Abstract

Twelve isolates of Enterobacteriaceae (1 of Klebsiella pneumoniae, 8 of Escherichia coli, 1 of Proteus mirabilis, and 2 of Proteus vulgaris) classified as extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) producers according to the ESBL screen flow application of the BD-Phoenix automatic system and for which the cefotaxime MICs were higher than those of ceftazidime were collected between January 2001 and July 2002 at the Laboratory of Clinical Microbiology of the San Matteo University Hospital of Pavia (northern Italy). By PCR and sequencing, a CTX-M-type determinant was detected in six isolates, including three of E. coli (carrying blaCTX-M-1), two of P. vulgaris (carrying blaCTX-M-2), and one of K. pneumoniae (carrying blaCTX-M-15). The three CTX-M-1-producing E. coli isolates were from different wards, and genotyping by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) revealed that they were clonally unrelated to each other. The two CTX-M-2-producing P. vulgaris isolates were from the same ward (although isolated several months apart), and PFGE analysis revealed probable clonal relatedness. The blaCTX-M-1 and blaCTX-M-2 determinants were transferable to E. coli by conjugation, while conjugative transfer of the blaCTX-M-15 determinant from K. pneumoniae was not detectable. Present findings indicate that CTX-M enzymes of various types are present also in Italy and underscore that different CTX-M determinants can be found in a single hospital and can show different dissemination patterns. This is also the first report of CTX-M-2 in P. vulgaris.

The CTX-M-type enzymes are a group of molecular class A extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) that exhibit an overall preference for cefotaxime (CTX; hence the CTX-M name) and ceftriaxone and a higher susceptibility to tazobactam than to clavulanate. These enzymes are emerging in members of the family Enterobacteriaceae, where they can cause resistance to CTX and other expanded-spectrum β-lactams (7, 28).

Several different variants of CTX-M-type enzymes have been identified to date. They are clustered in at least six major evolutionary lineages (CTX-M-1, CTX-M-2, CTX-M-8, CTX-M-9, CTX-M-25, and Toho-2), named after the enzyme first discovered for each lineage (5; amino acid sequences for TEM, SHV, and OXA extended-spectrum and inhibitor-resistant β-lactamases are found at http://www.lahey.org/studies/webt.stm). Members of different lineages differ at 10 to 30% of the amino acid residues, while most lineages include a number of minor variants that may differ from each other by one or a few amino acid substitutions (http://www.lahey.org/studies/webt.stm). Members of the CTX-M-2 and CTX-M-8 lineages are most likely derived from the mobilization of chromosomal β-lactamase genes of Kluyvera ascorbata and Kluyvera georgiana, respectively (12, 20), while the original sources of the other enzymes of this group remain unknown. Enzymes closely related to the CTX-M group include the chromosomal β-lactamases of Klebsiella oxytoca, Proteus vulgaris, Citrobacter diversus, Serratia fonticola, and Kluyvera cryocrescens (7, 9).

The blaCTX-M genes are often carried on transferable plasmids (28). Two of them (blaCTX-M-2 and blaCTX-M-9) were found to be associated with complex class 1 integrons related to In6 and In7, although they are not found on typical gene cassettes (1, 10, 23).

The CTX-M-type enzymes were first reported in South America (M. Radice, P. Power, J. Di Conza, and G. Gutkind, Letter, Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:602-603, 2002), Germany (4), and France (3). Subsequently reports showed that they are present in several European countries (2, 6, 7, 11, 24; I. Alobwede, F. H. M'Zali, D. M. Livermore, J. Heritage, N. Todd, and P. M. Hawkey, Letter, J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 51:471-473, 2003), as well as in the Far East (7, 8, 29, 30), India (14), Russia (M. Pimkin, M. Edelstein, I. Palagin, A. Narezkina, and L. Stratchounski, Abstr. 42nd Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. C2-1874, 2002) and North America (E. S. Moland, S. Pottumarthy-Boddu, J. A. Black, A. Hossain, N. D. Hanson, and K. S. Thomson, Abstr. 42nd Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. LB-13, 2002).

