people were younger and more likely to live in the Northeast, be more educated, have higher income, be physically active, and smoke.

Table 1.

Distribution of selected characteristicsa for Hispanic and non-Hispanic adults ≥18 years of age according to race: National Health Interview Survey, 2000–2003

Percentage (standard errors) with the exception of age (mean and standard error)

All p-values for Chi-square tests and t-tests for comparing black and white respondents within ethnic groups were p<0.01.

All p-values for Hispanic and non-Hispanic comparisons were p<0.01.

GED = general equivalency diploma

BMI = body mass index

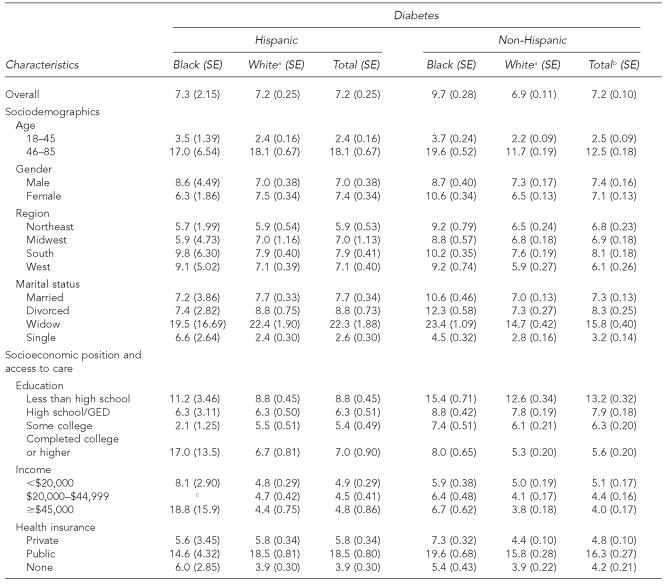

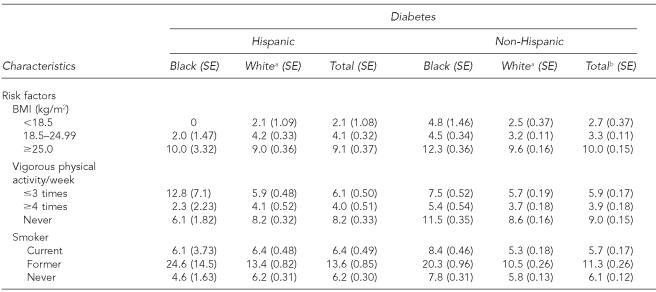

Table 2 shows the prevalence of diabetes for selected covariates for Hispanic and non-Hispanic respondents by race. The overall prevalence of diabetes was 7.2% (SE=0.10; data not shown). In general, when compared to white respondents, black people, regardless of their ethnicity, exhibited the highest prevalence of diabetes across most covariates (most p-values <0.01). However, non-Hispanic black people had a higher prevalence than their Hispanic counterparts. Interestingly, highly educated and high-income Hispanic black respondents exhibited a significantly higher prevalence of diabetes than their lower-educated and low-income white counterparts. In contrast, less-educated non-Hispanic black respondents exhibited a higher prevalence of diabetes than non-Hispanic white respondents. Among Hispanic people, those who were U.S.-born were more likely to report having diabetes than their foreign-born counterparts (8.8% [SE=0.42] vs. 6.3% [SE=0.30], p=0.001; data not shown), with the prevalence of diabetes increasing for those who were foreign-born with time in the U.S. regardless of their race. In fact, the prevalence of diabetes among foreign-born respondents with more than 10 years in the U.S. was similar to the one observed for U.S.-born respondents (8.5%, SE=0.46).

Table 2.

Prevalence of diabetes for selected covariates among Hispanic and non-Hispanic adults ≥18 years of age by race: National Health Interview Survey, 2000–2003

All p-values for Chi-square tests for comparing black and white respondents within ethnic groups were p<0.01, with the exception of gender, region, income among Hispanic people, and gender among non-Hispanic people (p-values for gender and income among Hispanics p>0.05).

All p-values for Hispanic and non-Hispanic comparisons were p<0.01 with the exception of gender.

There was one case of diabetes in this cell. The prevalence estimate was unreliable and therefore not presented.

