Abstract

The recent determination of the crystal structure of the leucine transporter from Aquifex aeolicus (aaLeuT) has provided significant insights into the function of neurotransmitter:sodium symporters. Transport by aaLeuT is Cl− independent, whereas many neurotransmitter:sodium symporters from higher organisms depend on Cl− ions. However, the only Cl− ion identified in the aaLeuT structure interacts with nonconserved residues in extracellular loops, and thus the relevance of this binding site is unclear. Here, we use calculations of pKAs and homology modeling to predict the location of a functionally important Cl− binding site in serotonin transporter and other Cl−-dependent transporters. We validate our model through the site-directed mutagenesis of residues predicted to coordinate the Cl− ion and through the observation of sequence conservation patterns in other Cl−-dependent transporters. The proposed site is located midway across the membrane and is formed by residues from transmembrane helices 2, 6, and 7. It is close to the Na1 sodium binding site, thus providing an explanation for the coupling of Cl− and Na+ ions during transport. Other implications of the model are also discussed.

Keywords: neurotransmitters, neurotransmitter:sodium symporters, serotonin, homology modeling, pKA calculation

The neurotransmitter:sodium symporters (NSS) or SLC6 transporters are a family of membrane proteins that use Na+, K+, and Cl− gradients for the coupled transport of amines and amino acids. Members of this transporter family are responsible for uptake of neurotransmitters, such as glycine, γ-amino butyric acid, serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine, from the synaptic cleft (1). NSS transporters selective for other amino acids have been found to be involved in metabolism, for example, in the larval midgut of the yellow fever vector mosquito (2). Consistent with these important functions, mutations in NSS transporters have been implicated in psychological and digestive disorders, including schizophrenia (3) and Hartnup disorder (4). Furthermore, several NSS transporters have been shown to be targets for psychoactive compounds, including antidepressants, amphetamines, and cocaine (1, 3). Thus, an understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying transport by these proteins is of considerable interest.

Recently, the report of the atomic-resolution x-ray crystal structure of the eubacterium Aquifex aeolicus leucine transporter (aaLeuT) (5) has contributed significantly to understanding of the structure–function relationship for NSS proteins. The structure of aaLeuT reveals 12 transmembrane helices (TM) arranged so as to create enclosed binding sites for two Na+ ions and one leucine approximately midway across the lipid bilayer. Residues forming the leucine binding site are provided by TM 1, 3, 6, and 8, whereas an adjacent binding site for Na+ (the Na1 site) is formed by residues in TM 1, 6, and 7. A second cation binding site (Na2) is located slightly further from the other sites, between TM 1 and 8.

In addition to these sites, a single Cl− ion is found bound to one of the extracellular loops, EL2. The Cl− is >20 Å away from the Na+ and Leu binding sites, and thus it is unclear whether this Cl− binding site is physiologically important. Indeed, amino acid transport by aaLeuT is Cl−-independent (5). In contrast, serotonin transporter (SERT), GABA transporter (GAT1), dopamine transporter, and norephinephrine transporter, among others, are strongly Cl−-dependent (1). The nature of the association of Cl− ions with these proteins during transport remains to be resolved.

Here, we combine calculations of pKAs, homology modeling, and site-directed mutagenesis to identify the binding site for Cl− ions in Cl−-dependent NSS transporters. We first identify buried regions in the structure of aaLeuT that are capable of accommodating a negative charge, by calculating the pKA of the ionizable residues in the protein. We identify an acidic residue, E290, that is likely to be charged in aaLeuT, but is not present in the Cl−-dependent transporters. We then construct a homology model of SERT in which the position of E290 is replaced by a Cl− ion. The location of the Cl− site in this model is consistent with the observed Cl− dependence of known NSS transporters and is supported by site-directed mutagenesis of key residues that are proposed to coordinate the Cl− ion in SERT.

Results

Identification of a Cl− Binding Site in NSS Transporters.

Negatively charged residues in aaLeuT.

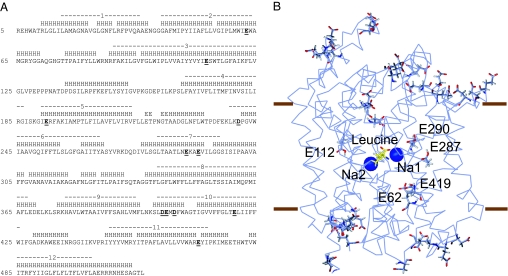

There are eight Glu and three Asp residues in the TM of aaLeuT, the eubacterial transporter for which a crystal structure is available (Fig. 1). Under the assumption that the Cl− site is buried in the protein (as found for the Na+ binding sites), we identified the five acidic residues that are inaccessible to solvent and calculated their pKA by using the MCCE method (6).

