Abstract

To determine the persistence and spread of antibiotic-resistant strains in Gunma University Hospital, 83 Pseudomonas putida strains (each from a different patient) were isolated from January 1997 through December 2001. Of the 83 strains isolated, 27 were resistant to carbapenems. All 27 produced metallo-β-lactamase and were found to be PCR positive for the blaIMP gene. Most (22 strains) were primarily isolated from the wards (W7 [9 strains] and W4 [8 strains]). Another five blaIMP-positive P. putida strains from wards W7 and W4 were obtained by swabbing around the water pipes. A total of 32 blaIMP-positive P. putida strains were assessed by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) and testing of drug susceptibility to 10 chemotherapeutic agents. Both PFGE and MIC patterns revealed that there were long-term resident strains among inpatients and hospital environments. The blaIMP genes of 22 of 32 strains were all transferable to a recipient strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by conjugation or transformation and conferred resistance to carbapenems and cephems. The blaIMP plasmids were conjugally transmissible among P. aeruginosa strains and mediated resistance to amikacin as well as β-lactams. Ten of the 22 plasmids mediated additional resistance to gentamicin and tobramycin. Plasmids with identical DNA and drug resistance patterns were found in P. putida strains with identical PFGE patterns and with different PFGE patterns. We presumed that P. putida was one of the resident species in inpatients and especially in hospital environments, spreading drug resistance genes via plasmids among P. putida strains and supplying them to more pathogenically important species, such as P. aeruginosa.

Carbapenem-hydrolyzing metallo-β-lactamases, especially IMP-type and VIM-type metallo-β-lactamases, are clinically important, because these enzymes effectively hydrolyze almost all β-lactam antibiotics except monobactams, conferring resistance to penicillins and cephems in addition to carbapenems on pathogenic bacteria (12, 13, 18, 21, 23, 32). Since genes encoding these metallo-β-lactamases (blaIMP and blaVIM) and their variant genes have become easy to detect using the PCR method, dissemination of these genes in clinical isolates has been widely observed in gram-negative bacteria, especially in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other non-glucose-fermenting bacteria (3, 4, 6, 8-10, 26-30, 34, 35). Recently, nosocomial infections of Pseudomonas putida producing VIM-type metallo-β-lactamase were reported in Italy (15). The blaVIM gene was plasmid-borne but was not transferable to either P. aeruginosa or Escherichia coli. We also observed metallo-β-lactamase-producing P. putida strains in Gunma University Hospital, but the responsible gene was blaIMP, not blaVIM, and it was plasmid-borne in most of the isolates. In this paper, we report the existence of multiple-drug-resistant P. putida strains that harbored blaIMP plasmids easily transmissible to P. aeruginosa in Gunma University Hospital.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

A total of 32 imipenem (IPM)-resistant P. putida strains isolated from 1997 to 2001 in Gunma University Hospital were investigated. The isolates consisted of 27 strains from different inpatients and 5 strains from the ward environments.

Laboratory P. aeruginosa strains, rifampin-resistant ML5017 (Ile−, Val−, Lys−, Met−) and rifampin-susceptible PAO4141 (Pro−, Met−), were used for the recipients of plasmids in conjugation or transformation (11, 18).

Media.

Sensitivity test broth and sensitivity disk agar (Nissui Pharmaceutical Co., Tokyo, Japan) were used routinely. A minimum medium M9 agar (16) was used for conjugation experiments.

Antibacterial agents.

The sources of antibacterial agents were as follows: imipenem and amikacin, Banyu Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan; meropenem, Sumitomo Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan; ceftazidime (CAZ), Nippon Glaxo Ltd., Tokyo, Japan; cefepime, Meiji Seika Kaisha, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan; aztreonam, Bristol-Myers Squibb K. K., Tokyo, Japan; piperacillin, Toyama Chemical Co., Ltd., Toyama, Japan; gentamicin and tobramycin, Shionogi and Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan; norfloxacin, Kyorin Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Tochigi, Japan; and rifampin, Daiichi Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan.

Susceptibility tests.

MICs were determined by an agar dilution method with sensitivity disk agar (10). Breakpoint MICs of each drug were according to National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) standards (20).

Detection of metallo-β-lactamase-producing strains.

The disk diffusion test for metallo-β-lactamase production using SMA disks (Eiken, Tokyo, Japan), which measures 2-mercaptopropionic acid inhibition of the enzyme (2), was performed. If necessary, Etest strips (AB BIODISK, Solna, Sweden), which measures the inhibitory effect of metallo-β-lactamase by EDTA (31) were used.

Detection of the metallo-β-lactamase gene blaIMP by PCR.

PCR amplification for detecting blaIMP gene was performed as previously reported (30).

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE).

Genomic DNAs of P. putida strains were prepared in agarose plugs that had been treated with lysozyme and pronase K by using Gene Path reagent kit (Bio-Rad, Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer's protocol. DNA was digested with 25 U of the restriction endonuclease SpeI. The DNA fragments generated were then separated in a 1% agarose gel and were run in Tris-borate-EDTA buffer at 14°C on a pulsed-field apparatus (Gene Path System; Bio-Rad) at 6.0 V/cm for 19.7 h at an angle of 120°, with switching times ranging from 5.3 to 34.9 s.

