Abstract

Toluate dioxygenase of Pseudomonas putida mt-2 (TADOmt2) and benzoate dioxygenase of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus ADP1 (BADOADP1) catalyze the 1,2-dihydroxylation of different ranges of benzoates. The catalytic component of these enzymes is an oxygenase consisting of two subunits. To investigate the structural determinants of substrate specificity in these ring-hydroxylating dioxygenases, hybrid oxygenases consisting of the α subunit of one enzyme and the β subunit of the other were prepared, and their respective specificities were compared to those of the parent enzymes. Reconstituted BADOADP1 utilized four of the seven tested benzoates in the following order of apparent specificity: benzoate > 3-methylbenzoate > 3-chlorobenzoate > 2-methylbenzoate. This is a significantly narrower apparent specificity than for TADOmt2 (3-methylbenzoate > benzoate ∼ 3-chlorobenzoate > 4-methylbenzoate ∼ 4-chlorobenzoate ≫ 2-methylbenzoate ∼ 2-chlorobenzoate [Y. Ge, F. H. Vaillancourt, N. Y. Agar, and L. D. Eltis, J. Bacteriol. 184:4096-4103, 2002]). The apparent substrate specificity of the αBβT hybrid oxygenase for these benzoates corresponded to that of BADOADP1, the parent from which the α subunit originated. In contrast, the apparent substrate specificity of the αTβB hybrid oxygenase differed slightly from that of TADOmt2 (3-chlorobenzoate > 3-methylbenzoate > benzoate ∼ 4-methylbenzoate > 4-chlorobenzoate > 2-methylbenzoate > 2-chlorobenzoate). Moreover, the αTβB hybrid catalyzed the 1,6-dihydroxylation of 2-methylbenzoate, not the 1,2-dihydroxylation catalyzed by the TADOmt2 parent. Finally, the turnover of this ortho-substituted benzoate was much better coupled to O2 utilization in the hybrid than in the parent. Overall, these results support the notion that the α subunit harbors the principal determinants of specificity in ring-hydroxylating dioxygenases. However, they also demonstrate that the β subunit contributes significantly to the enzyme's function.

Bacterial ring-hydroxylating dioxygenases are involved in the aerobic catabolism of a wide variety of aromatic compounds and thus play a critical role in the global carbon cycle. These multicomponent enzymes catalyze the NAD(P)H-dependent dihydroxylation of the aromatic ring, incorporating both atoms of dioxygen into the product (14, 21). Ring-hydroxylating dioxygenases have applications in the biodegradation of pollutants, many of which are aromatic compounds (49). In addition, due to their regio- and enantiospecificity, these enzymes are of burgeoning importance in generating synthons for the pharmaceutical and chemical industries (7, 22).

Ring-hydroxylating dioxygenases typically consist of a hexameric oxygenase (ISP) of (αβ)3 configuration, a reductase (RED), and sometimes a ferredoxin. The α subunit of the ISP contains a Rieske-type Fe2S2 center and an active-site mononuclear iron. RED and the ferredoxin, if present, transfer reducing equivalents from NAD(P)H to the ISP. Due to their importance and potential applications, considerable effort has been focused on identifying the specificity determinants of these enzymes. Structural studies of naphthalene dioxygenase (NDO) (9) and biphenyl dioxygenase (BPDO) (12) indicate that the substrate-binding pocket is contained entirely within the C terminus of the ISP α subunit. To functionally evaluate specificity determinants, hybrid ISPs consisting of the α subunit of one enzyme and the β subunit of a related enzyme have been studied. Such experiments with NDO, BPDO, and related enzymes indicate that the α subunit is responsible for substrate preference (2, 5, 31, 40, 41). Directed mutagenesis and gene-shuffling approaches have further indicated that the α subunit harbors the principal determinants of substrate preference (3, 32, 36, 42, 43, 48). In each of these studies, enzyme function was evaluated solely in terms of substrate preference, in part due to the limited solubility of the substrates. Moreover, this preference was evaluated by using whole-cell biotransformation. Interestingly, some studies using purified hybrid ISPs indicate that the β subunit can influence the substrate preference (28, 33). This is consistent with structural data indicating that the β subunit interacts with the α subunit close to the active site of the enzyme (9, 12).

Toluate dioxygenase of Pseudomonas putida mt-2 (TADOmt2) (EC 1.14.12.-) (27) and benzoate dioxygenase of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus ADP1 (BADOADP1) (EC 1.14.12.10) are group II dioxygenases (37) (class IB according to the system of Batie et al. [4]) that catalyze the dihydroxylation of benzoates (Fig. 1). The α and β subunits of TADOmt2 are encoded by xylXY, respectively, and those of BADOADP1 are encoded by benAB, respectively (39). The RED components of TADOmt2 and BADOADP1 are encoded by xylZ and benC, respectively (25, 38). The ISP components of TADOmt2 (ISPTADO or αTβT) and BADOADP1 (ISPBADO or αBβB) share approximately 62% sequence identity yet transform different ranges of substituted benzoates. Thus, TADOmt2 transforms a wide range of substituted benzoates (54) and shows highest specificity for 3-methylbenazoate (20). In contrast, BADO transforms a much narrower range of substrates (53). The different specificities of these related enzymes and the solubility of their substrates allow kinetics studies to be performed with a wider range of substrate concentrations, thereby facilitating a more thorough investigation of the structural determinants of function in this important class of enzymes.

FIG. 1.

The reaction catalyzed by TADOmt2 and BADOADP1. These ring-hydroxylating dioxygenases initiate the catabolism of substituted benzoates, catalyzing their transformation to the corresponding cis-1,2-dihydroxycyclohexadienes. Each enzyme consists of two components: an ISP, encoded by xylXY or benAB, and a RED, encoded by xylZ or benC.

In the present study, BADOADP1 was overexpressed and purified by using approaches similar to those developed for TADOmt2. Hybrids ISPs consisting of the α subunit of one enzyme and the β subunit of the other were expressed and purified, and their respective specificities for a range of substituted benzoates were compared to those of the parent enzymes. The coupling of substrate utilization in the hybrid enzymes was also investigated. The contributions of the different subunits to the activities of these enzymes are discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

Benzoates were from Fluka Chimie. Catechols and catalase were from Sigma-Aldrich Fine Chemicals. Restriction enzymes, T4 ligase, and chromatography resins were from Amersham Biosciences. PfuI DNA polymerase was from Stratagene. Nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid Superflow resin was purchased from Qiagen. Oligonucleotides were purchased from Invitrogen Life Technologies. All other chemicals were of analytical grade. Buffers were prepared with water purified on a Barnstead (San Diego, Calif.) NANOpure UV apparatus to a resistivity of greater than 17 M × Ω · cm.

Strains and plasmids.

