Abstract

TonB, in complex with ExbB and ExbD, is required for the energy-dependent transport of ferric siderophores across the outer membrane of Escherichia coli, the killing of cells by group B colicins, and infection by phages T1 and φ80. To gain insights into the protein complex, TonB dimerization was studied by constructing hybrid proteins from complete TonB (containing amino acids 1 to 239) [TonB(1-239)] and the cytoplasmic fragment of ToxR which, when dimerized, activates the transcription of the cholera toxin gene ctx. ToxR(1-182)-TonB(1-239) activated the transcription of lacZ under the control of the ctx promoter (Pctx::lacZ). Replacement of the TonB transmembrane region by the ToxR transmembrane region resulted in the hybrid proteins ToxR(1-210)-TonB(33-239) and ToxR(1-210)-TonB(164-239), of which only the latter activated Pctx::lacZ transcription. Dimer formation was reduced but not abolished in a mutant lacking ExbB and ExbD, suggesting that these complex components may influence dimerization but are not strictly required and that the N-terminal cytoplasmic membrane anchor and the C-terminal region are important for dimer formation. The periplasmic TonB fragment, TonB(33-239), inhibits ferrichrome and ferric citrate transport and induction of the ferric citrate transport system. This competition provided a means to positively screen for TonB(33-239) mutants which displayed no inhibition. Single point mutations of inactive fragments selected in this manner were introduced into complete TonB, and the phenotypes of the TonB mutant strains were determined. The mutations located in the C-terminal half of TonB, three of which (Y163C, V188E, and R204C) were obtained separately by site-directed mutagenesis, as was the isolated F230V mutation, were studied in more detail. They displayed different activity levels for various TonB-dependent functions, suggesting function-related specificities which reflect differences in the interactions of TonB with various transporters and receptors.

Active import of substrates, such as siderophores and vitamin B12, and sensitivity of cells to certain phages and group B colicins are mediated by outer membrane transport proteins which also serve as receptor proteins. In addition, the required energy is provided by the proton motive force of the cytoplasmic membrane (2), along with an energy-transducing device in the cytoplasmic membrane which is composed of the TonB, ExbB, and ExbD proteins (3, 22, 37). The N terminus of TonB (residues 13 to 32) anchors it to the inner membrane, while most of the protein is located in the periplasm, where it interacts with outer membrane transporters (7, 15, 35, 40). The topography of ExbD resembles that of TonB (23), whereas ExbB spans the cytoplasmic membrane three times, with most of the protein being located in the cytoplasm (24). TonB, ExbB, and ExbD seem to form a complex, but its stoichiometry is unknown. Under iron-replete conditions, the copy number of the TonB, ExbB, and ExbD proteins per cell was found to be approximately 335:2,463:741 (1:7:2) (20); however, these ratios may not reflect the ratios of the proteins in the predicted complex. The TonB, ExbB, and ExbD proteins interact with each other mainly through their membrane-embedded regions (1, 4, 6, 11, 28, 30). Cross-linking with formaldehyde yielded ExbB and ExbD homodimers and homotrimers whose formation did not depend on the presence of TonB (19). Recently, the carboxyl-terminal fragment of TonB from amino acids 164 to 239 [TonB(164-239)] was crystallized and shown to be a dimer (9). In contrast, sedimentation experiments and size exclusion chromatography of the periplasmic TonB(33-239) fragment yielded mostly the monomeric form (34). Therefore, we determined by an in vivo method whether TonB and TonB fragments form monomers, dimers, or multimers and whether dimerization, if it occurs, depends on the presence of ExbBD.

In addition, we isolated TonB point mutants to localize functionally important sites outside the cytoplasmic membrane domain and to determine whether a lack of activity is related to TonB homodimerization. We took advantage of a previous study in which it was shown that TonB fragments which were lacking the cytoplasmic membrane anchor were transported into the periplasm via the FecA signal sequence. These fragments inhibited the transport of ferrichrome by the FhuA transporter and of ferric citrate by the FecA transporter, FecA-dependent transcriptional induction of the fecABCDE ferric citrate transport genes, infection by phage φ80, and cell killing by colicin M; phage φ80 and colicin M both bind to FhuA (21). In the present study, this inhibition by TonB fragments was used to select for mutated TonB fragments which no longer inhibited TonB-related functions. Random mutagenesis of the gene encoding the periplasmic TonB fragment resulted in point mutants that could grow again on ferric citrate as a sole iron source. The point mutations were cloned into the complete low-copy-number tonB gene, and the mutants were tested for their ability to support the transport of ferric citrate and ferrichrome and the sensitivity of cells to phage φ80 and colicin M.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The Escherichia coli strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

E. coli strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| DH5α | Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 endA1 recA1 hsdR17(rK− mK+) supE44 thi-1 gyrA1 relA1 (F′ φ80 ΔlacZΔM15) | 16 |

| AB2847 | aroB malT tsx thi | 5 |

| H2300 | AB2847 Δ(tonB-trp) | This study |

| FHK12 | F′ lacIqlacZΔM15 proA+B+ara Δ(lac-proAB) rpsL (φ80 ΔlacZΔM15) attB::(ctx::lacZ) Ampr | 27 |

| ASA23 | FHK12 ΔexbBD | This study |

| ZI418 | fecB::Mud1X (Ap lac) aroB Δ(argF-lac)U169 araD139 rpsL150 relA1 flbB5301 deoC1 ptsF25 rbsR thi | 45 |

| AS418 | ZI418 tonB | This study |

| CO93 | ZI418 Δfec tonB | 17 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pHKToxR′PhoA | pHK toxR′(1-210)-phoA Cmr | 27 |

| pHKToxR′MalE | pHK toxR′(1-210)-malE Cmr | 27 |

| pTRFRTMC | pHK toxR(1-182)-fecR(83-317) Cmr | S. Enz |

| pASAToxRTonB1 | pHK toxR(1-182)-tonB(1-239) Cmr | This study |

| pASAToxR′TonB33 | pHK toxR(1-210)-tonB(33-239) Cmr | This study |

| pASAToxR′TonB164 | pHK toxR(1-210)-tonB(164-239) Cmr | This study |

| pWKS30 | 2.3-kb fragment from pBCIIKS + 3.1-kb PvuI/SalI fragment from pLG339; Ampr | 46 |

