Abstract

There has been a long-standing controversy about the possibility that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants might induce suicidality in some patients. To shed light on this issue, this paper reviews available randomized controlled trials (RCTs), meta-analyses of clinical trials and epidemiological studies that have been undertaken to investigate the issue further. The original clinical studies raising concerns about SSRIs and suicide induction produced evidence of a dose-dependent link on a challenge-dechallenge and rechallenge basis between SSRIs and both agitation and suicidality. Meta-analyses of RCTs conducted around this time indicated that SSRIs may reduce suicidal ideation in some patients. These same RCTs, however, revealed an excess of suicidal acts on active treatments compared with placebo, with an odds ratio of 2.4 (95; confidence interval 1.6–3.7). This excess of suicidal acts also appears in epidemiological studies. The data reviewed here make it difficult to sustain a null hypothesis that SSRIs do not cause problems in some individuals. Further studies or further access to data are indicated to establish the magnitude of any risk and the characteristics of patients who may be most at risk.

Medical subject headings: antidepressive agents, epidemiology, meta-analysis, serotonin uptake inhibitors, suicide, treatment outcome

Abstract

La possibilité que les antidépresseurs inhibiteurs spécifiques du recaptage de la sérotonine (ISRS) entraÎnent des tendances suicidaires chez certains patients soulève la controverse depuis longtemps. En vue d'éclairer la question, cette communication passe en revue les études contrôlées et randomisées (ECR), méta-analyses d'études cliniques et études épidémiologiques disponibles que l'on a effectuées pour l'approfondir. Les premières études cliniques ayant soulevé des préoccupations au sujet des ISRS et des tendances suicidaires ont produit des données probantes établissant un lien lié à la dose entre les ISRS et deux symptômes, l'agitation et les tendances suicidaires, suivant l'administration du médicament, la cessation, puis la reprise du traitement. Des méta-analyses des ECR réalisées à l'époque ont indiqué que les ISRS pourraient réduire les idées suicidaires chez certains patients. Ces mêmes ECR ont néanmoins révélé des actes suicidaires en surnombre dans le groupe de traitement actif, par rapport au placebo. À cet égard, le coefficient de probabilité s'est établi à 2,4 (intervalle de confiance à 95 %, 1,6–3,7). Des études épidémiologiques ont aussi révélé des actes suicidaires en surnombre. Compte tenu des données examinées, il est difficile de soutenir l'hypothèse nulle voulant que les ISRS n'entraÎnent pas de problèmes chez certaines personnes. La réalisation de nouvelles études ou la diffusion d'autres données sont indiquées pour établir l'importance du risque et les caractéristiques des patients susceptibles d'être les plus vulnérables.

Introduction

The debate regarding selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and suicide started in 1990, when Teicher, Glod and Cole1 described 6 cases in which intense suicidal preoccupation emerged during fluoxetine treatment. This paper was followed by others,2,3,4,5,6 which, combined, provided evidence of dose–response, challenge, dechallenge and rechallenge relations, as well as the emergence of an agreed mechanism by which the effects were mediated and demonstrations that interventions in the process could ameliorate the problems. A subsequent series of reports on the effects of sertraline and paroxetine on suicidality and akathisia pointed to SSRI-induced suicidality being a class effect rather than something confined to fluoxetine.7

An induction of suicidality by SSRIs, therefore, had apparently been convincingly demonstrated according to conventional criteria for establishing cause and effect relations between drugs and adverse events, as laid out by clinical trial methodologists, company investigators, medico-legal authorities and the federal courts.8 Far less consistent evidence led the Medicines Control Agency in Britain in 1988 to state unambiguously that benzodiazepines can trigger suicide.9

Specifically designed randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on depression-related suicidality at this time would have established the rates at which this seemingly new phenomenon might be happening. However, no such studies have ever been undertaken. This review, therefore, will in lieu cover the RCT data on newly released antidepressants and suicidal acts, the meta-analyses of efficacy studies in depression that have been brought to bear on the question and relevant epidemiological studies.

