Abstract

Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other gram-negative isolates from patients with cystic fibrosis (CF) may be difficult to identify because of their marked phenotypic diversity. We examined 200 gram-negative clinical isolates from CF respiratory tract specimens and compared identification by biochemical testing and real-time PCR with multiple different target sequences using a standardized combination of biochemical testing and molecular identification, including 16S rRNA partial sequencing and gyrB PCR and sequencing as a “gold standard.” Of 50 isolates easily identified phenotypically as P. aeruginosa, all were positive with PCR primers for gyrB or oprI, 98% were positive with exotoxin A primers, and 90% were positive with algD primers. Of 50 P. aeruginosa isolates that could be identified by basic biochemical testing, 100% were positive by real-time PCR with gyrB or oprI primers, 96% were positive with exotoxin A primers, and 92% were positive with algD primers. For isolates requiring more-extensive biochemical evaluation, 13 isolates were identified as P. aeruginosa; all 13 were positive with gyrB primers, 12 of 13 were positive with oprI primers, 11 of 13 were positive with exotoxin A primers, and 10 of 13 were positive with algD primers. A single false-positive P. aeruginosa result was seen with oprI primers. The best-performing commercial biochemical testing was in exact agreement with molecular identification only 60% of the time for this most difficult group. Real-time PCR had costs similar to those of commercial biochemical testing but a much shorter turnaround time. Given the diversity of these CF isolates, real-time PCR with a combination of two target sequences appears to be the optimum choice for identification of atypical P. aeruginosa and for non-P. aeruginosa gram-negative isolates.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is the most significant pathogen affecting patients with cystic fibrosis (CF). It is often acquired in the first few years of life and causes chronic airway infections, which ultimately result in death. While P. aeruginosa is not thought of as an organism that is difficult to identify in the microbiology laboratory, CF isolates often have unique phenotypes, including the loss of pigment production, synthesis of rough lipopolysaccharide devoid of O side chains, and development of mucoidy (18). While the presence of mucoidy may be helpful in identifying CF isolates of P. aeruginosa, some of the other characteristics may make these isolates more difficult to identify. Both commercial methods of identification and standard biochemical testing may be lengthy and inaccurate (10, 11). In addition, CF patients often have other nonfermenting gram-negative bacilli isolated from their respiratory secretions, making rapid isolation and identification of P. aeruginosa even more difficult (1, 7). While sequencing 16S rRNA genes in CF isolates of P. aeruginosa and other gram-negative bacilli has utility (6), it may be expensive and time-consuming.

The Cystic Fibrosis Foundation-funded Therapeutic Development Network (TDN) Resource Center for Microbiology processes thousands of respiratory tract samples from CF patients enrolled in clinical trials, and the prompt isolation and identification of P. aeruginosa and other gram-negative pathogens are often needed for patients to meet entrance criteria for the studies. We recently compared the use of real-time PCR with standard biochemical testing for the identification of gram-negative isolates from CF respiratory tract samples sent to the laboratory for microbiological evaluation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Specimen processing.

Sputum samples, oropharyngeal swabs, and bronchoalveolar lavage specimens were obtained during the course of routine clinical care at Children's Hospital and Regional Medical Center (CHRMC) in Seattle, Wash., or were sent to the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation TDN Resource Center for Microbiology at CHRMC as part of an approved clinical research protocol. The protocol for the present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at CHRMC.

Specimens were processed and plated on selective media as previously described (1). Culture media were purchased from BBL Microbiology Systems (Cockeysville, Md.), except where otherwise noted. Isolated colonies representing distinct morphotypes of gram-negative bacilli were subcultured from MacConkey, DNase, or oxidative-fermentative medium with polymyxin, bacitracin, and lactose (OFPBL) agar onto blood agar-MacConkey agar biplates and incubated at 37°C until growth and purity could be confirmed.