| pCAR109 | pCVD442 derivative; NotI/SalI insert; suicide vector; Kanr | C. R. Osorio |

| pCH709 | pT7-7 exbBD Ampr | C. Herrmann |

| pASA27 | pACYC184 exbBD Tetr | This study |

| pMalP2 | ColE1 ori malE Ampr | NEB |

| pMal-c2G | ColE1 ori malE Ampr | Gibco-BRL |

| pHSG576 | pSC101 derivative; Cmr | 42 |

| pGEM-T-Easy | pGEMR-5Zf(+) derivative; Ampr | Promega |

| pCSTon30 | pET30a(+) tonB Kanr | 21 |

| pAS1 | pMFTC ΔtonB(33-239)-cat′; 14-bp linker from pCSTon30; Ampr | This study |

| pCG752 | pT7-5 tonB Ampr | 11 |

| pMFTC | pMal-c2G tonB(33-239) Ampr Cmr | 21 |

| pASTM163 | pMal-c2G tonB(33-239); Y163C Ampr Cmr | This study |

| pASTM188 | pMal-c2G tonB(33-239); V188E Ampr Cmr | This study |

| pASTM204 | pMal-c2G tonB(33-239); R204C Ampr Cmr | This study |

| pASTM230 | pMal-c2G′tonB(33-239); F230V Ampr Cmr | This study |

| pAS2 | pHSG576 tonB Cmr | This study |

| pAST163 | pHSG576 tonB; Y163C Cmr | This study |

| pAST188 | pHSG576 tonB; V188E Cmr | This study |

| pAST204 | pHSG576 ′tonB; R204C Cmr | This study |

| pAST230 | pHSG576 tonB; F230V Cmr | This study |

| pAS3 | pT7-7 fecABCDE Ampr | This study |

| pASAToxRTonBY163C | pHK toxR(1-182)-tonB; Y163C Cmr | This study |

| pASAToxRTonBV188E | pHK toxR(1-182)-tonB; V188E Cmr | This study |

| pASAToxRTonBR204C | pHK toxR(1-182)-tonB; R204C Cmr | This study |

| pASAToxRTonBF230V | pHK toxR(1-182)-tonB; F230V Cmr | This study |

Media and growth conditions.

The media used were tryptone-yeast extract (TY) medium and nutrient broth (NB; Difco) supplemented with 1 mM citrate and, when required, with 40 μg of ampicillin/ml, 20 μg of chloramphenicol/ml, 15 μg of tetracycline/ml, or 50 μg of kanamycin/ml. Cells were grown at 37°C.

Construction of plasmids.

In general, plasmids were constructed by PCR amplification of DNA fragments with appropriate primer pairs, the sequences of which are available upon request. Convenient restriction sites were introduced and used to clone the fragments into restriction-digested vectors. To fuse various regions of TonB in frame with the ToxR(1-210) transmembrane protein (27), plasmid pHKToxR′TonB33 [TonB(33-239)] was created by replacing the EcoRV/XbaI fragment encoding the nondimerizing MalE protein in pHKToxR′MalE with the soluble C-terminal region of wild-type TonB [TonB(33-239)] in pCG752. Plasmid pHKToxR′TonB164 was constructed by replacing the MalE-encoding region of pHKToxR′MalE with a fragment encoding wild-type TonB(164-239). Plasmid pASAToxRTonB1 was constructed by replacing the PmlI/XbaI fragment of plasmid pTRFRTMC with full-length wild-type TonB, thus replacing the transmembrane region of ToxR with that of chromosomal TonB of E. coli AB2847.

Plasmid pASA27 was constructed by cleavage of plasmid pACYC184 with EcoRI/ScaI and ligation with the EcoRI/PstI-digested exbBD gene fragment of plasmid pCH709. The PstI overhang was digested by treatment with the Klenow enzyme before ligation.

Plasmid pAS1 was constructed by removing the ′tonB-cat′ fragment of plasmid pMFTC (21) by restriction digestion with BamHI/NcoI. This fragment was replaced by a 14-bp BamHI/NcoI polylinker of vector pCSTon30.

For cloning of wild-type tonB in the low-copy-number vector pHSG576, PCR-amplified tonB of plasmid pCG752 was cloned into pGEM-T-Easy, which then was digested with XmaI/HindIII. The XmaI-HindIII-tonB fragment was inserted into XmaI/HindIII-digested vector pHSG576, yielding pAS2.

For the construction of plasmid pASTM230, BamHI/NcoI sites were introduced by PCR into fragments of vector pMFTC and cloned into BamHI/NcoI-digested vector pMFTC.

Plasmids pAST163, pAST188, pAST204, and pAST230 were obtained by cloning SgrAI/HindIII-digested point-mutated tonB fragments of plasmids pASTM163, pASTM188, pASTM204, and pASTM230, respectively, into SgrAI/HindIII-digested vector pAS2.

For the construction of plasmid pAS3, the fecABCDE fragment was amplified by PCR from chromosomal DNA of strain AB2847, digested with BamHI/SalI, and cloned into BamHI/SalI-digested vector pT7-7. The resulting plasmid as well as the original PCR product was then digested with SalI/HindIII and ligated.

For the construction of plasmids pASAToxRTonBY163C, pASAToxRTonBV188E, pASAToxRTonBR204C, and pASAToxRTonBF230V, PCR products of plasmids pAST163, pAST188, pAST204, and pAST230, respectively, were cleaved with PmlI/XbaI and cloned into PmlI/XbaI-digested plasmid pTRFRTMC.

Plasmid pMFTC was used as the source for wild-type tonB fragments, unless indicated otherwise. All plasmid constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Construction of strains.