Efficacy studies

In lieu of specifically designed RCTs, the RCTs that formed the basis for the licence application for recent antidepressants are one source of data. Khan and colleagues10 recently analyzed RCT data to assess whether it was ethical to continue using placebos in antidepressant trials. Although the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), in general, recommend that data from clinical trials be analyzed both in terms of absolute numbers and patient exposure years (PEY), given that an assessment of the hazards posed by placebo was the object of this study, the investigators appropriately analyzed the figures in terms of PEY only. Khan et al10 found an excess of suicidal acts by individuals taking antidepressants compared with placebo, and this was also replicated in another analysis,11 but the rates of suicidal acts in patients taking antidepressants and those taking placebo were not significantly different in these analyses. Yet, another study12 reported that rates of suicidal acts of patients taking antidepressants for longer durations may, in fact, fall relative to placebo, which might be expected because longer term studies will select patients suited to the agent being investigated.

Although an analysis in terms of PEYs may be appropriate for an assessment of the risk of exposure to placebo, it is inappropriate for the assessment of a problem that clinical studies had clearly linked to the first weeks of active therapy. An analysis of suicidal acts on the basis of duration of exposure systematically selects patients who do not have the problem under investigation, because those with the problem often drop out of the trial, whereas others who do well are kept on treatment for months or more on grounds of compassionate use.

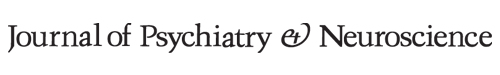

The data presented by Khan and colleagues10 has accordingly been modified here in 4 respects (Table 1). First, suicides and suicidal acts are presented in terms of absolute numbers of patients. Second, on the basis of an FDA paroxetine safety review13 and FDA statistical reviews on sertraline,14 it is clear that some of the suicides and suicidal acts categorized as occurring while patients were taking placebo actually occurred during a placebo washout period; placebo and washout suicides are therefore distinguished here. Third, data for citalopram, from another article by Khan et al,15 are included (although no details about the validity of assignments to placebo are available). Fourth, fluoxetine data from public domain documents are presented, again dividing the data into placebo and washout period suicidal acts, along with data for venlafaxine.16

Table 1

When washout and placebo data are separated and analyzed in terms of suicidal acts per patient (excluding missing bupropion data) using an exact Mantel–Haenszel procedure with a 1-tailed test for significance, the odds ratio of a suicide while taking these new antidepressants as a group compared with placebo is 4.40 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.32–infinity; p = 0.0125). The odds ratio for a suicidal act while taking these antidepressants compared with placebo is 2.39 (95% CI 1.66–infinity; p ≤ 0.0001). The odds ratio for a completed suicide while taking an SSRI antidepressant (including venlafaxine) compared with placebo is 2.46 (95% CI 0.71–infinity; p = 0.16), and the odds ratio for a suicidal act while taking SSRIs compared with placebo is 2.22 (95% CI 1.47–infinity; p ≤ 0.001).

If washout suicidal acts are included with placebo, as the companies appear to have done, but adjusting the denominator appropriately, the relative risk of suicidal acts while taking sertraline, paroxetine or fluoxetine compared with placebo becomes significant, with figures ranging from 3.0 for sertraline to over 10.0 for fluoxetine.

Other data sets yield similar findings. For instance, in Pierre Fabre's clinical trial database of approximately 8000 patients, the rate for suicidal acts by those taking SSRIs appears to be 3 times the rate for other antidepressants.17 However, these other data sets include a mixture of trials. The current analysis limits the number of studies but ensures that they are roughly comparable, and the selection of studies is based on regulatory requirements rather than individual bias.

