Abstract

Mechanical stress is an important epigenetic factor for regulating skeletal remodeling, and application of force can lead to remodeling of both bone and cartilage. Chondrocytes, osteoblasts and osteoclasts all participate and interact with each other in this remodeling process. To study cellular responses to mechanical stimuli in a system that can be genetically manipulated, we used mouse midpalatal suture expansion in vivo. 6-weeks-old male C57BL/6 mice were subjected to palatal suture expansion by opening loops with an initial force of 0.56N for periods of 1, 3, 7, 14 or 28 days. Periosteal cells in expanding sutures showed increased proliferation, with Ki67 positive cells representing 1.8±0.1% to 4.5±0.4% of total suture cells in control groups and 12.0±2.6% to 19.9±1.2% in experimental/expansion groups (p<0.05). Starting at day 1, cells expressing alkaline phosphatase and type I collagen were seen. New cartilage and bone formation was observed at the oral edges of the palatal bones at day 7; at the nasal edges only bone formation without cartilage appeared to occur. An increase in osteoclast numbers suggested increased bone remodeling, ranging from 60 to 160% throughout the experimental period. Decreased Saffranin O staining after day 3 suggested decreased proteoglycan content in the secondary cartilage. MicroCT showed a significant increase in maxillary width at days 14 and 28 (from 2334±4μm to 2485±3μm at day 14 and from 2383±5μm to 2574±7μm at day 28, p<0.001). The suture width was increased at days 14 and 28, except in the oral third region at day 28 (from 48±5μm to 36±4μm, p<0.05). Bone volume/total volume was significantly reduced at days 14 and 28 (50.2±0.7% vs. 68.0±3.7% and 56.5±1.0%vs. 60.9±1.3%, respectively, p<0.05), indicative of increased bone marrow space. These findings demonstrate that expansion forces across the midpalatal suture promote bone resorption through activation of osteoclasts and bone and cartilage formation via increased proliferation and differentiation of periosteal cells. Mouse midpalatal suture expansion would be useful in further studies of the ability of mineralized tissues to respond to mechanical stimulation.

Keywords: suture, mechanical force, bone remodeling, chondrocyte, osteoblast

Introduction

The skeleton is a load bearing structure able to respond to a variety of genetic and epigenetic factors. One important epigenetic factor is the mechanical environment, the stresses and strains, to which skeletal cells are subjected. Chondrocytes, osteoblasts and osteoclasts are constantly exposed to physical forces that modulate the cellular phenotype and gene expression during development and postnatal growth. Mechanically induced cellular alterations are also major contributors to pathological conditions, such as osteoarthritis and osteoporosis [1]. The ability of bone and cartilage to respond to mechanical stress provides the foundation for many orthopedic and orthodontic procedures. Thus, studies of how mechanical forces influence skeletal structure and function shed light on basic bone cell biology and help improve strategies for treating skeletal diseases.

Recent studies of cultured osteoblasts or chondrocytes have shown that mechanical strain results in changes in gene expression. For example, application of strain to osteoblasts increases mRNA levels of Cox-2 (cyclooxygenase-2) and the immediate early gene c-fos within an hour [2], as well as the levels of extracellular matrix proteins osteopontin and osteocalcin within 24 hours [3]. In both proliferating and matrix-forming chondrocytes, cyclic mechanical strain can increase parathyroid-hormone-related protein mRNA levels [4]. Such in vitro studies are interesting, but it is difficult to extrapolate from culture conditions to the in vivo situation. In order to obtain insights into interactions among different types of cells as they respond to mechanical stimuli, it is crucial to utilize an in vivo animal model. Craniofacial sutures in rats and mice have been used for such biomechanical studies [5–7], but only limited information is available on the cellular and molecular events induced when such sutures are exposed to mechanical stress.

To obtain better insights into such cellular/molecular events, we have initiated studies of midpalatal suture expansion. The midpalatal suture, located between the maxillary bones in the palate, contains secondary cartilage that is highly responsive to various mechanical forces [8–10]. Midpalatal suture expansion, or rapid palatal expansion, has been used clinically for more than 40 years to correct maxillary width deficiencies [11]. The underlying mechanisms that drive bone formation during this process are largely unknown, but it has been reported that tensional force applied to the midpalatal suture of rats induces the replacement of cartilaginous tissues by bone [12]. Furthermore, it has been suggested that mesenchymal cells located on the inner side of the cartilaginous tissue proliferate and differentiate into osteoblasts when the suture is expanded [13]. It is highly desirable to perform suture expansion in mice since various strains of genetically manipulated mice can be compared to decipher underlying genetic response mechanisms. In this paper, we describe how an expansive force across the midpalatal suture of mice induces a process of suture remodeling and new bone formation that results in regeneration of the suture structure.