GED = general equivalency diploma

BMI = body mass index

SE = standard error

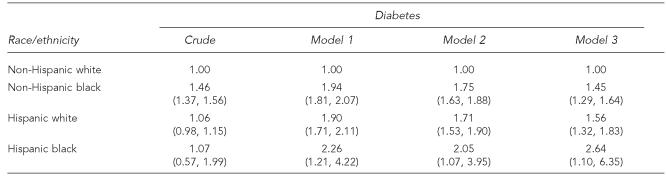

When compared to non-Hispanic white respondents, the unadjusted analysis showed that non-Hispanic black respondents were 1.46 times more likely to report having diabetes (95% CI 1.37, 1.56) (Table 3). After adjustment for selected covariates (Model 3), Hispanic people, regardless of their race, were more likely to report having diabetes than non-Hispanic white people. Specifically, Hispanic white and black respondents were, respectively, 1.56 and 2.64 times more likely to report having diabetes than non-Hispanic white respondents after adjusting for age, gender, marital status, region of residence, length in the U.S., health insurance, physical activity, smoking, BMI, income, and education. The OR for non-Hispanic black respondents was 1.45 (95% CI 1.29, 1.64). There was no difference regarding the effect of race on diabetes among Hispanic and non-Hispanic people (OR=1.76 vs. 1.43, p-value for race and ethnicity = 0.72; data not shown).

Table 3.

Crude and adjusted odds ratios (95% CI)a for diabetes by race/ethnicity among adults ≥18 years of age: National Health Interview Survey, 2000–2003

Crude association between race/ethnicity and self-reported diabetes (crude); odds ratio adjusted for age, gender, marital status, survey year, U.S. region, and country of birth/length in the U.S. (Model 1); additionally adjusted for health insurance, physical activity, smoking, and body mass index (Model 2); and adjusted for all covariates as in Model 2 plus education and income (Model 3).

CI = confidence interval

Among Hispanic people, country of birth seemed to modify the association between race and diabetes (p=0.06; data not shown). When compared to U.S.-born Hispanic white respondents, U.S.-born Hispanic black people were 3.54 times more likely to report having diabetes (95% CI 1.27, 9.82). There was no difference in diabetes reporting between foreign-born Hispanic black and white respondents regardless of length of stay in the U.S.

When compared to non-Hispanic white people, the odds of reporting diabetes has been decreasing for non-Hispanic black respondents (OR=1.86 [2000] vs. OR=1.30 [2003], while the odds have remained constant for Hispanic white respondents (OR=1.54 [2000] vs. OR=1.71 [2003]; p-value for interaction between survey year and race/ethnicity = 0.03; data not shown). Because of the small sample, although an increasing pattern of the odds of reporting diabetes over time was observed, the estimates were unreliable for Hispanic black respondents.

There was no interaction between race/ethnicity and education. However, there was an interaction between income and race/ethnicity (p=0.05; data not shown). When compared to low-income non-Hispanic white people, low-income Hispanic white people (OR=1.64; 95% CI 1.23, 2.19) and non-Hispanic black people (OR=1.71; 95% CI 1.38, 2.11) were more likely to report having diabetes. There was no difference between low-income Hispanic black and non-Hispanic white respondents.

DISCUSSION

This study found that when compared to non-Hispanic white respondents, non-Hispanic black respondents reported having a higher prevalence of diabetes. In the adjusted analyses, the odds of having diabetes were higher for non-Hispanic black, Hispanic black, and white respondents than for non-Hispanic white respondents, with the odds being strongest for Hispanic black people. Low-income non-Hispanic black and Hispanic white people were more likely to report having diabetes than high-income non-Hispanic white people. When compared to non-Hispanic white people, the odds of reporting diabetes have been decreasing for non-Hispanic black people while the odds have remained constant for Hispanic white people. Finally, when compared to Hispanic white respondents born in the U.S., Hispanic black respondents born in the U.S. were more likely to report having diabetes.

Previous studies have consistently reported a higher prevalence of diabetes for Hispanic than for non-Hispanic white respondents and more similar to non-Hispanic black respondents. This finding has been consistent when reporting data on Hispanic people as a whole or for Mexican American people.1,2,4,5 Our study replicated this finding with Hispanic people as a whole or stratified by race exhibiting a higher prevalence of diabetes than non-Hispanic white people. However, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have investigated the association between race and self-reported diabetes among Hispanic people. We found that although the odds of having diabetes were higher for both Hispanic black and white people than for non-Hispanic white people, Hispanic black people exhibited the highest odds of having diabetes.

