Abstract

AcrAB-TolC is the major, constitutively expressed efflux protein complex that provides resistance to a variety of antimicrobial agents in Escherichia coli. Previous studies showed that AcrA, a periplasmic protein of the membrane fusion protein family, could function with at least two other resistance-nodulation-division family pumps, AcrD and AcrF, in addition to its cognate partner, AcrB. We found that, among other E. coli resistance-nodulation-division pumps, YhiV, but not MdtB or MdtC, could also function with AcrA. When AcrB was assessed for the capacity to function with AcrA homologs, only AcrE, but not YhiU or MdtA, could complement an AcrA deficiency. Since AcrA could, but YhiU could not, function with AcrB, we engineered a series of chimeric mutants of these proteins in order to determine the domain(s) of AcrA that is required for its support of AcrB function. The 290-residue N-terminal segment of the 398-residue protein AcrA could be replaced with a sequence coding for the corresponding region of YhiU, but replacement of the region between residues 290 and 357 produced a protein incapable of functioning with AcrB. In contrast, the replacement of residues 357 through 397 of AcrA still produced a functional protein. We conclude that a small region of AcrA close to, but not at, its C terminus is involved in the interaction with its cognate pump protein, AcrB.

The genomes of Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa each encode many multiple drug efflux systems that provide resistance to structurally unrelated noxious molecules (24, 25, 29, 31). Some of these systems have a tripartite structure and are composed of (i) a pump embedded in the cytoplasmic membrane and belonging to either the resistance-nodulation-division (RND) (32) or the major facilitator superfamily, (ii) a periplasmic accessory protein belonging to the membrane fusion protein (MFP) family (6), and (iii) an outer membrane channel belonging to the outer membrane factor family (28). The coordinated function of these three components results in the extrusion of antimicrobial agents across the periplasmic space and outer membrane, directly into the extracellular milieu (24, 37). In both organisms, there is a major, constitutively expressed system with a wide specificity, AcrAB-TolC in E. coli (16, 17, 27) and MexAB-OprM in P. aeruginosa (24). Other systems, often with partially redundant specificity, are expressed poorly in the usual laboratory media (2, 13, 23, 26).

The components of the AcrAB-TolC system, AcrA, AcrB, and TolC, correspond to an MFP, an RND pump, and an outer membrane channel, respectively (24, 36). Unlike homologous systems in P. aeruginosa, in which all components of the tripartite system are located within a single operon, in E. coli the acrAB genes occur in tandem as an operon, whereas tolC is located elsewhere in the genome. This genetic organization is consistent with the observation that E. coli uses TolC as a common outer membrane channel for all known tripartite efflux systems (24, 37). Thus, all RND pump genes in E. coli occur together in tandem with a gene for the cognate MFP, with the exception of acrD (7, 30).

The function of the AcrB transporter has been studied in depth. Biochemical studies with proteoliposome reconstitution (36) showed that AcrB was capable of extruding substrates embedded in the lipid bilayer, even phospholipid molecules modified in their head groups, by using proton flux as the source of energy. Structural studies by X-ray crystallography (22) showed that AcrB exists as a trimer, with each monomer containing a huge periplasmic domain with a height of about 70 Å. Furthermore, a likely conduit for substrates, called the vestibule, between neighboring periplasmic domains and just outside the external membrane surface, leads to the center of the trimer, where the substrates could be extruded outward through the funnel-like opening. Finally, the top of the funnel appears to fit with the inner end of the periplasmic tunnel of the TolC trimer, whose structure was elucidated by X-ray crystallography (14). These results suggest the main pathway that substrates follow: substrates partially embedded in the external leaflet of the bilayer travel laterally through the vestibule of AcrB to reach the central cavity to become bound to its wall (34) and are then extruded through the AcrB funnel, the periplasmic tunnel, and the outer-membrane-traversing channel of TolC into the external medium.

The precise role of the periplasmic AcrA component, however, is not clear, although in intact cells it is absolutely needed for drug efflux (16). Because it has an elongated shape (the length was estimated to be as much as 200 Å) (35) and because it is a lipoprotein whose N terminus is associated with the inner membrane (16), it has often been postulated to function by connecting the outer and inner membranes, and its stimulatory effect on AcrB activity in vitro has also been interpreted as a consequence of this membrane-bridging effect (36). However, recent in vitro reconstitution studies with an AcrB homolog, AcrD, suggest that the association of AcrA activates AcrD pump activity under conditions where membrane bridging or fusion can play no role (J. R. Aires and H. Nikaido, unpublished data). This effect requires a specific interaction between AcrA and an RND pump, either AcrB or AcrD. With this information in mind, we studied the domain of AcrA that was necessary for the function of AcrB by using the domain interchange analysis previously used by us for the study of AcrB and AcrD (7). For the domain exchange analysis, we needed a homolog of AcrA that does not activate the AcrB pump. This requirement is addressed in the first part of this study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Culture techniques and strains.

E. coli strains used in this study (Table 1) were maintained at −80°C in 15% (vol/vol) glycerol for cryoprotection. They were grown at 37°C (except when temperature-sensitive plasmids were used; Table 1) either in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, 1% NaCl) or in 2× YT broth (1.6% tryptone, 1% yeast extract, 0.5% NaCl) or on LB agar (1.5%) plates.

TABLE 1.

