Abstract

Little is known about age-related changes in red blood cell (RBC) membrane transport and homeostasis. We investigated first whether the known large variation in plasma membrane Ca2+ (PMCA) pump activity was correlated with RBC age. Glycated hemoglobin, Hb A1c, was used as a reliable age marker for normal RBCs. We found an inverse correlation between PMCA strength and Hb A1c content, indicating that PMCA activity declines monotonically with RBC age. The previously described subpopulation of high-Na+, low-density RBCs had the highest Hb A1c levels, suggesting it represents a late homeostatic condition of senescent RBCs. Thus, the normal densification process of RBCs with age must undergo late reversal, requiring a membrane permeability increase with net NaCl gain exceeding KCl loss. Activation of a nonselective cation channel, Pcat, was considered the key link in this density reversal. Investigation of Pcat properties showed that its most powerful activator was increased intracellular Ca2+. Pcat was comparably selective to Na+, K+, choline, and N-methyl-D-glucamine, indicating a fairly large, poorly selective cation permeability pathway. Based on these observations, a working hypothesis is proposed to explain the mechanism of progressive RBC densification with age and of the late reversal to a low-density condition with altered ionic gradients.

Introduction

Our recent findings of a large variation in plasma membrane Ca2+ pump (PMCA) activity of normal human red blood cells (RBCs)1 prompted the question of whether this variation was related to cell age and, if so, whether an age-related decline in PMCA activity might account for some observed changes in aging RBCs. The PMCA is the only active Ca2+ transporter in human RBCs.2–5 At saturating [Ca2+]i levels, its mean maximal Ca2+ extrusion rate, Vmax, is about 10 to 15 mmol(340 g Hb)−1h−1, whereas the normal mean pump-leak Ca2+ turnover is only about 50 μmol(340 g Hb)−1h−1.6,7 Thus, in physiological conditions the mean pump activity is a small fraction of its mean Vmax. This balance, however, is far from uniform among the RBCs, whose PMCA activity showed a broad unimodal distribution pattern, with a coefficient of variation of about 50%.1 The cells with the weaker Ca2+ pumps would have higher [Ca2+]i levels than those with stronger pumps. Because RBC [Ca2+]i levels control several transport and biochemical processes affecting volume regulation, metabolism, and rheology, the resulting variations in [Ca2+]i may generate marked differences in RBC composition. There were early indications that PMCA activity decreased with RBC age,8–10 but there has been no systematic study of the age-activity relation over the full range of pump variation observed.

Here we devised a method to segregate RBCs according to their PMCA strength to be able to measure directly the age of the segregated RBCs. We used the fraction of glycated hemoglobin, Hb A1c, as a reliable measure of RBC age.11–15 Because protein glycosylation is a nonenzymic process linear with time and glucose concentration, the Hb A1c fraction is a reliable age marker for normal human RBCs, which, unlike those of diabetic patients, are exposed to relatively stable glucose levels in vivo. In the course of investigating the age-activity relation of the PMCA we observed an unexpected reversal of the main pattern of RBC behavior, as detailed below, which could be explained by the presence of a small fraction of aged RBCs unable to dehydrate by K+ permeabilization. Such RBCs had been described before,16 but their age had not been measured. We now demonstrate that they have a high Hb A1c content, suggesting that they represent a normal terminal condition of senescent RBCs.

For a dense, low-Na+, aging RBC to change to a lesser dense, higher-Na+, terminal condition in the circulation, it must undergo a change in membrane permeability whereby net NaCl gain exceeds net KCl loss, leading to progressive net salt and water gain. A likely candidate for such a process was the nonselective cation permeability pathway originally described by Crespo et al17 as “prolytic” (following a nomenclature originally used by Ponder to describe effects of lysins on RBC homeostasis18,19). The prolytic pathway exhibited a sufficiently high Na+ permeability to exceed the extrusion capacity of the Na pump, leading to the swelling and eventual lysis of the affected RBCs. We undertook a detailed investigation of the main properties of the “prolytic” pathway, which we designate here “Pcat,” applying methods that examine the responses of the entire RBC population to the factors that activate this pathway.

Materials and methods

Approval for these studies was obtained from the institutional review boards of the University of Cambridge, United Kingdom, and from the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY.

Solutions

The main solutions used (to which specific additions were made, as noted) were (all concentrations in mM) as follows: (1) “90K”: KCl, 90; NaCl, 55; HEPES-Na, pH 7.5 at 37°C, 10, and MgCl2, 0.15; (2) “0K”: NaCl, 135; NaSCN, 10; HEPES-Na, pH 7.5 at 37°C, 10, and MgCl2, 0.15; (3) “LK”: NaCl, 132; NaSCN, 10; KCl, 3; HEPES-Na, pH 7.5 at 37°C, 10, and MgCl2, 0.15; (4) “HK”: NaSCN, 5; KSCN, 5; KCl, 135; HEPES-Na, pH 7.5 at 37°C, 10, and MgCl2, 0.15; and (5) “90K-SCN”: NaCl, 45; NaSCN, 10; KCl, 90; HEPES-Na, pH 7.5 at 37°C, 10, and MgCl2, 0.15. SCN− was used to bypass any rate-limiting effects of the anion permeability on the rate of dehydration or hydration of K+-permeabilized RBCs.20,21 Ten millimolar SCN− is sufficient to saturate this effect,22 thus avoiding the changes in the isoelectric point of impermeant cell anions and RBC hydration that are observed at higher SCN− concentrations.23 In 90K media the mean volume of K+-permeabilized RBCs remains largely unchanged (Figure 3H). The 0K medium was used to receive RBC samples suspended in 90K medium, rendering a final extracellular K+ concentration of about 3 mM. Unless specified otherwise in the legends of figures, the final concentrations of the most frequently added solutes were (in mM): NaOH-neutralized EGTA (ethylene glycol-bis(2-aminoethylether)-N,N,N,N,-tetraacetic acid), 0.1; CaCl2, 0.12; inosine, 5; ionophore A23187 (from 2 mM stock in ethanol), 0.01; and defatted bovine serum albumin, 1.5%. EGTA and CaCl2 were added from stock solutions with concentrations at least 100-fold those of the final solutions or suspensions. Inosine was dissolved as powder before additions. All chemicals were analytical reagent quality. NaSCN, KSCN, EGTA, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), HEPES, DMSO, defatted bovine serum albumin, and inosine were from Sigma-Aldrich (Munich, Germany). The ionophores A23187 and valinomycin were from Calbiochem-Novabiochem (Nottingham, United Kingdom). Diethylphthalate (DEP) oil was from Acros Organics (Geel, Belgium). CaCl2, MgCl2, NaCl, and KCl were from FSA Laboratory Supplies (Loughborough, United Kingdom).

