Abstract

To determine the effect of the ovarian hormone cycle on immunity, immunoglobulin-secreting cell (ISC) frequency and lymphocyte subsets were examined in the blood of healthy women. We found that immunoglobulin A (IgA)-secreting cells (IgA-ISC) were fourfold more frequent than IgG-ISC in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC). Further, the ISC frequency in PBMC was highest (P < 0.05) during the periovulatory stage of the menstrual cycle. Thus, endogenous ovarian steroids regulate the ISC frequency and this may explain why women are more resistant to viral infections and tend to have more immune-mediated diseases than men do.

The strength and nature of immune responses differ between women and men. Humoral and cellular immune responses in females are stronger than those in males (2). For example, female mice produce stronger antibody and cell-mediated responses to immunization than males do (9, 34). Immunoglobulin M (IgM), but not IgG, levels and CD4/CD8 T-cell ratios are significantly higher in the blood of women than in that of men (1, 19). Women also develop autoimmune diseases at a much higher rate than men do (36). The precise reasons for the observed gender bias in these diseases are unclear; however, it may be related to the generally stronger immune responses of women. These observations clearly demonstrate a role for ovarian steroid hormones in mediation of the immune system.

Gender also influences the clinical course of many viral diseases. Females are more likely to develop a Th1-type response after viral exposure, except during pregnancy, when Th2 responses predominate (36). Female mice are more resistant to lethal vesicular stomatitis virus (3, 12), Coxsackie type B-3 virus (22), herpes simplex virus type 1 (4, 6), and Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (18) infections. Further, in viral infections in which Th1 responses are known to produce immune-mediated pathology, such as lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infections, females have a more severe disease. Clearly, ovarian sex hormones affect the nature and effectiveness of antiviral immunity.

We have demonstrated that the menstrual cycle stage has a dramatic effect on IgG and IgA levels in cervicovaginal secretions of macaques that is similar to the changes found in women (21). Further, in rhesus macaques the frequency of immunoglobulin-secreting cells (ISC) and antibody-secreting cells is significantly higher in systemic lymphoid tissues and the vaginal mucosa collected in the periovulatory period of the menstrual cycle than at other stages of menstrual cycle (20). The change in ISC frequency is not due to a change in the relative frequency of lymphocyte subsets, as this does not change during the menstrual cycle (23).

In the present study, we sought to confirm that cyclic changes in ovarian steroid hormone levels elicit similar changes in the ISC frequency of women. Thus, we determined the frequency of spontaneous IgG-secreting cells (IgG-ISC) and IgA-ISC in the peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) of healthy women volunteers throughout the course of several menstrual cycles. Criteria for participation in the study included an age of 30 to 45 years, no pregnancy at the time of entry into the study, no use of oral or parenteral hormonal contraceptives, no known health problems, hematocrits greater than 37% (normal range, 36 to 47%), and a recent history of regular menstrual cycles. There was no evidence of autoimmune disease, endocrine diseases, heart and vascular diseases, cerebrovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, allergy, gastrointestinal tract and liver diseases, kidney and urinary diseases, or alcohol or drug abuse in any of the volunteers. If a subject became pregnant during the study, she was withdrawn from the study. A urine pregnancy test was done a week prior to the start of the study. All of the women gave informed consent to participate in this study, which was approved by the University of California—Davis Institutional Review Board. Although all of the participants had hematocrits greater than 37% at entry into the study, hematocrit fluctuations occurred during the course of the study. Thus, individual blood samples were excluded if they had a hematocrit lower than 35% or there was evidence of infection, such as neutrophilia or lymphocytosis. Volunteers were also removed from the study if they came under a physician's care for allergy or infections during the course of the study or had a poor follow-up. On the basis of these criteria, six of the nine volunteers completed the study. The ages and hematology data of these six women volunteers at the time of enrollment are listed in Table 1. Peripheral venous blood (40 ml) was collected from each participant twice a week for 14 weeks. A standard multivitamin containing iron was supplied to all participants. PBMC were isolated by differential gradient centrifugation as previously described (20). A single midday voided urine sample was collected on Monday to Friday with a sterile collection cup and transferred to 15-ml conical centrifuge tubes. The urine samples were stored at −20°C within 15 min of collection and subsequently used to assess systemic levels of ovarian hormones. Daily urinary levels of estrone conjugates, pregnanediol-3-glucuronide, and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) β subunit of all women were measured by enzyme immunoassay as previously described (21, 28).