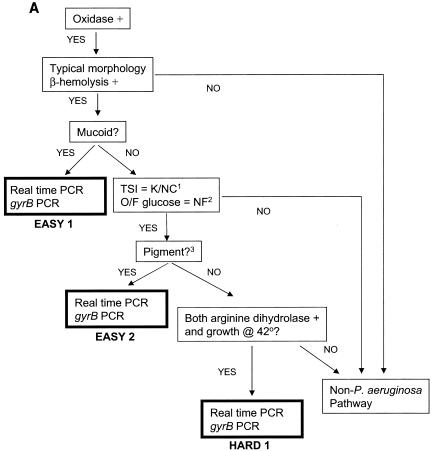

Criteria for specific categories of isolates were established a priori and are shown in Fig. 1. Isolates were assigned to one of five groups (easy 1 [E1], E2, hard 1 [H1], H2, and H3) based on ease of identification. All isolates were evaluated phenotypically for mucoidy and colonial morphology, as well as for beta hemolysis on sheep blood agar. In addition, all isolates had a cytochrome oxidase spot test (10) (Sigma Biochemicals, St. Louis, Mo.). E1 isolates were mucoid, beta-hemolytic, and oxidase positive. Isolates that did not meet E1 criteria were further evaluated with a short set of biochemical tests (triple-sugar iron [TSI] and oxidative-fermentative agar with glucose [OF glucose] in addition to the above). E2 isolates had typical morphology (including either a characteristic odor or metallic sheen or both), were beta-hemolytic and oxidase positive, produced blue-green or reddish brown pigment, had a TSI reaction of alkaline over no change, and were OF glucose nonfermenters (10).

FIG. 1.

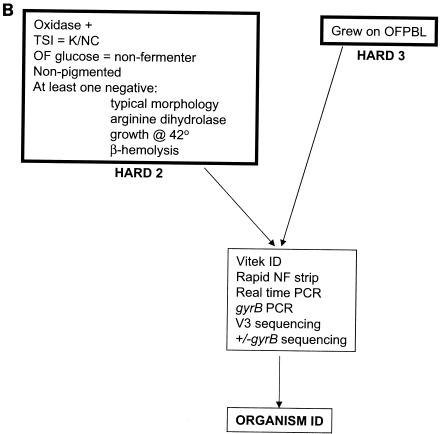

Flow of organisms through biochemical testing and PCR identification. (A) P. aeruginosa pathway: E1, E2, and H1 isolates. K/NC, alkaline over no change; NF, nonfermenter; pigment?, blue-green or reddish brown pigment. (B) Non-P. aeruginosa pathway for isolates unlikely to be P. aeruginosa.

If the identification of P. aeruginosa was in doubt after these determinations, additional assays were performed. In addition to the short set above, this long set also included assays for Moeller's arginine dihydrolase (PML Microbiologicals, Wilsonville, Oreg.) and assays of growth at 42°C. Isolates were identified as P. aeruginosa and designated H1 if they were nonpigmented, beta-hemolytic, OF glucose nonfermenters, and oxidase and arginine dihydrolase positive; had a TSI reaction of alkaline over no change; grew at 42°C; and exhibited typical morphology.

Isolates were designated H2 if they were oxidase positive, were nonfermenters on OF glucose, were nonpigmented, and were either not beta-hemolytic or had at least one negative reaction in the long set of biochemical assays. Such isolates were subsequently tested with RapID NF Plus and a Vitek GNI+ card (both from bioMerieux, Hazelwood, Mo.).

Additional isolates, not expected to be P. aeruginosa, that grew on OFPBL agar and that were isolated from either OFPBL or from MacConkey agar were designated H3. Biochemical identification of these isolates was attempted by using RapID NF plus and a Vitek GNI+ card plus the long set of biochemical assays described above, with the potential for addition of other tests including tests for OF maltose, OF sucrose, OF mannitol, OF xylose, urease agar, and Moeller's lysine decarboxylase (the last two from PML). There were 25 isolates in each of the E1 and E2 categories and 50 isolates in each of the H1, H2, and H3 categories.

Real-time PCR.

All isolates were subjected to real-time PCR using four target sequences. Organisms were coded prior to testing and tested in a blind fashion. Three published gene sequences that have been reported for use in the identification of P. aeruginosa were targeted for PCR amplification: oprI (OPR) (3, 4, 5), algD (VIC) (2, 19), and the exotoxin A gene (ETA) (9, 17). The designated primer pairs are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Primer sequences

| Primer | Oligonucleotide sequence (5′-3′) (no. of nucleotides)a | Target sequence, amplicon size (bp) | Purpose | Reference(s) or source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRV3-1 | CGG YCC AGA CTC CTA CGG G (19) | 16S rDNA 330-533, ∼200 | Bacterial identification by PCR and sequencing | 12 |

