Abstract

Conjugation of polysaccharides to carrier proteins has been a successful approach for producing safe and effective vaccines. In an attempt to increase the immunogenicity of two malarial vaccine candidate proteins of Plasmodium falciparum, apical membrane antigen 1 (AMA1) for blood stage vaccines and surface protein 25 (Pfs25) for mosquito stage vaccines, each was chemically conjugated to the mutant, nontoxic Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoProtein A (rEPA). AMA1 is a large (66 kD) relatively good immunogen in mice; Pfs25 is a poorly immunogenic protein when presented on alum to mice. Mice were immunized on days 0 and 28 with AMA1 or Pfs25 rEPA conjugates or unconjugated AMA1 or Pfs25, all formulated on Alhydrogel. Remarkably, sera from mice 14 days after the second immunization with Pfs25-rEPA conjugates displayed over a 1000 fold higher antibody titers as compared to unconjugated Pfs25. In contrast, AMA1 conjugated under the same conditions induced only a 3 fold increase in antibody titers. When tested for functional activity, antibodies elicited by the AMA1-rEPA inhibited invasion of erythrocytes by blood-stage parasites and antibodies elicited by the Pfs25-rEPA conjugates blocked the development of the sexual stage parasites in the mosquito midgut. These results demonstrate that conjugation to rEPA induces a marked improvement in the antibody titer in mice for the poor immunogen (Pfs25) and for the larger protein (AMA1). These conjugates now need to be tested in humans to determine if mice are predictive of the response in humans.

Introduction

While there are several potent experimental adjuvants in the literature many have a limited safety profile in humans, are not of suitable quality for clinical use or access to the clinical grade material is restricted [1–3]. However, carrier proteins, such as Diphtheria Toxoid, CRM197 (a nontoxic mutant of diphtheria toxin), OMPC (outer membrane protein complex of Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B), and Tetanus Toxoid, have been shown as part of effective licensed vaccines to be safe in humans [4–7]. Conjugating bacterial polysaccharides to carrier proteins has dramatically improved the immunogenicity and efficacy especially in children under the age of two [8]. However, the ease of manufacture and access to these clinical grade carrier proteins is often difficult and limited. The mutant, nontoxic carrier protein, recombinant ExoProtein A (rEPA), from Pseudomonas aeruginosa is easily expressed and purified in high yields as a soluble protein from Escherichia coli [9] and is in the public domain. Recombinant EPA has been conjugated to the capsular polysaccharide, Vi, of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi and shown to be more than 90 % efficacy of typhoid fever reduction in 2–5 year old children [10, 11]. While immunologists for many years have conjugated poorly immunogenic peptides and some proteins to carrier proteins for research [12–17], little is known in vaccinology about the ability to conjugate large recombinant antigens covalently to carrier proteins to improve immunogenicity and to elicit functional antigen-specific antibodies in vivo. However, recently Kubler-Kielb et al have shown that conjugation of Pfs25 to itself was able to induce long lived transmission blocking antibodies [18].

Malaria is a mosquito transmitted infectious disease that still severely threatens the health and prosperity of people in the developing world today. Due to the spread of both drug-resistant malaria parasites and insecticide-resistant mosquito vectors, developing a safe and effective malaria vaccine remains a priority. The life cycle of the malaria parasite is complex, including the pre-erythrocytic, asexual blood and mosquito stages. While significant advances have recently been made with pre-erythrocytic vaccines such as RTS,S [19], a few vaccines targeting the asexual blood or mosquito stage have only recently entered the early phase of clinical development. [20–22]. One of the main problems hampering the further development of many potential recombinant protein vaccines is their inability to elicit a robust immune response in humans, and even the inclusion of conventional adjuvants such as aluminum hydroxide may not provide enough help to these targets [23]. In this paper we demonstrate the utility of rEPA conjugation as a strategy for enhancing functional antigen-specific antibodies to large recombinant proteins. Two potential malaria vaccine candidates were chosen as model proteins for conjugating to rEPA. One protein is the asexual blood-stage antigen, Plasmodium falciparum apical membrane antigen 1 (AMA1), which is an integral membrane protein with a molecular weight of 83 kDa [24, 25]. The AMA1 protein is synthesized by parasites late in schizogony, and it is initially located in an apical organelle of merozoites (micronemes). During invasion, the protein is processed to a 66 kDa product and relocated onto the surface of merozoites. The other model protein is the P. falciparum surface protein 25 (Pfs25) which is a 25 kDa protein expressed by parasites at the onset of zygote formation in the mosquito midgut [26].

Here we demonstrate that AMA1 and Pfs25 can be conjugated to rEPA successfully. AMA1-rEPA and Pfs25-rEPA, when formulated on Alhydrogel, elicited significantly higher antibody responses compared to when unconjugated AMA1 and Pfs25 were formulated on Alhydrogel alone. Furthermore, the conjugation process did not destroy critical epitopes required to elicit a functional immune response. Purified IgG from mice immunized with AMA1-rEPA inhibited invasion of P. falciparum into red cells. The Pfs25-rEPA mouse immune sera inhibited oocyst formation in the midgut of the mosquito.

Materials and Methods

Expression and purification of recombinant mutant of Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoProtein A

The rEPA expression plasmid, pVC45D/PE553D, was provided by Joseph Shiloach (NIDDK, NIH) [9, 27]. For bench scale expression and production of the lot used in the mouse immunogenicity studies, E. coli cells BL21(λDE3) were transformed, and overnight colonies were used to inoculate 1 L of LB Broth which was then grown at 37°C in a rotating shaker at 250 rpm until the A600 reached an OD of 0.6. Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside was added to the culture to a final concentration of 1 mM to induce the expression of the recombinant rEPA. After 3 h induction, the supernatant of the culture was harvested by centrifugation, from which the rEPA was purified using one step of hydrophobic interaction chromatography (Phenyl Sepharose 6 Fast Flow, GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) and two steps of anion exchange (DEAE Sepharose Fast Flow and SOURCE 30Q, GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ).

For scale up and large scale production of rEPA the modified rEPA gene was cloned into the kanamycin resistant E. coli expression plasmid pET-24a(+) (Novagen, San Diego, CA). The gene was amplified using pVC45D/PE553D as template and exoA-NF (5′-GGGCAACATATGAAAAAGACAGCTATCGCG-3′) and exoA-SR (5′-CCGGTCGGAGCTCTTACTTCAGG-3′) as primers.

The E. coli production clone was fermented with defined media in 5L bioreactors as previously described [28]. Fermentation broth was harvested using continuous centrifugation at 12,000 × g and clarified supernatant was further processed by microfiltration 750,000 molecular weight cut off (MWCO), size 5 (UFP-750-E-5, GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) and ultrafiltration/diafiltration (UF/DF) cartridge 10,000 MWCO, size 5, (UFP-10-C-5, GE Healthcare) as suggested by the manufacturer. The UF/DF buffer consisted of 20 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.2. Diafiltered and concentrated fermentation bulk was stored at −80°C.

