Abstract

Objectives To determine what paediatric specialist registrars think of the educational supervision they have received and what advice they would give to a consultant who wanted to be a more effective educational supervisor.

Design A questionnaire study.

Setting The North Thames Deanery, UK.

Participants 129 year 3, 4 or 5 paediatric specialist registrars in the North Thames Deanery.

Main outcome measures Reported value of educational supervision on a Likert scale; what elements of educational supervision were reported to be most useful; what elements of educational supervision were reported to be done poorly; what advice would specialist registrars give to a consultant who wanted to be a more effective educational supervisor.

Results 86/129 specialist registrars responded (67%). The mean score on the Likert scale (0-a complete waste of time; 100-excellent) was 57 with 37% of respondents giving a score of less than 50. The most valued aspects of educational supervision were: feedback on performance—cited by 50 respondents (56% of respondents); career advice—cited by 43 (48%); objective setting—cited by 36 (40%); pastoral support—cited by 25 (28%). Aspects of educational supervision that were reported to be often not done well were: commitment to educational supervision—cited by 44 respondents (49% of respondents); ensuring sessions are bleep-free—cited by 43 (48%); listening rather than talking—cited by 23 (26%); being encouraging—cited by 18 (20%). Advice to consultants about how to improve educational supervision included: listen rather than talk; be encouraging; treat the trainee as an individual with individual needs.

Conclusions We can find no other study of trainees' views about how educational supervision can be improved. Although some trainees found educational supervision very valuable, many did not. Educational supervision should only be carried out by consultants who are committed to the task. An educational supervisor should listen carefully in order to understand the trainee's individual ambitions and needs, should provide specific feedback on performance and should be encouraging.

INTRODUCTION

We use the term ‘educational supervision’ to describe the process (largely involving regular appraisal interviews) whereby a more senior doctor helps a trainee to maximize the benefit that the trainee gets from a training position in order to fulfil his/her long term career aims.1 A senior doctor can help a trainee identify worthwhile local educational opportunities, can supply feedback on the trainee's progress and can provide practical support and encouragement. An enthusiast has described the educational supervisor as ‘perhaps the most crucial figure in ensuring the effectiveness of postgraduate medical training.’2

Doctors in training were rarely offered educational supervision before the 1990s. However, educational supervision became a mandatory part of the training of specialist registrars in the UK in the mid 1990s3 and continues to be viewed as a central part of the training of all doctors in the UK.4 We have, however, noticed that both trainees and consultants often regard educational supervision as being an unwelcome and bureaucratic requirement rather than as being a useful process.

Our study had two aims:

To determine how useful paediatric specialist registrars found educational supervision to be;

To obtain the views of paediatric specialist registrars about ways to improve the process of educational supervision.

We used a questionnaire to determine the views of a group of experienced paediatric specialist registrars in the North Thames region in the UK. We have been unable to find any other study which has sought the views of trainees about how the process of educational supervision can be improved.

METHODS

After a pilot survey involving seven specialist registrars known to us, in July 2005 we sent a questionnaire to each of the 129 paediatric specialist registrars in the North Thames area who were in year three, four or five of their five year training programme. In order to preserve anonymity, there were no marks or numbers on the questionnaires. We sent two reminders via email over the following three weeks.

The preprinted options for responding to questions two and three (see below) represented common responses obtained from a previous similar survey we carried out in 1999 (unpublished data).

The questionnaire

-

‘Please rate the educational supervision you have received in the last year by placing a cross on the most appropriate part of this line.’

There was a Likert scale ranging from 0 (‘complete waste of time’) to 100 (‘excellent’).

-

‘Please tick the aspects of educational supervision you have found most helpful.’

There were boxes to tick next to the following four options: ‘Objective Setting’, ‘Career Advice’, ‘Pastoral Support’ and ‘Feedback on Performance’. There was also a large space with the prompt ‘Others—please specify’ for the specialist registrars to record further responses to this question.

-

‘In your experience which of the following aspects of the way Educational Supervision is carried out are sometimes not done very well by consultants.’

There were boxes to tick next to the following four options: ‘Being encouraging’, ‘Ensuring sessions are bleep free’, ‘Listening rather than talking’ and ‘Commitment to educational supervision’. There was also a large space with the prompt ‘Others—please specify’ for the specialist registrars to record further responses to this question.