| SRV3-2 | TTA CCG CGG CTG CTG GCA C (19) | |||

| gyrPA-398 | CCT GAC CAT CCG TCG CCA CAA C (22) | P. aeruginosa gyrB 398-620, 222 | P. aeruginosa-specific PCR | This study |

| gyrPA-620 | CGC AGC AGG ATG CCG ACG CC (20) | |||

| ETA-1 | GAC AAC GCC CTC AGC ATC ACC AGC (24) | P. aeruginosa ETA, 367 | P. aeruginosa-specific PCR | 9, 17 |

| ETA-2 | CGC TGG CCC ATT CGC TCC AGC GCT (24) | |||

| VIC-1 | TTC CCT CGC AGA GAA AAC ATC (26) | P. aeruginosa algD encoding GDP mannose dehydrogenase 520 | P. aeruginosa-specific PCR | 2, 19 |

| VIC-2 | CCT GGT TGA TCA GGT CGA TCT (21) | |||

| OPR-1 | GCT CTG GCT CTG GCT GCT (18) | P. aeruginosa oprl, encoding surface lipoprotein 1, 330 | P. aeruginosa-specific PCR | 3, 4 |

| OPR-2 | AGG GCA CGC TCG TTA GCC (18) |

Y = C or T.

In addition, a fourth sequence was amplified with primers developed specifically for this study. P. aeruginosa gyrB-specific primers gyrPA-398 and gyrPA-620 (Table 1) were chosen based on multisequence alignment of 88 gyrB sequence entries within the genus Pseudomonas contained in the ICB database (http://seasquirt.mbio.co.jp/icb/index.php) at the time. The gyrB primers were checked further against both the ICB database and GenBank to confirm their P. aeruginosa specificity. The ICB database is housed at the Marine Biotechnology Institute in Kamaishi, Japan, and acts as a central collection point for prokaryotic protein-coding gene data. The database is designed to provide the scientific community with a reference point for using gyrB as an evolutionary and identification marker. This growing bacterial gyrB database has been used for identification and classification of bacteria. At present the database publishes a comprehensive collection of gyrB sequence data, alignments, and resources, which includes 214 (as of 28 April 2003) sequence entries under the genus Pseudomonas.

Isolated colonies were picked and resuspended in 1 ml of molecular-grade H2O and diluted to a 0.5 McFarland concentration. A 1:10 dilution of the 0.5 McFarland suspension was boiled for 10 min, chilled on ice, and added to PCR SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) with 0.1 μmol of each of the primers. Uracil-N-glycosylase was incorporated into the PCR SYBR Green Master Mix for amplicon control. All real-time PCRs were performed on the iCYCLER (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.).

Based on the melting temperature properties of the primers, two thermocycling programs were used for testing the four primer pairs. A 5-min 20°C uracil-N-glycosylase treatment step followed by a 2-min 95°C denaturation step was used for both programs before the 40-cycle thermocycling conditions. For VIC and OPR primer pairs a three-temperature cycling condition was used, composed of a 30-s denaturation step at 94°C, a 30-s annealing step at 58°C, and a 30-s polymerization step at 72°C. Thermocycling conditions used for the ETA and gyrB primer pairs differed only in the annealing temperature of 68°C. A 5-min postthermocycling end-filling step at 72°C was followed by melt curve analysis. The melt curve analysis was achieved by tracing the fluorophore signal intensity beginning at the specific annealing temperature of the program and then increasing the temperature in 0.5°C increments to end at 95°C. The mathematical conversion of the first derivative of the melting curve to melting peak was used for determination of the amplicon specificity.

DNA sequence analysis.

16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) variable region 3 (16S-V3) PCR amplification was performed with the ABI GeneAmp PCR System 9700 with the following conditions: 94°C for 2 min; 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 62°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s; followed by 72°C for 10 min as a final extension step. gyrB sequencing was performed with the amplicons generated from cold amplification (without the SYBR Green fluorophore) by using the gyrB primer pair. Both PCR mixtures used GeneAmp PCR core reagents (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's directions and contained 0.1 μmol each of the primers for both 16S-V3 and gyrB PCRs.