The strains and plasmids used in this work are listed in Table 1. Escherichia coli and P. putida strains were grown at 37 and 30°C, respectively. The medium was supplemented with 100 μg of ampicillin per ml and/or 10 μg of tetracycline per ml, as appropriate. Strains used in the propagation of DNA were grown in Luria-Bertani broth. Strains used in the expression of protein were grown in Terrific Broth (1) supplemented at 10 ml/liter with an HCl-solubilized mineral solution (20, 34, 50). One liter of medium in a 2-liter flask was inoculated with 10 ml of an overnight culture. Each of the four ISPs (αTβT, αBβB, αBβT, and αTβB) was expressed in strain P. putida CL01 containing pVLTXYZ1, pVLTAB1, pVLTAY1, and pJBXB1, respectively. When cultures reached an optical density at 600 nm of 0.6, isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside (IPTG) and 3-methylbenzoate were added to final concentrations of 0.1 and 1 mM, respectively. This amount of 3-methylbenzoate was added a second time 3 h after the initial induction. The cultures were incubated for an additional 20 h before harvesting. REDTADO and REDBADO were expressed under similar conditions by using P. putida KT2442 containing pVLTZ1 and pVLTC1, respectively. Cultures were induced with 0.5 mM IPTG and incubated for an additional 20 h before harvesting. Cell pellets were frozen at −80°C until further use.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype or propertiesa | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli DH5α | F−endA1 hsdR17 (rk− mk+) supE44 thi-1 λ−recA1 gyrA96 relA1 deoR Δ(lacZYA-argF) U169 φ80dlacZΔM15 | 23 |

| P. putida KT2442 | Prototrophic; hsdR Rif | 35 |

| P. putida CL01 | P. putida KT2442 carrying xylS; Rif Pipr | 20 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pIB1354 | pUC19 containing the benABC genes; Apr | 39 |

| pVLT31 | Broad-host-range expression vector; RSF 1010, Ptac promoter, lacIq, Tcr | 15 |

| pLEHP20 | Plac promoter, His tag expression vector, Apr | 17 |

| pEMRBS | pEMBL18 carrying Pm promoter and the phage T7 gene 10 leader sequence; Apr | F. H. Vaillancourt and L. D. Eltis, unpublished data |

| pEMBL18 | Plac promoter; Apr | 16 |

| pJB655 | Pm promoter, containing xylS; Apr | 6 |

| pEMXYZ1 | Plac promoter, pEMBL18 carrying xylXYZ; Apr | 20 |

| pEMXB1 | Plac promoter, pEMBL18 carrying xylX benB; Apr | This study |

| pEMA1 | pEMRBS carrying first part of benA; Apr | This study |

| pEMAB1 | pEMRBS carrying benAB; Apr | This study |

| pEMAY1 | pEMRBS carrying benA xylY; Apr | This study |

| pVLTXYZ1 | pVLT31 carrying xylXYZ; Tcr | 20 |

| pVLTC1 | pVLT31 carrying benC with His tag; Tcr | This study |

| pVLTZ1 | pVLT31 carrying xylZ with His tag; Tcr | 20 |

| pJBXB1 | Pm promoter; Apr carrying xyIX and benB | This study |

| pVLTAB1 | pVLT31 carrying benAB; Tcr | This study |

| pVLTAY1 | pVLT31 carrying benA and xyIY; Tcr | This study |

Apr, ampicillin resistance; Pipr, piperacillin resistance; Rif, rifampin resistance; Tcr, tetracycline resistance.

DNA manipulation.

DNA was propagated by using E. coli DH5α. DNA was purified, digested, and ligated by standard protocols (46). PCR amplification was performed with a Thermolyne model DB66P25 thermocycler (Barnstead). Oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis was performed by overlap extension PCR (47) and derivatives of pEMBL18 as the template DNA. Clones constructed by using PCR products were sequenced to verify the integrity of the sequence. Cells were transformed with plasmids via electroporation with a Gene Pulser transfection apparatus and pulse controller (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Nucleotide sequencing was performed with the ABI Dye-Deoxy terminator protocol and an ABI model 373 Stretch DNA sequencer at the Nucleic Acid Analysis Unit at Université Laval.

Construction of expression vectors.

Expression vectors for BADOADP1 and hybrid ISPs were designed based on the systems that yielded the best expression of the TADOmt2 components (20). To express αBβB, a vector was constructed by initially introducing an NcoI site at the start codon of benA in pIB1354. The initial portion of benA was then cloned as a 640-bp NcoI-HincII fragment into pEMRBS. This yielded pEMA1, in which the start codon of benA is immediately downstream of the Pm promoter and the ribosome binding site of the phage T7 gene leader sequence. The intact benA together with benB was reconstructed by inserting a 1.7-kb HincII fragment from pIB1354 into pEMA1, yielding pEMAB1. Finally, a 2.4-kb SacI-HindIII fragment containing the benAB genes together with the Pm promoter and the ribosome binding site was excised from pEMAB1 and cloned into pVLT31, yielding pVLTAB1.

To express αTβB, a BsmI site was introduced 2 bp downstream of xylX in pEMXYZ1 by directed mutagenesis with primer Bsm1XY (CTTCGTAGGAAGCATTCATTTACACGCCC [an introduced BsmI site is underlined]). A 1-kb BsmI-HincII fragment carrying benB was then excised from pIB1354 and used to replace the corresponding fragment in pEMXYZ1, yielding pEMXB1. This strategy positioned benB immediately downstream of xylX, analogous to the position of xylY in the TOL operon, without changing the sequence of XylX or BenB. Finally, a 2.5-kb XbaI-KpnI fragment from pEMXB1 containing the Pm promoter, xylX, benB, and part of benC was subcloned into pJB655 to form pJBXB1. This last cloning step took advantage of the XbaI site in the Pm promoter.

To express αBβT, xylY was amplified by PCR with primers Ay-1 (GGGAATTCGAATGCTACTATCTCCTACGAA [an introduced BsmI site is underlined]) and Ay-2 (CCCCGAAGCTTAAGTCAGTGGCAACC [an introduced HindIII site is underlined]). The resulting 500-bp fragment was digested with BsmI and HindIII and cloned into pEMAB1, yielding pEMAY1. Finally, a 2.3-kb SacI-HindIII fragment containing the benA and xylY genes together with the Pm promoter was excised from pEMAY1 and cloned into pVLT31, yielding pVLTAY1. This strategy resulted in the addition of two amino acids at the N terminus of XylY, asparagine and alanine, which are the second and third amino acids of BenB, respectively. This was done to preserve the same 4-bp overlap between benA and xylY that exists between benA and benB (26). Inspection of the sequence alignment and the structure of BPDO (12) indicates that the addition of these two amino acids to the N terminus of XylY should not change the properties of XylY.

REDBADO was expressed as a His-tagged protein by using a system analogous to that for REDTADO (20). Accordingly, benC was amplified by PCR with primers BCfor (CGCCCTGCAGTCACGACGTTG [a PstI site is underlined]) and BCrev (GCCCGCTAGCTTATATTTGAATAGG [an NheI site is underlined) from pIB1354. The resulting 1.2-kb fragment was digested with NheI and PstI and ligated into appropriately digested pLEHP20 following a sequence encoding a six-histidine tag. The His-tagged BenC encoded by this construct contains all of the residues of the wild-type protein except for the initial methionine. The gene encoding the fusion protein was then cloned into pVLT31 as an XbaI-PstI fragment, yielding pVLTC1.

Purification of proteins.

The dioxygenase components were purified anaerobically from cell pellets essentially as previously described for the TADOmt2 components (20). Accordingly, the wild-type and hybrid ISPs were purified by using anion-exchange, gel filtration, and hydrophobic interaction chromatographies. The His-tagged REDs (ht-REDs) were purified by using immobilized metal affinity chromatography. Anaerobically prepared buffers used in the purification of ISPs contained 10% glycerol, 0.25 mM Fe(NH4)2(SO4)2, and 2 mM dithiothreitol to maximize the specific activity of the preparation. Protein-containing fractions were concentrated by ultrafiltration with an Amicon stirred cell equipped with a YM10 filter (Millipore, Nepean, Ontario, Canada). Preparations of purified protein were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen as beads and stored at −80°C until further use. Protein stored in this manner exhibited no loss of activity over 6 months.