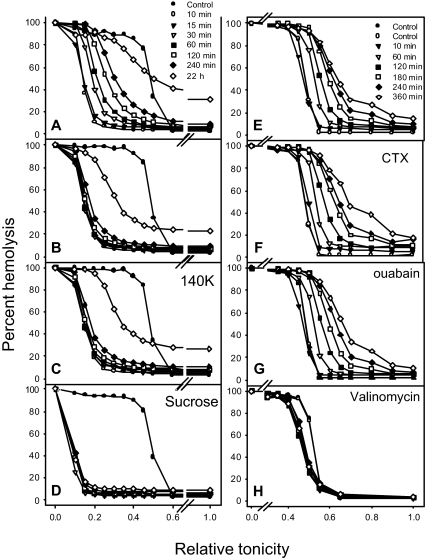

Figure 3.

Distribution of Pcat activity induced by Ca2+ loads and RBC dehydration, shown as profile migration of osmotic lysis curves. Experiments were performed at 37°C with gentle magnetic stirring of the RBC suspensions, with Hct 5% and suspension [Ca2+]o of 50 μM. All media were supplemented with 5 mM inosine and 40 μg/mL gentamicin. At t = 0, A23187 was added in panels A to G and valinomycin to panel H to final concentrations of 5 and 10 μM, respectively, in the cell suspension. (A) Rehydration response in LK medium. The indicated times apply to Figure 3A-D. The rapid left shift in the osmotic fragility curve indicates full uniform dehydration of the RBCs by 10 minutes following the ionophore-induced Ca2+ load. This is followed by slow right shifts in the osmotic fragility curves reflecting the Pcat-mediated rehydration response. (B) At t = 11 minutes, after dehydration was complete, 1 mM EGTA was added to rapidly extract cell Ca2+, reducing [Ca2+]i to subphysiological levels. RBCs exposed to 10 μM valinomycin at t = 0 instead of A23187 showed identical dehydration-rehydration patterns as those in this panel, and therefore Figure 1B is used to illustrate both experimental results. (C) At t = 11 minutes, after dehydration was complete, 1 mM EGTA was added to rapidly extract cell Ca2+, reducing [Ca2+]i to subphysiological levels. The suspension was gently spun at 900g for 3 minutes, the supernatant removed, and the cells resuspended in HK medium supplemented with 1 mM EGTA to follow the rehydration pattern in HK medium with the Gardos channels inactivated by Ca2+ removal. (D) RBCs were suspended in LK medium in which 120 mM NaCl was replaced by 240 mM sucrose. (E) Hydration response in 90K medium. The indicated times apply to panels E to H. (F) Effect of 0.1 μM charybdotoxin (CTX) on the hydration response in 90K medium. (G) Effect of 0.1 mM ouabain on the hydration response in 90K medium. (H) Effect of valinomycin instead of A23187 in the same conditions as those of Figure 3E.

Preparation of RBCs for the age-PMCA correlation study

After obtaining informed written consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, venous blood of healthy volunteers was drawn into tubes with EDTA, washed twice in ice-cold 90K solution with added EGTA, and washed twice more with solution 90K alone. The buffy coat (platelets and white cells) was removed after each wash, with special care to minimize aspiration of lighter RBCs. The washed RBCs were suspended at 10% hematocrit (Hct) in 90K supplemented with inosine and Ca2+ and temperature-equilibrated for 10 minutes at 37°C before the Ca2+-load protocol.

Preparation of RBCs for the study of Pcat properties

RBCs obtained as above were washed twice in ice-cold LK solution with added EGTA and twice more with solution LK alone. The buffy coat (platelets and white cells) was carefully aspirated after each wash to ensure near complete white cell removal. The washed RBCs were suspended at 5% Hct in LK supplemented with inosine (5 mM), gentamicin, and Ca2+, as indicated, and temperature-equilibrated for 10 minutes at 37°C before addition of ionophore. Other additions, ion replacements, as well as the specific concentrations of Ca2+, ionophores, and inhibitors used in the experiments are indicated in the figure legends.

Protocol to segregate RBCs according to PMCA strength

We designed the following method to separate RBCs according to their maximal Ca2+ extrusion capacity (PMCA Vmax). The RBCs were rapidly and uniformly loaded with about 500 μmol(340 g Hb)−1 of total Ca2+, [CaT]i, by addition of 10 μM ionophore A23187 to the 10% Hct suspension containing 120 μM external Ca2+, [Ca2+]o. The 90K medium prevented net K+ fluxes via Ca2+-activated Gardos channels,24 thus preserving the original RBC volumes.25 After 2 minutes to allow Ca2+ equilibration, the ionophore was extracted to restore the original low-membrane Ca2+ permeability by transferring the suspension into 10 volumes of stirred, ice-cold 90K medium with 1.5% albumin. The low temperature inhibited the PMCA, trapping the original RBC Ca2+ load.1,26 The suspension was spun at 2500g for 5 minutes at 0°C. The RBC pellets were pooled and washed twice more at 0°C in solution 90K with albumin and thrice in 90K alone.

The washed, ionophore-free packed RBCs (about 75% Hct) were resuspended (final Hct, about 14%) in 90K medium supplemented with inosine in a magnetically stirred glass vial in a water bath at 37°C; this immediately reactivated Ca2+ extrusion27 (t = 0) at the pump Vmax rate of each RBC. At 15- to 30-second intervals, 0.5 mL samples of this suspension were delivered into tubes containing 12 mL of 0K medium at 0°C to 4°C to instantly block further RBC Ca2+ extrusion and trap their residual Ca2+ content. Because Gardos channels have a relatively low temperature dependence,26,28 dilution into 0K medium triggered rapid dehydration of any RBCs containing sufficient Ca2+ to activate the channels. After 40 minutes in the ice bath to allow maximal dehydration of the Ca2+-containing RBCs, the tubes were centrifuged and the RBCs were resuspended in 1 mL of 0K medium at 20°C, layered onto 0.4 mL of DEP oil (1.117 g/mL) in 1.5 mL microfuge tubes, and spun 1 minute at 10 000g. The Ca2+-free RBCs above the oil and the pelleted dense cells still containing Ca2+ were harvested into microfuge tubes by gentle resuspension in 0K medium and sampled for Hb to estimate their yields. After centrifugation the RBC pellets were refrigerated for 24 to 48 hours or frozen for later determination of Hb A1c.

This method provided a cumulative separation of RBCs with a PMCA Vmax above or below a given value at each time point. In the earliest samples nearly all the RBCs would be in the pellets but, with time, increasing proportions of RBCs would have extruded their Ca2+ and would remain on top of the oil. Hb A1c measurements required at least 2.5 to 3 μL of RBCs, and when the yields (from the top and bottom of the oil layer in the initial and final samples, respectively) were too small to measure Hb A1c, the RBCs harvested over 2 consecutive sampling periods were pooled.

