Abstract

The relA gene of Escherichia coli encodes guanosine 3′,5′-bispyrophosphate (ppGpp) synthetase I, a ribosome-associated enzyme that is activated during amino acid starvation. The stringent response is thought to be mediated by ppGpp. Mutations in relA are known to result in pleiotropic phenotypes. We now report that three different relA mutant alleles, relA1, relA2, and relA251::kan, conferred temperature-sensitive phenotypes, as demonstrated by reduced plating efficiencies on nutrient agar (Difco) or on Davis minimal agar (Difco) at temperatures above 41°C. The relA-mediated temperature sensitivity was osmoremedial and could be completely suppressed, for example, by the addition of NaCl to the medium at a concentration of 0.3 M. The temperature sensitivities of the relA mutants were associated with decreased thermotolerance; e.g., relA mutants lost viability at 42°C, a temperature that is normally nonlethal. The spoT gene encodes a bifunctional enzyme possessing ppGpp synthetase and ppGpp pyrophosphohydrolase activities. The introduction of the spoT207::cat allele into a strain bearing the relA251::kan mutation completely abolished ppGpp synthesis. This ppGpp null mutant was even more temperature sensitive than the strain carrying the relA251::kan mutation alone. The relA-mediated thermosensitivity was suppressed by certain mutant alleles of rpoB (encoding the β subunit of RNA polymerase) and spoT that have been previously reported to suppress other phenotypic characteristics conferred by relA mutations. Collectively, these results suggest that ppGpp may be required in some way for the expression of genes involved in thermotolerance.

Amino acid deprivation results in the global readjustment of metabolic activities in Escherichia coli. This phenomenon, designated the stringent response, may be designed to promote bacterial survival during periods of starvation (for a review, see reference 1). The hallmark of the stringent response is rapid intracellular accumulation of guanosine 3′,5′-bispyrophosphate (ppGpp). Amino acid starvation activates ppGpp synthetase I, a ribosome-associated enzyme encoded by the relA gene that catalyzes the synthesis of ppGpp. The metabolic changes associated with the stringent response are thought to be mediated by ppGpp. Thus, the so-called relaxed (relA) mutants of E. coli are unable to accumulate ppGpp in response to amino acid deprivation and consequently do not exhibit the stringent response. Alternatively, the stringent response is phenotypically blocked by agents, such as chloramphenicol, that inhibit the activation of RelA. A wide range of metabolic activities is regulated by ppGpp, either positively or negatively, but much remains to be learned about the underlying mechanisms.

The accumulation of ppGpp also occurs in a RelA-independent fashion, for example, during carbon source downshift (1). This reaction is catalyzed by ppGpp synthetase II, the product of the spoT gene (8, 30). SpoT also exhibits a 3′-pyrophosphatase activity that is the primary mechanism for ppGpp degradation during recovery from starvation (22).

Mutations affecting ppGpp metabolism result in pleiotropic phenotypes, suggesting that this nucleotide plays a complex role in cellular physiology (1). One relevant example is the so-called (p)ppGpp0 mutants that carry deletions in both relA and spoT (30). These (p)ppGpp-deficient mutants have nearly normal growth rates on complex media but exhibit a multiple amino acid auxotrophic phenotype on minimal medium. We report here a new phenotype associated with relA mutations. We demonstrate that relA mutants exhibit temperature-sensitive growth. This temperature sensitivity was correlated to significantly decreased levels of thermotolerance. The temperature sensitivity was suppressed by certain mutant alleles of rpoB, the gene encoding the β subunit of RNA polymerase, by mutations in spoT that result in increased basal ppGpp levels, and by high osmolarity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

All of the bacteria used in this study were derivatives of E. coli K-12. A list of the strains and recombinant plasmids used in this study is shown in Table 1. Plasmids were electroporated into bacteria with a Bio-Rad Gene Pulser. Bacterial strains were constructed for this study by P1vir-mediated transduction as described by Miller (16).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype or description | Source (reference) |