E. coli strains and plasmid constructs

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s) | Relevant genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strains | |||

| DH5α | Standard host strain for cloning | φ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF) endA1 recA1 | Gibco-BRL |

| AG102 | Derived from AG100 | marR1 | 9 |

| AG102A | Derived from AG102 | marR1 ΔacrAB::kan | 27 |

| AG102MB | Derived from AG102 | marR1 actB::kan | 7 |

| HNCE1a | Derived from AG102MB | marR1 acrB::kan ΔacrD | 7 |

| HNCE1b | Derived from HNCE1a | marR1 acrB::kan ΔacrD acrA::cat | 7 |

| HNCE3 | Derived from AG102 | marR1 ΔacrA | This study |

| HNCE5 | Derived from AG102A | marR1 ΔacrAB::kan ΔyhiV::cat | This study |

| Plasmidsa | |||

| pKD46 | λ red recombinase expression plasmid; ara-inducible expression, temperature-sensitive replication | amp λ(γ, β, exo) araC | 5 |

| pKD3 | Template plasmid; FRT-flanked cat | amp cat oriRγ | 5 |

| pCP20 | FLP expression plasmid; temperature-sensitive replication and FLP synthesis | amp flp | 5 |

| pSportIb | High-copy-number cloning and expression vector; lac-inducible expression | amp lacI | Gibco-BRL |

| pAcrBc | Clone from DH5α | acrB | 7 |

| pAcrDc | Clone from DH5α | acrD | 7 |

| pYhiVc | Clone from DH5α | yhiV | This study |

| pMdtBCc | Clone from DH5α | mdtB mdtC | This study |

| pAcrAc | Clone from DH5α | acrA | This study |

| pAcrEc | Clone from DH5α | acrE | This study |

| pYhiUc | Clone from DH5α | yhiV | This study |

| pMdtAc | Clone from DH5α | mdtA | This study |

See Fig. 3 for plasmids expressing AcrA-YhiU chimeras.

Plasmid vector used for all constructs created in this study.

The lac-inducible promoter of pSportI controls the expression of all cloned gene constructs created in this study.

Construction of native RND and MFP clones.

Analysis of the GenBank entries for yhiV, acrA, acrE, and yhiU did not reveal any XbaI or BamHI sites within their open reading frames. In addition, mdtB and mdtC did not contain XbaI or HindIII sites, and mdtA did not contain any BamHI sites. Oligonucleotide primers engineered with these respective sites were used to amplify, by PCR, the genes under standard conditions with either the long and accurate Advantage cDNA Polymerase Mix (Clontech) or PfuTurbo polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). The amplified DNA was purified, digested with the respective restriction enzyme(s) (New England Biolabs), and ligated into similarly digested but dephosphorylated pSportI DNA (Gibco-BRL) (Table 1) so that the genes would come under the control of the lac-inducible promoter. DH5α cells were electroporated with the ligated DNA and plated on LB agar containing 100 μg of ampicillin/ml for selection. Plasmid DNA from several transformants was digested with the respective enzyme(s), electrophoresed in 1% agarose gels containing 0.5 μg of ethidium bromide/ml, and screened for appropriately sized inserts. For mdtA, clones containing inserts of approximately 1,500 bp were also screened by sequencing through the polylinker with standard primer T7F for directionality.

Simultaneous overexpression of YhiU and YhiV.

HNCE3 cells harboring pYhiU were grown in 2× YT broth, and YhiU expression was induced with 0.1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG; Gibco-BRL) for 2 h. The cells were harvested, washed three times in ice-cold 10% glycerol, and used for electroporation of pYhiV DNA. Transformants were selected on LB agar plates containing 75 μg of ethidium bromide/ml and 0.1 mM IPTG. Several transformants were picked and restreaked on plates containing 100 μg of erythromycin/ml and 0.1 mM IPTG.

Mutagenesis.

A nonpolar E. coli deletion mutation at the acrA locus (strain HNCE3; Table 1) was generated by a procedure based on the λ red genes for recombination (5). AG102 cultures containing pKD46 were grown at 30°C, induced with 10 mM l-arabinose to express the red genes, and made competent for electroporation. Linear DNA containing cat flanked by the FLP recognition target (FRT) sites was amplified by standard PCR from pKD3 with hybrid primers homologous at the 3′ end to sequences in pKD3 and at the 5′ end to sequences at the acrA locus. Transformants were selected on LB agar containing 25 μg of chloramphenicol/ml and screened for the expected integrations by PCR. The cat resistance gene was eliminated at the FRT sites with pCP20, which expresses the FLP recombinase. Since pKD46 and pCP20 are both temperature-sensitive replicons (Table 1), they were cured from E. coli strains by growth at 37 and 43°C, respectively. The remaining “scar” sequence at the acrA locus did not contain transcription termination sequences (5) and therefore did not affect native acrB expression. A yhiV deletion strain (HNCE5) was constructed by a similar procedure from acrAB deletion strain AG102A (27), but without the elimination of the cat marker in the last stage.