Materials and Methods

Experimental animals

A total of 60 male C57BL/6 mice, 6-week-old and 20–21g in weight, were used. Mice at this stage are in a growing phase and their first and second maxillary molars are fully erupted. For histological and microCT analysis, 48 animals were divided into 4 experimental groups that were treated with an applied expansion force for different time periods: 1, 3, 7 or14 days with twelve animals for each time point, including six with midpalatal suture expansion and six serving as controls (three non-operated and three sham operated). Six animals were studied at day 28, including three with midpalatal suture expansion and three serving as controls. In addition, six animals were used for fluorescence bone labeling studies with three for control and three for expansion. Animals were weighed at the beginning and the end of the experimental period. All animal work was performed using protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

Expansion procedure

The animals were anesthetized using a combination of ketamine (87mg/kg) and xylazine (13mg/kg) in PBS. Animals were placed on their backs in a custom-made restrainer. To apply a distracting force to the midpalatal suture, opening loops were made using 0.014 inch stainless steel orthodontic wire (GAC International Inc., Bohemia, NY). The appliances were bonded to first and second maxillary molars on both sides by a light cured adhesive (3M Unitek, Monrovia, CA) (Fig. 1A). For sham operation, dead opening loops with no expansion force were prepared and bonded to first and second maxillary molars.

Figure 1. Midpalatal suture expansion in mice.

(A) Occlusal view of 6-weeks-old mouse maxilla. Experimental/expansion maxilla with the opening loop bonded to the first and second molars (left) and non-operated control (right).

(B) The F/Δ diagram for the opening loop. Deformation was measured for 10 different loops at three force levels. Linear regression analysis was performed to create the trend line (R2=0.98). Since the force-deflection curve was measured at room temperature ex vivo, it is likely that force-deflection is different when the loop is placed in vivo.

To calibrate the amount of force produced by activation of the opening loop, the F/Δ rates of the appliance were determined. Ten appliances were activated at three force levels (measured by a Dontrix force gauge, GAC International Inc.) and the amount of deflection was determined by a digital caliper (Mitutoyo, Japan) (Fig. 1B). The initial force magnitude used in the experiments was 0.56N. The force gradually decreased during the experimental period mostly due to expansion of the midpalatal suture. The average force was about 0.28N at day 7 and 0.05N at day 14.

To characterize the pattern of suture expansion and palatal bone movement upon the application of opening loop, the suture width of control and experimental animals was measured (Fig. 3), and the degree by which the palatal bones rotated was calculated.

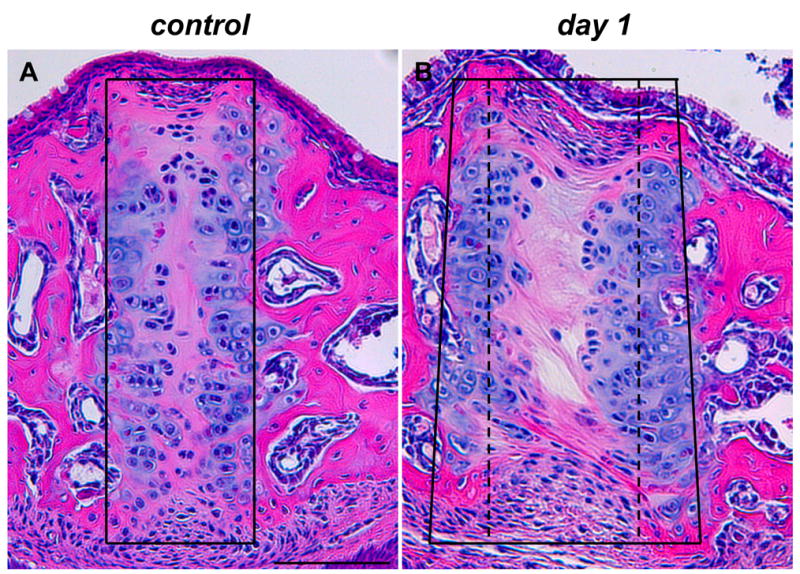

Figure 3. Changes of suture width in histological sections.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining of frontal sections of midpalatal sutures of control (A) and expansion (B) animals. In control sections, the suture area was contained within a rectangular frame (A); in expansion sections, the suture area was widened and contained within a trapezoidal frame (compare the control width indicated by a stippled line with the expanded width indicated by a solid line in B). The two images, as well as all subsequent images, are oriented with nasal side up and oral side down. Scale bar (A): 100μm.

Tissue processing

The maxillae including the midpalatal suture were dissected from all the control and experimental mice. For microCT evaluation, bilateral maxillary bones with the midpalatal suture were dissected at days 14 and 28 and fixed with 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde in 0.1M phosphate buffered saline solution before x-ray imaging. For histological analysis, immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization, specimens were dissected at days 1, 3, 7 and 14 and fixed overnight with the same solution. The fixed specimens were demineralized in 0.5M ethylenediaminetetra-acetic acid (EDTA) for 14 days at 4°C and then embedded in paraffin. For alkaline phosphatase (AP) and tartrate resistant acid phosphatase staining (TRAP), specimens were embedded in OCT (Tissue Tek, Miles Laboratories, Naperville, USA) for frozen sections instead of paraffin. Serial frontal sections between first and second molar levels were cut at 5μm and 8μm from paraffin embedded and OCT embedded frozen specimens, respectively.