The fermentation bulk was thawed at 4°C and diluted with water until the conductivity was < 5 mS/cm, pH adjusted to 5.9 ± 0.2, filtered using a 0.8 – 0.45 μm filter and captured using a Capto Q column (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). The load capacity of rEPA was ~5 mg/mL resin and the linear flow rate was between 300 – 400 cm/hr. Recombinant EPA was purified by step elution starting with 20 mM Bis-Tris, 150 mM NaCl, pH 5.9 to remove impurities, and rEPA was eluted with 20 mM Bis-Tris, 500 mM NaCl, pH 5.9. The elution pool was diluted with 3.6 M ammonium sulfate to a final concentration of 0.9 M ammonium sulfate, pH 7.4. A Phenyl Sepharose HP column (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) was equilibrated with 20 mM Tris-HCl, 0.9 M ammonium sulfate, pH 7.4 prior to the sample being loaded at a linear flow of 100 cm/hr. Recombinant EPA was eluted with 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4 and diluted with water until the conductivity was < 5 mS/cm, pH adjusted to 6.5 prior to loading on a Q Sepharose Fast Flow column (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) equilibrated with 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.5 at a linear flow of 100 cm/hr. Recombinant EPA was eluted with 20 mM Tris-HCl, 250 mM NaCl, pH 6.5. The elution pool was loaded on a Superdex 75 column (60 cm height, GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) equilibrated with saline such that the load volume did not exceed 6% of a column volume. The gel permeation elution peak was collected and the concentration was determined by absorbance 280 nm. Bulk rEPA (MW 67 kDa) was biochemically characterized by amino-terminal sequencing, electro-spray ionization mass spectrometry, and reverse-phase HPLC following similar procedures as previously described [28].

Preparation of the AMA1-rEPA conjugate

The purified rEPA was buffer-exchanged into conjugation buffer [1 x PBS (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 5 mM EDTA (Quality Biological Inc., Gaithersburg, MD), pH 7.2], using a 5 kDa MWCO spin filter (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and concentrated to 5 mg/mL. An excess of 10 mM N-[ε-maleimidocaproyloxy]sulfosuccinimide ester (Sulfo-EMCS) (Pierce Inc., Rockford, IL) dissolved in conjugation buffer was added to the 5 mg/mL solution of rEPA and incubated for 20 min at room temperature (RT). Unreacted Sulfo-EMCS was removed by dialyzing against the conjugation buffer. The content of maleimide group on the activated rEPA (moles of maleimide/mole of rEPA) was determined indirectly with Ellman’s reagent [5, 5′-Diothio-bis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid), Pierce Inc., Rockford, IL] by measuring the consumption of free thiol of L-cysteine·HCl (Pierce Inc., Rockford, IL) used to titrate the activated protein [29]. AMA1 from the P. falciparum FVO malaria parasite clone was expressed as a recombinant 62 kDa protein in Pichia pastoris [30]. AMA1 was buffer-exchanged into thiolation buffer [0.1 M NaHCO3 (Mallinckrodt Baker Inc., Phillipsburg, NJ), 5 mM EDTA, pH 8.3] and adjusted to 5 mg/ml. An excess of 100 mM DL-N-acetylhomocysteine thiolactone (Sigma Aldrich Inc., St Louis, MO) dissolved in thiolation buffer was added to the AMA1 solution and incubated at 4°C overnight. After reaction the thiolated AMA1 was exchanged into the conjugation buffer removing any unreacted DL-N-acetylhomocysteine thiolactone. The content of free thiol on the activated AMA1 (moles of free thiol/mole of AMA1) was determined directly with Ellman’s reagent by comparison to the L-cysteine·HCL used as standard. A 2 fold excess, based on maleimide: thiol ratio, of thiolated AMA1 was added to maleimide derivatized rEPA (maleimide rEPA) and mixed for 1 h at RT. The conjugation reaction mixture was applied directly onto a Superdex 75 gel filtration column and eluted in PBS. Three AMA1-rEPA conjugate fractions (AMA1-rEPA F1, AMA1-rEPA F2 and AMA1-rEPA F3) from high to low molecular weight were obtained by pooling gel filtration fractions as determined by SDS-PAGE analysis.

Preparation of Pfs25-rEPA conjugate

Pfs25 from P. falciparum NF54 isolate is expressed as a 22 kDa protein in Pichia pastoris [31] and was thioylated as for AMA1. A 1.5-fold excess of thioylated Pfs25 was added to maleimide rEPA and mixed for 1 h at RT. Unreacted rEPA was removed by buffer exchanging into Ni-NTA binding buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, pH 8.0) and then passed through a Ni-NTA Superflow column (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). After washing with Ni-NTA washing buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, pH 8.0), the Pfs25-rEPA conjugate was eluted with Ni-NTA elution buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole, pH 8.0). Unreacted Pfs25 was removed by applying the Ni-NTA eluent onto a Superdex 75 gel filtration column. Two fractions of the Pfs25-rEPA conjugate (Pfs25-rEPA F1 and Pfs25-rEPA F2) from high to low molecular weight were obtained by pooling different fractions of gel filtration according to the SDS-PAGE.

Characterization of Conjugates

Endotoxin levels were measured by Limulus amoebocyte lysate in a 96-well plate with chromogenic reagents and PyroSoft software (Associates of Cape Cod Inc., East Falmouth, MA) as described by the manufacturer. The endotoxin levels were 0.088 EU/μg AMA1, 0.113 EU/μg AMA1 and 0.261 EU/μg AMA1 for AMA1-rEPA F1, AMA1-rEPA F2 and AMA1-rEPA F3 respectively; 0.075 EU/μg Pfs25 and 0.063 EU/μg Pfs25 for Pfs25-rEPA F1 and Pfs25-rEPA F2 respectively. The protein-carrier ratio was determined by amino acid analysis (AAA) of the conjugates performed by W. M. Keck Facility (Yale University, New Haven, CT). The concentrations of AMA1 or Pfs25 within the conjugates were calculated based on average ratios determined from the AAA [32]. The final products of the AMA1 and Pfs25 conjugates were examined by SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis probed with either goat anti-exotoxin antisera (List Biological Laboratories, Campbell, CA) or anti-AMA1 monoclonal antibody (4G2dc1) [33] or anti-Pfs25 monoclonal antibody (4B7) [34]. To assess the lot-to-lot variability of the conjugate, three independent batches of Pfs25-rEPA were prepared as described above. Pfs25-rEPA conjugates were analyzed using size exclusion chromatography (SEC) with in-line multiangle light scattering (MALS), refractive index, and ultraviolet detection largely as described by Stogniew and Williams [35] and Shimp et al [28]. A Waters (Milford, MA) 2695 HPLC, Waters 2996 PDA detector, Wyatt (Santa Barbara, CA) Dawn EOS Light Scattering detector, and Wyatt Optilab DSP refractive index detector were in series for acquiring the data, and the Wyatt Astra V software suite was used for data processing. For separation, a Tosoh Bioscience (Montgomeryville, PA) TSK gel G3000SWxl and G4000SWxl 7.8 mm ID × 30 cm, 5μm particle size analytical column were used with a TSK gel Guard SWxl 6.0mm ID × 4 cm, 7μm particle size guard column. The column was equilibrated in mobile phase (1.04 mM KH2PO4, 2.97 mM Na2HPO4, with 308 mM NaCl, 0.02% azide) at 0.5 mL/min prior to sample injection. Prior to analysis Pfs25-rEPA was filtered through a 0.45 μm PVDF centrifugal filtration device [Ultrafree-MC 0.45μm, PVDF, Durapore, Millipore (Bedford, MA)] spun at 2000 RPM for 2 minutes. Approximately 75 μg of sample was injected using an isocratic run at 0.50 mL/min in mobile phase for 60 minutes. For size comparisons 10 μL of Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA) Gel Filtration Standard HPLC standards were run and a 25 μL injection of 5 mg/mL bovine serum albumin was run for EOS MALS detector normalization.