In this work we report on the first detection of different CTX-M-type enzymes (CTX-M-1, CTX-M-2, and CTX-M-15) in clinical isolates of Enterobacteriaceae, including Escherichia coli, P. vulgaris, and Klebsiella pneumoniae, from an Italian hospital. We also report on the first detection of CTX-M-2 in P. vulgaris.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Bacterial strains analyzed in this study included 12 clinical isolates of Enterobacteriaceae, each from a different patient, that upon susceptibility testing with the NMIC/ID 4 panel of BD-Phoenix (BD Diagnostic Systems Europe, Le Pont de Claix, France) were classified as ESBL producers by the ESBL screen flow application of the same system. The CTX MICs for these isolates were found to be higher than those of ceftazidime (CAZ) in conventional microdilution susceptibility testing. The 12 isolates were from inpatients at the San Matteo IRCCS Hospital of Pavia (northern Italy) during the period January 2001 to July 2002 and were identified with the GNID panel of BD-Phoenix. For P. vulgaris isolates, the identification was confirmed by the GNI card of the Vitek system (BioMérieux, Rome, Italy) and by the API 20E identification system (BioMérieux).

Susceptibility testing.

MICs of CTX, CAZ, cefepime (FEP), and aztreonam (ATM) were determined by a microdilution test using cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton (MH) broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.), in accordance with the criteria of the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (15). The MIC panels were prepared in house. Plates were incubated at 35°C for 18 h before recording results. E. coli ATCC 25922 was used as a reference strain for quality control of in vitro susceptibility testing. Susceptibilities to other antimicrobial agents were reported according to data from the BD-Phoenix system.

β-Lactamase assays.

ESBL production was initially screened for by the ESBL screen flow application of BD-Phoenix. ESBL production was confirmed by a double-disk test to screen for synergy between serine β-lactamase inhibitors (clavulanate and tazobactam) and oxyimino cephalosporins or ATM (13). Commercial disks of amoxicillin-clavulanate and piperacillin-tazobactam (BD Diagnostic Systems) were used as sources of inhibitors. Inhibitor-containing disks were placed 22.5 mm apart (center to center) from those containing the oxyimino cephalosporins and ATM. Analytical isoelectric focusing (IEF) of crude extracts, detection of β-lactamase bands by nitrocefin, and detection of the activity of the β-lactamase bands separated by IEF against β-lactam substrates by a substrate overlaying procedure were assayed as reported previously (18), with an antibiotic concentration of 1 μg/ml in the medium overlay and with E. coli ATCC 25922 as an indicator strain. Substrate hydrolysis was revealed by the occurrence of bacterial growth above the enzyme bands. Reference strains producing TEM-1, TEM-2, TEM-7, TEM-8, TEM-9, TEM-12, SHV-1, SHV-2, SHV-5, and MIR-1 were used as controls, as described previously (18).

Molecular analysis techniques.

PCR amplification of blaCTX-M alleles was carried out with primers CTX-MU1 (5′-ATGTGCAGYACCAGTAARGT) and CTX-MU2 (5′-TGGGTRAARTARGTSACCAGA), designed on conserved regions of blaCTX-M genes, including blaCTX-M-1 to blaCTX-M-30, blaTOHO-1 to blaTOHO-3, blaFEC-1, blaUOE-1, and blaUOE-2 (http://www.lahey.org/studies/webt.stm; EMBL/GenBank accession numbers AB059404, AB098539, AF311345, AY156923, and AY238472). These primers target amplification of a 593-bp internal region of the blaCTX-M genes. The following reaction parameters were used: initial denaturation at 94°C for 7 min; denaturation at 94°C for 50 s, annealing at 50°C for 40 s, and elongation at 72°C for 60 s, repeated for 35 cycles; final extension at 72°C for 5 min. PCR amplification of the allele belonging in the blaCTX-M-3/15/22 group was carried out with primers CTX-M3G-F (5′-GTTACAATGTGTGAGAAGCAG) and CTX-M3G-R (5′-CCGTTTCCGCTATTACAAAC) and the following reaction parameters: initial denaturation at 94°C for 7 min; denaturation at 94°C for 50 s, annealing at 50°C for 40 s, and elongation at 68°C for 60 s, repeated for 35 cycles; final extension at 68°C for 5 min. PCR was always carried out in a 50-μl volume with 30 pmol of each primer, 200 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 0.5 U of the Expand PCR system (Roche Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany) in the reaction buffer provided by the enzyme manufacturer. Direct sequencing of PCR products was carried out as described previously (22) with custom sequencing primers. Both strands were sequenced. Plasmid DNA was extracted by the alkaline lysis method (25). Colony blot hybridization was carried out as described previously (25); final washing was performed with 1× SSC (0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) (or 2× SSC for low-stringency conditions) at 65°C. Southern hybridization was carried out directly on dried gels as described previously (27) with DNA probes labeled with 32P by the random-priming technique. The blaCTX-M probe was made by a 1:1 mixture of amplicons generated with the CTX-MU1 and CTX-MU2 primers from blaCTX-M-1 and blaCTX-M-2, respectively.