Chimeric fusions of MFP genes in which linear amino-terminal or carboxyl-terminal domains were replaced precisely and in frame with those of the homologous gene were constructed by a two-step PCR protocol as described in detail previously (7, 8). Briefly, the first step involved creating a “megaprimer” by amplifying from a homologous gene (in our experiments, yhiU) DNA that will replace the corresponding domain in the native gene (in our experiments, acrA). This step was accomplished with hybrid primers containing 5′ extensions that were designed in frame with sequences from the homologous gene but that complemented the exact start and end sites of the intended integration into the native gene. In the second step, the megaprimer was used in a long, whole-plasmid amplification with Advantage cDNA Polymerase Mix and the plasmid-encoded native gene, acrA, as a template. Amplified DNA from this reaction was digested with DpnI, which recognizes methylated DNA and eliminates template DNA encoding the native pump protein (7). Newly synthesized plasmids encoding chimeric proteins were transformed into DH5α cells and screened by sequencing for the expected domain replacements.

DNA primers, sequencing, and analysis.

Oligonucleotide primers used for cloning and mutagenesis techniques were generated by Elim Biopharmaceuticals, Inc. (Hayward, Calif.). Plasmid constructs were sequenced by using an automated method through the polylinker junction to verify insert coding capacity and orientation (Elim Biopharmaceuticals). Plasmids bearing MFP mutants (Table 1) were also sequenced through the chimeric junctions (see above section on mutagenesis) to verify that the expected mutation was obtained. The DNA sequence was analyzed for open reading frames, restriction enzyme sites, and predicted protein sequence with DNAman version 4.11 (Lynnon Biosoft).

RT-PCR.

Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR was carried out essentially as described before (15). Primers were designed to amplify internal fragments of about 400 to 500 nucleotides. The primer sequences began at residues 181 and 586 for acrA after the translation start point, residues 126 and 593 for yhiU, and residues 60 and 549 for acrE.

Drug resistance.

E. coli strains harboring pSportI-derived plasmids were tested for drug resistance by using solid media containing a drug gradient. Linear concentration gradients of drugs were prepared in square LB agar plates (3, 9) containing 0.1 mM (final concentration) IPTG. The lower layer was prepared as an LB agar slant containing the specified concentration of drug; this layer was overlaid with drug-free LB agar to create even, level plates. Inoculum cultures were grown to mid-log phase in 1 ml of 2× YT broth containing 100 μg of ampicillin/ml and streaked as a linear, thick inoculum across the plates, parallel with the drug gradient. Bacterial growth across the plates from low to high drug concentrations was recorded in millimeters after 24 h at 37°C. In order to confirm the conclusions obtained by use of gradient plates, a conventional serial twofold broth dilution assay was also run for selected strains.

Preparation and analysis of crude membrane extracts.

Crude envelope fractions of E. coli cultures expressing plasmid-encoded RND pumps, MFPs, and chimeric MFPs were prepared from overnight cultures grown in 5 ml of LB broth and induced with 0.1 mM IPTG. The cultures were harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 × g and resuspended in 10−1 the original volume of 1 mM EDTA- 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride- 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) buffer. The cell suspension was sonicated for 1 to 2 min, followed by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C, during which the crude envelope fractions were pelleted. The fractions were solubilized at room temperature in a 10−2 volume of the same buffer containing 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). Membrane proteins were resolved in SDS-7.5 or 10% polyacrylamide gels, which were then stained with Coomassie blue.

Chemicals.

Chemicals, including antimicrobial agents, were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. unless indicated otherwise.

RESULTS

Search for AcrA homologs that do not activate AcrB.

We wanted to find out which domains of AcrA are required for the activation of (or cooperation with) the AcrB pump. In order to carry out this study by the domain exchange method (7), we needed a close homolog of AcrA that did not work together with the AcrB pump. The E. coli genome contains six pump systems in the RND family, and five of the pump genes occur together with the gene for the cognate MFP and sometimes with genes for other proteins. These operons are acrAB, acrEF, yhiUV, mdtABC, and cusCFBA (ylcBCD-ybdE). In contrast, the acrD gene occurs alone, without the gene for the MFP nearby. Because the cus operon functions in the efflux of the copper ion (11) and because its components are not closely related to those of the AcrAB system, we excluded this system from our analysis.

We thus tested four MFPs, AcrA, AcrE, YhiU, and MdtA, for their ability to work together with the AcrB transporter (Table 2). Because most of the analysis in this study was carried out with gradient plates, we show the MICs of various drugs, determined by the standard serial twofold broth dilution method, in Table 3, to validate the conclusions drawn from the use of gradient plates. The host used had a nonpolar deletion of acrA but contained wild-type alleles of acrE, yhiU, and mdtA. The presence of these latter alleles did not affect the results, because the acrE and mdtA genes are known to be expressed at essentially undetectable levels in laboratory media (2, 18) (also compare the gene disruption data of Sulavik et al. [31] with the overexpression data of Nishino and Yamaguchi [25]). RT-PCR analysis showed that yhiU was expressed at a level more than 1 order of magnitude lower than acrA (results not shown), and Table 3 shows that the deletion of chromosomal yhiV had no or only a marginal effect on resistance to bile salts and erythromycin, typical substrates for the YhiUV pump (25). Furthermore, the YhiUV system cannot produce significant levels of resistance to some agents that are pumped out by AcrAB, such as tetracycline (Table 3).

TABLE 2.