Conjugation and transformation.

Conjugal transfer of the blaIMP gene from P. putida strains was performed by the membrane filter method (30) using P. aeruginosa ML5017 as the recipient strain. The transconjugants were selected on sensitivity disk agar containing both 8 μg of CAZ and 100 μg of rifampin per ml. The second transfer from ML5017 was performed using PAO4141 as the recipient strain, and transconjugants were selected on M9 agar containing 5 μg of proline, 5 μg of methionine, and 8 μg of CAZ per ml. Transformation experiments with plasmid DNAs from P. putida strains were performed by the chemical method described previously (11). Transformants of ML5017 were selected on sensitivity disk agar containing 8 μg of CAZ per ml. Transconjugants and transformants resistant to CAZ were examined for the blaIMP gene by PCR.

Isolation of plasmid DNA.

Plasmid DNA was isolated by alkaline sodium dodecyl sulfate method using QIAfilter Plasmid Midi kits according to the manufacturer's protocol (QIAGEN K.K., Tokyo, Japan).

RESULTS

Detection of metallo-β-lactamase-producing strains in a hospital.

We isolated 83 P. putida strains from different inpatients of the Gunma University Hospital between January 1997 and December 2001. Twenty-seven IPM-resistant strains from patients and five IPM-resistant P. putida isolates from the ward environment were screened for metallo-β-lactamase production by the disk diffusion method and for the presence of blaIMP gene by PCR. Metallo-β-lactamase was detected and the blaIMP gene was identified in all the above-mentioned 32 IPM-resistant strains.

Isolation background and PFGE patterns of blaIMP-positive P. putida strains.

Of the 27 isolates possessing the blaIMP gene, 22 were isolated from urine, and most of these were from two wards: 9 from ward W7 (internal medicine) and 8 from ward W4 (surgery). Furthermore, strains were isolated from around the water pipes of the two wards: four from ward W7 and one from ward W4.

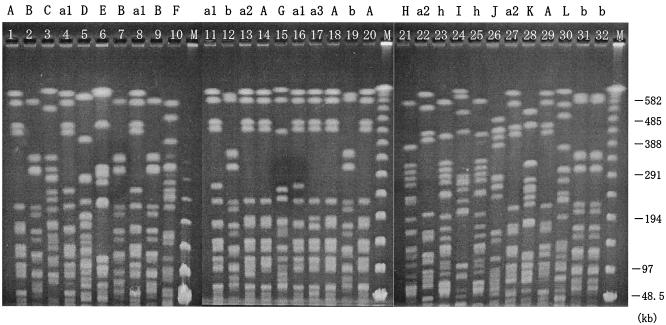

The PFGE patterns of the genomic DNAs digested with SpeI endonuclease are shown in Fig. 1 in chronological order and summarized in Table 1 with the isolation date, the ward and source of the blaIMP-positive P. putida isolates, and the underlying diseases of inpatients from whom strains were isolated. The recurrence of identical PFGE patterns observed in ward W7 suggested that these strains were long-term residents. For example, pattern A was detected in 1997 and 2001 from inpatients and in 2000 from the ward environment. Furthermore, pattern b was detected in 1999 from a patient, in 2000 from the environment in ward W7, and in 2001 from both a patient and the environment in ward W4, evidence suggesting that these strains persisted and spread to different wards.

FIG. 1.

PFGE patterns of SpeI-cut P. putida genomic DNAs are chronologically ordered according to isolation date, and different patterns are indicated by the letters A to L above the gel. Lowercase letters indicate patterns that are almost identical to those with the corresponding capital letter except for one discrepant segment. Numbers added to the small letters indicate different patterns. Strain numbers from 1 to 32 are shown at the top of each lane. M, size markers of DNA bands.

TABLE 1.

P. putida isolates carrying the metallo-β-lactamase gene blaIMP

| Strain | PFGE pattern | Isolation

|

Underlying disease of inpatient | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Datea | Ward | Specimenb | |||