To construct the exbBD knockout mutant ASA23, chromosomal DNA of E. coli AB2847 was amplified by PCR such that a fragment resulted which, by use of a NotI/SalI fragment, could be cloned into NotI/SalI-digested shuttle vector pWKS30. The NotI/SalI insert of pWKS30 was cloned into NotI/SalI-digested suicide vector pCAR109, resulting in plasmid pASAexbBDdel. Conjugation with donor S17-1 λpir(pASAexbBDdel) and recipient FHK12 was done as described by Heinrichs and Poole (18). Selection plates contained ampicillin and kanamycin. To remove the suicide vector, the conjugants were plated on TY plates containing ampicillin and 10% sucrose. Only colonies without sacB are able to survive on these plates. One colony was picked, and the deletion was confirmed by PCR and sequencing.

To construct the chromosomal tonB mutant strain AS418, a mixture containing 10 μl each of colicin B and phage φ80 was spotted onto TY agar plates overlaid with 3 ml of TY soft agar that contained 0.1 ml of an overnight culture of E. coli ZI418. Spontaneous tonB mutant colonies that grew in the area of growth inhibition were tested for resistance to albomycin, colicin M, and phage φ80. One colony was picked and named AS418.

Recombinant DNA techniques.

Standard techniques (38) or the protocols of suppliers were used for the isolation of plasmid DNA, PCR, digestion with restriction endonucleases, ligation, transformation, and agarose gel electrophoresis. DNA was sequenced by MWG, Ebersberg, Germany, with the dideoxy chain termination method.

ToxR-based activation assay.

The various constructs of TonB fused to the toxR gene product were transformed into strain FHK12 or ASA23, which carries the chromosomal ToxR-regulated ctx promoter-lacZ fusion (Pctx::lacZ). Fusion proteins consisting of the N terminus of ToxR and the transmembrane region and periplasmic C terminus of dimerizing PhoA (pHKToxR′PhoA) or nondimerizing MalE (pHKToxR′MalE) were used as controls. The formation of dimers was monitored by the determination of β-galactosidase activity (27). Transformants carrying plasmids encoding different ToxR-TonB fusion proteins were grown overnight in NB. The cultures were 100-fold diluted and further incubated in NB for approximately 3 h in the presence or absence of 1 mM sodium citrate.

Random mutagenesis of the tonB gene.

Random mutagenesis of the tonB gene was carried out by PCR (12). The reaction mixture was composed of 0.1 μg of DNA from plasmid pMFTC (21) containing the tonB sequence; 2 nmol of each primer (TMup and TMdown); 0.2 mM each nucleotide (setup 1), 0.2 mM each dGTP, dTTP, and dCTP and 0.05 mM dATP (setup 2), or 0.2 mM each dATP, dGTP, and dTTP and 3.4 mM dCTP (setup 3); 1.5 mM MgCl2 (setup 1 and setup 2) or 4.2 mM MgCl2-0.5 mM MnCl2 (setup 3); and 1 U of Taq polymerase in reaction buffer (Promega, Mannheim, Germany).

Screening for tonB mutants.

Mutagenized tonB fragments were cloned into the BamHI/NcoI sites of plasmid pMFTC or vector pAS1. Transformants of E. coli AB2847 were selected on NB plates supplemented with 250 μM dipyridyl, 1 mM sodium citrate, 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), and chloramphenicol. Colonies that grew on the plates were collected, and plasmid DNA was isolated and sequenced.

Phenotype assays.

All phenotype assays were performed with freshly transformed E. coli K-12 strains AB2847 and H2300. The sensitivity of cells to FhuA ligands (phages T1, T5, and φ80; colicin M; microcin J25; and albomycin) was tested by spotting 4 μl of various dilutions (see Table 3) on TY agar plates overlaid with 3 ml of TY soft agar that contained 0.1 ml of a TY overnight culture of the strain to be tested.

TABLE 3.

Growth of E. coli H2300 ΔtonB transformants with ferric citrate or ferrichrome as a sole iron source and fecB-lacZ induction of tonB point mutants

| Expressed protein | Growth ona:

|

fecB-lacZ transcriptionb in:

|

Sensitivity toc:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ferric citrate at:

|

Ferrichrome at 1 mM | NB | NB + citrate | Colicin M | Phage φ80 | ||

| 1 mM | 10 mM | ||||||

| Wild type | 9 | 17 | 28 | 49 | 535 | 3 | 5 |

| No TonB | — | — | — | 17 | 55 | R | R |

| TonB(Y163C) | — | 8 | 30 | 19 | 89 | R | 5 |

| TonB(V188E) | — | 11 | 29 | 23 | 217 | R | 5 |

| TonB(R204C) | — | 13 | 29 | 18 | 429 | 2 | 5 |

| TonB(F230V) | — | — | — | 27 | 48 | R | R |

Growth was measured as the diameter in millimeters of the growth zone around 6-mm filter paper disks which had been saturated with 10 μl of the indicated solutions. Values in italic type show weak growth; those in bold type show weaker growth; —, no growth.

fecB-lacZ transcription was determined with E. coli AS418 fecB-lacZ tonB transformants that expressed the listed TonB proteins. Values are reported in Miller units.

The results of the sensitivity assays are presented as the last of 10-fold dilution series that resulted in a clear zone of lysis. R, resistance to the tested ligand.

Growth promotion was tested by placing filter paper disks containing 10 μl of various ferrichrome and sodium citrate concentrations on NB-250 μM dipyridyl agar plates overlaid with 3 ml of NB soft agar that contained 0.1 ml of an NB overnight culture of the strain to be tested. The diameter and the growth density around the filter paper disks were determined after overnight incubation. The assays were performed at least three times, and the results varied less than 10%.

Induction of the fec transport gene operon by ferric citrate.

The induction of the fec operon by citrate in growth medium was assayed with strains ZI418 (45) and AS418 (this study) transformed with plasmids containing different tonB mutants. Cultures were grown in NB medium supplemented with 1 mM IPTG and 1 mM sodium citrate. AS418 cultures were grown as described before but without IPTG. β-Galactosidase activity was determined as described by Miller (32) and Giacomini et al. (14).

Transport assays.

Quantitative transport of [55Fe3+]ferrichrome and [55Fe3+]citrate was determined as described previously (26). The assays were done with E. coli K-12 strains freshly transformed with the plasmids to be tested.

RESULTS

TonB dimers.

