Abstract

Notch signaling influences a variety of cell fate decisions during development, and constitutive activation of the pathway can provoke unbridled cell growth and cancer. The mechanisms by which Notch affects cell growth are not well established. We describe here a novel link between Notch and cell cycle control. We found that Mv1Lu epithelial cells harboring an oncogenic form of Notch (NICD) are resistant to the cell cycle-inhibitory effects of transforming growth factor β (TGF-β). NICD did not affect TGF-β signaling per se but blocked induction of the Cdk inhibitor p15INK4B. c-Myc, whose down-regulation by TGF-β is required for p15INK4B induction, remained elevated in the NICD-expressing cells. c-Myc expression was also maintained in low serum, indicating that Notch's effects on c-Myc are not specific to TGF-β. Our results are consistent with a model in which a strong Notch signal indirectly deregulates c-Myc expression and thereby renders Mv1Lu epithelial cells resistant to growth-inhibitory signals.

Notch signaling specifies cell fate decisions in a variety of tissues during development (1, 2). Activation of the pathway in vertebrates begins with the binding of Notch to its ligand, Delta or Jagged, which stimulates TACE and presenilin-mediated proteolysis (27). These cleavage events release the intracellular domain of Notch, NICD, from the plasma membrane and allow its transit into the nucleus where it interacts with the DNA binding protein CSL and activates transcription (20). Mutations in Notch pathway components are associated with developmental disorders that affect diverse tissues, including bone, blood, liver, and vascular tissue (19, 22, 23, 28, 32, 33). Notch has also been implicated in human cancer as well as cancers induced by retroviral insertions in mice (11, 18, 30, 34). In the situations described thus far, tumorigenesis is associated with unregulated expression of a form of Notch functionally equivalent to NICD. However, NICD is not a classic oncogene; the effects of Notch are exquisitely cell type dependent, and the pathways that mediate growth and transformation are not known. Several reports have documented the sensitivity of T cells to Notch-mediated transformation (4, 11, 30, 34), and there is increasing evidence that epithelial tissues can also be transformed by activated Notch (9, 18, 46). Notch has also been proposed to be a critical player in the transformation of human cells, including epithelial cells, by activated Ras (43).

Transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) is an antimitogenic cytokine. Signaling begins with the engagement of receptors at the cell surface, followed by the phosphorylation of cytoplasmic Smad proteins (R-Smads) (25). The R-Smads then enter the nucleus where they typically activate transcription as heterodimers with Smad4. Although these heterodimers can bind DNA, transcriptional activation usually requires their association with distinct DNA binding proteins. TGF-β arrests cells in the G1 phase of the cell cycle by inducing the expression of the Cdk inhibitors p15INK4B and p21 (10, 15). However, since c-Myc dominantly represses the p15INK4B promoter (12, 37, 39, 42), induction of p15INK4B requires the coordinate down-regulation of c-Myc transcription by TGF-β. In this case, TGF-β induces the formation of a repressive complex at the c-Myc promoter, consisting of E2F4/E2F5, p107, and Smad3 (8). Elevated or constitutive expression of c-Myc negates the ability of TGF-β to induce p15INK4B and thereby blocks TGF-β's cytostatic effects.

Epithelial tissues utilize the TGF-β signaling pathway for homeostasis, and a number of epithelial tumors are resistant to the cytostatic effects of TGF-β (26). Accordingly, in this study we sought to determine whether Notch can influence the response of epithelial cells to TGF-β. We show that the intracellular form of Notch, NICD, renders mink lung epithelial cells resistant to the effects of TGF-β without affecting TGF-β signaling per se. Our data are consistent with a model in which a strong Notch signal deregulates expression of c-Myc and thereby renders epithelial cells resistant to growth-inhibitory signals.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and viruses.

The NICD-expressing retrovirus was generated by isolating a PmeI-XhoI fragment from the Notch expression plasmid NICD (36) and cloning it into MigR1 (31). Mv1Lu cells (ATCC catalog no. CCL-64) and their corresponding derivatives were cultured in high-glucose Dulbecco modified Eagle medium containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) supplemented with penicillin and streptomycin. Cells were infected with retroviruses (MigR1 or NICD) generated by calcium phosphate-mediated, triple-plasmid transfection (gag-pol, vesicular stomatitis virus G, and retroviral constructs) of 293T cells. Green fluorescent protein (GFP) served as a surrogate marker for identifying infected cells. Purified TGF-β was obtained from BD Biosciences (Bedford, Mass.) (catalog no. 334039). Treatment times are indicated in the figures or figure legends. For cell cycle analysis, ModFit software was used to model populations of cells using DNA content from propidium iodine-stained cells as a criterion. Cross-linking of 125I-labeled TGF-β (Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences, Boston, Mass.) was performed as described previously (41).

RNA analysis.

RNA was extracted from cells using Tri-Reagent (catalog no. T 9424; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) per the manufacturer's instructions. For Northern blots, 10 to 20 μg of total RNA was resolved using glyoxal gels (Ambion Inc., Austin, Tex.). DNAs corresponding to human c-myc (a gift from W. El-Diery, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine) and rat glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were used to generate radiolabeled cDNA probes for detection. Primer sequences used for reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) were as follows: for mink plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1), 5′-GCCTGGCCCTTGTCTTTGGTG-3′ and 5′-TTCCCTTTCCACTGGCTGATG-3′; for mink GAPDH, 5′-CCTCCTGTACCACCAACTGCT-3′ and 5′-GATGCCTGCTTCACCACCTTC-3′. Amplicon lengths and annealing temperatures were 349 bp and 59°C for GAPDH and 827 bp and 59°C for PAI-1. PCRs were performed in the presence of trace amounts of [32P]dATP.