Fig. 1.

Positions of negatively charged residues in aaLeuT. (A) Sequence of aaLeuT, with Asp and Glu residues in bold and underlined. TM segments (ends defined by using TMDET) and α-helices (defined by using DSSP) are indicated above the sequences. (B) View of aaLeuT from the plane of the membrane, with the extracellular side toward the top. The backbone of the protein is shown as a Cα trace, and side chains of Asp and Glu residues are shown by using sticks. Buried Glu residues are individually labeled. The approximate extent of the hydrophobic region of the membrane is indicated by brown lines.

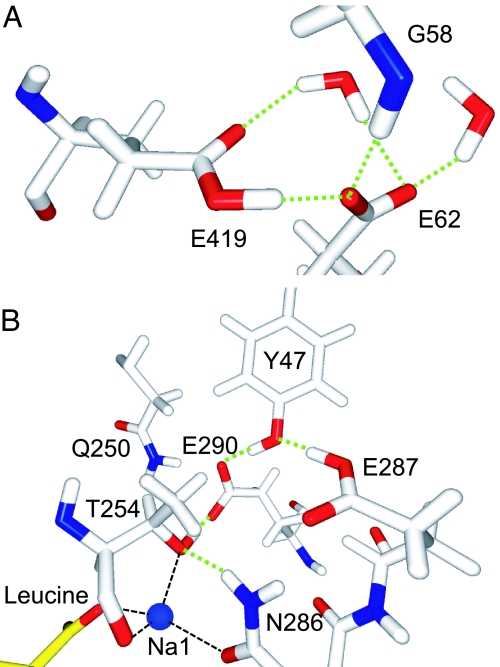

The side chains of E287 and E290 from TM 7 are close to one another in the structure of aaLeuT. In this pair, E287 is predicted to be neutral at pH 7 (pKA > 14), whereas E290 is predicted to be charged (pKA < 1) (Fig. 2). The presence of a buried negative charge at E290 implies some functional role for this residue. The fact that it is replaced by a Ser in most eukaryotic transporters [supporting information (SI) Fig. 5] suggests that its position might be occupied by a Cl− ion in these transporters.

Fig. 2.

Predicted protonation states of five buried Glu residues in aaLeuT. (A) E62–E419 pair. (B) E287–E290 pair. For the E62–E419 pair, the hydrogen is predicted to be midway between the carboxylate oxygen atoms of E62 or E419 and may be bonded to either atom. Potential hydrogen bonds are indicated by green dashed lines.

E62 from TM 2 and E419 from TM 10 are also in close contact with one another in aaLeuT, and as a consequence, their titration behavior is coupled. The pKA calculations indicate that, at pH 7, E62 is ionized (pKA = 6.6) whereas E419 is protonated (pKA > 14). Thus, in effect, the two carboxyl groups share a single proton (Fig. 2). E62 is strictly conserved among the NSS transporters (SI Fig. 5) and has been shown to be critical for transporter function in several different transporters (7–9). In addition, E419 is strongly, although not completely, conserved (SI Fig. 5). Thus, a negative charge on the E62–E419 pair may play an important role in the function of NSS transporters. However, because both E62 and E419 are found in many Cl−-dependent transporters, this position is unlikely to be the site of a functionally important Cl−. Neither is the site of E112 from TM 3, which is predicted to be protonated at pH 7 (pKA = 11.5) and is at a location of significant sequence variability (SI Fig. 5).

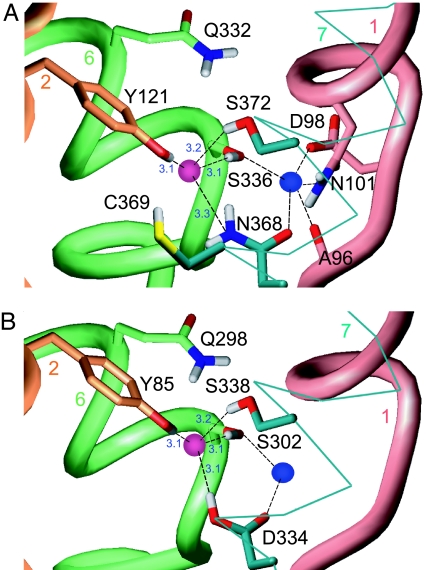

A model of a Cl− binding site in SERT.

