Abstract

The biosynthetic pathway of medium-chain-length (MCL) polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) from fatty acids has been established in fadB mutant Escherichia coli strain by expressing the MCL-PHA synthase gene. However, the enzymes that are responsible for the generation of (R)-3-hydroxyacyl coenzyme A (R3HA-CoAs), the substrates for PHA synthase, have not been thoroughly elucidated. Escherichia coli MaoC, which is homologous to Pseudomonas aeruginosa (R)-specific enoyl-CoA hydratase (PhaJ1), was identified and found to be important for PHA biosynthesis in a fadB mutant E. coli strain. When the MCL-PHA synthase gene was introduced, the fadB maoC double-mutant E. coli WB108, which is a derivative of E. coli W3110, accumulated 43% less amount of MCL-PHA from fatty acid compared with the fadB mutant E. coli WB101. The PHA biosynthetic capacity could be restored by plasmid-based expression of the maoCEc gene in E. coli WB108. Also, E. coli W3110 possessing fully functional β-oxidation pathway could produce MCL-PHA from fatty acid by the coexpression of the maoCEc gene and the MCL-PHA synthase gene. For the enzymatic analysis, MaoC fused with His6-Tag at its C-terminal was expressed in E. coli and purified. Enzymatic analysis of tagged MaoC showed that MaoC has enoyl-CoA hydratase activity toward crotonyl-CoA. These results suggest that MaoC is a new enoyl-CoA hydratase involved in supplying (R)-3-hydroxyacyl-CoA from the β-oxidation pathway to PHA biosynthetic pathway in the fadB mutant E. coli strain.

Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) are polyesters of (R)-hydroxyalkanoic acids accumulated in numerous bacteria as an energy and carbon storage material under nutrient limiting condition in the presence of excess carbon source (1, 17, 20). PHAs have been attracting much attention as they can be used as biodegradable polymers (20) and as the sources of chiral pools for the synthesis of fine chemicals (18). The metabolic pathways for the biosynthesis and degradation of PHAs have been well examined in many bacteria (17, 20). For example, in short-chain-length-PHA-producing bacteria such as Ralstonia eutropha and Alcaligenes latus, two acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) moieties derived from various carbon sources are condensed to acetoacetyl-CoA by 3-ketothiolase (PhaA) and sequentially converted to (R)-3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA (R3HB-CoA) by acetoacetyl-CoA reductase (PhaB). Then, R3HB-CoA is added to the growing chain of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) [P(3HB)] by the short-chain-length PHA synthase (PhaC) (29).

In pseudomonads belonging to the rRNA homology group I, the intermediates of fatty acid metabolism including enoyl-CoA, (S)-3-hydroxyacyl-CoA, 3-ketoacyl-CoA, and 3-hydroxyacyl-acyl carrier protein (ACP) are major precursors for medium-chain-length (MCL) PHAs (17, 20, 36). The metabolic links between the fatty acid metabolism and PHA biosynthesis are mediated by various enzymes such as enoyl-CoA hydratase (7, 8, 9, 23, 34, 35), 3-ketoacyl-ACP reductase (22, 27, 33), epimerase (20), and 3-hydroxyacyl-ACP:CoA transacylase (12, 26). The genes encoding these enzymes have been cloned from various bacteria and characterized in detail at molecular level. Recently, the MCL-PHA biosynthesis pathway was successfully established in recombinant Escherichia coli by expressing the MCL-PHA synthase gene. The β-oxidation pathway has been engineered by the overexpression of enoyl-CoA hydratase (34, 35) or 3-ketoacyl-ACP reductase (22, 27, 33), and/or by the disruption of FadB or FadA (15, 22, 24, 25, 27). In the former case, the metabolic connection of β-oxidation pathway to PHA biosynthesis is quite clear. However, in the latter case there must exist unidentified enzymes in E. coli which convert β-oxidation intermediates to (R)-3-hydroxyacyl-CoA (R3HA-CoA) when the function of FadB or FadA is disrupted. There has been a report showing that the overexpression of Pseudomonas oleovorans fadBA genes could not establish the PHA biosynthetic pathway in recombinant E. coli (7). Recently, YfcX, which is homologous to FadB, was found to be necessary for the MCL-PHA formation in a fadB mutant E. coli strain (30).