Western blots and immunoprecipitations.

Cdk4 (sc-260), cyclin A (sc-951), and p15INK4B (sc-612) antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, Calif.). Retinoblastoma protein (Rb) antibody (554136) was obtained from BD Biosciences (Palo Alto, Calif.). Smad2 antibody (3107) and phosphorylated Smad2 (564413) antibody were from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, Mass.) and Calbiochem (San Diego, Calif.), respectively. Immune complexes were revealed by chemiluminescence. Cdk2 kinase assays were performed in kinase buffer (20 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 2.5 mM MnCl2) supplemented with 1 mM dithiothreitol, 10 μM cold ATP, 5 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP (3,000 Ci/mmol), 2 μg of histone H1, and phosphatase and protease inhibitors after immunoprecipitation in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.1% NP-40, and phosphatase and protease inhibitors). Five hundred micrograms of total protein was used per immunoprecipitation using a Cdk2 antibody from Santa Cruz (sc-163).

RESULTS

NICD inhibits TGF-β-induced cell cycle arrest.

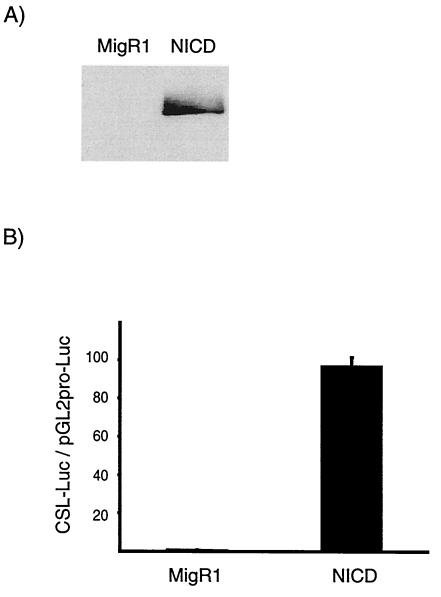

The TGF-β-sensitive cell line Mv1Lu was transduced with a control retroviral vector (MigR1) or with a retrovirus encoding intracellular Notch (NICD). GFP is also encoded by the viruses and served as a marker for virus-infected cells and as a surrogate marker for NICD expression. NICD expression was stable in the Mv1Lu cells, but not in two other TGF-β-sensitive cell lines, HaCaT and Hep3B (P. Rao, unpublished observations). The transduction efficiency of the Mv1Lu cells was very high (virtually 100%), suggesting that we had not selected a small subpopulation of NICD-resistant cells. Western blot analysis confirmed that the cells expressed NICD protein (Fig. 1A). Transfection assays indicated that they supported activity of a reporter under the control of a promoter containing binding sites for the Notch-responsive DNA binding protein CSL (Fig. 1B). Control GFP-positive cells, transduced with the parental virus MigR1, did not express NICD and did not support activity of the Notch-responsive reporter.

FIG. 1.

Transduction and expression of activated human Notch1 in Mv1Lu cells. (A) Expression of NICD in cells transduced with activated, intracellular human Notch1 was confirmed by Western blot analysis (antibody from Spyros Artavanis-Tsakonas). (B) (CSL)4-luciferase (17) and pGL2pro-luciferase reporters were transfected into MigR1- and NICD-transduced cells, and luciferase activity was determined 48 h later. Robust expression from the (CSL)4 luciferase reporter vector was detected in NICD-transduced cells but not in MigR1-transduced cells.

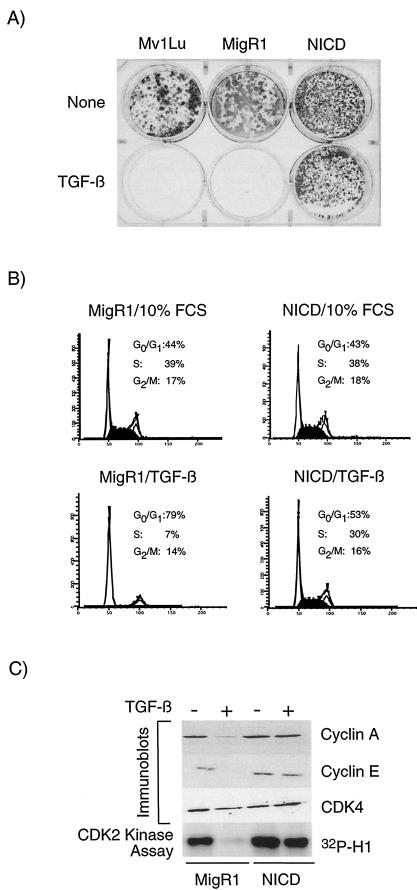

We first assessed the relationship between NICD and TGF-β with a colony-forming assay. Parental Mv1Lu cells (no virus) and MigR1-transduced Mv1Lu cells were not able to form colonies with sustained exposure to TGF-β. In contrast, NICD-transduced cells were completely resistant to the inhibitory effects of TGF-β (Fig. 2A). Given the complete lack of TGF-β-resistant colonies in the parental and MigR1-transduced cells, the effect of NICD cannot be due to viral integration effects or to the selection of a cell population predisposed to TGF-β resistance. We would argue instead that NICD itself renders the cells resistant to TGF-β.