Determination of protein purity and concentration.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis was performed on a Bio-Rad Mini-Protean II apparatus with Coomassie blue staining according to established procedures (1). Protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford method (8) with bovine serum albumin as a standard. ISP concentrations were calculated by using the extinction coefficients presented in Results.

Determination of iron and sulfur contents.

Iron and sulfur concentrations were determined colorimetrically with Ferene S (24) and N,N-dimethyl-p-phenylene-diamine (11), respectively. Samples were manipulated in gas-tight cuvettes. All assays were performed in duplicate. The correlation coefficients of the standard curves were at least 0.98.

Steady-state kinetic studies.

The dioxygenase-catalyzed reactions were monitored polarographically following the consumption of O2 by using a Clarke-type oxygen electrode (model 5301; Yellow Springs Instruments, Yellow Springs, Ohio), a thermojacketed respiration chamber, an O2 meter, and a microcomputer as described previously (20, 50). The full scale was established by using buffer equilibrated with 5, 20, 50, or 100% O2 (see below), depending on the experiment. The oxygen electrode was zeroed and calibrated as described previously (20). Initial velocities were determined from progress curves by analyzing the data with Microsoft Excel.

The standard activity assay was performed in a total volume of 1.4 ml of air-saturated 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0; 25 ± 1°C) (∼290 μM dissolved O2) containing 430 μM NADH and either 100 μM 3-methylbenzoate (for TADOmt2) or 100 μM benzoate (for BADOADP1). RED was added to a final concentration of 2.0 μM, and the background was recorded. The reaction was initiated by injecting the appropriate ISP into the reaction chamber to a final concentration of 0.37 μM. One unit of enzymatic activity was defined as the quantity of enzyme required to consume 1 μmol of O2/min.

Reaction buffers containing different concentrations of dissolved O2 were prepared by using humidified mixtures of O2 and N2 gases and were transferred to the gas-flushed reaction chamber by using a gas-tight syringe as described previously (20, 50).

Analysis of steady-state data.

Steady-state kinetic data were analyzed by using an equation that describes a compulsory-order ternary-complex mechanism (13) in which the binding of the aromatic substrate, A, precedes that of O2:

|

In this equation, KmA represents the Km for the aromatic substrate,  represents the Km for O2, and KdA represents the dissociation constant for the aromatic substrate. The steady-state kinetic parameters were evaluated by using the program LEONORA (13). They are apparent, as they depend on the concentration of RED (20).

represents the Km for O2, and KdA represents the dissociation constant for the aromatic substrate. The steady-state kinetic parameters were evaluated by using the program LEONORA (13). They are apparent, as they depend on the concentration of RED (20).

Coupling measurements.

Coupling experiments for all substrates were carried out under the same conditions as for the standard activity assay except that the RED, ISP, and substrate concentrations were 4, 1.8, and 215 μM, respectively. Reactions were initiated by adding ISP and quenched by diluting 200 μl of the reaction mixture with 400 μl of methanol 3 min after the initiation of the reaction or when O2 consumption stopped. Oxygen consumption was monitored with the O2 electrode. The consumption of aromatic substrate was determined by HPLC measurements. The amount of substrate remaining was determined from the area of the absorbance peak at 280 nm at the respective retention time. Standard curves were obtained from treating the pure substituted-benzoate solution in the same way as reaction mixtures at different known concentrations. The amount of hydrogen peroxide was determined by measuring the amount of O2 released upon the addition of catalase as described previously (20).

Identification of reaction products.

The products of dioxygenase-catalyzed reactions were identified in reactions performed and quenched as described for the coupling assay except that the reaction mixture also contained 1.2 μM XylL and 128 μM NAD+ to transform cis-diols to the corresponding catechol. Substituted catechols were identified in reaction mixtures by comparing the retention times and absorption spectra of HPLC peaks with those for commercially available catechols. In some instances, product identification was confirmed by further treating reaction mixtures with catechol 2,3-dioxygenase and comparing the absorption spectra of the cleavage products with those of known compounds.

HPLC measurements.

HPLC measurements were performed with a Millennium32 system (Waters Corporation, Milford, Mass.), including a Waters 2996 photodiode array detector and an Alliance Waters 2695 separations module equipped with a C18 reverse-phase octyldecyl silane hypersil column (4 by 125 mm). All components were interfaced with a Milliennium32 Client/Server. Samples of 10 μl were injected, and the column was operated at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. Benzoates, cis-diols, and catechols were resolved by using a 4:1 (vol/vol) mixture of 0.3% H3PO4 and acetonitrile, a 9:1 (vol/vol) mixture of H2O and acetonitrile, and an 4:1 (vol/vol) mixture of H2O and acetonitrile, respectively.

UV-visible absorption spectroscopy.

Absorption spectra were recorded with a Varian Cary 1E spectrophotometer equipped with a thermojacketed cuvette holder maintained at 25°C. The spectrophotometer was interfaced to a microcomputer and controlled by Cary WinUV software (version 2.00). Samples contained 1.2 μM protein in 25 mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.3. Spectra of anaerobic samples were recorded with a 3-ml gas-tight cuvette (Hellma, Concord, Ontario, Canada). Oxidized samples were prepared in a glove box by adding several grains of K3Fe(CN)6 to the protein sample and passing the sample through a small desalting column (0.7 by 6 cm; Bio-Gel P6 DG) equilibrated with the buffer of choice.

RESULTS

Expression and purification.

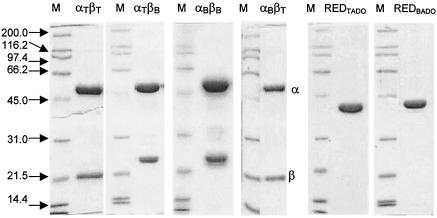

Wild-type and hybrid ISPs were expressed at relatively high levels in P. putida CL01 by using the constructs and protocols described in Material and Methods; each ISP constituted more than 20% of the total cellular protein (results not shown). Approximately 32 to 100 mg of each ISP was purified from 24 g (wet weight) of cells (Table 2). The final preparation of each ISP was judged to be greater than 90% pure based on a Coomassie blue-stained denaturing gel (Fig. 2). Elution of αBβB and hybrid ISPs from the gel filtration column was consistent with each ISP having a molecular mass of approximately 215 kDa (20).

TABLE 2.

Purification of ISPs

| ISP | Protein yield (mg) | Sp act (U/mg)a | Fe content (Fe/α3β3) | S content (S/α3β3) |

A280/A323

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidized | Reduced | |||||

| αBβB | 75 | 5.0 | 11 | 6.0 | 6.1 | 12.7 |

| αTβT | 39 | 3.8 | 16 | 5.8 | 4.5 | 6.7 |

| αTβB | 100 | 2.3 | 15 | 5.9 | 4.5 | 6.7 |

| αBβT | 32 | 3.1 | 12 | 5.9 | 6.1 | 12.7 |

Activity units are defined in Materials and Methods. Specific activities were obtained with 3-methylbenzoate for αTβT and αTβB and with benzoate for αBβB and αBβT.

FIG. 2.

Denaturing gels of purified preparations of TADOmt2 and BADOADP1 components. The first four gels were loaded with molecular weight standards (lanes M) and 5 μg of the indicated wild-type or hybrid ISP preparation. The α and β subunits are indicated. The last two gels were loaded with molecular weight standards and 5 μg of indicated RED preparation.