Conjugation assays.

Conjugal transfer of resistance determinants was assayed in liquid medium (21) with the E. coli K-12 strain J62 (pro his trp lac Smr) as the recipient. Donor strains in the logarithmic phase of growth were mixed with recipients in early stationary phase in a 1:10 ratio in MH broth, and the mixture was incubated at 37°C for 14 h. Transconjugants were selected on MH agar containing CTX (2 μg/ml) plus streptomycin (1,000 μg/ml). The detection sensitivity of the assay was approximately 10−8 transconjugants per recipient.

PFGE.

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) profiles of genomic DNA were analyzed by means of the Gene Path procedure (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, Calif.) using the no. 5 pathogen group reagent kit and the restriction enzyme SfiI for P. vulgaris and the no. 2 pathogen group reagent kit and the restriction enzyme NotI for E. coli. DNA fragments were electrophoresed in 1% agarose gels in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer with the Gene Path system (Bio-Rad) at 14°C and 6 V/cm for 20 h, with pulse times ranging from 5 to 50 s. Bacteriophage λ concatemers (Bio-Rad) were used as DNA size markers. Clonal relationships based on PFGE patterns were interpreted according to the criteria proposed by Tenover et al. (26).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Detection of CTX-M-producing isolates.

During the period January 2001 to July 2002, at the Laboratory of Clinical Microbiology of the IRCCS San Matteo Hospital of Pavia, a total of 2,682 samples positive for enteric bacteria were processed and 232 ESBL producers were identified by the ESBL screen flow application of the BD-Phoenix system. Twelve of the putative ESBL producers, for which the CTX MICs were higher than those of CAZ in a conventional microdilution susceptibility test, were investigated in this study. The isolates included eight of E. coli, two of P. vulgaris, one of Proteus mirabilis, and one of K. pneumoniae (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Antimicrobial susceptibility, β-lactamase production, and blaCTX-M genes in the isolates of Enterobacteriaceae analyzed in this studylegend

| Species | Isolate | MIC (μg/ml) of:

|

Result of DD synergy testa with:

|

pI(s) by IEF (substrate[s] hydrolyzed)b | blaCTX-M gene | Other drugs to which resistance was shownc | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTX | CAZ | FEP | ATM | CLA | TAZ | |||||

| K. pneumoniae | KPISM01 | >128 | 2 | >128 | >128 | + | + | 8.9 (CTX, FEP, ATM), 7.6, 5.4 | blaCTX-M-15 | AM, AC, PI, PT, GM |

| E. coli | EC10SM01 | 64 | 16 | 16 | 32 | + | + | 8.6 (CTX, FEP, ATM), 5.4 | blaCTX-M-1 | AM, AC, PI, PT, CI, LE, GM |

| EC14SM02 | 128 | 8 | 64 | 32 | + | + | 8.6 (CTX, FEP, ATM), 6.5 | blaCTX-M-1 | AM, AC, PI, PT, CI, LE | |

| EC21SM02 | >128 | 2 | 8 | 64 | + | + | 8.6 (CTX, FEP, ATM), 5.4 | blaCTX-M-1 | AM, AC, PI, PT, CI, LE | |

| EC11SM02 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 16 | + | + | 8.4 (CTX, FEP, ATM), 6.5, 5.4 | —d | AM, AC, PI, PT, CI, LE, GM | |