FIG.2.

NICD transduction renders epithelial cells resistant to the growth-inhibitory effects of TGF-β. (A) 4 × 103 parental cells (Mv1Lu) and MigR1- and NICD-transduced cells were treated with 10% FCS (top row) or with 50 pM TGF-β in 10% FCS (bottom row). The medium was changed every other day, and the plate was stained after 9 days. (B) Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis for DNA content was performed on MigR1- or NICD-transduced cells after control (10% FCS) treatment or with 200 pM TGF-β (in 10% FCS) treatment for 20 h. G1 and G2 peaks are unshaded; the intervening S-phase population is shown in black. Percentages of cells in each population are indicated. A representative profile is shown. (C) Lysates from cells treated as described above for panel B were probed with cyclin A, Cdk4, and Notch1 antibodies and used for Cdk2 kinase assays. An irrelevant, species-matched antibody did not pull down kinase activity (data not shown).

TGF-β inhibits growth by arresting cells at the G1 phase of the cell cycle. To determine whether NICD overcomes G1 arrest, we treated MigR1- or NICD-transduced cells with TGF-β for 24 h and examined cell cycle profiles. Unlike MigR1-transduced cells, NICD-transduced cells did not arrest in G1 in the presence of TGF-β (Fig. 2B). NICD-transduced cells showed a slight increase in the steady-state S-phase population but grew somewhat more slowly than MigR1-transduced cells (data not shown) and did not appear to be morphologically transformed. Hence, the TGF-β resistance of NICD-transduced cells is not due to an increase in the proliferation rate per se. Western blot analyses (Fig. 2C) revealed a marked, TGF-β-dependent decrease in the levels of cyclin A and cyclin E (data not shown) relative to that of Cdk4 in MigR1-transduced cells. No such decline was evident in the NICD-transduced cells, thereby confirming the fluorescence-activated cell sorting data. Cdk2-associated kinase activity remained high in NICD-expressing cells treated with TGF-β (Fig. 2C). Although cyclin D1 has been proposed to be a direct target of Notch (35), we did not observe an increase in the steady-state levels of D-type cyclins in NICD-transduced cells. Instead, we observed an unexpected decline in the level of cyclin D1 protein (data not shown).

TGF-β signaling is intact in NICD-transduced cells.

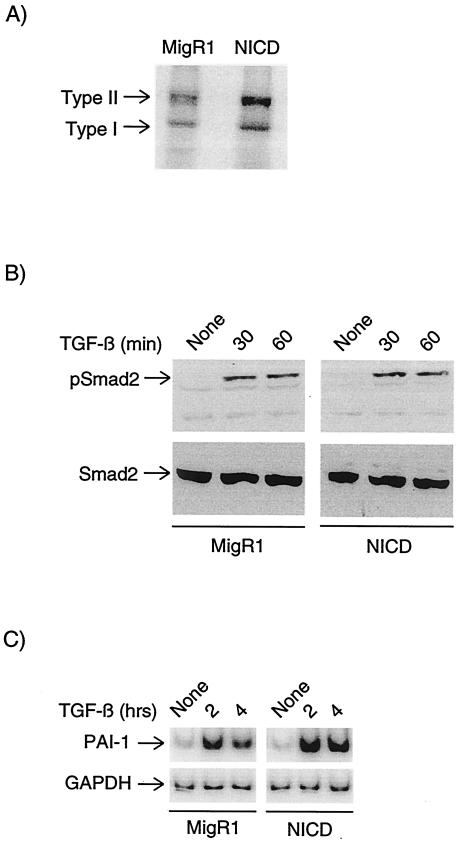

TGF-β signaling initiates with the engagement of type I and type II receptors, followed by the phosphorylation of Smad2/3 proteins, nuclear translocation, and transcriptional activation (26). To determine whether the TGF-β-resistant phenotype conferred by NICD was due to the disruption of receptor-mediated events, we examined the ability of TGF-β to bind its receptors and induce the phosphorylation of Smad2. Receptor levels were assessed by cross-linking 125I-labeled TGF-β to MigR1- and NICD-transduced cells and then resolving labeled proteins by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Binding to both the type I and type II receptors was roughly equivalent in the two cell types (Fig. 3A). Both cell types also responded appropriately to TGF-β receptor engagement as measured by the appearance of phosphorylated Smad2 (Fig. 3B). Overall levels of Smad2 were unchanged. To assess the ability of Smad proteins to activate transcription, we monitored the ability of TGF-β to activate transcription of PAI-1, a well-characterized TGF-β- and Smad-responsive gene. Semiquantitative RT-PCR assays revealed that transcriptional induction of the endogenous PAI-1 gene was similar in MigR1- and NICD-transduced cells (Fig. 3C). On the basis of these observations, we conclude that the core TGF-β signaling cascade is intact in NICD-transduced cells. Moreover, Smad activation per se is not sufficient to mediate growth arrest in NICD-transduced cells.