Measurements of the Hb concentration, [Hb], and of Hb A1c

[Hb] was determined in RBC lysates by light absorption at 415 nm, the Soret band, using a plate reader (Spectramax 190; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). When RBCs were segregated according to PMCA activity, the Hb yields of the separated fractions were expressed as a percent of the total Hb in the unfractionated sample. For osmotic fragility curves, the lysis at each relative tonicity was expressed as a percent of the lysis in distilled water. Hb A1c was measured on code-labeled samples by ion exchange HPLC12,29 at the Biochemistry Laboratories, Addenbrooke's Hospital, Cambridge, United Kingdom (project 719) and at the Jacobi Medical Center, Bronx, NY, using Variant II instruments (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Reproducibility of the Hb A1c measurements was estimated on 20 aliquots of a single blood sample, whose mean ± standard deviation was 5.71% ± 0.02%, giving a coefficient of variation of 0.35%. Thus, the intrinsic measurement error of the reported Hb A1c values is within the size of the points in the figures below. Preliminary experiments (not shown) using Co2+ instead of albumin washes27 to terminate ionophore-mediated Ca2+ fluxes30 showed that Co2+ alters the size and shape of the Hb A1c peaks, suggesting that Co2+ might crosslink Hb with some other cell or lysate component that coeluted with genuine glycosylated Hb A1c. This precluded Co2+ use when measuring Hb A1c. Similar tests with variable Ca2+ concentrations showed no such effects.

Separation of the small subpopulation of high-Na+ RBCs; measurement of yield, Hb A1c, and Na+ contents

Because segregation of RBCs according to their PMCA Vmax involved cell separation across a density boundary after K+ permeabilization, it was important to distinguish any fraction of K+-permeabilized RBCs unable to dehydrate to levels exceeding that boundary for reasons unrelated to their Ca2+ pump activity (ie, the low-density, high-Na+ RBCs).16 These low-density RBCs were found in blood from healthy subjects and in much higher proportions in blood from sickle cell anemia (SS) and thalassemia patients.16,31–33 Depending on whether the observed resistance to dehydration followed K+ permeabilization induced by valinomycin, or via Gardos channels24 following Ca2+ loads, they were named “valres” or “calres” cells, respectively. To separate calres cells, LK-washed RBCs were suspended at 10% Hct in LK medium containing 3 mM KCl and 50 μM CaCl2 and incubated at 37°C. After temperature equilibration, the ionophore A23187 was added to a final suspension concentration of 10 μM. After 10 minutes to allow maximal dehydration, 1.4 mL aliquots of this suspension were layered over 0.5 mL of DEP oil in 2 mL microfuge tubes, spun for 1 minutes at 10000g, and the tiny fractions of calres RBCs on top of the oil harvested and pooled using LK medium. Yields of calres RBCs and their Hb A1c fraction were measured directly in this suspension as described above for PMCA-separated samples. For Na+-K+ measurements the cells were washed 3 times in 10 volumes of isotonic MgCl2, lysed, and diluted in distilled water to the required optimal reading range and measured by flame photometry (Corning model 455, Surrey, United Kingdom).

Experimental protocol for the study of Pcat properties

RBC dehydration was previously described as the main trigger of Pcat.17 Accordingly, the experimental design was first to uniformly dehydrate all RBCs of any given sample and then follow their pattern and rate of rehydration from the timed changes in the profile of migrating osmotic fragility curves. The LK(+ Ca2+)-suspended RBCs (5% Hct) were K+-permeabilized by the addition of valinomycin or A23187 at t = 0 and were maximally dehydrated in 10 minutes. Samples of 0.5 mL were taken at varying time intervals up to 22 hours and processed for Na+-K+ contents, as described above, and for osmotic fragility. Variations of the basic protocol are described in “Results” and in each of the figures. Osmotic fragility was measured by the profile migration method, as previously described.34,35 The osmotic fragility curves represent the integrals of population distributions19 and are shown in standard format, plotting the percent hemolysis as a function of relative tonicity.

Results

Relation between PMCA activity and RBC age

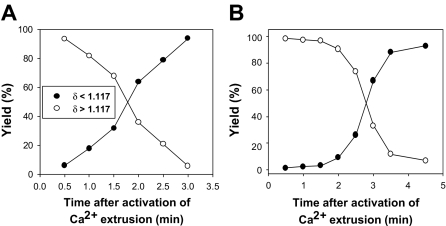

Figure 1 shows the patterns of yield recovery for RBCs that had fully extruded their Ca2+ load (δ less than 1.117, harvested from the top of the DEP oil), or had not yet done so (δ more than 1.117, harvested from pellets), at each time interval after temperature activation of PMCA-mediated Ca2+ extrusion. The results are typical of 9 experiments with blood from 6 donors. The selected results (Figure 1) exemplify the 2 patterns observed, differing mainly in the rate of increase in the yield of light RBCs (filled symbols). This rate reflects differences in the fraction of fast-pumping RBCs in samples from different donors, with faster-climbing yields of light RBCs indicating a greater fraction of high-Vmax cells. The time required for full Ca2+ extrusion varied from 2 to 4.5 minutes in these experiments. Even at the earliest sampling time (30 seconds), the fraction of cells with δ less than 1.117 was never 0 but varied between 1.5% and 5%. With an initial Ca2+ load of about 500 μmol(340 g Hb)−1, the RBCs would require pumping rates of over 60 mmol(340 g Hb)−1h−1 to fully extrude this load in less than 30 seconds. We see below that such high-pumping cells account for only part of the RBCs in these early light fractions.

Figure 1.

Representative patterns of light and dense RBC recovery as a function of time after onset of Ca2+ pump activation. The ordinate reports the percent of RBCs harvested from the top of the DEP oil (●, δ less than 1.117) or from the pellet under the oil (○, δ more than 1.117) after secondary incubation in cold 0K medium. Time = 0 is the moment the Ca2+-loaded, ionophore-free RBCs were diluted into medium 90K at 37°C to activate Ca2+ extrusion by the PMCA. The pattern in panel A was observed in 7 of the 9 experiments of this series.

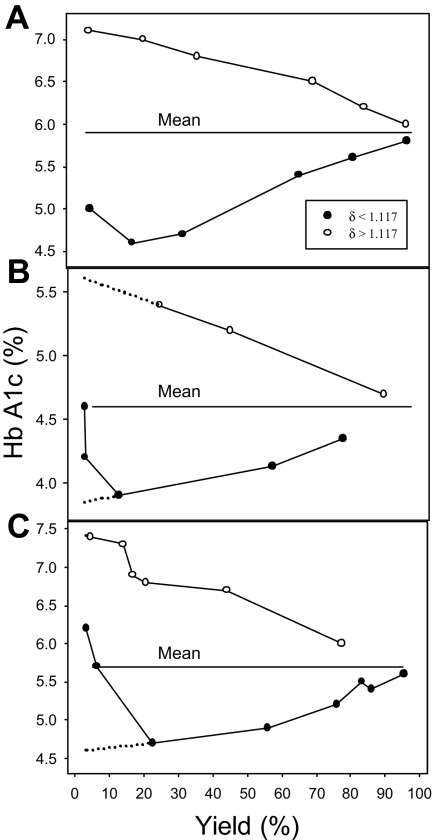

The relation between PMCA activity and RBC age is shown in Figure 2. The percent Hb A1c is plotted as a function of the yields of light (δ less than 1.117) and dense (δ more than 1.117) RBCs. The 3 results shown illustrate the patterns observed in 9 experiments. All experiments showed a clear divergent pattern toward both higher and lower Hb A1c values at decreasing yields of dense and light cells, respectively, differing only in the extent of reversal in the Hb A1c decline of the light cells at the lowest yields of light RBCs. We analyze first the significance of the divergent patterns and then consider the reason for the reversal.