DNA sequencing was carried out with the DNA sequencing kit BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction and an ABI PRISM 310 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems). The sequencing thermocycling steps used were 96°C for 30 s and 25 cycles of 96°C for 10 s and 60°C for 10 s. Sequencing chromatographs generated from both forward and reverse strands of the PCR template were edited with Seqman (DNASTAR, Inc.). The resulting partial 16S sequences were used for a sequence similarity search against GenBank, and the gyrB sequences were compared with those published for P. aeruginosa in the ICB database.

Molecular identification.

Molecular identification for this study consisted of gyrB real-time PCR of all isolates (including E1 and E2), with confirmation by 16S-V3 (12) rRNA sequencing to positively identify non-P. aeruginosa gram-negative bacilli and by gyrB sequencing to positively identify P. aeruginosa. For E1, E2, and H1, only gyrB PCR was performed, unless there was a discrepancy in the results of VIC, ETA, and OPR real-time PCR, in which case 16S-V3 sequencing was also performed to verify that the isolate was in the P. aeruginosa group. For all H2 and H3 isolates, 16S-V3 sequencing was performed routinely and sequencing of the gyrB amplicon was performed when 16S-V3 sequencing designated an isolate as being in the P. aeruginosa group (13 isolates, 12 H2 isolates and 1 H3 isolate).

The 16S-V3 region contains sufficient sequence information for speciation of nonpseudomonal gram-negative bacilli including Burkholderia cepacia, Achromobacter xylosoxidans, and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (unpublished data). However, the 16S-V3 segment is insufficient for species identification within the Pseudomonas genus, although it is able to separate the pseudomonal species into two major groups, one of which contains P. aeruginosa. The gyrB sequence is specific for P. aeruginosa (8, 20) and was used to confirm P. aeruginosa.

Positive identification of P. aeruginosa.

The “gold standard” for designation of the E1 and E2 isolates as P. aeruginosa was standard biochemical identification. By their very definition, these isolates could readily be designated P. aeruginosa based on their growth characteristics and biochemical reactions. The gold standard for designation of H1 isolates as P. aeruginosa in this study was a combination of biochemical testing and molecular identification. For H2 and H3 isolates the gold standard for designating an isolate P. aeruginosa in this study was molecular identification based on 16S-V3 and gyrB sequencing.

Statistical methods.

Data analysis included descriptive summarization of test results using counts and proportions. For the 150 hard isolates included in the study, sensitivity and specificity with corresponding 95% binomial exact confidence intervals were calculated for each target sequence, relative to the gold standard of molecular identification as defined above.

RESULTS

Study population.

Two hundred gram-negative bacterial isolates from CF patients were included in the study. One hundred seventy-five were from sputum, 21 were from oropharyngeal swabs, and 4 were from bronchoalveolar lavage specimens. Isolates were categorized based on ease of identification (Fig. 1). Easy isolates could be identified morphologically and with the performance of minimal biochemical testing. Hard isolates required additional testing, and the criteria for the third subcategory (H3) were specifically selected to include non-P. aeruginosa gram-negative bacilli by requiring that they grow on OFPBL agar. By design, the study included fixed numbers within each category of isolates, including 50 easy (25 each of E1 and E2) and 150 hard (50 each of H1, H2, and H3) isolates to reflect the spectrum of CF gram-negative bacterial isolates. During the study, four Pseudomonas fluorescens isolates from CF patients were added as negative controls to evaluate the ability of the specific primer pairs to discriminate Pseudomonas spp. other than Pseudomonas aeruginosa. These four isolates were not recovered on OFPBL.

Real-time PCR results.

Table 2 summarizes the data for the three PCR targets within the five groups of easy and hard isolates, with their corresponding molecular identifications. All three targets were very good for identification of P. aeruginosa. OPR was the best single target sequence, correctly identifying 112 of the 113 P. aeruginosa isolates. However, one non-P. aeruginosa isolate (actually A. xylosoxidans) was also positive with the OPR primers.

TABLE 2.

