Summary

The SUMO E2 Ubc9 serves as a lynchpin in the SUMO conjugation pathway, interacting with the SUMO E1 during activation, with thioester linked SUMO after E1 transfer and with the substrate and SUMO E3 ligases during conjugation. In this manuscript, we describe the structure determination of a non-covalent complex between human Ubc9 and SUMO-1 at 2.4 Å resolution. Non-covalent interactions between Ubc9 and SUMO are conserved in human and yeast insomuch as human Ubc9 interacts with each of the human SUMO isoforms, and yeast Ubc9 interacts with Smt3, the yeast SUMO ortholog. Structural comparisons reveal similarities to several other non-covalent complexes in the ubiquitin pathway, suggesting that the non-covalent Ubc9-SUMO interface may be important for poly-SUMO chain formation, for E2 recruitment to SUMO conjugated substrates, or for mediating E2 interactions with either E1 or E3 ligases. Biochemical analysis suggests this surface is less important for E1 activation or di-SUMO-2 formation, but more important for E3 interactions and for poly-SUMO chain formation when the chain exceeds more than two SUMO proteins.

Keywords: X-ray structure, SUMO, Ubiquitin-like, conjugation, Smt3, Ubc9

Introduction

Ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like proteins (Ub/Ubl) regulate a variety of cellular pathways including apoptosis, differentiation, development, responses to stress, and the cell cycle.1 Most Ub/Ubl family members are 8–11 kDa proteins, and many can be conjugated to target proteins via an ε-linked isopeptide bond between the Ub/Ubl C-terminus and a lysine of the protein target.2–4 Ub/Ubls can also serve as substrates for conjugation to form Ub/Ubl chains with varying topology. Lys48 linked polyubiquitin chains are perhaps the best characterized, although other chain topologies exist that do not target proteins for degradation via the 26S proteasome.2

In addition to ubiquitin, at least ten other ubiquitin-like modifiers that share structural similarity to ubiquitin have been uncovered in recent years.5 Of these, SUMO (Smt3 in yeast) is the most extensively characterized with at least 100 different cellular targets identified in a variety of organisms.6–9 As with ubiquitin, SUMO appears to be involved in not one, but numerous cellular processes including nuclear transport, chromosome segregation and transcriptional regulation among others.10 The SUMO pathway differs from ubiquitin insomuch as mammals contain at least four SUMO family members, SUMO-1 to -4. SUMO-2 and SUMO-3 share 43% and 42% identity to SUMO-1, respectively. SUMO-2 and SUMO-3 are highly related and share greater than 96% sequence identity to each other in their processed forms. SUMO-4 is more similar to SUMO-2/3, but it remains unclear whether SUMO-4 forms SUMO conjugates in vivo.11 SUMO-2 and SUMO-3, and the yeast SUMO Smt3, can form polymeric chains in vitro and in vivo, primarily via conjugation to lysine residues located within SUMO consensus modification sites near the SUMO N-terminus.12–15 Although the significance of SUMO-2/3 chains remains uncertain, polymeric Smt3 chains may play a functional role during meiotic chromosomal segregation in yeast.16

Ub/Ubl proteins are synthesized as precursors, and are processed by proteases to their mature form. These enzymes release residues at the Ub/Ubl C-terminus to expose a conserved C-terminal Gly-Gly motif which is then adenylated in an ATP-dependent process by an E1-activating enzyme. The adenylated Ub/Ubl C-terminus is transferred to an intramolecular E1-Ub/Ubl thioester linkage, eliminating AMP and facilitating lateral exchange with an E2-conjugating protein to yield an E2-Ub/Ubl thioester. In some cases, the E2-Ub/Ubl-thioester can directly conjugate the Ub/Ubl to a lysine on the protein target, but more frequently E3 Ub/Ubl ligases are required to facilitate Ub/Ubl conjugation to target proteins. As such, E2 proteins represent a critical node in the pathway since they are required to interact with E1, Ub/Ubl, substrates, and E3 ligases.

Perhaps it is not surprising that in addition to these functions, another E2 surface has been implicated in non-covalent interactions with ubiquitin as illustrated by complexes observed between Ub-UbcH5,17 Ub-Ubc2,18 Nedd8-Ubc4,19 and Ub-Mms2, an E2-related UEV protein.20 Of these, interactions between UbcH5 and ubiquitin were shown to be important for polyubiquitin chain formation, the complex between Mms2 and ubiquitin was shown to be important for specifying K63-linked topology during Ub polymerization, and the Nedd8 interactions with Ubc4 are thought to play a role in recruitment of the charged E2 to the Nedd8 conjugated SCF complex. Intriguingly, characterization of a non-covalent complex between SUMO and the SUMO E2 Ubc9 by NMR chemical shift perturbations also identified similar surface interactions between Ubc9 and SUMO,21 and while mutations in the observed interface were reported to alter the ability of the E2 to be charged by E121, the functional significance of this observation has remained unclear.12

To provide additional insights into this non-covalent E2-SUMO interaction, and to probe its functional significance, we report the crystal structure of a complex between human Ubc9 and SUMO-1, and provide structural and biochemical evidence that this surface is conserved among known SUMO isoforms. Characterization of Ubc9 and mutant Ubc9 isoforms revealed differing activities in biochemical assays for E2-thioester formation, di-SUMO chain formation, and formation of extended poly-SUMO chains.