Animals and immunization

Animal studies were carried out in compliance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines and with an Animal Care and Use Committee-approved protocol. Studies were carried out in mice either with AMA1 and its conjugates (AMA1-rEPA F1, AMA1-rEPA F2 and AMA1-rEPA F3) or with Pfs25 and its conjugates (Pfs25-rEPA F1 and Pfs25-rEPA F2), all were formulated on 1600 μg/mL aluminum hydroxide gel (Alhydrogel®, Brenntag Biosector, Denmark). To determine the percentage of protein bound to Alhydrogel the formulation was centrifuged and the supernatant was analyzed by SDS-PAGE silver staining. After demonstrating that all conjugates completely bound to Alhydrogel in the presence of PBS, immunogenicity studies were performed for AMA1 and its conjugates on 20 groups of 10 BALB/c mice (Charles River Laboratories, Frederick, MD) at 0.003, 0.01, 0.03, 0.1 and 0.3 μg of AMA1. For Pfs25 and its conjugates, immunogenicity studies were performed on 9 groups of 10 BALB/c mice at 0.1, 0.5 and 2.5 μg of Pfs25. Vaccine formulations were administered intramuscularly on Days 0 and 28. Animals were observed after immunization at 60 min and 24 hrs post-injection for adverse effects. Adverse effects were assessed by looking at systemic reactogenicity (appearance, activity, appetite); and local injection site reactogenicity (erythema, induration and necrosis). Serology was performed on sera collected on Day 42, 14 days after the second vaccination.

Immunological assays

Day 42 sera were obtained for AMA1 and Pfs25 antibody determinations by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as described previously [36]. Antigen-specific IgG subclasses in mice were determined by ELISA as described previously [36]. To examine the biological activity of anti-AMA1 antibodies, anti-AMA1 IgGs purified from mouse sera were tested in a standardized parasite growth inhibition assay (GIA) as described previously [30, 37]. To determine the transmission blocking activity of anti-Pfs25 antibodies, membrane feeding assays were performed on mouse sera as described previously [38, 39]. A nonlinear regression fit of the data to a simple hyperbolic equation was performed using % inhibition = 100· [C]/(Ab50 + [C]), where [C] is the anti-Pfs25 ELISA units and Ab50 is the anti-Pfs25 ELISA units giving 50% inhibition of oocyst.

Statistical analysis

To test for a significant level of enhancement of antibody reponses between AMA1, AMA1-rEPA F1, AMA1-rEPA F2 and AMA1-rEPA F3 or Pfs25 and Pfs25-rEPA F1 and Pfs25-rEPA F2, a Kruskal-Wallis One-Way ANOVA was performed; P values of < 0.025 were considered significant. If the Kruskal Wallis test was significant, then a post hoc analysis was performed with Student-Newman-Keuls pairwise comparison; P values of < 0.05 were considered significant. The effect of antigen dose on antibody response was tested by Spearman Rank Correlation for day 42. A ρ value > 0 and significance of P value < 0.05 was required for a dose response.

Results

Preparation and characterization of AMA1-rEPA and Pfs25-rEPA conjugates

In previous studies, rEPA expressed in E. coli was purified either from whole cell lysates or from the periplasmic space [9, 15, 27, 40]. SDS-PAGE analysis of induced bacterial cell cultures indicated that a large portion of the soluble rEPA was secreted into the culture supernatant. The rEPA was captured from the culture supernatant by either Phenyl Sepharose for the small scale purification or Capto Q for the large scale purification. Isolation of soluble rEPA from culture supernatant greatly simplified the purification procedure.

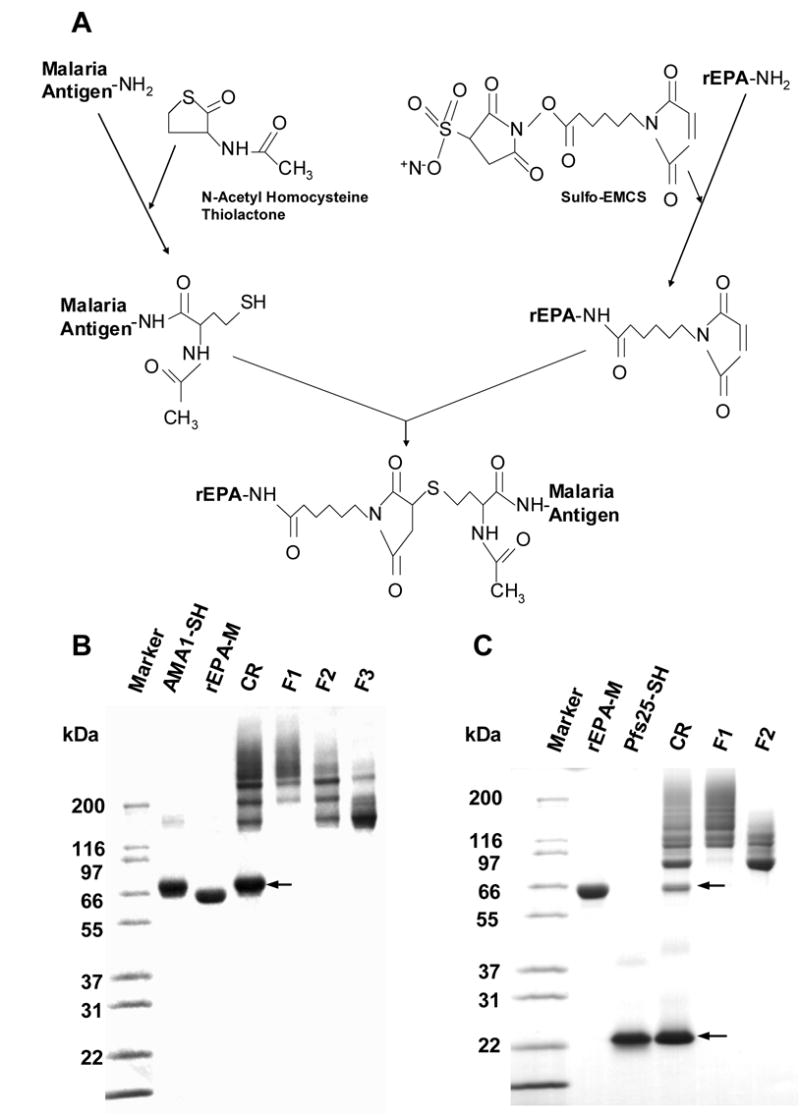

The malaria antigens AMA1 or Pfs25 were chemically conjugated to rEPA in two steps. The malaria antigens were thiolated using DL-N-acetylhomocysteine thiolactone, and rEPA was modified using Sulfo-EMCS which lead to the addition of maleimide group(s) and a 6 carbon linker acylated on the ε amino group of lysines (Fig 1 A). After mixing, unreacted AMA1, Pfs25 or rEPA was removed from the conjugation reaction mixture. Three fractions of AMA1-rEPA and two fractions of Pfs25-rEPA were isolated from the reaction mixture based on molecular weight (Fig 1 B and C).