|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | ||

| CF1693 | ΔrelA251::kan ΔspoT207::cat | M. Cashel |

| CF1736 | pyrE+spoT202 | M. Cashel |

| CF1738 | pyrE+spoT203 | M. Cashel |

| CF1740 | pyrE+spoT204 | M. Cashel |

| CF1964 | btuB::Tn10 rpoB7 | M. Cashel |

| CF1969 | btuB::Tn10 rpoB3443 | M. Cashel |

| CF1970 | btuB::Tn10 rpoB3449 | M. Cashel |

| CF1971 | btuB::Tn10 rpoB114 | M. Cashel |

| CF1972 | btuB::Tn10 rpoB337 | M. Cashel |

| CF4268 | btuB::Tn10 rpoB3445 | M. Cashel |

| CF4297 | btuB::Tn10 rpoB3401 | M. Cashel |

| CF5034 | pyrE60 zib-563::Tn10 | M. Cashel |

| CP79 | relA2 | Laboratory collection |

| MC4100 | relA1 | Laboratory collection |

| VC348 | zei-348::Tn5 | Laboratory collection |

| VC6129 | W3110 ΔrelA251::kan (W3110 × CF1693) | This study |

| VC6130 | VC6129 ΔspoT207::cat (VC6129 × CF1693) | This study |

| VC6132 | W3110 zei-348::Tn5 relA+ | This study |

| VC6133 | W3110 zei-348::Tn5 relA2 | This study |

| VC6141 | W3110 zei-348::Tn5 relA1 | This study |

| VC6159 | VC6129 btuB::Tn10 rpoB+ (VC6129 × CF1970) | This study |

| VC6158 | VC6129 btuB::Tn10 rpoB3449 (VC6129 × CF1970) | This study |

| VC6160 | VC6129 btuB::Tn10 rpoB3401 (VC6129 × CF4297) | This study |

| VC6166 | VC6129 btuB::Tn10 rpoB3445 (VC6129 × CF4268) | This study |

| VC6173 | VC6129 btuB::Tn10 rpoB7 (VC6129 × CF1964) | This study |

| VC6191 | VC6129 btuB::Tn10 rpoB114 (VC6129 × CF1971) | This study |

| VC6192 | VC6129 btuB::Tn10 rpoB3443 (VC6129 × CF1969) | This study |

| VC6193 | VC6129 btuB::Tn10 rpoB3370 (VC6129 × CF1972) | This study |

| VC7237 | VC6141 zib-563::Tn10 | This study |

| VC7238 | VC6141 pyrE60 zib-563::Tn10 (VC6141 × CF5034) | This study |

| VC7239 | VC6141 spoT202 (VC6141 × CF1736) | This study |

| VC7240 | VC6141 spoT203 (VC6141 × CF1738) | This study |

| VC7241 | VC6141 spoT204 (VC6141 × CF1740) | This study |

| W3110 | Prototrophic | Laboratory collection |

| Plasmids | ||

| pALS10 | Apr; E. coli relA clone | J. Zyskind (23) |

| pALS13 | Apr; truncated E. coli relA clone | J. Zyskind (23) |

| pDJJ12 | Apr; ColE1 derivative carrying E. coli rpoBC | M. Cashel (11) |

| pDS1 | Cmr; E. coli rpoH in pACYC184 | C. A. Gross |

Strains carrying the relA251::kan and spoT207::cat alleles were constructed by direct selection of kanamycin-resistant and chloramphenicol-resistant transductants, respectively. Strains carrying the relA1 and relA2 alleles were constructed by using the closely linked zei-348::Tn5 insertion as a selective marker. In these constructions, the relA genotypes of the kanamycin-resistant transductants were determined by screening for sensitivity to a combination of serine, methionine, and glycine (25) and for sensitivity to 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole (20). The relA genotypes of the transductants were confirmed by measuring the incorporation of [5,6-3H]uracil (Amersham) into stable RNA in amino acid-deprived cultures as described previously (10). Two strains carrying each of the three relA alleles that were independently constructed were tested for temperature sensitivity in preliminary experiments. The duplicate strains exhibited identical temperature- sensitive phenotypes, and one representative from each set, strains VC6129 (relA251::kan), VC6133 (relA2), and VC6141 (relA1), was used in the experiments described here.

It should be noted that Pao and Gallant (18) have characterized a mutation in a gene they designated relX that decreased intracellular levels of ppGpp and caused temperature-sensitive growth. We deliberately chose the zei-348::Tn5 marker for the construction of relA mutants to minimize the possibility of picking up relX mutations from our donor strains. The zei-348::Tn5 marker is closely linked to cysC and is therefore more closely linked to relA than to relX. In retrospect, we were unable to demonstrate relX in our strains (unpublished data).

Derivatives of VC6129 carrying the various rpoB alleles were constructed by using the linked btuB::Tn10 insertion as a selective marker. All of the mutant rpoB alleles conferred resistance to rifampin, and this property was used to identify the rpoB transductants.

Derivatives of strain VC6141 carrying spoT202, spoT203, and spoT204 were constructed essentially as described by Sarubbi et al. (21). Briefly, the procedure was as follows. In the first step, the linked markers pyrE60 and zib-563::Tn10 were cotransduced from CF5034 into VC6141 by selection for tetracycline resistance to create strain VC7238. Strain VC7237 was a tetracycline-resistant transductant that did not coinherit pyrE60. In the second step, the various spoT alleles from pyrE+ donors were transduced into VC7238 and pyrE+ transductants were selected for. The spoT derivatives were obtained by screening the pyrE+ transductants that formed small colonies in the presence of tetracycline (M. Cashel, personal communication).

Media and growth conditions.