Results and discussion

Structure of human Ubc9 in complex with SUMO-1

Full-length H. sapiens Ubc9 and full-length mature SUMO-1 were generated as described previously.22,23 The resulting complex was purified by gel filtration, concentrated and crystallized (Table 1). The Ubc9-SUMO-1 structure was determined by molecular replacement using the structure of human Ubc9.22,24 SUMO-1 was manually docked into the resulting electron density. The polypeptide chain of human Ubc9 can be clearly observed in the electron density from amino acid 1 to 158, including three additional N-terminal residues left after removal of the thrombin cleavable hexahistidine tag (Figures 1). The SUMO-1 molecule is well-defined from amino acid residues 21 to 94, although the respective N- and C-terminal extensions were disordered (1–20 and 95–97) and could not be assigned in the electron density maps. Only one interface exists between Ubc9 and SUMO-1 in the crystal lattice, thus definitively identifying the interaction surface within the structure (Supplemental Figure 1). The final model contains one Ubc9-SUMO-1 complex per asymmetric unit and was refined at 2.4 Å resolution to a final R-factor and R free of 0.225 and 0.250, respectively (Table I).

Table I.

Crystallographic Data

| Data Collection | Refinement Statistics | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| PDB ID | XXXX | Resolution (Å) | 20-2.4 (2.49-2.4) |

| Source | APS 24ID | Number of reflections | 11127 (1128) |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9795 | Completeness (%) | 96.7 (92.8) |

| Resolution (Å) | 50-2.4 (2.49-2.4) | Cutoff Criteria I/σI | 0 |

| Space Group | P21212 | # Atoms (protein/water) | 1894/67 |

| Unit Cell (Å) | a=86.7, b=38.6, c=83.4 | Rcrystb | 0.225 (0.324) |

| # of observations | 58005 | Rfree (5% of data) | 0.250 (0.341) |

| # of reflections | 11142 (1039) | r.m.s.d. bonds (Å)/angles (°) | 0.006/1.10 |

| Completeness (%) | 96.5 (92.7) | Average B factor (Ubc9:SUMO:water) | 47.8:107.8:49.1 |

| Redundancy | 5.2 (3.1) | ||

| Mean I/σI | 20.8 (2.9) | ||

| R-merge on Ia | 0.059 (0.338) | ||

| Cut-off criteria I/σI | 0 |

Rmerge = Σhkl Σi|I(hkl)i - <I(hkl)>|/ΣhklΣi <I(hkl)i>.

Rcryst = Σhkl |Fo(hkl)-Fc(hkl)|/Σhkl |Fo(hkl)|, where Fo and Fc are observed and calculated structure factors, respectively.

Data in parentheses indicate statistics for data in the highest resolution bin. 25 mg of purified Ubc9 was combined with 20 mg of purified full-length mature SUMO-1 in 10 mL of 20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 350 mM NaCl, and 1 mM BME, and dialyzed overnight at 4°C against 1 L of low salt buffer (20mM Tris pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, and 1 mM BME). E2-SUMO complex was then resolved on a Superdex75 gel filtration column equilibrated with low salt buffer. Fractions containing the non-covalent complex were pooled and concentrated to 10 mg/mL, flash frozen with liquid nitrogen, then stored at −80°C. Crystallization was performed at 4 °C using sitting and hanging drop vapour diffusion method. The reservoir solution contained 100 mM Tris pH 8.5, 25% PEG 3000. Single crystals were grown after 7 days from equal volumes of protein solution (10 mg/ml in 20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM BME) and of reservoir solution. Prior to diffraction, crystals were cryo-protected in reservoir buffer containing 12% glycerol and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Diffraction data were recorded from 100K-cryocooled crystals at the NE-CAT 24ID at the Advance Photon Source (Argonne, Chicago, Ill). Data were integrated, scaled and merged using DENZO and SCALEPACK. 38 The crystals contain one protein complex per asymmetric unit. The structure was solved by molecular replacement with Ubc9 (pdb 1KPS) as a search model using MOLREP (CCP4). 24 Afterwards, a search model (SUMO-1 structure) was manually docked into experimental density and rebuilt using the program O. 39 Refinement was performed with CNS. 31 Defined amino acid residues exhibit main chain angles falling into the most favored (88 %) or additional favored regions (12 %) of the Ramachandran plot.40