TABLE 1.

Ages and hematology data of the subjects at enrollment

| Subject or parameter | Age (yr) | Hematocrit (%) | WBC count (103/μl)a | No. of lymphocytes/μl |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E01 | 45 | 40.7 | 8.6 | 37 |

| E04 | 34 | 41.2 | 5.3 | 40 |

| E05 | 33 | 40.8 | 6.8 | 25 |

| E06 | 31 | 37.6 | 8.5 | 29 |

| E07 | 30 | 37.8 | 5.3 | 31 |

| E08 | 39 | 37.8 | 8.8 | 36 |

| Normal range | 36-47 | 4.8-10.8 | 25-38 |

WBC, white blood cell.

Complete blood cell counts and three-color flow cytometry were performed on each fresh heparinized venous blood sample by a licensed medical technician. Anti-CD3+-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), anti-CD4+-phycoerythrin (PE), anti-CD8+-peridinin chlorophyl protein (PerCP), anti-CD20+-PerCP, and anti-CD56+-PE were obtained from B-D Biosciences/PharMingen, San Jose, Calif. The three-color staining combinations used were as follows: PE-CD4, PerCP-CD8, and FITC-CD3 in one tube and FITC-CD3, PerCP-CD20, and PE-CD56 in the other tube. Numbers of CD4+, CD8+, CD20+, and CD56+ cells were determined with a FACScalibur flow cytometer (Becton-Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, Calif.). Data were analyzed with FlowJo versions 3.6 and 4.1 (TreeStar, San Carlos, Calif.). The ISC frequency in blood was enumerated by ELISPOT assay as previously described, with the exception that anti-human immunoglobulin was used as a detection reagent (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Inc., Birmingham, Ala.) (20).

ISC isotype frequency in blood.

As has previously been reported in rhesus monkeys (20) and humans (14), the frequency of IgA-ISC in PBMC was fourfold higher than the frequency of IgG-ISC (5.75 ± 0.47 IgG-ISC/105 PBMC versus 24.52 ± 2.08 IgA-ISC/105 PBMC; P < 0.05). Similar results were obtained when the data were analyzed to determine the number of ISC per 105 lymphocytes or the number of ISC per 105 B cells (19.40 ± 2.24 IgG-ISC/105 lymphocytes versus 82.64 ± 8.48 IgA-ISC/105 lymphocytes; P < 0.05; 30.25 ± 2.42 IgG-ISC/105 B cells versus 149.45 ± 14.50 IgA-ISC/105 B cells; P < 0.05) (Table 2). The frequencies of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, eosinophils, CD20+ B cells, and CD56 + NK cells in all of the samples from the women were in the normal range (11, 17, 24, 25, 33) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

ISC frequencies and other PBMC parameters of six normal women during the 3-month study

| Parameter | No. of sample | ISC frequency

|

Percentilesa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SE | Median | |||