FIG. 3.

NICD expression does not affect Smad activation. (A) Lysates from MigR1- and NICD-transduced cells cross-linked with 125I-labeled TGFβ were resolved by SDS-PAGE. Cross-linked receptors (type I and type II) were identified by autoradiography. (B) MigR1- and NICD-transduced cell lysates were treated with TGFβ for the indicated times, and cell lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and assayed for Smad2 phosphorylation with phosphorylated Smad2 (pSmad2) and total Smad2 antibodies. (C) PAI-1 was assayed by semiquantitative RT-PCR using RNA extracted from MigR1- and NICD-transduced cells treated with TGFβ for the indicated times. Amplification using GAPDH primers served as a control for input RNA.

NICD disrupts c-Myc regulation.

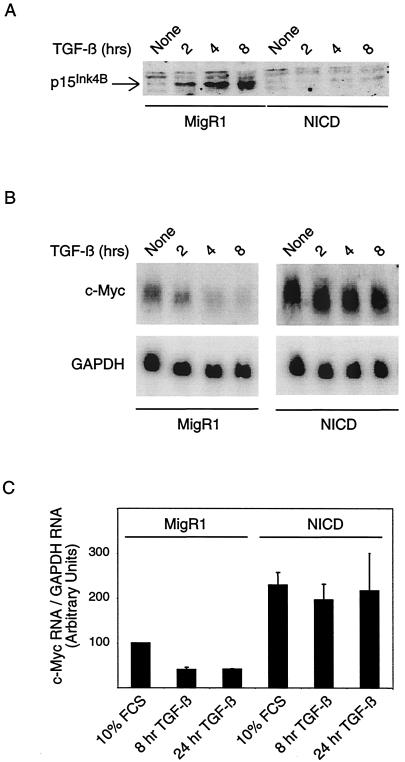

TGF-β-mediated growth arrest occurs through the rapid inhibition of kinases required for the G1-S transition. The Cdk inhibitor p15INK4B is particularly important for G1 arrest and is a direct transcriptional target of activated Smads (13). Given its central role in the TGF-β cytostatic response, we examined the induction of p15INK4B in NICD-transduced cells. TGF-β generated a rapid and robust induction of p15INK4B protein in MigR1-transduced cells. In contrast, p15INK4B was not induced in NICD-transduced cells (Fig. 4A). These data indicate that, despite the presence of Smad binding sites within the p15INK4B promoter, Smad activation is not sufficient to induce p15INK4B in NICD-transduced cells.

FIG. 4.

NICD-transduced cells fail to induce p15INK4B and down-regulate c-Myc. (A) Western blot analysis for p15INK4B was performed on lysates from MigR1- and NICD-transduced cells treated with TGF-β for the indicated times. (B) c-Myc transcript levels were detected by Northern blot analysis on RNA obtained from TGF-β-treated MigR1- and NICD-transduced cells. The membrane was stripped and reprobed with a GAPDH probe to ensure equal loading of RNA. (C) c-Myc and GAPDH RNAs from three separate Northern blot analyses were quantitated with a phosphorimager and expressed as a ratio (the level of c-Myc in normal cells was arbitrarily set at 100).

Another key player in the orchestration of the TGF-β cytostatic program is the proto-oncogene c-Myc. TGF-β actively represses c-Myc transcription through a Smad3/E2F4/p107 complex formed at the c-Myc promoter (8, 45). c-Myc repression is critical for full p15INK4B induction, since c-Myc dominantly interferes with p15INK4B transcription (12, 37, 39, 42). Expression of c-Myc from a heterologous promoter negates TGF-β-mediated induction of p15INK4B, but not of other TGF-β-responsive genes (12). Since NICD-transduced cells displayed a profile similar to that obtained with c-Myc overexpression, we monitored the effect of NICD on c-Myc. As expected, TGF-β treatment led to a rapid reduction in the level of c-Myc transcripts in MigR1-transduced cells (Fig. 4B). However, during the short time examined, c-Myc RNA levels were sustained in NICD-transduced cells treated with TGF-β. In the course of these experiments, we noticed that the basal levels of c-Myc were generally higher (roughly two- to threefold) in the NICD-transduced cells than in the MigR1-transduced cells (Fig. 4C). Although Notch and c-Myc have been shown to collaborate to induce transformation under certain conditions (14), these results are the first to show that NICD can specifically deregulate c-Myc expression.