| 1 | A | 1997.03 | W7 | Urine | Prostate cancer |

| 2 | B | 1997.06 | W4 | Urine | Gallbladder carcinoma |

| 3 | C | 1997.06 | W6 | Urine | Pneumonia |

| 4 | a1 | 1997.06 | S6 | Urine | Prostatitis |

| 5 | D | 1997.12 | W3 | Bile | Gallbladder polyps |

| 6 | E | 1997.12 | E2 | Urine | Uterine cancer |

| 7 | B | 1998.08 | S7 | Urine | Renal failure |

| 8 | a1 | 1998.08 | S7 | Urine | Anemia |

| 9 | B | 1998.08 | W7 | Urine | Myeloma |

| 10 | F | 1998.12 | W4 | Urine | Colon cancer |

| 11 | a1 | 1999.03 | S4 | Urine | Brain tumor |

| 12 | b | 1999.06 | W7 | Urine | Leukemia |

| 13 | a2 | 1999.06 | W4 | Urine | Ovarian tumor |

| 14 | A | 1999.10 | W6 | Urine | Myeloma |

| 15 | G | 1999.12 | W7 | Urine | Lymphoma |

| 16 | a1 | 2000.03 | W7 | Urine | Leukemia |

| 17 | a3 | 2000.04 | W7 | Urine | Osteosarcoma |

| 18 | A | 2000.04 | W7 | E | |

| 19 | b | 2000.04 | W7 | E | |

| 20 | A | 2000.04 | W7 | E | |

| 21 | H | 2000.04 | W7 | E | |

| 22 | a2 | 2000.07 | W7 | Feces | Pneumonia |

| 23 | h | 2000.10 | W4 | Urine | Hepatoma |

| 24 | I | 2000.10 | W4 | Bile | Pancreatic cancer |

| 25 | h | 2000.11 | W4 | Urine | Rectal cancer |

| 26 | J | 2000.12 | S7 | Urine | Prostatic hyperplasia |

| 27 | a2 | 2000.12 | W7 | Urine | Aplastic anemia |

| 28 | K | 2000.12 | W4 | Urine | Hepatoma |

| 29 | A | 2001.08 | W7 | Urine | Diabetes mellitus |

| 30 | L | 2001.09 | W3 | Bile | Hepatoma |

| 31 | b | 2001.10 | W4 | Ascitic fluid | Hepatoma |

| 32 | b | 2001.12 | W4 | E | |

Dates are shown with the year before the period and with the month after the period.

E, isolate was from the ward environment.

Drug susceptibility patterns and transferability of the blaIMP gene.

Table 2 shows the isolation ward, drug susceptibility, and transferability of the blaIMP genes of each of the 32 P. putida strains grouped by PFGE patterns.

TABLE 2.

Drug susceptibilities of blaIMP-positive P. putida strains

| PFGE pattern | Strain | Isolation warda | MIC (μg/ml)b

|

Transfer of blaIMPc | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPM | MEM | CAZ | FEP | ATM | PIP | GEN | TOB | AMK | NOR | ||||

| A | 1 | W7 | 32 | >128 | >128 | 64 | 32 | 32 | 64 | 32 | 32 | 128 | − |

| 14 | W6 | 64 | >128 | >128 | 128 | 128 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 128 | − | |

| 18 | W7 (E) | 64 | >128 | >128 | 64 | 32 | 16 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 128 | − | |

| 20 | W7 (E) | 64 | >128 | >128 | 64 | 32 | 32 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 128 | − | |

| 29 | W7 | 64 | >128 | >128 | 64 | 64 | 32 | 128 | 128 | 64 | >128 | + (TF) | |

| a1 | 4 | S6 | 64 | >128 | 128 | 64 | 32 | 16 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 128 | − |

| 8 | S7 | 64 | >128 | >128 | 128 | 16 | 8 | 8 | 16 | 16 | 128 | − | |

| 11 | S4 | 32 | >128 | 128 | >128 | 32 | 32 | 64 | 64 | 32 | 128 | − | |

| 16 | W7 | 128 | >128 | >128 | >128 | 32 | 64 | 128 | 64 | 128 | 128 | − | |

| a2 | 13 | W4 | 128 | >128 | >128 | 32 | 64 | 32 | 64 | 32 | >128 | 128 | + (C) |

| 22 | W7 | 128 | >128 | >128 | >128 | 64 | 32 | 128 | 64 | >128 | 128 | + (C) | |

| 27 | W7 | 128 | >128 | >128 | >128 | 64 | 32 | 128 | 64 | >128 | 128 | + (C) | |

| a3 | 17 | W7 | >128 | >128 | >128 | >128 | 64 | 64 | 128 | 64 | >128 | 128 | + (C) |

| B | 2 | W4 | 64 | >128 | >128 | 64 | 32 | 16 | 2 | <0.5 | 64 | 1 | + (C) |

| 7 | S7 | 64 | >128 | >128 | 128 | 32 | 32 | 2 | <0.5 | 128 | 2 | + (C) | |

| 9 | W7 | 64 | >128 | >128 | 128 | 32 | 16 | 2 | 4 | 64 | 1 | + (TF) | |

| b | 12 | W7 | 128 | >128 | >128 | 64 | 32 | 16 | 2 | 1 | 128 | 1 | + (C) |

| 19 | W7 (E) | 64 | >128 | >128 | 128 | 32 | 16 | 2 | 0.5 | 64 | 1 | + (C) | |

| 31 | W4 | 64 | 64 | >128 | 128 | 32 | 16 | 2 | 0.5 | 128 | 1 | + (C) | |

| 32 | W4 (E) | 64 | 64 | >128 | 128 | 32 | 16 | 2 | 0.5 | 128 | 1 | + (C) | |

| C | 3 | W6 | 16 | 128 | 64 | 64 | 32 | 16 | 2 | 1 | 64 | 1 | + (C) |

| D | 5 | W3 | 64 | >128 | >128 | 64 | 64 | 32 | 128 | 128 | 64 | >128 | + (C) |

| E | 6 | E2 | 16 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 128 | 64 | 8 | 4 | 64 | 2 | − |

| F | 10 | W4 | 32 | >128 | >128 | 64 | 32 | 16 | 8 | 32 | 64 | 32 | + (TF) |

| G | 15 | W7 | 16 | >128 | >128 | >128 | 32 | >128 | 64 | 64 | 128 | 4 | + (TF) |

| H | 21 | W7 (E) | 64 | >128 | >128 | 128 | 32 | 16 | 64 | 32 | 128 | 1 | + (C) |

| h | 23 | W4 | 32 | >128 | >128 | >128 | 32 | 16 | 128 | 64 | >128 | 1 | + (C) |