The mammalian SERT is one of the best characterized of the Cl−-dependent NSS transporters (10). We generated a homology model of SERT based on aaLeuT with a Cl− ion placed at the coordinates of the E290LeuT carboxylate carbon (Fig. 3A). The atomic structure of the binding site was relaxed by energy minimization (see SI Text). In our model of SERT, Y121, S336, N368, and S372 form a coordination shell for the Cl− ion (Fig. 3A); these correspond to residues Y47, T254, N286, and E290 in aaLeuT.

Fig. 3.

Predicted Cl− binding site in eukaryotic Na+/Cl−-dependent transporters. (A) Model of Cl− binding site in SERT. Distances (Å) are from oxygen or nitrogen atoms to the Cl− ion (magenta sphere). Residues coordinating the Na1 site are also shown. (B) Model of the Cl− binding site in aeAAT1. The Na+ ion in position Na1 is shown as a blue sphere. The backbone of four neighboring helices are shown as worms (TM 1, TM 2, and TM 6) or wire frame (TM 7).

Comparison with Cl− binding sites in other membrane proteins.

The buried Cl− ion binding sites of two other membrane proteins, the ClC Cl−/H+ antiporter (11) and halorhodopsin (12), provide structural precedents for the proposed binding site. In both cases, hydroxyl and/or amine hydrogen atoms form the coordination shell, and a stabilizing positive charge from a Lys side chain is located nearby (12, 13). In the model of SERT, this nearby positive charge originates from the ion at the Na1 site. Interestingly, the position of the Cl− ion in halorhodopsin is occupied by an Asp carboxylate group in the Cl−-independent protein bacteriorhodopsin (SI Fig. 6). This Asp residue replaces a Thr in halorhodopsin and is responsible for the differences in ion selectivity between the two proteins (14). In this respect, halorhodopsin resembles the human NSS transporters, whereas bacteriorhodopsin resembles aaLeuT. Thus, the proposed binding site in the NSS transporters contains properties common to Cl− binding sites in known structures.

Conservation of residues coordinating the Cl− binding site in SERT.

The binding site identified here is formed by residues that are generally evolutionarily conserved, with ConSurf conservation scores of less than −1.1 (SI Fig. 7). Furthermore, the pattern of conservation in both Cl−-independent and Cl−-dependent transporters is consistent with these residues being involved in Cl− binding. Most significantly, S372 from TM 7 in SERT is conserved in all eukaryotic NSS proteins that have been characterized, most of which exhibit Cl−-dependent transport. In contrast, the prokaryotic tryptophan and tyrosine transporters, stTnaT and fnTyt1 (SI Fig. 5), contain Asp and Ala residues, respectively, at the position corresponding to E290; both of these proteins transport amino acids in a Cl−-independent manner (15, 16).

The side-chain hydroxyl from S336 in TM 6 of SERT, at the position equivalent to T254 in the aaLeuT structure, is oriented in our model so that the hydrogen coordinates the Cl− ion, whereas the oxygen coordinates the Na1 site. A hydroxyl at position 254 is highly conserved among known NSS transporters (SI Fig. 5), with the exception of a neutral amino acid transporter, B0AT2. Consistent with this observation, the transport activity of B0AT2 is only weakly Cl−-dependent at saturating substrate concentrations (17, 18).

A third residue that coordinates Cl− in the SERT model is Y121 from TM 2, equivalent to Y47 in the aaLeuT structure. This Tyr is conserved in all known NSS transporters, with the exception of another neutral amino acid transporter, B0AT1 (SI Fig. 5). Again, consistent with this observation, B0AT1 is only weakly Cl−-dependent at saturating substrate concentrations (19, 20).

Finally, the Asn residue corresponding to N286LeuT in TM 7 is predicted by our model to coordinate both the Cl− and Na1 in SERT (N368). This residue is highly conserved in human transporters (SI Fig. 5). Interestingly, N286LeuT is replaced by Asp in several transporters from insects (SI Fig. 5), which are generally Cl−-independent (2, 21). This observation will be discussed in more detail below.