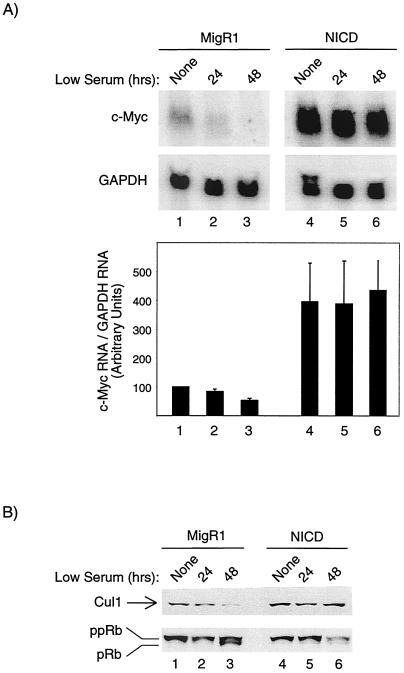

Transcriptional regulation of c-Myc is complex. In addition to the repression mediated by TGF-β, c-Myc expression is also reduced under conditions of low serum. We reasoned that the deregulation of c-Myc by NICD could be due either to an inability to generate a functional repressor complex, as seen in Ras/ErbB2-transformed mammary cells (7), or to changes that are independent of TGF-β. To determine whether the effect of NICD is independent of TGF-β, we placed MigR1- and NICD-transduced cells in low serum and monitored c-Myc levels over time. As expected, c-Myc RNA levels decreased when MigR1-transduced cells were switched from high to low serum. In contrast, c-Myc transcripts in NICD-transduced cells were insensitive to low serum (Fig. 5A). Expression of Cul1, a purported target of c-Myc (29), was also sustained in the NICD-transduced cells in low serum (Fig. 5B). Although the precise mechanism is still debated, c-Myc expression allows for enhanced cyclinE/Cdk2 activity by interfering with p27 function. (Note that Cul1 is a component of SCF, a ubiquitin ligase complex that targets p27.) This would place c-Myc upstream of pocket proteins Rb, p107, and p130 and argue that Rb should be hyperphosphorylated whenever c-Myc levels are elevated. Consistent with this prediction, hypophosphorylated Rb accumulated when MigR1 cells were placed in low serum, but Rb remained hyperphosphorylated in NICD-transduced cells (Fig. 5C).

FIG. 5.

NICD expression sustains high c-Myc levels and maintains Rb in a hyperphosphorylated state in low serum. (A) MigR1- and NICD-transduced cells were placed under conditions of low serum (0.1% serum) for the indicated times. RNA harvested from these cells was subjected to Northern blot analysis to sequentially detect c-Myc and GAPDH transcripts. In the graph, RNAs from three separate experiments were quantitated as described in the legend to Fig. 4. (B) Cells were treated as described above for panel A, and a Western blot was performed to detect Cul1 and Rb. The positions of Cul1 and hyper- and hypophosphorylated Rb (ppRb and pRb, respectively) are shown to the left of the blots. In both panels, “None” indicates growth in 10% serum.

Taken together, these data indicate that the effect of NICD on c-Myc expression is general and not restricted to the context of TGF-β signaling. However, our data also suggest that the effect of Notch on c-Myc is not simple and is cell type dependent. For example, neither C2C12 myoblasts nor NIH 3T3 fibroblasts transduced with NICD displayed elevated levels of c-Myc (data not shown). HaCaT keratinocytes and MCF10A mammary cells did not tolerate elevated expression of NICD and so did not permit an evaluation of Notch's effects on c-Myc in other epithelial cell types. Furthermore, cotransfection experiments with NICD and reporters under the control of the c-Myc promoter failed to demonstrate a direct effect of Notch on c-Myc transcription. Also, while c-Myc promoter activity was generally higher in the NICD-transduced Mv1Lu cells, we were unable to locate a clear stimulatory element with a series of c-Myc promoter deletions (data not shown). We propose that high levels of Notch signaling exert indirect and subtle effects on the c-Myc promoter and/or mRNA that are revealed under conditions conducive to c-Myc down-regulation.

Constitutive expression of NICD is thought to generate levels of signaling significantly higher than those obtained when Notch is activated by ligand. Indeed, ligand-mediated effects are typically associated with normal developmental processes, while constitutive expression of NICD can result in cancer. We therefore asked whether the Notch ligand Jagged1 could also eliminate the effects of TGF-β. Mv1Lu cells were cocultured with NIH 3T3 fibroblasts that had been transduced with either MigR1 or a Jagged1-expressing retrovirus. After 3 days, the mixed cultures were treated with TGF-β (8 h), NIH 3T3 cells were removed (by virtue of a H2Kk surface marker; D. A. Ross and T. Kadesch, unpublished data), and p15 expression was assessed in the remaining Mv1Lu cells. While Jagged1 induced the expression of cleaved Notch in the Mv1Lu cells, it did not alter the ability of TGF-β to induce p15 (data not shown). These results argue that the effects we observe may be limited to high levels of Notch signaling.

DISCUSSION

We have used an oncogenic form of Notch, NICD, to examine the relationship between Notch signaling and growth control. Our data are consistent with a model in which high levels of Notch signaling somehow deregulate c-Myc transcription such that cells no longer respond appropriately to growth-inhibitory signals. Although NICD may have effects on genes other than c-Myc, the changes we observe in c-Myc are sufficient to explain the resistance to TGF-β. This effect of NICD on c-Myc is most likely indirect, since NICD does not activate the 2.5-kb c-Myc promoter (16) directly and does not increase c-Myc expression in all cell types. In support of our observations, deregulation of c-Myc also occurs in the presence of EBNA2 (21), which can mimic activated Notch by binding to CSL. Retroviral transduction of NICD results in relatively high levels of Notch signaling, higher than those typically found when Notch is activated by ligand. Accordingly, we cannot conclude that the effects we observe are relevant to Notch's effects on development. However, the levels we see are comparable to those observed in SupT1 cells, which were derived from a human T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia patient expressing the t(7;9)(q34;q34.3) translocation and, accordingly, express intracellular Notch constitutively (11). Our data are not consistent with the possibility that long-term NICD overexpression, which can be deleterious to a variety of cell types, selects for those Mv1Lu cells that stably express higher levels of c-Myc. Long-term exposure of cells to TGF-β provided no evidence for such a population.