Meta- and other analyses of SSRIs and suicidal acts

In addition to the RCT data indicating an excess of suicidal acts by those taking SSRIs, the clinical trials on zimelidine, the first SSRI, suggested there were more suicide attempts by patients taking it than by those taking comparators, but Montgomery and colleagues18 reported that although this might be the case, zimelidine appeared to do better than comparators in reducing already existing suicidal thoughts. A similar analysis demonstrated lower suicide attempt rates for those taking fluvoxamine than the comparators in clinical trials.19 Problems with paroxetine led to similar analyses and similar claims.20,21

The best-known analysis of this type was published by Eli Lilly after the controversy with fluoxetine emerged; from the analysis of pooled data from 17 double-blind clinical trials in patients with major depressive disorder, the authors concluded that “data from these trials do not show that fluoxetine is associated with an increased risk of suicidal acts or emergence of substantial suicidal thoughts among depressed patients.”22 There are a number of methodological problems with Lilly's analysis, however, and these apply to some extent to all other such exercises. First, none of the studies in the analysis were designed to test whether fluoxetine could be associated with the emergence of suicidality. In the case of fluoxetine, all of the studies had been conducted before concerns of suicide induction had arisen. Some of the studies used in the analysis had, in fact, been rejected by the FDA. Second, only 3067 patients of the approximately 26 000 patients entered into clinical trials of fluoxetine were included in this meta-analysis. Third, no mention was made of the fact that benzodiazepines had been co-prescribed in the clinical trial program to minimize the agitation that Lilly recognized fluoxetine could cause.8 Fourth, no reference was made to the 5% of patients who dropped out because of anxiety and agitation. Given that this was arguably the very problem that was at the heart of the issue, the handling of this issue was not reassuring. The 5% dropout rate for agitation or akathisia holds true for other SSRIs as well, and the differences between SSRIs and placebo are statistically significant. Given that the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition, text revision (DSM-IV-TR) has connected akathisia with suicide risk, this point is of importance.23

Finally, this and other analyses depend critically on item 3 (i.e., suicide) of the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; this approach to the problem is one that FDA officials, Lilly personnel and Lilly's consultants8 agreed was methodologically unsatisfactory. The argument in these meta-analyses has, broadly speaking, been that in the randomized trials, the SSRI reduced suicidality on item 3 and that there was no emergence of suicidality, as measured by this item. To claim that the prevention of or reduction of suicidality in some patients in some way means that treatment cannot produce suicidality in others is a logical non sequitur. The argument that item 3 would pick up emergent suicidality in studies run by clinicians who are not aware of this possible adverse effect has no evidence to support it.

Despite these methodological caveats, the claim that SSRIs reduce suicidality in some patients appears strong. However, insofar as SSRIs reduce suicidal acts in some, if there is a net increase in suicidal acts associated with SSRI treatment in these same trials, the extent to which SSRIs cause problems for some patients must be greater than is apparent from considering the raw data.

Epidemiological studies

Epidemiology traditionally involves the study of representative samples of the population and requires a specification of the methods used to make the sample representative. A series of what have been termed epidemiological studies have been appealed to in this debate. The first is a 1-column letter involving no suicides.24 The second is a selective retrospective post-marketing chart review25 involving no suicides, which analyzed by the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, the FDA and others,26,27 shows a 3-fold increased relative risk of emergent suicidality for fluoxetine versus other antidepressants.

A third study was conducted by Warshaw and Keller28 on patients with anxiety disorder, in which the only suicide was committed by a patient taking fluoxetine. However, only 192 of the 654 patients in this study received fluoxetine. This, therefore, was not a study designed to test fluoxetine's capacity to induce suicidality. In a fourth study of 643 patients, conceived 20 years before fluoxetine was launched and instituted 10 years before launch, only 185 patients received fluoxetine at any point.29 This was clearly not a study designed to establish whether fluoxetine might induce suicidality. None of these studies fit the definition of epidemiology offered above.

Although not properly epidemiological, 2 post-marketing surveillance studies that compared SSRI with non-SSRI antidepressants found a higher rate of induction of suicidal ideation for those taking SSRIs, although not in the rates of suicidal acts or suicides.30,31

In a more standard epidemiological study of 222 suicides, Donovan et al32 reported that 41 of those suicides were committed by people who had been taking an antidepressant in the month before their suicide; there was a statistically significant doubling of the relative risk of suicide in those taking SSRIs compared with tricyclic antidepressants. In a further epidemiological study of 2776 acts of deliberate self-harm, Donovan et al33 found a doubling of the risk for deliberate self-harm for those taking SSRIs compared with other antidepressants.