| No. of IgG-ISC/105 lymphocytes | 106 | 19.4 ± 2.2 | 12.8 | 8.6-20.0 |

| No. of IgG-ISC/105 PBMC | 106 | 5.8 ± 0.5 | 4.0 | 3.0-6.0 |

| No. of IgG-ISC/105 B cells | 105 | 30.2 ± 2.4 | 21.7 | 15.6-33.9 |

| No. of IgA-ISC/105 lymphocytes | 106 | 82.6 ± 8.5 | 60.1 | 35.3-86.7 |

| No. of IgA-ISC/105 PBMC | 106 | 24.5 ± 2.1 | 16.0 | 12.0-28.0 |

| No. of IgA-ISC/105 B cells | 106 | 149.5 ± 14.5 | 103.5 | 69.4-175.7 |

| No. of CD4+ T cells/μl | 106 | 1,192.9 ± 52.9 | 1,129.0 | 783.0-1,449.0 |

| No. of CD8+ T cells/μl | 106 | 643.9 ± 24.4 | 613.5 | 444.0-766.0 |

| CD4+/CD8+ cell ratio | 105 | 1.9 ± 0.04 | 1.7 | 1.6-2.1 |

| WBC count (103/μl)b | 105 | 8.3 ± 0.2 | 8.5 | 6.8-9.9 |

| % Lymphocytes | 105 | 34.6 ± 1.1 | 33.0 | 26.0-43.0 |

| No. of lymphocytes/μl | 105 | 2,880.8 ± 124.7 | 2,664.0 | 1,866.0-3,365.2 |

| % Monocytes | 78 | 4.4 ± 0.3 | 4.0 | 2.0-6.0 |

| No. of monocytes/μl | 78 | 365.8 ± 26.5 | 308.0 | 204.0-468.0 |

| % CD20+ B cells gated | 104 | 19.8 ± 0.6 | 19.8 | 15.9-24.5 |

| No. of CD20+ B cells/μl | 104 | 603.4 ± 38.8 | 472.5 | 290.5-790.5 |

| % CD56+ cells gated | 103 | 5.0 ± 0.3 | 4.7 | 2.8-6.4 |

| No. of CD56+ cells/μl | 104 | 141.2 ± 11.1 | 118.5 | 64.0-167.0 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 105 | 42.9 ± 3.6 | 39.2 | 37.1-41.7 |

The 25th to 75th percentiles are shown.

WBC, white blood cells.

Effect of menstrual cycle stage on ISC frequency.