Figure 2.

Percent Hb A1c in RBC fractions harvested from the top and bottom of the DEP oil, as a function of RBC yield. ●, RBCs with δ less than 1.117, harvested from the top of the oil; ○, RBCs with δ more than 1.117, harvested from the pellets under the oil. The panels represent the 3 patterns observed in the 9 experiments of this series. The only significant difference is in the extent of reversal in the pattern of declining Hb A1c with decreasing yield of light RBCs, which is analyzed in the text. The dotted lines in panels B and C represent extrapolated Hb A1c values at vanishingly small yields, pointing to the values expected among the youngest RBC fractions (lowest Hb A1c) and oldest RBC fractions (calres cells, highest Hb A1c).

The patterns in Figure 2 are precisely those expected from a progressive decline in the PMCA activity with RBC age. The RBCs harvested from pellets at the latest times after pump activation are those with the weakest pumps, represented by the points approaching the lowest yields (δ more than 1.117) with the highest Hb A1c values, indicating their older age. The quasilinear trend of increasing Hb A1c values of dense cells with decreasing yields shows that the decline in PMCA activity is an approximate linear function of RBC age. The mirror image variation in Hb A1c with yield of the light RBCs (δ less than 1.117) demonstrates the reciprocal trend, a progressive increase in PMCA activity with increasing RBC youth.

The reversal of the downward trend in the Hb A1c values observed at the lowest yields of light RBCs (δ less than 1.117) was seen in all experiments, varying only in magnitude (compare Figure 2A-C). A “contaminant” presence of high-Na+“calres” RBCs,16 unable to dehydrate to densities above 1.117 g/mL by K+ permeabilization, was an obvious candidate to explain the observed reversal, if those RBCs had high Hb A1c levels. Measurements in 14 blood samples from 7 different donors showed Hb A1c levels (mean ± SEM) of 8.19% ± 0.9% and yields of calres RBCs of 3.2% ± 1.1%. The mean Hb A1c in the unfractionated controls was 5.77% ± 0.06%. The Na+ content of calres cells was measured in 5 samples from a single donor from blood drawn on different days; the Na+ content of the calres cells was (mean ± SEM) 51.6 ± 4.3 mmol(340 g Hb)−1, whereas that of the unfractionated cells was 10.0 ± 0.1. Thus, calres RBCs from healthy donors had the high Hb A1c and Na+ contents, which could explain the observed reversal as a variable mix of low and high Hb A1c cells. Together with the early observations,16 the present results show that senescent RBCs reverse their progressive densification process toward a low-density, low-K+, high-Na+ condition, requiring a change in their normal cation permeability properties.

The properties of Pcat

In preliminary experiments with the profile migration method, we confirmed many of the results of Crespo et al17: the elevated permeability of Pcat to Na+ and K+ and the lack of effect of many transport inhibitors (ouabain, amiloride, bumetanide, furosemide, tetrodotoxin, chlorpromazine, trifluoroperazine, oligomycin, mepacrine, and tetracaine). We also found that quinine was partially inhibitory (50% inhibition at 1 mM), that clotrimazole and vanadate were slightly stimulatory, and that iodoacetic acid and N-ethyl maleimide (NEM), known inhibitors of a nonspecific, voltage-dependent channel of RBC membranes (NSVDC),36–39 had no effect. These results are not detailed here. We focus rather on results that provide additional new information about Pcat properties.

Figure 3A illustrates the screening test applied to expose Pcat using the profile migration protocol. A sudden Ca2+ load produced uniform dehydration of the RBCs, seen as a rapid, marked, and largely parallel left shift in the osmotic fragility curve; after 10 minutes, the RBCs have attained near-maximal dehydration. If they retained their normal Na+ permeability, they would remain in this dehydrated state indefinitely, as seen in Figure 3D, in which 120 mM external NaCl was isosmotically replaced by 240 mM sucrose. In high-Na+ media (Figure 3A), however, the osmotic fragility curves showed a slow and persistent right shift, eventually leading to the lysis of many RBCs. Unlike the largely uniform initial left shift, the right shifts occurred with progressively lower slopes of the osmotic fragility curves; thus, all the RBCs underwent rehydration, but their rehydration rates showed a continuous variation, with no sharp discontinuities. Thus, the extent of Pcat activation was variable among the RBCs, causing some to lyse in 1 to 3 hours and others after 20 hours (Figures 3A-C, E-G). The clear distinction between dehydration and rehydration processes shown here in the presence of SCN− could not be seen so distinctly in the absence of SCN−, when dehydration, rate-limited by the Cl− permeability, was much slower. However, the long-term rehydration pattern was identical with and without SCN− (not shown), indicating that prolonged exposure to 10 mM SCN− had no effect on the rehydration response.

To investigate whether the observed variations in Pcat were related to RBC age, Hb A1c was measured in RBCs exposed to the dehydration-rehydration protocol of Figure 3A before and after prolonged incubations (6 to 22 hours). If RBC age correlated with the rehydration rate, the Hb A1c levels of the unlysed cells recovered after prolonged incubations would have differed from the original mean level. In 4 experiments with blood from 3 donors, the differences between mean Hb A1c percents in controls and unlysed cells recovered at late times, after lysis of 25% to 42% of the cells, were 0, 0.1, 0, and -0.1, averaging 0.00% ± 0.04% (SEM). Thus, at least for most of the RBCs, age was not a significant determinant of the observed differences in hydration rate and hence of Pcat activation. These results do not exclude the possibility that small subpopulations of aged or young RBCs were among those lysing first due to a high Pcat response.

Comparison of Figure 3A and B shows that after similar dehydration the rate of rehydration was much faster when intracellular Ca2+ was increased. Rapid extraction of the RBCs' Ca2+ load by addition of Na-EGTA in large excess over [Ca2+]o at t = 10 minutes, after the cells had dehydrated, markedly reduced the rate of rehydration in both high-Na+ (Figure 3B) and high-K+ media (Figure 3C) but did not inhibit it completely. Figure 3B also illustrates the response of RBCs dehydrated with valinomycin in the absence of Ca2+ loads. Thus, the minor level of Pcat activation observed after Ca2+ extraction cannot be attributed to a residual irreversible effect of a previous Ca2+ load. The similarity of dehydration-induced rehydration rates of Ca2+-free cells in high-Na (Figure 3B) and high-K (Figure 3C) media suggests that the Pcat-mediated permeability for these 2 cations is similar. Microscopic observation on timed samples of profoundly dehydrated RBCs incubated in culture media at 37°C after ionophore and Ca2+ extraction showed slow and uneven rehydration, with many initially crenated RBCs regaining biconcave or spheroidal shapes.40 In all these experiments, rehydration occurred in the absence of contaminant white cells and platelets.