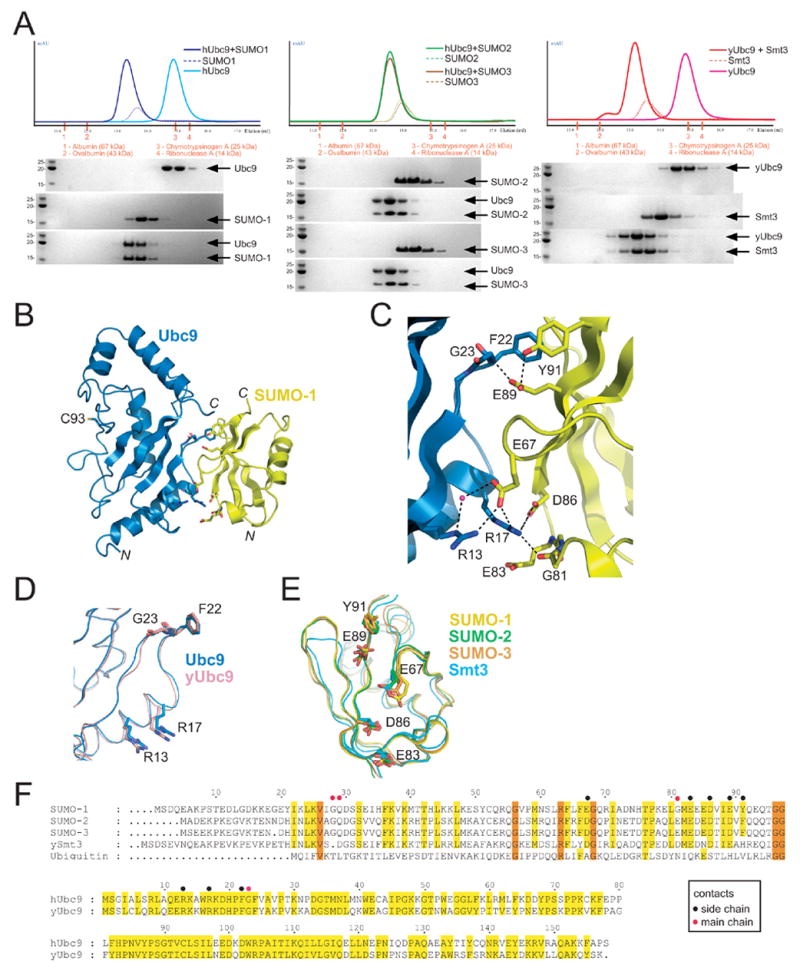

Figure 1. Characterization of the Ubc9-SUMO interaction.

(A) Gel filtration analysis for interactions between human Ubc9 and SUMO-1 (left), human Ubc9 and either SUMO-2 or SUMO-3 (middle), or yeast Ubc9 and Smt3 (right). UV chromatograms are shown in the top panel, color coded for the particular protein in question. SDS-PAGE analysis for the resulting fractions stained with Coomassie Blue with indicated proteins labeled on the right. Apparent molecular weight markers and indicated molecular weights are shown to the left of each gel inset. The elution volume and gel filtration molecular weight standards are indicated for each panel. (B) Ribbon representation of the Ubc9-SUMO-1 structure with Ubc9 in blue and SUMO-1 in yellow. The Ubc9 catalytic cysteine is labeled (C93). Respective N- and C-termini are labeled. All graphics prepared using PYMOL.41 (C) Close-up of the Ubc9-SUMO-1 interface with residues labeled and shown in stick representation. Dashed lines indicate potential hydrogen bond interactions. (D) Superposition of human and yeast Ubc9 (PDB 2GJD) highlighting the conserved residues involved in the interaction with SUMO-1 color coded and labeled. (E) Superposition of human SUMO-1, SUMO-2 (PDB 2IO0), SUMO-3 (PDB 2IO1) and yeast Smt3 (PDB 1EUV) highlighting the conserved residues involved in the interaction with Ubc9 color coded and labeled. (F) Sequence alignment for SUMO and Ubc9 isoforms. Top panel includes alignment of human SUMO isoforms, yeast Smt3, and human ubiquitin. Amino acid numbering for SUMO-1 is shown above the alignment. Conserved residues shaded yellow, identical residues shaded orange. The bottom panel includes an alignment between yeast and human Ubc9 with similar and identical residues shaded yellow. Amino acid numbering is shown above the alignment. Black or red dots above either alignment indicate side chain or main chain contacts, respectively. Recombinant human Ubc9, SUMO-1, SUMO-2, SUMO-3, yeast Ubc9 and yeast Smt3 were prepared as previously described.22,23,25 Gel filtration was performed with an analytical Superose 12 column (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences) using individual proteins at 100 μM and complexes at equimolar concentrations (100 μM). 200 μL were injected in each case and fractions analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining. The buffer used for Ubc9 and SUMO-1/2/3 analysis consisted of 20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM βME. The buffer used for yeast Ubc9 and yeast Smt3 consisted of 20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM βME.

Comparison of SUMO-1 in our structure with other crystal structures of SUMO in complex with the SUMO E1,25 with the SUMO protease Senp2,23,26 or in the context of a complex containing Ubc9, SUMO conjugated RanGAP1, and a RanBP2/Nup358 E3 domain27 revealed that SUMO-1 does not undergo large conformational changes upon binding Ubc9 in this complex (Figures 1E and 2). The only conformational difference observed was for the SUMO-1 C-terminal tail insomuch as the C-terminal amino acids were ordered in previous structures, but were not observed in the present structure past amino acid 94. The Ubc9 structure also resembles those previously determined, either alone,28,29 in complex with RanGAP1,22,30 or in complex with SUMO conjugated RanGAP1 and a RanBP2/Nup358 E3 domain.27 The E2 active site is located on the opposite surface from that involved in non-covalent interactions with SUMO-1 and is configured similarly to that observed in previous structures (Figure 1).