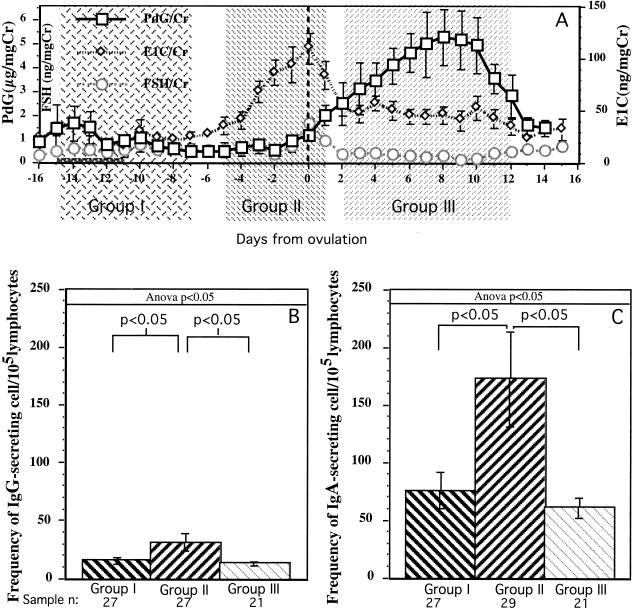

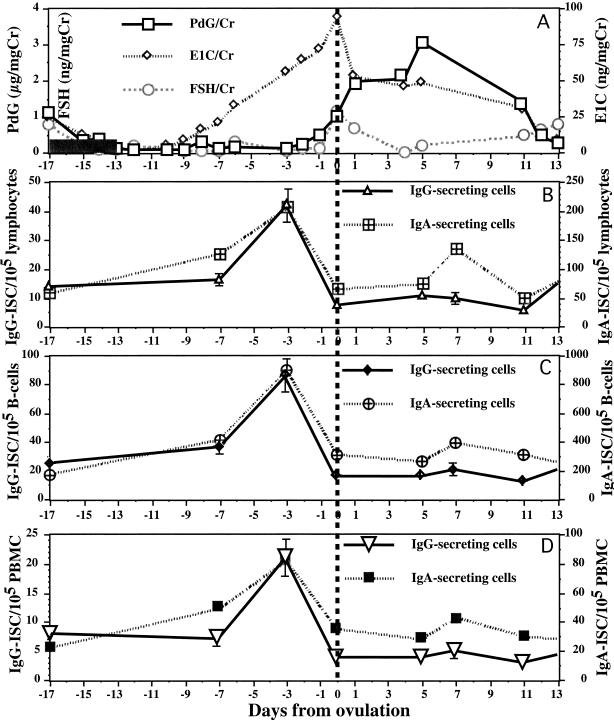

Blood samples were collected twice a week, and the sampling period extended over two or three complete menstrual cycles. The inability to collect weekend urine samples made it difficult to be certain of the day of ovulation in some individuals. To be certain that samples were placed into the correct groups for comparisons, only the data from one or two of the best-characterized menstrual cycles of each woman were included in the analysis. Group I included 27 samples collected between menstrual cycle days −15 and −7 (Fig. 1). Thus, group I samples were collected over a 9-day period in the follicular phase, when the levels of both progesterone (PdG) and estrogen (E1C) were relatively low. Group II included 27 samples collected between menstrual cycle days −5 and 1. Thus, group II samples were collected over a 7-day period in the periovulatory stage, when E1C levels were high and PdG levels were low. Group III included 21 samples collected between menstrual cycle days 2 and 12. Thus, group III samples were collected over an 11-day period in the luteal phase, when PdG levels were high and E1C levels were low to moderate. Only the samples collected during menstrual cycles in which we could document a normal PdG and E1C pattern (as show in Fig. 1A) were included in the analysis. The frequency of IgG- and IgA-ISC in the PBMC samples collected during the follicular (group I), periovulatory (group II), and luteal (group III) phases were compared by Duncan's new multiple-range statistical method (Fig. 1B and C). The frequency of IgG-ISC in group II PBMC samples was significantly higher than that in group I (P < 0.025) and group III (P < 0.016) PBMC samples (Fig. 1B). Similar results were found for IgA-ISC; the frequency of IgA-ISC in group II PBMC samples was significantly higher than that in group I (P < 0.016) and group III (P < 0.01) samples (Fig. 1C). Thus, the frequency of ISC in PBMC samples collected during the periovulatory stage was significantly higher than that in PBMC samples collected at other stages of the menstrual cycle. Representative results from an individual subject are illustrated in Fig. 2. Note that the increased frequency of ISC in blood was apparent when either the total number of lymphocytes, PBMC, or B cells were used as the denominator. Thus, as has been shown previously in female rhesus monkeys (23), the changes in ISC frequency were not due to altered frequencies in other cell populations. The in vivo effect of ovarian hormones on ISC frequency in women is consistent with published findings demonstrating the enhancing effect of E1Cs on the differentiation of human antibody-secreting cells in vitro (10, 26, 31).

FIG. 1.

