Abstract

Background

7B2 is a regulator/activator of the prohormone convertase 2 which is involved in the processing of numerous neuropeptides, including insulin, glucagon and pro-opiomelanocortin. We have previously described a suggestive genetic linkage peak with childhood obesity on chr15q12-q14, where the 7B2 encoding gene, SGNE1 is located. The aim of this study is to analyze associations of SGNE1 genetic variation with obesity and metabolism related quantitative traits.

Methods

We screened SGNE1 for genetic variants in obese children and genotyped 12 frequent single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Case control analyses were performed in 1,229 obese (534 children and 695 adults), 1,535 individuals with type 2 diabetes and 1,363 controls, all French Caucasians. We also studied 4,922 participants from the D.E.S.I.R prospective population-based cohort.

Results

We did not find any association between SGNE1 SNPs and childhood or adult obesity. However, the 5' region SNP -1,701A>G associated with higher area under glucose curve after oral glucose tolerance test (p = 0.0005), higher HOMA-IR (p = 0.005) and lower insulinogenic index (p = 0.0003) in obese children. Similar trends were found in obese adults. SNP -1,701A>G did not associate with risk of T2D but tends to associate with incidence of type 2 diabetes (HR = 0.75 95%CI [0.55–1.01]; p = 0.06) in the prospective cohort.

Conclusion

SGNE1 genetic variation does not contribute to obesity and common forms of T2D but may worsen glucose intolerance and insulin resistance, especially in the background of severe and early onset obesity. Further molecular studies are required to understand the molecular bases involved in this process.

Background

Obesity is a major risk factor for metabolic disorders such as hypertension, dyslipidemia and type 2 diabetes (T2D) [1]. The increased prevalence of metabolic diseases is now affecting young populations as a direct consequence of the increase in childhood obesity [2]. There is evidence for a genetic contribution to the obesity epidemic, especially, for severe forms of obesity, including childhood obesity and severe adult obesity (BMI ≥ 40 Kg/m2) [3].

We previously performed a family based genome-wide scan using microsatellite markers and identified a suggestive obesity susceptibility linkage peak on chromosome 15q12-14 [4]. SGNE1 (Secretory Granule NeuroEndocrine protein 1) coding for 7B2 peptide is located within the 95% confidence interval of this linkage peak [4]. 7B2 mRNA and protein are located in either primarily neuronal (e.g hypothalamus) or endocrine (e.g pancreas and gastrointestinal tract) tissues [5]. 7B2 is a chaperone of the proprotein convertase (PC) 2 [6]. Pro7B2, the 7B2 peptide precursor, regulates the processing of proPC2 and is essential for the activation and regulation of PC2 in secretory granules of neuroendocrine cells [7].

PC2 is an endoprotease involved in the processing of several neuropeptides including proinsulin [8], proglucagon [9], pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) [10] and the cocaine amphetamine regulated transcript (CART) [11]. 7B2 may also affect regulated hormone secretion [12]. Mice studies have shown that invalidation of the genes encoding either PC2 or 7B2 generates major hormone processing deficiency in vivo [13] and is lethal for gene encoding 7B2 in some genetic backgrounds in mice [14]. Interestingly, adrenalectomization of 7B2 knockout mice avoided the lethal phenotype but these animals developed severe obesity [15].

According to this physiological data and the genetic position of SGNE1 under an obesity linkage peak, we hypothesized that SGNE1 is a positional candidate gene for obesity and metabolic disorders in French Caucasians.

Methods

Subjects

Obese

We genotyped 630 obese children (defined as BMI > 97th percentile for age and sex according to a French cohort [16]) selected from 424 nuclear families recruited in Lille through a national media campaign. Genotypes from 105 unrelated obese children recruited in the Children's hospital in Toulouse were also included and, in total, 735 obese children were studied. We selected 534 unrelated obese children for case/control studies. We also genotyped 1219 obese adults (BMI ≥ 30) recruited in Lille or at Hôtel-Dieu hospital in Paris. We selected 695 unrelated severely obese (BMI ≥ 40) and 620 unrelated moderately obese (30 ≤ BMI < 40) adults for case/control analyses. The moderate obese adults are sib pairs of severely obese and parents of obese children.

Type 2 diabetics

We genotyped 360 unrelated type 2 diabetic patients recruited by the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) and Institut Pasteur in Lille and 1175 unrelated type 2 diabetic patients recruited from Endocrinology-Diabetology Department in the Corbeil-Essonne Hospital, Evry.

Controls

Control participants were composed of 623 individuals recruited by CNRS and Institut Pasteur in Lille or through the "Fleurbaix-Laventie Ville Santé" study. Additional 740 control subjects were selected among participants of the Data from the Epidemiology Study on the Insulin Resistance (D.E.S.I.R) study. Control participants were pooled for case control analyses. χ2 tests did not show significant difference in genotype and allele frequencies between both control groups (0.253 ≤ p ≤ 0.886).

Cohort

Participants are from the D.E.S.I.R study, a 9 year follow-up study. We genotyped 4,922 subjects that had data available at baseline (M/F ratio: 49.6/50.4%; age = 47.2 ± 10.0 yrs; BMI = 24.7 ± 3.8 kg/m2). Among them, 4,387 subjects were normoglycemic (fasting plasma glucose<6.1 mmol/l) and 3,370 (77%) were followed for incident impaired fasting glucose (IFG) and T2D. A total of 3,645 participants were non obese (BMI<27 kgm2) at baseline, and 2,829 (78%) could be followed for overweight and obesity. After 9 years of follow-up, 2,053 subjects were both non obese and normoglycemic. T2D was defined as fasting plasma glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/l and/or diabetes treatment.