Bacteria were routinely grown in nutrient broth or nutrient agar (Difco) unless indicated otherwise. Other media used during the course of this study were M9 minimal medium (16), Davis minimal medium (Difco), Luria broth or agar as described by Miller (Difco), tryptic soy agar (Difco), LB broth or agar as described by Lennox (Difco), and LB broth or agar as described by Miller (Difco). Broth cultures were grown in Gyrotory water bath shakers (New Brunswick Scientific Co.), and culture turbidity was measured with a Beckman DU-64 spectrophotometer at 600 nm. The effect of the incubation temperature on colony formation is expressed as plating efficiency, which, in most experiments, is defined as the ratio of colony formation at 42°C to colony formation at 30°C, as determined in the following way. Bacteria were serially diluted in sterile saline (0.015 M NaCl). For each dilution, aliquots of 100 μl were plated in quadruplicate on nutrient agar, and two plates for each dilution were incubated at 30°C and at 42°C for 36 h before counting. In Fig. 1, a full range of temperatures was used, and in this case, the plating efficiencies are defined as the ratio of the colony count at the higher temperature to the colony count at 30°C. The experiments described in this report were performed with exponential-phase as well as stationary-phase bacteria. It is noteworthy that the same results were obtained in all cases, and the growth phase apparently did not influence the temperature sensitivity of the relA mutants. Unless indicated otherwise, the data shown were obtained with bacterial cultures that were 1 to 2 h into stationary phase.

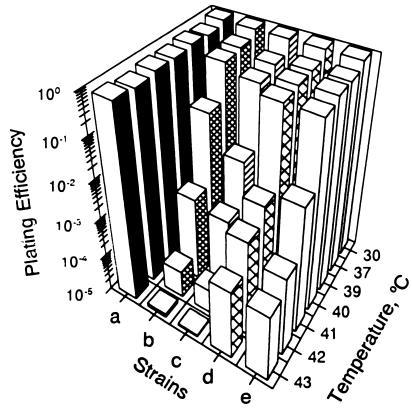

FIG. 1.

Temperature-sensitive growth of relA mutants. A set of isogenic strains carrying three common relA mutant alleles were constructed. These strains were compared for growth on nutrient agar at temperatures ranging from 30 to 43°C. Growth is expressed as plating efficiency (plate counts at the high temperature divided by plate counts at 30°C). a, strain VC6132 (wild type); b, strain VC6129 (ΔrelA251::kan); c, strain VC6130 (ΔrelA251::kan ΔspoT207::cat); d, strain VC6133 (relA2); e, strain VC6141 (relA1).

Bacterial survival at 55°C.

Bacteria were grown in nutrient broth at 30°C and harvested by centrifugation either during exponential phase (optical density of 0.5) or after 1 h in stationary phase. The cells were resuspended in sterile saline to a density of approximately 2 × 109/ml. A 1-ml suspension was incubated in a water bath set at 55°C. Samples (50 μl) were removed at the indicated times, diluted, and plated on nutrient agar. The survivors of the heat treatment were determined from the plate counts after 36 h of incubation at 30°C.

RESULTS

Temperature-sensitive growth of relA mutants.

This investigation was initiated when it was fortuitously observed that several key E. coli strains carrying mutations in relA exhibited temperature-sensitive growth on certain media. For example, strains CF1693 (ΔrelA251::kan ΔspoT207::cat), CP79 (relA2), and MC4100 (relA1) all failed to produce colonies on nutrient agar at 42°C. A more extensive survey of our culture collection revealed that temperature-sensitive growth is a common phenotype associated with all of the relA mutants tested. To establish the relationship between mutations in relA and temperature sensitivity, a set of isogenic derivatives of strain W3110 carrying the relA1, relA2, and ΔrelA251::kan alleles were constructed by phage P1-mediated transduction (Table 1). Figure 1 compares the plating efficiencies of these strains with the plating efficiency of an isogenic relA+ strain, VC6132, on nutrient agar as a function of incubation temperature. All of the relA mutants had nearly normal plating efficiencies at temperatures as high as 39 to 40°C, but they progressively lost colony-forming capabilities at higher temperatures. Temperature sensitivity was especially notable in strain VC6129 (ΔrelA251::kan) and in a derivative of VC6129, strain VC6130, carrying the ΔspoT207::cat allele (Fig. 1, strains b and c, respectively). Both strains exhibited temperature-sensitive growth at 40°C and higher temperatures. In comparison, strains VC6133 and VC6141, which carry the relA1 and relA2 alleles, respectively, showed normal colony formation at 40°C but were sensitive to higher temperatures (Fig. 1, strains d and e, respectively). Additional comparative studies indicated that the plating efficiencies of strains carrying the relA1 and relA2 alleles, such as VC61333 and VC6141 (Fig. 1, strains d and e, respectively), were consistently more than 10-fold higher than those of strains carrying the ΔrelA251::kan allele. Although the plating efficiencies of strains VC6129 and VC6130 were roughly similar in these experiments, data presented below indicate that VC6130 was less thermotolerant than VC6129. This suggests that the ΔspoT207::cat allele exacerbated the temperature-sensitive phenotype associated with ΔrelA251::kan.