In the experiments of Figure 3E-H, the RBCs were suspended in 90K-SCN medium, which prevented their dehydration following Ca2+ loads (Figure 3E-G) or valinomycin treatment (Figure 3H). All Ca2+-loaded RBCs showed a hydration response that was not significantly modified by charybdotoxin (Figure 3F) or ouabain (Figure 3G), indicating that inhibition of Gardos channels or Na pumps had minimal effects on this response. On the other hand, the valinomycin-treated RBCs showed a barely detectable hydration response (Figure 3H). The results in Figure 3E-H thus show that Pcat can be activated by increased [Ca2+]i alone, without dehydration, and that K+ permeabilization itself has no effect on Pcat. In the conditions of Figure 3A, rehydration started with the cells initially profoundly dehydrated. When cells dehydrate by the net loss of KCl, the concentration of Cl− in the isotonic effluent (about 150 mM) is higher than in the cells (about 100 mM). The resulting dilution of the intracellular Cl− concentration increases the [Cl−]o/[Cl−]i ratio, and the anion exchanger rapidly restores the equality [Cl]o/[Cl]i = [H+]i/[H+]o with consequent intracellular acidification.41,42 In addition, the increase in impermeant anion concentration in the dehydrated RBCs hyperpolarizes the cells.41,43 Therefore, rehydration in the conditions of Figure 3A starts with the cells dehydrated, acidified, and hyperpolarized. On the other hand, in the initial conditions of Figure 3E, cell volume, pH, and membrane potential were all at physiological levels at the start of hydration. Because hydration proceeded comparably in both conditions, Ca2+ activation of Pcat appears not to be much affected by dehydration, pH, or membrane potential, although subtle effects cannot be ruled out from these data.

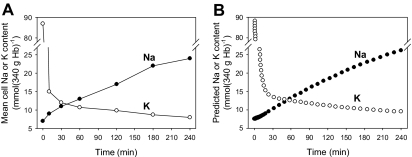

The measured changes in mean RBC Na+ and K+ contents during the dehydration-rehydration protocol of Figure 3A are shown in Figure 4A. The RBC K+ content fell sharply in the first 10 minutes and leveled off by 90 minutes, whereas the rate of Na+ gain was fairly constant throughout rehydration. These are average values for the RBC population as a whole and do not reflect the heterogeneity of the response, clearly discernible from the changing slope of the right-shifting osmotic fragility curves during rehydration (Figure 3A). From the data in Figure 4A it is possible to obtain a rough estimate of the mean value of the Na+ permeability, PNa, through Pcat, an important parameter for comparison with other permeation pathways in the RBC. Computation of the mean PNa through Pcat can be done by simulating the experimental conditions with a model of proven reliability and by searching for the PNa-Pcat values that would fit best the experimental data in Figure 4A. The computations were performed with the Lew–Bookchin model,41,43 and the results are shown in Figure 4B. The PNa-Pcat value required to generate the agreement apparent in the comparison of Figure 4A and B was 0.015 h−1, a relatively minor 10-fold increase in the normally low electrodiffusional component of the RBC Na+ permeability, a value 3 orders of magnitude lower than the electrodiffusional K+ permeability through Ca2+-saturated Gardos channels25,41,42,44,45 and within the same order of magnitude as the cation permeability generated by the interaction between Hb S polymers and the membrane of sickle RBCs, “Psickle” (reviewed by Lew and Bookchin33).

Figure 4.

Comparison of observed and model-simulated changes in the mean Na+ and K+ content of RBCs during the dehydration-rehydration protocol. RBCs were treated as described for Figure 1A and sampled for their Na+ and K+ contents, measured by flame photometry (see “Materials and methods”). (B) The Lew-Bookchin red cell model41 was used to simulate the sequence followed in the experiment of Figure 3A to estimate the required changes in Na+ and K+ permeabilities (PNa, PK) that would reproduce the extents and time course of the measured mean Na+ and K+ content changes in panel A. The PNa and PK values used for the fit shown were 0.015 h−1 (PNa through Pcat, a 10-fold increase over the normal mean electrodiffusional component of the Na+ permeability of about 0.0015 h−1 41,43) and 10 h−1 (PK through Gardos channels), respectively. The electrodiffusional anion permeability was set at 50 h−1 to represent the effect of 10 mM SCN−.42

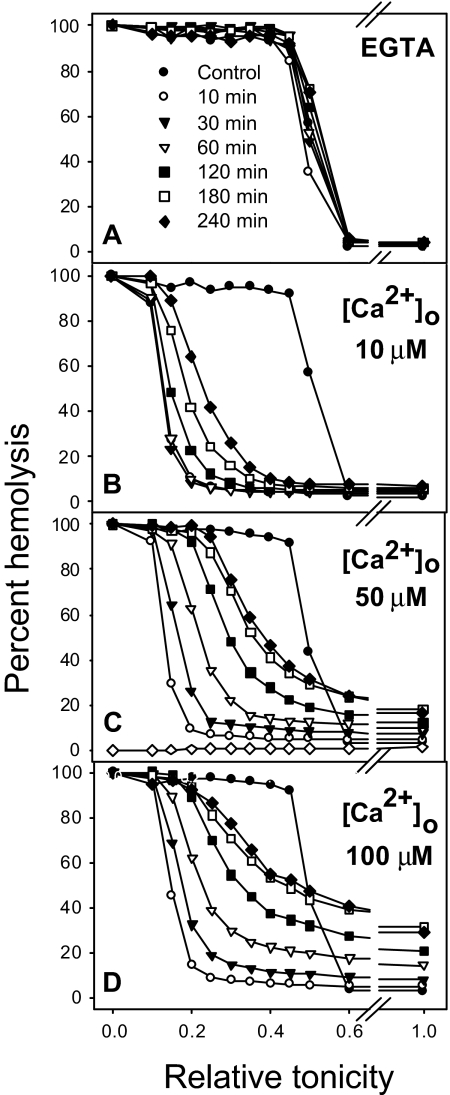

The experiment of Figure 5 shows the effect of increasing Ca2+ concentrations on the rehydration response. Figure 5A shows the volume distribution of ionophore A23187-treated RBCs in media with EGTA and no added Ca2+ and therefore no activation of Gardos channels. It can be seen that when [Ca2+]i is not elevated there is a barely detectable right shift of the osmotic fragility curves with time. Increasing Ca2+ concentrations triggered increasing rehydration responses (Figure 5B-D) reflecting higher levels of Pcat activation. The range of [Ca2+]i values over which Pcat activation increases in all the RBCs was far above physiological [Ca2+]i levels; at the [Ca2+]s levels of 50 μM used in most of the experiments reported here, the Pcat response was below its maximal Ca2+-saturated value.

Figure 5.

Effect of Ca2+ on the magnitude of the rehydration response. Experimental conditions were the same as in Figure 3A except that the total Ca2+ concentrations in the cell suspension were those indicated in panels B to D. Ionophore addition to 5% Hct RBC suspensions when the [Ca2+]s was higher than 100 μM was followed by rapid and extensive RBC lysis, unrelated to slow Pcat-mediated hydration, thus precluding investigation of Pcat at higher Ca2+ levels. In panel A the medium contained 50 μM Na-EGTA and no added calcium in order to chelate contaminant [Ca2+]o (less than 10 μM) and ensure [Ca2+]i levels below Gardos channel activation.