| EC17SM02 | 64 | 32 | 4 | 16 | + | + | 8.0 (CTX, FEP, ATM), 5.4 | — | AM, AC, PI, PT, CI, LE, GM | |

| EC26SM02 | 32 | 16 | 1 | 16 | − | + (FEP only) | >9.0 (CTX, CAZ, FEP), 5.4 | — | AM, AC, PI, PT, CI, LE, GM | |

| EC27SM02 | >126 | 16 | 2 | 64 | + | + | 8.0 (CTX, FEP, ATM), 5.4 | — | AM, AC, PI, PT, CI, LE, GM | |

| EC28SM01 | >128 | 16 | 2 | 64 | + | + | 8.0 (CTX, FEP, ATM), 5.4 | — | AM, AC, PI, PT, CI, LE, GM | |

| P. vulgaris | PV1SM01 | 32 | 16 | 2 | 32 | + | + | 8.0 (CTX, FEP, ATM), 7.6, 5.4 | blaCTX-M-2 | AM, AC, PI, PT, CI, LE, GM |

| PV19SM02 | >128 | 16 | 8 | >128 | − | + | 8.0 (CTX, FEP, ATM), 7.6 (CTX); 5.4 | blaCTX-M-2 | AM, AC, PI, PT, CI, LE, GM | |

| P. mirabilis | PM15SM02 | 32 | 4 | 8 | 32 | + | + | 8.4 (CTX, FEP, ATM) | — | AM, AC, PI, PT, CI, LE, GM |

| 5.9 (CTX, CAZ, FEP, ATM), 5.4 | ||||||||||

CLA, clavulanate; TAZ, tazobactam; +, detectable synergy between the β-lactamase inhibitor and CTX, CAZ, FEP, and ATM in the double-disk (DD) test; −, absence of detectable synergy between the β-lactamase inhibitor and the extended-spectrum β-lactams.

The pIs of the β-lactamase bands are indicated; the extended-spectrum β-lactams hydrolyzed by each band are in parentheses.

AM, ampicillin; AC, amoxicillin-clavulanate; PI, piperacillin; PT, piperacillin-tazobactam; CI, ciprofloxacin; LE, levofloxacin; GM, gentamicin.

—, no blaCTX-M gene detected.

MICs of extended-spectrum cephalosporins and ATM exhibited a notable variability among different isolates, but they were always ≥2 μg/ml, except for the 1-μg/ml MIC of FEP observed with the E. coli isolate EC26SM02 (Table 1). All isolates were resistant to ampicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, piperacillin, and piperacillin-tazobactam, and most isolates were also resistant to ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, and gentamicin (Table 1). All isolates were susceptible to carbapenems (imipenem and meropenem) and to amikacin, except P. vulgaris PV19SM02, which was intermediate to the latter drug.

A double-disk synergy test yielded a positive result in all cases, although with variable detection sensitivity with different substrate-inhibitor combinations. In particular, clavulanate synergy with either oxyimino cephalosporins or ATM was not detectable for one P. vulgaris isolate (PV19SM02) and one E. coli isolate (EC26SM02); with the same E. coli isolate tazobactam synergy was detectable only with FEP (Table 1).

The resistance phenotypes of the 12 isolates were suggestive of production of a CTX-M-type ESBL. Screening for blaCTX-M determinants by PCR with the CTX-MU1 and CTX-MU2 primers, designed on conserved regions of blaCTX-M genes, yielded an amplification product of the expected size (0.6 kb) from six isolates, including three of E. coli, two of P. vulgaris, and one of K. pneumoniae (Table 1). Sequencing the amplification products from the three E. coli isolates identified the resistance gene as blaCTX-M-1 (Table 1). The genes in the two P. vulgaris isolates were identified as blaCTX-M-2 (Table 1). The gene in the K. pneumoniae isolate was identified as blaUOE-1, blaCTX-M-15, or blaCTX-M-28. In this case, amplification of the entire coding sequence with primers CTX-M3G-F and CTX-M3G-R, followed by direct sequencing, identified the resistance gene as blaCTX-M-15 (Table 1). Colony blot hybridization analysis of the 12 isolates using a blaCTX-M-1/2 probe mixture yielded results that were fully consistent with those of PCR screening (data not shown). The PCR-negative isolates were not recognized by the probe mixture, even under low-stringency hybridization conditions, suggesting that ESBLs other than those of the CTX-M type were produced by these isolates.