| 25 | W4 | 64 | >128 | >128 | 64 | 32 | 16 | 128 | 32 | 128 | 1 | + (C) | |

| I | 24 | W4 | 128 | >128 | >128 | >128 | 32 | >128 | 2 | 8 | 32 | 16 | + (C) |

| J | 26 | S7 | 16 | 64 | 128 | 64 | 32 | 16 | 2 | 2 | 32 | 32 | − |

| K | 28 | W4 | 8 | 32 | 32 | 16 | 8 | 8 | 2 | 4 | 32 | 8 | + (C) |

| L | 30 | W3 | 16 | 64 | >128 | >128 | 16 | 8 | 2 | 4 | 16 | 8 | + (C) |

E, environmental isolate.

Drug abbreviations: MEM, meropenem; FEP, cefepime; ATM, aztreonam; PIP, piperacillin; GEN, gentamicin; TOB, tobramycin; AMK, amikacin; NOR, norfloxacin.

Transfer of the blaIMP gene was performed using a recipient of P. aeruginosa strain ML5017 by conjugation (C) or transformation (TF). −, no transfer.

For each strain, MICs of 10 anti-Pseudomonas agents were determined. As defined by NCCLS standards, all 32 strains were highly or intermediately resistant to carbapenems (IPM and meropenem) and cephems (CAZ and cefepime), which are good substrates for IMP-type metallo-β-lactamase, and these strains (except strains 8 and 30) were concomitantly highly or intermediately resistant to amikacin. Furthermore, 13 of 32 strains (strains 1, 14, 18, 20, 29, 4, 11, 16, 13, 22, 27, 17, and 5) were obviously resistant to all drugs tested in this study, that is, carbapenems, cephems, the monobactam aztreonam, aminoglycosides (gentamicin, tobramycin, and amikacin), and the fluoroquinolone norfloxacin, except for the penicillin (piperacillin) whose MIC was not always high. The PFGE patterns of 11 of the 13 strains were restricted to pattern A and its relatives a1, a2, and a3, suggesting the dissemination of strains having a common clonal origin.

Some strains had exactly the same PFGE pattern, drug susceptibility pattern, and blaIMP transferability. Strains 1 (isolated in 1997 from a patient) and 18 (isolated in 2000 from a ward environment) with PFGE pattern A were resistant to multiple anti-Pseudomonas agents and were presumed to be identical strains resident in ward W7. Isolates 22 and 27 with PFGE pattern a2 were also multidrug resistant, and their blaIMP genes were conjugally transmissible. They were isolated in July and December 2000 from different patients in ward W7. Strains 2 and 7 (isolated from different inpatients in different wards in 1997 and 1998, respectively) were indistinguishable in terms of their PFGE pattern (B), drug susceptibility, and presence of transmissible blaIMP gene. Strains 31 and 32 (isolated in 2001 from a patient and the ward environment of W4, respectively) were also indistinguishable in PFGE pattern (b), drug susceptibility, and conjugal transmissibility of the blaIMP gene.

Characterization of transferable plasmids carrying the blaIMP gene.

Transferability of blaIMP genes of P. putida was first examined by conjugation, and for strains whose blaIMP gene was not conjugally transferable, the gene transfer was performed by transformation with extracted DNA. The blaIMP genes of 18 of 32 P. putida strains were transferred to P. aeruginosa strain ML5017 by conjugation. Plasmid DNA was isolated from 5 of the remaining 14 P. putida strains but was not detected in the other 9 strains. Transformation of ML5017 with the blaIMP gene was successful with DNAs from four of above five strains. From transconjugants and transformants of ML5017, the blaIMP gene was transferred by conjugation to a second P. aeruginosa recipient strain (PAO4141) at frequencies of 10−3 to 10−5 per recipient CFU, indicating that the blaIMP genes were all located on the conjugative plasmids.

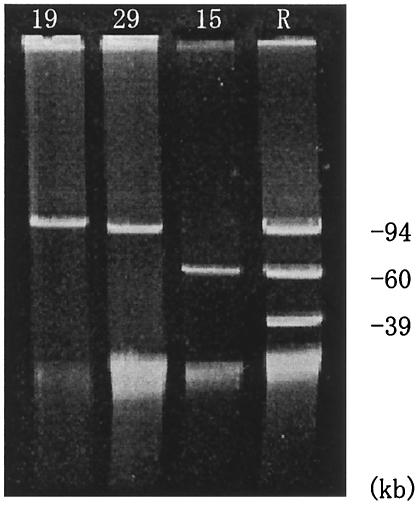

Agarose gel electrophoresis revealed three types of plasmids of ca. 9.8, 9.4, and 60 kb in size. Plasmid DNAs representative of 22 transconjugants or transformants of P. aeruginosa ML5017 are shown in Figure 2.

FIG. 2.

Plasmid DNAs isolated from transconjugants or transformants of P. aeruginosa strains. The numbers at the top of each lane indicate the P. putida strain from which the plasmids were obtained. Lane R contains DNA from reference plasmids R100 (94 kb) (GenBank accession no. AP000342), RP4 (60 kb) (5), and Rsa (39 kb) (5).