Agreement between real-time PCR results and molecular identificationa

| Organism group (n)b | 16S-V3 sequencing result (n) | gyrB PCR result (n) | gyrB sequencing result (n) | No. (%) of isolates positive by:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VIC PCR | ETA PCR | OPR PCR | ||||

| E1 (25) | NDc | P. aeruginosa (25) | ND | 23 (92) | 24 (96) | 25 (100) |

| E2 (25) | ND | P. aeruginosa (25) | ND | 22 (88) | 25 (100) | 25 (100) |

| H1 (50) | ND | P. aeruginosa (50) | ND | 46 (92) | 48 (96) | 50 (100) |

| H2 (50) | P. aeruginosa group (12) | P. aeruginosa (12) | P. aeruginosa (12) | 10 (83) | 11 (92) | 12 (100) |

| Other GNR (38) | Not P. aeruginosa (38) | ND | 0 | 0 | 1 (3) | |

| H3 (50) | P. aeruginosa group (1) | P. aeruginosa (1) | P. aeruginosa (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Other GNRd (49) | Not P. aeruginosa (49) | ND | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Controls (4) | Other GNR (4) | Not P. aeruginosa (4) | ND | 0 | 0 | 0 |

For all discrepancies between VIC, ETA, and OPR real-time PCR results, 16S-V3 sequencing was performed to verify that isolates were in the P. aeruginosa group.

n, number of isolates.

ND, not routinely done.

GNR, gram-negative rod.

For the 150 hard isolates, the sensitivity and specificity of each individual primer pair relative to molecular identification as P. aeruginosa or non-P. aeruginosa were calculated (Table 3). The OPR primer had the best combination of sensitivity (98.4%) and specificity (98.9%) for the hard isolates. Calculations were limited to the hard isolates because this is the type of isolates for which real-time PCR would have diagnostic utility.

TABLE 3.

Sensitivity and specificity of PCR primers relative to molecular identification of 150 hard isolates as P. aeruginosa or non-P. aeruginosa

| Sequence amplified by PCR | PCR result for isolates for which molecular identification was:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

P. aeruginosa (n = 63)

|

Non-P. aeruginosa (n = 87)

|

|||||

| No. PCR positive | Sensitivity (%) | 95% CIa (%) | No. PCR negative | Specificity (%) | 95% CI (%) | |

| VIC | 56 | 88.9 | 78.4, 95.4 | 87 | 100 | 96.6, 100b |

| ETA | 59 | 93.7 | 84.5, 98.2 | 87 | 100 | 96.6, 100b |

| OPR | 62 | 98.4 | 91.5, 100 | 86 | 98.9 | 93.8, 100 |

CI, confidence interval.

One-sided 95% CI.

Identification by standard biochemical testing.

Only isolates categorized as H2 and H3 underwent extended biochemical analysis, including the use of commercial systems. The four control isolates also had extended biochemical analysis performed. Biochemical identification by commercial systems (RapID NF Plus and Vitek GNI+) was compared with molecular identification by sequencing (Table 4). Exact agreement between each commercial system and the molecular identification ranged between 52 and 60% (genus and species); the results for RapID NF Plus and Vitek GNI+ were comparable. Relative agreement (correct at genus level) had a wider range (0 to 24%) and was lower for the RapID NF Plus for both H2 and H3 isolates. Lack of agreement was seen in up to 16% of isolates in the H2 and H3 categories, and no biochemical identification was reported for up to 28% of isolates in the H3 category.

TABLE 4.

Agreement between biochemical results and molecular identification for H2 and H3 isolates and controls

| Organism group (n) and test | No. (%) of isolates for which there was:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exact agreement | Relative agreement | No agreement | No biochemical identification | |

| H2 (50) | ||||

| RNFg | 30 (60) | 3 (6)a | 8 (16) | 9 (18) |

| Vitek | 26 (52) | 8 (16)b | 7 (14) | 9 (18) |

| H3 (50) | ||||

| RNF | 28 (56) | 0 | 8 (16) | 14 (28) |

| Vitek | 26 (52) | 12 (24)c | 2 (4) | 10 (20) |

| Controls (4) | ||||

| RNF | 0 | 3d | 0 | 1 |

| Vitek | 0 | 3e | 0 | 1f |

Results (molecular/biochemical) were as follows: Burkholderia sp., not B. cepacia/Burkholderia gladioli; nontermenting gram-negative rod (NFGNR) (GenBank Agrobacterium cluster)/Agrobacterium radiobacter?; NFGNR/Sphingomonas paucimobilis.