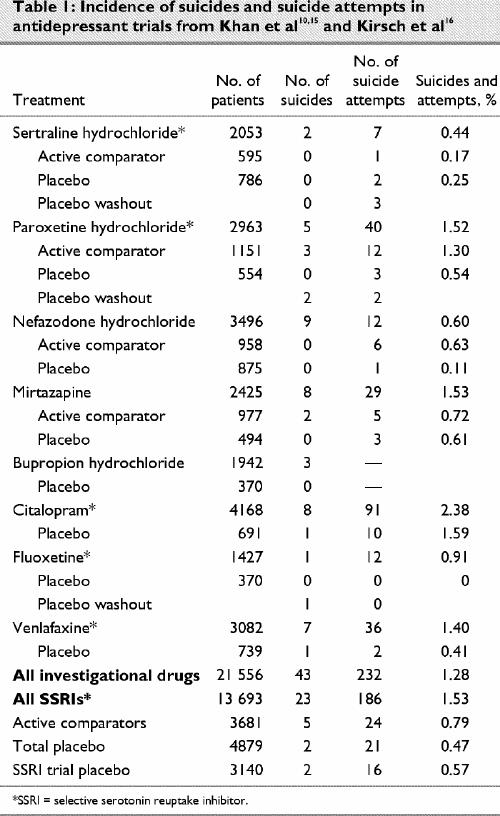

A set of post-marketing surveillance studies carried out in primary care in the United Kingdom by the Drug Safety Research Unit (DSRU)34 recorded 110 suicides in over 50 000 patients being treated by general practitioners in Britain. The DSRU methodology has since been applied to mirtazapine, where there have been 13 suicides reported in a population of 13 554 patients.35 This permits the comparisons outlined in Table 2.

Table 2

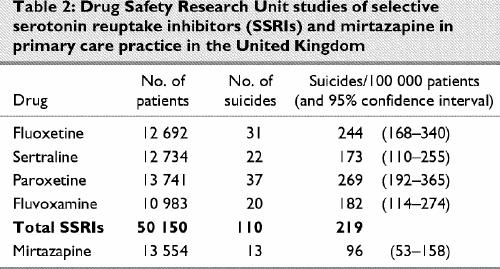

A further study from British primary care was undertaken by Jick and colleagues,36 who investigated the rate and means of suicide among people taking common antidepressants. They reported 143 suicides among 172 580 patients taking antidepressants and found a statistically significant doubling of the relative risk of suicide with fluoxetine compared with the reference antidepressant, dothiepin, when calculated in terms of patient exposure years. Controlling for confounding factors such as age, sex and previous suicide attempts left the relative risk at 2.1 times greater for fluoxetine than for dothiepin and greater than any other antidepressant studied, although statistical significance was lost in the process. Of further note are the elevated figures for mianserin and trazodone, which are closely related pharmacologically to mirtazapine and nefazodone. Controlling for confounding factors in the case of mianserin and trazodone, however, led to a reduction in the relative risk of these agents compared with dothiepin.

To provide comparability with other figures, I have recalculated these data in terms of absolute numbers and separated the data for fluoxetine (Table 3). The data in the Jick study, however, only allow comparisons between antidepressants.36 They shed no light on the differences between treatment with antidepressants and non-treatment or on the efficacy of antidepressants in reducing suicide risk in primary care. The traditional figures with which the DSRU studies and the Jick study might be compared are a 15% lifetime risk for suicide for affective disorders. This would be inappropriate, however, because this 15% figure was derived from patients with melancholic depression in hospital in the pre-antidepressant era.