Figure 1.

Preparation and SDS-PAGE analysis of conjugates under non-reducing condition. A. Schematic procedure of conjugation using AMA1 and Pfs25 as malaria antigens, rEPA as carrier. Sulfo-EMCS was used to add maleimide groups to rEPA and DL-N-acetylhomocysteine thiolactone to thiolate the malaria antigens. B. SDS-PAGE of AMA1-rEPA conjugate. C. SDS-PAGE of Pfs25-rEPA conjugate. Marker: molecular weight markers; rEPA-M (~67 kDa): maleimide rEPA; AMA1-SH: thiolated AMA1 (~62 kDa); Pfs25-SH: thiolated Pfs25 (~22 kDa); CR: conjugation reaction; F1: conjugate fraction 1; F2: conjugation fraction 2; F3: conjugation fraction 3. Arrows on both B and C indicate the unreacted AMA1-SH or Pfs25-SH, respectively.

The AMA1-rEPA Fraction 1 (F1) contained high molecular weight conjugates (> ~180 kDa) with a ratio of AMA1 to rEPA greater than 2:1 as judged by SDS-PAGE (Fig 1 B) including cross-linked AMA1-rEPA conjugates visualized as high molecular weight aggregates on the gel. The AMA1-rEPA Fraction 2 (F2) contained conjugates in the molecular weight range of ~ 120 to ~ 240 kDa with a ratio of AMA1 to rEPA between 1:1 to 3:1, whereas the AMA1-rEPA Fraction 3 (F3) contained predominately low molecular weight (< ~180 kDa) 1:1 conjugates (Fig 1 B). Western blot analysis with either anti-rEPA polyclonal antibodies or with monoclonal antibody anti-AMA1 4G2dc1 displayed reactivity with all visible bands including high molecular weight aggregates (data not shown). The mAb 4G2dc1 only recognizes conformational epitopes of P. falciparum AMA1, suggesting that AMA1 remained correctly folded after conjugation. Given that the distribution of amino acids in AMA1 and rEPA are relatively different, the amino acid analysis data was used to calculate the average molar ratios between AMA1 and rEPA (AMA1: rEPA). The average molar ratios of AMA1: rEPA for AMA1-rEPA F1, AMA1-rEPA F2 and AMA1-rEPA F3 were 2.0, 1.7 and 1.4, respectively. These molar ratios were then used to calculate the concentration of AMA1 to be used in the mouse dose ranging study.

Pfs25-rEPA Fraction 1 (F1) contained high molecular weight conjugates (> ~ 120 kDa) and also cross-linked Pfs25-rEPA conjugates visualized as high molecular weight aggregates on the SDS-PAGE. The Pfs25-rEPA Fraction 2 (F2) contained low molecular weight conjugates (< ~ 120 kDa) predominately of a 1:1 conjugate as judged by SDS-PAGE (Fig 1 C). Western blot analysis with either anti-rEPA polyclonal antibodies or with a transmission blocking anti-Pfs25 4B7 monoclonal antibody displayed reactivity with all visible bands as well as high molecular weight aggregates (data not shown). The average molar ratios, as calculated by AAA, of Pfs25: rEPA for Pfs25-rEPA F1 and Pfs25-rEPA F2 were 2.1 and 1.5, respectively.

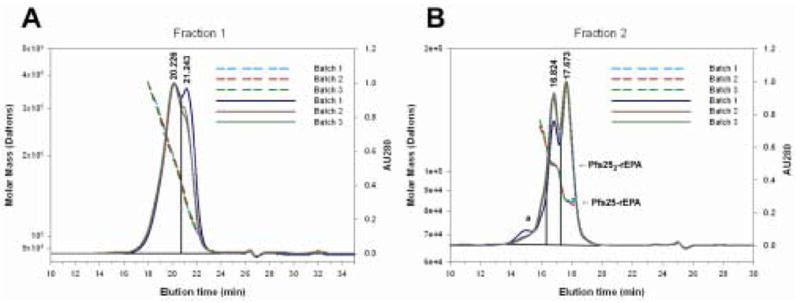

To determine lot-to-lot variability three independent batches of Pfs25-rEPA were conjugated and characterized by SDS-PAGE, AAA and SEC-MALS-HPLC. The Coomassie blue stained SDS-PAGE profiles of the three different Pfs25-rEPA batches were similar (data not shown). The average molar ratios of Pfs25: rEPA based on AAA were consistent from lot to lot. The mean values of the average molar ratio obtained from these three conjugate batches were 2.03 ±0.05 and 1.61 ±0.06 for Pfs25-rEPA F1 and F2 respectively (mean ± SD). The solution state and weight average mass of the conjugates evaluated by SEC-MALS-HPLC showed that for Fraction 1 the mass of the conjugated protein ranged from ~100 to 400 kDa with the population separating into two peaks with the area comprised of 65% and 35% at 20.2 and 21.2 minutes, respectively (Fig. 2A). Analysis of fraction 2 showed that the majority of the conjugates were comprised of two forms with a ratio of Pfs25 to rEPA of 1:1 (17.7 min., ~87,000 Da) and 2:1 (16.8 min. ~108,000 Da). Integration of the respective areas showed that Pfs25-rEPA comprised 49% and Pfs252-rEPA comprised 39%, while a larger population of conjugates represented 12% of the total area (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Biochemical analysis of Pfs25-rEPA conjugates by size exclusion and inline multi-angle light scatter. Panels A and B show overlays of the absorbance 280 nm and multi-angle light scatter traces of the three different batches of Pfs25-rEPA for fractions 1 and 2, respectively. Solid and dashed lines represent absorbance 280 nm and MALS results, respectively.