Microcomputed tomography

Desktop μCT 40 system (Scanco Medical AG, Switzerland) was used for scanning as well as for morphometric analysis. The intact palate/maxillae were placed in a holder and scanned with the palate perpendicular to the image plane producing a 3D stack of images or volume. The scanned volume had a voxel resolution of 12 microns. These stacks of images were then passed through a 3D Gaussian filter (with mean = 1.2 and filter support = 1). 3D morphometric analysis was performed by selecting the palatal bone regions to obtain the Bone Volume Fraction (using global adaptive thresholding) [14]. The width of the palatal/maxillary bones was measured as the distance between alveolar bones at first molar level. The width of the suture was obtained by measuring the nasal third, middle third and oral third of the suture at the same level.

Fluorescence labeling and sample processing

Mice were given an intraperitoneal injection of alizarin complexone (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at 60mg/kg body weight on the day the opening loops were applied and calcein (Sigma) at 6mg/kg body weight on day 14. Control mice were given the fluorochrome dyes at the same time. Mice were sacrificed two days after the second dye injection, and the maxillae were harvested for analysis. The specimens were fixed with 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde and dehydrated in a series of graded alcohols before embedded in Osteo-Bed resin (Polysciences, Inc., Warrington, PA) following manufacturer’s instruction. Frontal sections of 140μm were cut with a low speed saw (Buehler, Lake Bluff, IL) and mounted on slides using mounting medium (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA). The sections were viewed in a fluorescence microscope (80i Upright Microscope, Nikon, Japan).

Histology and histochemistry

For morphological observation, 5μm-thick paraffin embedded sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and then microphotographs were taken. To examine the pattern of fibrillar collagen, sections were subjected to polarized microscopy (AXIO Imager M1, Zeiss, Göttingen, Germany). Saffranin O/Fast Green staining was used to visualize cartilage proteoglycans and bone. To observe osteoblasts, representative sections were stained for AP using an AP substrate kit (Sigma Diagnostics, St. Louis, MO). To quantify osteoclasts, 10 frozen sections from each specimen were stained for TRAP using a Sigma Diagnostic kit, and multinucleated TRAP positive cells were counted in all sections under high magnification. The numbers of osteoclasts/area were subjected to statistical analysis.

Immunohistochemistry

Ki67 expression was examined by immunohistochemistry using anti-mouse Ki67 monoclonal antibody (clone TEC-3) according to the manufacturer’s instruction (DakoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark). Briefly, 10 serial sections from each sample were treated in a microwave oven for 10 min in 10mM citrate buffer, pH 6.0, and the sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-mouse Ki67 antibody at 1:200 dilution. The sections were incubated at room temperature for 30 min with biotinylated anti-rat IgG at 1:200 dilution, and the signals were visualized by NovaRed after incubation with an ABC kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Normal serum used as primary antibody for negative control did not reveal any signals (data not shown). Ki67 positive cells and total cells in the midpalatal suture were counted on all sections. The percentage of Ki67 positive cells were calculated for each sample and subjected to statistical analysis.

Immunohistochemistry for Type II collagen was carried out using mouse monoclonal collagen II antibody (clone 2B1.5) according to the manufacturer’s instruction (Lab Vision, Fremont, CA). Briefly, sections were pretreated with pepsin at 1mg/ml Tris-HCl, pH2.0 for 10 min at 37°C, and incubated with collagen II antibody for 30 min at 1:100 dilution. MOM kit (Vector Laboratories) was used in the protocol to decrease background staining. Normal serum used as primary antibody in negative control experiments did not reveal any signals (data not shown).

In situ hybridization

Digoxigenin-11-UTP-labeled murine Col1a1 antisense probes were synthesized as described [15]. Standard fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) procedures with tyramide signal amplification (TSA) were used as described previously [16]. Briefly, sections were hybridized with the riboprobe overnight in 50% formamide moisture chamber at 52°C. After washing, sections were incubated for 1hr at RT with a 1:50 dilution of anti-DIG-Fab-HRP (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany), followed by tyramide signal amplification according to the manufacturer’s instruction (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Visualization of FISH was done with a confocal microscope (TE2000, Nikon, Japan).

Statistic analysis

Results were presented as mean ± SD. Cell counts and microCT differences were compared using the unpaired Student’s t-test. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05.

Results

Changes in body weight, suture widths and palatal bone volume

The body weights of the mice with either activated (expansion) or dead opening (sham-operated) loops decreased on days 1 and 3 (Fig. 2, p<0.05). At later time points, there was no significant difference in body weights between these mice and non-operated mice. Although the loops bonded to maxillary molars may disturb food intake at initial stages, the mice recovered quickly. Therefore, the changes we observed following midpalatal suture expansion are unlikely to be caused by systemic physiological responses to the procedure.

Figure 2. Changes of body weight during experimental period.

Body weight curves of non-operated (open square), sham-operated (open triangle) and expansion (filled square) animals. The body weights of expansion and sham operated groups were statistically lower than the non-operated groups at day 1 and day 3 (* p<0.05). However, the body weights recovered after 1 week in both groups.