‘What advice would you give to a consultant to help him/her to be a more effective educational supervisor?’ There was space for considerable amounts of free text.

RESULTS

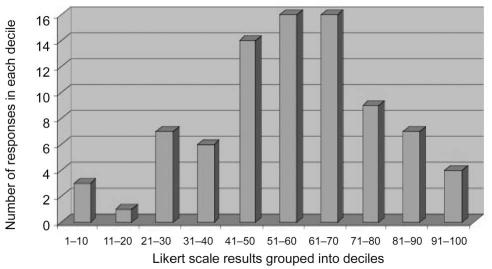

86 out of 129 specialist registrars responded (67%). According to the ratings provided on the Likert scale, the respondents' opinions of the value of the educational supervision that they had received ranged over the entire scale between 0 (‘complete waste of time’) and 100 (‘excellent’) (Figure 1). The mean score was 57. Only ten respondents (11%) gave a score of more than 80. Thirty-two respondents (37%) gave a score of less than 50.

Figure 1.

Numbers of responses (expressed as deciles) to the request to rate the value of educational supervision on a Likert scale ranging from 0 (‘a complete waste of time’) to 100 (‘excellent’)

What did the respondents find most helpful in educational supervision?

The numbers of the 89 respondents who ticked the boxes alongside the four preprinted suggestions were as follows:

Feedback on performance: 50 (56%);

Career advice: 43 (48%);

Objective setting: 36 (40%);

Pastoral support: 25 (28%).

There were relatively few free text comments and only one idea was cited as being helpful by more than two respondents—non-clinical advice (cited by five respondents). Examples of such non-clinical advice included getting an article published, interview skills and advice on CV presentation and job applications.

What did the respondents report was not done well by educational supervisors?

The numbers (percentages) of the 89 respondents who ticked the boxes alongside the four preprinted suggestions were as follows:

Commitment to educational supervision: 44 (49%);

Ensuring sessions are bleep-free: 43 (48%);

Listening rather than talking: 23 (26%);

Being encouraging: 18 (20%).

Ideas expressed by more than two respondents via free text comments were (in order):

Educational supervision is often merely a form-filling exercise unless there are problems (5 respondents);

Difficulty in arranging appointments-feel bad bothering consultants (4 respondents);

Not enough time per session (3 respondents);

Consultants not straight enough with constructive feedback (3 respondents);

Little/no action taken by consultant in response to points raised by trainee (3 respondents).

Two respondents complained that consultants seemed unsympathetic to life stresses outside work. Two other respondents complained that the consultants seemed uninterested in educational supervision.

What advice was offered to consultants wanting to improve their educational supervision?

This was the question that provoked the most responses in the form of free text, summarized in Box 1. Box 2 lists some direct quotes from trainees in response to this question, and in response to the other three questions in our questionnaire.

DISCUSSION

We found that, although most trainees had found educational supervision to be at least somewhat useful, more than a third of trainees rated the educational supervision they had received as being closer to ‘a complete waste of time’ than to ‘excellent’. An important problem was the perceived lack of commitment by individual educational supervisors.

The most important elements of educational supervision were considered to be the provision of constructive feedback, career advice and help with setting objectives. Suggestions about how to improve educational supervision included recognizing the importance of: listening rather than talking; treating the trainee as someone with individual needs; being encouraging.

Strengths of our study included the fact that we surveyed all the year 3-5 paediatric specialist registrars in a defined geographic area. Our questions were few and simple. We emphasized that participation in the survey was anonymous. We believe that this anonymity encouraged respondents to tell the truth about their feelings and experiences.

We were unable to find any comparable studies and therefore designed our own questionnaire. Our choice of the specific aspects of educational supervision that we investigated was informed by the results of a previous similar, unpublished, survey which was carried out by one of us (BL) in 1999. Our questionnaire encouraged our respondents to write free text, which they did (Boxes 1 and 2).

Shortcomings of our study include the fact that the study was relatively small and concerned trainees in one area of the UK. We consider that the response rate of 67% was reasonable for a study of this kind and was lower than it would otherwise have been because the steps we took to ensure anonymity precluded us sending specific reminders to non-responders. It seems unlikely that enthusiasts for educational supervision were over-represented among the non-responders.