Gradient plate analysis of abilities of E. coli MFP members to activate AcrB-mediated drug effluxa

| Drug | Concn (μg/ml) in lower layer | Length of growth zone (mm) for an HNCE3 (nonpolar ΔacrA) host containing:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pSPORTI | pAcrA | pAcrE | pYhiU | pMdtA | ||

| Cholate | 8,000 | 45 | 80 | 80 | 40 | 38 |

| Taurocholate | 6,500 | 35 | 80 | 80 | 40 | 38 |

| Fusidic acid | 35 | 20 | 80 | 45 | 15 | 8 |

| Novobiocin | 30 | 30 | 80 | 59 | 25 | 25 |

| Crystal violet | 12 | 23 | 80 | 80 | 20 | 20 |

| Ethidium bromide | 50 | 21 | 80 | 80 | 18 | 20 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.01 | 46 | 80 | 80 | 44 | 45 |

| Chloramphenicol | 12 | 17 | 80 | 32 | 14 | 15 |

| Erythromycin | 30 | 50 | 80 | 80 | 47 | 45 |

| Tetracycline | 6 | 27 | 80 | 35 | 25 | 22 |

The length of the plate was 80 mm. Thus, a value of 80 means that the strain grew to the highest concentration found in the plate and that the MIC could have been higher than the concentration in the lower layer. Values shown in boldface represent cells in which the expression of MFP genes produced drug resistance higher than that cells harboring the pSportI vector alone.

TABLE 3.

MICs of various drugs in HNCE3 (ΔacrA) and related strains

| Strain | MIC (μg/ml) of:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cholic acid | Taurocholic acid | Novobiocin | Ciprofloxacin | Erythromycin | Tetracycline | |

| HNCE3 (pSportI) | 6,250 | 12,500 | 8 | 0.02 | 64 | 4 |

| HNCE3 (pAcrA) | 25,000 | 100,000 | 512 | 0.32 | >512 | 32 |

| HNCE3 (pYhiU) | 6,250 | 12,500 | 16 | 0.01 | 64 | 4 |

| HNCE3 (pYhiV) | 6,250 | 6,250 | 4 | 0.01 | 32 | 2 |

| HNCE3 (pYhiU, pYhiV) | 50,000 | 100,000 | 256 | 0.16 | >512 | 8 |

| AG102A | 6,250 | 6,250 | 4 | 0.01 | 32 | 1 |

| HNCE5 | 6,250 | 6,250 | 4 | 0.005 | 16 | 2 |

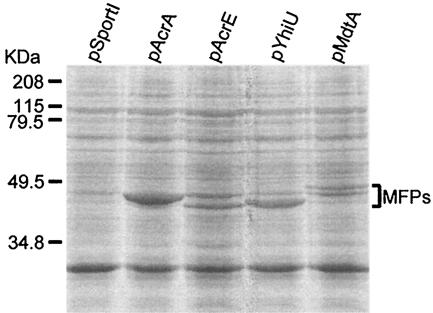

The results shown in Table 2 indicated that AcrE could substitute for AcrA in the activation of (or cooperation with) AcrB but that YhiU or MdtA could not perform this function (see also Table 3). We made certain that all of the E. coli MFPs were expressed in the HNCE3 background (Fig. 1). Membrane extracts of HNCE3 cells overexpressing each MFP gene produced protein bands of approximately 45 kDa. Proteins of this size were absent in extracts from HNCE3(pSportI), as expected from the low levels of expression of the chromosomal acrEF, yhiUV, and mdtABC operons (see above). Interestingly, AcrE and MdtA produced two protein species that were close in size. These species may have resulted from either incomplete lipid modification at the N terminus or cleavage of short segments of the MFP. (The latter was recently proposed to stabilize the tripartite complex in a different system [19].) Finally, the YhiU protein expressed from the clone was functional, because the overexpression of YhiV together with YhiU resulted in strong increases in resistance to bile salts and erythromycin (Table 3).

FIG. 1.

Overexpression of E. coli MFPs in HNCE3 cells induced with 0.1 mM IPTG. Crude membrane extracts were separated in an SDS-10% polyacrylamide gel stained with Coomassie blue.

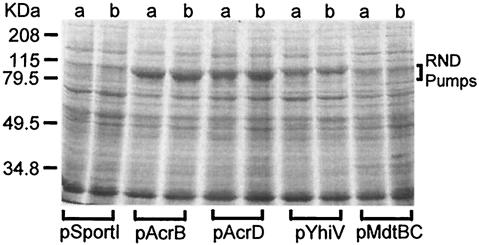

Because of this finding of specificity in the interaction between MFPs and RND pumps, we were also interested in determining whether AcrA, expressed from the chromosomal copy of the acrA gene, could work with other multidrug efflux RND proteins expressed from plasmids. The results are shown in Table 4. AcrA functions with its cognate pump, AcrB, and also with AcrD, as shown in our recent study (7). Interestingly, AcrA increases the efflux of bile salts and dyes by YhiV but does not appear to function with MdtBC. The analysis shown in Table 4, however, relies on the successful overexpression of RND pumps in both acrA+ and ΔacrA strains. We addressed this issue with SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis of membrane extracts from HNCE1a and HNCE1b cells containing plasmids encoding various RND pumps (Fig. 2). Each construct produced a protein band of approximately 110 kDa that was absent in extracts taken from HNCE1a or HNCE1b cells harboring vector pSportI. There was little difference quantitatively between expression in HNCE1a cells and that in HNCElb cells, although each construct expressed the pump protein at its own, different level. Pump expression, therefore, is not the explanation for the difference in resistance between plasmid constructs expressed in HNCE1b cells and those expressed in HNCE1a cells.

TABLE 4.