These results encouraged us to search for other missing enzymes linking the β-oxidation pathway and the PHA biosynthetic pathway in the fadB mutant E. coli. Through the E. coli protein sequence database search, MaoC, which is homologous to the P. aeruginosa (R)-specific enoyl-CoA hydratase (PhaJ1) was identified. Results obtained by the inactivation of the chromosomal maoCEc gene in a fadB mutant E. coli strain and enzymatic analysis of MaoC suggested that MaoC is a newly identified enoyl-CoA hydratase, which is involved in linking the β-oxidation and the PHA biosynthetic pathway in the fadB mutant E. coli strain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

The strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. E. coli XL1-Blue (Stratagene Cloning Systems, La Jolla, Calif.) and DH5α (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, Calif.) were used as host strains for general cloning works and gene expression. E. coli W3110, WB101 (W3110 fadB::Km), WB108 (WB101 maoC::Tc), and WB112 (WB101 yfcX::Tc) were used as host strains for the synthesis of MCL-PHAs. The fadB mutant E. coli WB101 was constructed by the insertion of kanamycin resistant gene obtained from pACYC177 (New England Biolabs, Berverly, Mass.) into the middle of fadBEc gene in the E. coli chromosome using pKO3 plasmid (19). The insertional mutation of fadBEc was confirmed by PCR as suggested by Link et al. (19). The fadB maoC mutant E. coli WB108 and the fadB yfcX mutant E. coli WB112 were constructed by replacing the maoCEc gene and the yfcXEc gene in the chromosome of E. coli WB101 with the tetracycline-resistant gene, respectively, using the red operon of bacteriophage λ as described by Jeong and Lee (13). Replacement of the maoCEc gene and the yfcXEc gene with the tetracycline resistant gene was confirmed by PCR.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli strains | ||

| XL1-Blue | recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi hsdR17 suppE44 relA1 λ−lac F′ [proAB lacIqlacZΔM15 Tn10 (Tetr)] | Stratagenea |

| DH5α | supE44 ΔlacU169 (φ80lacZΔM15) hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1 | LTIb |

| W3110 | F− mcrA mcrB IN(rrnD rrnE) 1 λ− | KCTCc |

| WB101 | W3110 (fadB::Km) | This study |

| WB108 | W3110 (fadB::Km maoC::Tc) | This study |

| WB112 | W3110 (fadB::Km yfcX::Tc) | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBBR1MCS | Cmr; cloning vehicle | 14 |

| p10499A | pTrc99A derivative; gntT104 promoter; Apr | 22 |

| pTac99A | pTrc99A derivative; tac promoter; Apr | This study |

| pMCS104613C2 | pBR1MCS derivative; gntT104 promoter, phaC2Ps | This study |

| p10499MaoC | p10499A derivative; maoCEc | This study |

| pTac99MaoCII | pTac99A derivative; maoCEc-His6 tag | This study |

| p10499B2341 | p10499A derivative; yfcXEc | This study |

Stratagene Cloning System.

Invitrogen Life Technologies.

Korean Collection for Type Cultures, Daejeon, Republic of Korea

Plasmid construction.

PCR was performed with the PCR Thermal Cycler MP (Takara Shuzo Co., LTD., Shiga, Japan) using the Expand High Fidelity PCR System (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany). DNA sequencing was carried out using the BigDye Terminator cycle sequencing kit (Perkin-Elmer Co., Boston, Mass.), Taq polymerase, and ABI Prism 377 DNA sequencer (Perkin-Elmer Co.). All DNA manipulations including restriction digestion, ligation, and agarose gel electrophoresis were carried out by standard procedures (28).

Plasmids and primers used in this study are listed in Table 1 and 2, respectively. Plasmid pMCS104613C2 was constructed by the insertion of EcoRV-SspI digested gene fragment of p10499613C2 (22) containing the gntT104 promoter and the Pseudomonas sp. strain 61-3 phaC2Ps gene (21) into EcoRV-digested pBBR1MCS (14).

TABLE 2.

Primers used in PCR exprimentsa

| Primer no. | Sequence | Gene |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5′-TTTCCCGAGCTCATGCAGCAGTTAGCCAGTTTC | maoCEc |

| 2 | 5′-GCTCTAGATTAATCGACAAAATCACCGTG | maoCEc |

| 3 | 5′-TTTCCCGAGCTCATGCAGCAGTTAGCCAGTTTC | maoCEc-His6 tag |

| 4 | 5′-GCTCTAGATTAATGGTGATGATGGTGATGATCGACAAAATCACCGTG | maoCEc-His6 tag |

| 5 | 5′-GGAATTCATGGAAATGACATCAGCGTTTACC | yfeXEc |

| 6 | 5′-CCCAAGCTTTTATTGCAGGTCAGTTGC | yfcXEc |

Restriction enzyme sites are shown in boldface type. The template for all primers was the E. coli W3110 chromosome.

Primers for the amplification of the maoCEc and yfcXEc genes were designed based on the reported E. coli genome sequence (3). A plasmid for the expression of the E. coli maoCEc gene was constructed by the insertion of the PCR amplified maoCEc gene at SacI and XbaI sites of plasmid p10499A (22). Also, PCR amplified yfcXEc gene was inserted into p10499A at EcoRI and HindIII sites. pTac99A is a derivative of pTrc99A (Pharmacia Biotech., Uppsala, Sweden), which was constructed by replacing the trc promoter of pTrc99A with the tac promoter from pKK223-3 (Pharmacia Biotech) digested by PvuII and EcoRI. pTac99MaoCH was constructed by the insertion of PCR amplified maoCEc gene fused with His6-Tag at its C-terminal (maoCEc-his6-tag) into pTac99A at the SacI and XbaI sites.