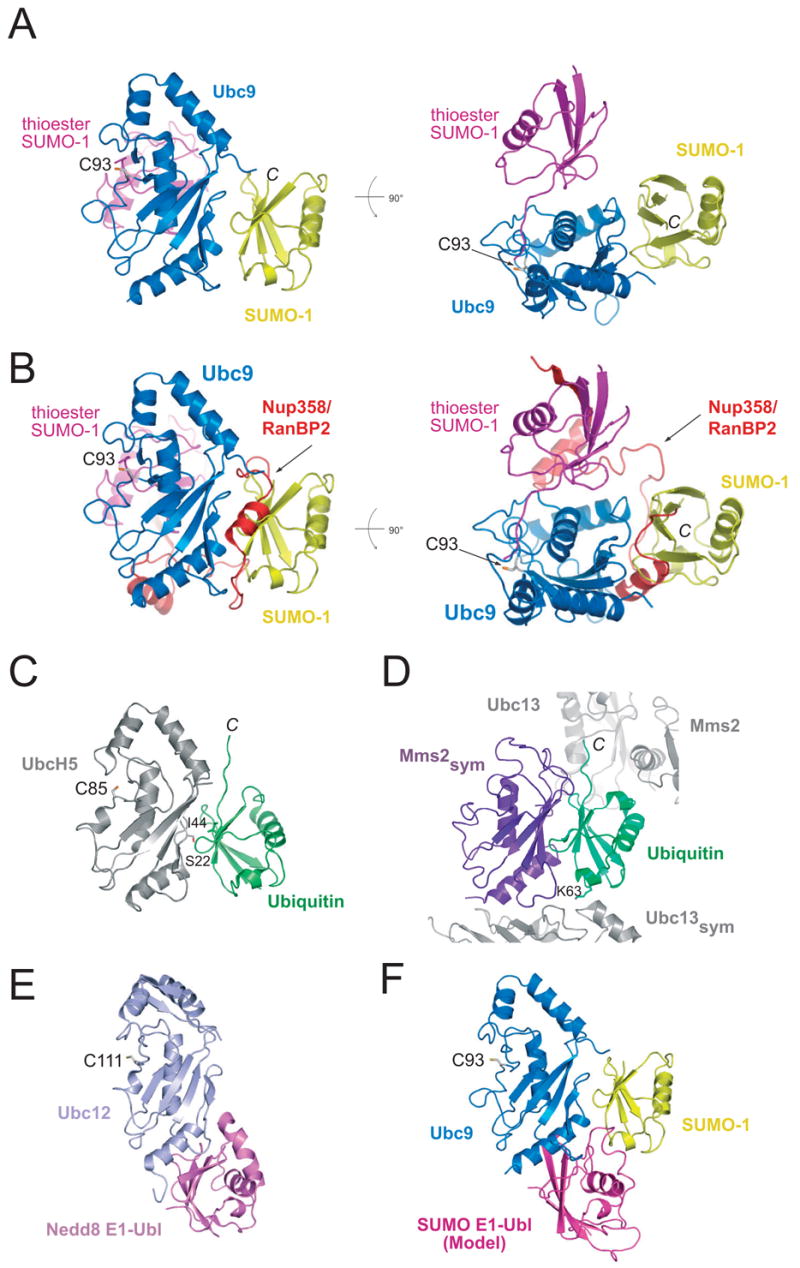

Figure 2. Structural comparisons between Ubc9-SUMO-1 and other E2 complexes.

In each instance, the respective E2 molecules were superimposed to generate the resulting composite models. (A) Two orientations of the non-covalent Ubc9-SUMO-1 complex (blue and yellow) in which the SUMO-1 molecule (magenta) from the SUMO-1-RanGAP1/Ubc9/Nup358 structure (PDB 1Z5S) was modeled to illustrate differences in respective SUMO conformations. (B) Two orientations of the same comparison to panel A in which the Nup358/RanBP2 E3 is included to illustrate the overlap between the non-covalent SUMO interaction and a domain within the E3. (C) Structure of the UbcH5-ubiquitin non-covalent complex (PDB 2FUH). (D) Structure of the non-covalent interaction between Mms2 and ubiquitin (PDB 2GMI). (E) Structure of the Ubc12 interaction with the Nedd8 E1 ubiquitin-like domain (PDB 1Y8X). (F) Model of the SUMO E1 ubiquitin-like domain in complex with the non-covalent complex between Ubc9-SUMO-1 to illustrate that the two interactions may partially overlap.

The Ubc9-SUMO-1 interface

The Ubc9-SUMO-1 interface covers a continuous surface, burying 1100 Å2 of total buried surface area in the complex as calculated by CNS.31 The interaction surface involves residues emanating from the exposed SUMO β-sheet, and overlaps substantially with SUMO surfaces used for interactions with its E1, proteases, or E2 within a conjugated substrate E3 complex.23, 25–27 The properties of those amino acid residues involved in the Ubc9-SUMO-1 interaction are mixed, and include both polar and non-polar contacts (Figure 1C). The Ubc9 Arg13 side chain contacts the side chain carboxylate of SUMO-1 Glu67 directly and through a water mediated hydrogen bond. The Ubc9 Arg17 side chain contacts the SUMO-1 Gly81 carbonyl oxygen, and also makes two salt bridging interactions with the side chain carboxylates from SUMO Glu67 and Asp86. SUMO-1 Glu83 is proximal to the Arg17 side chain, but makes no direct contacts. On the other side of the interface, contacts are observed between the Ubc9 Gly23 amide nitrogen and SUMO-1 Glu89 carboxylate. In addition, Ubc9 Phe22 makes several Van der Waals interactions with the SUMO-1 surface, including interactions with the Tyr91 and Glu89 side chains and Phe22 side chain contacts with backbone atoms from SUMO-1 Gly28 and Gln29.