REDBADO was expressed as a His-tagged protein in P. putida KT2442 at a level similar to that reported for ht-REDTADO (20). ht-REDBADO was purified anaerobically in a single step by using immobilized metal affinity chromatography as described for ht-REDTADO, thereby preventing loss of the flavin adenine dinucleotide (20). Approximately 60 mg of ht-REDBADO was purified to greater than 99% apparent homogeneity from 4 liters of culture (Fig. 2). The His tag was not removed, as previous studies with REDTADO indicated that its presence did not influence dioxygenase activity.

Characterization of metallocenters.

The iron and sulfur contents of purified ISPs were determined with anaerobically desalted samples of protein. The values indicate that each ISP contained full complements of FeS and mononuclear iron prosthetic groups (Table 2). While all ISPs seemed to contain adventitiously bound iron, ISPs containing the α subunit of TADOmt2 (αTβT and αTβB) contained more.

The UV-visible spectra of αBβB, αTβB, and αBβT were similar to that of αTβT (20), absorbing maximally at 280, 323, and 455 nm. As observed for αTβT (20), the anaerobic addition of sodium hydrosulfite to preparations of these ISPs as purified did not affect their spectra. This indicates that as purified, the Rieske-type FeS cluster of each ISP was fully reduced. As reported for αTβT, the FeS cluster could be oxidized in samples of each ISP by either exposure to air for 20 min or treatment with a slight excess of K3Fe(CN)6 (results not shown). The R value (A280/A323) of each oxidized ISP is lower than that of the corresponding reduced form (Table 2), principally because the absorption bands of the oxidized cluster are more intense than those of the reduced cluster. Interestingly, the R value of purified αTβT was significantly lower than that of αBβB (Table 2). Similarly, preparations of purified αTβT had a more intense brown color than preparations of αBβB of similar concentration. Indeed, the extinction coefficients of reduced αTβT and αBβB at 323 nm were 83.42 and 40.55 cm−1 mM−1, respectively (25 mM HEPES buffer [pH 7.3], 10% glycerol, 25°C), based on the sulfur content of the ISP. These values are comparable to those reported for oxidized 2-halobenzoate 1,2-dioxygenase (34 cm−1 mM−1) (18) and for BADOC1 from Pseudomonas arvilla C-1 (58.6 cm−1 mM−1) (53) based on protein concentration. However, the absorption of the oxidized ISP is generally 50% higher than that of the reduced protein, indicating that the present preparations of αTβT and αBβB probably contain a higher proportion of their Fe2S2 cluster. Finally, the R value of each hybrid ISP corresponded to that of the parent from which the α subunit originated. This is consistent with structural data showing that the Fe2S2 cluster in ring-hydroxylating dioxygenases is contained entirely with the α subunit (30).

The stabilities of the wild-type and hybrid ISPs were compared by monitoring the absorption at 455 nm (A455) of oxidized samples incubated at room temperature. After 48 h, the A455 of aerobic, oxidized samples of αTβT, αTβB, αBβB, and αBβT decreased by 6, 12, 26, and 58%, respectively. These data indicate that exchanging the β subunit decreased the stability of the ISP with respect to that of the parent enzyme from which the α subunit originated. However, the change in A455 was insignificant over the time course of a kinetic experiment. Finally, anaerobically incubated ISP samples were approximately five times more stable than the aerobic samples (data not shown).

Anaerobically purified preparations of ht-REDBADO and ht-REDTADO each absorbed maximally at 270, 340, and 455 nm and had essentially identical R values (A270/A455) of 3.1. Exposure of samples of RED to air resulted in an increase of the R value to a maximum of 5.9, which was observed at 20 min. Oxidized samples of RED could be reduced with a small molar excess of NADH (results not shown).

In vitro reconstitution of dioxygenase activity.

Dioxygenase activity was reconstituted in vitro under the standard conditions described for TADOmt2 (molar ratio of RED to ISP of approximately 5.4:1, 0.1 M ionic strength phosphate buffer [pH 7.0], 25°C) and monitored by using an oxygraph assay (20). The specific activity of each reconstituted dioxygenase was determined by using the derivative of benzoate for which it showed the highest apparent specificity (i.e., 3-methylbenzoate for αTβT and αTβB and benzoate for αBβB and αBβT [see below]) and by using the RED of the dioxygenase from which the α subunit originated (i.e., ht-REDTADO for αTβT and αTβB and ht-REDBADO for αBβB and αBβT). Under these conditions, the specific activities of the dioxygenases reconstituted with αTβT, αBβB, αTβB, and αBβT were 3.8, 5.0, 2.3, and 3.1 U/mg, respectively.

Steady-state kinetics.

Steady-state kinetics studies were performed with a variety of substituted benzoates to determine the apparent specificities of wild-type and hybrid dioxygenases.

BADOADP1 had a narrower specificity than TADOmt2, transforming only four of seven selected substrates (Table 3). The best substrate for BADOADP1 was benzoate (KmA = 26 ± 1 μM, kcat = 8.6 ± 0.1 s−1, and  = 53 ± 2 μM), and the enzyme utilized substituted benzoates in the following order of apparent specificity: benzoate > 3-methylbenzoate > 3-chlorobenzoate > 2-methylbenzoate. In contrast, TADOmt2 utilized substituted benzoates in the following order of apparent specificity: 3-methylbenzoate > benzoate ∼ 3-chlorobenzoate > 4-methylbenzoate ∼ 4-chlorobenzoate ≫ 2-methylbenzoate ∼ 2-chlorobenzoate (20). Thus, BADOADP1 and TADOmt2 differed significantly in their abilities to utilize para-substituted benzoates.

= 53 ± 2 μM), and the enzyme utilized substituted benzoates in the following order of apparent specificity: benzoate > 3-methylbenzoate > 3-chlorobenzoate > 2-methylbenzoate. In contrast, TADOmt2 utilized substituted benzoates in the following order of apparent specificity: 3-methylbenzoate > benzoate ∼ 3-chlorobenzoate > 4-methylbenzoate ∼ 4-chlorobenzoate ≫ 2-methylbenzoate ∼ 2-chlorobenzoate (20). Thus, BADOADP1 and TADOmt2 differed significantly in their abilities to utilize para-substituted benzoates.

TABLE 3.

Apparent steady-state kinetic parameters of ISPs for selected substituted benzoatesa

| ISP | Substrate | KmA (μM) | KmO2 μM | kcat (s−1) | kcat/KmA (104 M−1 s−1) | kcat/KmO2 (104 M−1 s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| αBβB | Benzoate | 26 (1) | 53 (2) | 8.6 (0.1) | 33 (3) | 16 (1) |

| 2-Methylbenzoate | 1,401 (48) | 247 (20) | 4.2 (0.2) | 0.3 (0.1) | 1.7 (0.9) | |

| 3-Methylbenzoate | 89 (6) | 129 (11) | 7.0 (0.5) | 8 (2) | 5.4 (0.4) | |

| 3-Chlorobenzoate | 113 (8) | 128 (11) | 3.0 (0.1) | 3 (1) | 2.3 (0.5) | |

| αTβTc | Benzoate | 19 (4) | 13 (2) | 2.8 (0.1) | 15 (3) | 22 (2) |

| 2-Methylbenzoate | 250 (65) | 46 (10) | 2.3 (0.13)b | 0.9 (0.2)b | 4.9 (0.9) | |

| 3-Methylbenzoate | 9.1 (1.3) | 16 (2) | 3.9 (0.2) | 43 (4) | 25 (2) | |

| 4-Methylbenzoate | 28 (6) | 8.4 (1.5) | 2.5 (0.1) | 9 (2) | 30 (4) | |

| 2-Chlorobenzoate | 144 (90) | 92 (22) | 1.9 (0.1)b | 13 (0.8)b | 2.1 (0.4) | |

| 3-Chlorobenzoate | 26 (3) | 19 (6) | 3.1 (0.1) | 15 (1) | 21 (1) | |

| 4-Chlorobenzoate | 41 (9) | 12 (2) | 3.0 (0.1) | 8 (1) | 25 (3) |

Experiments were performed with 0.1 M sodium phosphate (pH 7.0 at 25°C) containing 430 μM NADH. Standard errors are given in parentheses. ht-REDs were paired with the α subunit of the ISP. The data sets used to calculate the parameters for different substrates contain 80 to 110 points. BADO displayed no detectable activity in the presence of either 4-methylbenzoate, 2-chlorobenzoate, or 4-chlorobenzoate.