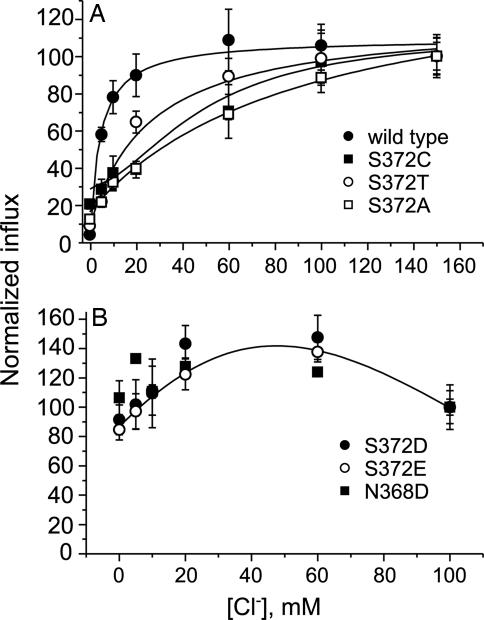

Mutagenesis of S372 in SERT.

We characterized mutants of SERT in which the Ser residue (S372) corresponding to E290 in aaLeuT was replaced. The Cl− dependence of transport was sensitive to the nature of the side chain at this position (Fig. 4). Even the conservative replacement of S372 with Thr increased the KM for Cl−, whereas replacements with Ala and Cys were even more deleterious (Fig. 4A and Table 1). Especially revealing is the effect of replacing S372 with Glu and Asp, which are found at the corresponding positions of Cl−-independent prokaryotic transporters such as aaLeuT (Fig. 4B). Although a small stimulation of transport was observed as Cl− was raised from 0 to 60 mM, higher concentrations reduced influx to the same level as at 0 Cl−. Thus, the presence of a carboxylic side chain at this position essentially prevented physiological Cl− concentrations from stimulating 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) transport. The carboxylate of Glu or Asp apparently occupies the position of a Cl− ion in wild-type SERT, resulting in a transporter that catalyzes Cl−-independent transport, similar to prokaryotic transporters such as aaLeuT and stTnaT.

Fig. 4.

Chloride dependence of SERT mutants. HeLa cells expressing wild-type SERT, S372A, S372C, and S372T (A) or S372D, S372E, and N368D (B) were assayed for 5-HT uptake for 10 min at the indicated Cl− concentrations (as described in Materials and Methods). Transport activity is expressed relative to that at maximal Cl− concentration. Each value represents the mean and SD of three independent experiments, each of which was performed in triplicate or quadruplicate wells.

Table 1.

Activity and expression of SERT mutants

| Mutant | Activity, pmol/min per mg |

Percent activity at [Cl−] = 0 | KM for Cl−, mM | β-CIT binding, % WT | Surface expression, %WT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Cl−] = 0 | [Cl−] = 100 mM | |||||

| WT | 0.037 ± 0.006 | 0.95 ± 0.07 | 4.0 ± 0.7 | 5 ± 2 | 100 ± 4 | 100 ± 3 |

| S372T | 0.06 ± 0.03 | 0.53 ± 0.16 | 11 ± 3 | 21 ± 3 | 86 ± 11 | 92 ± 5 |

| S372A | 0.12 ± 0.05 | 0.56 ± 0.12 | 20 ± 5 | 47 ± 25 | 90 ± 11 | 99 ± 2 |

| S372C | 0.028 ± 0.003 | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 26 ± 7 | 88 ± 34 | 85 ± 9 | 90 ± 4 |

| S372D | 0.024 ± 0.004 | 0.029 ± 0.003 | 83 ± 9 | — | 81 ± 8 | 104 ± 2 |

| S372E | 0.031 ± 0.008 | 0.039 ± 0.012 | 79 ± 2 | — | 83 ± 5 | 103 ± 1 |

| S372L | 0.003 ± 0.004 | 0.006 ± 0.001 | — | — | 69 ± 14 | 120 ± 14 |

| N368D | 0.036 ± 0.001 | 0.039 ± 0.004 | 91 ± 1 | — | 83 ± 4 | 110 ± 11 |

| N368I | 0.000 ± 0.001 | 0.002 ± 0.001 | — | — | 93 ± 5 | 106 ± 21 |

| N368L | 0.002 ± 0.002 | 0.003 ± 0.001 | — | — | 99 ± 3 | 123 ± 20 |

Initial rates of transport (10 min) were measured in HeLa cells expressing the WT or indicated mutants as described in Materials and Methods and expressed in terms of total cell protein. For mutants with measurable activity, the percent of activity at zero Cl− was calculated relative to that at maximal Cl−. β-CIT binding was measured in similar cells. Binding to cells expressing WT SERT was 0.38 ± 0.02 pmol per mg of cell protein. Surface expression was estimated by densitometry of Western blots of biotinylated SERT after subtraction of untransfected control values. Each value represents the mean and SD of three independent experiments, each of which was performed in triplicate or quadruplicate wells.