To examine TonB dimer formation in vivo, a bacterial two-hybrid system was used. ToxR of Vibrio cholerae spans the cytoplasmic membrane and as a dimer acts as a transcriptional activator of the cholera toxin gene ctx (10, 33). The periplasmic dimerizing portion of ToxR can be replaced by a dimerizing periplasmic protein such as alkaline phosphatase which, as a ToxR-PhoA hybrid protein, activates the transcription of lacZ under the control of the ctx promoter (Pctx::lacZ) (27, 33, 39). ToxR fused to the periplasmic monomeric MalE binding protein does not activate Pctx::lacZ transcription (27). This system is therefore suitable for examining the dimerization of the periplasmic portion of wild-type and mutant TonB.

The TonB(33-239) and TonB(164-239) fragments, lacking the cytoplasmic membrane anchor, were fused to ToxR(1-210) and expressed in E. coli FHK12 Pctx::lacZ. ToxR(1-210)-PhoA(27-472) and ToxR(1-210)-MalE(27-397) were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. In addition, cells were grown in the presence and absence of 1 mM citrate, since TonB may preferentially bind to FecA loaded with ferric citrate, as has been found for ferrichrome binding to FhuA (34, 35) and ferric enterobactin binding to FepA (41). Binding to ferric citrate-loaded FecA may change the conformation of TonB and affect dimer formation. ToxR(1-210)-TonB(33-239) yielded a β-galactosidase activity that was somewhat lower than the activity induced by ToxR(1-210)-MalE(27-397) but much lower than the activity induced by ToxR(1-210)-PhoA(27-472) (Table 2). In contrast, ToxR(1-210)-TonB(164-239) induced a rather high β-galactosidase activity. Citrate did not affect these values. The data therefore provide evidence that TonB(33-239) has only a slight tendency to form dimers, whereas TonB(164-239) has a high propensity for dimer formation.

TABLE 2.

β-Galactosidase activity of E. coli strains in response to ToxR dimer formation of ToxR(1-210) and ToxR(1-182) hybrid proteinsa

| Protein | β-Galactosidase activity in Miller units (%) in the following E. coli strain:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| FHK12 Pctx::lacZ | ASA23 ΔexbBD Pctx::lacZ | FHK12 Pctx::lacZ with pASA27 exbBD | |

| ToxR(1-210)-PhoA(27-472) | 790 (100) | 914 (100) | 629 (100) |

| ToxR(1-210)-MalE(27-397) | 161 (20) | 209 (23) | 148 (24) |

| ToxR(1-182)-TonB(1-239) | 619 (78) | 433 (47) | 473 (75) |

| ToxR(1-210)-TonB(33-239) | 145 (18) | 174 (19) | 167 (27) |

| ToxR(1-210)-TonB(164-239) | 637 (81) | 660 (72) | 395 (63) |

| ToxR(1-182)-TonB(Y163C) | 916 (116) | 969 (106) | ND |

| ToxR(1-182)-TonB(V188E) | 758 (96) | 814 (89) | ND |

| ToxR(1-182)-TonB(R204C) | 822 (104) | 777 (85) | ND |

| ToxR(1-182)-TonB(F230V) | 1,020 (129) | 1,042 (114) | ND |

The assays were done with NB. Percentages are the average of three independent experiments with a standard deviation of ±9. ND, not determined.

The above experiments might have failed to demonstrate TonB dimer formation if the transmembrane region of TonB were important for dimerization. Therefore, complete TonB was fused to the cytoplasmic portion of ToxR which is represented by residues 1 to 182, which are followed by the transmembrane region spanning residues 183 to 198 in the native protein. ToxR(1-182)-TonB(1-239) activated Pctx::lacZ transcription (Table 2). This experiment showed that the transmembrane region was important for the dimer formation of full-length TonB. Whether dimer formation depended on the presence of ExbB and ExbD was also examined. The ASA23 exbB exbD deletion mutant was constructed and transformed with plasmids encoding hybrid proteins. Dimer formation by complete TonB and TonB(164-239) was reduced, and the lack of dimer formation by TonB(33-239) was unaffected by the exbB exbD deletions (Table 2). Whether the overexpression of exbB exbD affected Pctx::lacZ transcription was tested with an E. coli FHK12 transformant which contained plasmid-carried exbB exbD (pASA27) in addition to chromosomally carried exbB exbD. The overexpression of exbB exbD did not greatly influence dimer formation by ToxR(1-182)-TonB(1-239) or ToxR(1-210)-TonB(164-239), nor did it alter the lack of dimer formation by ToxR(1-210)-TonB(33-239) (Table 2).

Point mutations in inhibitory periplasmic TonB fragments restore TonB-dependent growth on ferric citrate.

The inhibition of chromosomally encoded wild-type TonB activity by plasmid-carried periplasmic TonB fragments provides a means to positively select for TonB mutant fragments which are no longer inhibitory. Among the isolated mutant fragments should be mutations which impair TonB function when cloned into complete TonB. Furthermore, if TonB fragments compete with the binding of TonB to outer membrane transport proteins, then the mutated fragments may not restore the various outer membrane transport systems to the same degree and the mutations cloned in TonB may not affect all TonB-related activities in the same way. By this means, distinct interactions between TonB and currently unknown transporters may be identified.

TonB(33-239) fused to the signal sequence of FecA was secreted into the periplasm and inhibited all tested FecA- and FhuA-related functions. fecA′-′tonB was located on plasmid pMFTC under lac control, a scenario which allowed transcription to be induced by IPTG (21). The tonB fragment was randomly mutagenized by PCR and recloned into pMFTC by replacement of the wild-type TonB fragment or into plasmid pAS1, which contains a convenient BamHI/NcoI polylinker. E. coli AB2847, which does not synthesize a siderophore, was transformed with plasmids carrying the mutagenized tonB fragments, and the transformants were spread on NB agar plates supplemented with 250 μM dipyridyl to restrict the available iron and 1 mM sodium citrate, which complexes a portion of the iron and makes it available to AB2847. The transcription of fecA′-′tonB was induced with 1 mM IPTG. Under these conditions, the wild-type TonB(33-239) fragment inhibited growth.