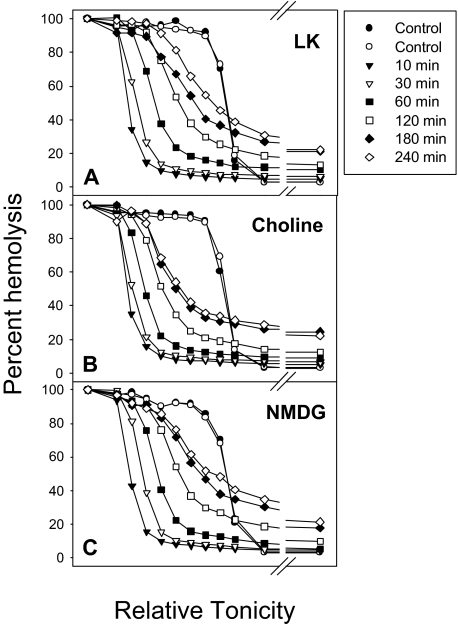

The cation selectivity of Pcat was investigated by isosmotic replacement of NaCl (Figure 6A, LK) with choline chloride (Figure 6B, choline) or with N-methyl-D-glucamine chloride (NMDG) (Figure 6C). Rehydration occurred in all conditions, indicating that choline and NMDG were permeable through Pcat. In 1 experiment we investigated the Mg2+ permeability through Pcat. After Ca2+ loading, the ionophore A23187 was extracted with albumin at 4°C and the RBCs resuspended in iso-osmotic MgCl2 with 10 mM NaSCN and 1 mM vanadate to inhibit the PMCA and retain the Ca2+ load. The results showed an almost identical rehydration pattern as that of Figure 6C, indicating that Pcat is permeable to Mg2+. These results suggest that Pcat has a wide ionophoric path in the open state with poor cation selectivity.

Figure 6.

The effect of isotonic replacement of Na+ by choline or N-methyl-D-glucamine (NMDG) on Ca2+-elicited rehydration. The experimental protocol was the same as that of Figure 3A, except that 140 mM NaCl in the suspending media was replaced by 140 mM choline chloride in panel B and by 140 mM NMDG chloride in panel C.

Discussion

The present results demonstrate that the activity of the plasma membrane Ca2+ pump declines monotonically with RBC age, that the subpopulation of high-Na+“calres” RBCs represents old RBCs near the end of their circulatory life span, and that RBCs have a poorly selective cation permeability pathway, Pcat, activated primarily by elevated [Ca2+]i. These results have important implications for understanding the changes in RBCs during physiological senescence and also for the interpretation of the statistical distributions of some classic RBC indices widely used in clinical laboratory tests.

The mechanism of programmed RBC senescence has been the subject of intense research for a few decades.46 Experimental evidence strongly supports terminal macrophage recognition and removal of RBCs following well-characterized antigenic changes in outer surface protein domains.47–53 There is also abundant evidence of gradual age-related RBC changes, including reduced enzymic activities,54–56 cross-linking of cytoskeletal components,57,58 cumulative oxidative damage,59,60 and loss of lipid asymmetry.61,62

The generally increasing density of aging RBCs has long been recognized,46,63–66 and density fractionation has been used extensively to separate age cohorts. Yet the mechanism of densification has seldom been addressed, and little is known about the composition of aging RBCs. The condition documented here for the high-Hb A1c calres RBCs is one of increased Na+ permeability, not the often-suggested terminal condition of profoundly dehydrated RBCs.46,67 The present findings of a monotonic decline in PMCA activity with RBC age and of the advanced age of calres RBCs suggest a working hypothesis for the mechanism of the homeostatic changes in aging RBCs: the decline in PMCA activity would drive the pump-leak Ca2+ balance toward higher [Ca2+]i levels, which when exceeding the threshold activation of Gardos channels would induce a gradual net loss of KCl and water, leading to progressive RBC densification. With PMCA Vmax variations of, for example, 60 and 2 mmol(340 g Hb)−1h−1,1 estimated pump-leak steady-state [Ca2+]i levels may vary from about 15 to 80 nM in young and old RBCs, respectively, leading to low-level Gardos channel activation in aging RBCs.45,68,69 Toward the final days in the circulation, the progressively increased [Ca2+]i levels, together with RBC dehydration, would activate Pcat, allowing the influx of Na+ at a rate exceeding the balancing capacity of the Na pump, eventually leading to net NaCl gain in excess of KCl loss and osmotic cell swelling toward a low-density terminal state (similar to the density of reticulocytes).16 Valres and calres RBCs, with elevated Na+ contents, were originally detected in density-fractionated samples of sickle cell anemia and normal blood, sharing the same light-density fraction as reticulocytes16 of 1.070 to 1.090 g/mL. This is well beyond the prelytic density range of 1.050 to 1.060 g/mL, suggesting that intravascular lysis may not play a significant role in the normal circulatory removal of RBCs. However, the actual density spread of circulating calres RBCs deserves further investigation.

Elevated [Ca2+]i was shown to be a much more powerful activator of Pcat than RBC dehydration, which, without elevated [Ca2+]i, was only a weak stimulus of Pcat. Permeation of very large cations such as NMDG (Figure 6) suggests that Pcat presents a large-conductance, wide ionophoric path in the open state. At uniformly high Ca2+ loads, Pcat was activated in all the RBCs of each blood sample but to different extents, with a unimodal pattern of variation. This variation was not age-related for the bulk of the RBC population, but the precision limits of the measurements did not exclude enhanced Pcat sensitivity in up to 5% to 6% of RBCs. Pcat activation was observed in the absence of contaminant white cells or platelets and is therefore strictly a RBC response. Although Pcat has all the attributes required to explain the density reversal process leading to calres-valres cell formation, there is no conclusive evidence for its activation in vivo. The conditions that activate Pcat experimentally, elevated [Ca2+]i and RBC dehydration, do occur in vivo to an extent that would appear sufficient to elicit a very slow net sodium gain and density reversal, with the oldest RBCs reaching a light terminal density similar to that of reticulocytes.

Finally, let us consider the implications of RBC densification with age to the statistical distribution of the hemoglobin concentration (HC) in normal RBCs. The distributions of Hb contents (CH) and volumes (V) of human RBCs have coefficients of variation of about 13%.34,70,71 If these 2 distributions were independent, the coefficient of variation (CV) of the HC, representing the ratio of Hb content to volume in each RBC, would be much larger than 13%. But the measured CV of the HC is only about 7%, indicating the biologic priority of uniformity of HC during RBC production. The measured CH distribution probably changes little after RBC release from the bone marrow, with perhaps minor Hb loss by exovesiculation.12 On the other hand, the measured V distribution is a composite of its original distribution at birth and its progressive reduction as the RBCs become increasingly dense with age. Therefore, the V and HC distributions of day-1 RBC cohorts must be much narrower than those measured for the whole RBC population comprising about 120 different day cohorts. This conclusion is supported by early flow cytometric measurements of HC distributions on density-separated RBCs,34 in which the CV of each one of 8 density fractions was about 3% (Table 2, column 234). Because each fraction represented a roughly 15-day age cohort, this result suggests that the coefficient of variation of the HC distribution of RBCs released from the bone marrow must be much less than 3%, an amazing degree of uniformity for a process delivering 10 billion RBCs per hour to a healthy adult's circulation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Wellcome Trust (United Kingdom), Medical Research Council (MRC) (United Kingdom), and National Institutes of Health (HL28018, HL58512, and RR12248).