Culture conditions.

E. coli XL1-Blue and DH5α were cultured at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (containing, per liter, 10 g of tryptone, 5 g of yeast extract, and 5 g of NaCl). For the biosynthesis of PHA, recombinant E. coli W3110, WB101, WB108, and WB112 strains were cultivated for 96 h in 250-ml flasks containing 100 ml of LB medium supplemented with sodium decanoate (2 g/liter; Sigma Co., St. Louis, Mo.). Flask cultures were carried out in a rotary shaker at 250 rpm and 30°C. Ampicillin (50 mg/liter) and chloramphenicol (34 mg/liter) were added to the medium.

Analytical procedures.

PHA concentration and monomer composition were determined by gas chromatography (Donam Co., Seoul, Korea) equipped with a fused silica capillary column (SPB-5 film [30 m by 0.32 mm; inner diameter, 0.25 μm]; Supelco, Bellefonte, Pa.) using benzoic acid as an internal standard (4). Cell concentration, defined as dry cell weight (DCW) per liter of culture broth, was determined as previously described (6, 16). The residual cell concentration was defined as the cell concentration minus PHA concentration. The PHA content (weight percent) was defined as the percentage of the ratio of PHA concentration to cell concentration.

Protein expression and activity measurement.

The maoCEc-his6-tag gene was expressed by inducing with 1 mM IPTG in recombinant E. coli DH5α (pTac99MaoCH). The protein level was analyzed by electrophoresis on a 12% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel (SDS-PAGE). Crude extracts of recombinant E. coli strains were prepared by three cycles of sonication (each for 20 s at 15% of maximum output; High-Intensity Ultrasonic Liquid Processors; Sonics & Material Inc., Newtown, Conn.). MaoCEc-His6-Tag was purified by Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid spin column kit (Qiagen Inc, Valencia, Calif.). The amount of soluble proteins was determined by Bio-Rad protein assay kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) using bovine serum albumin as a standard.

The enoyl-CoA hydratase activity was measured by assaying the hydration of crotonyl-CoA (Sigma Co.) at 263 nm (DU series 600 spectrophotometer; Beckman, Fullerton, Calif.) (2, 8, 30). A 10-μl aliquot of enzyme solution was added to 90 μl of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) containing 0.25 mM crotonyl-CoA. The decrease in absorbance at 263 nm was measured. The extinction coefficient (ɛ263) of the enoyl-thioester bond is 6.7 × 103 M−1 cm−1 (2). One unit of enoyl-CoA hydratase activity was defined as the removal of 1 μmol of crotonyl-CoA per min. The specific activity of enoyl-CoA hydratase was defined as the activity of enoyl-CoA hydratase per milligram of protein.

RESULTS

Identification of the E. coli gene homologous to P. aeruginosa phaJ1Pa.

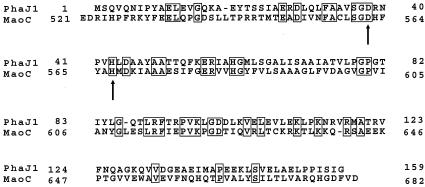

The E. coli maoCEc gene was found to be homologous to the P. aeruginosa phaJ1Pa gene by BLAST search (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/). From the conserved domain database, PhaJ1 was found to have the MaoC like domain. The amino acid sequence of MaoC showed 34% identity to that of PhaJ1 (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Alignment of the deduced amino acid sequence of E. coli MaoC with that of P. aeruginosa (R)-specific enoyl-CoA hydratase (PhaJ1). Conserved amino acids are shown in boxes. The catalytically important residues Asp and His are indicated by arrows.

Production of PHA in recombinant E. coli strains harboring the MCL-PHA synthase gene and the maoCEc gene.

Recombinant E. coli W3110 harboring only the Pseudomonas sp. 61-3 phaC2Ps gene did not produce PHA from sodium decanoate (22). Also, coexpression of the yfcXEc and phaC2Ps genes in E. coli W3110 did not result in the accumulation of PHA from sodium decanoate (Table 3). On the other hand, the coexpression of the yfcXEc and phaC2Ps genes in E. coli WB101 resulted in the accumulation of PHA up to 0.39 g/liter, which is higher than that obtained with E. coli WB101 harboring the phaC2Ps gene only (0.21 g/liter). The fadB yfcX mutant E. coli WB112 showed decreased PHA biosynthetic activity as previously reported by Snell et al. (30). The restoration of PHA biosynthetic activity of E. coli WB112 was achieved by the plasmid-based expression of the yfcXEc gene (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Results of flask cultures of recombinant E. coli strains harboring different sets of plasmidsa

| Strain | Condition | DCW (g/liter) | PHA concn (g/liter) | PHA content (wt %) | Monomer composition (mol%)b