Surface expression levels for these mutants and others are shown in Table 1, along with inhibitor binding results. All mutants tested were expressed at the cell surface, and all bound 2β-carbomethoxy-3β-(4-[125I]-iodophenyl)tropane (β-CIT) at wild-type levels, indicating that they are correctly folded. Relative transport activities (Table 1) show that mutation of S372 leads to decreased catalytic activity, which is low in S372D and S372E and absent in S372L.

The Role of an Asp at the Position of N286LeuT.

Mutagenesis of N368 in SERT.

As mentioned above, several insect and prokaryotic transporters contain an Asp residue at the position of N286 in aaLeuT (SI Fig. 5). We therefore tested a SERT mutant in which the equivalent residue, N368, was converted to Asp (22). In Fig. 4B we show that this change led to an essentially Cl−-independent phenotype. Thus, insertion of a carboxylate at either of two positions proposed to coordinate the cotransported Cl− ion, S372 or N368, prevented Cl− from stimulating 5-HT transport. These results are consistent with the proposal that transporters with carboxylic amino acids at these positions do not couple Cl− to transport.

Calculation of the pKA of D334 in the Aedes aegypti phenylalanine transporter (aeAAT1).

We built a homology model of phenylalanine-selective AAT1 from A. aegypti, the yellow fever vector mosquito (aeAAT1), which is one of the insect transporters that contains an Asp at the position corresponding to 286 in LeuT. This residue corresponds to D334 in aeAAT1 (Fig. 3B). The very low calculated pKA (<1) for D334 in our model indicates that it is very likely to be charged at pH 7 if no Cl− ion is present in the proposed site. However, if a Cl− ion is placed in the site, the predicted pKA of D334 shifts to >14. These results thus suggest that the region near D334 can only accommodate a single negative charge, either a Cl− ion or a deprotonated D334 side chain. This, in turn, implies that substrate and cation binding should be as efficient under high Cl− and low-pH conditions, as under low Cl− and high-pH conditions.

Fig. 4B shows that, for SERT mutants in which S372 or N368 is replaced by a negatively charged residue, the amount of substrate influx actually decreases at high Cl− concentrations. Similarly, in aeAAT1, the presence of Cl− has the effect of slightly reducing the amplitude of the substrate-induced currents, rather than increasing it (2). We speculate that this effect may be caused by the requirement that D334 or another negatively charged residue be protonated when Cl− is bound, which may provide an additional kinetic barrier to transport. However, it is also possible that Cl− ions bind to an alternate site in the protein when a negatively charged residue is present in the proposed binding site.

Discussion

There is strong evidence for the validity of the location of the Cl− binding site in SERT that we have proposed. As discussed above, the conservation of the residues coordinating the Cl− ion correlates strongly with the Cl− dependence of the various NSS transporters and the transport properties of the various site-directed mutants reported above are also in accord with our model. We have built homology models of other Cl−-dependent human transporters, including transporters for GABA (GAT1) and glycine (GlyT1b) (data not shown) and the predicted binding site is always very similar to that in SERT (see Fig. 3), suggesting that it is present in all related transporters. It is of interest that the proposed Cl− binding site is located approximately midway across the lipid bilayer, which is consistent with the notion that the substrate and transported ions have alternating access to each side of the membrane.

The Cl− binding site is ≈5 Å from the Na1 binding site, providing a simple explanation for how the two ions are coupled, and how Cl− can stabilize Na+ binding (8). Indeed, our calculations suggest that the electrostatic interaction energy between the two sites is −11 kcal/mol, indicating a very large degree of coupling.