Suture width measurements from histological sections at day 1 showed that the midpalatal suture was expanded following application of an activated opening loop, with the lateral part of the palatal bone tipped towards the skull base about 2.8 degrees. Since the oral side of the suture was expanded more widely than the nasal side, this movement created greater tensile stress on the oral side than on the nasal side (Fig. 3).

MicroCT analysis showed that the midpalatal suture width increased significantly at day 14, ranging from an increase of 262% at the nasal third to an increase of 295% at the oral third (p<0.001 for both). This increased suture width was initiated as early as day 1 following placement of the opening loop (see Figure 5 below). In the day 28 expansion group, the suture width had increased at the nasal and middle third by 40% and 46% respectively (p<0.001 for both), while it decreased at the oral third by 25% (p<0.05). The maxillary width increased significantly in both day 14 and day 28 groups, with an increase of 6.5% and 8.0% respectively (p<0.001 for both) (Fig. 4 and Table 1).

Figure 5. Effects of midpalatal suture expansion on palatal bones and suture cells.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining of frontal sections of midpalatal sutures of control (A–C) and expansion animals at days 1 (D–F), 3 (G–I), 7 (J–L) and 14 (M–O). (C, F and I): polarized light microscopy of the same specimens shown in B, E and H, respectively. A and B: open arrowheads point to the periosteum within the oral region of the midpalatal suture. G and H: filled arrowheads point to thinner cartilaginous regions along the palatine bony surface. J, K, M–O: arrows point to areas of new bone formation at the edges of palatal bones. Scale bar (A, B and C): 100μm.

Figure 4. Three-dimensional microCT reconstruction of control and expansion maxillae.

Occlusal view of reconstructed maxillae of control (A–D) and expansion (E–H) animals at day 14 (A, B, E and F) and day 28 (C, D, G and H). B, D, F and H are high magnification images of the areas marked by rectangles in A, C, E and G, respectively. E: rectangle marks the expanded suture area. G: rectangle marks the same suture position as the rectangle in E; the suture now is narrower. Scale bar (A): 1.0mm.

The overall changes in palatal bones were reflected in changes in the bone volume fraction (BV/TV, %). Since the total volume (TV) was defined by outlining the palatal bones, the changes in BV/TV reflect changes in the size of bone marrow cavities. In both day 14 and day 28 expansion groups, the BV/TV decreased significantly from 68.0±3.7% to 50.2±0.7% and from 60.9±1.3% to 56.5±1.0% (p<0.05 for both) (Table 1).

Changes in suture morphology in response to expansive force

Histologically, the midpalatal suture of non-operated groups consisted mainly of cartilage, i.e., two masses of chondrocytes covering the edges of palatal bones, separated from each other by a thin layer of fibrous tissue. The oral and nasal periosteal cell layers of the palatal bones were thicker in the region of the midpalatal suture (the cells in this thickened periosteum are referred to as periosteal cells below) (Fig. 5A and B). During the experimental period, the suture in control animals underwent minor changes related to normal growth with a decrease in the number of chondrocytes and an increase in the amount of fibrous tissue. However, the overall width of the midpalatal suture remained constant in these animals. The sham-operated animals showed no difference in overall suture histology compared to non-operated animals and hence these animals were grouped together as controls (data not shown).

In the experimental groups with activated loops, the midpalatal suture was expanded and the collagen fibers were reoriented across the suture starting at day 1 (compare Fig. 5A–C with Fig. 5D–F). At the same time, periosteal cells started to migrate into the suture. At day 3, the suture was filled with spindle-shaped cells aligned in a direction parallel to the direction of mechanical force. The chondrocytes decreased in numbers and formed only 1–2 layers at this stage (Fig. 5G–I). Bone formation was initially observed at the edges of the palatal bones at day 7 (Fig. 5J–L). The width of the suture continued to increase until day 14 with a cellular fibrous tissue filling the suture (Fig. 5M–O). On the oral side, newly formed bone was covered with several layers of chondrocytes with a structure similar to the cartilage layers of the original suture. On the nasal side, bone formed under the nasal epithelium without cartilage. Bone marrow cavities extending to the palatal bone surface were often observed in the experimental groups while this was very rare in the control groups. During the experimental period, no inflammatory cells were observed in the suture area.

To better allow assessment of new bone formation, we labeled bone surfaces by injecting mice with alizarin complexone and calcein at the beginning and end of a 14-day expansion period (see Methods). As shown in Fig. 6, the midpalatal suture area of animals treated for 14 days with the opening loop was filled with calcein-positive material, separating the alizarin-labeled original edges of the palatal bones (compare Fig. 6A, B with Fig. 6C, D).

Figure 6. Dynamic bone labeling of control and expansion maxillae.

Frontal sections of maxillae of control (A and B) and expansion (C and D) animals at day 14. Alizarin complexone-labeled bone surfaces are in red and calcein-labeled surfaces are green. C and D: arrowheads point to new bone formed in the expanded suture area during the 14 days of treatment. Scale bar (A and B): 500μm and 100μm, respectively.