The plasmid size and plasmid-mediated drug resistance of P. aeruginosa ML5017 are shown in Table 3. Plasmids with the same size and drug resistance pattern were found to occur in strains (strains 22 and 27, strains 2 and 7, and strains 31 and 32) with the same PFGE pattern and drug susceptibility pattern.

TABLE 3.

Plasmid-mediated drug resistance in P. aeruginosa

| Plasmid | MIC (μg/ml)b

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sourcea | Size (kb) | IPM | MEM | CAZ | FEP | ATM | PIP | GEN | TOB | AMK |

| 29 (A) | 94 | 4 | 32 | 128 | 64 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 16 | 128 |

| 13 (a2) | 94 | 4 | 32 | 128 | 64 | 2 | 4 | <0.5 | <0.5 | 64 |

| 22 (a2) | 94 | 4 | 32 | 128 | 64 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 16 | 32 |

| 27 (a2) | 94 | 4 | 32 | 128 | 64 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 16 | 64 |

| 17 (a3) | 60 | 4 | 32 | 128 | 64 | 2 | 4 | <0.5 | <0.5 | 128 |

| 2 (B) | 94 | 4 | 32 | 128 | 64 | 2 | 4 | <0.5 | <0.5 | 64 |

| 7 (B) | 94 | 8 | 32 | 128 | 64 | 2 | 4 | <0.5 | <0.5 | 64 |

| 9 (B) | 98 | 4 | 32 | 128 | 64 | 2 | 8 | <0.5 | <0.5 | 64 |

| 12 (b) | 98 | 4 | 32 | 128 | 128 | 2 | 4 | <0.5 | <0.5 | 64 |

| 19 (b) | 98 | 4 | 32 | 128 | 64 | 2 | 4 | <0.5 | <0.5 | 64 |

| 31 (b) | 94 | 8 | 32 | 128 | 64 | 2 | 8 | <0.5 | <0.5 | 64 |

| 32 (b) | 94 | 4 | 32 | 128 | 64 | 2 | 4 | <0.5 | <0.5 | 64 |

| 3 (C) | 94 | 4 | 32 | 128 | 64 | 2 | 8 | <0.5 | <0.5 | 32 |

| 5 (D) | 94 | 8 | 32 | 128 | 64 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 8 | 32 |

| 10 (F) | 60 | 4 | 32 | 128 | 64 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 32 |

| 15 (G) | 60 | 4 | 32 | 128 | 64 | 2 | 4 | <0.5 | <0.5 | 128 |

| 21 (H) | 94 | 4 | 32 | 128 | 64 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 16 | 32 |

| 23 (h) | 94 | 4 | 32 | 128 | 64 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 32 |

| 25 (h) | 94 | 4 | 32 | 128 | 64 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 32 |

| 24 (I) | 60 | 4 | 32 | 128 | 64 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 8 | 32 |

| 28 (K) | 94 | 4 | 32 | 128 | 64 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 32 |

| 30 (L) | 60 | 4 | 32 | 128 | 64 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 32 |

| ML5017c | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | 1 | 2 | 1 | <0.5 | <0.5 | 2 | |

Strain number of P. putida with PFGE pattern shown in parentheses.

For drug abbreviations, see Table 2, footnote b.

Host strain of plasmid, i.e., P. aeruginosa ML5017.

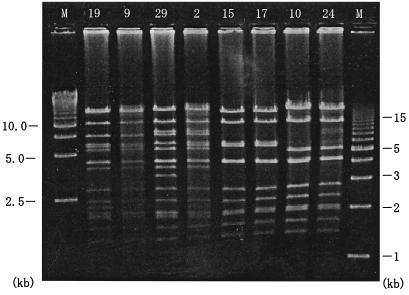

We examined plasmid DNAs using restriction endonuclease EcoRI and compared digestion patterns. Figure 3 shows the representative EcoRI digestion patterns of 8 of the 15 plasmids. The ca. 98-kb plasmids from strains 12 and 19 showed identical DNA pattern and were similar to that from strain 9 with a discrepancy of a small fragment. The 94-kb plasmid DNAs from strains 29, 22, and 27 were identical, and those from strains 13, 2, 7, 31, and 32 were identical. A discrepancy of a small fragment was observed between plasmids from strains 29 and 2. It was shown that plasmids with identical DNA and drug resistance patterns were borne not only in the strains with the same PFGE pattern (a2, B, or b) but also in strains with different PFGE patterns (a2, a3, B, and b) (Table 3). The 60-kb plasmid DNAs from strains 15 and 17 and from strains 10 and 24 showed identical DNA patterns. The PFGE patterns of strains 15 and 17 were G and a3, respectively, but the DNA and drug resistance patterns of the plasmids were indistinguishable. Similarly, the PFGE patterns of strains 10 and 24 were F and I, respectively, and the plasmid DNA and drug resistance patterns were identical. Plasmids with identical sizes and drug resistance patterns were also isolated from strains showing clearly different PFGE patterns. These findings indicated that clonally identical P. putida strains were residing in the same ward or spreading to other wards over time.

FIG. 3.

Plasmid DNAs digested with restriction endonuclease EcoRI. The numbers above each lane are the strains from which the plasmids were obtained. M, size markers (Bio-Rad).