All adult participants and parents of children signed informed consent. The genetic study was approved by ethical committees at corresponding recruitment centres in Hôtel-Dieu in Paris, C.H.R.U in Lille, Bicêtre Hospital for D.E.S.I.R study, Toulouse Children's Hospital.

Measurements

Weight and height were measured by trained personnel and BMI was calculated as weight/height2 (Kg/m2). During an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), participants received after a 12 h overnight fast 1 g glucose/kg if subject's weight was <50 kg or 75 g glucose if subject's weight was ≥ 50 kg. Blood samples were collected after 0, 30, 60, 90 and 120 min for measurement of plasma glucose using the glucose oxidase procedure and insulin using double-antibody radioimmunoassays. Glucose and insulin related traits were only analyzed in subgroups of 590 obese children and 575 obese adults, all normal glucose tolerant (NGT) (fasting glycemia<6.1 mmol/l). The insulinogenic index was calculated as (Ins30min-Ins0min/Glc30min-Glc0min) and HOMA-IR was calculated as Ins0min/[22.5e-ln(Glc0min)].

Screening for SNPs

SGNE1 has 6 exons and spans 55 kb. We directly sequenced coding regions including exons, exons/introns boundaries, 3 kb upstream ATG codon (including non coding exon1 and intron1) and 1 Kb downstream the stop codon. We used DNA from 48 unrelated obese children and 24 unrelated control adults. PCR amplifications were purified with Montage PCR384 Multiscreen®S384PCR (Millipore). Sequencing was performed using the automated ABI Prism 3730xl DNA sequencer in combination with the Big Dye Terminator cycle (Applied Biosystems) and purification sequencing reaction with MultiScreen®SEQ384 filter plates (Millipore). Data from HapMap phase I was used to select TagSNPs (MAF≥0.05 in CEU population) to improve the genetic coverage of SGNE1.

Genotyping

SNPs identified by direct sequencing were genotyped using either the LightCycler™ or LightTyper™ technologies (Roche). TagSNPs selected from HAPMAP I, and SNP -1,071A>G in the cohort were genotyped by the Applied Biosystems SNPlex™ technology based on the Oligonucleotide Ligation Assay (OLA) combined with multiplex PCR target amplification. Allelic discrimination was performed through capillary electrophoresis analysis using an Applied Biosystems 3730xl DNA Analyzer and GeneMapper3.7 software. All SNPs were re-genotyped in a subset of 379 individuals by direct sequencing to check for genotyping discrepancies. Genotyping error rates were ≤ 0.01 for all SNPs. Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) was tested in controls and was verified for all SNPs (0.11 ≤ p ≤ 0.68).

Statistical analyses

Tests for deviation from HWE and for association were performed by the De Finetti program [17]. Case control analyses for haplotype were performed using THESIAS software [18]. All possible combinations of 1 to 4 SNPs were tested. Haplotypes with a frequency of less than 1% were excluded. Analyses were conducted on inferred and observed genotypes. OGTT glycaemia and insulinemia were analysed by General Linear Model ANOVA for repeated measures. All other quantitative traits (QTs) were analyzed by a univariate ANOVA General Linear Model adjusted for sex, age, BMI, using SPSS 14.0 for windows. Haplotypes associations with QTs were performed using UNPHASED software [19]. Bonferroni correction was applied to quantitative traits as significance threshold (0.05) divided by the number of tests (12 SNPs × 9 QTs = 108) per population. Threshold of significance after adjustment for multiple testing was 0.0005. Survival curves were modelled and analysed by the Kaplan-Meier and Cox tests using R Foundation statistical software (version 2.4.0)

Results

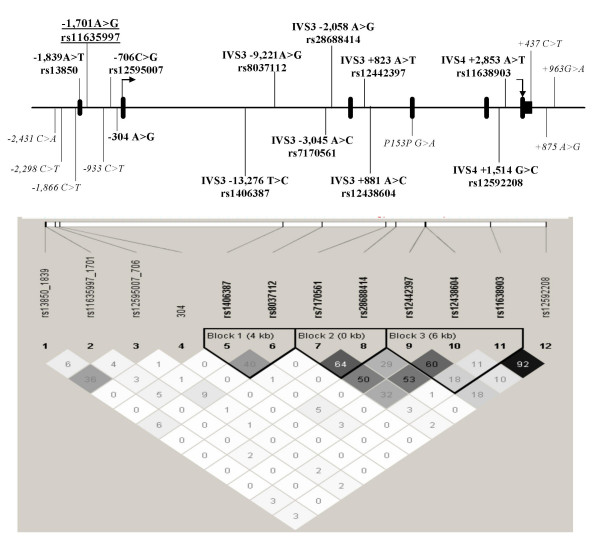

We identified four frequent (minor allele frequency ≥ 5%) and eight rare SNPs by direct sequencing. Frequent SNPs (-1,839A>T, -1,701A>G, -706C>G -304A>G) were all located in the 5' region. In order to improve the genetic coverage of SGNE1, we selected TagSNPs from the HapMap phase I. SNPs with a low genotype call rate (<70%) were not analyzed. Thus, eight TagSNPs all located in introns were added and 12 SNPs (Figure 1) were investigated for association with obesity and related phenotypes.

Figure 1.

SGNE1 genetic variation (A) and LD (B) maps. Genetic variation map: SNPs with MAF ≥ 0.05 are indicated in bold character. SNPs positions were allocated according to the human genome variation society nomenclature http://www.hgvs.org/mutnomen/disc.html#SNP. IVS = intronic variation sequence. rs numbers were indicated for frequent SNPs when available. SNP 1,701A>G is underlined. LD map: LD map was generated using Haploview program. SNPs positions are on scale. LD (measured by correlation coefficient R2) was presented in boxes that correspond to the intersection of two SNPs (e.g. LD between rs13850_1839 and rs11635997_1071 is of 6%).