Results (molecular/biochemical) were as follows: A. xylosoxidans/NFGNR (two occurrences); P. aeruginosa/NFGNR; S. maltophilia/NFGNR; NFGNR (GenBank unnamed)/Pasteurella haemolytica; NFGNR (GenBank Agrobacterium cluster)/A. radiobactor (two occurrences); Agrobacterium sp./A. radiobacter (delete?); Enterobacter sp. (GenBank Enterobacter cluster)/Enterobacter cloacae.

Results (molecular/biochemical) were as follows: A. xylosoxidans/NFGNR (nine occurrences); NFGNR (GenBank Lautropia cluster)/NFGNR; Chryseobacterium sp./Chryseobacterium indologenes (two occurrences).

Results (molecular/biochemical) were as follows: Pseudomonas sp. (not P. aeruginosa)/P. fluorescens; Pseudomonas sp. (not P. aeruginosa)/P. fluorescens or Pseudomonas putida (two occurrences).

Results (molecular/biochemical) were as follows: Pseudomonas sp. (not P. aeruginosa)/Pseudomonas stutzeri; Pseudomonas sp. (not P. aeruginosa)/P. fluorescens or P. putida (two occurrences).

Vitek GNI+ card testing not done.

RNF, RapID NF plus.

Cost and time analysis.

Monetary costs for both real-time PCR and molecular identification were estimated based on labor costs and prices for reagents, supplies, and equipment maintenance. The cost of performing real-time PCR would average $20 per isolate for consumables and equipment maintenance. Labor costs would be higher if fewer specimens were processed, ranging between $10 and $50 per isolate. Given the expected volume in the CF laboratory, $20 per isolate was assumed, for a total average cost of $40 per organism.

The cost of standard biochemical testing was calculated based on the actual cost of performing 1,400 cultures per year with an estimate of three gram-negative isolates per culture (1). The cost for organism identification by standard biochemical testing would average $39 per isolate.

The amount of time (both the actual amount of technologist time spent processing each isolate and the turnaround time from specimen arrival in the laboratory to reporting of the final identification) was also estimated for real-time PCR, for sequencing, and for biochemical testing based on actual performance of the tests. These estimates assumed a common starting time subsequent to isolate subculture and assurance of culture purity. Real-time PCR takes less than 3 h from start to finish and after the reaction is set up does not require any hands-on time by the technologist. PCR amplification and sequencing require approximately one working day to perform and are much more labor-intensive. Biochemical testing takes the longest time to perform and requires extensive hands-on work by the technologist, both for setup and for ongoing evaluation. Biochemical tests generally require from 18 to 48 h of incubation for results to be read. There generally must be sufficient growth in the test system to ensure purity and to elicit the biochemical reaction. In addition, tests are often performed sequentially, with the results of one panel of assays dictating which tests would subsequently be useful. Thus, for H1, H2, and H3 isolates, 24, 48, and 72 h, respectively, at a minimum are required for identification. Throughout this time period, the technologist is required to monitor growth, read results, and select and perform setup for further testing.

DISCUSSION

The identification of nonfermenting gram-negative bacilli from CF respiratory samples can be challenging. The phenotype of P. aeruginosa may be dramatically altered in the microenvironment of the CF lung (13), and other difficult-to-identify gram-negative bacilli may also be present (1, 6, 7). Biochemical testing is frequently required to positively identify these organisms and requires the use of multiple assays, with a composite result predicting the most likely identification (10). Both standard methods and commercially available biochemical testing kits may be inaccurate (7, 11, 15, 16).

Perhaps the greatest difficulty encountered is the amount of time required to identify organisms. Caregivers treating pulmonary exacerbation use organism identification along with susceptibility testing to select antimicrobial therapy, and a delay in accurate diagnosis may prolong hospitalization or delay effective treatment. In the clinical research setting, the presence of specific organisms may be an inclusion or exclusion criterion, making prompt microbiological characterization crucial to study enrollment.

In this study we were able to accurately identify both mucoid and nonmucoid P. aeruginosa isolates that were oxidase positive and pigmented or of other typical morphology with minimal biochemical testing and without the need for molecular techniques. In fact the identification of P. aeruginosa has traditionally relied on phenotypic methods. This standard still is the most accurate when dealing with typical isolates of P. aeruginosa. In CF patients, however, P. aeruginosa isolates have adapted to the unique environment of the diseased airway and display unusual phenotypic reactions, including lack of hemolysis and pigment production and a negative reaction for arginine dihydrolase. In addition, some of these isolates can be biochemically inert, thus indistinguishable from A. xylosoxidans and other oxidase-positive gram-negative bacilli.