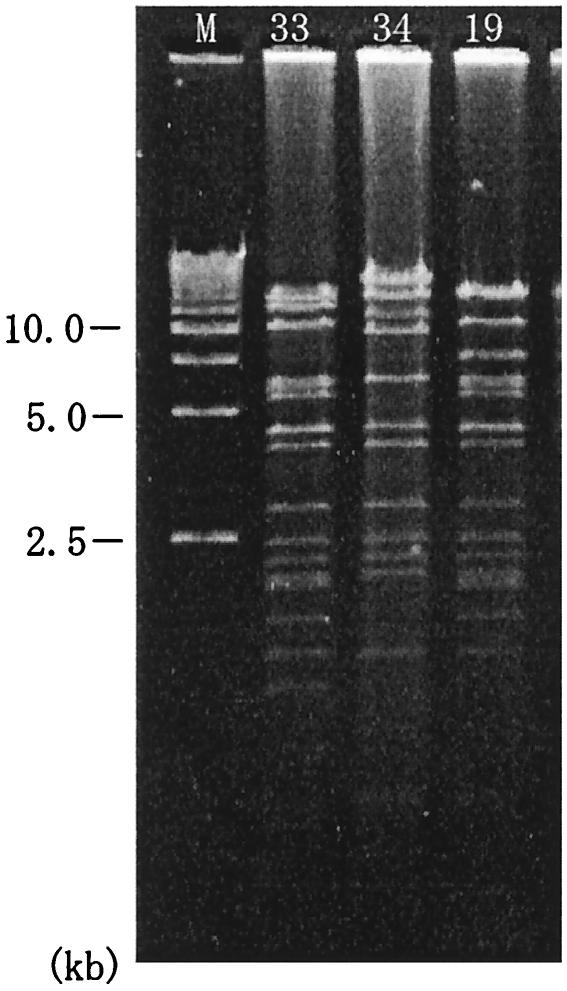

As it seemed interesting that P. putida plasmids were easily transmissible by conjugation to P. aeruginosa, we examined blaIMP-bearing plasmids from P. aeruginosa isolates during the same period. Two plasmids of ca. 98 kb in size were detected in P. aeruginosa strains which were isolated from the ward W7 environment in April 2000 (strain 33) as well as P. putida strain 19 and an inpatient of the ward E1 in March 1999 (strain 34). The drug resistance pattern of the plasmid from strain 33 was the same as that of P. putida strain 19 plasmid but that of strain 34 plasmid was different in amikacin susceptibility. The EcoRI-cut restriction patterns of P. aeruginosa plasmids are shown in Fig. 4 in comparison with that of P. putida strain 19 plasmid. Although P. aeruginosa plasmids were not identical to the P. putida plasmid, robust similarities were observed, especially between strain 33 and strain 19 plasmids.

FIG. 4.

P. aeruginosa plasmid DNAs digested with restriction endonuclease EcoRI. Plasmids 33 and 34 were from P. aeruginosa strains and plasmid 19 was from a P. putida strain. M, size markers (Bio-Rad).

DISCUSSION

P. putida, a species closely related to P. aeruginosa, has low pathogenic potential for most patients, with the exception of immunocompromised patients (1, 25). Over a 5-year period, P. putida strains resistant to carbapenems and many other kinds of chemotherapeutic agents were isolated from 27 inpatients of Gunma University Hospital. All strains of P. putida species that were carbapenem resistant carried the carbapenem-hydrolyzing metallo-β-lactamase gene blaIMP, while 28% of 96 carbapenem-resistant strains of P. aeruginosa during the same period carried blaIMP (data not shown). Other mechanisms which mediate carbapenem resistance were reported in P. aeruginosa. These mechanisms include the following: (i) deficiency of an outer membrane protein, OprD, which is a permeation route of carbapenems through the bacterial outer membrane into the periplasm where the targets of β-lactam antibiotics, penicillin-binding proteins, are located (14, 19); or (ii) efflux pump systems for antibacterial agents including carbapenems (17, 24). These mechanisms have not yet been reported in P. putida species. It was presumed in P. putida strains that mechanisms other than metallo-β-lactamase, if any, contribute to carbapenem resistance only when present in conjunction with metallo-β-lactamase production and that the blaIMP gene may be essential for carbapenem resistance in this species.

Recently, multiple-drug-resistant P. putida isolates producing VIM-type metallo-β-lactamases were reported in Italy as a causative species of nosocomial infections (15). This also means that the metallo-β-lactamase production is an important factor for drug resistance in P. putida species.

Twenty-seven P. putida strains in Gunma University Hospital were all isolated from inpatients with underlying diseases, and 24 of 27 strains were urine and fecal isolates. Furthermore, 22 of 27 strains were isolated together with other bacterial species. These findings suggest that these P. putida strains are not the cause of infection but that they only colonize patients.

Since PFGE analysis of Pseudomonas genomes was first proposed by B. W. Holloway et al. in 1992 (7), there have been a few reports about typing in P. putida species. Genomic analysis using PFGE in a standard P. putida strain was performed (22), and it was reported that PFGE of genomic DNA was a highly discriminatory and reproducible method for epidemiological typing of clinical isolates of P. putida (33).