The transport activity of mutants of S372 and N368 in SERT also supports the hypothesis of a Cl− binding site close to Na1. Even highly conservative mutations lead to a decrease in the ability of Cl− to stimulate 5-HT transport (Fig. 4A and Table 1). This finding suggests that the Cl− binding affinity is affected by altering the character of the ion binding site. Significantly, replacement of S372 with Glu or Asp, or N368 with Asp (as found in Cl−-insensitive transporters), results in transporters that are relatively independent of Cl− (Fig. 4B). Thus, the presence of Asp or Glu in the proposed binding site may constitute an electrostatic barrier to Cl− binding (Table 1). However, the activity of S372E, S372D, and N368D is low (Table 1), similar to the rate of wild-type SERT in the absence of added Cl−. (It is possible that some Cl− remained in our putative zero Cl− solutions, and that wild-type transport would be even lower if that contaminating Cl− were removed.) Replacing the negative charge of Cl− with a carboxylate may be sufficient to stabilize the Na+ ion at Na1, but may not completely satisfy other requirements for transport. For example, the Cl− ion also functions as a trigger of the conformational changes that deliver 5-HT to the cytoplasmic side of the plasma membrane (10). Another possible interpretation of their weak Cl− dependence is that the S372E, S372D, and N368D mutants merely provide a steric barrier to Cl− binding. However, the S372L mutant, whose aliphatic Leu side chain has a similar buried volume as the carboxylate side chain of Glu in S372E, exhibits no transport activity and the same is true for N368L and N368I (Table 1). Thus, either a Cl− ion or a carboxylate side chain appears to be required in the binding site for transport to proceed.

Work from the laboratory of Baruch Kanner (personal communication) indicates that introduction of a carboxylic residue at the position corresponding to S372 of SERT in GAT1 and GAT4 or the dopamine transporter allows transport in the absence of chloride. The N327D mutant in GAT1, corresponding to SERT N368D, was also Cl−-independent, indicating that the function of these residues is conserved among neurotransmitter transporters.

Previously, the Tyr at position 47 of aaLeuT has been mutated to Cys or Ala in several monoamine transporters, including SERT (Y121), norepinephrine transporter (Y98), and dopamine transporter (Y102). These mutations resulted in proteins in which transport was defective (9, 23–25). However, cell surface expression was also diminished for these mutants, which suggests that the steric bulk of this Tyr is required for the structural integrity of NSS transporters. It will be of interest to characterize the Cl−dependence of SERT mutations of residue Y121 and thus to further refine the position of the Cl- binding site.

Finally, although the model we have constructed for SERT is clearly inaccurate at the level of 1- to 2-Å resolution, it has provided us with a series of testable hypotheses that have been confirmed with the analysis of site-directed mutants. More generally, the combined use of homology models with analysis of sequence conservation patterns can be of great value in the design and interpretation of experiments (26, 27). These models can then be further refined as new data become available, an iterative procedure that we hope will prove effective in future studies on SERT.

Materials and Methods

Sequence Alignments.

The alignments for the homology modeling and analysis (SI Fig. 5) were based on those of Beuming et al. (28), with minor adjustments of the stems of loops IL1, EL2, EL4a, IL4, and EL5.

Construction of SERT and aeAAT1 Homology Models.

Homology models were constructed of human SERT and aeAAT1. Initial models were built by using the Nest program (29), using the aaLeuT structure [Protein Data Bank entry 2a65 (5)] as the template. Details of the models can be found in SI Table 2. Two Na+ ions and one Cl− ion were added to each model. For aeAAT1, a phenylalanine substrate was also added by assuming the same backbone coordinates as for the leucine in aaLeuT. For SERT, 5-HT was added in two distinct orientations: (i) with the NH3+ group close to Asp-98, and (ii) with the 3+ group close to S437; these differences were found to have no effect on the predicted Cl− site (data not shown). The protein–ligand complexes were energy-minimized by using PLOP (30). Optimization of side-chain and loop conformations is described in SI Text.

Homology Model Accuracy.

The sequence identities of aeAAT1 and SERT to the aaLeuT template are 25–27% in the TM regions and 19–21% over the entire sequence (SI Table 2). A recent study of membrane protein homology modeling provided a benchmark for the expected accuracy of a model based on the sequence identity between the target and its template (31). See SI Fig. 8, SI Table 3, and SI Text for more details. Based on these benchmarks, the TM regions of the NSS transporters models are expected to deviate from their native structures by 1– to 2.5-Å Cα rmsd.

Evolutionary Conservation Analysis.