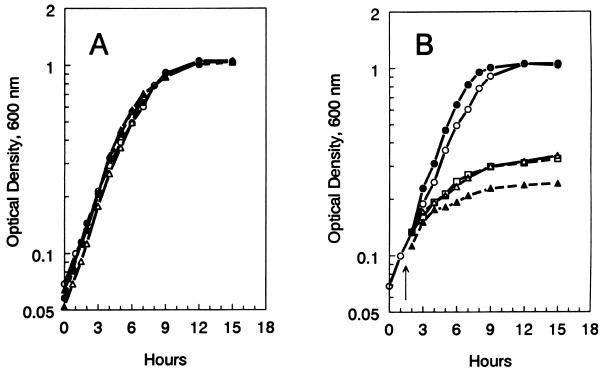

Temperature sensitivity was also demonstrated in nutrient broth. As shown in Fig. 2A, all of the strains grew at 30°C, with doubling times ranging from 110 to 114 min. On the other hand, only the wild-type strain, VC6132, grew at 42°C (Fig. 2B). Cultures of the relA mutants, VC6129, VC6133, and VC6141, stopped growing after less than two doublings at the restrictive temperature.

FIG. 2.

Growth in nutrient broth at 30°C (A) and at 42°C (B). Symbols: •, strain VC6132 (wild type); ▵, strain VC6129 (ΔrelA251::kan); ▴, strain VC6133 (relA2); □, strain VC6141 (relA1). In panel B, cultures growing at 30°C were shifted to 42°C at 1.5 h (arrow). For comparison, the growth of a culture of strain VC6132 (wild type) at 30°C (○) is also shown.

The temperature sensitivity phenotypes of strains VC6129, VC6133, and VC6141 on nutrient agar or in nutrient broth were eliminated by the introduction of plasmid pALS10 (relA+) but not by the introduction of plasmid pALS14 (truncated inactive relA). These results indicate that the temperature-sensitive growth of these strains was directly attributable to the mutations in relA.

Osmoremediation of relA-mediated temperature-sensitive growth.

As noted above, the relA-associated temperature sensitivity was dependent on the growth medium. We have routinely used nutrient agar or broth for most of our experiments. However, the temperature-sensitive phenotype of relA mutants could also be demonstrated on minimal media such as M9 and Davis minimal media (supplemented with a mixture of amino acids in the case of strain VC6130). All relA mutant strains were heat resistant on most common complex media, such as tryptic soy medium. Moreover, it is noteworthy that Luria broth or agar and the various formulations of Luria-Bertani medium supported colony formation of relA mutants at 42°C.

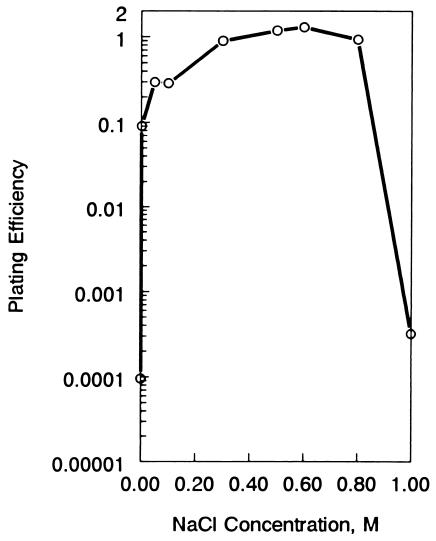

The observed medium dependence probably reflected the osmolarity of the growth medium because the relA-associated temperature-sensitive phenotype was osmoremedial. The ability of relA mutants to form colonies on nutrient agar or on Davis minimal agar at temperatures as high as 43°C was restored by the addition of NaCl (0.3 M), KCl (0.1 M), or sucrose (0.35 M) to the medium. Figure 3 shows the effects of adding different concentrations of NaCl to nutrient agar on the plating efficiency of strain VC6129. A final concentration of 0.3 to 0.8 M NaCl completely abolished temperature sensitivity at 42°C. A similar experiment with KCl showed that it was an effective suppressor of temperature sensitivity at 0.1 to 0.3 M (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Effect of medium osmolarity on colony formation by strain VC6129 (ΔrelA251::kan). Nutrient agar plates containing the indicated amounts of NaCl were inoculated with a series of dilutions of an exponential-phase culture of strain VC6129. Duplicate sets of plates were prepared for each salt concentration, with one set incubated at 30°C and the other incubated at 42°C. Colonies were counted after 36 h of incubation, and plating efficiencies (colony count at 42°C divided by colony count at 30°C) were calculated for each salt concentration.

Suppression of relA-mediated temperature-sensitive growth by mutations in rpoB.