Clinical characteristics of the populations studied are presented in Table 1. Obesity case control analyses are presented in the Table 2. None of the SGNE1 SNPs or haplotype combination (data not shown) studied showed a significant association with severe forms of obesity in our populations. Thus, as expected, the contribution of these SNPs to linkage with childhood obesity observed on chromosome 15q12-q14 was not significant (data not shown). We also analyzed association of SGNE1 SNPs with moderate obesity (30 ≤ BMI ≤ 40). Case control analyses in additional 620 subjects did not show significant association with this less severe form of obesity (0.06 ≤ p ≤ 0.87; data not shown).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the populations studied.

|

Obese Children N = 735 |

Obese Adults N = 1315 |

T2D N = 1535 |

Control 1 N = 623 |

Control 2 N = 740 |

|

| Age (years) | 11.3 ± 3.2 | 48 ± 13 | 59 ± 11 | 50.9 ± 12 | 53 ± 5.6 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.8 ± 6.2 | 41.5 ± 8.8 | 29.3 ± 5.8 | 22.9 ± 2.3 | 23 ± 1.8 |

| Sex ratio (F/M) | 386/349 | 874/441 | 890/645 | 380/243 | 444/296 |

| Obesity (%) | 100 | 100 | 37 | 0 | 0 |

| Type 2 Diabetes (%) | 1 | 29 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| NGT (%) | 94 | 52 | 0 | 100 | 100 |

| Fasting Glucose (mmol/l) | 4.95 ± 0.5 | 6.66 ± 2.6 | 9.40 ± 3.3 | 5.00 ± 0.4 | 5.05 ± 0.88 |

| Fasting Insulin (pmol/l) | 81.0 ± 58 | 88.2 ± 60 | 66.0 ± 54 | 33.5 ± 25 | 30.5 ± 22 |

Table 2.

Obesity and T2D case control analyses for SGNE1 SNPs. OR: odds ratio. ORs and p values are for allele frequencies comparisons. χ2 test and the p values were computed with De Finetti program [17]. All obese cases are the pooled sample of obese children and severely obese adults.

| Genotype Frequencies | Allele Frequencies | OR [95%CI] (p value) | ||||

| -1839 A>T rs13850 | AA | AT | TT | A | T | |

| Obese Children | 384 | 128 | 21 | 0.84 | 0.16 | 1.10 [0.90–1.34] (0.335) |

| Severely obese adults | 475 | 164 | 20 | 0.85 | 0.15 | 1.06 [0.88–1.28] (0.515) |

| All obese | 859 | 292 | 41 | 0.84 | 0.16 | 1.08 [0.92–1.26] (0.327) |

| Type 2 Diabetes | 777 | 306 | 20 | 0.84 | 0.16 | 1.08 [0.92–1.26] (0.339) |

| Controls | 950 | 335 | 25 | 0.85 | 0.15 | |

| -1,701 A>G rs11635997 | AA | AG | GG | A | G | |

| Obese Children | 191 | 267 | 90 | 0.59 | 0.41 | 1.14 [0.98–1.31] (0.078) |

| Severely obese adults | 266 | 322 | 101 | 0.62 | 0.38 | 1.01 [0.88–1.16] (0.837) |

| All obese | 457 | 589 | 191 | 0.61 | 0.39 | 1.07 [0.95–1.20] (0.255) |

| Type 2 Diabetes | 554 | 722 | 208 | 0.62 | 0.38 | 1.03 [0.92–1.15] (0.619) |

| Controls | 496 | 618 | 178 | 0.62 | 0.38 | |

| -706 C>G rs12595007 | CC | CG | GG | C | G | |

| Obese Children | 384 | 111 | 10 | 0.87 | 0.13 | 0.83 [0.67–1.10] (0.081) |

| Severely obese adults | 439 | 170 | 10 | 0.85 | 0.15 | 1.01 [0.84–1.21] (0.930) |

| All obese | 823 | 281 | 20 | 0.86 | 0.14 | 0.92 [0.79–1.26] (0.343) |

| Type 2 Diabetes | 976 | 352 | 21 | 0.85 | 0.15 | 0.95 [0.82–1.10] (0.511) |

| Controls | 970 | 357 | 28 | 0.85 | 0.15 | |

| -304 A>G | AA | AG | GG | A | G | |

| Obese Children | 445 | 59 | 5 | 0.93 | 0.07 | 1.13 [0.84–1.51] (0.402) |

| Severely obese adults | 587 | 91 | 2 | 0.93 | 0.07 | 1.17 [0.90–1.52] (0.240) |

| All obese | 1032 | 150 | 7 | 0.93 | 0.07 | 1.15 [0.92–1.44] (0.210) |

| Type 2 Diabetes | 1187 | 145 | 3 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.93 [0.74–1.17] (0.555) |

| Controls | 1194 | 151 | 6 | 0.94 | 0.06 | |

| IVS3 -13,276 T>C rs1406387 | TT | TC | CC | T | C | |

| Obese Children | 218 | 239 | 93 | 0.61 | 0.39 | 1.00 [0.86–1.15] (0.996) |

| Severely obese adults | 243 | 340 | 102 | 0.60 | 0.40 | 1.05 [0.91–1.19] (0.510) |

| All obese | 461 | 579 | 195 | 0.61 | 0.39 | 1.02 [0.92–1.14] (0.664) |

| Type 2 Diabetes | 552 | 729 | 251 | 0.60 | 0.40 | 1.06 [0.96–1.18] (0.234) |

| Controls | 499 | 666 | 191 | 0.61 | 0.39 | |

| IVS3-9,221 A>G rs8037112 | AA | AG | GG | A | G | |

| Obese Children | 219 | 233 | 91 | 0.62 | 0.38 | 0.96 [0.83–1.11] (0.606) |

| Severely obese adults | 260 | 322 | 95 | 0.62 | 0.38 | 0.95 [0.82–1.08] (0.422) |