We revealed a variety of PFGE patterns among P. putida isolates in Gunma University Hospital and applied them to genotyping of hospital strains.

Assuming that strains with identical PFGE patterns, drug susceptibility patterns, and blaIMP plasmids are identical, we could track the dissemination of the same strain within and between wards: intraward transfer (strains 22 and 27 in ward W7, strains 12 and 19 in ward W7, and strains 31 and 32 in ward W4) and interward transfer (strain 2 in ward W4 and strain 7 in specimen S7). Furthermore, the same strains were isolated from inpatients and the ward environments (strains 12 and 19 in ward W7 and strains 31 and 32 in ward W4).

These findings suggest that P. putida has been resident and widespread in Gunma University Hospital for a long time and that its persistence was due to adaptation to the hospital environment.

It was of interest that presumably the same plasmids (with identical phenotypes and genotypes [i.e., same drug resistance pattern and pattern of EcoRI-digested DNA fragments]) were identified in different strains from different hospital wards (i.e., ward W7 or W4). This suggested that plasmid dissemination by conjugal transfer was common among P. putida strains. We confirmed conjugal transferability of the blaIMP gene of these P. putida strains using a laboratory recipient strain of P. putida (data not shown).

Although pathogenicity seems not to be an important factor in P. putida, multiple-drug resistance cannot be disregarded, because it helps P. putida colonize and persist in immunocompromised inpatients, causing nosocomial infections. In addition, it was presumed that the transferable plasmids conferred resistance to multiple anti-Pseudomonas agents on pathogenic P. aeruginosa strains.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anaissie, E., V. Faistein, P. Miller, H. Kassamali, S. Pitlik, G. P. Bodey, and K. Rolston. 1987. Pseudomonas putida, newly recognized pathogen in patients with cancer. Am. J. Med. 82:1191-1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arakawa, Y., N. Shibata, K. Shibayama, H. Kurokawa, T. Yagi, H. Fujiwara, and M. Goto. 2000. Convenient test for screening metallo-β-lactamase-producing gram-negative bacteria by using thiol compounds. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:40-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chu, Y.-W., M. Afzal-Shah, E. T. S. Houang, M.-F. I. Palepou, D. J. Lyon, N. Woodford, and D. M. Livermore. 2001. IMP-4, a novel metallo-β-lactamase from nosocomial Acinetobacter spp. collected in Hong Kong between 1994 and 1998. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:710-714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gibb, A. P., C. Tribuddharat, R. A. Moore, T. J. Louie, W. Krulicki, D. M. Livermore, M.-F. I. Palepou, and N. Woodford. 2002. Nosocomial outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa with a new blaIMP allele blaIMP-7. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:255-258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gotz, A., R. Pukall, E. Smit, E. Tietze, R. Prager, H. Tschape, J. D. van Elsasa, and K. Smalla. 1996. Detection and characterization of broad-host-range plasmids in environmental bacteria by PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:2621-2628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirakata, Y., K. Izumikawa, T. Yamaguchi, H. Takemura, H. Tanaka, R. Yoshida, J. Matsuda, M. Nakano, K. Tomono, S. Maesaki, M. Kaku, Y. Yamada, S. Kamihira, and S. Kohno. 1998. Rapid detection and evaluation of clinical characteristics of emerging multiple-drug-resistant gram-negative rods carrying the metallo-β-lactamase gene blaIMP. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2006-2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holloway, B. W., M. D. Escuadra, A. F. Morgan, R. Saffery, and V. Krishnapillai. 1992. The new approaches to whole genome analysis of bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 100:101-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ito, H., Y. Arakawa, S. Ohsuka, R. Wacharotayankun, N. Kato, and M. Ohta. 1995. Plasmid-mediated dissemination of the metallo-β-lactamase gene blaIMP among clinically isolated strains of Serratia marcescens. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:824-829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iyobe, S., H. Kusadokoro, J. Ozaki, N. Matsumura, S. Minami, S. Haruta, T. Sawai, and K. O'Hara. 2000. Amino acid substitutions in a variant of IMP-1 metallo-β-lactamase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2023-2027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iyobe, S., H. Kusadokoro, A. Takahashi, S. Yomoda, T. Okubo, A. Nakamura, and K. O'Hara. 2002. Detection of a variant metallo-β-lactamase, IMP-10, from two unrelated strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and an Alcaligenes xylosoxidans strain. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:2014-2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iyobe, S., M. Tsunoda, and S. Mitsuhashi. 1994. Cloning and expression in Enterobacteriaceae of the extended-spectrum β-lactamase gene from a Pseudomonas aeruginosa plasmid. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 121:175-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laraki, N., N. Franceschini, G. M. Rossolini, P. Santucci, C. Meunier, E. De Pauw, G. Amicosante, J. M. Frere, and M. Galleni. 1999. Biochemical characterization of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa 101/1477 metallo-β-lactamase IMP-1 produced by Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:902-906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lauretti, L., M. L. Riccio, A. Mazzariol, G. Cornaglia, G. Amicosante, R. Fontana, and G. M. Rossolini. 1999. Cloning and characterization of blaVIM, a new integron-borne metallo-β-lactamase gene from a Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolate. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1584-1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Livingstone, D., M. J. Gill, and R. Wise. 1995. Mechanisms of resistance to the carbapenems. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 35:1-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lombardi, G., F. Luzzaro, J. D. Docquier, M. L. Riccio, M. Perilli, A. Coli, G. Amicosante, G. M. Rossolini, and A. Toniolo. 2002. Nosocomial infections caused by multidrug-resistant isolates of Pseudomonas putida producing VIM-1 metallo-β-lactamase. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:4051-4055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maniatis, T., E. F. Fritsch, and J. Sambrook. 1982. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 17.Masuda, N., E. Sakagawa, S. Ohya, N. Gotoh, H. Tsujimoto, and T. Nishino. 2000. Substrate specificities of MexAB-OprM, MexCD-OprJ, and MexXY-OprM efflux pumps in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:3322-3327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Minami, S., M. Akama, H. Araki, Y. Watanabe, H. Narita, S. Iyobe, and S. Mitsuhashi. 1996. Imipenem and cephem resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa carrying plasmids for class B β-lactamases. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 37:433-444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Minami, S., H. Araki, T. Yasuda, M. Akama, S. Iyobe, and S. Mitsuhashi. 1993. High-level imipenem resistance associated with imipenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamase production and outer membrane alteration in a clinical isolate of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Exp. Clin. Chemother. 6:21-28. [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 1997. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. Approved standard M7-A4. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Villanova, Pa.