Ability of AcrA to activate multidrug efflux catalyzed by various E. coli RND transportera

| Drugb | Length of growth zone (mm)c in an acrA+ (+) or a ΔacrA (−) strain with the following construct:

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pSportI

|

pAcrB

|

pAcrD

|

pYhiV

|

pMdtBC

|

||||||

| + | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | |

| Cholic acid | 16 | 17 | 53 | 16 | 36 | 18 | 43 | 19 | 18 | 14 |

| Taurocholic acid | 23 | 22 | 80 | 19 | 80 | 24 | 80 | 20 | 30 | 25 |

| Novobiocin | 0 | 0d | 80 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Crystal violet | 17 | 23 | 80 | 18 | 20 | 25 | 80 | 22 | 20 | 24 |

| Ethidium bromide | 26 | 25 | 80 | 24 | 27 | 25 | 80 | 23 | 24 | 22 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 19 | 20 | 80 | 16 | 19 | 18 | 80 | 23 | 20 | 20 |

| Erythromycin | 45 | 45 | 80 | 40 | 44 | 42 | 80 | 39 | 41 | 40 |

| Tetracycline | 8 | 12 | 80 | 14 | 23 | 14 | 16 | 11 | 12 | 10 |

Growth in the presence of inhibitors was studied by using gradient plates with HNCE1a (acrA+) and HNCE1b (ΔacrA::cat). Because chloramphenicol acetyltransferase, encoded by the cat gene, produces resistance to both chloramphenicol and fusidic acid (7), these two antibiotics were removed from the comparison.

Drug concentrations used were the same as those in Table 2.

See footnote a of Table 2. Values shown in boldface represent cells in which the presence of AcrA significantly increased resistance.

When the lengths of growth zones for pSportI-containing HNCE3 and HNCE1b, both acrA disruption or deletion strains, in Table 2 and Table 4 were compared, differences were seen for some drugs, most notably for novobiocin. This result was partly due to the lack of reproducibility in the preparation of gradient plates; comparisons were valid and were made in this study only between strains streaked on the same plate. This result also may have been due to the function of AcrD, which is present in HNCE3 (used in Table 2) but deleted from HNCE1a and HNCE1b (used in Table 4).

FIG. 2.

Expression of RND proteins from the genome of E. coli in HNCE1a (lanes a) and HNCE1b (lanes b) cells induced with 0.1 mM IPTG. Crude membrane extracts were prepared as described in Materials and Methods and separated in an SDS-7.5% polyacrylamide gel stained with Coomassie blue.

Functions of AcrA-YhiU chimeras.

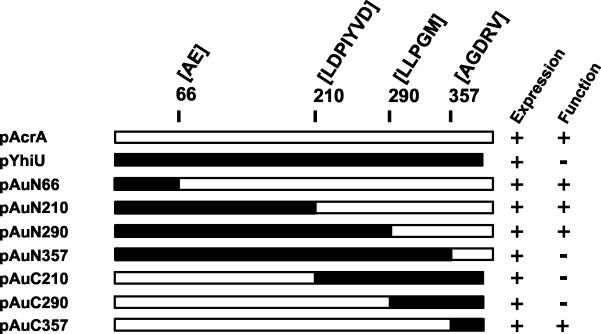

As described above, YhiU cannot function with the AcrB pump. We used this knowledge to create several chimeric mutants of AcrA and YhiU to test the minimum domains of MFP required to function with AcrB. We tried a series of linear fusions in which N-terminal or C-terminal regions of AcrA were replaced with sequences encoding YhiU (Fig. 3). Specific junction sites were chosen based on sequence identity between the two native MFPs. Functional analysis of these chimeras revealed that the N-terminal region of AcrA could be replaced with the corresponding domain of YhiU up to residue 290 and AcrA thus modified could retain the capacity to work together with AcrB or complement resistance in HNCE3, similar to native AcrA (Table 5). After that point, however, the resistance phenotype was lost, as was observed with pAuN357. A complementary experiment was performed by replacing C-terminal portions of AcrA with C-terminal fragments of YhiU and using the same junction sites as those used for the N-terminal chimeras (pAuC series; Fig. 4). In this series, pAuC357, but not pAuC290, could produce a resistance phenotype (Table 5). This result confirmed that the region between residues 290 and 357 plays a decisive role in determining the functional specificity of MFP for the AcrB RND pump. We also attempted to construct a gain-of-function chimera by using plasmid pYhiU, in which this region of yhiU was replaced with that of acrA (pUaR). Unfortunately, this construct was not expressed in HNCE3 cells, and the function of this chimeric protein remains unknown (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Construction of acrA-yhiU chimeras. Precise locations of the fusion junctions between the two MFP genes are indicated in residue numbers and as conserved sequence identities at each junction site. Each construct was assayed for expression (see Fig. 4) and function (see Table 5) in HNCE3 cells.

TABLE 5.