| All obese | 479 | 555 | 186 | 0.62 | 0.38 | 0.97 [0.85–1.07] (0.408) |

| Type 2 Diabetes | 525 | 669 | 209 | 0.61 | 0.39 | 0.98 [0.88–1.10] (0.774) |

| Controls | 481 | 666 | 190 | 0.61 | 0.39 | |

| IVS3 -3,045 A>C rs7170561 | AA | AC | CC | A | C | |

| Obese Children | 248 | 211 | 66 | 0.67 | 0.33 | 1.04 [0.89–1.21] (0.621) |

| Severely obese adults | 318 | 282 | 79 | 0.68 | 0.32 | 1.03 [0.89–1.18] (0.541) |

| All obese | 566 | 493 | 145 | 0.67 | 0.33 | 1.03 [0.92–1.16] (0.598) |

| Type 2 Diabetes | 627 | 603 | 155 | 0.67 | 0.33 | 1.05 [0.94–1.18] (0.372) |

| Controls | 611 | 586 | 129 | 0.68 | 0.32 | |

| IVS3-2,058 A>Grs28688414 | AA | AG | GG | A | G | |

| Obese Children | 307 | 184 | 33 | 0.76 | 0.24 | 1.00 [0.85–1.19] (0.959) |

| Severely obese adults | 394 | 241 | 44 | 0.76 | 0.24 | 1.02 [0.88–1.19] (0.750) |

| All obese | 701 | 425 | 77 | 0.76 | 0.24 | 1.01 [0.89–1.15] (0.809) |

| Type 2 Diabetes | 803 | 480 | 94 | 0.76 | 0.24 | 1.03 [0.91–1.16] (0.678) |

| Controls | 778 | 499 | 71 | 0.76 | 0.24 | |

| IVS3 +823 A>T rs12442397 | AA | AT | TT | A | T | |

| Obese Children | 249 | 215 | 70 | 0.67 | 0.33 | 1.14 [0.98–1.32] (0.094) |

| Severely obese adults | 320 | 293 | 64 | 0.69 | 0.31 | 1.03 [0.89–1.18] (0.670) |

| All obese | 569 | 508 | 134 | 0.68 | 0.32 | 1.08 [0.96–0.1.21] (0.217) |

| Type 2 Diabetes | 720 | 619 | 166 | 0.68 | 0.32 | 1.05 [0.94–1.18] (0.347) |

| Controls | 642 | 583 | 117 | 0.70 | 0.30 | |

| IVS3 +881 A>C rs12438604 | AA | AC | CC | A | C | |

| Obese Children | 323 | 184 | 35 | 0.77 | 0.23 | 1.16 [0.98–1.38] (0.073) |

| Severely obese adults | 416 | 238 | 27 | 0.79 | 0.21 | 1.04 [0.89–1.22] (0.630) |

| All obese | 739 | 422 | 62 | 0.78 | 0.22 | 1.09 [0.96–1.25] (0.181) |

| Type 2 Diabetes | 903 | 463 | 81 | 0.78 | 0.22 | 1.05 [0.92–1.19] (0.459) |

| Controls | 842 | 450 | 55 | 0.79 | 0.21 | |

| IVS4 +2,853 A>T rs11638903 | AA | AT | TT | A | T | |

| Obese Children | 286 | 199 | 61 | 0.71 | 0.29 | 0.98 [0.84–1.15] (0.822) |

| Severely obese adults | 335 | 291 | 56 | 0.70 | 0.30 | 0.99 [0.86–1.14] (0.885) |

| All obese | 621 | 490 | 117 | 0.71 | 0.29 | 0.98 [0.87–1.11] (0.822) |

| Type 2 Diabetes | 703 | 615 | 128 | 0.70 | 0.30 | 1.02 [0.91–1.14] (0.772) |

| Controls | 657 | 588 | 109 | 0.70 | 0.30 | |

| IVS4 +1,514 G>C rs12592208 | GG | GC | CC | G | C | |

| Obese Children | 281 | 195 | 65 | 0.70 | 0.30 | 0.96 [0.82–1.11] (0.591) |

| Severely obese adults | 313 | 289 | 58 | 0.69 | 0.31 | 0.99 [0.85–1.14] (0.873) |