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3HB | 3HHx | 3HO | 3HD | |||||

| W3110 | pMCS104613C2 + p10499A | 1.50 ± 0.01 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| W3110 | pMCS104613C2 + p10499B2341 | 1.20 ± 0.04 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| W3110 | pMCS104613C2 + p10499MaoC | 1.95 ± 0.02 | 0.23 ± 0.04 | 11.9 ± 2.0 | 0 | 19 ± 2 | 74 ± 2 | 7 ± 2 |

| WB101 | pMCS104613C2 + p10499A | 0.97 ± 0.01 | 0.21 ± 0.01 | 21.0 ± 1.4 | 0 | 9 ± 2 | 37 ± 2 | 54 ± 2 |

| WB101 | pMCS104613C2 + p10499MaoC | 1.00 ± 0.03 | 0.20 ± 0.01 | 20.0 ± 1.6 | 0 | 0 | 61 ± 2 | 39 ± 2 |

| WB101 | pMCS104613C2 + p10499B2341 | 1.13 ± 0.02 | 0.39 ± 0.05 | 34.5 ± 3.5 | 0 | 9 ± 2 | 33 ± 2 | 58 ± 2 |

| WB112 | pMCS104613C2 + p10499A | 0.80 ± 0.01 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 6.3 ± 1.1 | 0 | 8 ± 2 | 36 ± 2 | 56 ± 2 |

| WB112 | pMCS104613C2 + p10499B2341 | 1.15 ± 0.01 | 0.30 ± 0.02 | 26.0 ± 1.9 | 0 | 10 ± 2 | 34 ± 2 | 56 ± 2 |

| WB108 | pMCS104613C2 + p10499A | 0.78 ± 0.01 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 15.0 ± 1.8 | 0 | 9 ± 2 | 52 ± 2 | 37 ± 2 |

| WB108 | pMCS104613C2 + p10499MaoC | 0.80 ± 0.01 | 0.16 ± 0.01 | 20.0 ± 1.3 | 0 | 0 | 61 ± 2 | 39 ± 2 |

Cells were cultivated for 96 h at 30°C in LB medium supplemented with sodium decanoate (2 g/liter). All experiments were carried out in triplicate.

Abbreviations: 3HB, (R)-3-hydroxybutyrate; 3HHx, (R)-3-hydroxyhexanoate; 3HO, (R)-3-hydroxyoctanoate; 3HD, (R)-3-hydroxydecanoate.

To examine whether the maoCEc gene can supply R3HA-CoAs from the β-oxidation pathway, recombinant E. coli strains W3110 and WB101 harboring pMCS104613C2 and p10499MaoC were cultivated in LB medium containing sodium decanoate (2 g/liter) at 30°C. When the maoCEc gene was coexpressed with the phaC2Ps gene in recombinant E. coli W3110, MCL-PHA consisting of 3-hydroxyhexanoate (3HHx), 3-hydroxyoctanoate (3HO) and 3-hydroxydecanoate (3HD) was produced up to 12 wt% of DCW from sodium decanoate. It is interesting that 3-hydroxybutyrate (3HB) was not incorporated into PHA even though the Pseudomonas sp. strain 61-3 PHA synthase has been shown to be able to incorporate 3HB monomer (21). The mole fraction of 3HO was the highest (Table 3).

Recombinant E. coli WB101 harboring only the phaC2Ps gene accumulated PHA consisting of 3HHx, 3HO, and 3HD from sodium decanoate as previously reported by Steinbüchel's group (15, 25). The coexpression of the maoCEc gene resulted in the incorporation of more 3HO monomer (up to 61 mol%) into PHA without much increase of the PHA content and PHA concentration. It is notable that the 3HHx monomer was not incorporated into PHA when the maoCEc gene was additionally expressed (Table 3).

Construction of fadB and maoC mutant E. coli and its use for PHA biosynthesis.

In order to confirm the possible role of MaoC linking the β-oxidation and PHA biosynthetic pathways, a fadB maoC double-mutant strain WB108 was constructed. When the recombinant E. coli WB108 harboring only the phaC2Ps gene was cultured from sodium decanoate, the PHA concentration obtained was only a half of that obtained with recombinant E. coli WB101, which means that one of the metabolic links between the β-oxidation and PHA biosynthetic pathways is disconnected by the inactivation of MaoC (Table 3). Restoration of the MaoC activity by the introduction of p10499MaoC allowed recombinant E. coli WB108 harboring the phaC2Ps gene to synthesize PHA consisting of 3HO and 3HD from sodium decanoate, which is similar to that obtained with WB101 harboring pMCS104613C2 and p10499MaoC (Table 3).