Evidence suggests that low-income non-Hispanic black and Mexican American respondents exhibited a higher prevalence of diabetes than non-Hispanic white respondents.1,2,7 However, most of these studies have been descriptive in nature. Our study found that the association between race/ethnicity and the prevalence of diabetes applies only to low-income non-Hispanic black and Hispanic white people. Specifically, when compared to low-income non-Hispanic white people, low-income Hispanic white and non-Hispanic black people were more likely to report having diabetes. This finding indicates that income may have a different meaning across racial/ethnic groups.40

Previous studies also have found that acculturation is associated with racial identification with the U.S. Census categories.11,25–27,41–43 Specifically, evidence suggests that length of stay in the U.S., country of birth, and language spoken may influence racial identity by assimilating into the mainstream black/white dichotomy.25,41 For example, among foreign-born Hispanic people, those who have become U.S. citizens were more likely to identify as white than their non-citizen counterparts.25,44 Moreover, acculturation has been found to be associated with diabetes.45,46

We found that the association between race and the prevalence of self-reported diabetes varied with country of birth. Specifically, U.S.-born Hispanic black respondents were more likely to report having diabetes than U.S.-born Hispanic white respondents. However, there was no difference in the prevalence of diabetes between foreign-born Hispanic black and white respondents. Thus, although acculturation to Western culture may lead to a lessening of behaviors and cultural traditions that promote health among Hispanic people, it is also possible that racial assimilation into the U.S. racial categories among Hispanic people channels them to resources and opportunities (or lack thereof) that may influence their health status.

Racial identification with the U.S. Census categories varies among Hispanic subgroups.27 For example, Cubans are more likely to identify as white, Mexicans Americans identify as white or of some other race, and Dominicans and Puerto Ricans exhibited the highest proportion identified as black.27 In these data, similar patterns were replicated, with 92% of Cubans identifying as white, 82% of Mexican Americans identifying as white, and Dominicans (16%) and Puerto Ricans (31%) identifying as black.

To account for this differential racial identification among subgroups and avoid concerns about subgroups instead of racial comparisons, we repeated the analysis for Model 3 among Hispanic people only: There was no difference in the odds of having diabetes among Hispanic subgroups (Puerto Ricans, Dominicans, Cubans, and other Hispanic people as compared to Mexican Americans). Therefore, our findings are robust, which begs the question: What is it about race that may affect diabetes among Hispanic and non-Hispanic people?

Race is a proxy for an array of unmeasured exposures in U.S. society. Specifically, race as a social construct was a concept developed before the contemporary genomics research and did not capture any biologic commonality within groups.20 In contrast, race represents the unequal distribution of power, prestige, and resources according to an individual's racial membership. Moreover, this distribution positions people into the social hierarchy to determine exposures that may promote or deteriorate their health status. The difference in the prevalence of diabetes between non-Hispanic black and white respondents has been attributed to obesity, physical activity, socioeconomic position, access to care, and environmental conditions.34,47 These risk factors also have been found to be associated with diabetes among Hispanic people. Thus, Hispanic black people could be exposed to the same deleterious experiences for diabetes as non-Hispanic black people.

Limitations

Among the strengths of this study were the use of multiple years of a nationally representative sample and the large sample size that allowed the ability to control for numerous potential confounders while also examining interactions. Important limitations were the cross-sectional nature of the data that precluded making inferences regarding cause and effect and the self-reported nature of diabetes. Although self-reported data for this condition have been shown to be highly correlated with physician's records,48 it is possible that our results were underestimated for all racial/ethnic groups. This underestimation could be higher for Hispanic people, as they are less likely to be insured and have less access to care.3,49,50 Moreover, the prevalence reported in this study (7.2%) was higher than the self-reported prevalence of diabetes found in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2002 (6.5%).5 Thus, if the estimates presented here were underestimated, the magnitude of the underestimation may not have been that large.

An additional limitation was the exclusion of 17% of Hispanic people who self-identified as “some other race” (n=3,769). However, we repeated the analyses including “some other race” as a separate category, and their odds of having diabetes was not different from the one observed for Hispanic white people. Therefore, it is very unlikely that their inclusion would have affected the results.

Another limitation was the small sample size of Hispanic black people (n=356) and the possibility of sampling weight inflation. However, we repeated the analyses without the weights as a sensitivity analysis and the results remained the same. Therefore, the possibility of bias, if any, in extrapolating results from a small sample size may be minimal. Finally, the data do not distinguish between type 1 and type 2 diabetes. However, this is not a major concern, as 95% of adults with diabetes are type 2.51

CONCLUSION

This study suggests that race may be a proxy for unmeasured exposures not only among non-Hispanic people but also among Hispanic people. It is obvious that although acculturation to Western culture may lead to a lessening of behaviors and cultural traditions that promote health among Hispanic people, racial assimilation into the U.S. Census racial categories may channel them to resources and opportunities (or lack thereof) that may influence their health status. Thus, given the importance of race on health and the racial heterogeneity among Hispanic people, race among Hispanic people should be investigated whenever the data allow it.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (K22DE15317), the Robert Wood Johnson Health and Society Scholars Program, the Center for the Health of Urban Minority, and the Kellogg Program in Health Disparities.