| All obese | 594 | 484 | 123 | 0.70 | 0.30 | 0.97 [0.86–1.10] (0.678) |

| Type 2 Diabetes | 716 | 647 | 139 | 0.69 | 0.31 | 0.99 [0.89–1.11] (0.911) |

| Controls | 616 | 579 | 116 | 0.69 | 0.31 | |

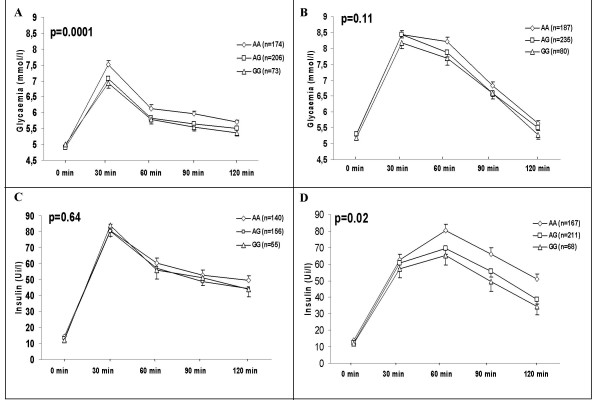

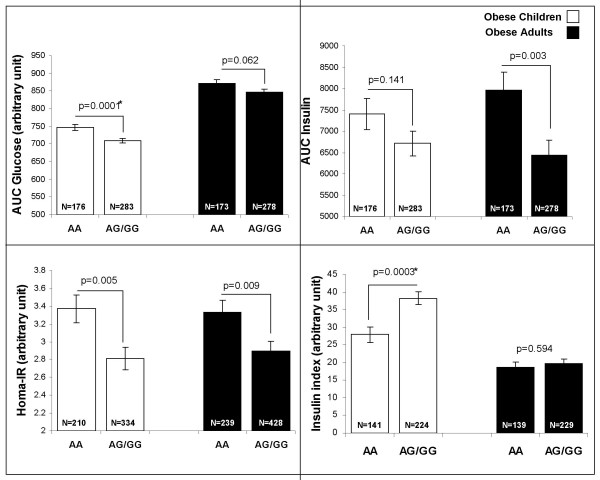

We then investigated associations between SGNE1 SNPs and obesity related quantitative traits in obese subjects. SNP-1,701A>G, located in intron 1 which is part of the 5' region of SGNE1 (Figure 1), showed several strong and consistent associations with glucose intolerance. In obese children, despite no significant difference for fasting glucose, SNP -1,701A>G associated with an average 0.5 mmol/l increase (p = 0.0002) in glucose levels 30 min after an OGTT (Figure 2A) suggesting that -1,701A>G might alter the early insulin response after a glucose load. Indeed, the allele -1,701A carriers showed a 27% decrease in the insulinogenic index, an estimator of insulin secretion capacity (p = 0.0003) (Figure 3). Differences in glucose levels according to -1,701A>G genotypes were still significant after 120 min (p = 0.005). Thus, -1,701A>G associated with a 6% increase in the area under the curve (AUC) for glucose after OGTT (Figure 3; p = 0.0001). On the other hand, excepting for a borderline association with fasting insulin levels (p = 0.034), no significant differences were observed according to the -1,701A>G genotype for insulin levels during the OGTT (Figure 2B). Consequently, SNP -1,701A>G did not associate with AUC for insulin (p = 0.141) (Figure 3). However, the -1,701A allele associated with higher circulating fasting levels of pro-insulin in obese children (p = 0.037, data not shown).

Figure 2.

Plasma glucose (A and B) and plasma insulin (C and D) after OGTTs in obese children (A and C) and obese adults (B and D) according to SNP -1,701A>G (rs11635997) genotypes. Glucose and insulin levels during OGTT were compared using a general linear model ANOVA for repeated measures, adjusted for age, sex, and BMI. P values are for the dominant model (AA vs. AG+GG).

Figure 3.

SNP -1,701A>G associations with insulin and glucose related traits in obese children and obese adults. Quantitative traits were compared using a General Linear Model ANOVA adjusted for age, sex, and BMI for a dominant model (AA vs. AG+GG).*: association is significant after Bonferroni correction (new threshold after correction = 0.0005, see statistical methods for more details).

In obese NGT adults, SNP -1,701A>G was also associated with glucose levels but only after 60 min (p = 0.038) and tended to be associated with higher levels at 90 min (p = 0.06) and 120 min (p = 0.085) (Figure 2C). Accordingly, we only observed a trend for an association between -1,701A>G and the AUC for glucose (p = 0.06) in obese adults (Figure 3). In addition to association with higher fasting insulin levels (p = 0.028), which was also seen in children, SNP -1,701A>G was associated with higher insulin levels after 60 min (p = 0.013), 90 min (p = 0.012) and 120 min (p = 0.001) (Figure 2D). Thus, SNP -1,701A>G associated with a higher AUC for insulin (p = 0.003) (Figure 3). SNP -1071A>G also associated with a higher insulin resistance index HOMA-IR in obese children (p = 0.005) and adults (p = 0.009) (Figure 3). The associations with AUC glucose and insulinogenic index continue reaching significance after Bonferroni correction in obese children only (for more details, see methods/statistical analyses). No haplotype combination showed stronger or independent association from -1,701A>G with glucose levels, insulinogenic index and HOMA-IR in obese children and obese adults (data not shown).

We then investigated the role of SNP -1,701A>G in the risk of T2D. We genotyped SGNE1 SNPs, including -1,701A>G in an independent population of 1,535 type 2 diabetics. SGNE1 SNPs or halpotypes (data not shown) did not associate with T2D (Table 2) in the whole population or in groups stratified for obesity or age of T2D onset before 45 y (data not shown). Logistic regression using age and sex as covariates did not show any significant association between T2D and SNP -1,701A>G either. Interestingly, SNP -1,701A>G was associated with a higher BMI in type 2 diabetic patients (mean AA = 33.6 ± 0.4 kg/m2 vs AG/GG = 32.5 ± 0.3 kg/m2; p = 0.022, data not shown) but not HbA1C levels (mean AA = 8.26 ± 0.1 vs. AG/GG 8.42 ± 0.1; p = 0.29, data not shown).