Both SUMO C-terminal and N-terminal regions are disordered in the Ubc9-SUMO-1 complex, and would thus be free for interactions with other partners. However neither N- nor C-terminal extensions are long enough to reach the E2 catalytic cysteine, suggesting that the observed conformation would not be possible if the C-terminal glycine were linked to the E2 cysteine, or if the N-terminal SUMO consensus conjugation site (in SUMO-2 or SUMO-3) were coordinated in the E2 substrate binding surface. It is worth noting that SUMO surfaces implicated in non-covalent interactions with SUMO interaction motifs (SIMs) are fully exposed in our complex, suggesting that the non-covalent complex would not preclude interactions with molecules containing SIM elements.27,32–33

Sequence alignments and structural comparisons suggested that residues involved in intermolecular Ubc9-SUMO-1 contacts are highly conserved in both human and yeast, either for Ubc9 or for SUMO isoforms in human (SUMO-1/2/3) and Smt3 in yeast (Figure 1F). The conservation in the interface led us to explore whether human Ubc9 could form equivalent complexes with SUMO-2/3, or whether yeast Ubc9 could form an analogous complex with the yeast SUMO ortholog Smt3. We employed gel filtration and SDS-PAGE analysis to analyze each of the aforementioned complexes (Figure 1A). Human Ubc9 formed stochiometric complexes with either SUMO-1 or SUMO-2/3 by gel filtration analysis (Figure 1A), consistent with the conservation of interfacial residues observed in our crystal structure (Figure 1D–F). These complexes migrated with an apparent molecular weight of 30–35 kDa, consistent with the complex containing one copy of Ubc9 and one copy of the respective SUMO isoform. Yeast Ubc9 also formed a stochiometric complex with Smt3 as analyzed by gel filtration and SDS-PAGE (Figure 1A), eluting with an apparent molecular weight of 35 kDa consistent with that observed for the human proteins (1:1 complex). Taken together, these data suggest that the surfaces observed for Ubc9 and SUMO isoforms are evolutionarily conserved, and each contributes to formation of a stable complex between Ubc9 and SUMO using either yeast or human proteins (Figures 1).

These results are consistent with those reported previously for human Ubc9 and SUMO-1, SUMO-2, and SUMO-3 as determined by NMR chemical shift perturbations and isothermal titration calorimetry.21,34 In NMR studies, it was determined that interactions were mediated between the exposed SUMO β-sheet and an N-terminal site within Ubc9. Specifically, twenty SUMO-1 residues (27–32, 38, 63–71, and 82–90) exhibited chemical shift perturbations upon titration with Ubc9. In our crystal structure, interactions are only observed with eleven SUMO-1 residues (25, 28, 29, 63, 67, 81, 83, 86, 87, 89, and 91; < 3.6 Å cutoff). NMR studies also identified 25 Ubc9 surface residues that exhibited chemical shift perturbations upon SUMO binding, including Ubc9 residues 15, 17–19, 23, and 26, and to lesser extent, Ubc9 residues 7, 10, 14, 20, 22, 27, 35, 37, 44, 49, 60, 62, 63, 99, 109, 110, 112, 113, and 158. In our structure, only seven Ubc9 residues 13, 17, 18, 22, 23 27, and 49 make direct contacts to SUMO-1 (< 3.6 Å cutoff).

Comparison to other E2-Ub structures

It is instructive to compare the non-covalent Ubc9 and SUMO-1 complex to the structure of Ubc9 in complex with RanGAP1 or with SUMO conjugated RanGAP1 and the SUMO E3 RanBP2/Nup358.22,27,30 In these structures, Ubc9 interacts with the substrate RanGAP1 through a similar interface, and comparisons to the non-covalent Ubc9-SUMO-1 complex revealed no overlap between the substrate binding surface and non-covalent SUMO interaction surface (not shown). In the E2/E3/substrate-SUMO complex, SUMO was observed interacting with the E2 active site and an E2 helix (Figure 2A). Because the conjugated lysine (not shown) and C-terminal SUMO glycine residue remained proximal to the E2 catalytic cysteine, we suggested that this conformation approximated that for the thioester-linked SUMO in its activated state (prior to conjugation). This activated SUMO conformation does not overlap with the non-covalent SUMO binding surface (Figure 2A), suggesting that Ubc9 can interact simultaneously with both an activated thioester-linked SUMO and another SUMO via the non-covalent surface. In contrast, analysis of the E2/E3/SUMO-substrate complex reveals that C-terminal domains within the RanBP2/Nup358 E3 ligase would overlap with surfaces involved in the non-covalent SUMO interaction (Figure 2B), suggesting that the non-covalent complex could interfere with E2–E3 interactions.27

The interactions between Ubc9 and SUMO-1 in the non-covalent complex resemble those observed in other non-covalent complexes in the ubiquitin pathway, namely ubiquitin interactions with the E2 UbcH5 or with the UEV domain Mms2 (Figure 2C and D).17,20 The non-covalent complex between UbcH5 and ubiquitin was proposed to facilitate polyubiquitin chain formation insomuch as mutation at UbcH5 Ser22 abolished the non-covalent interaction with ubiquitin and disrupted the ability of UbcH5 to catalyze BRCA1 directed polyubiquitin chain elongation.17 The Mms2 UEV domain makes analogous contacts to ubiquitin, albeit in a complex which contains ester linked Ubc13-ubiquitin and Mms2. In this instance, Mms2 interactions with ubiquitin serve to direct the ubiquitin Lys63 side chain into the Ubc13 active site. Disruption of the Mms2-ubiqutin interface leads to severe reduction in the ability of the Ubc13/Mms2 heterodimer to catalyze formation of Lys63-linked polyubiquitin chains.20,35 Interestingly, similar interactions have also been observed for Ubc2b and ubiquitin18 and for Ubc4 and Nedd8,19 the latter is thought to recruit ubiquitin E2s to Nedd8 conjugated SCF complexes.