Values were based on O2 consumption to be consistent with the other values in the table. Values calculated based on benzoate consumption were at least one order of magnitude lower.

Values published in reference 20.

The nature of the substituted benzoate influenced the ability of BADOADP1 to utilize O2 (Table 3). This was also observed for TADOmt2 (20). However, in the case of BADOADP1, the  correlates with the specificity of the enzyme for the substituted benzoate. Thus, the

correlates with the specificity of the enzyme for the substituted benzoate. Thus, the  of BADOADP1 was lowest in the presence of benzoate (the enzyme's preferred substrate), was 2 times higher in the presence of 3-methylbenzoate and 3-chlorobenzoate, and was highest in the presence of 2-methylbenzoate (the worst substrate tested).

of BADOADP1 was lowest in the presence of benzoate (the enzyme's preferred substrate), was 2 times higher in the presence of 3-methylbenzoate and 3-chlorobenzoate, and was highest in the presence of 2-methylbenzoate (the worst substrate tested).

The apparent steady-state kinetic parameters of a given wild-type ISP were relatively unaffected when the dioxygenase was reconstituted with each of the two ht-REDs. Thus, the specific activities of αTβT and αBβB were both slightly higher in the presence of ht-REDTADO (Table 4), and small differences in the apparent kcat and Km were observed. However, the apparent specificity of each ISP for 3-methylbenzoate and benzoate was unaffected by the identity of RED (results not shown). As noted in studies with TADOmt2, the level of RED affects both the Km and the kcat (20). Subsequent experiments with hybrid ISPs were performed with the RED of the dioxygenase from which the α subunit originated. This choice was guided in part by the observation that the α subunit of toluene dioxygenase could be reduced in the absence of the β subunit with NADH and catalytic amounts of this enzyme's RED and ferredoxin (29).

TABLE 4.

Activities of ISPs with different reductasesa

| ISP | RED | Substrate | Sp act (U/mg)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| αBβB | TADOmt2 | Benzoate | 14.5 (0.8) |

| 3-Methylbenzoate | 10.2 (0.9) | ||

| BADOADP1 | Benzoate | 8.2 (0.4) | |

| 3-Methylbenzoate | 7.6 (0.3) | ||

| αTβT | TADOmt2 | Benzoate | 3.0 (0.2) |

| 3-Methylbenzoate | 3.2 (0.1) | ||

| BADOADP1 | Benzoate | 1.7 (0.1) | |

| 3-Methylbenzoate | 2.8 (0.2) |

Experiments were performed with 100 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.0, 25°C) containing 430 μM NADH.

Standard errors are in parentheses.

The apparent substrate specificities of αTβB and αBβT for substituted benzoates were determined in air-saturated buffer (Table 5). The apparent substrate specificity of αBβT corresponded to that of BADOADP1, the parent from which the α subunit originated. In contrast, αTβB differed slightly from TADOmt2 in that it had greatest apparent specificity for 3-chlorobenzoate (3-chlorobenzoate > 3-methylbenzoate > benzoate ∼ 4-methylbenzoate > 4-chlorobenzoate > 2-methylbenzoate > 2-chlorobenzoate). In general, the KmA of each hybrid ISP for a given benzoate was 2- to 10-fold higher than that of the corresponding parent ISP.

TABLE 5.

Apparent steady-state kinetic parameters of ISPs for selected substituted benzoates in air-saturated buffer

| ISP | Substrate | KmA (μM) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/KmA (104 M−1 s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| αBβB | Benzoate | 38 (1) | 16.3 (0.3) | 43 (1) |

| 2-Methylbenzoate | 2,890 (240) | 2.1 (0.2) | 0.07 (0.01) | |

| 3-Methylbenzoate | 49 (3) | 5.3 (0.2) | 11 (2) | |

| 3-Chlorobenzoate | 94 (8) | 2.2 (0.1) | 2.3 (0.3) | |

| αTβTc | Benzoate | 15 (1) | 2.4 (0.1) | 16 (1) |

| 2-Methylbenzoate | 590 (60) | 1.6 (0.1)b | 0.3 (0.02)b | |

| 3-Methylbenzoate | 5.3 (0.3) | 2.9 (0.04) | 46 (3) | |

| 4-Methylbenzoate | 43 (3) | 2.25 (0.06) | 5 (1) | |

| 2-Chlorobenzoate | 1,200 (240) | 1.4 (0.1)b | 0.1 (0.01)b | |

| 3-Chlorobenzoate | 22 (2) | 1.03 (0.01) | 4.6 (0.5) | |

| 4-Chlorobenzoate | 83 (7) | 0.86 (0.03) | 1 (0.1) | |

| αTβB | Benzoate | 81 (7) | 1.3 (0.12) | 1.6 (0.1) |

| 2-Methylbenzoate | 410 (124) | 0.3 (0.02) | 0.09 (0.01) | |

| 3-Methylbenzoate | 38 (4) | 1.4 (0.06) | 3.6 (0.2) | |

| 4-Methylbenzoate | 73 (1) | 1.2 (0.16) | 1.7 (0.2) | |

| 2-Chlorobenzoate | 1,200 (22) | 0.3 (0.02) | 0.02 (0.005) | |

| 3-Chlorobenzoate | 20 (3) | 1.3 (0.05) | 7 (1) | |

| 4-Chlorobenzoate | 458 (96) | 1.47 (0.09) | 0.3 (0.06) | |

| αBβT | Benzoate | 110 (20) | 4.0 (0.2) | 3.6 (0.3) |

| 2-Methylbenzoate | 5,130 (390) | 2.7 (0.2) | 0.05 (0.01) | |

| 3-Methylbenzoate | 178 (2) | 2.4 (0.3) | 1.3 (0.1) | |

| 3-Chlorobenzoate | 281 (38) | 3.1 (0.1) | 1.1 (0.1) |

Experiments were performed with 0.1 M air-saturated sodium phosphate (pH 7.0 at 25°C) containing 430 μM NADH. Standard errors are given in parentheses. ht-REDs were paired with the α subunit of the ISP. In these assays, αBβB and αBβT displayed no detectable activity in the presence of p-toluate, 2-chlorobenzoate, or 4-chlorobenzoate.

Values were based on O2 consumption to be consistent with the other values in the table. Values calculated based on benzoate consumption were at least one order of magnitude lower.

Values published in reference 20.

Coupling of O2 consumption to benzoate transformation.

In BADOADP1, substrate and O2 consumption were well coupled for all benzoates used in this study (Table 6). This is in contrast to TADOmt2, in which the utilization of ortho-substituted benzoates was very poorly coupled to O2 consumption (20). Benzoate turnover was as well coupled to O2 utilization in the αBβT hybrid, as in BADOADP1. Unexpectedly, the turnover of ortho-substituted benzoates was much better coupled to O2 utilization in the αTβB hybrid than in TADOmt2.