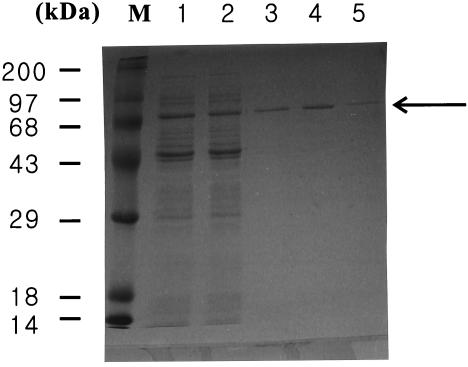

Enoyl-CoA hydratase activity of MaoC.

The MaoCEc-His6-Tag protein was produced using E. coli DH5α (pTac99MaoCH) and purified (Fig. 2). This tagged MaoC was used to examine enoyl-CoA hydratase activity using crotonyl-CoA as the substrate. The purified tagged MaoC showed the enoyl-CoA hydratase activity of 47.6 U/mg towards crotonyl-CoA.

FIG. 2.

SDS-PAGE analysis of MaoCEc-His6-Tag in recombinant E. coli DH5α (pTac99MaoCH). Lane M, molecular mass standard; lane 1, total proteins from E. coli DH5α (pTac99MaoCH) after induction; lane 2, total proteins obtained by sonication of E. coli DH5α (pTac99MaoCH); lanes 3 to 5, proteins obtained after the first, second, and third elutions, respectively, from the Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid column. MaoCEc-His6-Tag is indicated by solid arrow. MaoCEc-His6-Tag obtained after the second elution was used for assaying the enoyl-CoA hydratase activity.

DISCUSSION

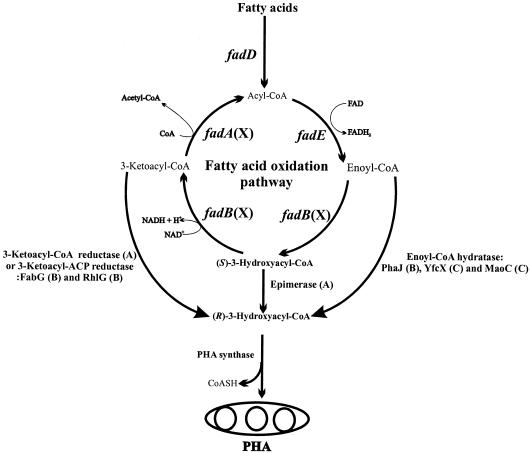

It has previously been demonstrated that recombinant E. coli impaired in β-oxidation pathway successfully synthesizes MCL-PHAs from fatty acids when equipped with a functional MCL-PHA synthase (15, 22, 24, 25, 27). The elucidated metabolic pathways for the production of MCL-PHA from the intermediates of β-oxidation pathway are shown in Fig. 3. Various enzymes including FadD, FadE, enoyl-CoA hydratase, epimerase and 3-ketoacyl-CoA reductase are involved in the generation of R3HA-CoAs, the substrates for PHA synthase, from fatty acid (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Proposed metabolic pathways for PHA biosynthesis in recombinant E. coli strain from fatty acid through β-oxidation pathway. Enoyl-CoA hydratase, epimerase and 3-ketoacyl-CoA or ACP reductase have been employed to supply PHA precursors. The following letters in parentheses represent the indicated enzymes: A, enzymes that have not been elucidated in E. coli; B, amplified enzymes to supply PHA precursors FabG (22, 27, 33), RhlG (22), and PhaJ (9, 23, 34, 35); C, enzymes that are activated when the FadB is inactivated − YfcX (30), MaoC (this study); X, enzymes that should be inactivated to supply PHA precursors from fatty acid (15, 22, 24, 25, 27, 30).

It has been shown that the generation of R3HA-CoAs is possible only when the multienzyme complex FadAB is partially or fully inactivated. The enzymes responsible for connecting the β-oxidation and the PHA biosynthetic pathways in E. coli have not been thoroughly elucidated yet. Only recently, YfcX, which is homologous to FadB, has been suggested to be responsible for supplying MCL-PHA precursors from the β-oxidation pathway when FadB activity is removed in recombinant E. coli (30). We, therefore examined whether the overexpression of the yfcXEc gene can establish PHA biosynthetic pathway in E. coli W3110 harboring the Pseudomonas sp. strain 61-3 MCL-PHA synthase gene. However, PHA was not accumulated from sodium decanoate (Table 3). Also, there has been a report showing that the overexpression of the P. oleovorans fadBA genes did not support PHA biosynthesis in recombinant E. coli (7). The effect of coexpressing the yfcXEc gene was notable in a fadB mutant E. coli WB101, resulting in the increase of PHA concentration compared with that obtained in E. coli WB101 harboring the phaC2Ps gene only (Table 3).