Gradient plate analysis of abilities of chimeric MFPs to support AcrB-catalyzed drug efflux in HNCE3 cells

| Construct | Length of growth zone (mm)a in the presence ofb:

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cholic acid | Taurocholic acid | Fusidic acid | Novobiocin | Crystal violet | Ethidium bromide | Ciprofloxacin | Chloramphenicol | Erythromycin | Tetracycline | |

| pSportI | 37 | 30 | 10 | 19 | 16 | 33 | 43 | 9 | 35 | 20 |

| pAcrA | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 |

| pYhiU | 36 | 38 | 8 | 19 | 17 | 30 | 47 | 5 | 32 | 14 |

| pAuN66 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 |

| pAuN210 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 (38)c | 80 | 80 | 80 |

| pAuN290 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 (35) | 68 | 80 | 80 |

| pAuN357 | 35 | 38 | 10 | 13 | 10 | 36 | 32 | 15 | 35 | 7 |

| pAuC210 | 37 | 30 | 14 | 17 | 15 | 35 | 43 | 7 | 32 | 8 |

| pAuC290 | 40 | 35 | 13 | 17 | 14 | 40 | 40 | 10 | 35 | 11 |

| pAuC357 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 |

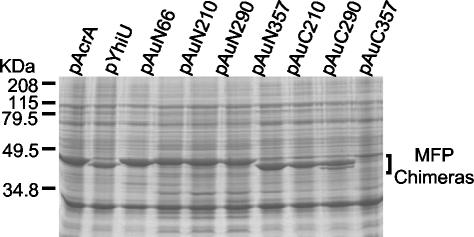

FIG. 4.

Expression of acrA-yhiU chimeric protein products in HNCE3 cells induced with 0.1 mM IPTG. Proteins in crude membrane fractions were separated and visualized as described in the legend to Fig. 1.

All of the chimeric mutants shown in Table 5 could be overexpressed and visualized in membrane extracts of HNCE3 (Fig. 4). Native AcrA and YhiU proteins were slightly different in size (398 and 386 amino acids, respectively). Sequence alignment of the two proteins revealed that this difference resulted from a small truncation at the C terminus of YhiU. This size difference was observed as slight differences in mobility on SDS-polyacrylamide gels (Fig. 1). The chimeric proteins adopted mobilities similar to those of the native proteins from which their respective C-terminal domains were derived, as expected. Thus, all pAuC-series constructs, when expressed, produced faster mobilities, similar to those seen with YhiU, than pAuN-series constructs, a result undoubtedly caused by the difference in size at the C terminus (Fig. 4).

DISCUSSION

The MFP component of the tripartite efflux systems of gram-negative bacteria is often thought to function primarily as a connector or bridge between the outer and the inner membranes (37). This hypothesis is based on several observations. (i) The N terminus of the MFPs is often modified by acylation by fatty acids, as in AcrA (16), or corresponds to a hydrophobic transmembrane helix, as in HlyD (for a review, see reference 12). Thus, the N terminus of MFP is expected to be associated with the inner membrane. (ii) AcrA is an unusually elongated protein, of 10 to 20 nm, as revealed by hydrodynamic studies (35) and electron crystallography (1). This length is probably sufficient to cross the depth of the periplasm. (iii) AcrA was shown in vitro to connect membrane vesicles and to cause hemifusion under acidic conditions (36).

The function of MFP, however, may not be limited to bridging of the membranes. This notion is suggested by the fact that each MFP has a specific preference for a particular transporter. For example, AcrA, but not its homolog, YhiU, works with the transporter AcrB (Table 2). The presence of a physical interaction between AcrA and AcrB is also clear from the chemical cross-linking study performed with intact cells (38). This situation is similar to that in P. aeruginosa, where the MexB pump works together with its cognate MFP, MexA, but not its homolog, MexC (33). The main focus of this study was to localize the domain of the MFP that was responsible for this specific interaction with the RND pump protein, in this case, AcrB. Interestingly, we found that substitution of the first 290 residues (out of the total of 398, i.e., about 75%) of AcrA with the corresponding region of YhiU did not hinder the drug efflux function of the MFP-AcrB complex and hence most likely the interaction of chimeric YhiU-AcrA with AcrB. However, substitution of the following 67 residues of AcrA, between residues 290 and 357, completely abolished the efflux function. The domain crucial for the interaction with AcrB is apparently limited to this region, because substitution of the extreme C-terminal domain of AcrA, between residues 357 and 398, with the YhiU sequence (as in pAuC357) produced a functional protein.

The domain between residues 290 to 357 may play a crucial role because of its effect on the global properties of the protein or, perhaps more interestingly, because of the properties of this localized domain. We first consider the first possibility. The mature AcrA sequence contains 39 negatively charged residues (Asp and Glu) and 38 positively charged residues (Lys and Arg), making the calculated pI 6.18. In contrast, mature YhiU contains 40 negatively charged residues and only 34 positively charged residues, decreasing the calculated pI to 5.12. This net decrease in positively charged residues in YhiU occurs largely in the region between residues 290 and 357. Thus, in this region, AcrA contains eight positively charged and eight negatively charged residues, whereas YhiU contains only five positively charged residues but nine negatively charged residues, with a change in the net charge from 0 to −4. One must keep in mind, therefore, that this region is important in making an MFP a more or less neutral protein.

We now consider the possibility that this region forms a localized domain whose properties are important. AcrA is an elongated protein with a more or less constant width and a length of at least 100 Å, as shown by hydrodynamic studies and by electron crystallography (1, 35). Interestingly, the electron crystallography structure of AcrA contains a large hook-like extrusion rather close to the C terminus (1). The crystallographic structure of AcrB also contains, in its periplasmic domain, a depression in its external surface which was suggested by Murakami et al. (22) as the possible site of interaction with AcrA. It is an attractive hypothesis, at this stage, that this region of AcrA produces a localized domain that interacts with AcrB. Obviously, further biochemical studies are needed in order to test this hypothesis.