Conjugation to rEPA enhances anti-AMA1 and anti Pfs25-specific antibody responses

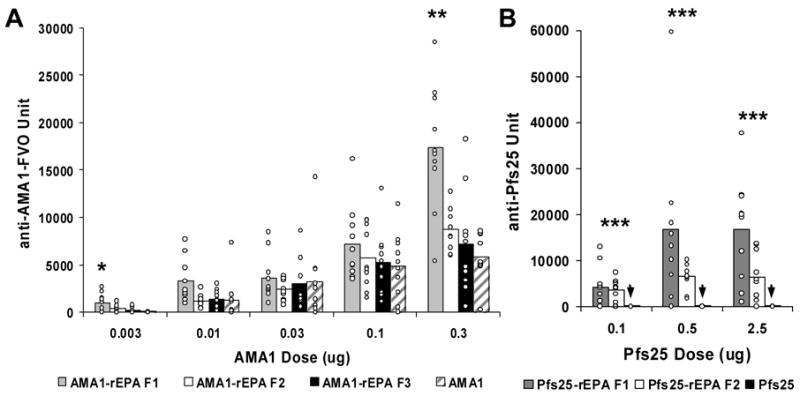

Studies in mice were performed to assess the safety, immunogenicity and functionality of the AMA1-rEPA and Pfs25-rEPA conjugates compared to AMA1 and Pfs25 formulated on Alhydrogel. Mice received two intramuscular immunizations on day 0 and 28 and sera were collected on Day 42. No vaccine related adverse events occurred in any of the animals. ELISA was used to measure Day 42 anti-AMA1 and anti-Pfs25 antibody responses for each individual serum sample. For AMA1 at the 0.03 and 0.01 μg doses there was no significant difference in anti-AMA1 responses between AMA1-rEPA F1, F2, F3 and AMA1 groups. However, at the 0.3 μg dose which was the top of the dose response curve (data not shown), AMA1-rEPA F1 induced significantly higher antibody titers compared to AMA1-rEPA F2, F3 and AMA1 (Kruskal Wallis test: P = 0.0081. Student Newman-Keuls test: P = 0.0322, P = 0.0016 and P = 0.0008, respectively, Fig 3 A). For the 0.003 μg dose group, AMA1-rEPA F1, F2 and F3 displayed significantly higher antibody titers compared to AMA1 (Kruskal Wallis test: P = 0.0001. Student Newman Keuls test: P= 0.0001, P = 0.0011 and P = 0.0098, respectively, Fig 3 A). In the 0.003 μg dose group for AMA1-rEPA F1, seven out of ten mice responded with an anti-AMA1 titer greater than 100 units, whereas for the AMA1 group none of the mice responded with titers greater than 100 units (Fig 3 A). Significant dose responses were displayed for all AMA1-rEPA conjugate fractions and AMA1 (AMA1-rEPA F1 ρ = 0.8448 and P = 0.0000, AMA1-rEPA F2 ρ = 0.8948 and P = 0.0000; AMA1-rEPA F3 ρ = 0.7771 and P = 0.0000 and AMA1/Alhydrogel ρ = 0.7771 and P = 0.0000).

Figure 3.

AMA1 and Pfs25-specific antibody responses in mice. A. All animals were immunized, with AMA1(hatched bars), AMA1-rEPA F1 (grey bars), AMA1-rEPA F2 (white bars) or AMA1-rEPA F3 (black bars) formulated on Alhydrogel, twice at 4 week intervals by i.m. injection and bled 14 days after the second injection. Mice were immunized with 0.003, 0.01, 0.03, 0.1 and 0.3 μg dose of AMA1. B. Mice immunized with Pfs25 (black bars on base line, identified by the arrow), Pfs25-rEPA F1 (grey bars) or Pfs25-rEPA F2 (white bars) formulated on Alhydrogel, twice at 4 week intervals by i.m. injection and bled 14 days later. Mice were immunized with 0.1, 0.5 and 2.5 μg dose of Pfs25. All ELISA results are presented as units compared to reference mouse anti-AMA1 or Pfs25 sera that have 35,000 and 25,000 units, respectively. (i.e., they give an OD=1.0 at dilutions of 1:35,000 and 1: 25,000, respectively, in the standard ELISA with AMA1 and Pfs25 plate antigens). Results are expressed as the mean of ELISA values of individual animals in each group. Individual ELISA values are represented by small circles. * Indicates that the anti-AMA1 antibodies are significantly higher in the AMA1-rEPA groups compared to the AMA1 group (P < 0.0081); ** Indicates that the anti-AMA1 antibodies are significantly higher in the AMA1-rEPA F1 group compared to the AMA1-rEPA F2, AMA1-rEPA F3 and AMA1 groups (P <0.0005); *** Indicates that the anti-Pfs25 antibodies are significantly higher in the Pfs25-rEPA conjugate groups compared to the Pfs25 group (P < 0.0019).

Anti-Pfs25 antibody responses for Pfs25-rEPA F1 and Pfs25-rEPA F2 were significantly higher (Student Newman Keuls; Dose 0.1 μg: Pfs25-rEPA F1 vs Pfs25/Alhydrogel P = 0.0002, Pfs25-rEPA F2 vs Pfs25/Alhydrogel P = 0.0003; Dose 0.5 μg: Pfs25-rEPA F1 vs Pfs25/Alhydrogel P = 0.0000, Pfs25-rEPA F2 vs Pfs25/Alhydrogel P = 0.0016; Dose 2.5 μg: Pfs25-rEPA F1 vs Pfs25/Alhydrogel P = 0.0000, Pfs25-rEPA F2 vs Pfs25/Alhydrogel P = 0.0019 ) than those induced by Pfs25 at all dose groups (Fig 3B). Pfs25 is known to be a poor immunogen and typically when formulated on Alhydrogel, since protein doses upwards of 5 μg are required before an immune response as judged by ELISA is observed in immunized mice (data not shown). Significant dose responses were displayed for Pf25-rEPA F1 conjugate (ρ = 0.5330 and P = 0.0012) but not for Pf25-rEPA F2 (ρ = 0.2736 and P = 0.0718)and unconjugated Pfs25(ρ = 0.2566 and P = 0.0855). However, a plateau was already reached at the 0.5 μg dose.

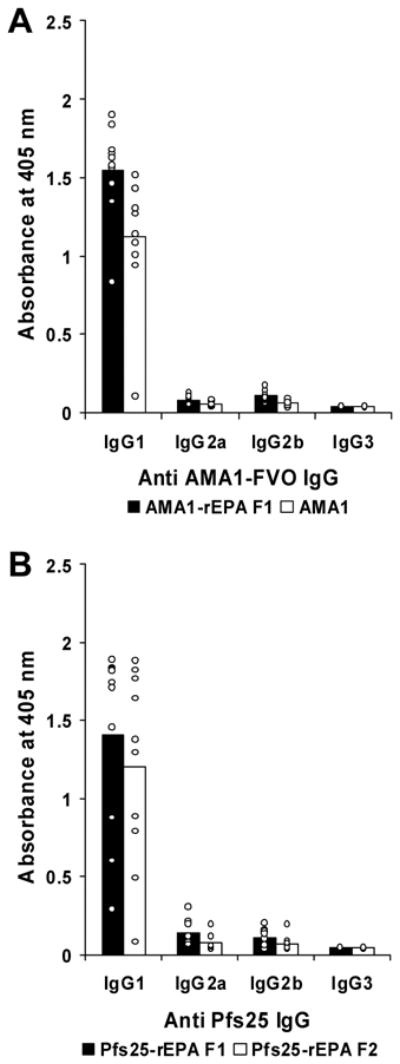

IgG subclass analysis was performed on the post-immunization mouse sera to characterize the immune responses elicited by AMA1 and Pfs25 conjugates. AMA1 and Pfs25 conjugates formulated on Alhydrogel induced a pattern of IgG subclass consistent with that seen with a Th2-type response and identical to their unconjugated counterparts, with almost all of the anti-AMA1 and anti-Pfs25 antibodies being of IgG1 subclass with little or no IgG 2a subclass produced (Fig 4 A and B).