In bacteria synthesizing PHA from fatty acids, such as pseudomonads and aeromonads, the β-oxidation and PHA biosynthetic pathways is known to be linked by (R)-specific enoyl-CoA hydratases having broad substrate specificities even though they also possess FadB containing enoyl-CoA hydratase activity (7, 8, 9, 23, 34, 35). These results encouraged us to search for a missing enzyme in E. coli, which is responsible for linking the β-oxidation and PHA biosynthetic pathways.

Protein database search revealed that a putative aldehyde dehydrogenase, MaoC, is homologous to the P. aeruginosa enoyl-CoA hydratase (PhaJ1). The maoC gene exists as an operon with the maoA gene in E. coli (31, 32). The mao operon has been reported to encode enzymes involved in the degradation of aromatic amine compounds. The maoA gene encodes an aromatic amine oxidase, which is similar to that of Klebsiella aerogenes (31, 32). Until now, the enzymatic characterization of E. coli MaoC has not been carried out. We, therefore, examined whether this uncharacterized enzyme, MaoC, can link the β-oxidation and PHA biosynthetic pathways in E. coli.

When the (R)-specific enoyl-CoA hydratase and the 3-ketoacyl-ACP reductase from various bacteria were used for the establishment of the PHA biosynthetic pathway in E. coli, the high level expression of these enzymes was suggested to be important for efficient channeling of PHA precursors from the β-oxidation pathway to the PHA biosynthetic pathway (9). Therefore, it was first examined whether the overexpression of the maoC gene could supply PHA precursors from fatty acid. As summarized in Table 3, the coexpression of the maoCEc and phaC2Ps genes in E. coli W3110 successfully allowed MCL-PHA accumulation. Considering that E. coli W3110 harboring only the PHA synthase did not produce PHA from fatty acid, it can be concluded that the overexpression of the maoC gene is necessary for channeling PHA precursors from the β-oxidation pathway. These results also suggest that E. coli MaoC carries out hydration of enoyl-CoAs to make R3HA-CoAs because the PHA synthase accepts only the (R)-form hydroxyacyl-CoAs as substrates.

Recently, another β-oxidation pathway operating under anaerobic conditions using nitrate as a terminal respiratory electron acceptor, which is composed of YfcYX, was found to exist besides aerobic β-oxidation pathway in E. coli (5). Also, it was reported that the deletion of the yfcX gene in fadB mutant E. coli abolished PHA biosynthetic capacity (30). When the fadA and/or fadB genes are deleted, other enzymes such as YfcYX, which are able to use the β-oxidation cycle intermediates as substrates, seem to functionally operate. This phenomenon has been reported by several groups, who showed that various fadA and/or fadB mutant E. coli strains efficiently synthesized MCL-PHAs when a heterologous MCL-PHA synthase gene was introduced (15, 22, 24, 25, 27). A fadB mutant E. coli strain WB101 used in this study synthesized PHA when the Pseudomonas sp. strain 61-3 PHA synthase gene was introduced. Since enoyl-CoAs must be converted to R3HA-CoAs in E. coli, it was reasoned that E. coli may possess another enzyme having enoyl-CoA hydratase activity besides FadB. And, in this study, we have shown by gene knockout study and by enzyme assay that MaoC is the enzyme possessing enoyl-CoA hydratase activity in fadB mutant E. coli. From the results that the deletion of maoCEc gene did not thoroughly abolish the PHA biosynthetic capacity, there should be other enzymes such as YfcX connecting the β-oxidation and PHA biosynthetic pathways. Haller et al. (10) reported that several enzymes including YfcX, PaaF, PaaG, and YgfG comprise crotonase superfamily, which are highly homologous to FadB and share the same active site with that of FadB. These enzymes may provide possible routes connecting the β-oxidation and PHA biosynthetic pathways. As shown in Table 3, MCL-PHA consisting of various monomers, of which carbon numbers were reduced by 2 and 4 compared with those of supplied fatty acid, was produced by fadB mutant E. coli, even though the key enzyme, FadB, involved in cycling intermediates of β-oxidation was inactivated. These results might have resulted from the presence of various FadB homologous enzymes mentioned above.

Recently, the crystal structure of Aeromonas caviae (R)-specific enoyl-CoA hydratase was resolved, and the catalytic residues were suggested to be Asp-31 and His-36 (11). Also, these amino acids were found to be highly conserved in various (R)-hydratases (11). Multiple alignment of MaoC and PhaJ1 clearly showed that these essential amino acid residues also exist in MaoC at conserved region (Fig. 1) supporting that MaoC is a new enoyl-CoA hydratase in E. coli.