Box 1 Advice offered to a hypothetical consultant wanting to be a more effective educational supervisor (number of respondents citing this advice)

Give objective, constructive criticism and feedback on performance (10)

Listen (9)

Give guidance in objective setting (9)

Understand the individual needs of the trainee (7)

Be encouraging (7)

Meet regularly and set specific time periods to re-assess and review objectives (6)

Provide career advice—take a real interest in trainee's career (5)

Be supportive (4)

Be sympathetic (3)

Be up to date with Royal College Syllabus and available courses (3)

Allow set time for appointments (3)

Ask about the trainee's personal life (2)

Ensure the confidentiality of the discussions (2)

There have been many other surveys of trainees' opinions of their training.5 However, we have been able to find just two studies that have specifically concerned trainees' views of their educational supervision.6,7

One of these studies was of 21 specialist registrars (and 43 consultants) in occupational medicine in the Armed Forces.6 The authors reported that the trainees and consultants were in broad agreement about the purpose and most important elements of educational supervision: ‘monitor SpR progress, support to SpR and identify SpR problems.’ The other study, of 103 senior house officers in psychiatry, rated ‘regular appraisal and assessment of skills and deficits as the most important role of the educational supervisor.’7 Neither of these two studies was as detailed about the practicalities of educational supervision as our study was and neither study investigated how the trainees thought that the process could be improved.

Box 2 Some quotes from trainees about educational supervision

‘Talk constructively about the trainee, not about yourself, your own career or internal politics.’

‘Not all consultants have the “gift”—don't force others, they'll end up doing it badly.’

‘Take it seriously.’

‘Go and get some training!!’

‘Some consultants are totally unaware of what is required and see the process as a form-filling exercise, forced upon them, an inconvenience.’

‘I think the formal form-filling is seen as a waste of time by some or an opportunity to assert power by others.’

‘Some educational supervisors are not at all committed, too busy, you feel bad bothering them.’

‘As far as being encouraging, I think this is one of the least well carried out tasks by consultants because no one was ever encouraging to them.’

‘Ask to see my portfolio so I can at least think you're vaguely interested.’

‘I think you genuinely need to be interested in educational supervision. When supervisors are, it is often useful, when they are not, it is usually completely useless!’

‘When done well, educational supervision is motivating and inspiring. When done badly it is the opposite.’

In our study, advice for improving educational supervision was provided by trainees working in just one part of the UK. Nevertheless, it is our view that their advice may prove useful for trainers working in other specialities and in other places. The trainees in our study were relatively senior. Thus not all our findings are likely to be generalizable to more junior trainees.

We consider that there can be few educational supervisors who would not be interested in Boxes 1 and 2. We were struck by the observation that one of the most commonly cited pieces of advice to consultants was to listen, given the central role of listening in most consultants' view of how medicine should be practiced.

An important conclusion that could be drawn from our study by postgraduate deans and others involved in organizing training programs is that only consultants committed to the task of educational supervision should carry it out. As one trainee succinctly put it ‘When done well, educational supervision is motivating and inspiring. When done badly it is the opposite.’

Competing interests None declared.

Funding None.

Ethical approval None.

Guarantor BL.

Contributorship BL had the idea for this research. BL and DB designed the questionnaire and analysed the data. BL wrote the paper.

Acknowledgments We are grateful to Keith McKay and staff at the North Thames Deanery for sending out the questionnaires and electronic reminders.

References

- 1.Lloyd BW. How to be an effective educational supervisor. Br J Hosp Med 1996:56; 585-7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coles C. The educational supervisor's role in medicine. In: Peyton JWR (ed). Teaching and Learning in Medical Practice. Rickmansworth: Manticore Europe Limited, 1998.

- 3.Department of Health. A Guide to Specialist Registrar Training. London: DoH, 1998

- 4.The Four UK Health Departments. Modernising Medical Careers: the Next Steps. The Future Shape of Foundation, Specialist and General Practice Training Programmes. London: DoH, 2004

- 5.Paice E, Aitken M, Cowan G, Heard S. Trainee Satisfaction before and after the Calman reforms of specialist training: questionnaire study. BMJ 2000;320: 832-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Owen JP. A survey of the provision of educational supervision in occupational medicine in the Armed Forces. Occupat Med 2005;55: 227-33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Day E, Brown N. The role of the educational supervisor. Psychiatr Bull 2000;24: 216-8 [Google Scholar]