Figure 4.

Subclass analysis of AMA1 and Pfs25-specific mouse antibodies. A. Antibody IgG subclassees in BALB/c mice 2 weeks post-secondary immunization with 0.3 μg dose groups of AMA1-rEPA F1 (black bar) and AMA1 (white bar). B. Antibody IgG subclasses in BALB/c mice 14 days post-secondary immunization with 2.5 μg dose groups of Pfs25-rEPA F1 (black bar) and Pfs25-rEPA F2 (white bar). All serum samples were diluted 5000 fold, and the concentration of the different anti-mouse IgG subclasses were normalized to give comparable reactivity on homologous mouse myeloma proteins. Mean OD values of IgG subclass of each group are represented by bars. Individual OD values of IgG subclass of mice in each group are represented by small circles.

Conjugation to rEPA elicits functional anti-AMA1 and anti Pfs25-specific antibodies

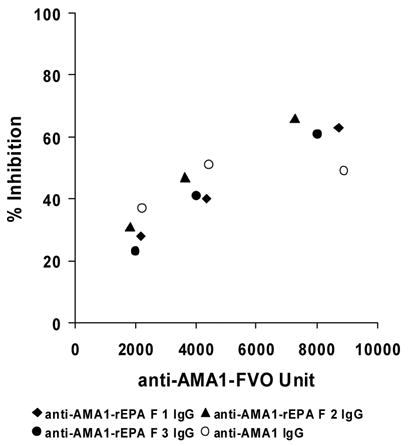

In order to evaluate the functional activity of anti-AMA1 and anti-Pfs25 antibodies elicited by the AMA1-rEPA and Pfs25-rEPA conjugates, growth inhibition assay (GIA) and transmission blocking assay (TBA) were performed, respectively. IgG antibodies from the AMA1 0.3 μg dose groups were purified, pooled and concentrated to 5 mg/ml for direct comparison of the relative levels of functional antibody between AMA1-rEPA conjugates and AMA1 groups. The purified IgGs were incubated with P. falciparum FVO parasite and the ability of IgG to inhibit in vitro growth was assessed using a standardized in vitro inhibition procedure. As shown in Figure 5, all IgGs elicited by AMA1-rEPA conjugates and AMA1 exhibited the ability to inhibit in vitro growth with a maximal growth inhibition of ~ 65 %.

Figure 5.

Inhibition of parasite invasion with day 42 purified mouse anti-AMA1 IgG. Day 42 mouse sera from 0.3 μg dose groups of AMA1-rEPA F1 (closed diamond), AMA1-rEPA F2 (closed triangle), AMA1-rEPA F3 (closed circle) and AMA1 (open circle) were pooled respectively. Total IgG was purified from each of the pooled sera and adjusted to a concentration of 5 mg/ml. The pooled IgG was used in the standardized GIA with homologous FVO strain of P. falciparum parasite and tested in three 2-fold serial dilutions. Growth inhibition was measured by biochemical assay of parasite lactate dehydrogenase 40 hours after initiation of cultures. Results are plotted as % inihibition relative to control cultures versus the anti-AMA1 ELISA values in the wells (in standardized units) for the individual IgG samples.

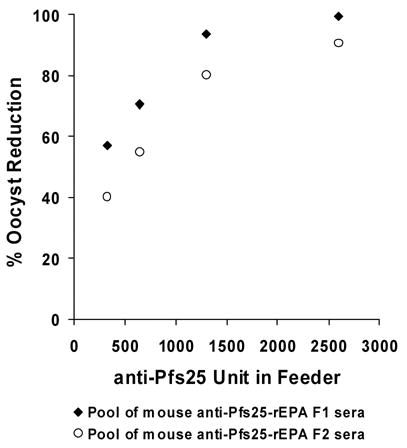

Pools of mouse anti-Pfs25-rEPA F1 and anti-Pfs25-rEPA F2 sera were obtained respectively by pooling six high titer sera (> 9000 ELISA unit) from the mice immunized with 2.5 μg and 0.5 μg antigen dose. Transmission blocking activity was performed by adding anti-mouse sera into mosquito membrane feeders and the number of oocysts formed in the mosquito midgut were counted one week later. Transmission blocking activity was observed for both F1 and F2 and the anti-Pfs25 antibody required to give a 50 % reduction in oocyst count (Ab50) was 269 units with near 100 % reduction being observed at 2512 units (Fig 6), comparable to the Ab50 observed with other Pfs25 formulations [38]. The doses of Pfs25 used in this experiment were too low to elicit high enough antibody responses when formulated on Alhydrogel. However, when mice were immunized with 5 μg of Pfs25, an Ab50 of ~ 300 units was also observed (K. Miura, unpublished data).

Figure 6.

Transmission blocking assay of Pfs25 specific mouse serum. Day 42 mouse sera from 0.5 or 2.5 μg dose groups of Pfs25-rEPA F1 (closed circles) and Pfs25-rEPA F2 (open circle) were pooled respectively. Two fold serial dilutions of the pooled sera were added into the membrane feeders along with cultured P. falciparum NF54 gametocytes. Fed mosquitoes were maintained for 8 days and midguts were dissected and stained for microscope counting of oocysts. Results are presented as % reduction in oocyst numbers relative to a pool of pre-immunization mouse sera versus the anti-Pfs25 ELISA titers of the sera in the feeder.

Discussion

Both AMA1 and Pfs25 antigens of P. falciparum have been identified as leading malaria vaccine candidates for blood stage and sexual stage, respectively. However, in human trials to date AMA1 and Pvs25, the P. vivax orthologue of Pfs25, formulated on Alhydrogel [20, 23] did not generate impressive levels of functional antibody and it is thought that higher levels of antibody will be required if such vaccines are to be effective. In this study we demonstrate that conjugating recombinant proteins, such as AMA1 or Pfs25, to the carrier protein rEPA significantly increased antigen specific antibody level, and induced antibodies with functional activity, compared to the antigen alone formulated on Alhydrogel. The results obtained here exhibit a promising approach to enhance the immunogenicity of malarial vaccine candidates.

To date several carrier proteins have been used in several effective licensed vaccines which have good safety profiles. However, one potential problem concerning the use of carrier proteins, already used as part of the Expanded Programme on Immunization, is that pre-existing anti-carrier antibodies may have a deleterious effect on the immune response of the conjugate [41].

ELISA analysis of sera from mice receiving AMA1 or AMA1-rEPA conjugates formulated on Alhydrogel was performed and showed that at the 0.3 μg dose, the high molecular weight conjugate, AMA1-rEPA F1, elicited a significant increase in anti AMA1 antibody titer compared to AMA1-rEPA F2, AMA1-rEPA F3 or AMA1. This dose was shown to be the plateau (Mullen et al, unpublished data) for the immune response to both the conjugate and the unconjugated AMA1. Given that in the 0.3 μg formulation groups, all mice received the equivalent dose of AMA1, the significant increase in immunogenicity may be attributed to the high molecular cross-linked aggregates observed with AMA1-rEPA F1. The improved response of the conjugate may be attributed to the ability of rEPA to provide T-helper epitopes and hence effectively provide T cell help for AMA1-specific antibody responses.