Until now, the missing link between the PHA biosynthetic pathway and the β-oxidation pathway has not been thoroughly elucidated in recombinant E. coli. In this study, we have shown that MaoC is a new enoyl-CoA hydratase which is involved in converting enoyl-CoAs to R3HA-CoAs in fadB mutant E. coli. When the host strain possesses intact FadB, MaoC was not able to convert as much enoyl-CoAs as in the fadB mutant strain (Table 3), suggesting that FadB has higher affinity and activity towards enoyl-CoAs. From these results, the metabolic pathway for PHA biosynthesis using impaired β-oxidation pathway in recombinant E. coli is suggested (Fig. 3).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Research Laboratory Program (2000-N-NL-01-C-237) of the Ministry of Science and Technology, the Center for Ultramicrochemical Process Systems sponsored by KOSEF, and the BK21 project. Hardware support for computational analysis by the IBM-SUR program is greatly appreciated.

We thank Y. Doi (RIKEN, Saitana, Japan) and Isabelle-S. Hinner (GBF, Braunschweig, Germany) for kindly providing us with plasmids pBSEB50 and pBBR1MCS, respectively. We also thank G. M. Church (Harvard Medical School) for the kind gift of plasmid pKO3.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson, A., and E. A. Dawes. 1990. Occurrence, metabolism, metabolic role, and industrial uses of bacterial polyhydroxyalkanoates. Microbiol. Rev. 54:450-472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Binstock, J. F., and H. Schulz. 1981. Fatty acid oxidation complexes from Escherichia coli. Methods Enzymol. 71:403-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blattner, F. R., G. Plunkett, C. A. Bloch, N. T. Perna, V. Burland, M. Riley, J. Collado-Vides, J. D. Glasner, K. Rode, G. F. Mayhew, J. Gregor, N. W. Davis, H. A. Kirkpatrick, M. A. Goeden, D. J. Rose, B. Mau, and Y. Shao. 1997. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science 277:1453-1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braunegg, G., B. Sonnleitner, and R. M. Lafferty. 1978. A rapid gas chromatographic method for the determination of poly-β-hydroxybutyric acid in microbial biomass. Eur. J. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 6:29-37. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell, J. W., R. M. Morgan-Kiss, and J. E. Cronan, Jr. 2003. A new Escherichia coli metabolic competency: growth on fatty acids by a novel anaerobic β-oxidation pathway. Mol. Microbiol. 47:793-805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi, J., S. Y. Lee, K. Shin, W. G. Lee, S. J. Park, H. N. Chang, and Y. K. Chang. 2002. Pilot scale production of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) by fed-batch culture of recombinant Escherichia coli. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 7:371-374. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fiedler, S., A. Steinbüchel, and B. H. A. Rehm. 2002. The role of the fatty acid beta-oxidation multienzyme complex from Pseudomonas oleovorans in polyhydroxyalkanoate biosynthesis: molecular characterization of the fadBA operon from P. oleovorans and of the enoyl-CoA hydratase genes phaJ from P. oleovorans and Pseudomonas putida. Arch. Microbiol. 178:149-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fukui, T., N. Shiomi, and Y. Doi. 1998. Expression and characterization of (R)-specific enoyl coenzyme A hydratase involved in polyhydroxyalkanoate biosynthesis by Aeromonas caviae. J. Bacteriol. 180:667-673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fukui, T., S. Yokomizo, G. Kobayashi, and Y. Doi. 1999. Co-expression of polyhydroxyalkanoate synthase and (R)-enoyl-CoA hydratase genes of Aeromonas caviae establishes copolyester biosynthesis pathway in Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 170:69-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haller, T., T. Buckel, J. Retey, and J. A. Gerlt. 2000. Discovering new enzymes and metabolic pathways: conversion of succinate to propionate by Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 39:4622-4629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hisano, T., T. Tsuge, T. Fukui, T. Iwata, K. Miki, and Y. Doi. 2003. Crystal structure of the (R)-specific enoyl-CoA hydratase from Aeromonas caviae involved in polyhydroxyalkanoate biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 278:617-624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoffmann, N., A. Steinbüchel, B. H. A. Rehm. 2000. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa phaG gene product is involved in the synthesis of polyhydroxyalkanoic acid consisting of medium-chain-length constituents from non-related carbon sources. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 184:253-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeong, K. J., and S. Y. Lee. 2002. Excretion of human β-endorphin into culture medium by using outer membrane protein F as a fusion partner in recombinant Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:4979-4985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kovach, M. E., P. H. Elzer, D. S. Hill, G. T. Robertson, M. A. Farris, R. M. Roop II, and K. M. Peterson. 1995. Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene 166:175-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Langenbach, S., B. H. A. Rehm, and A. Steinbüchel. 1997. Functional expression of the PHA synthase gene phaC1 from Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Escherichia coli results in poly(3-hydroxyalkanoate) synthesis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 150:303-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee, S. H., D. H. Oh, W. S. Ahn, Y. Lee, J. Choi, and S. Y. Lee. 2000. Production of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) by high-cell-density cultivation of Aeromonas hydrophila. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 67:240-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee, S. Y. 1996. Bacterial polyhydroxyalkanoates. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 49:1-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee, S. Y., S. H. Park, Y. Lee, and S. H. Lee. 2001. Production of chiral and other valuable compounds from microbial polyesters, p. 375-388. In Y. Doi and A. Steinbüchel (ed.), Biopolymers, vol. 4. Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, Germany.