Conservation scores for each position in the NSS transporters were calculated by using ConSurf version 3.0 (32). For this analysis, sequence homologues of aaLeuT were obtained by using five iterations of PSI-BLAST on the National Center for Biotechnology Information nonredundant protein database (from June 4, 2007), with an inclusion E value of 0.0005. After removing sequences below the structural similarity threshold of Abagyan and Batalov (33), and above 65% identity, a multiple sequence alignment was generated for the remaining 362 sequences, using Muscle (34).

pKA calculations.

The pKA of ionizable groups were predicted by using MCCE version 2.0 (6). MCCE uses the DelPhi program version 4 (35) and PARSE charges and radii (36). The aaLeuT structure and the aeAAT1 and SERT homology models were each placed in a 25-Å-thick slab of overlapping spheres to mimic the low-dielectric bilayer core, according to ref. 13. Crystallographic waters in aaLeuT were included explicitly if their solvent accessibility was zero. All atoms that were included explicitly in the calculations were assigned an internal dielectric constant of 4, as is standard in MCCE calculations. Side-chain conformations were fixed according to the initial structures. Although quantitative changes were observed when using side-chain conformational sampling, larger numbers of explicit waters, or different dielectric constants, our conclusions were unaffected by these differences (data not shown).

Calculation of Electrostatic Interaction Energies.

The electrostatic interaction energy between Na1 and E290 in aaLeuT was calculated as the product of the charge of the Na+ ion and the potential caused by the partial charges of E290 at the position of Na1. This potential was generated in the presence of the dielectric distribution of the protein, membrane, and all other substrates, as described above.

SERT Mutants.

Site-directed mutagenesis of rat SERT was performed by using the QuikChange protocol (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). All mutants were sequenced to verify the accuracy of the procedure. Transport measurements were performed as described (37). Briefly, HeLa cells transfected with SERT mutant DNA using the vaccinia T7 system (38) were grown in 24- or 48-well plates, rinsed into medium containing [3H]5-HT and the indicated Cl− concentration, incubated 10 min at 25°C, rinsed again, and counted. Transport media with altered Cl− concentrations were supplemented with the appropriate concentration of isethionate to maintain isotonicity.

Cell surface expression was determined as described (39) by labeling cell-surface proteins with biotin by using Sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin (Pierce, Rockford, IL), lysing the cells with detergent and isolating the biotinylated proteins with streptavidin agarose. Surface expression was estimated by Western blotting of the mature biotinylated proteins using an antibody directed toward the C-terminal FLAG tag on rat SERT.

Binding of β-CIT to HeLa cells expressing SERT mutants was measured as described (37). Briefly, cells expressing the various mutants were grown in 96-well plates, washed, and incubated with [125I]β-CIT for 40 min followed by washing and counting the cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank E. Gouaux for providing access to structural data before release; J. Mao, Y. Song, E. Alexov, and M. Jacobson for technical advice; and J. Faraldo-Gómez and M. Kosloff for helpful discussions. B.H. and L.R.F. were supported by National Science Foundation Grant MCB-0416708. G.R. and Y.-W.Z. were supported by National Institutes of Health Grant DA007295, and S.T. was supported by grants from the National Association for Autism Research and Autism Speaks.

Abbreviations

- NSS

neurotransmitter:sodium symporters

- TM

transmembrane helix

- aaLeuT

Aquifex aeolicus leucine transporter

- SERT

serotonin transporter

- GAT

GABA transporter

- aeAAT1

Aedes aegypti phenylalanine transporter

- 5-HT

5-hydroxytryptamine

- β-CIT

2β-carbomethoxy-3β-(4-[125I]-iodophenyl)tropane.

Note Added in Proof:

Studies subsequent to submission of this paper indicate that mutation of D268 in stTnaT (corresponding to E290 in aaLeuT) to Ser, as in SERT, converts this Cl−-insensitive bacterial transporter to one that is largely Cl−-dependent (G.R., A. Rizwan and P. Mandela, unpublished work). This finding provides further confirmation of our identification of the Cl− binding site by creating the Cl− binding site of a neurotransmitter transporter in a bacterial amino acid transporter.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0705600104/DC1.