Comparison of frequencies of ISC in PBMC. To compare the effects of steroid hormones on ISC frequency, each PBMC sample from six women with normal menstrual cycles was assigned to one of three groups based on daily urine PdG, E1C, and FSH levels. (A) Mean (± standard error) urinary levels of PdG (pregnanediol-3-glucuronide), E1C (estrone conjugates), and FSH are shown on separate y axes. The means of PdG, E1C, and FSH were generated from the samples of three to six women that were collected on the same menstrual cycle day. The day of ovulation (dashed vertical line) was designated day 0 and occurred on the day of the peak FSH and E1C levels in urine. The menstrual cycles of the women were aligned around the day of ovulation. Menses occurred from day −15 to day −11. The shaded portions of the figure denote different sample groups. Group I includes samples collected in the 9 days from day −15 to day −7 of the menstrual cycle. Group II includes samples collected in the 7 days from day −5 to day 1 of the menstrual cycle. Group III includes samples collected in the 11 days from day 2 to day 12 of the menstrual cycle. (B) Frequency of IgG-ISC per 105 lymphocytes. (C) Frequency of IgA-ISC per 105 lymphocytes. Each bar represents the mean ISC frequency plus the standard error. Single-factor analysis of variance (Anova) was used to assess the significance of any differences among the groups. If the analysis of variance revealed a significant difference (P < 0.05), then Duncan's new multiple-range post-hoc test was used in a pairwise comparison of groups to determine if the difference between the means of two groups was statistically significant at the 95% confidence level. The P values for Duncan's new multiple-range test are shown at the top.

FIG. 2.

Frequencies of IgG- and IgA-ISC in a normal menstrual cycle of a representative subject. (A) Hormone levels in urine during the menstrual cycle. Mean urinary levels of PdG, E1C, and FSH are shown on separate y axes. The day of ovulation (dashed vertical line) was designated day 0. Menses occurred from day −17 to day −13 (shaded bars). (B) Numbers of IgG- and IgA-ISC per 105 lymphocytes shown on separate y axes. (C) Numbers of IgG- and IgA-ISC per 105 B cells. (D) Numbers of IgG- and IgA-ISC per 105 PBMC.

Physiological levels of estrogen stimulate, while physiological levels of PdG depress, B-cell maturation in both human and nonhuman primate PBMC cultures (10, 20, 26, 31). In rhesus monkeys, the frequencies of ISC and antibody-secreting cells in genital tract tissues and numerous systemic lymphoid tissues are significantly affected by the stage of the menstrual cycle (20). To date, there have been no reports establishing an in vivo role for ovarian steroids in the regulation of B-cell function in normal women. In the present study, we show that the frequency of ISC in PBMC of normal women was affected significantly by the stage of the menstrual cycle in a manner very similar to that described in female rhesus monkeys.

Note that in Fig. 2, the peak estrogen level in urine was not coincident with the highest ISC frequency in most of the cases. The ISC frequency peak occurred 2 days before the E1C level peak in urine. Presumably, this discordance exists because hormone levels in urine reflect the levels in serum on the previous day (8, 10).

E1C stimulates immunoglobulin-secreting activity by B cells in PBMC, and estrogen receptors are found on human macrophage lines (15), human CD8-positive peripheral T cells (7, 32), stromal cells derived from bone marrow of mice (29, 30), and mouse splenic lymphocytes (27). Estrogen stimulates interleukin-1 (IL-1) production by macrophages, and IL-1 levels in the plasma of women increase after ovulation (5, 16). Further, IL-1 can serve as either a B-cell growth factor or differentiation factor (13). Among human T cells, estrogen receptors are present only in T cells of the CD8+ suppressor/cytotoxic subset (32). Further, the effect of estrogen and progesterone on rhesus monkey B-cell physiology in vitro is mediated indirectly through CD8+ T cells (20). Thus, it is likely that B-cell immunity in women is regulated by CD8+ T cells under the influence of ovarian steroid hormones.