While the above interactions are associated with particular functions in ubiquitin conjugation or chain formation, it remains unclear as to why this interface is conserved in the SUMO pathway. Previous mutational and biochemical analysis suggested that mutations within this interface, namely Ubc9 R13A/K14A and R17A/K18A, did not alter E2-substrate or E1–E2 interactions, but did alter the ability of the E2 to be charged by the E1.34 However, more recent structural analyses of the Nedd8 E1 and Nedd8 E1 ubiquitin-like domain in complex with Ubc12 (Figure 2E),36,37 and modeling of the SUMO E1 ubiquitin-like domain in complex with Ubc9 and SUMO-1 suggest that the E1 and non-covalent SUMO interactions would not substantially overlap (Figure 2F). Consistent with this model, our previous data suggest that the SUMO E1 ubiquitin-like domain could form a complex with Ubc9 that is stable in the presence of excess SUMO-1.25

Mutational and biochemical analysis

To examined the functional consequence of the non-covalent Ubc9-SUMO-1 complex with respect to SUMO activation and poly-SUMO chain formation, we constructed several point mutations for residues on the Ubc9 surface. We did not perform mutational analysis for residues on the SUMO surface because this surface overlaps significantly with surfaces utilized in SUMO interactions with its cognate E1, Ulp/Senp protease, and with the E2 surface in its activated conformation.23,25–27 Based on the observed contacts in the non-covalent complex (Figure 1C), we selected three amino acid residues for analysis, Arg13, Arg17, and Phe22. These amino acid side chains are fully exposed on the Ubc9 surface, but participate in contacts between Ubc9 and SUMO-1 in the complex. In each instance, side chains were removed by alanine substitution; and in two cases, Arg13 and Arg17 were also replaced by glutamate side chains (Figure 1F).

To assess whether mutations on the Ubc9 surface altered the ability of Ubc9 to form stable complexes with SUMO, gel filtration and SDS-PAGE was utilized to analyze interactions between each mutant Ubc9 isoform and SUMO-2 (Figure 3A). Each Ubc9 mutant eluted from gel filtration at positions that overlapped with wild-type Ubc9, suggesting that these mutations on the Ubc9 surface do not destabilize the global fold for this protein. Analysis of Ubc9 R13A or Ubc9 R13E suggested that each failed to form complexes with SUMO-2 (Figure 3A, left). Similar results were also observed for R17A and R17E (Figure 3A, middle). In each instance, SUMO-2 and the respective Ubc9 isoform eluted at positions consistent with profiles obtained in the absence of the other protein, suggesting that these mutations nearly abolished interactions under these conditions. In contrast, when interactions between Ubc9 F22A and SUMO-2 were analyzed, gel filtration indicated that the complex migrated at an intermediate position, suggesting that F22A mutation contributed to a partial but not complete disruption of the complex (Figure 3A, right). Therefore, unlike mutations at Ubc9 Arg13 and Arg17 which completely abolished non-covalent interactions with SUMO-2 under these conditions, only a partial disruption of the non-covalent complex occurred using the F22A Ubc9 mutant.

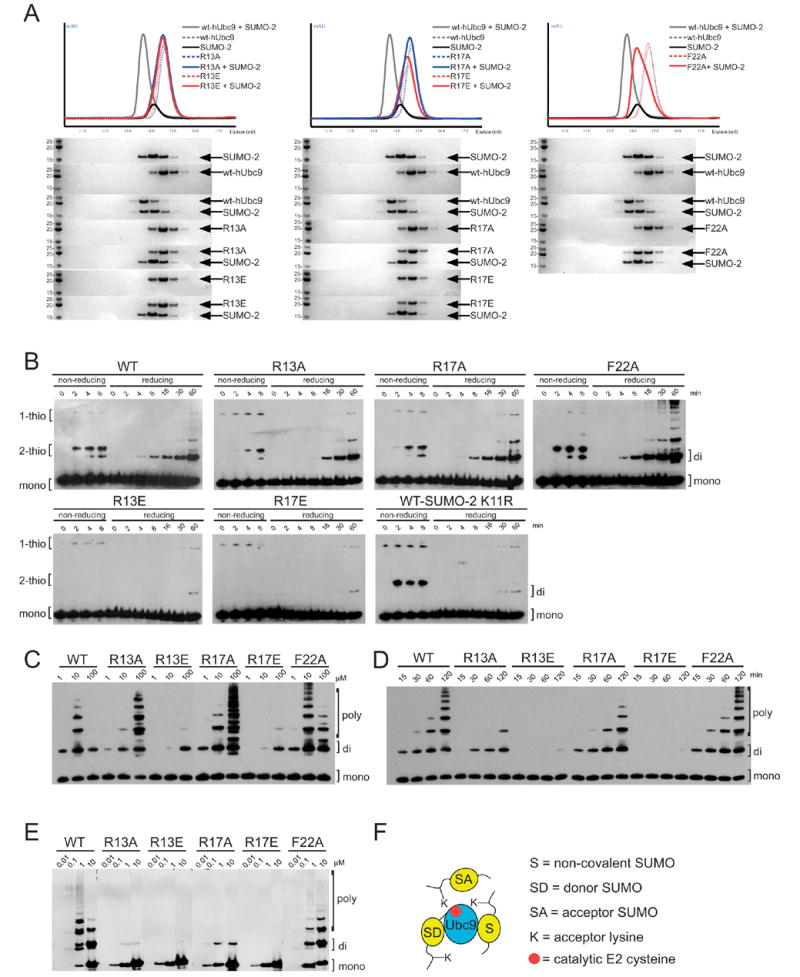

Figure 3. Biochemical and mutational analysis.