One trivial explanation of the effect of AcrA-YhiU chimeras on resistance is that they stabilized, through protein-to-protein interactions, endogenous levels of YhiV, rather than activating AcrB. However, this explanation is unlikely. First, the level of expression of the yhiUV operon is more than 1 order of magnitude lower than that of acrAB, as determined by an RT-PCR assay (see Results). Second, the presence of an unmodified yhiU gene on the multicopy plasmid did not increase resistance to any agents significantly (Tables 2 and 3). Finally, the chimeras increased resistance to tetracycline (Table 5), to which YhiUV could not produce any resistance (Table 3).

The overexpression of YhiUV is known to produce resistance to cationic dyes, erythromycin, and bile salts (25, 26). In this study, we found that the simultaneous overexpression of YhiU and YhiV also gave rise to significant levels of resistance to novobiocin and ciprofloxacin (Table 3); this result may have been due to the difference in the levels of overproduction of these pump components.

It is not known why the pUaR construct was unstable and failed to produce chimeric proteins in membrane extracts of HNCE3 cells. We also constructed a chimera of MdtA that contained the C terminus of AcrA from residue 271, but this chimera was unstable as well (data not shown). This failure may have been due to the low sequence similarity between the two proteins. A similar study of chimeras between P. aeruginosa MFPs MexA and MexC was reported recently (D. Nehme and K. Poole, Abstr. 102nd Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol., abstr. A-133, 2002). In this study also, the chimeras were all unstable proteins, all of which failed to complement drug resistance.

As a preliminary step in the production of chimeras, we studied the functional interactions between the MFPs and transporters of E. coli. A given transporter, AcrB, was found to interact not only with its cognate MFP, AcrA, but also with its closest relative, AcrE. AcrB, however, cannot function with native YhiU or MdtA (Table 2). On the other hand, AcrA appeared to function not only with AcrF (13) but also with most other RND multidrug efflux transporters, with the exception of MdtBC (Table 4). Thus, AcrA can be considered a “universal” MFP, a situation reminiscent of the observations that TolC acts as the universal outer membrane channel in E. coli and that the OprM channel in P. aeruginosa functions with several multidrug efflux systems, including MexAB and MexXY (21), MexCD (10), MexEF (20), and MexJK (4). What gives components such as AcrA, TolC, and OprM such functional flexibility in terms of their interactions is also a topic for future study.

We also assessed the capacity of AcrA to function with an efflux pump of the major facilitator superfamily MFS, EmrB, that also functions as a tripartite complex. As expected, the overexpression of EmrB from plasmids did not increase resistance in HNCE1a cells or in a strain deficient in AcrB and EmrB (results not shown). This outcome was expected, since the structures of the MFS and RND pumps are radically different. RND pumps contain two large periplasmic loops that extend far into the periplasm and can contact TolC directly (22), whereas MFS pumps contain no such extensions. Although EmrA (the cognate MFP for EmrB) and AcrA are phylogenetically related (12) and approximately the same size, EmrA may have a function somewhat different from that of MFP in an RND system.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Public Health Service grant AI-09644 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