Elucidation of the precise cellular and molecular mechanisms by which sex hormones alter immune function is vital to understanding gender-based differences in autoimmunity (35, 36). Further, it has been difficult to elicit vaccine-induced protective immunity to sexually transmitted diseases in women. A better understanding of the role of sex hormones in promoting antibody secretion by B cells may lead to improved therapies for autoimmune diseases and vaccine strategies for the control of sexually transmitted diseases, including AIDS, in women.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants P51 RR 60169; R01 HD 33169, and U 54HD 125.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amadori, A., R. Zamarchi, G. De Silvestro, G. Forza, G. Cavatton, G. A. Danieli, M. Clementi, and L. Chieco-Bianchi. 1995. Genetic control of the CD4/CD8 T-cell ratio in humans. Nat. Med. 1:1279-1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ansar, A. S., W. J. Penhale, and N. Talal. 1985. Sex hormones, immune responses and autoimmune diseases. Am. J. Pathol. 121:531-551. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barna, M., T. Komatsu, Z. Bi, and C. S. Reiss. 1996. Sex differences in susceptibility to viral infection of the central nervous system. J. Neuroimmunol. 67:31-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouley, D. M., S. Kanangat, W. Wire, and B. T. Rouse. 1995. Characterization of herpes simplex virus type-1 infection and herpetic stromal keratitis development in IFN-γ knockout mice. J. Immunol. 155:3964-3971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cannon, J. G., and C. A. Dinarello. 1985. Increased plasma interleukin-1 activity in women after ovulation. Science 227:1247-1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cantin, E. M., D. R. Hinton, J. Chen, and H. Openshaw. 1995. Gamma interferon expression during acute and latent nervous system infection by herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Virol. 69:4898-4905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen, J. H., L. Danel, G. Cordier, S. Saez, and J. P. Revillard. 1983. Sex steroid receptors in peripheral T cells: absence of androgen receptors and restriction of estrogen receptors to OKT8-positive cells. J. Immunol. 131:2767-2771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dawson, E. B., J. E. Simmons, and M. Nagamani. 1983. A comparison of serum free estriol with spontaneous urine total estrogen and estrogen/creatinine ratio. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 21:371-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eidinger, D., and T. J. Garret. 1972. Studies of the regulatory effects of the sex hormones on antibody formation and stem cell differentiation. J. Exp. Med. 136:1098-1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evans, J. J., and M. Legge. 1983. The use of plasma or early morning urine specimens for monitoring estrogen in non-pregnant women. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 6:379-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finnegan, K. 1998. Hematopoiesis, p. 833-869. In C. A. Lehmann (ed.), Saunders manual of clinical laboratory science, 1st ed. The W. B. Saunders Company, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 12.Forger, J. M., III, R. T. Bronson, A. S. Huang, and C. S. Reiss. 1991. Murine infection by vesicular stomatitis virus: initial characterization of the H-2d system. J. Virol. 65:4950-4958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gallagher, G., N. Taylor, J. Willdridge, J. F. Christie, and W. H. Stimson. 1988. Responses of human B-cells to recombinant lymphokines. Dev. Biol. Stand. 69:65-73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gudmundsson, K. O., L. Thorsteinsson, S. Gudmundsson, and A. Haraldsson. 1999. Immunoglobulin-secreting cells in cord blood: effects of Epstein-Barr virus and interleukin-4. Scand. J. Immunol. 50:21-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gulshan, S., A. B. McCruden, and W. H. Stimson. 1990. Oestrogen receptors in macrophages. Scand. J. Immunol. 31:691-697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu, S. K., Y. L. Mitcho, and N. C. Rath. 1988. Effect of estradiol on interleukin 1 synthesis by macrophages. Int. J. Immunopharmacol. 10:247-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Janssen, W. C., and J. J. Hoffmann. 1999. Three-colour, one-tube flow cytometric method for enumeration of CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 36:196-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kappel, C. A., R. W. Melvold, and B. S. Kim. 1990. Influence of sex on susceptibility in the Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus model for multiple sclerosis. J. Neuroimmunol. 