REFERENCES

- 1.Self-reported prevalence of diabetes among Hispanics—United States, 1994–1997. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999;48(1):8–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prevalence of diabetes among Hispanics—selected areas, 1998–2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53(40):941–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freid VM, Prager K, Mackay AP, Xia H. Hyattsville (MD): National Center for Health Statistics; 2003. Health, United States, 2003, with chartbook on trends in the health of Americans. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harris MI, Flegal KM, Cowie CC, Eberhardt MS, Goldstein DE, Little RR, et al. Prevalence of diabetes, impaired fasting glucose, and impaired glucose tolerance in U.S. adults. The third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:518–24. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.4.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cowie CC, Rust KF, Byrd-Holt DD, Eberhardt MS, Flegal KM, Engelgau MM, et al. Prevalence of diabetes and impaired fasting glucose in adults in the U.S. population: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2002. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1263–8. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flegal KM, Ezzati TM, Harris MI, Haynes SG, Juarez RZ, Knowler WC, et al. Prevalence of diabetes in Mexican Americans, Cubans, and Puerto Ricans from the Hispanic Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1982–1984. Diabetes Care. 1991;14:628–38. doi: 10.2337/diacare.14.7.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cowie CC, Eberhardt MS. National Diabetes Data Group: diabetes in America. 2nd ed. Bethesda (MD): National Institutes of Health; 1995. Sociodemographic characteristics of persons with diabetes; pp. 85–116. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amaro H, Zambrana RE. Criollo, mestizo, mulato, LatiNegro, indigena, white, or black? The US Hispanic/Latino population and multiple responses in the 2000 Census. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:1724–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.11.1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodriguez CE. Race, culture, and Latino “otherness” in the 1980 Census. Social Science Quarterly. 1992;73:930–7. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodriguez CE. Washington: Committee on National Statistics, National Research Council; 1994. Challenges and emerging issues: race and ethnic identity among Latinos. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Falcóon A. Puerto Ricans and the politics of racial identity. In: Harris HW, Blue HC, Griffith EEH, editors. Racial and ethnic identity: psychological development of creative expression. New York: Routledge; 1995. pp. 193–207. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whitten NE, Torres A. Bloomington (IN): Indiana University Press; 1998. Blackness in Latin America and the Caribbean: social dynamics and cultural transformations. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bacal A. Citizenship and national identity in Latin America: the persisting salience of race and ethnicity. In: Oommen TK, editor. Citizenship and national identity: from colonialism to globalism. New Delhi, India: Sage Publications; 1997. pp. 281–312. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martinez-Echázabal L. Mestizaje and the discourse of national/cultural identity in Latin America, 1845–1959. Lat Am Perspect. 1998;25:21–42. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borrell LN. Self-reported hypertension and race among Hispanics in the National Health Interview Survey. Ethn Dis. 2006;16:71–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sorlie PD, Garcia-Palmieri MR, Costas R., Jr. Left ventricular hypertrophy among dark- and light-skinned Puerto Rican men: the Puerto Rico Heart Health Program. Am Heart J. 1988;116:777–83. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(88)90337-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Costas R, Jr., Garcia-Palmieri MR, Sorlie P, Hertzmark E. Coronary heart disease risk factors in men with light and dark skin in Puerto Rico. Am J Public Health. 1981;71:614–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.71.6.614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Landale NS, Oropesa RS. What does skin color have to do with infant health? An analysis of low birth weight among mainland and island Puerto Ricans. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:379–91. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krieger N. Embodying inequality: a review of concepts, measures, and methods for studying health consequences of discrimination. Int J Health Serv. 1999;29:295–352. doi: 10.2190/M11W-VWXE-KQM9-G97Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams DR. Race, socioeconomic status, and health. The added effects of racism and discrimination. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1999;896:173–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Araújo BY, Borrell LN. Understanding the link between discrimination, mental health outcomes, and life chances among Latinos. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2006;28:245–66. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Codina GE, Montalvo FF. Chicano phenotype and depression. Hisp J Behav Sci. 1994;16:296–306. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salgado de Snyder VN. Factors associated with acculturative stress and depressive symptomatology among married Mexican immigrant women. Psychol Women Quarterly. 1987;11:475–88. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stuber J, Galea S, Ahern J, Blaney S, Fuller C. The association between multiple domains of discrimination and self-assessed health: a multilevel analysis of Latinos and blacks in four low-income New York City neighborhoods. Health Serv Res. 2003;38(6 Pt 2):1735–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2003.00200.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tafoya S. Washington: Pew Hispanic Center; 2004. Shades of belonging. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tafoya SM. Latinos and racial identification in California. In: Johnson HP, editor. California counts population trends and profiles. San Francisco: Public Policy Institute of California; 2003. pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saenz R. The American People Census 2000 Population Reference Bureau. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2004. Latinos and the changing face of America. [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Center for Health Statistics. National Health Interview Survey 2000 (machine-readable data file documentation) Hyattsville (MD): National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2002a. Data File Documentation. [Google Scholar]