Notch has been shown to interact with several other signaling pathways during development. Many of these interactions are cell type dependent, suggesting that the interactions are either indirect or modulated by cell-specific cofactors. In most cases, a molecular explanation for the interaction is lacking. The interplay between the Notch and Wingless pathways has been proposed to involve direct interactions between components of the pathways so that Wingless can either antagonize (3) or promote (24, 44) Notch signaling. Interactions between Notch and Ras can also be either cooperative or antagonistic. However, the only molecular mechanism described thus far involves the demonstration that Notch can activate expression of a mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase (LIP-1) and hence antagonize Ras signaling during vulval induction in Caenorhabditis elegans (5). Only one other study has provided evidence for an interaction between Notch and TGF-β. In this case, an activated form of Notch4 was shown to inhibit TGF-β2-induced branching morphogenesis of TAC-2 mammary epithelial cells in culture (40). The molecular basis for this effect has not been investigated. It is reasonable to assume that many of the interactions described for Notch and other signaling pathways involve convergence at the level of target gene expression as opposed to the interactions between the pathways themselves. This is apparently the case for Notch and Hedgehog, where both proteins activate expression of the Hes1 gene to block differentiation of cerebellar granule neuron precursor cells (38). Consistent with this idea, our data show that NICD does not affect TGF-β signaling per se but affects a gene, c-Myc, that represses a particular target of TGF-β signaling, namely, p15INK4B. Since some of the effects of TGF-β in vivo do not involve growth suppression, we would not expect that Notch would affect all TGF-β-mediated responses.

The present evidence linking Notch to c-Myc would suggest they operate in distinct, complementary pathways. Truncated Notch genes were found to reduce the latency of MMTVD/myc-induced thymomas in mice (14) and could therefore function as a second, collaborating hit in the production of the tumors. E1A, which shares many properties with c-Myc in inducing cellular transformation, is necessary for NICD to transform rat kidney cells in vitro (6); however, it has not been determined whether c-Myc can functionally replace E1A in this assay. Our data would place Notch upstream of c-Myc with both proteins residing in the same pathway. However, given the cell type-specific nature of Notch's effects and the fact that our data apply thus far only to epithelial cells, it is feasible that oncogenic Notch influences different pathways in different cell types. Recent evidence supports the hypothesis that Notch is universally required for Ras-mediated transformation of a variety of human cell types, including epithelial cells (43). Although it remains to be determined exactly how Notch supports Ras-mediated transformation, it is tempting to speculate that it is through Notch’s ability to deregulate c-Myc.

Our results implicate c-Myc as a potentially important player in Notch-mediated growth control in epithelial cells and possibly in Notch-mediated oncogenesis. It is well-known that the effects of Notch, including oncogenicity, are extremely cell type dependent, and it is tempting to speculate that Notch-mediated transformation mirrors cell type-specific deregulation of c-Myc. Noteworthy in this regard are observations concerning the ability of activated Notch4 to transform glandular epithelia, such as mammary and salivary glands. Mammary gland epithelial cells utilize c-Myc to override TGF-β-mediated growth arrest (7). A recent study has reported elevated expression of Notch4 in pancreatic adenocarcinoma (9), another cancer in which TGF-β pathway alterations are common. These examples raise the intriguing possibility that Notch may induce tumorigenesis in some cell types exclusively through the deregulation of c-Myc and the concomitant generation of TGF-β resistance.

Acknowledgments

P.R. thanks members of the Kadesch laboratory, X. Hua, and L. Julie Huber for invaluable discussions. We thank W. S. Pear for helpful discussions and for providing the MigR1 retroviral vector.