Analytical IEF of crude extracts of the 12 isolates revealed heterogeneous patterns, with multiple β-lactamase bands in all cases (Table 1). Some of these bands exhibited activity against oxyimino cephalosporins and ATM in a bioassay. The nature of CTX-M-type enzymes detected by molecular analysis was consistent with the presence of a pI 8.9 ESBL active on CTX, FEP, and ATM in the K. pneumoniae isolate, of a pI 8.6 ESBL active on the same substrates in the three CTX-M-positive E. coli isolates, and of a pI 8.0 ESBL active on the same substrates in the two P. vulgaris isolates. Although CTX-M-15 has been reported to be active also on CAZ (19), activity against this substrate was not detectable in the bioassay, probably because of the relatively low catalytic efficiency exhibited by CTX-M-15 against this substrate (19). The natures of the ESBLs in the CTX-M-negative isolates and of the other enzymes were not investigated in this work and will be the subject of another investigation.

Clonal relationships and distribution of the CTX-M-producing isolates.

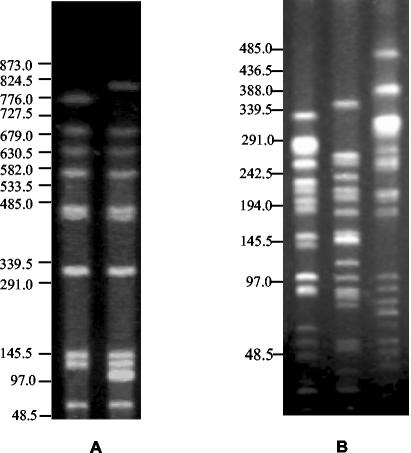

The PFGE profiles of genomic DNA of the P. vulgaris isolates producing CTX-M-2, digested with SfiI, differed from each other by only two bands (Fig. 1A), revealing probable clonal relatedness. On the other hand, the PFGE profiles of genomic DNA of the three E. coli isolates producing CTX-M-1, digested with NotI, were notably different (by more than four bands), indicating that these isolates were clonally unrelated (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

(A) PFGE profiles of genomic DNAs of the CTX-M-2-producing P. vulgaris isolates digested with SfiI. Left lane, isolate PV1SM01; right lane, PV19 isolate PV19SM02. (B) PFGE profiles of genomic DNAs of the CTX-M-1-producing E. coli isolates digested with NotI. Left lane, isolate EC14SM02; middle lane, isolate EC21SM02; right lane, isolate EC10SM01. DNA size standards (in kilobases) are indicated on the left.

The six CTX-M-producing isolates exhibited a different clinical distribution. The K. pneumoniae isolate producing CTX-M-15 was an apparently sporadic isolate from the Hematology ward. The two P. vulgaris isolates producing CTX-M-2 were isolated from the same long-term care ward, although several months apart. The three E. coli isolates producing CTX-M-1 were each from a different ward (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Distribution, clinical features, and clonal relationships of CTX-M-producing clinical isolates of Enterobacteriaceae

| Species | Isolate (enzyme) | Date | Ward | Specimen | PFGE profile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K. pneumoniae | KP1SM01 (CTX-M-15) | January 2001 | Hematology | Blood | NDa |

| E. coli | EC10SM01 (CTX-M-1) | November 2001 | Internal Medicine I | Urine | Unique |

| EC14SM02 (CTX-M-1) | February 2002 | Vascular Surgery | Gangrenous tissue | Unique | |

| EC21SM02 (CTX-M-1) | March 2002 | Internal Medicine II | Urine | Unique | |

| P. vulgaris | PV01SM01 (CTX-M-2) | January 2001 | Long-Term Care I | Urine | A1 |

| PV19SM02 (CTX-M-2) | May 2002 | Long-Term Care I | Decubitus ulcer | A2 |

ND, not determined.

Transferability of the blaCTX-M genes.

Transferability of the CTX-M determinants was assayed in mating experiments using an E. coli recipient and CTX for selection of transconjugants. Results of these experiments showed that the CTX-M-1 determinant was transferable from each E. coli donor at a frequency of approximately 10−4 transconjugants/recipient, while the CTX-M-2 determinant was transferable from each P. vulgaris donor at a frequency of approximately 10−5 transconjugants/recipient. Conjugal transfer of the CTX-M-15 determinant carried by the K. pneumoniae isolate was not detectable. All E. coli transconjugants were recognized by the blaCTX-M-1/2 probe mixture in a colony blot hybridization (data not shown), confirming that transfer of the CTX-M determinant had occurred.