- 21.Osano, E., Y. Arakawa, R. Wacharotayankun, M. Ohta, T. Horii, H. Ito, F. Yoshimura, and N. Kato. 1994. Molecular characterization of an enterobacterial metallo-β-lactamase found in a clinical isolate of Serratia marcescens that shows imipenem resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:71-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramos-Diaz, M. A., and J. L. Ramos. 1998. Combined physical and genetic map of the Pseudomonas putida KT2440 chromosome. J. Bacteriol. 180:6352-6363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rasmussen, B. A., and K. Bush. 1997. Carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:223-232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pai, H., J.-W. Kim, J. Kim, J. H. Lee, K. W. Cho, and N. Gotoh. 2001. Carbapenem resistance mechanisms in Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:480-484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palleroni, N. J. 1984. Family I. Pseudomonadaceae Winslow, Broadhurst, Buchanan, Krumwiede, Rogers and Smith 1917, 555AL, p. 141-219. In N. R. Krieg and J. G. Holt (ed.), Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology, vol. 1. Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, Md.

- 26.Poilel, L., T. Naas, D. Nicolas, L. Collet, S. Bellais, J. D. Cavallo, and P. Nordmann. 2000. Characterization of VIM-2, a carbapenem-hydrolyzing metallo-β-lactamase and its plasmid- and integron-borne gene from a Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolate in France. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:891-897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Riccio, M. L., N. Franceschini, L. Boschi, B. Caravelli, G. Cornaglia, R. Fontana, G. Amicosante, and G. M. Rossilini. 2000. Characterization of the metallo-β-lactamase determinant of Acinetobacter baumannii AC-54/97 reveals the existence of blaIMP allelic variants carried by gene cassettes of different phylogeny. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:1229-1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Senda, K., Y. Arakawa, K. Nakashima, H. Ito, S. Ichiyama, K. Shimokata, N. Kato, and M. Ohta. 1996. Multifocal outbreaks of metallo-β-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa resistant to broad-spectrum β-lactams, including carbapenems. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:349-353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Senda, K., Y. Arakawa, S. Ichiyama, K. Nakashima, H. Ito, S. Ohsuka, K. Shimokata, N. Kato, and M. Ohta. 1996. PCR detection of metallo-β-lactamase gene (blaIMP) in gram-negative rods resistant to broad-spectrum β-lactams. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:2909-2913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takahashi, A., S. Yomoda, I. Kobayashi, T. Okubo, M. Tsunoda, and S. Iyobe. 2000. Detection of carbapenemase-producing Acinetobacter baumannii in a hospital. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:526-529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walsh, T. R., A. Bolmstrom, A. Qwarnstrom, and A. Gales. 2002. Evaluation of a new Etest for detecting metallo-β-lactamases in routine clinical testing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:2755-2759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Watanabe, M., S. Iyobe, M. Inoue, and S. Mitsuhashi. 1991. Transferable imipenem resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35:147-151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weng, L. C., G. J. Liaw, N. Y. Wang, S. F. Wang, C. M. Lee, F. Y. Huang, D. I. Yang, and C. S. Chiang. 1999. Investigation of an outbreak of Pseudomonas putida using antimicrobial susceptibility patterns, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of genomic DNA and restriction fragment length polymorphism of PCR-amplified rRNA operons. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 32:187-193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yan, J. J., W. C. Ko, and J. J. Wu. 2001. Identification of a plasmid encoding SHV-12, TEM-1, and a variant of IMP-2 metallo-β-lactamase, IMP-8, from a clinical isolate of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2368-2371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yan, J. J., P. R. Hsueh, W. C. Ko, K. T. Luh, S. H. Tsai, H. M. Wu, and J. J. Wu. 2001. Metallo-β-lactamase in clinical Pseudomonas isolates in Taiwan and identification of VIM-3, a novel variant of the VIM-2 enzyme. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2224-2228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]