TABLE 6.

Coupling of substrate utilization in TADOmt2, BADOADP1, and their hybridsa

| Enzyme | Substrate | Substrate/O2 ratio | H2O2/O2 ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| αBβB | Benzoate | 1.02 (0.08) | 0.01 (0.002) |

| 2-Methylbenzoate | 1.01 (0.10) | 0.04 (0.01) | |

| 3-Methylbenzoate | 1.04 (0.12) | 0.02 (0.002) | |

| 3-Chlorobenzoate | 1.04 (0.10) | 0.002 (0.0008) | |

| αTβTb | Benzoate | 0.96 (0.10) | 0.03 (0.006) |

| 2-Methylbenzoate | 0.10 (0.10) | 0.27 (0.02) | |

| 3-Methylbenzoate | 0.92 (0.13) | 0.01 (0.003) | |

| 4-Methylbenzoate | 0.90 (0.10) | 0.03 (0.005) | |

| 2-Chlorobenzoate | 0.10 (0.09) | 0.2 (0.05) | |

| 3-Chlorobenzoate | 0.94 (0.10) | 0.002 (0.0005) | |

| 4-Chlorobenzoate | 0.93 (0.10) | 0.03 (0.01) | |

| αTβB | Benzoate | 0.98 (0.10) | 0.02 (0.003) |

| 2-Methylbenzoate | 0.92 (0.10) | 0.04 (0.002) | |

| 3-Methylbenzoate | 0.98 (0.13) | 0.007 (0.001) | |

| 4-Methylbenzoate | 0.94 (0.10) | 0.01 (0.003) | |

| 2-Chlorobenzoate | 0.90 (0.09) | 0.05 (0.01) | |

| 3-Chlorobenzoate | 0.96 (0.10) | 0.03 (0.0006) | |

| 4-Chlorobenzoate | 0.97 (0.10) | 0.04 (0.007) | |

| αBβT | Benzoate | 1.02 (0.10) | 0.03 (0.003) |

| 2-Methylbenzoate | 1.01 (0.10) | 0.02 (0.02) | |

| 3-Methylbenzoate | 1.04 (0.13) | 0.01 (0.002) | |

| 3-Chlorobenzoate | 1.01 (0.10) | 0.02 (0.0003) |

Experiments were performed with air-saturated 100 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.0 at 25°C) containing 430 μM NADH, 4 μM RED, 1.8 μM ISP, and 215 μM substrate. Standard errors are given in parentheses. The reductase in the assay was paired to the α subunit of the ISP.

Values published in reference 20.

Identification of reaction products.

A single reaction product was detected for each substrate turned over by BADOADP1, as observed for the TADOmt2-catalyzed transformations (20). For benzoate and 3-methylbenzoate, these products eluted at 2.152 and 2.168 min, respectively, and absorbed maximally at 261.5 and 262.7 nm, respectively. When treated with XylL, the resultant compounds coeluted with catechol and 3-methylcatechol, respectively, in HPLC analyses, and the amount of catechol detected corresponded to the amount of benzoate transformed within experimental error. In the case of 2-methylbenzoate, the cis-diol coeluted with the cis-diol produced from benzoate and had the same absorption as the latter, again as observed for TADOmt2. These results indicate that both TADOmt2 and BADOADP1 exclusively catalyzed the 1,2-dihydroxylation of the tested benzoates.

In general, the hybrid ISPs transformed benzoates to the same products as the parental enzymes. The αTβB hybrid proved to be exceptional, as it transformed 2-methylbenzoate to a product whose retention time on the HPLC column (2.036 min) and absorption spectrum (λmax = 262.7 min) did not correspond to those of any of the other cis-diols observed in this study, including that produced from 2-methylbenzoate by TADOmt2 and BADOADP1. Transformation of this unknown cis-diol by XylL and catechol 2,3-dioxygenase yielded a yellow product whose spectrum was identical to that of the meta-cleavage product of 3-methylcatechol. TADOmt2 transforms 3-methylbenzoate to 1,2-dihydroxy-3-methyl-cyclohexa-3,5-diene-carboxylate, which is also transformed to 3-methylcatechol (20). However, the cis-diol produced by the αTβB-catalyzed transformation of 2-methylbenzoate was clearly different. It was therefore concluded that the latter was 1,6-dihydroxy-2-methyl-cyclohexa-2,4-diene-carboxylate.

DISCUSSION

TADOmt2 and BADOADP1 are group II aromatic ring-hydroxylating dioxygenases whose ISP and RED components share 62 and 53% sequence identity, respectively (26). Their relatively high degree of similarity and the solubility of their respective substrates make these enzymes a useful model for studies of specificity determinants in ring-hydroxylating dioxygenases. Since BADOs from different bacterial isolates have been characterized to different extents in the literature and since no specificity data exist for any of these, it was first necessary to determine the reactivity of BADOADP1 with substituted benzoates.

The activity of purified, reconstituted BADOADP1 reported here is consistent with that of BADOC1, whose substrate preference was investigated by using 1 mM concentrations of different benzoates (benzoate > 3-methylbenzoate > 3-chlorobenzoate > 2-methylbenzoate) (53). Thus, BADOs from both strains have a preference for methyl versus chloro substituents and for substituents in the following positions: meta > ortho > para. BADOB13, present in 3-chlorobenzoate-grown Pseudomonas sp. strain B-13, has this same preference for substituent position (44). However, the B-13 enzyme prefers chloro substituents over methyl substituents. The substrate preference of 2-halobenzoate 1,2-dioxygenase of Pseudomonas cepacia 2CBS, which shares 56% sequence identity with BADOADP1, is different again, preferentially utilizing chloro versus methyl substituents and benzoates substituted in the following positions: ortho > meta > para (18). Significant for the present study, the apparent substrate specificity of BADOADP1 was narrower than that of TADOmt2 (20) and differed in its preference of ortho versus para substituted benzoates.

The relative interchangeability of REDTADO and REDBADO in the two dioxygenases is not surprising given their sequence identity. Single-turnover studies have established that the reductase component is required for product release from the ISP but not for substrate hydroxylation (51, 52). Indeed, some ring-hydroxylating enzymes appear to share the same reductase in vivo. Thus, in Ralstonia sp. strain U2, the respective ISPs of salicylate 5-hydroxylase, which transforms salicylate to gentisate, and NDO share a ferredoxin and reductase (55). Similarly, plasmid pNL1 of Sphingomonas aromaticivorans F199 carries genes encoding seven different ISPs but only two copies of reductase-encoding genes (45), although it is possible that other reductases are encoded elsewhere in the genome.

The apparent specificity of each of the hybrid enzymes, αTβB and αBβT, corresponded most closely to that of the parent from which the α subunit originated. This indicates that this subunit harbors the major determinants of specificity in these group II dioxygenases. This finding is consistent with the results of subunit-swapping experiments with group III and IV enzymes, including NDO (40, 41) and BPDO (2, 31). Directed mutagenesis and gene-shuffling experiments with these systems have further localized the major determinants of substrate preference in the group III and IV enzymes to the C-terminal domain of the α subunit (3, 32, 36, 42, 43, 48). The present study extends this finding, as it investigates substrate specificity in purified enzymes.