As noted above, (p)ppGpp0 strains, such as VC6130 (ΔrelA251::kan ΔspoT207::cat), possess pleiotropic phenotypes. For example, they are multiauxotrophic on minimal medium (30). This multiauxotrophic phenotype is suppressed by certain mutant alleles of rpoB (1). A representative collection of rpoB alleles were transduced into VC6129 to determine whether they also suppress the relA-associated temperature sensitivity. As shown in Table 2, four of the seven rpoB alleles tested restored heat resistance. Identical results were obtained with derivatives of VC6130 carrying these rpoB alleles (data not shown). Interestingly, these same four alleles were the only ones in the collection capable of suppressing the (p)ppGpp0-associated multiauxotrophic phenotype (M. Cashel, personal communication), suggesting that this phenomenon is mechanistically related to relA-associated temperature sensitivity.

TABLE 2.

Suppression of thermosensitive phenotype of strain VC6129 (ΔrelA251::kan) mutants by mutations in rpoB gene

| Strain | Allele | Mutation in RpoB | Plating efficiencya |

|---|---|---|---|

| VC6159 | rpoB+ | None | 4.4 × 10−5 |

| VC6158 | rpoB3449 | Δ532A | 0.91 |

| VC6160 | rpoB3401 | R529C | 6.2 × 10−5 |

| VC6166 | rpoB3445 | Δ(507-511)V | 3.7 × 10−5 |

| VC7262 | rpoB8 | Q513P | 2.4 × 10−5 |

| VC6191 | rpoB114 | S531F | 0.94 |

| VC6192 | rpoB3443 | L533P | 0.92 |

| VC6193 | rpoB3370 | T563P | 0.82 |

Ratio of colony formation at 42°C to colony formation at 30°C.

Suppression of the temperature-sensitive phenotype of VC6141 by spoT mutant alleles.

Sarubbi et al. (21) have described spoT mutant alleles that raise the basal levels of ppGpp in relA1 backgrounds. Derivatives of strain VC6141 (relA1) carrying three such spoT alleles were constructed. Table 3 shows that these spoT alleles significantly restored colony formation in the relA1 mutant at 42°C. These results suggest that the temperature sensitivity exhibited by the relA mutants is directly related to decreased basal levels of (p)ppGpp.

TABLE 3.

Suppression of relA1-mediated temperature sensitivity by spoT mutant alleles

| Strain | Relevant genotype | Plating efficiencya |

|---|---|---|

| VC7237 | relA1 spoT+ | 2.3 × 10−3 |

| VC7239 | relA1 spoT202 | 0.12 |

| VC7240 | relA1 spoT203 | 0.34 |

| VC7241 | relA1 spoT204 | 0.46 |

Ratio of colony formation at 42°C to colony formation at 30°C.

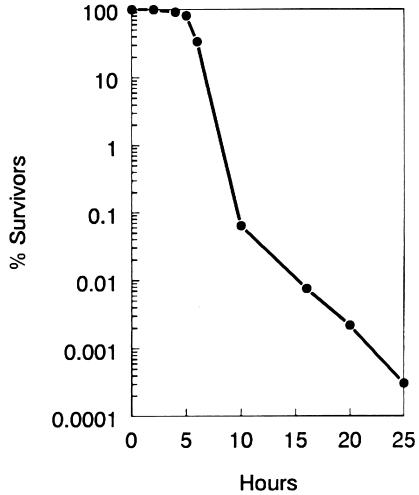

Decreased thermotolerance of relA mutants.

Figure 4 shows that incubation at 42°C was lethal to relA mutants, e.g., strain VC6129. Identical sets of plates inoculated with a serial dilution of VC6129 were incubated at 42°C beginning at 0 h. At the indicated times, sets of plates were removed and incubated further at 30°C to determine the number of bacteria that had survived the period of incubation at 42°C. In the case of VC6129, less than 50% of the original cells were able to form colonies at 30°C after a 7-h period of incubation at 42°C. Moreover, there was less than 0.1% survival after 10 h.

FIG. 4.

Killing of strain VC6129 (ΔrelA251::kan) at 42°C. Identical sets of plates inoculated with serial dilutions of strain VC6129 were incubated at 42°C beginning at 0 h. At the indicated times, sets of plates were removed and incubated further at 30°C to determine the number of survivors of the 42°C treatment.