Activated periosteal cells are a major source of new bone and cartilage formation

To obtain insights into cellular mechanisms leading to new suture tissue formation as a result of the expansive force, proliferation and differentiation of periosteal cells was assayed using Ki67 immunohistochemistry, AP histochemical staining, and type I collagen in situ hybridization. In the control groups, Ki67 positive cells accounted for 1.8±0.1% to 4.5±0.4% of total suture cells throughout the experimental period. In the experimental groups, Ki67 positive cells were mainly observed in the region of the periosteal cells at day 1 and day 3, and then scattered throughout the expanded suture at day 7 and day 14. The number of Ki67 positive cells represented 12.0±2.6% to 19.9±1.2% of total suture cells and was significantly higher than that of controls at all time points (p<0.05 for all) (Fig. 7A–E).

Figure 7. Increased cell proliferation of periosteal cells.

Ki67 immunohistochemical staining of frontal sections of midpalatal sutures of control (A) and expansion animals at day 1 (B) and day 7 (C and D). (E) Comparative analysis of Ki67 expression in control groups and expansion groups at days 1, 3, 7 and 14 (* p<0.05). B: Ki67 positive cells (brown) located in the periosteal region. C: Ki67 positive cells scattered within the expanded suture. D: Ki67 positive cells in the cell-rich suture region below the nasal mucosa. Scale bar (A): 100μm.

To further evaluate the contribution of periosteal cells to new bone and cartilage formation, functional changes of periosteal cells were investigated using staining for AP and type I collagen. Periosteal cells in control groups exhibited no or very weak AP staining. Starting at day 1, strong AP staining was observed in periosteal cells in close proximity to palatal bones in the experimental groups. At day 7, strong staining was also seen on the surface of newly formed bone and on the medial aspect of suture cartilage (Fig. 8A–E and data not shown). The expression of type I collagen mRNA showed a similar pattern during the experimental period. At day 1 and day 3, periosteal cells close to palatal bones exhibited significantly increased signal compared to controls, and at day 7 and day 14, Col1a1 mRNA positive cells were distributed along the medial surface of newly formed bone and cartilage (Fig. 8F–J and data not shown).

Figure 8. Expression of osteoblastic markers by periosteal cells.

Frontal sections of midpalatal sutures of control (A and F) and expansion animals at days 3 (B and G), 7 (C and H) and 14 (D, E, I and J). Sections were stained for alkaline phosphatase (AP) (A–E) or Col1a1 transcripts by in situ hybridization (F–J). B, C and D: filled arrows point to increased AP staining (purple) in periosteal cells; C and E: open arrowheads point to osteochondroprogenitor cells; D: closes arrowhead points to chondrocytes. G–J: increased signals for Col1a1 (green) in the same areas as pointed out in B–E. Scale bars (A and F): 100μm.

Decrease of suture cartilage and upregulated osteoclast numbers in response to expansive force

The application of expansive force caused a dramatic decrease in the amount of Saffranin O-positive cartilage, particularly after day 3. In the control groups, there were minimal changes in the intensity of Saffranin O staining, indicating little change in the cartilage proteoglycan content during the experimental period. In contrast, staining with Saffranin O gradually decreased in the cartilage of experimental animals. The change in proteoglycan content was most obvious at day 14 when almost no staining with Saffranin O was observed in the original suture cartilage (Fig. 9A–C and data not shown). However, cartilage forming within the suture on the oral side was at this stage positive for Saffranin O (Fig. 9C) and positive with antibodies against type II collagen (Fig. 9H).

Figure 9. Reduction of secondary cartilage and increased osteoclast numbers in expansion suture.

Frontal sections of midpalatal sutures of control animals at day 3 (A and D) and expansion animals at days 3 (B and E), 7 (H, top) and 14 (C, F and H, bottom). Sections were subjected to Saffranin O/Fast Green staining (A–C) and stained for tartrate resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) (D–F). (G) Comparative analysis of TRAP positive multinucleated cell numbers in control groups and expansion groups at days 1, 3, 7 and 14 (* p<0.05). B: filled arrowhead points to a region of significantly decreased Saffranin O-positive cartilage. C: open arrowheads point to areas of significantly reduced Saffranin O staining. E and F: arrows point to osteoclasts on the nasal side of the palatal bone surfaces (E) and on the surface of bone marrow cavities (F). H: positive staining with collagen II specific antibodies identifies regions of newly formed cartilage within the oral region of the suture (see also C). I: Diagrams showing midpalatal suture at the beginning (up) and end (below) of the 14-day period of suture expansion. Following exposure to expansion force (indicated by arrows and F under the diagram), the suture region is widened, new bone (red) is forming at the palatal edges in the nasal (top) region, and new bone (red) and cartilage (light green) are formed in the oral (bottom) region. Scale bar (A, D and H): 100μm.

The observation that bone marrow cavities were often extended to palatal bone surfaces in experimental groups and microCT results showing significantly increased bone marrow spaces at days 14 and 28 suggested an increased bone remodeling activity. In support of this, the number of osteoclasts along palatal bone surfaces of experimental animals was significantly increased throughout the experimental period, ranging from 60% to 160%. Interestingly, most osteoclasts in the experimental groups were located on the nasal side of the palatal bone surfaces and along the surfaces of bone marrow cavities (Fig. 9D–G and data not shown).