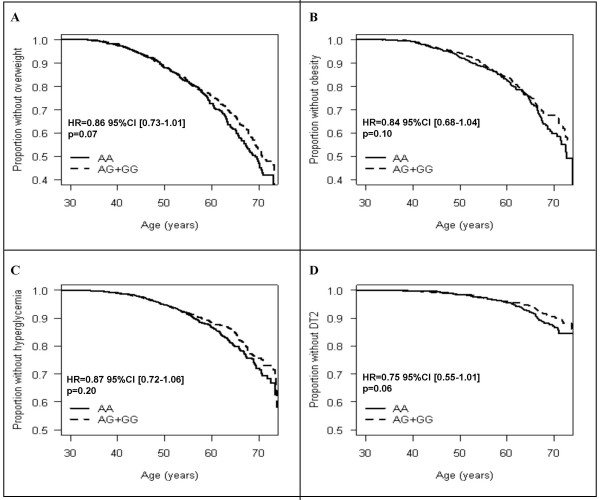

We then aimed to assess if the SNP -1,701A>G modulates traits related to obesity and glucose intolerance in a population-based cohort. Thus, SNP-1,701A>G was also genotyped in 4,922 participants from the D.E.S.I.R prospective study. Cross sectional analyses at baseline did not show an association of SNP -1,701A>G with fasting glucose, fasting insulin, HbA1c levels, HOMA-IR or BMI (data not shown). Only fasting glucose and fasting insulin levels were available for the cohort participants. After 9 years follow-up, allele -1,701G carriers tend to be at lower risk of incidence of overweight (HR = 0.86; p = 0.07), obesity (HR = 0.84; p = 0.10) and T2D (HR = 0.75; p = 0.06) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Hyperglycemia incidence, by age at baseline, in the DESIR population according to SNP -1,701A>G genotype (dominant model). The genotype is considered a risk factor present since birth. The time scale is represented by age (continuous scale). The proportions with overweight (A), obesity (B), hyperglycemia (C) and T2D (D) were calculated within each genotype to assess the impact of SNP-1,701A>G on incidence of all phenotypes studied. Hazard ratios and p values indicated were obtained from Cox proportional hazard survival analyses with age, sex (overweight and obesity) and BMI (hyperglycaemia and T2D) as covariates among AA and AG+GG carriers during the 9 years of follow-up.

Discussion

Here we describe the genetic study of the pituitary peptide 7B2 encoding gene SGNE1, candidate gene for obesity and related metabolic traits. Our study does not provide evidence of association between SGNE1 genetic variation and severe forms of obesity in large populations of French Caucasians, including children and adults. However, one SNP, the -1,701A>G, located in the 5' region of SGNE1, associate with impaired glucose tolerance in the context of severe obesity but does not increase the risk for T2D. A limitation of our study design is that SNP tagging was based on data from HapMap phase I. According to HapMap phase II data [20] genotypes from 18 additional TagSNPs would be necessary for an extensive genetic coverage and comprehensive association analyses of SGNE1 with metabolic diseases.

Our results support that SNP -1,071A>G, although not associated with obesity, may contribute to higher glucose levels after OGTT. Similar findings were previously reported for USF1 (Upstream Stimulatory Factor 1), where SNPs were associated with higher glucose after OGTT, although allelic frequencies were similar between T2D cases and controls [21]. SNP -1,701A>G also associated with higher HOMA-IR and lower insulinogenic index in obese children. As far as adults are concerned, -1,701A allele carriers compensate the decreased insulin secretion capacity over time but their insulin resistance remained impaired. A high proportion (~75%) of our obese adults self-reported overweight since childhood which may explain a shared genetic background of both populations as previously reported [22]. However, their metabolic profile is fairly diverse: 94% of obese children are glucose tolerant after OGTT, against only 52% of the severely obese adults. These data may elucidate the observed heterogeneity between quantitative traits associations in children and adults. We also believe that obesity related quantitative traits results should be interpreted with caution in adults as these analyses are more meaningful in obese children [23].

SNP-1,701A>G is located in intron 1 and is part of the 5' region of SGNE1. It has been shown that intron 1 sequences are essential for transcriptional activity of SGNE1 in human cell lines [24]. A recent study has also shown that intron 1 of SGNE1 is hypermethylated and epigenetically silenced in medulloblastomas [25]. This data supports an important role of intron 1 of SGNE1 and a potential functional role of SNP -1,701A>G in the regulation of SGNE1. According to in silico analyses [26], SNP -1,701A creates a theoretical binding site for TCF/LEF1 (Transcription Factor T-Cell specific/Lymphoid Enhancer binding Factor1). To our knowledge, TCF/LEF1 role in metabolism has not been described. We note that TCF/LEF1 belongs to the Wnt signaling pathway that includes TCL7L2, which harbours highly associated SNPs with T2D [27]. Further molecular studies are required to elucidate how SNP -1,701A>G would affect the expression and function of SGNE1 and ultimately impaired metabolism. An increase of 7B2 has been reported in pancreas from ob/ob mice compared to wild type mice [28] suggesting that 7B2 may increase in insulin resistance state. Thus, as 7B2 is immunologically detected in human plasma [29], analyses of association between SNP -1,701A>G and 7B2 plasma levels in our populations would provide a value indication about how this genetic variant might impact SGNE1 functionality and consequently, glucose tolerance and insulin resistance.

As a protein helper and activator of PC2, 7B2 is involved in the maturation of a large spectrum of molecules playing central roles in weight and glucose homeostasis [5]. 7B2 and PC2 are highly expressed in secretory granules of pancreatic islets and are involved in processing of insulin in β-cells and glucagon in α-cell [5]. High levels of circulating pro-insulin and pro-glucagon have been described in 7B2 knock-out mice confirming the role of 7B2 in insulin and glucagon maturation [30]. If associations and functionality of SNP -1,701A>G are confirmed, we hypothesize that higher glucose levels and lower insulin secretion observed in -1,701A allele carriers could be direct, as a consequence of impairment of the processing and/or secretion of insulin. The observed SNP -1,701A>G associations with higher pro-insulin levels and lower insulinogenic index in obese children support this hypothesis. Insulin secretion could also be indirectly affected through alteration of glucagon processing that requires both PC2 and 7B2. Thus, impairment of glucagon processing may affect insulin secretion and results in increase glucose levels. This hypothesis is supported by a recent study where low circulating glucagon levels accompanied with low 7B2 mRNA and protein levels (but not PC2 levels) were reported in pancreas of a mouse strain highly predisposed to age associated glucose intolerance [31]. Because of the pleitropic function of 7B2, several mechanisms would result from the alteration of its regulation. Other metabolic pathways could also be affected, such as the processing of cholecystokinin (CCK) [32], a gastrointestine peptide that stimulates insulin secretion from β-cells in healthy subjects [33] and the maturation of anorexigenic neuropeptides CART [11] and POMC [10] involved in the regulation of energy balance.