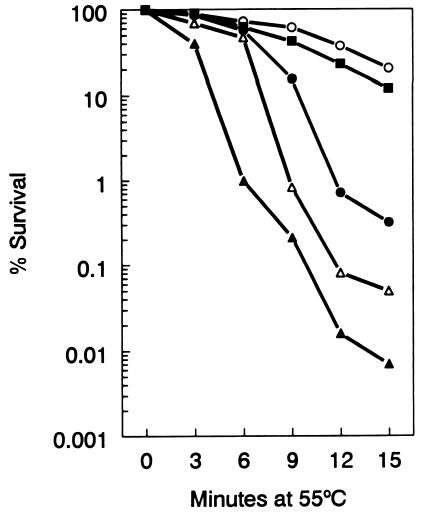

A set of strains carrying the ΔrelA251::kan allele were compared for survival at 55°C. Figure 5 shows that relA251::kan mutant strain VC6129 was significantly less thermotolerant than relA+ strain VC6132. Thermotolerance was restored to nearly wild-type levels by the introduction of plasmid pALS10 (relA+) into strain VC6129. Moreover, strain VC6130 was killed at a faster rate at 55°C than strain VC6129, indicating that the presence of the spoT207::cat mutation further reduced the thermotolerance associated with the relA251::kan allele. Derivatives of strain VC6129 carrying rpoB suppressor mutations, e.g., strain VC6158 with rpoB3449, were significantly more thermoresistant, although their levels of thermoresistance were still not restored to the wild-type level. Collectively, the results described here suggest that the relA-associated temperature-sensitive growth phenotype was associated with decreased thermotolerance. The results shown in Fig. 5 were obtained with exponential-phase cells. Virtually identical results were obtained when stationary-phase bacteria were used. Moreover, the thermotolerance of strain VC6129 (ΔrelA251::kan) was not improved by cell growth at 37°C or by a brief (30-min) preexposure of the cells to 42°C prior to testing (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Decreased thermotolerance conferred by relA mutation. Suspensions of bacteria in saline were incubated at 55°C. At the indicated times, samples were removed and the numbers of survivors were determined. Symbols: ○, strain VC6132 (wild type); ▵, strain VC6129 (ΔrelA251::kan); ▪, strain VC6129 carrying plasmid pALS10 (relA+); ▴, strain VC6130 (ΔrelA251::kan ΔspoT207::cat); •, strain VC6158 (ΔrelA251::kan rpoB3449).

DISCUSSION

Here we show that all three commonly used relA mutant alleles conferred temperature-sensitive growth phenotypes. In each case, temperature sensitivity was eliminated by the introduction of a recombinant plasmid carrying the wild-type relA gene but not by one carrying a truncated relA gene. Furthermore, the spoT mutant alleles described by Sarubbi et al. (21) that cause increased basal levels of ppGpp in a relA1 background partially suppressed the temperature-sensitive phenotype of the relA1 mutant strain. It was also noted that the ΔrelA251::kan strain was significantly more temperature sensitive than strains carrying the relA1 and relA2 alleles, and this may reflect the leakiness of the latter mutant alleles. Furthermore, the temperature sensitivity of the ΔrelA251::kan strain was exacerbated by the introduction of the ΔspoT207::cat mutation. Collectively, these results indicate that the observed temperature sensitivity was directly attributable to decreased intracellular levels of (p)ppGpp.

The temperature-sensitive phenotypes of the relA mutant strains were osmoremedial and were only evident in media of low osmotic strength. The osmolarities of most common media, e.g., the various formulations of LB, were adequate to support growth at high temperature. The relA-mediated temperature sensitivity was suppressed by increasing the osmolarity of nonpermissive growth media with a variety of solutes, e.g., NaCl, KCl, or sucrose. Osmoremedial temperature-sensitive mutations are apparently quite common, but how the increase in external osmolarity suppresses the mutant phenotypes is far from understood (3). In some instances, it has been proposed that the resulting increase in the intracellular concentration of a compatible solute could lead to the stabilization of a temperature-sensitive mutant protein (3). This is an unlikely explanation for the relA-mediated temperature sensitivity. For example, strains carrying the ΔrelA251::kan mutation did not produce RelA but still exhibited an osmoremedial temperature-sensitive phenotype. Therefore, as an alternative, we are investigating the possibility that the osmoremedial characteristic may instead be related to some aspect of osmoregulated gene expression.

The relA-mediated temperature sensitivity was suppressed by four of the seven rpoB mutant alleles tested. The alleles used in this study have been systematically characterized and shown to possess altered transcriptional termination activities (11, 12). The connection between mutations in rpoB and ppGpp-dependent phenomena is well documented. The four rpoB alleles that suppress relA-mediated temperature sensitivity were previously shown to suppress the multiauxotrophic phenotypes of ppGpp-deficient mutants (1; M. Cashel, personal communication). These same alleles also enhanced the survival of ppGpp-deficient strains during prolonged stationary phase (1). Mutations in rpoB have also been reported to suppress the sensitivity of relA mutants to serine, methionine, and glycine (25, 26) and have been shown relieve the growth-inhibitory effects of high levels of ppGpp (24). The multiauxotrophic phenotype of ppGpp-deficient mutants is corrected not only by the aforementioned rpoB alleles but also by certain mutations in rpoC and rpoD, the genes encoding the β′ and σ70 subunits of RNA polymerase, respectively (1, 9). It is intriguing that seemingly distinct phenomena, e.g., multiauxotrophy and temperature sensitivity, are suppressed by common mechanisms, i.e., mutations in RNA polymerase. These findings suggest that these ppGpp-dependent phenomena may have a transcriptional basis, and it would be interesting to consider the possibility that they have the same underlying basis.

Evidence for the direct and specific binding of ppGpp to the β subunit of RNA polymerase has been presented (2, 19). The in vitro activities of RNA polymerase, to which azido-ppGpp had been cross-linked, were compared on stringent and nonstringent promoters (2). The transcription of ribosomal genes was inhibited by azido-ppGpp, whereas transcription from the lacUV5 promoter was unaffected. It will therefore be of interest to determine whether there is a relationship between these findings and ppGpp-dependent phenomena such as multiauxotrophy and thermotolerance.