Discussion

In the present study, we have shown that midpalatal suture expansion in mice is a feasible in vivo experimental system for the study of cellular responses of bone and cartilage to mechanical force. Our data indicate that expansive force across the midpalatal suture promotes bone resorption through activation of osteoclasts and bone formation via increased proliferation and differentiation of periosteal cells. Midpalatal suture expansion also leads to decrease of the original secondary cartilage and formation of new cartilage within the suture area on the oral side.

This new cartilage, clearly seen on each side of the suture midline on the oral side at day 14 (Fig. 5), continues to grow towards the nasal mucosa from 14 days to 4 weeks (data not shown). The result is the re-establishment of a suture with the palatine bone margins covered by cartilage and connected by fibrous tissue in the midline; similar to the suture before expansion, but with additional bone added outside each cartilage layer. Thus, the expansion force used here in mice, induced processes of bone and cartilage remodeling, such that the palatine bones are widened and the suture structure re-established after about 4 weeks. This suggests that the magnitude of the force used is both effective and physiologic. Although we have not systemically tested a range of force loads, we settled on using an initial force of 0.56N, since it is capable of expanding the suture of young mice as shown (using microCT) by a significantly increased suture width at day 14 and a return of the width to pre-treatment value. The recovery of body weights three days after the placement of the opening loop also supports the idea that the force is within the physiological range for mice. Finally, it is important to note that we never observed inflammatory cells within the suture of the experimental animals, indicating that the cellular responses described here are not wound healing responses following application of nonphysiological force levels.

The remodeling responses resulting in re-establishment of the suture structure between the expanded palatal bones appear to be different from those others have reported for palatal suture expansion in rats [12, 13]. In the studies of both Takahashi et al. [12] and Kobayashi et al. [13], bone formed within the suture between the cartilage-covered edges of the palatine bone, so that the cartilage ended up being embedded within the bone. Therefore the expansion of the suture in the rat resulted in ossification of the suture and loss of the normal suture layered structure of fibrous tissue sandwiched between cartilage-covered palatal bone plates. In contrast, application of force across the suture in mice induces a process of remodeling and regeneration of the original layered structure.

The processes induced by midpalatal suture expansion are different from those induced by distraction osteogenesis, although the two techniques utilize similar mechanical strategies of expansion to induce bone formation [17, 18]. Unlike distraction osteogenesis, which includes generation of an osteotomy site, midpalatal suture expansion does not require a latency period and shows no sign of the acute inflammation, characterized by edema and neutrophil infiltration, which is associated with distraction osteogenesis. Therefore, the biological responses following midpalatal suture expansion are likely induced by mechanosensitive mechanisms rather than by wound healing processes.

Periosteum contains various cell types and precursor cells that support osteoblastic and chondrogenic differentiation during bone formation and bone growth [19, 20]. Previous studies have shown that periosteal cells of rat tibiae and fibulae exhibit increased AP activity upon cyclic longitudinal loading [21]. Periosteal cells obtained from mandibular periosteum has been shown to express an osteogenic phenotype in response to tensile strain, including upregulated expression of Runx2 and collagen type I mRNA, and increased AP activity [22]. Similarly, as shown here, an expansive force acting on the periosteum induces differentiation of osteogenic progenitor cells to bone-forming osteoblasts in the midpalatal suture area under the nasal mucosa. This response by periosteal cells is also rapid on the oral side in that periosteal cells on each side of an expanding suture express both AP and collagen type I markers as early as day 1. Furthermore, new bone was observed at the edge of palatal bones at day 7, in the region where periosteal cells expressing AP and type I collagen were first observed, and calcein labeling at day 14 showed that a large mass of new bone was formed within the suture area. The higher proliferation rates of periosteal cells in expanding sutures compared to control sutures throughout the experimental period appear to provide a major source of cells for new bone and cartilage formation in the expanded suture area. We noted that the percentage of Ki67-positive cells increased rapidly as early as day 1 after placement of the opening loop, and although the percentage of positive cells remained higher in treated animals than in controls throughout the experimental period, the percentage showed a slow decline after day 1. A transient decrease on day 3 (see Fig. 7E) may be related to post-operative stress as indicated by loss of body weight in treated animals at that day. Support for this conclusion comes from the observation that the number of TRAP-positive cells are also somewhat decreased on day 3 compared with days 1 and 7 (Fig. 9G).

Increased bone marrow spaces of palatal bones as well as increased numbers of osteoclasts in experimental animals, as shown by microCT and TRAP staining, suggest an active bone resorption response. Interestingly, the periosteal osteoclasts were exclusively located on the nasal side. This result is somewhat similar to what is observed during orthodontic tooth movement, where there is a direct correlation between the stress/strain in the periodontal ligament (PDL) and the distribution of osteoclasts in the alveolar bone and PDL; that is, the number of osteoclasts is highest in regions with compressive strain, and lowest in regions with tensile stresses [23]. It is therefore possible that the nasal and oral sides of the palatal bones are subjected to different mechanical stresses, leading to the asymmetric distribution of osteoclasts, during the treatment period. In agreement with this possibility is the finding that application of the opening loop led to a trapezoidal-shaped opening of the midpalatal suture with more widening at the oral than at the nasal side of the suture.