(A) Gel filtration and SDS-PAGE analysis of Ubc9 mutants to assess non-covalent complex formation with SUMO-2. R13A and R13E (left), R17A and R17E (middle), and F22A (right) were combined with equimolar quantities of SUMO-2 and analyzed by gel filtration. UV chromatograms are shown (top), color coded for the particular protein in question. SDS-PAGE analysis (bottom) for the resulting fractions stained with Coomassie Blue. Indicated proteins labeled (right) with apparent molecular weight markers and molecular weights (left). For comparison, each panel includes chromatogram profiles and SDS-PAGE analysis for wild-type Ubc9, SUMO-2, and wild-type Ubc9-SUMO-2 complex. Gel filtration was conducted similar to Figure 1A, with running buffer consisting of 20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM βME. (B) Time-course for E2-thioester formation and di-SUMO-2 conjugation for Ubc9 wild-type and mutants. Non-reducing lanes indicate formation of thioester-linked SUMO-2 to Ubc9. Reduced lanes indicate conjugated SUMO-2 species. Reactions contained 10 μM SUMO-2, 1 μM Ubc9, 100 nM E1 in reaction buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM ATP, 5 mM MgCl2, and 0.01% Tween-20) incubated at 37 °C.42 Samples were taken at indicated time points and stopped with sample loading buffer containing SDS and UREA. Reduced samples contained 100 mM BME. Samples were resolved on SDS-PAGE and blotted for SUMO-2 using SUMO-2 antibody (Invitrogen). (C) Effects of increasing concentrations of Ubc9 on the formation of di-SUMO-2 or poly-SUMO-2 conjugated chains. Reactions contained 100 μM SUMO-2, 100 nM E1, and Ubc9 concentrations ranging from 1–100 μM, in reaction buffer and incubated at 37 °C for 2 hrs. Samples were resolved on SDS-PAGE and blotted for SUMO-2. (D) Time-course for di-SUMO-2 and poly-SUMO-2 formation. Reactions containing 100 μM SUMO-2, 10 μM Ubc9, and 100 nM E1 in reaction buffer were incubated at 37 °C. Samples were taken at indicated time points, resolved on SDS-PAGE and blotted for SUMO-2. SUMO-2 species are indicated for mono-, di-, and poly-SUMO-2 forms. (E) Ability of an E3 ligase, the Nup358/RanBP2 IR1* domain, to catalyze SUMO-2 chain formation. Reactions contained 100 nM Ubc9, 100 nM E1, 400 nM IR1* domain, with SUMO-2 titrated from 10 nM – 10 μM. Samples were incubated at 37 °C in reaction buffer for 180 min, resolved on SDS-PAGE and blotted for SUMO-2. (F) Model for the interactions between Ubc9 and SUMO described in the text. The model depicts Ubc9 thioester-linked to an activated SUMO (SD for donor SUMO) in a non-covalent complex with SUMO (S) able to interact with another molecule of SUMO (SA for acceptor SUMO). This non-covalent SUMO (S) does not interfere with thioester formation or substrate binding; however, it may play a role in SUMO chain extension from a di-SUMO conjugated species.

We next tested whether mutations altered the ability of the respective Ubc9 isoforms to be activated by the SUMO E1 during formation of E2-SUMO-2 thioester adducts (Figure 3B). Alanine substitution at Phe22 did not alter E2-thioester formation, while R13A or R17A mutation only slightly diminished E2-thioester formation. For these cases, even with the disruption of the non-covalent interaction with SUMO, no substantive defects were observed during E2-mediated di-SUMO-2 chain formation under the conditions tested (Figure 3B, compare lanes under “reducing” conditions). In contrast, R13E or R17E substantially decreased E2-thioester formation, although some di-SUMO chains could be observed after 60 minutes. This suggests that removal of the positively charged side chain (as in the case for R13A or R17A) does not alter E1 interactions, while charge reversal (R13E or R17E) perturbs, but does not completely block E1 interactions. This is consistent with our structure insomuch as the non-covalent SUMO binding surface only partially overlaps with the putative SUMO E1 interaction surface (Figure 2F), and does not overlap with the activated SUMO conformation or substrate binding surface (Figure 2A).