We have considered the possibility that ppGpp is required for the expression of genes that are necessary for thermotolerance, and an obvious possibility was the involvement of those encoding heat shock proteins. The heat shock response is dependent on the concentration of σ32, and heat shock protein synthesis can even be induced in the absence of heat shock when σ32 is overproduced (5). We have shown that the overproduction of σ32 from plasmid pDS1 did not relieve the relA-mediated temperature sensitivity (data not shown). However, in retrospect, this is perhaps not surprising since VanBogelen et al. (27) have shown that induction of the heat shock regulon by induction of σ32 overproduction at 28°C is, for unknown reasons, insufficient to confer thermotolerance. More importantly, we did not detect any differences in gene expression patterns by DNA microarray technology in relA+ and relA mutant bacteria during heat shock induction, suggesting that the heat shock response is functional in relA mutant strains (X. Yang and E. E. Ishiguro, unpublished data). This confirms the unpublished data of A. D. Grossman (cited in reference 6). Moreover, VanBogelen and Neidhardt (29) have demonstrated that strain CF1946, a W3110 derivative carrying ΔrelA251::kan ΔspoT207::cat, exhibited a heat shock response, albeit an altered one. They observed that strain CF1946 normally had a higher basal level of several heat shock proteins when it was grown at 30°C. The heat shock regulon was induced when CF1946 was subjected to a temperature upshift to 42°C, but this induction occurred 10 min later than that observed in wild-type strain W3110. It is interesting that VanBogelen and Neidhardt (29) also observed in this experiment that CF1946 was temperature sensitive and failed to grow at 42°C, but no attempt was made to correlate the temperature sensitivity to the ΔrelA251::kan and ΔspoT207::cat mutations. It has been previously noted that temperature upshifts result in the accumulation of ppGpp (18, 28), but VanBogelen and Neidhardt (29) concluded from their results that ppGpp was neither sufficient nor necessary for induction of the heat shock regulon. In an earlier study, Grossman et al. (6) demonstrated that the expression of heat shock proteins was induced during the stringent response. In their experiments, a temperature-sensitive valyl-tRNA synthetase mutant was shifted from 28 to 33.5°C, a semipermissive temperature at which protein synthesis was inhibited by about 50% with the concomitant increase in ppGpp levels. The induction of heat shock protein synthesis under these conditions was relA+ dependent and did not occur in an isogenic relA mutant strain. Curiously, heat shock protein synthesis during the stringent response also occurred in an rpoH mutant strain. In contrast, subsequent studies by VanBogelen et al. (28) indicated that the heat shock response was not induced when the stringent response was invoked by isoleucine deprivation. Therefore, it is not clear what role, if any, ppGpp plays in induction of the heat shock response. Nevertheless, we conclude from our studies that the expression of heat shock proteins is not sufficient to relieve the temperature sensitivity exhibited by relA mutant strains.

The rpoS gene encodes the σs transcription factor that is required for the expression of stationary phase-induced and osmoregulated genes in E. coli (7, 15). Gentry et al. (4) have shown that ppGpp is required for expression of the rpoS gene. Moreover, Kvint et al. (13, 14) have demonstrated that ppGpp is required for expression of RpoS-dependent genes in addition to σs. Because of the connection to ppGpp and, possibly, to osmoregulated gene expression, it was possible that the temperature sensitivity of the relA mutants could be attributable to their inability to express a key RpoS-dependent gene required for thermotolerance. However, strain UM122, which carries an insertion-inactivated rpoS gene (17), is not temperature sensitive (E. E. Ishiguro, unpublished data). Therefore, it seems unlikely that RpoS is involved in the relA-mediated temperature-sensitive phenotype.

In summary, the basis for relA-dependent thermotolerance appears to be complex. The suppression of temperature sensitivity in relA mutants by certain rpoB alleles suggests the involvement of an unknown aspect of gene expression. This characteristic is common to other relA-dependent phenotypes, and the relationship between relA and RNA polymerase must be elucidated in order to gain a better understanding of relA-dependent thermotolerance.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mike Cashel for strains and valuable dialogue.