Table 3

There are very few empirical figures available for suicide rates in primary care depression, the sample from which the Jick et al36 and DSRU34 data come. One study from Sweden37 reports a suicide rate of 0 per 100 000 patients in non-hospitalized depression. Another primary care study from the Netherlands gives a suicide rate of 33 per 100 000 patient years.38 Finally, Simon and VonKorff39 in a study of suicide mortality among individuals treated for depression in Puget Sound, Wash., reported 36 suicides in 62 159 patient years. The suicide risk per 100 000 patient years was 64 among those who received outpatient specialty mental health treatment, 43 among those treated with antidepressant medications in primary care and 0 among those treated in primary care without antidepressants.

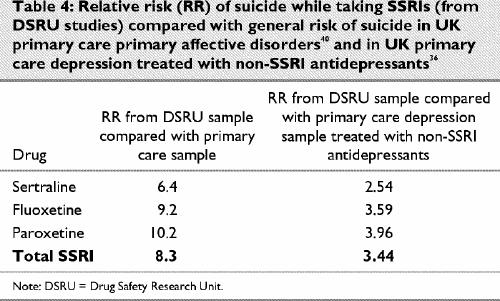

Utilizing a database of 2.5 million person years and 212 suicides from North Staffordshire, Boardman and Healy40 modelled the rate for suicide in treated or untreated depression and found it to be of the order of 68/100 000 patient years for all affective disorders.40 This rate gives an upper limit on the suicide rate in mood disorders that is compatible with observed national rates of suicide in the United Kingdom. Boardman and Healy estimate a rate of 27 suicides per 100 000 patients per annum for primary care primary affective disorders. Possible relative risks for SSRIs from the DSRU studies set against these figures and the findings from the Jick study for all antidepressants excluding fluoxetine are presented in Table 4.

Table 4

Comparing the figures for SSRIs from Table 2 with those for the non-SSRI antidepressants from the Jick study gives a mean figure for non-SSRI antidepressants of 68 suicides per 100 000 patients exposed compared with a figure of 212 suicides for the SSRI group. Based on an analysis of 249 803 exposures to antidepressants, therefore, the broad relative risk on SSRI antidepressants compared with non-SSRI antidepressants or even non-treatment is 234/68 or 3.44.

There are 2 points of note. First, these low rates for suicide in untreated primary care mood disorder populations are consistent with the rate of 0 suicides in those taking placebo in antidepressant RCTs. Second, correcting the DSRU figures for exposure lengths gives figures for suicides on sertraline and paroxetine comparable to those reported from RCTs by Khan et al.10

Conclusion

Since antidepressant drug treatments were introduced, there have been concerns that their use may lead to suicide.41 Hitherto, there has been a legitimate public health concern that the debate about possible hazards might deter people at risk from suicide from seeking treatment, possibly leading to an increased number of suicides. The data reviewed here, however, suggest that warnings and monitoring are more likely to reduce overall risks or that at least we should adopt a position of clinical equipoise on this issue and resolve it by means of further study rather than on the basis of speculation.

The evidence that antidepressants may reduce suicide risk is strong from both clinical practice and RCTs. An optimal suicide reduction strategy would probably involve the monitored treatment of all patients and some restriction of treatment for those most at risk of suicide. In addition, given evidence that particular personality types suit particular selective agents and that mismatching patients and treatments can cause problems,42 further exploration of this area would seem called for.

See related article page 340

Footnotes

Competing interests: In recent years, Dr. Healy has had consultancies with, been a principal investigator or clinical trialist for, been a chairman or speaker at international symposia for or been in receipt of support to attend meetings from: Astra-Zeneca, Boots/Knoll Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly, Janssen-Cilag, Lorex-Synthelabo, Lundbeck, Organon, Pharmacia & Upjohn, Pierre-Fabre, Pfizer, Rhone-Poulenc Rorer, Roche, SmithKline Beecham and Solvay. In the past 2 years, he has had lecture fees and support to attend meetings from Astra-Zeneca, and he has been an expert witness for the plaintiff in 4 legal actions invoving SSRIs. He has also been consulted on a number of other attempted suicide, suicide and suicide–homicide cases following antidepressant treatment, in the majority of which he has offered the view that the treatment was not involved. He has also been an expert witness for the National Health Service (NHS) in a series of LSD (46) and ECT (1) cases.