The present study nevertheless clearly indicates that the β subunit contributes to reactivity of the dioxygenase. Thus, although αTβB transformed the same broad range of substituted benzoates as TADOmt2, the apparent specificities of these ISPs were slightly different despite the ISPs sharing the same α subunit. Moreover, αTβB transformed 2-methylbenzoate with a different regioselectivity and improved coupling compared to αTβT. The contribution of the β subunit to dioxygenase reactivity has been suggested in at least two studies of hybrid BPDOs. For example, replacement of the β subunit of toluene dioxygenase with that of a BPDO yielded an enzyme with improved trichloroethylene-transforming activity (19, 33). Similarly, the ability of purified hybrid BPDOs to transform polychlorinated biphenyls was determined to some extent by the β subunit (10, 28). Interestingly, the present studies are consistent with an early insertional mutagenesis study of TADO that demonstrated that disruption of the β subunit affects the enzyme's substrate preference (27).

The observation that the β subunit contributes to the reactivity of ring-hydroxylating dioxygenases is consistent with crystallographic structures of NDO (9) and BPDO (12). These structures demonstrate that while the mononuclear Fe(II) site and the substrate-binding pocket of the ISP are contained entirely within the C-terminal domains of the α subunits of these enzymes, the β subunit probably contributes to the structural integrity and function of the active site. Thus, in BPDO, the interface between the α and β subunits is extensive, constituting a buried surface of 3,360 Å2 per αβ dimer. Much of this interface involves a central sheet of the β subunit and an extended helix of the α subunit. This extended helix contains Asp386, one of the Fe(II) ligands. Similar packing interactions in NDO lock the structurally analogous helix of this dioxygenase in position. Moreover, the structure of the BPDO-product complex suggests that the extended helix shifts by up to 1.4 Å during the catalytic cycle of the enzyme (C. L. Colbert and J. T. Bolin, personal communication). Thus, the structural data indicate that the close contacts between the α and β subunits in the vicinity of the active site could influence substrate specificity, the coupling of substrate utilization during the dynamic catalytic process, and the stability of the ISP.

The present study demonstrates the value of using highly active, purified enzyme preparations in investigating the structural determinants of substrate specificity. More specifically, the results demonstrate that it will be important not to overlook the role of the β subunit in generating ring-hydroxylating dioxygenases with useful activities, both to fine-tune these activities and to optimize the stability of variant enzymes (3, 42, 43, 48). Indeed, it is possible that subunit exchange occurred during the natural evolution of ring-hydroxylating dioxygenases to produce enzymes with novel, useful activities. Current efforts are being focused on understanding the structural basis of the specificities of different BADOs for chlorinated versus alkylated benzoates.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada operating grant 171359-99 to L.D.E.

We thank Frédéric H. Vaillancourt for critically reading the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kinston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl. 2000. Current protocols in molecular biology. J. Wiley & Sons Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 2.Barriault, D., C. Simard, H. Chatel, and M. Sylvestre. 2001. Characterization of hybrid biphenyl dioxygenases obtained by recombining Burkholderia sp. strain LB400 bphA with the homologous gene of Comamonas testosteroni B-356. Can. J. Microbiol. 47:1025-1032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barriault, D., M.-M. Plante, and M. Sylvestre. 2002. Family shuffling of a targeted bphA region to engineer biphenyl dioxygenase. J. Bacteriol. 184:3794-3800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Batie, C. J., D. P. Ballou, and C. C. Correll. 1991. Phthalate dioxygenase reductase and related flavin-iron-sulfur containing electron transferases. Chem. Biochem. Flavoenzymes 3:543-556. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beil, S., J. R. Mason, K. N. Timmis, and D. H. Pieper. 1998. Identification of chlorobenzene dioxygenase sequence elements involved in dechlorination of 1,2,4,5-tetrachlorobenzene. J. Bacteriol. 180:5520-5528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blatny, J. M., T. Brautaset, H. C. Winther-Larsen, P. Karunakaran, and S. Valla. 1997. Improved broad-host-range RK2 vectors useful for high and low regulated gene expression levels in gram-negative bacteria. Plasmid 38:35-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyd, D. R., and G. N. Sheldrake. 1998. The dioxygenase-catalysed formation of vicinal cis-diols. Nat. Prod. Rep. 15:309-3224. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carredano, E., A Karlsson, B. Kauppi, D. Choudhury, R. E. Parales, J. V. Parales, K. Lee, D. T. Gibson, H. Eklund, and S. Ramaswamy. 2000. Substrate binding site of naphthalene 1,2-dioxygenase: functional implications of indole binding. J. Mol. Biol. 296:701-712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chebrou, H., Y. Hurtubise, D. Barriault, and M. Sylvesstre. 1999. Heterologous expression and characterization of the purified oxygenase and of chimeras derived from it. J. Bacteriol. 181:4805-4811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen, J. S., and L. E. Mortenson. 1977. Inhibition of methylene blue formation during determination of the acid-labile sulphide of iron-sulphur protein samples containing dithionite. Anal. Biochem. 79:157-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colbert, C. L. 2000. Ph.D. thesis. Purdue University, West Lafayette, Ind.

- 13.Cornish-Bowden, A. 1995. Analysis of enzyme kinetic data. Oxford University Press, New York, N.Y.

- 14.Dagley, S. 1978. Determinants of biodegradability. Q. Rev. Biophys. 11:577-602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Lorenzo, V., L. D. Eltis, B. Kessler, and K. N. Timmis. 1993. Analysis of Pseudomonas gene products using lacIq/Ptrp-lac plasmids and transposons that confer conditional phenotypes. Gene 123:17-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dente, L., and R. Cortese. 1987. pEMBL: a new family of single-stranded plasmids for sequencing DNA. Methods Enzymol. 155:111-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eltis, L. D., S. Iwagami, and M. Smith. 1994. Hyperexpression of a synthetic gene encoding a high potential iron sulfur protein. Protein Eng. 7:1145-1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fetzner, S., R. Muller, and F. Lingens. 1992. Purification and some properties of 2-halobenzoate 1,2-dioxygenase, a two-component enzyme system from Pseudomonas cepacia 2CBS. J. Bacteriol. 174:279-290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Furukawa, K., J. Hirose, S. Hayashida, and K. Nakamura. 1994. Efficient degradation of trichloroethylene by a hybrid aromatic ring dioxygenase. J. Bacteriol. 176:2121-2123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ge, Y., F. H. Vaillancourt, N. Y. Agar, and L. D. Eltis. 2002. Reactivity of toluate dioxygenase with substituted benzoates and dioxygen. J. Bacteriol. 184:4096-4103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gibson, D. T. 1987. Microbial metabolism of aromatic hydrocarbons and the carbon cycle, p. 33-58. In S. R. Hagedorn, R. S. Hanson, and D. A. Kunz (ed.), Microbial metabolism and the carbon cycle. Horwood Academic Press, Chur, Switzerland.