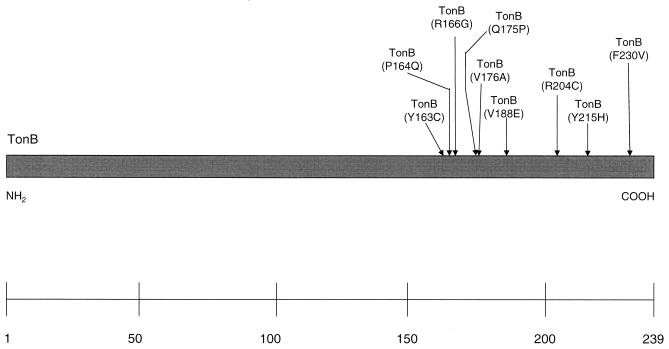

Plasmids were isolated from colonies which appeared on the selection plates, used to confirm the phenotype by retransformation of the host strain, and sequenced. Thirty mutants which synthesized TonB fragments in amounts similar to that of the wild-type TonB fragment, as revealed by Western blotting (data not shown), were isolated. Nine mutants did not synthesize TonB fragments and, for this reason, did not interfere with wild-type TonB activity. They probably contained nonsense mutations. The tonB gene fragments (′tonB) of mutants that expressed TonB fragments were sequenced. Ten mutants contained a single mutation, and the rest contained two or more mutations. Most of the mutations were clustered in the C-terminal third of TonB, as shown for the single mutations in Fig. 1. Further growth tests revealed that the mutated TonB fragments affected growth on ferric citrate and ferrichrome to different extents.

FIG. 1.

Distribution of single mutations in TonB.

Four single TonB mutant fragments with strong phenotypes are described further here. These include ′TonB(Y163C), which contained an additional silent mutation, ′TonB(V188E), and ′TonB(R204C), all of which were isolated in the PCR experiments, and TonB(F230V), which was not selected by the fragment screening procedure but was constructed by site-directed mutagenesis as described previously (M. Anton, A. Bruske, and K. J. Heller, 3rd Int. Symp. Iron Transport, Storage Metab., poster, 1992). ′TonB(Y163C) and ′TonB(F230V) did not inhibit chromosomally encoded wild-type TonB of AB2847 in the transport of ferric citrate, since the transformants grew even at the lowest citrate concentration, whereas transformants containing ′TonB(V188E) and ′TonB(R204C) could grow only at 10 mM citrate. A lack of growth around the filter paper loaded with 1 mM citrate was not caused by a lack of fec transport gene transcription, since chromosomally carried fecB-lacZ of E. coli ZI418 was transcribed in the presence of all mutated TonB fragments.

E. coli AB2847 synthesizing the ′TonB(V188E) and ′TonB(F230V) fragments grew at 1 mM ferrichrome, whereas the other two transformants showed no growth. Sensitivities to colicin M and phage φ80 were tested as additional FhuA-related activities. The sensitivity of the transformants to colicin M was restored to the level of E. coli AB2847 carrying vector pMalP2 (titer, 103), except for the ′TonB(R204C) transformant, which yielded a turbid growth inhibition zone at a 10−3 dilution of colicin M solution. Sensitivity to phage φ80 was also restored to the wild-type level (titer, 106) in E. coli AB2847 synthesizing ′TonB(Y163C) and E. coli AB2847 synthesizing ′TonB(V188E), whereas E. coli AB2847 synthesizing ′TonB(F230V) formed turbid plaques at the 10−6 dilution of the phage suspension and E. coli AB2847 synthesizing ′TonB(R204C) still inhibited wild-type TonB (a very turbid inhibition zone at a 10−3 dilution of the phage suspension).

Insertion of the point mutations into complete TonB yields TonB derivatives that fail to support growth on ferric citrate.

The four single mutations described above were cloned by DNA fragment exchange into the low-copy-number plasmid pAS2, which carries the complete tonB gene. E. coli H2300 ΔtonB was transformed with the mutant plasmids, and growth promotion around filter paper disks loaded with 1 and 10 mM solutions of ferric citrate was tested with iron-limited NB-250 μM dipyridyl plates. The tonB mutants did not grow on ferric citrate (Table 3). To examine whether the failure to grow on ferric citrate was caused by a lack of fec transport gene transcription, E. coli AS418 fecB-lacZ tonB was transformed with the mutated tonB plasmids, and β-galactosidase activity was measured after 3 h of growth with and without ferric citrate in NB. TonB(F230V) supported no induction, TonB(Y163C) supported a low level of induction, TonB(V188E) supported an intermediate induction level, and TonB(R204C) supported a high induction level (Table 3). It thus appears that less TonB activity is required for induction than for transport of ferric citrate.

All of the TonB mutants, except for E. coli H2300 ΔtonB expressing TonB(F230V), supported growth around filter paper disks loaded with 1 mM ferrichrome. Since a 1 mM concentration of ferrichrome may be too high for this assay, testing was repeated with 0.01, 0.03, 0.1, and 0.3 mM ferrichrome. E. coli H2300 ΔtonB expressing TonB(R204C) and E. coli H2300 ΔtonB expressing TonB(Y163C) grew around disks impregnated with 0.01 mM ferrichrome, whereas the growth of E. coli H2300 ΔtonB expressing TonB(V188E) and E. coli H2300 ΔtonB expressing TonB(F230V) around these disks was barely evident (data not shown).

Transport of ferric citrate and ferrichrome into TonB mutant cells.

The semiquantitative growth promotion data were further substantiated by quantitative transport data. The transport of [55Fe3+]citrate and [55Fe3+]ferrichrome was determined with E. coli H2300 ΔtonB (Table 4). TonB(F230V) was not able to transport ferric citrate, whereas TonB(R204C), TonB(V188E), and TonB(Y163C) supported ferric citrate transport; the level of transport correlated with the degree of induction, as determined by β-galactosidase activity expressed by the fecB-lacZ reporter gene (Table 3).

TABLE 4.