Pfs25 formulated on Alhydrogel is poorly immunogenic. Significant anti-Pfs25 immune responses were elicited in mice immunized with Pfs25-rEPA conjugates at the 0.1 μg dose and reached a plateau at the 0.5 μg dose, while there were almost no responses elicited by Pfs25 formulated on Alhydrogel, even at the highest dose of 2.5 μg. While not significant, there is a tendency for the antibody levels induced by Psf25-rEPA F1 to be higher than those elicited by Pfs25-rEPA F2. This increased immunogenicity may be attributed to the high molecular weight cross-linked aggregates in the F1 compared to F2 fraction. Both conjugates of AMA1-rEPA and Pfs25-rEPA formulated on Alhydrogel induced a Th2-like immune response in mice that is characterized by the dominant IgG1 subclass.

The critical B cell epitopes in both AMA1 and Pfs25 must be of a certain conformation in order to induce a functional response [34, 42–44]. One potential caveat of chemically modifying and conjugating proteins is the possibility of disrupting critical B-cell epitopes and losing the ability to induce functional responses. Hence in vitro growth inhibition and transmission blocking assays were performed on Day 42 sera from mice immunized with AMA1-rEPA and Pfs25-rEPA, respectively. When purified IgGs isolated from mouse serum pools of AMA1 and AMA1-rEPA conjugates were tested against FVO P. falciparum parasites, in vitro inhibition invasion of erythrocytes was observed. As previously reported, a strong correlation between growth inhibition activity and anti-AMA1 IgG level was also observed. Likewise, when serum pools from mice immunized with Pfs25-rEPA conjugates were tested for their ability to inhibit the growth of parasites in the mosquito midgut, almost 100% reduction in oocyst numbers was observed.