- 22.Gibson, D. T., and R. E. Parales. 2000. Aromatic hydrocarbon dioxygenases in environmental biotechnology. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 11:236-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grant, S. G. N., J. Jessee, F. R. Bloom, and D. Hanahan. 1990. Differential plasmid rescue from transgenic mouse DNAs into Escherichia coli methylation-restriction mutants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:4645-4649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haigler, B. E., and D. T. Gibson. 1990. Purification and properties of NADH-ferredoxinNAP reductase, a component of naphthalene dioxygenase from Pseudomonas sp. strain NCIB 9816. J. Bacteriol. 172:457-464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harayama, S., and M. Rekik. 1990. The meta cleavage operon of TOL degradative plasmid pWW0 comprises 13 genes. Mol. Gen. Genet. 221:113-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harayama, S., M. Rekik, A. Bairoch, E. L. Neidle, and L. N. Ornston. 1991. Potential DNA slippage structures acquired during evolutionary divergence of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus chromosomal benABC and Pseudomonas putida TOL pWW0 plasmid xylXYZ, genes encoding benzoate dioxygenases. J. Bacteriol. 173:75407548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harayama, S., M. Rekik, and K. N. Timmis. 1986. Genetic analysis of a relaxed substrate specificity aromatic ring dioxygenase, toluate 1,2-dioxygenase, encoded by TOL plasmid pWW0 of Pseudomonas putida. Mol. Gen. Genet. 202:226-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hurtubise, Y., D. Barriault, and M. Sylvestre. 1998. Involvement of the terminal oxygenase beta subunit in the biphenyl dioxygenase reactivity pattern toward chlorobiphenyls. J. Bacteriol. 180:5828-5835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiang, H., R. E. Parales, and D. T. Gibson. 1999. The alpha subunit of toluene dioxygenase from Pseudomonas putida F1 can accept electrons from reduced ferredoxinTOL but is catalytically inactive in the absence of the beta subunit. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:315-318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kauppi, B., K. Lee, E. Carredano, E. R. Parales, D. T. Gibson, H. Eklund, and S. Samaswamy. 1998. Structure of an aromatic-ring-hydroxylating dioxygenase-naphthalene 1,2-dioxygenase. Structure 6:571-586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kimura, N., A. Nishi, M. Goto, and K. Furukawa. 1997. Functional analyses of a variety of chimeric dioxygenases constructed from two biphenyl dioxygenases that are similar structurally but different functionally. J. Bacteriol. 179:3936-3943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumamaru, T., H. Suenaga, M. Mitsuoka, T. Watanabe, and K. Furukawa. 1998. Enhanced degradation of polychlorinated biphenyls by directed evolution of biphenyl dioxygenase. Nat. Biotechnol. 16:663-666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maeda, T., Y. Takahashi, H. Suenage, A. Suyama, M. Goto, and K. Furukawa. 2001. Functional analyses of Bph-Tod hybrid dioxygenase, which exhibits high degradation activity toward trichloroethylene. J. Biol. Chem. 276:29833-29838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Markus, A., D. Krekel, and F. Lingens. 1986. Purification and some properties of component A of the 4-chlorophenyacetate 3,4-dioxygenase from Pseudomonas species strain CBS. J. Biol. Chem. 261:12883-12888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mermod, N., P. R. Lehrbach, R. H. Don, and K. N. Timmis. 1986. Gene cloning and manipulation in Pseudomonas, p. 325-355. In J. R. Sokatch (ed.), The bacteria, vol. 10. Academic Press, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 36.Mondello, F. J., M. P. Turcich, J. H. Lobos, and B. D. Erickson. 1997. Identification and modification of biphenyl dioxygenase sequences that determine the specificity of polychlorinated biphenyl degradation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:3096-3103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nam, J. W., H. Nojiri, T. Yoshida, H. Habe, H. Yamane, and T. Omori. 2001. New classification system for oxygenase components involved in ring-hydroxylating oxygenations. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 65:254-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Neidle, E. L., C. Hartnett, L. N. Ornston, A. Bairoch, M. Rekik, and S. Harayama. 1991. Nucleotide sequences of the Acinetobacter calcoaceticus benABC genes for benzoate 1,2-dioxygenase reveal evolutionary relationships among multicomponent oxygenases. J. Bacteriol. 173:5385-5395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Neidle, E. L., M. K. Shapiro, and L. N. Ornston. 1987. Cloning and expression in Escherichia coli of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus genes for benzoate degradation. J. Bacteriol. 169:5496-5503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parales, J. V., R. E. Parales, M. S. Resnick, and D. T. Gibson. 1998a. Enzyme specificity of 2-nitrotoluene 2,3-dioxygenase from Pseudomonas sp. strain JS42 is determined by the C-terminal region of the alpha subunit of the oxygenase component. J. Bacteriol. 180:1194-1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Parales, R. E., M. D. Emig, N. A. Lynch, and D. T. Gibson. 1998b. Substrate specificities of hybrid naphthalene and 2,4-dinitrotoluene dioxygenase enzyme systems. J. Bacteriol. 180:2337-2344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Parales, R. E., K. Lee, S. M. Resnick, H. Jiang, D. J. Lessner, and D. T. Gibson. 2000. Substrate specificity of naphthalene dioxygenase: effect of specific amino acids and the active site of the enzyme. J. Bacteriol. 182:1641-1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parales, R. E., S. M. Resnick, C.-L. Yu, D. R. Boyd, N. D. Sharma, and D. T. Gibson. 2000b. Regioselectivity and enantioselectivity of naphthalene dioxygenase during arene cis-dihydroxylation: control by phenylalanine 352 in the α subunit. J. Bacteriol. 182:5495-5504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Reineke, W., and H. J. Knackmuss. 1978. Chemical structure and biodegradability of halogenate aromatic compounds. Substituent effects on 1,2-dioxygenation of benzoic acid. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 542:412-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Romine, M. F., L. C. Stillwell, K.-K. Wong, S. J. Thruston, E. C. Sisk, C. Sensen, T. Gaasterland, J. K. Fredrickson, and J. D. Saffer. 1999. Complete sequence of a 184-kilobase catabolic plasmid from Sphingomonas aromaticivorans F199. J. Bacteriol. 181:1585-1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 47.Sarkar, G., and S. S. Sommer. 1990. The “megaprimer” method of site-directed mutagenesis. BioTechniques 8:404-407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Suenaga, H., T. Watanabe, M. Sato, Ngadiman, and K. Furukawa. 2002. Alteration of regiospecificity in biphenyl dioxygenase by active-site engineering. J. Bacteriol. 184:3682-3688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Timmis, K. N., and D. H. Pieper. 1999. Bacteria designed for bioremediation. Trends Biotechnol. 17:201-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vaillancourt, H. F., S. Han, P. D. Fortin, J. T. Bolin, and L. D. Eltis. 1998. Molecular basis for the stabilization and inhibition of 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl 1,2-dioxygenase by t-butanol. J. Biol. Chem. 273:34887-34895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wolfe, M. D., D. J. Altier, A. Stubna, C. V. Popescu, E. Münck, and J. D. Lipscomb. 2002. Benzoate 1, 2-dioxygenase from Pseudomonas putida: single turnover kinetics and regulation of a two-component Rieske dioxygenase. Biochemistry 41:9611-9626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wolfe, M. D., J. V. Parales, D. T. Gibson, and J. D. Lipscomb. 2001. Single turnover chemistry and regulation of O2 activation by the oxygenase component of naphthalene 1,2-dioxygenase. J. Biol. Chem. 276:1945-1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yamaguchi, M., and H. Fujisawa. 1980. Purification and characterization of an oxygenase component in benzoate 1,2-dioxygenase system from Pseudomonas arvilla C-1. J. Biol. Chem. 255:5058-5063. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zeyer, J. P. R. Lehrbach, and K. N. Timmis. 1985. Use of cloned genes of Pseudomonas TOL plasmid to effect biotransformation of benzoates to cis-dihydrodiols and catechols by Escherichia coli cells. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 50:1409-1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhou, N. Y., J. Al-Dulayymi, M. S. Baird, and P. A. Williams. 2002. Salicylate 5-hydroxylase from Ralstonia sp. strain U2: a monooxygenase with close relationships to and shared electron transport proteins with naphthalene dioxygenase. J. Bacteriol. 184:1547-1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]