Transport rates for the tonB point mutants

| Plasmid | TonB mutation | Rate of transport ofa:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 55Fe3+ citrate into E. coli H2300 ΔtonB | [55Fe3+] ferrichrome into E. coli H2300 ΔtonB | [55Fe3+] citrate into E. coli CO93 ΔfecIRABCDE tonB with pAS3 fecABCDE | ||

| pAS2 | Wild type | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| pHSG576 | No TonB | 6 | 0 | ND |

| pAST163 | Y163C | 14 | 52 | 19 |

| pAST188 | V188E | 24 | 2 | 19 |

| pAST204 | R204C | 34 | 47 | ND |

| pAST230 | F230V | 5 | 2 | 10 |

The rates were calculated by subtracting the values measured after 1 min of incubation, which represent mainly binding, from the values measured after 26 min and are relative to wild-type values (100%). ND, not determined.

Since the lack of induction mediated by TonB(F230V) (Table 3) could have caused a lack of transport, the E. coli CO93 ΔfecIRABCDE tonB mutant was transformed with plasmid pAS3, which carried the fecABCDE transport genes on the pT7-7 medium-copy-number plasmid. The synthesis of FecABCDE proteins from this plasmid without induction is sufficient to support ferric citrate transport. E. coli CO93(pAS3) transformed with pAS2-carried tonB (wild type) transported ferric citrate. Transformants carrying mutated tonB on pAST230, pAST163, or pAST188 displayed 10 to 19% the transport rates of wild-type tonB transformants, indicating that the TonB mutations affected both transport and induction by FecA, both of which were most strongly reduced for the TonB(F230V) mutant.

TonB(R204C) and TonB(Y163C) transported [55Fe3+] ferrichrome, but TonB(V188E) was transport inactive, as was TonB(F230V). The latter results correlate with the results of the competition experiments with the ′TonB fragments, in which ′TonB(V188E) and ′TonB(F230V) no longer inhibited wild-type TonB function. The latter mutations thus abolished the interference of the TonB fragments with the interaction of TonB with outer membrane transporters and also inactivated full-length TonB.

The TonB point mutant proteins remain dimerization competent.

The full-length TonB mutant proteins were fused to ToxR(1-182), and the activation of Pctx::lacZ transcription by the ToxR dimer was determined. The TonB mutant proteins yielded high β-galactosidase activity, which exceeded the activity of wild-type TonB (Table 2). The same result was obtained with the exbB exbD deletion mutant (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

The studies described here provide evidence that TonB can form homodimers and that dimer formation is not dependent on but is influenced by the cosynthesis of ExbB and ExbD. The evidence is based on the TonB-mediated dimer formation of cytoplasmic ToxR, which activates Pctx::lacZ transcription only in the dimeric form. This finding does not necessarily predict the presence of TonB dimers in the complex with ExbB and ExbD but demonstrates the self-association of TonB. It is possible that TonB multimers exist in the complex and that a rather large complex is formed in association with ExbB and ExbD, for which an association with TonB and the existence of homodimers and homotrimers have been demonstrated (19). The specificity of TonB dimer formation was shown by the requirement for the TonB N terminus in the cytoplasmic membrane, which could not be replaced by the transmembrane region of ToxR. Spontaneous disulfide cross-linked TonB dimers were also formed in vivo when single cysteine residues were introduced at position 160 of TonB (7, 8, 36). This result suggests that the ToxR approach did not yield artifacts. Rather, it supports the in vivo relevance of the crystal data, which demonstrated a dimeric TonB(164-239) fragment (9). This fragment must have a strong propensity to form dimers, since both hybrid proteins with ToxR(1-182) and ToxR(1-210) activated Pctx::lacZ transcription. Since the TonB point mutants were not affected in their ability to activate Pctx::lacZ transcription, a lack of dimer formation was not the cause of their selective inactivity in the transport of ferrichrome and ferric citrate, ferric citrate induction, phage infection, and colicin killing. The TonB mutant hybrid proteins displayed an even stronger activation of Pctx::lacZ transcription than did the TonB wild-type hybrid protein. This finding was particularly evident with the exbB exbD deletion mutant, in which the mutant proteins showed a transcription level twofold higher than that of wild-type TonB. It is possible that during the reaction cycle, TonB dissociates into monomers; if so, the affinity of the mutant proteins may be too great for TonB polypeptide separation, thus trapping it in an inactive dimer.

Both the N-proximal and the C-proximal regions of TonB mediate the dimerization of TonB. The dimerization of only complete TonB was reduced in the exbBD deletion mutant, consistent with an interaction of the N-proximal region with ExbB (28).

Although TonB(164-239) forms a dimer in vivo when fused to ToxR(1-210) and in vitro in the crystal structure (9), there was no evidence of dimer formation by ToxR(1-210)-TonB(33-239). It thus seems that a region between residues 33 and 164 prevents dimer formation. The inhibition of dimer formation is abolished, however, in complete TonB, in which the N-terminal region spans the cytoplasmic membrane. Either the transmembrane region also forms a dimer and adds to the dimer formation of complete TonB or complete TonB assumes a conformation different from that of TonB(33-239) and prevents the inhibition of dimer formation by a region between residues 33 and 164. Results similar to these were obtained with the TolA protein, which is structurally and functionally similar to TonB in the TolAQR system. The C-terminal fragment of TolA, called TolAIII, consisting of the last 132 residues of the 421-residue protein, forms a dimeric crystal structure very similar to that of TonB(164-239), but solution X-ray scattering indicates a monomeric structure for the TolII-TolIII fragment, which encompasses the entire periplasmic TolA structure and is equivalent to TonB(33-239) (47). In addition, TolAIII has been fused to the N1 domain of the minor coat gene 3 protein (g3p) of phage M13 via a flexible linker. TolA is required for infection of E. coli by M13 and, during this process, TolIII replaces the N2 domain of g3p. However, the crystal structure of the N1-TolIII hybrid protein contains a TolIII monomer with the same fold as that in the TolAIII dimer (31). In this case, g3p prevents dimer formation by TolIII.