We thank Li Zhang for carrying out the RT-PCR experiments and Julio Aires and Xianzhi Li for insightful suggestions during the course of this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Avila-Sakar, A., S. Misaghi, E. Wilson-Kubalek, K. Downing, H. Zgurskaya, H. Nikaido, and E. Nogales. 2001. Lipid-layer crystallization and preliminary three-dimensional structure analysis of AcrA, the periplasmic component of a bacterial multidrug efflux pump. J. Struct. Biol. 136:81-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baranova, N., and H. Nikaido. 2002. The BaeSR two-component regulatory system activates transcription of the yegMNOB (mdtABCD) transporter gene cluster in Escherichia coli and increases its resistance to novobiocin and deoxycholate. J. Bacteriol. 184:4168-4176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bryson, V., and W. Szybalzski. 1952. Microbial selection. Science 116:45-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chuanchuen, R., C. T. Narasaki, and H. P. Schweizer. 2002. The MexJK efflux pump of Pseudomonas aeruginosa requires OprM for antibiotic efflux but not for efflux of triclosan. J. Bacteriol. 184:5036-5044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:6640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dinh, T., I. T. Paulsen, and M. H. Saier, Jr. 1994. A family of extracytoplasmic proteins that allow transport of large molecules across the outer membranes of gram-negative bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 176:3825-3831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elkins, C. A., and H. Nikaido. 2002. Substrate specificity of the RND-type multidrug efflux pumps AcrB and AcrD of Escherichia coli is determined predominantly by two large periplasmic loops. J. Bacteriol. 184:6490-6498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geiser, M., R. Cèbe, D. Drewello, and R. Schmitz. 2001. Integration of PCR fragments at any specific site within cloning vectors without the use of restriction enzymes and DNA ligase. BioTechniques 31:88-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.George, A. M., and S. B. Levy. 1983. Amplifiable resistance to tetracycline, chloramphenicol, and other antibiotics in Escherichia coli: involvement of a non-plasmid-determined efflux of tetracycline. J. Bacteriol. 155:531-540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gotoh, N., H. Tsujimoto, A. Nomura, K. Okamoto, M. Tsuda, and T. Nishino. 1998. Functional replacement of OprJ by OprM in the MexCDOprJ multidrug efflux system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 165:21-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grass, G., and C. Rensing. 2001. Genes involved in copper homeostasis in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183:2145-2147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson, J. M., and G. M. Church. 1999. Alignment and structure prediction of divergent protein families: periplasmic and outer membrane proteins of bacterial efflux pumps. J. Mol. Biol. 287:695-715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kobayashi, K., N. Tsukagoshi, and R. Aono. 2001. Suppression of hypersensitivity of Escherichia coli acrB mutant to organic solvents by integrational activation of the acrEF operon with the IS1 or IS2 element. J. Bacteriol. 183:2646-2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koronakis, V., A. Sharff, E. Koronakis, B. Luisi, and C. Hughes. 2000. Crystal structure of the bacterial membrane protein TolC central to multidrug efflux and protein export. Nature 405:914-919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li, X.-Z., K. Poole, and H. Nikaido. 2003. Contributions of MexAB-OprM and an EmrE homolog to intrinsic resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to aminoglycosides and dyes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:27-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma, D., D. N. Cook, M. Alberti, N. G. Pon, H. Nikaido, and J. E. Hearst. 1993. Molecular cloning and characterization of acrA and acrE genes of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 175:6299-6313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma, D., D. N. Cook, M. Alberti, N. G. Pon, H. Nikaido, and J. E. Hearst. 1995. Genes acrA and acrB encode a stress-induced efflux system of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 16:45-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma, D., D. N. Cook, J. E. Hearst, and H. Nikaido. 1994. Efflux pumps and drug resistance in Gram-negative bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 2:489-493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maseda, H., M. Kitao, S. Eda, E. Yoshihara, and T. Nakae. 2002. A novel assembly process of the multicomponent xenobiotic efflux pump in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Microbiol. 46:677-686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maseda, H., H. Yoneyama, and T. Nakae. 2000. Assignment of the substrate-selective subunits of the MexEF-OprN multidrug efflux pump of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:658-664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Masuda, N., E. Sagagawa, S. Ohya, N. Gotoh, H. Tsujimoto, and T. Nishino. 2000. Contribution of the MexX-MexY-OprM efflux system to intrinsic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2242-2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murakami, S., R. Nakashima, E. Yamashita, and A. Yamaguchi. 2002. Crystal structure of bacterial multidrug efflux transporter AcrB. Nature 419:587-593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagakubo, S., K. Nishino, T. Hirata, and A. Yamaguchi. 2002. The putative response regulator BaeR stimulates multidrug resistance of Escherichia coli via a novel multidrug exporter system, MdtABC. J. Bacteriol. 184:4161-4167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nikaido, H. 1998. Antibiotic resistance caused by gram-negative multidrug efflux pumps. Clin. Infect. Dis. 27:S32-S41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nishino, K., and A. Yamaguchi. 2001. Analysis of a complete library of putative drug transporter genes in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183:5803-5812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nishino, K., and A. Yamaguchi. 2002. EvgA of the two-component signal transduction system modulates production of the YhiUV multidrug transporter in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 184:2319-2323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okusu, H., D. Ma, and H. Nikaido. 1995. AcrAB efflux pump plays a major role in the antibiotic resistance phenotype of Escherichia coli multiple-antibiotic-resistance (Mar) mutants. J. Bacteriol. 178:306-308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paulsen, I. T., J. H. Park, P. S. Choi, and M. H. Saier, Jr. 1997. A family of Gram-negative bacterial outer membrane factors that function in the export of proteins, carbohydrates, drugs, and heavy metals from Gram-negative bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 156:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poole, K. 2001. Multidrug efflux pumps and antimicrobial resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and related organisms. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 3:255-264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosenberg, E. Y., D. Ma, and H. Nikaido. 2000. AcrD of Escherichia coli is an aminoglycoside efflux pump. J. Bacteriol. 182:1754-1756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sulavik, M. C., C. Houseweart, C. Cramer, N. Jiwani, N. Murgolo, J. Greene, B. DiDomenico, K. J. Shaw, G. H. Miller, R. Hare, and G. Shimer. 2001. Antibiotic susceptibility profiles of Escherichia coli strains lacking multidrug efflux pump genes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1126-1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tseng, T., K. S. Gratwick, J. Kollman, D. Park, D. H. Nies, A. Goffau, and M. H. Saier, Jr. 1999. The RND permease superfamily: an ancient, ubiquitous and diverse family that includes human disease and developmental proteins. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1:107-125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yoneyama, H., A. Ocaktan, N. Gotoh, T. Nishino, and T. Nakae. 1998. Subunit swapping in the Mex-extrusion pumps in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 244:898-902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu, E. Y., G. McDermott, H. I. Zgurskaya, H. Nikaido, and D. E. Koshland, Jr. 2003. Structural basis of multiple drug-binding capacity of the AcrB multidrug efflux pump. Science 300:976-980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zgurskaya, H. I., and H. Nikaido. 1999. AcrA is a highly asymmetric protein capable of spanning the periplasm. J. Mol. Biol. 285:409-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zgurskaya, H. I., and H. Nikaido. 1999. Bypassing the periplasm: reconstitution of the AcrAB multidrug efflux pump of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:7190-7195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zgurskaya, H. I., and H. Nikaido. 2000. Multidrug resistance mechanisms: drug efflux across two membranes. Mol. Microbiol. 37:219-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zgurskaya, H. I., and H. Nikaido. 2000. Cross-linked complex between oligomeric periplasmic lipoprotein AcrA and the inner-membrane-associated multidrug efflux pump AcrB from Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 182:4264-4267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]