We thank Lynn Macdonald for excellent technical assistance and Angus Gidman for the supervision of the Hb A1c measurements in Cambridge (Biochemistry Laboratory, Addenbrooke's Hospital, Cambridge, United Kingdom; project 719). We are grateful to Hans U. Lutz and Poul Bennekou for reading early drafts of the manuscript and for helpful discussions and suggestions.

Footnotes

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: V.L.L. designed the experiments, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript; N.D. and Z.E. performed experiments and contributed to data analysis; A.M. and L.V. performed experiments; T.T. contributed to data analysis and manuscript revision; and R.M.B. contributed to the experimental design, data analysis, and manuscript revision.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: V. L. Lew, Department of Physiology, Development and Neuroscience, University of Cambridge, Downing Street, Cambridge CB2 3EG, United Kingdom; e-mail: vll1@cam.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Lew VL, Daw N, Perdomo D, et al. Distribution of plasma membrane Ca2+ pump activity in normal human red blood cells. Blood. 2003;102:4206–4213. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-06-1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schatzmann HJ. ATP-dependent Ca++-extrusion from human red cells. Experientia. 1966;22:364–365. doi: 10.1007/BF01901136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schatzmann HJ. The red cell calcium pump. Annu Rev Physiol. 1983;45:303–312. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.45.030183.001511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carafoli E, Stauffer T. The plasma membrane calcium pump: functional domains, regulation of the activity, and tissue specificity of isoform expression. J Neurobiol. 1994;25:312–324. doi: 10.1002/neu.480250311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang KKW, Villalobo A, Roufogalis BD. The plasma membrane calcium pump: a multiregulated transporter. Trends Cell Biol. 1992;2:46–52. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(92)90162-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferreira HG, Lew VL. Use of ionophore A23187 to measure cytoplasmic Ca buffering and activation of the Ca pump by internal Ca. Nature. 1976;259:47–49. doi: 10.1038/259047a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lew VL, Tsien RY, Miner C, Bookchin RM. Physiological [Ca2+]i level and pump-leak turnover in intact red cells measured using an incorporated Ca chelator. Nature. 1982;298:478–481. doi: 10.1038/298478a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vincenzi FF, Hinds TR. Decreased Ca pump ATPase activity associated with increased density in human red blood cells. Blood Cells. 1988;14:139–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luthra MG, Kim HD. (Ca2+ + Mg2+)-ATPase of density-separated human red cells. Effects of calcium and a soluble cytoplasmic activator (calmodulin). Biochim Biophys Acta. 1980;600:480–488. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(80)90450-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Romero PJ, Romero EA. Differences in Ca2+ pumping activity between sub-populations of human red cells. Cell Calcium. 1997;21:353–358. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(97)90028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bookchin RM, Gallop PM. Structure of hemoglobin A1c: nature of the N-terminal chain blocking group. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1968;32:86–93. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(68)90430-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bosch FH, Werre JM, Roerdinkholder-Stoelwinder B, et al. Characteristics of red blood cell populations fractionated with a combination of counterflow centrifugation and Percoll separation. Blood. 1992;79:254–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bunn HF, Haney DN, Gabbay KH, Gallop PM. Further identification of the nature and linkage of the carbohydrate in hemoglobin A1c. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1975;67:103–109. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(75)90289-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bunn HF, Haney DN, Kamin S, Gabbay KH, Gallop PM. The biosynthesis of human hemoglobin A1c. Slow glycosylation of hemoglobin in vivo. J Clin Invest. 1976;57:1652–1659. doi: 10.1172/JCI108436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haney DN, Bunn HF. Glycosylation of hemoglobin in vitro: affinity labeling of hemoglobin by glucose-6-phosphate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1976;73:3534–3538. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.10.3534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bookchin RM, Etzion Z, Sorette M, et al. Identification and characterization of a newly recognized population of high-Na+, low-K+, low-density sickle and normal red cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:8045–8050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.130198797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crespo LM, Novak TS, Freedman JC. Calcium, cell shrinkage, and prolytic state of human red blood cells. Am J Physiol. 1987;252:C138–C152. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1987.252.2.C138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ponder E. The prolytic loss of K from human red cells. J Gen Physiol. 1947;30:235–246. doi: 10.1085/jgp.30.3.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ponder E. New York, NY: Grune & Stratton; 1948. Hemolysis and Related Phenomena. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parker JC. Hemolytic action of potassium salts on dog red blood cells. Am J Physiol. 1983;244:C313–C317. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1983.244.5.C313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tiffert T, Daw N, Perdomo D, Lew VL. A fast and simple screening test to search for specific inhibitors of the plasma membrane calcium pump. J Lab Clin Med. 2001;137:199–207. doi: 10.1067/mlc.2001.113112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.García-Sancho J, Lew VL. Detection and separation of human red cells with different calcium contents following uniform calcium permeabilization. J Physiol. 1988;407:505–522. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Payne JA, Lytle C, McManus TJ. Foreign anion substitution for chloride in human red blood cells: effect on ionic and osmotic equilibria. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:C819–C827. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.259.5.C819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gardos G. The function of calcium in the potassium permeability of human erythrocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1958;30:653–654. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(58)90124-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lew VL, Ferreira HG. Calcium transport and the properties of a calcium-activated potassium channel in red cell membranes. In: Kleinzeller A, Bronner F, editors. Current Topics in Membranes and Transport. Vol 10. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1978. pp. 217–277. [Google Scholar]