Previously, Howard et al. provided evidence that the inhibition of wild-type TonB activity by the overexpressed TonB(33-239) fragment was most likely caused by competition for binding to FecA and FhuA (21) and not by competition with the binding of TonB to ExbB and ExbD, since the overexpression of FhuA but not the overexpression of ExbBD reversed the inhibition. In this study, we showed that ExbBD did not strongly influence dimer formation. Thus, although TonB(33-239) did not form dimers and, as argued above, seems to prevent dimer formation, it does not appear likely that it inhibits activity by interfering with TonB dimer formation.

A spectrum of phenotypes was displayed by the TonB C-terminal missense mutants. For example, TonB(V188E) displayed 41% ferric citrate induction compared to wild-type TonB and 24% wild-type ferric citrate transport activity but only 2% ferrichrome transport activity. Conversely, TonB(Y163C) showed low fecB transcription (17%) and low ferric citrate transport (14%) but rather high ferrichrome transport (52%). Distinct effects of the TonB mutations were also observed with respect to sensitivities to colicin M and phage φ80, in that the TonB(Y163C) and TonB(V188E) mutants were colicin M resistant but fully phage sensitive. It should also be noted that in contrast to the low activity of TonB(Y163C) in ferric citrate induction and transport, this mutant fully supported growth on vitamin B12 and transport of vitamin B12 (7, 8).

Differential effects of TonB mutations on colicin and phage sensitivities were observed previously. Infection by phage φ80 and, even more clearly, by phage T1 still took place in certain TonB mutants which had lost other TonB-dependent activities. For example, mutants expressing TonB(G186D), obtained by bisulfite mutagenesis, showed strong reductions in most TonB-related activities, except for sensitivity to phage T1, which was unaffected (44). TonB(G186S) conferred full sensitivity to phages T1 and φ80, conferred a 10-fold reduction in sensitivity to colicins B and M, strongly impaired growth on ferrichrome, and resulted in no growth on the fungal siderophore coprogen. TonB(G174R,V178I) conferred resistance to colicin Ia but sensitivity to colicin B, whereas Serratia marcescens TonB conferred sensitivity to colicin B but resistance to colicin Ia in an E. coli tonB mutant (13, 43). Some of the TonB mutants, when combined with certain FhuA point mutants, increased or decreased sensitivity to phage T5 up to 1,000-fold, although T5 does not require TonB to infect cells (25). These data make it clear that interactions of TonB with outer membrane transporters and presumably also with colicins show protein-specific features. The mutations are also located in the C-terminal half of TonB, like the Tyr215 amber mutation which, when suppressed by tRNAs resulting in nine amino acid substitutions, resulted in distinct phenotypes with regard to sensitivities to colicins B, Ia, and M and phage φ80 (29).

In summary, the data presented here suggest that TonB forms homodimers and contains both N-proximal and C-proximal dimerization domains. In addition, the mutations in the TonB C-proximal region described here reduce TonB activity but not by preventing dimerization.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Enz for useful advice and helpful discussions.