This work was supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (RO1 GM58228) to T.K. and by NIH Predoctoral Training Grant Program in Genetics (T32 GM08216) and NIH training grant in immunobiology of normal and neoplastic lymphocytes (CA 09140) to P.R.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allman, D., J. A. Punt, D. J. Izon, J. C. Aster, and W. S. Pear. 2002. An invitation to T and more: notch signaling in lymphopoiesis. Cell 109(Suppl.):S1-S11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Artavanis-Tsakonas, S., M. D. Rand, and R. J. Lake. 1999. Notch signaling: cell fate control and signal integration in development. Science 284:770-776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Axelrod, J. D., K. Matsuno, S. Artavanis-Tsakonas, and N. Perrimon. 1996. Interaction between Wingless and Notch signaling pathways mediated by dishevelled. Science 271:1826-1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bellavia, D., A. F. Campese, E. Alesse, A. Vacca, M. P. Felli, A. Balestri, A. Stoppacciaro, C. Tiveron, L. Tatangelo, M. Giovarelli, C. Gaetano, L. Ruco, E. S. Hoffman, A. C. Hayday, U. Lendahl, L. Frati, A. Gulino, and I. Screpanti. 2000. Constitutive activation of NF-κB and T-cell leukemia/lymphoma in Notch3 transgenic mice. EMBO J. 19:3337-3348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berset, T., E. F. Hoier, G. Battu, S. Canevascini, and A. Hajnal. 2001. Notch inhibition of RAS signaling through MAP kinase phosphatase LIP-1 during C. elegans vulval development. Science 291:1055-1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Capobianco, A. J., P. Zagouras, C. M. Blaumueller, S. Artavanis-Tsakonas, and J. M. Bishop. 1997. Neoplastic transformation by truncated alleles of human NOTCH1/TAN1 and NOTCH2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:6265-6273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen, C. R., Y. Kang, and J. Massague. 2001. Defective repression of c-myc in breast cancer cells: a loss at the core of the transforming growth factor beta growth arrest program. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:992-999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, C. R., Y. Kang, P. M. Siegel, and J. Massague. 2002. E2F4/5 and p107 as Smad cofactors linking the TGFbeta receptor to c-myc repression. Cell 110:19-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crnogorac-Jurcevic, T., E. Efthimiou, T. Nielsen, J. Loader, B. Terris, G. Stamp, A. Baron, A. Scarpa, and N. R. Lemoine. 2002. Expression profiling of microdissected pancreatic adenocarcinomas. Oncogene 21:4587-4594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Datto, M. B., Y. Li, J. F. Panus, D. J. Howe, Y. Xiong, and X. F. Wang. 1995. Transforming growth factor beta induces the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 through a p53-independent mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:5545-5549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ellisen, L. W., J. Bird, D. C. West, A. L. Soreng, T. C. Reynolds, S. D. Smith, and J. Sklar. 1991. TAN-1, the human homolog of the Drosophila notch gene, is broken by chromosomal translocations in T lymphoblastic neoplasms. Cell 66:649-661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feng, X. H., Y. Y. Liang, M. Liang, W. Zhai, and X. Lin. 2002. Direct interaction of c-Myc with Smad2 and Smad3 to inhibit TGF-beta-mediated induction of the CDK inhibitor p15Ink4B. Mol. Cell 9:133-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feng, X. H., X. Lin, and R. Derynck. 2000. Smad2, Smad3 and Smad4 cooperate with Sp1 to induce p15Ink4B transcription in response to TGF-beta. EMBO J. 19:5178-5193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Girard, L., Z. Hanna, N. Beaulieu, C. D. Hoemann, C. Simard, C. A. Kozak, and P. Jolicoeur. 1996. Frequent provirus insertional mutagenesis of Notch1 in thymomas of MMTVD/myc transgenic mice suggests a collaboration of c-myc and Notch1 for oncogenesis. Genes Dev. 10:1930-1944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hannon, G. J., and D. Beach. 1994. p15INK4B is a potential effector of TGF-beta-induced cell cycle arrest. Nature 371:257-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.He, T. C., A. B. Sparks, C. Rago, H. Hermeking, L. Zawel, L. T. da Costa, P. J. Morin, B. Vogelstein, and K. W. Kinzler. 1998. Identification of c-MYC as a target of the APC pathway. Science 281:1509-1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsieh, J. J., T. Henkel, P. Salmon, E. Robey, M. G. Peterson, and S. D. Hayward. 1996. Truncated mammalian Notch1 activates CBF1/RBPJk-repressed genes by a mechanism resembling that of Epstein-Barr virus EBNA2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:952-959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jhappan, C., D. Gallahan, C. Stahle, E. Chu, G. H. Smith, G. Merlino, and R. Callahan. 1992. Expression of an activated Notch-related int-3 transgene interferes with cell differentiation and induces neoplastic transformation in mammary and salivary glands. Genes Dev. 6:345-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joutel, A., C. Corpechot, A. Ducros, K. Vahedi, H. Chabriat, P. Mouton, S. Alamowitch, V. Domenga, M. Cecillion, E. Marechal, J. Maciazek, C. Vayssiere, C. Cruaud, E. A. Cabanis, M. M. Ruchoux, J. Weissenbach, J. F. Bach, M. G. Bousser, and E. Tournier-Lasserve. 1996. Notch3 mutations in CADASIL, a hereditary adult-onset condition causing stroke and dementia. Nature 383:707-710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kadesch, T. 2000. Notch signaling: a dance of proteins changing partners. Exp. Cell Res. 260:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaiser, C., G. Laux, D. Eick, N. Jochner, G. W. Bornkamm, and B. Kempkes. 1999. The proto-oncogene c-myc is a direct target gene of Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 2. J. Virol. 73:4481-4484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kusumi, K., E. S. Sun, A. W. Kerrebrock, R. T. Bronson, D. C. Chi, M. S. Bulotsky, J. B. Spencer, B. W. Birren, W. N. Frankel, and E. S. Lander. 1998. The mouse pudgy mutation disrupts Delta homologue Dll3 and initiation of early somite boundaries. Nat. Genet. 