References

- 1.Reith MEA, editor. Neurotransmitter Transporters: Structure, Function, and Regulation. Totowa, NJ: Humana; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boudko DY, Kohn AB, Meleshkevitch EA, Dasher MK, Seron TJ, Stevens BR, Harvey WR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:1360–1365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405183101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Surratt CK, Ukairo OT, Ramanujapuram S. AAPSJ. 2005;7:E739–E751. doi: 10.1208/aapsj070374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bröer S. Neurochem Int. 2006;48:559–567. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2005.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamashita A, Singh SK, Kawate T, Jin Y, Gouaux E. Nature. 2005;437:215–223. doi: 10.1038/nature03978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alexov EG, Gunner MR. Biophys J. 1997;72:2075–2093. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78851-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Korkhov VM, Holy M, Freissmuth M, Sitte HH. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:13439–13448. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511382200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keshet GI, Bendahan A, Su H, Mager S, Lester HA, Kanner BI. FEBS Lett. 1995;371:39–42. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00859-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sen N, Shi L, Beuming T, Weinstein H, Javitch JA. Neuropharmacology. 2005;49:780–790. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rudnick G. J Membr Biol. 2007;213:101–110. doi: 10.1007/s00232-006-0878-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dutzler R, Campbell EB, Cadene M, Chait BT, MacKinnon R. Nature. 2002;415:287–294. doi: 10.1038/415287a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kolbe M, Besir H, Essen LO, Oesterhelt D. Science. 2000;288:1390–1396. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5470.1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faraldo-Gómez JD, Roux B. J Mol Biol. 2004;339:981–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sasaki J, Brown LS, Chon YS, Kandori H, Maeda A, Needleman R, Lanyi JK. Science. 1995;269:73–75. doi: 10.1126/science.7604281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Androutsellis-Theotokis A, Goldberg NR, Ueda K, Beppu T, Beckman ML, Das S, Javitch JA, Rudnick G. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:12703–12709. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206563200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quick M, Yano H, Goldberg NR, Duan L, Beuming T, Shi L, Weinstein H, Javitch JA. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:26444–26454. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602438200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bröer A, Tietze N, Kowalczuk S, Chubb S, Munzinger M, Bak LK, Bröer S. Biochem J. 2006;393:421–430. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takanaga H, Mackenzie B, Peng J-B, Hediger MA. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 2005;337:892–900. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.09.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bohmer S, Bröer A, Munzinger M, Kowalczuk S, Rasko JEJ, Lang F, Bröer S. Biochem J. 2005;389:745–751. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Camargo SM, Makrides V, Virkki L, Forster I, Verrey F. Pflügers Arch Eur J Physiol. 2005;451:338–348. doi: 10.1007/s00424-005-1455-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soragna A, Mari SA, Pisani R, Peres A, Castagna M, Sacchi VF, Bossi E. Am J Physiol. 2004;287:C754–C761. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00016.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Penado KMY, Rudnick G, Stephan MM. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:28098–28106. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.43.28098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sato Y, Zhang Y-W, Androutsellis-Theotokis A, Rudnick G. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:22926–22933. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312194200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sucic S, Bryan-Lluka LJ. J Neurochem. 2005;94:1620–1630. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Itokawa M, Lin Z, Cai N-S, Wu C, Kitayama S, Wang J-B, Uhl GR. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;57:1093–1103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petrey D, Honig B. Mol Cell. 2005;20:811–819. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vadyvaloo V, Smirnova IN, Kasho VN, Kaback HR. J Mol Biol. 2006;358:1051–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.02.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beuming T, Shi L, Javitch JA, Weinstein H. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70:1630–1642. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.026120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Petrey D, Xiang ZX, Tang CL, Xie L, Gimpelev M, Mitros T, Soto CS, Goldsmith-Fischman S, Kernytsky A, Schlessinger A, et al. Proteins. 2003;53:430–435. doi: 10.1002/prot.10550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacobson MP, Friesner RA, Xiang Z, Honig B. J Mol Biol. 2002;320:597–608. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00470-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Forrest LR, Honig B. Proteins. 2005;61:296–309. doi: 10.1002/prot.20601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Landau M, Mayrose I, Rosenberg Y, Glaser F, Martz E, Pupko T, Ben-Tal N. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W299–W302. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abagyan RA, Batalov S. J Mol Biol. 1997;273:355–368. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Edgar RC. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rocchia W, Alexov E, Honig B. J Phys Chem B. 2001;105:6507–6514. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sitkoff D, Sharp KA, Honig H. J Phys Chem. 1994;98:1978–1988. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Y-W, Rudnick G. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:30807–30813. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504087200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blakely RD, Clark JA, Rudnick G, Amara SG. Anal Biochem. 1991;194:302–308. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(91)90233-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen J-G, Liu-Chen S, Rudnick G. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:12675–12681. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.20.12675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.