- 19.Link, A. J., D. Phillips, and G. M. Church. 1997. Methods for generating precise deletions and insertions in the genome of wild-type Escherichia coli: application to open reading frame characterization. J. Bacteriol. 179:6228-6237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Madison, L. L., and G. W. Huisman. 1999. Metabolic engineering of poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates): from DNA to plastic. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63:21-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsusaki, H., S. Manji, K. Taguchi, M. Kato, T. Fukui, and Y. Doi. 1998. Cloning and molecular analysis of the poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) and poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyalkanoate) biosynthesis genes in Pseudomonas sp. strain 61-3. J. Bacteriol. 180:6459-6467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park, S. J., J. P. Park, and S. Y. Lee. 2002. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for the production of medium-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoates rich in specific monomers. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 214:217-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park, S. J., W. S. Ahn, P. R. Green, and S. Y. Lee. 2001. Production of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) by metabolically engineered Escherichia coli strains. Biomacromolecules 2:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qi, Q., A. Steinbüchel, and B. H. A. Rehm. 1998. Metabolic routing towards polyhydroxyalkanoic acid synthesis in recombinant Escherichia coli (fadR): inhibition of fatty acid beta-oxidation by acrylic acid. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 167:89-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qi, Q., B. H. A. Rehm, and A. Steinbüchel. 1997. Synthesis of poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates) in Escherichia coli expressing the PHA synthase gene phaC2 from Pseudomonas aeruginosa: comparison of PhaC1 and PhaC2. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 157:155-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rehm, B. H. A., N. Kruger, and A. Steinbüchel. 1998. A new metabolic link between fatty acid de novo synthesis and polyhydroxyalkanoic acid synthesis. The phaG gene from Pseudomonas putida KT2440 encodes a 3-hydroxyacyl-acyl carrier protein-coenzyme a transferase. J. Biol. Chem. 273:24044-24051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ren, Q., N. Sierro, B. Witholt, and B. Kessler. 2000. FabG, an NADPH-dependent 3-ketoacyl reductase of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, provides precursors for medium-chain-length poly-3-hydroxyalkanoate biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 182:2978-2981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 29.Schubert, P., A. Steinbüchel, and H. G. Schlegel. 1988. Cloning of the Alcaligenes eutrophus genes for synthesis of poly-beta-hydroxybutyric acid (PHB) and synthesis of PHB in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 170:5837-5847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Snell, K. D., F. Feng, L. Zhong, D. Martin, and L. L. Madison. 2002. YfcX enables medium-chain-length poly(3-hydroxyalkanoate) formation from fatty acids in recombinant Escherichia coli fadB strains. J. Bacteriol. 184:5696-5705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steinebach, V., J. A. E. Benen, R. Bader, P. W. Postma, S. De Vries, and J. A. Duine. 1996. Cloning of the maoA gene that encodes aromatic amine oxidase of Escherichia coli W3350 and characterization of the overexpressed enzyme. Eur. J. Biochem. 237:584-591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sugino, H., M. Sasaki, H. Azakami, M. Yamashita, and Y. Murooka. 1992. A monoamine-regulated Klebsiella aerogenes operon containing the monoamine oxidase structural gene (maoA) and the maoC gene. J. Bacteriol. 174:2485-2492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taguchi, K., Y. Aoyagi, H. Matsusaki, T. Fukui, and Y. Doi. 1999. Co-expression of 3-ketoacyl-ACP reductase and polyhydroxyalkanoate synthase genes induces PHA production in Escherichia coli HB101 strain. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 176:183-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsuge, T., T. Fukui, H. Matsusaki, S. Taguchi, G. Kobayashi, A. Ishizaki, and Y. Doi. 2000. Molecular cloning of two (R)-specific enoyl-CoA hydratase genes from Pseudomonas aeruginosa and their use for polyhydroxyalkanoate synthesis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 184:193-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsuge, T., K. Taguchi, S. Taguchi, and Y. Doi. 2003. Molecular characterization and properties of (R)-specific enoyl-CoA hydratases from Pseudomonas aeruginosa: metabolic tools for synthesis of polyhydroxyalkanoates via fatty acid β-oxidation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 31:195-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Witholt, B., and B. Kessler. 1999. Perspectives of medium chain length poly(hydroxyalkanoates), a versatile set of bacteral bioplastics. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 10:279-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]