The present study demonstrates the value of conjugation of malarial antigens to rEPA to improve antibody titers. Conjugation induced a remarkable increase in antibody titer for Pfs25 that was a poor immunogen on Alhydrogel in mice. Unlike Pfs25, AMA1 on Alhydrogel was a good immunogen in mice and conjugation to rEPA significantly increase the antibody titer. Unlike the findings in mice, AMA1 on Alhydrogel is a poor immunogen in human volunteer studies. The marked increase in immunogenicity to a poor immunogen in mice (Pfs25) justifies vaccine trials in humans where a similar increase in immunogenicity with AMA1-rEPA may occur.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NIAID.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Barr TA, Carlring J, Heath AW. Co-stimulatory agonists as immunological adjuvants. Vaccine. 2006;24(17):3399–407. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hunter RL. Overview of vaccine adjuvants: present and future. Vaccine. 2002;20 (Suppl 3):S7–12. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00164-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pink JR, Kieny MP. 4th meeting on Novel Adjuvants Currently in/close to Human Clinical Testing World Health Organization -- organisation Mondiale de la Sante Fondation Merieux, Annecy, France, 23–25, June 2003. Vaccine. 2004;22(17–18):2097–102. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burrage M, Robinson A, Borrow R, Andrews N, Southern J, Findlow J, et al. Effect of vaccination with carrier protein on response to meningococcal C conjugate vaccines and value of different immunoassays as predictors of protection. Infect Immun. 2002;70(9):4946–54. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.9.4946-4954.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huebner RE, Nicol M, Mothupi R, Kayhty H, Mbelle N, Khomo E, et al. Dose response of CRM197 and tetanus toxoid-conjugated Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccines. Vaccine. 2004;23(6):802–6. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kantor E, Luxenberg JS, Lucas AH, Granoff DM. Phase I study of the immunogenicity and safety of conjugated Hemophilus influenzae type b vaccines in the elderly. Vaccine. 1997;15(2):129–32. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(96)00164-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zangwill KM, Greenberg DP, Chiu CY, Mendelman P, Wong VK, Chang SJ, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in infants. Vaccine. 2003;21(17–18):1894–900. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(03)00013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lagos R, Valenzuela MT, Levine OS, Losonsky GA, Erazo A, Wasserman SS, et al. Economisation of vaccination against Haemophilus influenzae type b: a randomised trial of immunogenicity of fractional-dose and two-dose regimens. Lancet. 1998;351(9114):1472–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)07456-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johansson HJ, Jagersten C, Shiloach J. Large scale recovery and purification of periplasmic recombinant protein from E. coli using expanded bed adsorption chromatography followed by new ion exchange media. J Biotechnol. 1996;48(1–2):9–14. doi: 10.1016/0168-1656(96)01390-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mai NL, Phan VB, Vo AH, Tran CT, Lin FY, Bryla DA, et al. Persistent efficacy of Vi conjugate vaccine against typhoid fever in young children. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(14):1390–1. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200310023491423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin FY, Ho VA, Khiem HB, Trach DD, Bay PV, Thanh TC, et al. The efficacy of a Salmonella typhi Vi conjugate vaccine in two-to-five-year-old children. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(17):1263–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104263441701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eriksson K, Fredriksson M, Nordstrom I, Holmgren J. Cholera toxin and its B subunit promote dendritic cell vaccination with different influences on Th1 and Th2 development. Infect Immun. 2003;71(4):1740–7. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.4.1740-1747.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iglesias E, Aguilar JC, Cruz LJ, Reyes O. Broader cross-reactivity after conjugation of V3 based multiple antigen peptides to HBsAg. Mol Immunol. 2005;42(1):99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joyce J, Cook J, Chabot D, Hepler R, Shoop W, Xu Q, et al. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of Bacillus anthracis poly-gamma-D-glutamic acid capsule covalently coupled to a protein carrier using a novel triazine-based conjugation strategy. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(8):4831–43. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509432200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kubler-Kielb J, Liu TY, Mocca C, Majadly F, Robbins JB, Schneerson R. Additional conjugation methods and immunogenicity of Bacillus anthracis poly-gamma-D-glutamic acid-protein conjugates. Infect Immun. 2006;74(8):4744–9. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00315-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stanisic DI, Martin LB, Liu XQ, Jackson D, Cooper J, Good MF. Analysis of immunological nonresponsiveness to the 19-kilodalton fragment of merozoite surface Protein 1 of Plasmodium yoelii: rescue by chemical conjugation to diphtheria toxoid (DT) and enhancement of immunogenicity by prior DT vaccination. Infect Immun. 2003;71(10):5700–13. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.10.5700-5713.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Que JU, Cryz SJ, Jr, Ballou R, Furer E, Gross M, Young J, et al. Effect of carrier selection on immunogenicity of protein conjugate vaccines against Plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoites. Infect Immun. 1988;56(10):2645–9. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.10.2645-2649.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kubler-Kielb J, Majadly F, Wu Y, Narum DL, Guo C, Miller LH, et al. Long-lasting and transmission-blocking activity of antibodies to Plasmodium falciparum elicited in mice by protein conjugates of Pfs25. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(1):293–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609885104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alonso PL, Sacarlal J, Aponte JJ, Leach A, Macete E, Aide P, et al. Duration of protection with RTS,S/AS02A malaria vaccine in prevention of Plasmodium falciparum disease in Mozambican children: single-blind extended follow-up of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366(9502):2012–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67669-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malkin EM, Diemert DJ, McArthur JH, Perreault JR, Miles AP, Giersing BK, et al. Phase 1 clinical trial of apical membrane antigen 1: an asexual blood-stage vaccine for Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Infect Immun. 2005;73(6):3677–85. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.6.3677-3685.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saul A, Lawrence G, Allworth A, Elliott S, Anderson K, Rzepczyk C, et al. A human phase 1 vaccine clinical trial of the Plasmodium falciparum malaria vaccine candidate apical membrane antigen 1 in Montanide ISA720 adjuvant. Vaccine. 2005;23(23):3076–83. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stoute JA, Gombe J, Withers MR, Siangla J, McKinney D, Onyango M, et al. Phase 1 randomized double-blind safety and immunogenicity trial of Plasmodium falciparum malaria merozoite surface protein FMP1 vaccine, adjuvanted with AS02A, in adults in western Kenya. Vaccine. 2005 doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malkin EM, Durbin AP, Diemert DJ, Sattabongkot J, Wu Y, Miura K, et al. Phase 1 vaccine trial of Pvs25H: a transmission blocking vaccine for Plasmodium vivax malaria. Vaccine. 2005;23(24):3131–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Narum DL, Thomas AW. Differential localization of full-length and processed forms of PF83/AMA-1 an apical membrane antigen of Plasmodium falciparum merozoites. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1994;67(1):59–68. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(94)90096-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peterson MG, Marshall VM, Smythe JA, Crewther PE, Lew A, Silva A, et al. Integral membrane protein located in the apical complex of Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9(7):3151–4. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.7.3151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaslow DC, Quakyi IA, Syin C, Raum MG, Keister DB, Coligan JE, et al. A vaccine candidate from the sexual stage of human malaria that contains EGF-like domains. Nature. 1988;333(6168):74–6. doi: 10.1038/333074a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fass R, van de Walle M, Shiloach A, Joslyn A, Kaufman J, Shiloach J. Use of high density cultures of Escherichia coli for high level production of recombinant Pseudomonas aeruginosa exotoxin A. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1991;36(1):65–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00164700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shimp RL, Jr, Martin LB, Zhang Y, Henderson BS, Duggan P, Macdonald NJ, et al. Production and characterization of clinical grade Escherichia coli derived Plasmodium falciparum 42kDa merozoite surface protein 1 (MSP1(42)) in the absence of an affinity tag. Protein Expr Purif. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2006.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ellman GL. Tissue sulfhydryl groups. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1959;82(1):70–7. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(59)90090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kennedy MC, Wang J, Zhang Y, Miles AP, Chitsaz F, Saul A, et al. In vitro studies with recombinant Plasmodium falciparum apical membrane antigen 1 (AMA1): production and activity of an AMA1 vaccine and generation of a multiallelic response. Infect Immun. 2002;70(12):6948–60. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.12.6948-6960.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsai CW, Duggan PF, Shimp RL, Jr, Miller LH, Narum DL. Overproduction of Pichia pastoris or Plasmodium falciparum protein disulfide isomerase affects expression, folding and O-linked glycosylation of a malaria vaccine candidate expressed in P. pastoris. J Biotechnol. 2006;121(4):458–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2005.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shuler KR, Dunham RG, Kanda P. A simplified method for determination of peptide-protein molar ratios using amino acid analysis. J Immunol Methods. 1992;156(2):137–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(92)90020-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kocken CH, van der Wel AM, Dubbeld MA, Narum DL, van de Rijke FM, van Gemert GJ, et al. Precise timing of expression of a Plasmodium falciparum-derived transgene in Plasmodium berghei is a critical determinant of subsequent subcellular localization. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(24):15119–24. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.24.15119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaslow DC, Bathurst IC, Lensen T, Ponnudurai T, Barr PJ, Keister DB. Saccharomyces cerevisiae recombinant Pfs25 adsorbed to alum elicits antibodies that block transmission of Plasmodium falciparum. Infect Immun. 1994;62(12):5576–80. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.12.5576-5580.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Folta-Stogniew E, Williams KR. Determination of molecular masses of proteins in solution: Implementation of an HPLC size exclusion chromatography and laser light scattering service in a core laboratory. J Biomol Tech. 1999;10(2):51–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mullen GE, Giersing BK, Ajose-Popoola O, Davis HL, Kothe C, Zhou H, et al. Enhancement of functional antibody responses to AMA1-C1/Alhydrogel, a Plasmodium falciparum malaria vaccine, with CpG oligodeoxynucleotide. Vaccine. 2006;24(14):2497–505. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Singh S, Miura K, Zhou H, Muratova O, Keegan B, Miles A, et al. Immunity to recombinant Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein 1 (MSP1): protection in Aotus nancymai monkeys strongly correlates with anti-MSP1 antibody titer and in vitro parasite-inhibitory activity. Infect Immun. 2006;74(8):4573–80. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01679-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu Y, Przysiecki C, Flanagan E, Bello-Irizarry SN, Ionescu R, Muratova O, et al. Sustained high antibody responses induced by conjugation of a poor protein immunogen to OMPC for malarial vaccine development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(48):18243–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608545103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Quakyi IA, Carter R, Rener J, Kumar N, Good MF, Miller LH. The 230-kDa gamete surface protein of Plasmodium falciparum is also a target for transmission-blocking antibodies. J Immunol. 1987;139(12):4213–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fattom A, Schneerson R, Watson DC, Karakawa WW, Fitzgerald D, Pastan I, et al. Laboratory and clinical evaluation of conjugate vaccines composed of Staphylococcus aureus type 5 and type 8 capsular polysaccharides bound to Pseudomonas aeruginosa recombinant exoprotein A. Infect Immun. 1993;61(3):1023–32. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.3.1023-1032.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dagan R, Eskola J, Leclerc C, Leroy O. Reduced response to multiple vaccines sharing common protein epitopes that are administered simultaneously to infants. Infect Immun. 1998;66(5):2093–8. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.2093-2098.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dutta S, Lalitha PV, Ware LA, Barbosa A, Moch JK, Vassell MA, et al. Purification, characterization, and immunogenicity of the refolded ectodomain of the Plasmodium falciparum apical membrane antigen 1 expressed in Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 2002;70(6):3101–10. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.6.3101-3110.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hodder AN, Crewther PE, Anders RF. Specificity of the protective antibody response to apical membrane antigen 1. Infect Immun. 2001;69(5):3286–94. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.5.3286-3294.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zou L, Miles AP, Wang J, Stowers AW. Expression of malaria transmission-blocking vaccine antigen Pfs25 in Pichia pastoris for use in human clinical trials. Vaccine. 2003;21(15):1650–7. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00701-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]