Mechanical forces are known to induce the secretion of soluble mediators, including cytokines, growth factors, and prostaglandins, in mechanosensitive cells such as osteoblasts. Previous studies have shown that cyclic tensile forces increase the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and macrophage-colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) in osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells [24]. Since VEGF and M-CSF, in conjunction with receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL), have been reported to induce osteoclast recruitment and differentiation [25], it is therefore possible that periosteal cells or palatal osteoblasts induce osteoclast differentiation and recruitment via paracrine mechanisms during midpalatal suture expansion.

Interestingly, the application of expansive force across the midpalatal suture causes a decrease of secondary cartilage with a significant loss of proteoglycan-dependent Saffranin O staining. These changes are consistent with earlier results from rat suture expansion studies, in which researchers found that expansive force had an inhibitory effect on chondrogenesis, probably mediated by integrin β1 and cell-extracellular matrix interactions [26]. Moreover, we found that newly formed bone (starting at the oral side) was covered with cartilage so that a suture with a similar structure and width as the original one was formed about 4 weeks after the expansion was started. This indicates an association between mechanical stimulation and cartilage/suture homeostasis. The molecular regulation of this homeostasis remains to be determined, but recent studies of cartilage and bone formation during development combined with what is known about the control of endochondral ossification in growth plate regions of long bones, suggest that several signaling pathways may be involved. For example, Indian hedgehog (Ihh) expressed by prehypertrophic chondrocytes in growth plates of long bones regulates the growth and differentiation of chondrocytes and initiate osteogenic differentiation of osteoblast progenitors in the perichondrium [27]. Thus, it is possible that suture chondrocytes go through similar differentiation processes as their counterparts in growth plates, secreting Ihh at the prehypertrophic stage to regulate the thickness of the cartilage and suture width. Also, canonical Wnt signaling has been implicated in regulating lineage commitment between chondrocytes and osteoblasts; that is, mesenchymal progenitors with low β-catenin level will enter the chondrocyte lineage, while progenitors with high β-catenin level will commit to osteoblasts instead [28, 29]. Therefore, it is conceivable that negative regulators of Wnt signaling, such as Dickkopf homolog 1 (Dkk1), could be concentrated in the midline of the suture thus allowing the differentiation of chondrocytes from mesenchymal progenitors. With the activity of such negative regulators being attenuated around cells some distance away from the midline, chondrocyte differentiation could be limited to a narrow region close to the midline. Thus, the action range of negative regulators of Wnt signaling may regulate the thickness of the cartilage as well as the suture width.

The system described here will allow the use of genetically manipulated mice and thus provides an opportunity for testing these hypotheses as well as other mechanisms by which a tissue containing bone and cartilage senses and responds to mechanical force.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Mary Bouxsein and Nipun Patel for the microCT analyses, done at the Orthopedic Biomechanics Laboratory at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, with support from the NCRR Shared Instrumentation Grant #S10 RR017868. We are grateful to E. Kolpakova Hart, C.Y. Lin, M. Haisraeli-Shalish, Y. Ueki and L.A. Will for technical advice and constructive discussions, S. Plotkina for technical support and Y. Pittel for clerical assistance. This work was supported by research grants AR 36819 and AR 053143 from the National Institutes of Health (to B.R.O).