Although molecular methods have been reported to be superior to the phenotypic methods for identification of those atypical isolates, the specific nonribosomal targets chosen for detection have not been examined for their validity within closely related species. This is primarily because of the absence of database alignments of parallel target genes. Based on information regarding the evolutionary stability of functional genetic markers in the bacterial genomes as well as the availability of a sequence database with significant storage of closely related pseudomonal species in parallel, we chose to examine the gyrB gene sequence for its conformity with the traditional phenotypic gold standard. We examined the P. aeruginosa-specific gyrB primers in 100 phenotypically characteristic strains (25 E1, 25 E2, and 50 H1 strains), 4 species closely related to P. aeruginosa, and 100 oxidase-positive gram-negative isolates that could not be easily ruled in or out as P. aeruginosa by phenotypic methods (50 H2 and 50 H3 isolates). The gyrB-specific PCR (and sequencing for a subset of 13 isolates in the H2 and H3 groups) demonstrated its utility in parallel with the phenotypic gold standard for the first 100 (typical) isolates and demonstrated species selectivity for the second 100 (atypical) isolates.

Thus, in our hands, strains that were less typical could be much more readily identified by real-time PCR. While molecular identification, including gyrB PCR and the sequencing of the 16S-V3 region and gyrB genes, was used as the gold standard for organism identification, the use of real-time PCR with multiple targets was just as accurate and much faster. Sequencing requires up to a day to complete and is very labor-intensive; real-time PCR can be performed in less than 3 h and can be fully automated.

It was not surprising that we did not identify a “signature sequence” without false positives or false negatives among any of the primer pairs tested by real-time PCR. Molecular identification using any single target for PCR amplification potentially suffers from the same polymorphisms that complicate biochemical identification of these organisms. P. aeruginosa has a great deal of phenotypic and genotypic plasticity, particularly in response to the unique microenvironment of the CF lung, where there is decreased mucociliary clearance of bacteria, an inefficient host immune response, compartmentalization of infection because of inspissated secretions, and the presence of antibiotic selective pressure (13).

Although gyrB real-time PCR was used as part of the gold standard for molecular identification and although all of the primer pairs performed well, the use of a single target cannot be recommended. One problem with single-target examination is that, although the entire genome of P. aeruginosa has been sequenced, the genomes of its closest relatives have not. Thus, comparative-genomics information is lacking and potential inter- or intraspecies sequence polymorphisms within the target region are unknown. Simultaneous testing of more than one target controls for potential false-positive or -negative results caused by the limitations of database information. This is similar to the concept that a single biochemical test (or panel of tests) is not accurate enough for identification of P. aeruginosa. In standard identification schema, the results of multiple tests are collated to most precisely identify the organism (10).

A combination of PCR targets is favored for important quality control reasons, as well. The use of multiple target sequences serves as an important analytical control for the PCRs. While it is possible to control for reagent and instrument function by setting up standard positive and negative controls, the possibility of technical problems or operator error cannot be readily assessed unless multiple reactions are used (14).