Conclusion

In summary, we report genetic evidence for the role of SGNE1 genetic variation in glucose intolerance and insulin resistance in the background of young onset obesity. Further analyses are required to replicate our findings and to understand the molecular bases of SGNE1 role in the genetic susceptibility to the risk of glucose intolerance in response to glucose load.

Abbreviations

AUC Area under curve

BMI Body mass index

CART Cocaine amphetamine regulated transcript

CCK Cholecystokinin

HOMA-IR Homeostasis model assessment – insulin resistance

IFG Intolerant fasting glucose

NGT Normal glucose tolerant

OGTT Oral glucose tolerance test

PC2 Proprotein convertase 2

PCR Pomymerase chain reaction

POMC Pro-opiomelanocortin

SGNE1 Secretory granule neuroendocrine protein 1

SNP Single nucleotide polymorphism

T2D Type 2 diabetes

TCF/LEF1 Transcription factor t-cell specific/lymphoid enhancer binding factor 1

TCF7L2 Transcription factor t-cell specific 7-like 2

USF1 Upstream Stimulatory Factor 1

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

NBN and VV performed the genotyping. NBN, CL, JV, CP and DM performed the statistical analyses. DNA was provided by GC, BH, JT, MM and BB. NBN drafted the manuscript under PF and DM supervision. DM and PF supervised the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This work was partly supported by the association "200 Familles pour Vaincre le Diabète et l'Obésité", the Association Française des Diabétiques (AFD), an AFERO/Roche research prize. The D.E.S.I.R study was supported by co-operative contracts between INSERM, CNAMTS and Novartis Pharma, INSERM (Réseaux en Santé Publique, Interactions entre les déterminants de la santé), the Association Diabète Risque Vasculaire, the Fédération Française de Cardiologie, La Fondation de France, ALFEDIAM, ONIVINS; Ardix Medical, Bayer Diagnostics, Becton Dickinson, Cardionics, Lilly, Merck Santé, Novo Nordisk, Pierre Fabre, Roche, Sanofi, Topcon. We thank Olfert Landt at Tib-Molbiol, Germany, Cecile Giles and Chantal Samson for technical assistance and Christophe Wachter and Stefan Gaget for bioinformatics assistance. We are indebted to all subjects who volunteered in this study.

Contributor Information

Nabila Bouatia-Naji, Email: nabila.bouatia-naji@good.ibl.fr.

Vincent Vatin, Email: vincent.vatin@good.ibl.fr.

Cécile Lecoeur, Email: cecile@good.ibl.fr.

Barbara Heude, Email: heude@vjf.inserm.fr.

Christine Proença, Email: christine@good.ibl.fr.

Jacques Veslot, Email: jacques.veslot@gmail.com.

Béatrice Jouret, Email: jouret.b@chu-toulouse.fr.

Jean Tichet, Email: jean.tichet@irsa.asso.fr.

Guillaume Charpentier, Email: kerbonac@free.fr.

Michel Marre, Email: michel.marre@bch.ap-hop-paris.fr.

Beverley Balkau, Email: balkau@vjf.inserm.fr.

Philippe Froguel, Email: pfroguel@imperial.ac.uk.

David Meyre, Email: meyre@good.ibl.fr.

References

- Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Bowman BA, Dietz WH, Vinicor F, Bales VS, Marks JS. Prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and obesity-related health risk factors, 2001. Jama. 2003;289:76–79. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss R, Dziura J, Burgert TS, Tamborlane WV, Taksali SE, Yeckel CW, Allen K, Lopes M, Savoye M, Morrison J, Sherwin RS, Caprio S. Obesity and the metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2362–2374. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell CG, Walley AJ, Froguel P. The genetics of human obesity. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:221–234. doi: 10.1038/nrg1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyre D, Lecoeur C, Delplanque J, Francke S, Vatin V, Durand E, Weill J, Dina C, Froguel P. A genome-wide scan for childhood obesity-associated traits in French families shows significant linkage on chromosome 6q22.31-q23.2. Diabetes. 2004;53:803–811. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.3.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbikay M, Seidah NG, Chretien M. Neuroendocrine secretory protein 7B2: structure, expression and functions. Biochem J. 2001;357:329–342. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3570329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidel B, Dong W, Savaria D, Zheng M, Pintar JE, Day R. Neuroendocrine protein 7B2 is essential for proteolytic conversion and activation of proprotein convertase 2 in vivo. DNA Cell Biol. 1998;17:1017–1029. doi: 10.1089/dna.1998.17.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braks JA, Martens GJ. 7B2 is a neuroendocrine chaperone that transiently interacts with prohormone convertase PC2 in the secretory pathway. Cell. 1994;78:263–273. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90296-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuta M, Carroll R, Martin S, Swift HH, Ravazzola M, Orci L, Steiner DF. Incomplete processing of proinsulin to insulin accompanied by elevation of Des-31,32 proinsulin intermediates in islets of mice lacking active PC2. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:3431–3437. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.6.3431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuta M, Zhou A, Webb G, Carroll R, Ravazzola M, Orci L, Steiner DF. Severe defect in proglucagon processing in islet A-cells of prohormone convertase 2 null mice. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:27197–27202. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103362200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent V, Jaubert-Miazza L, Desjardins R, Day R, Lindberg I. Biosynthesis of proopiomelanocortin-derived peptides in prohormone convertase 2 and 7B2 null mice. Endocrinology. 2004;145:519–528. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dey A, Xhu X, Carroll R, Turck CW, Stein J, Steiner DF. Biological processing of the cocaine and amphetamine-regulated transcript precursors by prohormone convertases, PC2 and PC1/3. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:15007–15014. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212128200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergeron F, Sirois F, Mbikay M. ACTH secretion by mouse corticotroph AtT20 cells is negatively modulated by the intracellular level of 7B2. FEBS Lett. 2002;512:259–262. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(02)02277-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarac MS, Zieske AW, Lindberg I. The lethal form of Cushing's in 7B2 null mice is caused by multiple metabolic and hormonal abnormalities. Endocrinology. 2002;143:2324–2332. doi: 10.1210/en.143.6.2324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peinado JR, Laurent V, Lee SN, Peng BW, Pintar JE, Steiner DF, Lindberg I. Strain-dependent influences on the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis profoundly affect the 7B2 and PC2 null phenotypes. Endocrinology. 2005;146:3438–3444. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent V, Kimble A, Peng B, Zhu P, Pintar JE, Steiner DF, Lindberg I. Mortality in 7B2 null mice can be rescued by adrenalectomy: involvement of dopamine in ACTH hypersecretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:3087–3092. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261715099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolland-Cachera MF, Cole TJ, Sempe M, Tichet J, Rossignol C, Charraud A. Body Mass Index variations: centiles from birth to 87 years. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1991;45:13–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tests for deviation from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium and tests for association http://ihg.gsf.de/cgi-bin/hw/hwa1.pl