References

- 1.Raisz LG. Physiology and pathophysiology of bone remodeling. Clin Chem. 1999;45(8):1353–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pavalko FM, Chen NX, Turner CH, Burr DB, Atkinson SA, Hsieh YF, et al. Fluid shear-induced mechanical signaling in MC3T3-E1 osteoblasts requires cytoskeleton-integrin interactions. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:C1591–C1601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walker LM, Publicover SJ, Preston MR, Ahmed MAS, Haj AJE. Calcium-channel activation and matrix protein upregulation in bone cells in response to mechanical strain. J Cell Biochem. 2000;79(4):648–61. doi: 10.1002/1097-4644(20001215)79:4<648::aid-jcb130>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tanaka N, Ohno S, Honda K, Tanimoto K, Doi T, Ohno-Nakahara M, et al. Cyclic mechanical strain regulates the PTHrP expression in cultured chondrocytes via activation of the Ca2+ channel. J Dent Res. 2005;84(1):64–8. doi: 10.1177/154405910508400111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Byron CD, Borke J, Yu J, Pashley D, Wingard CJ, Hamrick M. Effects of increased muscle mass on mouse sagittal suture morphology and mechanics. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol. 2004;279(1):676–84. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.20055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henderson JH, Chang LY, Song HM, Longaker MT, Carter DR. Age-dependent properties and quasi-static strain in the rat sagittal suture. J Biomech. 2005;38(11):2294–301. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vij K, Mao JJ. Geometry and cell density of rat craniofacial sutures during early postnatal development and upon in vivo cyclic loading. Bone. 2006;38(5):722–30. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Copray JC, Jansen HW, Duterloo HS. Effects of compressive forces on proliferation and matrix synthesis in mandibular condylar cartilage of the rat in vitro. Arch Oral Biol. 1985;30(4):299–304. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(85)90001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hinton RJ. Response of the intermaxillary suture cartilage to alterations in masticatory function. Anat Rec. 1988;220(4):376–87. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092200406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kantomaa T, Tuominen M, Perttiniemi P. Effect of mechanical forces on chondrocyte maturation and differentiation in the mandibular condyle of the rat. J Dent Res. 1994;73(6):1150–6. doi: 10.1177/00220345940730060401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haas AJ. Rapid expansion of the maxillary dental arch and nasal cavity by opening the mid-palatal suture. Angle Orthod. 1961;31(2):73–90. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takahashi I, Mizoguchi I, Nakamura M, Sasano Y, Saitoh S, Kagayama M, et al. Effects of expansive force on the differentiation of midpalatal suture cartilage in rats. Bone. 1996;18(4):341–8. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(96)00012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kobayashi ET, Hashimoto F, Kobayashi Y, Sakai E, Miyazake Y, Kobayashi K, et al. Force-induced rapid changes in cell fate at midpalatal suture cartilage of growing rats. J Dent Res. 1999;78(9):1495–504. doi: 10.1177/00220345990780090301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bouxein ML, Myers KS, Shultz KL, Donahue LR, Rosen CJ, Beamer WG. Ovariectomy-induced bone loss varies among inbred strains of mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20(7):1085–92. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fukai N, Eklund L, Marneros AG, Oh SP, Keene DR, Tamarkin L, et al. Lack of collagen XVIII/endostatin results in eye abnormalities. Embo J. 2002;21(7):1535–44. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.7.1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang H, Wanner IB, Roper SD, Chaudhari N. An optimized method for in situ hybridization with signal amplification that allows the detection of rare mRNAs. J Histochem Cytochem. 1999;47(4):431–46. doi: 10.1177/002215549904700402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Isefuku S, Joyner CJ, Simpson AHRW. A murine model of distraction osteogenesis. Bone. 2000;27(5):661–5. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(00)00385-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fang TD, Nacamuli RP, Song HM, Fong KD, Warren SM, Salim A, Carano RAD, Filvaroff EH, Longaker MT. Creation and characterization of a mouse model of mandibular distraction osteogenesis. Bone. 2004;34(6):1004–12. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takushima A, Kitano Y, Harii K. Osteogenic potential of cultured periosteal cells in a distracted bone gap in rabbits. J Surg Res. 1998;78(1):68–77. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1998.5378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanada K, Solchaga LA, Caplan AI, Hering TM, Goldberg VM, Yoo Ju, et al. BMP-2 induction and TGF-beta 1 modulation of rat periosteal cell chondrogenesis. J Cell Biochem. 2001;81(2):284–94. doi: 10.1002/1097-4644(20010501)81:2<284::aid-jcb1043>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dodds RA, Ali N, Pead MJ, Lanyon LE. Early loading-related changes in the activity of glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase and alkaline phosphatase in osteocytes and periosteal osteoblasts in rat fibulae in vivo. J Bone Miner Res. 1993;8(3):261–7. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650080303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanno T, Takahashi T, Ariyoshi W, Tsujisawa T, Haga M, Nishihara T. Tensile mechanical strain up-regulates Runx2 and osteogenic factor expression in human periosteal cells: implications for distraction osteogenesis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63(4):499–504. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2004.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawarizadeh A, Bourauel C, Zhang D, Götz W, Jäger A. Correlation of stress and strain profiles and the distribution of osteoclastic cells induced by orthodontic loading in rat. Eur J Oral Sci. 2004;112(2):140–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2004.00116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Motokawa M, Kaku M, Tohma Y, Kawata T, Fujita T, Kohno S, et al. Effects of cyclic tensile forces on the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and macrophage-colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) in murine osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells. J Dent Res. 2005;84(5):422–7. doi: 10.1177/154405910508400505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Niida S, Kaku M, Amano H, Yoshida H, Kataoka H, Nishikawa S, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor can substitute for macrophage colony-stimulating factor in the support of osteoclastic bone resorption. J Exp Med. 1999;190(2):293–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.2.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takahashi I, Onodera K, Sasano Y, Mizoguchi I, Bae JW, Mitani H, et al. Effect of stretching on gene expression of beta1 integrin and focal adhesion kinase and on chondrogenesis through cell-extracellular matrix interactions. Eur J Cell Biol. 2003;82(4):182–92. doi: 10.1078/0171-9335-00307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kronenberg HM. Developmental regulation of the growth plate. Nature. 2003;423(6937):332–6. doi: 10.1038/nature01657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hill TP, Spater D, Taketo MM, Birchmeier W, Hartmann C. Canonical Wnt/beta-catenin signaling prevents osteoblasts from differentiating into chondrocytes. Dev Cell. 2005;8(5):727–38. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Day TF, Guo X, Garrett-Beal L, Yang Y. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in mesenchymal progenitors controls osteoblast and chondrocytes differentiation during vertebrate skeletogenesis. Dev Cell. 2005;8(5):739–50. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]