We conclude that the use of molecular techniques for the identification of atypical P. aeruginosa and other gram-negative nonfermenting organisms is more accurate and time-efficient than standard biochemical testing without being overly costly. At the TDN Resource Center for CF Microbiology and the clinical laboratory at CHRMC, real-time PCR with multiple targets and 16S-V3 sequencing have become the standard methodology for the identification of difficult-to-identify CF pathogens.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by Cystic Fibrosis Foundation support to the TDN Resource Center for CF Microbiology and the CF Research Development Program at the University of Washington.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burns, J. L., J. Emerson, J. R. Stapp, D. L. Yim, J. Krzewinski, L. Louden, B. W. Ramsey, and C. R. Clausen. 1998. Microbiology of sputum from patients at cystic fibrosis centers in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 27:158-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.da Silvo Filho, L. V. F., J. E. Levi, C. N. O. Bento, S. R. T. Da Silvo Ramos, and T. Rozov. 1999. PCR identification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and direct detection in clinical samples from cystic fibrosis patients. J. Med. Microbiol. 48:357-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Vos, D., C. Bouton, A. Sarniguet, P. De Vos, M. Vauterin, and P. Cornelis. 1998. Sequence diversity of the oprI gene, coding for major outer membrane lipoprotein I, among rRNA group I pseudomonads. J. Bacteriol. 180:6551-6556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Vos, D., A. Lim, Jr., J. P. Pirnay, M. Struelens, C. Vandenvelde, L. Duinslaeger, A. Vanderkelen, and P. Cornelis. 1997. Direct detection and identification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in clinical samples such as skin biopsy specimens and expectorations by multiplex PCR based on two outer membrane lipoprotein genes, oprI and oprL. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:1295-1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Vos, D., A. Lim, Jr., P. De Vos, A. Sarniguet, K. Kersters, and P. Cornelis. 1993. Detection of the outer membrane lipoprotein I and its gene in fluorescent and non-fluorescent pseudomonads: implications for taxonomy and diagnosis. J. Gen. Microbiol. 139:2215-2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferroni, A., I. Sermet-Gaudelus, E. Abachin, G. Quesne, G. Lenoir, P. Berche, and J. L. Gaillard. 2002. Use of 16S rRNA gene sequencing for identification of nonfermenting gram-negative bacilli recovered from patients attending a single cystic fibrosis center. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:3793-3797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilligan, P. H. 1991. Microbiology of airway disease in patients with cystic fibrosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 4:35-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kasai, H., K. Watanabe, E. Gasteiger, A. Bairoch, K. Isono, S. Yamamoto, and S. Harayama. 1998. Construction of the gyrB database for the identification and classification of bacteria. Genome Informatics 9:13-21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khan, A. A., and C. E. Cerniglia. 1994. Detection of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from clinical and environmental samples by amplification of the exotoxin A gene using PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:3739-3745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kiska, D. L., and P. H. Gilligan. 1999. Pseudomonas, p. 517-525. In P. R. Murray, E. J. Baron, M. A. Pfaller, F. C. Tenover, and R. H. Yolken (ed.), Manual of clinical microbiology, 7th ed. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 11.Kiska, D. L., A. Kerr, M. C. Jones, J. A. Caracciolo, B. Eskridge, M. Jordan, S. Miller, D. Hughes, N. King, and P. H. Gilligan. 1996. Accuracy of four commercial systems for identification of Burkholderia cepacia and other gram-negative nonfermenting bacilli recovered from patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:886-891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee, D.-H., Y.-G. Zo, and S.-J. Kim. 1996. Nonradioactive method to study genetic profiles of natural bacterial communities by PCR-single-strand-conformation polymorphism. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:3112-3120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oliver, A., R. Canton, P. Campo, F. Baquero, and J. Blazquez. 2000. High frequency of hypermutable Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis lung infection. Science 288:1251-1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qin, X., D. K. Turgeon, B. P. Ingersoll, P. W. Monsaas, C. J. Lemoine, T. Tsosie, L. O. Stapp, and P. M. Abe. 2002. Bordetella pertussis PCR: simultaneous targeting of signature sequences. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 43:269-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saiman, L., J. L. Burns, D. Larone, Y. Chen, E. Garber, and S. Whittier. 2003. Evaluation of MicroScan Autoscan for identification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from cystic fibrosis patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:492-494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shelly, D. B., T. Spilker, E. J. Gracely, T. Coenye, P. Vandamme, and J. J. LiPuma. 2000. Utility of commercial systems for identification of Burkholderia cepacia complex from cystic fibrosis sputum culture. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:3112-3115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song, K. P., T. K. Chan, Z. L. Ji, and S. W. Wong. 2000. Rapid identification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from ocular isolates by PCR using exotoxin A-specific primers. Mol. Cell. Probes 14:199-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Speert, D. P., S. W. Farmer, M. E. Campbell, J. M. Musser, R. K. Selander, and S. Kuo. 1990. Conversion of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to the phenotype characteristic of strains from patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 28:188-194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilson, V. L., B. C. Tatford, X. Yin, S. C. Rajki, M. M. Walsh, and P. LaRock. 1999. Species-specific detection of hydrocarbon-utilizing bacteria. J. Microbiol. Methods 39:59-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamamoto, S., and S. Harayama. 1995. PCR amplification and direct sequencing of gyrB genes with universal primers and their application to the detection and taxonomic analysis of Pseudomonas putida strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:1104-1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]