Correspondence to: Dr. David Healy, Department of Psychological Medicine, University of Wales College of Medicine, Hergest Unit, Bangor, LL57 2PW United Kingdom; fax 44 1248 371397; Healy_Hergest@compuserve.com

Submitted Oct. 17, 2001 Revised Apr. 4, 2003; May 30, 2003 Accepted June 3, 2003

References

- 1.Teicher MH, Glod C, Cole JO. Emergence of intense suicidal preoccupation during fluoxetine treatment. Am J Psychiatry 1990;147:207-10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.King RA, Riddle MA, Chappell PB, Hardin MT, Anderson GM, Lombroso P. Emergence of self-destructive phenomena in children and adolescents during fluoxetine treatment. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1991;30:171-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Masand P, Gupta S, Dwan M. Suicidal ideation related to fluoxetine treatment [letter]. N Engl J Med 1991;324:420. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Rothschild AJ, Locke CA. Re-exposure to fluoxetine after serious suicide attempts by 3 patients: the role of akathisia. J Clin Psychiatry 1991;52:491-3. [PubMed]

- 5.Creaney W, Murray I, Healy D. Antidepressant induced suicidal ideation. Hum Psychopharmacol 1991;6:329-32.

- 6.Wirshing WC, Van Putten T, Rosenberg J, Marder S, Ames D, Hicks-Gray T. Fluoxetine, akathisia and suicidality: is there a causal connection? Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992;49:580-1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Lane RM. SSRI-induced extrapyramidal side effects and akathisia: implications for treatment. J Psychopharmacology 1998; 12: 192-214. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Healy D. A failure to warn [editorial]. Int J Risk Safety Med 1999; 12:151-6.

- 9.Committee on Safety of Medicines. Current problems (no. 21). Guidance on benzodiazepines. London (UK): Committee on Safety of Medicines and the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency; Jan. 1988.

- 10.Khan A, Warner HA, Brown WA. Symptom reduction and suicide risk in patients treated with placebo in antidepressant clinical trials. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000;57:311-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Laughren TP. The scientific and ethical basis for placebo-controlled trials in depression and schizophrenia: an FDA perspective. Eur Psychiatry 2001;16:418-23. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Storosum JG, van Zwieten BJ, van den Brink W, Gersons BP, Broekman AW. Suicide risk in placebo-controlled studies of major depression. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158:1271-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Brecher M. FDA Review and Evaluation of Clinical Data Original NDA 20-021, Paroxetine Safety Review. 1991 Jun 19.

- 14.Lee H. Statistical reviews on sertraline for FDA. 1990 Aug 14 and 1991 Jan 31.

- 15.Khan A, Khan SR, Leventhal RM, Brown WA. Symptom reduction and suicide risk in patients treated with placebo in antidepressant clinical trials: a replication analysis of the Food and Drug Administration database. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2001; 4:113-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Kirsch I, Moore TJ, Scoboria A, Nicholls SS. The emperor's new drugs: an analysis of antidepressant medication data submitted to the US Food and Drug Administration. Prevention and Treatment 2002;5:Article 23. Posted 15 Jul 2002. Available: www.journals.apa.org/prevention/volume5/pre0050023a.html (accessed 16 Jul 2003).

- 17.Kasper S. The place of milnacipran in the treatment of depression. Hum Psychopharmacol 1997;12:S135-41.

- 18.Montgomery SA, McAulay R, Rani SJ, Roy D, Montgomery DB. A double-blind comparison of zimelidine and amitriptyline in endogenous depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1981;63 (Suppl 290):314-27. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Wakelin JS. The role of serotonin in depression and suicide. Do serotonin reuptake inhibitors provide a key? In: Gastpar M, Wakelin JS, editors. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: novel or commonplace agents. Basel: Karger; 1988. p. 70-83.

- 20.Lopez-Ibor JJ. Reduced suicidality on paroxetine. Eur Psychiatry 1993;1(Suppl 8):S17-9.