19:274-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li, L., I. D. Krantz, Y. Deng, A. Genin, A. B. Banta, C. C. Collins, M. Qi, B. J. Trask, W. L. Kuo, J. Cochran, T. Costa, M. E. Pierpont, E. B. Rand, D. A. Piccoli, L. Hood, and N. B. Spinner. 1997. Alagille syndrome is caused by mutations in human Jagged1, which encodes a ligand for Notch1. Nat. Genet. 16:243-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martinez Arias, A. 1998. Interactions between Wingless and Notch during the assignment of cell fates in Drosophila. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 42:325-333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Massague, J. 2000. How cells read TGF-beta signals. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1:169-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Massague, J., S. W. Blain, and R. S. Lo. 2000. TGFbeta signaling in growth control, cancer, and heritable disorders. Cell 103:295-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mumm, J. S., and R. Kopan. 2000. Notch signaling: from the outside in. Dev. Biol. 228:151-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oda, T., A. G. Elkahloun, B. L. Pike, K. Okajima, I. D. Krantz, A. Genin, D. A. Piccoli, P. S. Meltzer, N. B. Spinner, F. S. Collins, and S. C. Chandrasekharappa. 1997. Mutations in the human Jagged1 gene are responsible for Alagille syndrome. Nat. Genet. 16:235-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Hagan, R. C., M. Ohh, G. David, I. M. de Alboran, F. W. Alt, W. G. Kaelin, Jr., and R. A. DePinho. 2000. Myc-enhanced expression of Cul1 promotes ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis and cell cycle progression. Genes Dev. 14:2185-2191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pear, W. S., J. C. Aster, M. L. Scott, R. P. Hasserjian, B. Soffer, J. Sklar, and D. Baltimore. 1996. Exclusive development of T cell neoplasms in mice transplanted with bone marrow expressing activated Notch alleles. J. Exp. Med. 183:2283-2291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pear, W. S., J. P. Miller, L. Xu, J. C. Pui, B. Soffer, R. C. Quackenbush, A. M. Pendergast, R. Bronson, J. C. Aster, M. L. Scott, and D. Baltimore. 1998. Efficient and rapid induction of a chronic myelogenous leukemia-like myeloproliferative disease in mice receiving P210 bcr/abl-transduced bone marrow. Blood 92:3780-3792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pui, J. C., D. Allman, L. Xu, S. DeRocco, F. G. Karnell, S. Bakkour, J. Y. Lee, T. Kadesch, R. R. Hardy, J. C. Aster, and W. S. Pear. 1999. Notch1 expression in early lymphopoiesis influences B versus T lineage determination. Immunity 11:299-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Radtke, F., A. Wilson, G. Stark, M. Bauer, J. van Meerwijk, H. R. MacDonald, and M. Aguet. 1999. Deficient T cell fate specification in mice with an induced inactivation of Notch1. Immunity 10:547-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rohn, J. L., A. S. Lauring, M. L. Linenberger, and J. Overbaugh. 1996. Transduction of Notch2 in feline leukemia virus-induced thymic lymphoma. J. Virol. 70:8071-8080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ronchini, C., and A. J. Capobianco. 2001. Induction of cyclin D1 transcription and CDK2 activity by Notch(ic): implication for cell cycle disruption in transformation by Notch(ic). Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:5925-5934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ross, D. A., and T. Kadesch. 2001. The notch intracellular domain can function as a coactivator for LEF-1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:7537-7544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seoane, J., C. Pouponnot, P. Staller, M. Schader, M. Eilers, and J. Massague. 2001. TGFbeta influences Myc, Miz-1 and Smad to control the CDK inhibitor p15INK4b. Nat. Cell. Biol. 3:400-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Solecki, D. J., X. L. Liu, T. Tomoda, Y. Fang, and M. E. Hatten. 2001. Activated Notch2 signaling inhibits differentiation of cerebellar granule neuron precursors by maintaining proliferation. Neuron 31:557-568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Staller, P., K. Peukert, A. Kiermaier, J. Seoane, J. Lukas, H. Karsunky, T. Moroy, J. Bartek, J. Massague, F. Hanel, and M. Eilers. 2001. Repression of p15INK4b expression by Myc through association with Miz-1. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:392-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Uyttendaele, H., J. V. Soriano, R. Montesano, and J. Kitajewski. 1998. Notch4 and Wnt-1 proteins function to regulate branching morphogenesis of mammary epithelial cells in an opposing fashion. Dev. Biol. 196:204-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang, X. F., H. Y. Lin, E. Ng-Eaton, J. Downward, H. F. Lodish, and R. A. Weinberg. 1991. Expression cloning and characterization of the TGF-beta type III receptor. Cell 67:797-805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Warner, B. J., S. W. Blain, J. Seoane, and J. Massague. 1999. Myc downregulation by transforming growth factor beta required for activation of the p15Ink4b G1 arrest pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:5913-5922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weijzen, S., P. Rizzo, M. Braid, R. Vaishnav, S. M. Jonkheer, A. Zlobin, B. A. Osborne, S. Gottipati, J. C. Aster, W. C. Hahn, M. Rudolf, K. Siziopikou, W. M. Kast, and L. Miele. 2002. Activation of Notch-1 signaling maintains the neoplastic phenotype in human Ras-transformed cells. Nat. Med. 8:979-986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wesley, C. S. 1999. Notch and wingless regulate expression of cuticle patterning genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:5743-5758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yagi, K., M. Furuhashi, H. Aoki, D. Goto, H. Kuwano, K. Sugamura, K. Miyazono, and M. Kato. 2002. c-myc is a downstream target of the Smad pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 277:854-861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zagouras, P., S. Stifani, C. M. Blaumueller, M. L. Carcangiu, and S. Artavanis-Tsakonas. 1995. Alterations in Notch signaling in neoplastic lesions of the human cervix. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:6414-6418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]