- Tregouet DA, Escolano S, Tiret L, Mallet A, Golmard JL. A new algorithm for haplotype-based association analysis: the Stochastic-EM algorithm. Ann Hum Genet. 2004;68:165–177. doi: 10.1046/j.1529-8817.2003.00085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudbridge F, Koeleman BP, Todd JA, Clayton DG. Unbiased application of the transmission/disequilibrium test to multilocus haplotypes. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;66:2009–2012. doi: 10.1086/302915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hapmap Hapmap web site. 2005.

- Putt W, Palmen J, Nicaud V, Tregouet DA, Tahri-Daizadeh N, Flavell DM, Humphries SE, Talmud PJ. Variation in USF1 shows haplotype effects, gene : gene and gene : environment associations with glucose and lipid parameters in the European Atherosclerosis Research Study II. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:1587–1597. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouatia-Naji N, Meyre D, Lobbens S, Seron K, Fumeron F, Balkau B, Heude B, Jouret B, Scherer PE, Dina C, Weill J, Froguel P. ACDC/adiponectin polymorphisms are associated with severe childhood and adult obesity. Diabetes. 2006;55:545–550. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.02.06.db05-0971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bougneres P. Genetics of obesity and type 2 diabetes: tracking pathogenic traits during the predisease period. Diabetes. 2002;51 Suppl 3:S295–303. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.2007.S295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gherzi R, Fehmann HC, Eissele R, Goke B. Expression, intracellular localization, and gene transcription regulation of the secretory protein 7B2 in endocrine pancreatic cell lines and human insulinomas. Exp Cell Res. 1994;213:20–27. doi: 10.1006/excr.1994.1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waha A, Koch A, Hartmann W, Milde U, Felsberg J, Hubner A, Mikeska T, Goodyer CG, Sorensen N, Lindberg I, Wiestler OD, Pietsch T, Waha A. SGNE1/7B2 is epigenetically altered and transcriptionally downregulated in human medulloblastomas. Oncogene. 2007 doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartharius K, Frech K, Grote K, Klocke B, Haltmeier M, Klingenhoff A, Frisch M, Bayerlein M, Werner T. MatInspector and beyond: promoter analysis based on transcription factor binding sites. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:2933–2942. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauchi S, Meyre D, Dina C, Choquet H, Samson C, Gallina S, Balkau B, Charpentier G, Pattou F, Stetsyuk V, Scharfmann R, Staels B, Fruhbeck G, Froguel P. Transcription factor TCF7L2 genetic study in the French population: expression in human beta-cells and adipose tissue and strong association with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2006;55:2903–2908. doi: 10.2337/db06-0474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H, Suzuki Y, Ohtake R, Kobori H, Hashigami Y, Shimoda SI. Pituitary, hypothalamic and pancreatic 7B2 concentrations in rats with streptozotocin-induced diabetes and spontaneously diabetic mice. Pancreas. 1988;3:662–667. doi: 10.1097/00006676-198812000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H, Kobori H, Ohtake R, Hashigami Y, Suzuki Y, Shimoda SI, Bloom SR. Circulating concentrations of immunoreactive peptide 7B2 in certain pathophysiological conditions, and response to oral glucose load. Clin Chem. 1988;34:410–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westphal CH, Muller L, Zhou A, Zhu X, Bonner-Weir S, Schambelan M, Steiner DF, Lindberg I, Leder P. The neuroendocrine protein 7B2 is required for peptide hormone processing in vivo and provides a novel mechanism for pituitary Cushing's disease. Cell. 1999;96:689–700. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80579-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt G, Sirois F, Anini Y, Kauri LM, Gyamera-Acheampong C, Fleck E, Scott FW, Chretien M, Mbikay M. Differences of pancreatic expression of 7B2 between C57BL/6J and C3H/HeJ mice and genetic polymorphisms at its locus (Sgne1) Diabetes. 2006;55:452–459. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.02.06.db05-0733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehfeld JF, Lindberg I, Friis-Hansen L. Increased synthesis but decreased processing of neuronal proCCK in prohormone convertase 2 and 7B2 knockout animals. J Neurochem. 2002;83:1329–1337. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederau C, Schwarzendrube J, Luthen R, Niederau M, Strohmeyer G, Rovati L. Effects of cholecystokinin receptor blockade on circulating concentrations of glucose, insulin, C-peptide, and pancreatic polypeptide after various meals in healthy human volunteers. Pancreas. 1992;7:1–10. doi: 10.1097/00006676-199201000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]