- 21.Montgomery SA, Dunner DL, Dunbar G. Reduction of suicidal thoughts with paroxetine in comparison to reference antidepressants and placebo. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 1995;5:5-13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Beasley CM, Dornseif BE, Bosomworth JC, Sayler ME, Rampey AH, Heiligenstein JH, et al. Fluoxetine and suicide: a meta-analysis of controlled trials of treatment for depression. BMJ 1991;303:685-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth ed., text rev. Washington: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. p. 801.

- 24.Ashleigh EA, Fesler FA. Fluoxetine and suicidal preoccupation [letter]. Am J Psychiatry 1992;149:1750. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Fava M, Rosenbaum JF. Suicidality and fluoxetine: is there a relationship? J Clin Psychiatry 1991;52:108-11. [PubMed]

- 26.American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. Suicidal behavior and psychotropic medication. Neuropsychopharmacology 1992;8:177-83. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Teicher MH, Glod CA, Cole JO. Antidepressant drugs and the emergence of suicidal tendencies. Drug Safety 1993;8:186-212. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Warshaw MG, Keller MB. The relationship between fluoxetine use and suicidal behavior in 654 subjects with anxiety disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 1996;57:158-66. [PubMed]

- 29.Leon AC, Keller MB, Warshaw MG, Mueller TI, Solomon DA, Coryell W. Prospective study of fluoxetine treatment and suicidal behavior in affectively ill subjects. Am J Psychiatry 1999;156:195-201. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Fisher S, Bryant SG, Kent TA. Postmarketing surveillance by patient self-monitoring: trazodone versus fluoxetine. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1993;13:235-42. [PubMed]

- 31.Fisher S, Kent TA, Bryant SG. Postmarketing surveillance by patient self-monitoring: preliminary data for sertraline versus fluoxetine. J Clin Psychiatry 1995;56:288-96. [PubMed]

- 32.Donovan S, Kelleher MJ, Lambourn J, Foster R. The occurrence of suicide following the prescription of antidepressant drugs. Arch Suicide Res 1999;5:181-92.

- 33.Donovan S, Clayton A, Beeharry M, Jones S, Kirk C, Waters K, et al. Deliberate self-harm and antidepressant drugs. Investigation of a possible link. Brit J Psychiatry 2000;177:551-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.MacKay FJ, Dunn NR, Wilton LV, Pearce GL, Freemantle SN, Mann RD. A comparison of fluvoxamine, fluoxetine, sertraline and paroxetine examined by observational cohort studies. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 1997;6(Suppl 3):235-46. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Biswas P, Wilton LV, Shakir SAW. Pharmacovigilance of mirtazapine: results of a prescription event monitoring study of 13,554 patients in England [presentation]. Royal College of Psychiatrists Annual Meeting; 2001 Jul 9–13; London.

- 36.Jick S, Dean AD, Jick H. Antidepressants and suicide. BMJ 1995;310:215-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Hagnell O, Lanke J, Rorsman B. Suicide rates in the Lundby study: mental illness as a risk factor for suicide. Neuropsychobiology 1981;7:248-53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.van Weel-Baumgarten E, van Den Bosch W, van Den Hoogen H, Zitman FG. Ten-year follow-up of depression after diagnosis in general practice. Br J Gen Pract 1998;48:1643-6. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Simon GE, VonKorff M. Suicide mortality among patients treated for depression in an insured population. Am J Epidemiol 1998;147:155-60. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Boardman AP, Healy D. Modeling suicide risk in primary care primary affective disorders. Eur Psychiatry 2001;16:400-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Kielholz P, Battegay R. Behandlung depressiver Zustandsbilder, unter spezieller Berücksichtigung von Tofranil, einem neuen Antidepressivum. Schweiz Med Wochenschr 1958;88:763-7. [PubMed]

- 42.Tranter R, Healy H, Cattell D, Healy D. Functional variations in agents differentially selective to monoaminergic systems. Psychol Med 2002;32;517-24. [DOI] [PubMed]