Transconjugants derived from the CTX-M-1-positive E. coli strains produced a single pI 8.6 β-lactamase with ESBL activity and showed similar patterns of decreased susceptibility to oxyimino cephalosporins and ATM (Table 3). All these transconjugants apparently harbored the same plasmid, named pSMEC10, whose size was estimated to be approximately 50 kb according to results of restriction analysis (Fig. 2A) and which was recognized by the blaCTX-M-1/2 probe mixture in a Southern hybridization experiment (data not shown). Transconjugants derived from the CTX-M-2-positive P. vulgaris isolates produced two β-lactamases, including a pI 8 ESBL and a pI 5.4 non-ESBL (that was likely TEM-1), and showed similar patterns of decreased susceptibility to oxyimino cephalosporins and ATM (Table 3). All these transconjugants apparently harbored the same plasmid, named pSMPV1, whose size was estimated to be approximately 55 kb according to results of restriction analysis (Fig. 2B) and which was recognized by the blaCTX-M-1/2 probe mixture in a Southern hybridization experiment (data not shown). After digestion with the same enzyme (PstI), plasmids pSMEC10 and pSMPV1 exhibited different restriction profiles (Fig. 2).

TABLE 3.

Antimicrobial susceptibilities and β-lactamase production of CTX-M-positive E. coli transconjugants obtained in mating experimentsc

| Transconjuganta or strain (en By me) | MIC (μg/ml) of:

|

pI(s) by IEF (substrate hydrolyzed) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTX | CAZ | FEP | ATM | ||

| J62 × EC10SM01 (CTX-M-1) | 16 | 8 | 16 | 16 | 8.6 (CTX, FEP, ATM) |

| J62 × EC14SM02 (CTX-M-1) | 32 | 4 | 16 | 16 | 8.6 (CTX, FEP, ATM) |

| J62 × EC21SM02 (CTX-M-1) | 32 | 4 | 32 | 16 | 8.6 (CTX, FEP, ATM) |

| J62 × PV01SM01 (CTX-M-2) | 32 | 2 | 16 | 2 | 8.0 (CTX, FEP, ATM), 5.4 |

| J62 × PV19SM02 (CTX-M-2) | 16 | 1 | 16 | 4 | 8.0 (CTX, FEP, ATM), 5.4 |

| J62 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.25 | NDb |

From each conjugation experiment, one transconjugant was randomly selected and subjected to in vitro susceptibility testing and IEF analysis.

ND, no band of enzyme activity was detectable.

Susceptibility of the J62 recipient strain is shown for comparison.

FIG. 2.

(A) EcoRV and PstI restriction profiles (lanes V and P, respectively) of the plasmid extracted from a transconjugant obtained with E. coli EC10SM01 as the donor. Plasmids from transconjugants obtained from E. coli EC14SM02 and EC21SM02 exhibited apparently identical restriction profiles and are not shown. (B) HindIII and PstI restriction profile (lanes H and P, respectively) of the plasmid extracted from a transconjugant obtained using P. vulgaris PV1SM01 as the donor. A plasmid from a transconjugant obtained from P. vulgaris PV19SM02 exhibited an apparently identical restriction profile and is not shown. DNA size standards (in kilobases) are indicated on the left.

Concluding remarks.

To our best knowledge this is the first report of the isolation of multiple CTX-M-type enzymes from an Italian hospital. Three enzyme classes, namely, CTX-M-1, CTX-M-2, and CTX-M-15, were detected in the same hospital. The three enzymes exhibited different distributions: CTX-M-1 was detected in E. coli, CTX-M-2 was detected in P. vulgaris (a species that was not previously reported among CTX-M producers), and CTX-M-15 was detected in K. pneumoniae. CTX-M-15 belongs in the CTX-M-1 lineage and has previously been detected in India, Japan, Bulgaria, and Poland (19). Compared to CTX-M-3, from which it differs by a single amino acid residue, it exhibits an increased activity on CAZ (19).

The different distributions of the three CTX-M determinants likely reflect differences in their genetic vehicles. Conjugational transfer could not be detected for the CTX-M-15 determinant carried by the K. pneumoniae isolate, while both the CTX-M-1 determinant found in E. coli and the CTX-M-2 determinant found in P. vulgaris were readily transferable by conjugation, although at different frequencies. Finding the same CTX-M-1-encoding plasmid in three clonally unrelated strains of E. coli from three different wards indicates a notable spreading potential for this plasmid and suggests that horizontal transfer could be the principal mechanism of spreading blaCTX-M-1 in the hospital environment. On the other hand, the two P. vulgaris isolates producing CTX-M-2 appeared to be related to each other and were from the same ward, suggesting a clonal spread within that ward. The strains producing different enzymes were detected in different wards.