- 29.National Health Interview Survey 2001 (machine-readable data file documentation) Hyattsville (MD): National Center for Health Statistics; 2002b. Data File Documentation. [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Health Interview Survey 2002 (machine-readable data file documentation) Hyattsville (MD): National Center for Health Statistics; 2003. Data File Documentation. [Google Scholar]

- 31.National Health Interview Survey 2003 (machine-readable data file documentation) Hyattsville (MD): National Center for Health Statistics; 2004. Data File Documentation. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grieco EM, Cassidy RC. Washington: US Census Bureau; 2000. Overview of race and Hispanic origin. [Google Scholar]

- 33.American Diabetes Association. Screening for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(Suppl 1):S11–4. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2007.s11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tull ES, Roseman JM National Diabetes Data Group. Diabetes in America. Bethesda (MD): National Institutes of Health; 1995. Diabetes in African Americans; pp. 613–30. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schenker N, Raghunathan TE, Chiu PL, Makuc DM, Zhang G, Cohen AJ. Multiple imputation of family income and personal earnings in the National Health Interview Survey: methods and examples. 2006. [cited 2007 Jan 16]. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/tecdoc.pdf.

- 36.Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: the evidence report. Obesity Res. 1998;6(Suppl 2):51S–209S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.WHO Consultation on Obesity. WHO Technical Report Series 894. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Geneva; 1997 Jun 3–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.SAS/STAT User's Guide: Version 8.0. Cary (NC): SAS Institute Inc.; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Research Triangle Institute. SUDAAN Language Manual: Release 9.0. Research Triangle Park (NC): Research Triangle Institute; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krieger N, Williams DR, Moss NE. Measuring social class in US public health research: concepts, methodologies, and guidelines. Annu Rev Public Health. 1997;18:341–78. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.18.1.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rodriguez CE. New York: New York University Press; 2000. Changing race. Latinos, the census, and the history of ethnicity in the United States. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hurtado A, Gurin P, Peng T. Social identities—a framework for studying the adaptations of immigrants and ethnics: the adaptation of Mexicans in the United States. Soc Probl. 1994;41:129–51. [Google Scholar]

- 43.De Genova N. Race, space, and the reinvention of Latin America in Mexican Chicago. Lat Am Perspect. 1998;25:87–116. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martin E, DeMaio TJ, Campanelli PC. Context effects for census measures of race and Hispanic origin. Public Opinion Quarterly. 1990;54:551–66. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hazuda HP, Haffner SM, Stern MP, Eifler CW. Effects of acculturation and socioeconomic status on obesity and diabetes in Mexican Americans. The San Antonio Heart Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1988;128:1289–301. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mainous AG, III, Majeed A, Koopman RJ, Baker R, Everett CJ, Tilley BC, et al. Acculturation and diabetes among Hispanics: evidence from the 1999-2002 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Public Health Rep. 2006;121:60–6. doi: 10.1177/003335490612100112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brancati FL, Kao WH, Folsom AR, Watson RL, Szklo M. Incident type 2 diabetes mellitus in African American and white adults: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. JAMA. 2000;283:2253–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.17.2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ngo DL, Marshall LM, Howard RN, Woodward JA, Southwick K, Hedberg K. Agreement between self-reported information and medical claims data on diagnosed diabetes in Oregon's Medicaid population. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2003;9:542–4. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200311000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ramirez R, De la Cruz GP. Washington: US Census Bureau; 2003. The Hispanic population in the United States: March 2002, current population reports, P20-545. [Google Scholar]

- 50.National Center for Health Statistics. Hyattsville (MD): NCHS; 2005. Health, United States, 2005, with chartbook on trends in the health of Americans. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Harris MI. Noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in black and white Americans. Diabetes Metab Rev. 1990;6:71–90. doi: 10.1002/dmr.5610060202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]