29:15-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lichtman, M. A., J. H. Vaughan, and C. G. Hames. 1967. The distribution of serum immunoglobulins, anti-gamma-G globulins (“rheumatoid factors”) and antinuclear antibodies in White and Negro subjects in Evans County, Georgia. Arthritis Rheum. 10:204-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lü, F. X., K. Abel, Z. Ma, T. Rourke, D. Lu, J. Torten, M. McChesney, and C. J. Miller. 2002. The strength of B cell immunity in female rhesus macaques is controlled by CD8+ T cells under the influence of ovarian steroid hormones. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 128:10-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lü, F. X., Z. Ma, T. Rourke, S. Srinivasan, M. McChesney, and C. J. Miller. 1999. Immunoglobulin concentrations and antigen-specific antibody levels in cervicovaginal lavages of rhesus macaques are influenced by the stage of the menstrual cycle. Infect. Immun. 67:6321-6328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lyden, D. C., and S. A. Huber. 1984. Aggravation of coxsackievirus, group B, type 3-induced myocarditis and increase in cellular immunity to myocyte antigens in pregnant BALB/c mice and animals treated with progesterone. Cell. Immunol. 87:462-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma, Z., F. X. Lü, M. Torten, and C. J. Miller. 2001. The number and distribution of immune cells in the cervicovaginal mucosa remain constant throughout the menstrual cycle of rhesus macaques. Clin. Immunol. 100:240-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marti, G. E., L. Magruder, K. Patrick, M. Vail, W. Schuette, R. Keller, K. Muirhead, P. Horan, and H. R. Gralnick. 1985. Normal human blood density gradient lymphocyte subset analysis. I. An interlaboratory flow cytometric comparison of 85 normal adults. Am. J. Hematol. 20:41-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mendes, R., K. V. Bromelow, M. Westby, J. Galea-Lauri, I. E. Smith, M. E. O'Brien, and B. E. Souberbielle. 2000. Flow cytometric visualisation of cytokine production by CD3− CD56+ NK cells and CD3+ CD56+ NK-T cells in whole blood. Cytometry 39:72-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paavonen, T., L. C. Anderson, and H. Adlercreutz. 1981. Sex hormone regulation of in vitro immune response: estradiol enhances human B cell maturation via inhibition of suppressor T cells in pokeweed mitogen-stimulated cultures. J. Exp. Med. 154:1935-1945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sakazaki, H., H. Ueno, and K. Nakamuro. 2002. Estrogen receptor alpha in mouse splenic lymphocytes: possible involvement in immunity. Toxicol. Lett. 133:221-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shideler, S. E., N. A. Gee, J. Chen, and B. L. Lasley. 2001. Estrogen and progesterone metabolites and follicle-stimulating hormone in the aged macaque female. Biol. Reprod. 65:1718-1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smithson, G., J. F. Couse, D. B. Lubahn, K. S. Korach, and P. W. Kincade. 1998. The role of estrogen receptors and androgen receptors in sex steroid regulation of B lymphopoiesis. J. Immunol. 161:27-34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smithson, G., K. Medina, I. Ponting, and P. W. Kincade. 1995. Estrogen suppresses stromal cell-dependent lymphopoiesis in culture. J. Immunol. 155:3409-3417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sthoeger, Z. M., N. Chiorazzi, and R. G. Lahita. 1988. Regulation of the immune response by sex hormones. I. In vitro effects of estradiol and testosterone on pokeweed mitogen-induced human B-cell differentiation. J. Immunol. 141:91-98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stimson, W. H. 1988. Estrogen and human T lymphocytes: presence of specific receptors in the T suppressor/cytotoxic subset. Scand. J. Immunol. 28:345-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Storek, J., M. A. Dawson, and D. G. Maloney. 1998. Comparison of two flow cytometric methods enumerating CD4 T cells and CD8 T cells. Cytometry 33:76-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weinstein, Y., S. Ran, and S. Segal. 1984. Sex-associated differences in the regulation of immune responses controlled by the MHC of the mouse. J. Immunol. 132:656-661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Whitacre, C. C. 2001. Sex differences in autoimmune disease. Nat. Immunol. 2:277-280. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Whitacre, C. C., S. C. Reingold, and P. A. O'Looney. 1999. A gender gap in autoimmunity. Science 283:1277-1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]