Isolates of Enterobacteriaceae producing ESBLs other than those of the CTX-M type had already been detected in the same hospital (16-18). The number of CTX-M-producing isolates was low, overall, considering the total number of enteric bacterial isolates and also the total number of ESBL producers isolated during the same period. However, note that the screening criterion adopted was based on simple phenotypic features and that the number of CTX-M-producing isolates detected in this work could be underestimated. In fact, strains containing blaCTX-M genes but also producing additional enzymes resulting in CAZ MICs higher than those of CTX would have been missed. Systematic screening by molecular methods will be necessary to determine the prevalence of CTX-M-producing strains within our hospital. PCR screening using the CTX-MU primers, designed on highly conserved sequences of blaCTX-M genes, is expected to be most useful for this purpose.

Concerning phenotypic detection, the ESBL screen flow application of the BD-Phoenix system appeared to be capable of detection of strains producing ESBLs of the CTX-M type. When a double-disk diffusion test was used, tazobactam appeared to be slightly more sensitive than clavulanate for detection of similar ESBL producers.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to Elisabetta Nucleo and Melissa Spalla for their excellent technical collaboration.

This work was supported in part by grant no. 2001068755_003 from MIUR (PRIN 2001).

REFERENCES

- 1.Arduino, S. M., P. H. Roy, G. A. Jacoby, B. E. Orman, S. A. Pineiro, and D. Centron. 2002. blaCTX-M-2 is located in an unusual class 1 integron (In35) which includes Orf513. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:2303-2306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baraniak, A., J. Fiett, A. Sulikowska, W. Hryniewicz, and M. Gniadkowski. 2002. Countrywide spread of CTX-M-3 extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing microorganisms of the family Enterobacteriaceae in Poland. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:151-159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barthélémy, M., J. Péduzzi, H. Bernard, C. Tancrède, and R. Labia. 1992. Close amino acid sequence relationship between the plasmid-mediated extended-spectrum β-lactamase MEN-1 and chromosomally-encoded enzymes of Klebsiella oxytoca. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1122:15-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauernfeind, A., H. Grimm, and S. Schweigart. 1990. A new plasmidic cefotaximase in a clinical isolate of Escherichia coli. Infection 18:294-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonnet, R., J. L. M. Sampaio, R. Labia, C. De Champs, D. Sirot, C. Chanal, and J. Sirot. 2000. A novel CTX-M β-lactamase (CTX-M-8) in cefotaxime-resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolated in Brazil. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:1936-1942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bou, G., M. Cartelle, M. Tomas, D. Canle, F. Molina, R. Moure, J. M. Eiros, and A. Guerrero. 2002. Identification and broad dissemination of the CTX-M-14 β-lactamase in different Escherichia coli strains in the northwest area of Spain. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:4030-4036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradford, P. 2001. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases in the 21st century: characterization, epidemiology, and detection of this important resistance threat. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14:933-951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chanawong, A., F. H. M'Zali, J. Heritage, J.-H. Xiong, and P. M. Hawkey. 2002. Three cefotaximases, CTX-M-9, CTX-M-13, and CTX-M-14, among Enterobacteriaceae in the People's Republic of China. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:630-637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Decousser, J. W., L. Poirel, and P. Nordmann. 2001. Characterization of a chromosomally encoded extended-spectrum class A β-lactamase from Kluyvera cryocrescens. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:3595-3598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Di Conza, J., J. A. Ayala, P. Power, M. Mollerach, and G. Gutkind. 2002. Novel class 1 integron (InS21) carrying blaCTX-M-2 in Salmonella enterica serovar Infantis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:2257-2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dutour, C., R. Bonnet, H. Marchandin, M. Boyer, C. Chanal, D. Sirot, and J. Sirot. 2002. CTX-M-1, CTX-M-3, and CTX-M-14 β-lactamases from Enterobacteriaceae isolated in France. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:534-537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Humeniuk, C., G. Arlet, V. Gautier, P. Grimont, R. Labia, and A. Philippon. 2002. β-Lactamases of Kluyvera ascorbata, probable progenitors of some plasmid-encoded CTX-M types. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:3045-3049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jarlier, V., M. H. Nicolas, G. Fournier, and A. Philippon. 1988. Extended broad-spectrum β-lactamases conferring transferable resistance to newer beta-lactam agents in Enterobacteriaceae: hospital prevalence and susceptibility patterns. Rev. Infect. Dis. 10:867-878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karim, A., L. Poirel, S. Nagarajan, and P. Nordmann. 2001. Plasmid-mediated extended-spectrum β-lactamase (CTX-M-3 like) from India and gene association with insertion sequence ISEcp1. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 201:237-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2000. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. Approved standard M7-A5. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 16.Pagani, L., F. Luzzaro, P. Ronza, A. Rossi, P. Micheletti, F. Porta, and E. Romero. 1994. Outbreak of extended-spectrum β-lactamase producing Serratia marcescens in an intensive care unit. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 10:39-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pagani, L., M. Perilli, R. Migliavacca, F. Luzzaro, and G. Amicosante. 1998. Extended-spectrum TEM- and SHV-type β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae strains causing outbreaks in intensive care units in Italy. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 19:765-772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pagani, L., R. Migliavacca, L. Pallecchi, C. Matti, E. Giacobone, G. Amicosante, E. Romero, and G. M. Rossolini. 2002. Emerging extended-spectrum β-lactamases in Proteus mirabilis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:1549-1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poirel, L., M. Gniadkowski, and P. Nordmann. 2002. Biochemical analysis of the ceftazidime-hydrolysing extended-spectrum β-lactamase CTX-M-15 and of its structurally-related β-lactamase CTX-M-3. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 50:1031-1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poirel, L., P. Kämpfer, and P. Nordmann. 2002. Chromosome-encoded Ambler class A β-lactamase of Kluyvera georgiana, a probable progenitor of a subgroup of CTX-M extended-spectrum β-lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:4038-4040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Provence, D. L., and R. Curtiss III. 1994. Gene transfer in gram-negative bacteria, p. 319-347, In P. Gerhardt, R. G. E. Murray, W. A. Wood, and N. R. Krieg (ed.), Methods for general and molecular bacteriology. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 22.Riccio, M. L., N. Franceschini, L. Boschi, B. Caravelli, G. Cornaglia, R. Fontana, G. Amicosante, and G. M. Rossolini. 2000. Characterization of the metallo-β-lactamase determinant of Acinetobacter baumannii AC-54/97 reveals the existence of blaIMP allelic variants carried by gene cassettes of different phylogeny. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:1229-1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sabaté, M., F. Navarro, E. Miró, S. Campoy, B. Mirelis, J. Barbé, and G. Prats. 2002. Novel complex sul1-type integron in Escherichia coli carrying blaCTX-M-9. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:2656-2661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saladin, M., V. T. B. Cao, T. Lambert, J.-L. Donay, J.-L. Herrmann, Z. Ould-Hocine, C. Verdet, F. Delisle, A. Philippon, and G. Arlet. 2002. Diversity of CTX-M β-lactamases and their promoter regions from Enterobacteriaceae isolated in three Parisian hospitals. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 209:161-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russel. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 26.Tenover, F. C., R. D. Arbeit, R. V. Goering, P. A. Mickelsen, B. E. Murray, D. H. Persing, and B. Swaminathan. 1995. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2233-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsao, S. G., C. F. Brunk, and R. E. Pearlman. 1983. Hybridization of nucleic acids directly in agarose gels. Anal. Biochem. 131:365-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsouvelekis, L. S., E. Tzelepi, P. T. Tassios, and N. J. Legakis. 2000. CTX-M-type β-lactamases: an emerging group of extended-spectrum enzymes. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 14:137-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang, H., S. Kelkar, W. Wu, M. Chen, and J. P. Quinn. 2003. Clinical isolates of Enterobacteriaceae producing extended-spectrum β-lactamases: prevalence of CTX-M-3 at a hospital in China. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:790-793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu, W. L., P. L. Winokur, D. L. Von Stein, M. A. Pfaller, J. H. Wang, and R. N. Jones. 2002. First description of Klebsiella pneumoniae harboring CTX-M β-lactamases (CTX-M-14 and CTX-M-3) in Taiwan. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1098-1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]