- 26.García-Sancho J, Lew VL. Detection and separation of human red cells with different calcium contents following uniform calcium permeabilization. J Physiol. 1988;407:505–522. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pereira AC, Samellas D, Tiffert T, Lew VL. Inhibition of the calcium pump by high cytosolic Ca2+ in intact human red cells. J Physiol. 1993;461:63–73. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grygorczyk R. Temperature dependence of Ca2+-activated K+ currents in the membrane of human erythrocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1987;902:159–168. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(87)90291-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abraham EC, Abraham A, Stallings M. High-pressure liquid chromatographic separation of glycosylated and acetylated minor hemoglobins in newborn infants and in patients with sickle cell disease. J Lab Clin Med. 1984;104:1027–1034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dagher G, Lew VL. Maximal calcium extrusion capacity and stoichiometry of the human red cell calcium pump. J Physiol. 1988;407:569–586. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holtzclaw JD, Jiang M, Yasin Z, Joiner CH, Franco RS. Rehydration of high-density sickle erythrocytes in vitro. Blood. 2002;100:3017–3025. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-02-0631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Franco RS, Lohmann J, Silberstein EB, et al. Time-dependent changes in the density and hemoglobin F content of biotin-labeled sickle cells. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:2730–2740. doi: 10.1172/JCI2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lew VL, Bookchin RM. Ion transport pathology in the mechanism of sickle cell dehydration. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:179–200. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00052.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lew VL, Raftos JE, Sorette MP, Bookchin RM, Mohandas N. Generation of normal human red cell volume, hemoglobin content and membrane area distributions, by “birth” or regulation. Blood. 1995;86:334–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raftos JE, Bookchin RM, Lew VL. Distribution of chloride permeabilities in normal human red cells. J Physiol. 1996;491:773–777. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barksmann TL, Kristensen BI, Christophersen P, Bennekou P. Pharmacology of the human red cell voltage-dependent cation channel; part I. Activation by clotrimazole and analogues. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2004;32:384–388. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2004.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bennekou P, Barksmann TL, Kristensen BI, Jensen LR, Christophersen P. Pharmacology of the human red cell voltage-dependent cation channel. Part II: inactivation and blocking. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2004;33:356–361. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bennekou P, Barksmann TL, Christophersen P, Kristensen BI. The human red cell voltage-dependent cation channel. Part III: distribution, homogeneity and pH dependence. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2006;36:10–14. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bennekou P, Barksmann TL, Jensen LR, Kristensen BI, Christophersen P. Voltage activation and hysteresis of the non-selective voltage-dependent channel in the intact human red cell. Bioelectrochemistry. 2004;62:181–185. doi: 10.1016/j.bioelechem.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tiffert T, Lew VL, Ginsburg H, et al. The hydration state of human red blood cells and their susceptibility to invasion by Plasmodium falciparum. Blood. 2005;105:4853–4860. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lew VL, Bookchin RM. Volume, pH and-ion content regulation in human red cells: analysis of transient behavior with an integrated model. J Membr Biol. 1986;92:57–74. doi: 10.1007/BF01869016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Freeman CJ, Bookchin RM, Ortiz OE, Lew VL. K-permeabilized human red cells lose an alkaline, hypertonic fluid containing excess K over diffusible anions. J Membr Biol. 1987;96:235–241. doi: 10.1007/BF01869305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lew VL, Freeman CJ, Ortiz OE, Bookchin RM. A mathematical model on the volume, pH and ion content regulation of reticulocytes. Application to the pathophysiology of sickle cell dehydration. J Clin Invest. 1991;87:100–112. doi: 10.1172/JCI114958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lew VL, Ferreira HG. Variable Ca sensitivity of a K-selective channel in intact red-cell membranes. Nature. 1976;263:336–338. doi: 10.1038/263336a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Simons TJB. Calcium-dependent potassium exchange in human red cell ghosts. J Physiol. 1976;256:227–244. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1976.sp011322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Clark MR. Senescence of red blood cells: progress and problems. Physiol Rev. 1988;68:503–554. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1988.68.2.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lutz HU, Bussolino F, Flepp R, et al. Naturally occurring anti-band-3 antibodies and complement together mediate phagocytosis of oxidatively stressed human erythrocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:7368–7372. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.21.7368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lutz HU, Gianora O, Nater M, Schweizer E, Stammler P. Naturally occurring anti-band 3 antibodies bind to protein rather than to carbohydrate on band 3. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:23562–23566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lutz HU, Stammler P, Kock D, Taylor RP. Opsonic potential of C3b-anti-band 3 complexes when generated on senescent and oxidatively stressed red cells or in fluid phase. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1991;307:367–376. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-5985-2_33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lutz HU. A cell-age specific antigen on senescent human red blood cells. Acta Biol Med Ger. 1981;40:393–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Arese P, Turrini F, Schwarzer E. Band 3/complement-mediated recognition and removal of normally senescent and pathological human erythrocytes. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2005;16:133–146. doi: 10.1159/000089839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Turrini F, Arese P, Yuan J, Low PS. Clustering of integral membrane proteins of the human erythrocyte membrane stimulates autologous IgG binding, complement deposition, and phagocytosis. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:23611–23617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lutz HU, Stammler P, Fasler S. Preferential formation of C3b-IgG complexes in vitro and in vivo from nascent C3b and naturally occurring anti-band 3 antibodies. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:17418–17426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Beutler E. How do red cell enzymes age? A new perspective. Br J Haematol. 1985;61:377–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1985.tb02841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Beutler E. Biphasic loss of red cell enzyme activity during in vivo aging. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1985;195:317–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Beutler E. The relationship of red cell enzymes to red cell life-span. Blood Cells. 1988;14:69–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lorand L, Weissmann LB, Epel DL, Bruner-Lorand J. Role of intrinsic transglutaminase in the Ca2+-mediated crosslinking of erythrocyte proteins. Biochemistry. 1976;75:4479–4481. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.12.4479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lorand L, Siefring GE, Jr, Lowe-Krentz L. Enzymatic basis of membrane stiffening in human erythrocytes. Semin Hematol. 1979;16:65–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brugnara C, De Franceschi L. Effect of cell age and phenylhydrazine on the cation transport properties of rabbit erythrocytes. J Cell Physiol. 1993;154:271–280. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041540209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.De Franceschi L, Olivieri O, Corrocher R. Erythrocyte aging in neurodegenerative disorders. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 2004;50:179–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kuypers FA. Phospholipid asymmetry in health and disease. Curr Opin Hematol. 1998;5:122–131. doi: 10.1097/00062752-199803000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kuypers FA, Lewis RA, Hua M, et al. Detection of altered membrane phospholipid asymmetry in subpopulations of human red blood cells using fluorescently labeled annexin V. Blood. 1996;87:1179–1187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Corash L. Density dependent red cell separation. In: Beutler E, editor. Red Cell Metabolism. New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone; 1986. pp. 90–107. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lutz HU. Red cell density and red cell age. Blood Cells. 1988;14:76–80. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Christian JA, Wang J, Kiyatkina N, Rettig M, Low PS. How old are dense red blood cells? The dog's tale. Blood. 1998;92:2590–2591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lutz HU, Stammler P, Fasler S, Ingold M, Fehr J. Density separation of human red blood cells on self forming Percoll gradients: correlation with cell age. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1116:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(92)90120-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Romero PJ, Romero EA. The role of calcium metabolism in human red blood cell ageing: a proposal. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 1999;25:9–19. doi: 10.1006/bcmd.1999.0222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Porzig H. Comparative study of the effects of propanolol and tetracaine on cation movements in resealed human red cell ghosts. J Physiol. 1975;249:27–50. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1975.sp011001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Grygorczyk R, Schwarz W. Properties of the Ca2+-activated K+ conductance of human red cells as revealed by the patch-clamp technique. Cell Calcium. 1983;4:499–510. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(83)90025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gifford SC, Derganc J, Shevkoplyas SS, Yoshida T, Bitensky MW. A detailed study of time-dependent changes in human red blood cells: from reticulocyte maturation to erythrocyte senescence. Br J Haematol. 2006;135:395–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Canham PB, Burton AC. Distribution of size and shape in populations of normal human red cells. Circ Res. 1968;22:405–422. doi: 10.1161/01.res.22.3.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]