This work was supported by a grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cashel, M., D. R. Gentry, V. J. Hernandez, and D. Vinella. 1996. The stringent response, p. 1458-1496. In F. C. Neidhardt, R. Curtiss III, J. L. Ingraham, E. C. C. Lin, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, W. S. Reznikoff, M. Riley, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 2.Chatterji, D., N. Fujita, and A. Ishihama. 1998. The mediator for stringent control, ppGpp, binds to the β-subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. Genes Cells 3:279-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Csonka, L. N. 1989. Osmoregulation in bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 53:121-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gentry, D. R., V. J. Hernandez, L. H. Nguyen, D. B. Jensen, and M. Cashel. 1993. Synthesis of the stationary-phase sigma factor σS is positively regulated by ppGpp. J. Bacteriol. 175:7982-7989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grossman, A. D., D. B. Straus, W. A. Walter, and C. A. Gross. 1987. Sigma 32 synthesis can regulate the synthesis of heat shock proteins in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 1:179-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grossman, A. D., W. E. Taylor, Z. F. Burton, R. R. Burgess, and C. A. Gross. 1985. Stringent response in Escherichia coli induces expression of heat shock proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 186:357-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hengge-Aronis, R. 1996. Back to log phase: sigma S as a global regulator in the osmotic control of gene expression in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 21:887-893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hernandez, V. J., and H. Bremer. 1991. Escherichia coli ppGpp synthetase II activity requires spoT. J. Biol. Chem. 266:5991-5999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hernandez, V. J., and M. Cashel. 1995. Changes in conserved region 3 of Escherichia coli sigma 70 mediate ppGpp-dependent functions in vivo. J. Mol. Biol. 252:536-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ishiguro, E. E., and W. D. Ramey. 1976. Stringent control of peptidoglycan biosynthesis in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 127:1119-1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jin, D. J., and C. A. Gross. 1988. Mapping and sequencing of mutations in the Escherichia coli rpoB gene that lead to rifampicin resistance. J. Mol. Biol. 202:45-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jin, D. J., W. A. Walter, and C. A., Gross. 1988. Characterization of the termination phenotypes of rifampicin-resistant mutants. J. Mol. Biol. 202:245-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kvint, K., A. Farewell, and T. Nystrom. 2000. RpoS-dependent promoters require guanosine tetraphosphate for induction even in the presence of high levels of σs. J. Biol. Chem. 275:14795-14798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kvint, K., C. Hosbond, A. Farewell, O. Nyebroe, and T. Nystrom. 2000. Emergency derepression: stringency allows RNA polymerase to override negative control by an active repressor. Mol. Microbiol. 35:435-443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loewen, P. C., B. Hu, J. Strutinsky, and R. Sparling. 1998. Regulation in the rpoS regulon of Escherichia coli. Can. J. Microbiol. 44:707-717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 17.Mulvey, M. R., P. A. Sorby, B. L. Triggs-Raine, and P. C. Loewen. 1988. Cloning and physical characterization of katE and katF required for catalase HPII expression in Escherichia coli. Gene 73:337-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pao, C. C., and J. Gallant. 1978. A gene involved in the metabolic control of ppGpp synthesis. Mol. Gen. Genet. 158:271-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reddy, P. S., A. Raghavan, and D. Chatterji. 1995. Evidence for a ppGpp-binding site on Escherichia coli RNA polymerase: proximity relationship with the rifampicin-binding domain. Mol. Microbiol. 15:255-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rudd, K. E., B. R. Bochner, M. Cashel, and J. R. Roth. 1985. Mutations in the spoT gene of Salmonella typhimurium: effects on his operon expression. J. Bacteriol. 163:534-542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sarubbi, E., K. E. Rudd, and M. Cashel. 1988. Basal ppGpp level adjustment shown by new spoT mutants affect steady state growth rates and rrnA ribosomal promoter regulation in Escherichia coli. Mol. Gen. Genet. 213:214-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sarubbi, E., K. E. Rudd, H. Xiao, K. Ikehara, M. Kalman, and M. Cashel. 1989. Characterization of the spoT gene of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 264:15074-15082. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Svitil, A. L., M. Cashel, and J. W. Zyskind. 1993. Guanosine tetraphosphate inhibits protein synthesis in vivo: a possible protective mechanism for starvation stress in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 268:2307-2311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tedin, K., and H. Bremer. 1992. Toxic effects of high levels of ppGpp in Escherichia coli are relieved by rpoB mutations. J. Biol. Chem. 267:2337-2344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uzan, M., and A. Danchin. 1976. A rapid test for the relA mutation in E. coli. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 69:751-758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uzan, M., and A. Danchin. 1978. Correlation between the serine sensitivity and the derepressibility of the ilv genes in Escherichia coli relA− mutants. Mol. Gen. Genet. 165:21-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.VanBogelen, R. A., M. A. Acton, and F. C. Neidhardt. 1987. Induction of the heat shock regulon does not produce thermotolerance in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 1:525-531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.VanBogelen, R. A., P. M. Kelley, and F. C. Neidhardt. 1987. Differential induction of heat shock, SOS, and oxidation stress regulons and accumulation of nucleotides in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 169:26-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.VanBogelen, R. A., and F. C. Neidhardt. 1990. Ribosomes as sensors of heat and cold shock in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:5589-5593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xiao, H., M. Kalman, K. Ikehara, S. Zemel, G. Glaser, and M. Cashel. 1991. Residual guanosine 3′,5′-bispyrophosphate synthetic activity of relA null mutants can be eliminated by spoT null mutations. J. Biol. Chem. 266:5980-5990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]