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grants BR 330/19-1 and BR 330/19-2) and by a grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada to S.P.H.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmer, B. M., M. G. Thomas, R. A. Larsen, and K. Postle. 1995. Characterization of the exbBD operon of Escherichia coli and the role of ExbB and ExbD in TonB function and stability. J. Bacteriol. 177:4742-4747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradbeer, C. 1993. The proton motive force drives the outer membrane transport of cobalamin in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 175:3146-3150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braun, V. 1995. Energy-coupled transport and signal transduction through the gram-negative outer membrane via TonB-ExbB-ExbD-dependent receptor proteins. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 16:295-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braun, V., and C. Herrmann. 1993. Evolutionary relationship of uptake systems for biopolymers in Escherichia coli: cross-complementation between the TonB-ExbB-ExbD and the TolA-TolQ-TolR proteins. Mol. Microbiol. 8:261-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braun, V., R. E. W. Hancock, K. Hantke, and A. Hartmann. 1976. Functional organization of the outer membrane of Escherichia coli: phage and colicin receptors as components of iron uptake systems. J. Supramol. Struct. 5:37-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braun, V., S. Gaisser, C. Herrmann, K. Kampfenkel, H. Killmann, and I. Traub. 1996. Energy-coupled transport across the outer membrane of Escherichia coli: ExbB binds ExbD and TonB in vitro, and leucine 132 in the periplasmic region and aspartate 25 in the transmembrane region are important for ExbD activity. J. Bacteriol. 178:2836-2845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cadieux, N., and R. J. Kadner. 1999. Site-directed disulfide bonding reveals an interaction site between energy-coupling protein TonB and BtuB, the outer membrane cobalamin transporter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:10673-10678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cadieux, N., C. Bradbeer, and R. J. Kadner. 2000. Sequence changes in the ton box region of BtuB affect its transport activities and interaction with TonB protein. J. Bacteriol. 182:5954-5961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang, C., A. Mooser, A. Plückthun, and A. Wlodawer. 2001. Crystal structure of the dimeric domain of TonB reveals a novel fold. J. Biol. Chem. 276:27535-27540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DiRita, V., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1991. Periplasmic interaction between two membrane regulatory proteins, ToxR and ToxS, results in signal transduction and transcriptional activation. Cell 64:29-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fischer, E., K. Günter, and V. Braun. 1989. Involvement of ExbB and TonB in transport across the outer membrane of Escherichia coli: phenotypic complementation of exb mutants by overexpressed tonB and physical stabilization of TonB by ExbB. J. Bacteriol. 171:5127-5134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fromant, M., S. Blanquet, and P. Plateau. 1995. Direct random mutagenesis of gene-sized DNA fragments using polymerase chain reaction. Anal. Biochem. 224:347-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaisser, S., and V. Braun. 1991. The tonB gene of Serratia marcescens: sequence, activity and partial complementation of Escherichia coli tonB mutants. Mol. Microbiol. 5:2777-2787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giacomini, A., B. Corich, F. J. Ollero, A. Squartini, and M. P. Nuti. 1992. Experimental conditions may affect reproducibiliby of the β-galactosidase assay. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 100:87-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Günter, K., and V. Braun. 1990. In vivo evidence for FhuA outer membrane interaction with the TonB inner membrane protein of Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 274:85-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanahan, D. 1983. Studies in transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J. Mol. Biol. 166:557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Härle, C., J. Kim, A. Angerer, and V. Braun. 1995. Signal transfer through three compartments: transcription initiation of the Escherichia coli ferric dicitrate transport system from the cell surface. EMBO J. 14:1430-1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heinrichs, D. E., and K. Poole. 1993. Cloning and sequence analysis of a gene (pchR) encoding an AraC family activator of pyochelin and ferripyochelin receptor synthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 175:5882-5889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higgs, P. I., P. S. Myers, and K. Postle. 1998. Interactions in the TonB-dependent energy transduction complex: ExbB and ExbD form homomultimers. J. Bacteriol. 180:6031-6038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgs, P. I., R. A. Larsen, and K. Postle. 2002. Quantification of known components of the Escherichia coli TonB energy transduction system: TonB, ExbB, ExbD and FepA. Mol. Microbiol. 44:271-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Howard, S. P., C. Herrmann, C. W. Stratilo, and V. Braun. 2001. In vivo synthesis of the periplasmic domain of TonB inhibits transport through the FecA and FhuA iron siderophore transporters of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183:5885-5895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kadner, R. J. 1990. Vitamin B12 transport in Escherichia coli: energy coupling between membranes. Mol. Microbiol. 4:2027-2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kampfenkel, K., and V. Braun. 1992. Membrane topology of the Escherichia coli ExbD protein. J. Bacteriol. 174:5485-5487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kampfenkel, K., and V. Braun. 1993. Membrane topologies of the TolQ and TolR proteins of Escherichia coli: inactivation of TolQ by a missense mutation in proposed first transmembrane segment. J. Bacteriol. 175:4485-4491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Killmann, H., and V. Braun. 1994. Energy-dependent receptor activities of Escherichia coli K-12: mutated TonB proteins alter FhuA receptor activities to phages T5, T1, phi 80 and to colicin M. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 119:71-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim, I., A. Stiefel, S. Plantör, A. Angerer, and V. Braun. 1997. Transcription induction of the ferric dicitrate transport genes via the N terminus of the FecA outer membrane protein, the Ton system and the electrochemical potential of the cytoplasmic membrane. Mol. Microbiol. 23:333-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kolmar, H., F. Hennecke, K. Gotze, B. Janzer, B. Vogt, F. Mayer, and H. J. Fritz. 1995. Membrane insertion of the bacterial signal transduction protein ToxR and requirements of transcription activation studied by modular replacement of different protein substructures. EMBO J. 14:3895-3904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larsen, R. A., and K. Postle. 2001. Conserved residues Ser(16) and His(20) and their relative positioning are essential for TonB activity, cross-linking of TonB with ExbB, and the ability of TonB to respond to proton motive force. J. Biol. Chem. 276:8111-8117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Larsen, R. A., D. Foster-Hartnett, M. A. McIntosh, and K. Postle. 1997. Regions of Escherichia coli TonB and FepA proteins essential for in vivo physical interactions. J. Bacteriol. 179:3213-3221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Larsen, R. A., M. G. Thomas, and K. Postle. 1999. Protonmotive force, ExbB and ligand-bound FepA drive conformational changes in TonB. Mol. Microbiol. 31:1809-1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lubkowski, J., F. Hennecke, A. Plückthun, and A. Wlodawer. 1999. Filamentous phage infection: crystal structure of g3p in complex with its coreceptor, the C-terminal domain of TolA. Structure Fold Des. 7:711-722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 33.Miller, V. L., R. K. Taylor, and J. J. Mekalanos. 1987. Cholera toxin transcriptional activator ToxR is a transmembrane DNA binding protein. Cell 48:271-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moeck, G. S., and L. Letellier. 2001. Characterization of in vitro interactions between a truncated TonB protein from Escherichia coli and the outer membrane receptors FhuA and FepA. J. Bacteriol. 183:2755-2764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moeck, G. S., J. W. Coulton, and K. Postle. 1997. Cell envelope signalling in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 272:28391-28397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ogierman, M., and V. Braun. 2003. Interactions between the outer membrane ferric citrate transporter FecA and TonB: studies of the FecA TonB box. J. Bacteriol. 185:1870-1885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Postle, K.,. 1993. TonB protein and energy transduction between membranes. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 25:591-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 39.Schlesinger, M. J. 1967. Formation of a defective alkaline phosphatase subunit by a mutant of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 242:1604-1611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schöffler, H., and V. Braun. 1989. Transport across the outer membrane of Escherichia coli K-12 via the FhuA receptor is regulated by the TonB protein of the cytoplasmic membrane. Mol. Gen. Genet. 217:378-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Skare, J. T., B. M. Ahmer, C. L. Seachord, R. P. Darveau, and K. Postle. 1993. Energy transduction between membranes. TonB, a cytoplasmic membrane protein, can be chemically cross-linked in vivo to the outer membrane receptor FepA. J. Biol. Chem. 268:16302-16308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takeshita, S., M. Sato, M. Toba, W. Masahashi, and T. Hashimoto-Gotoh. 1987. High-copy-number and low-copy-number plasmid vectors for lacZ α-complementation and chloramphenicol- or kanamycin-resistance selection. Gene 61:63-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Traub, I., and V. Braun. 1994. Energy-coupled colicin transport through the outer membrane of Escherichia coli K-12: mutated TonB proteins alter receptor activities and colicin uptake. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 119:65-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Traub, I., S. Gaisser, and V. Braun. 1993. Activity domains of the TonB protein. Mol. Microbiol. 8:409-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Van Hove, B., H. Staudenmaier, and V. Braun. 1990. Novel two-component transmembrane transcription control: regulation of iron dicitrate transport in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 172:6749-6758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang, R. F., and S. R. Kushner. 1991. Construction of versatile low-copy-number vectors for cloning, sequencing and gene expression in Escherichia coli. Gene 100:195-199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Witty, M., C. Sanz, A. Shah, J. G. Grossmann, K. Mizuguchi, R. N. Perham, and B. Luisi. 2002. Structure of the periplasmic domain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa TolA: evidence for an evolutionary relationship with the TonB transporter protein. EMBO J. 21:4207-4218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]