To confirm that di-SUMO-2 chains were dependent on the N-terminal SUMO conjugation consensus site and Lys11, we analyzed reactions using the wild-type E2 in conjunction with a SUMO-2 mutant containing a K11R substitution. In this instance, thioester formation was not impeded, but chain formation was diminished in comparison to reactions containing wild-type SUMO-2 (Figure 3B). These results are consistent with a model in which the E2, thioester-linked to an activated SUMO-2 (the donor SUMO or SD), is able to interact with an incoming acceptor SUMO-2 (SA), form a di-SUMO-2 chain, regardless of whether it can associate with another molecule of SUMO via the non-covalent binding surface (S) (Figure 3F). To determine whether conjugation assays were specific for di-SUMO chains using SUMO-2 or SUMO-3 but not SUMO-1, we utilized wild-type Ubc9 in reactions to assess the ability of each SUMO isoform to form chain (Supplemental Figure 2). In these assays, only SUMO-2 and SUMO-3 were capable of forming di-SUMO chains, consistent with previous studies which demonstrated that SUMO chains were due to the presence of SUMO consensus conjugation motifs within their respective N-terminal tails.15

To further investigate the ability of each E2 isoform to catalyze di-SUMO-2 or poly-SUMO-2 chain formation, reactions were titrated with increasing concentrations of the respective E2 (Figure 3C). In this instance, we observed an inhibitory affect on SUMO-2 chain formation using wild-type Ubc9, where at 10 μM Ubc9, poly-SUMO-2 chains readily formed; while at 100 μM Ubc9, only di-SUMO-2 chains were detected. Ubc9 F22A also exhibited the inhibitory affect as observed for wild-type, although to a lesser extent. The inhibitory affect on chain formation was not observed in reactions containing either Ubc9 R13A or Ubc9 R17A since increasing E2 concentrations resulted in increased chain formation. These results are consistent with the following model. In the case of the wild-type Ubc9, excess E2 can bind and sequester SUMO-2 (or di-SUMO-2) via the non-covalent interface, either preventing activation by the E1, or preventing interactions with the activated E2-thioester SUMO. The partial inhibitory affect observed for Ubc9 F22A is consistent with the observation that this mutation did not completely abolish non-covalent SUMO-2 interactions during gel filtration (Figure 3A). However, when the non-covalent E2-SUMO-2 interaction is disrupted, as observed for R13A, R13E, R17A, or R17A (Figure 3A), these inhibitory affects are alleviated, enabling SUMO-2 and E2 activation by the E1, and/or allowing di-SUMO-2 to interact with the E2 substrate-binding surface. While Ubc9 R13E and R17E mutations exhibited a diminished ability to form di-SUMO-2 chains, the diminished activities are consistent with their reduced ability to be charged by E1 (Figure 3B).

Although each E2 mutant isoform was able to form di-SUMO-2 chains, individual mutations exhibited differences during formation of longer SUMO-2 chains (Figure 3C). The non-covalent SUMO binding surface is too far away from the E2 active site to facilitate formation of di-SUMO-2 chains through direct interaction with the N-terminal SUMO consensus modification site. However, once SUMO-2 chains are formed, the non-covalent binding surface might then serve to facilitate interactions between the E2 and the growing di-SUMO-2 chain, tethering or directing the N-terminal substrate lysine into the E2 catalytic site to promote poly-SUMO chain growth. To test whether Ubc9 mutants had increased or decreased abilities to form poly-SUMO-2 chains, we conducted an extended time course for each Ubc9 isoform (Figure 3D). Wild-type Ubc9 and F22A formed extended poly-SUMO-2 chains, while R13A or R17A had diminished activities. R13E or R17E substitution essentially abrogated chain formation beyond di-SUMO-2. The ability or lack thereof to form extended poly-SUMO-2 chains correlated well with the ability of the various mutants to interact non-covalently with SUMO-2. Therefore, this interface may play a role in facilitating SUMO chain extension.

We next determined whether mutations at Arg13, Arg17, or Phe22 altered the activities of the Nup358/RanBP2 IR1* domain, a SUMO E3 ligase, during formation of SUMO-2 chains. Mutation at Arg13 or Arg17 greatly diminished SUMO-2 chain formation, although some di-SUMO-2 could be observed in each case (Figure 3E). While F22A did not abrogate the ability to form chains, high SUMO concentrations diminished chain formation for wild-type Ubc9, but increased the chain forming activity of the F22A mutant. These results are consistent with our model where at high SUMO concentration, the non-covalent Ubc9-SUMO interface either competes for di-SUMO-2 binding, or sequesters the E2 into non-productive complexes that are less able to interact with either E1 or E3. These results are also consistent with the observation that Arg13, Arg17, and Phe22 interact with two non-essential C-terminal IR1* E3 motifs (Figure 2B),27 so it is equally possible that the inhibitory affects of chain formation are attributable to disruption of stabilizing E2–E3 interactions. Because these surfaces overlap and are mutually exclusive, it is difficult at this time to fully dissect these results with respect to the individual contributions of either E3 or SUMO in these reactions.

Conclusions

The structure of the non-covalent complex between Ubc9 and SUMO-1 reveals a conserved interface between the SUMO E2 and various SUMO isoforms. Mutations within the interface disrupted the ability of the E2 to interact with various partners in the conjugation cascade, namely SUMO, although in some instances these mutations also affected interactions with an E3 or the E1. In addition to the aforementioned interactions, it is possible that this interface could contribute to recruitment of the E2 to SUMO conjugated substrates, perhaps in conjunction with SUMO interaction motifs. Perhaps most intriguing is the observation that the non-covalent interactions between Ubc9 and SUMO-1 are reminiscent of several other non-covalent complexes between components in the ubiquitin conjugation cascade, suggesting that this E2-Ub/Ubl interaction surface is conserved in various Ub/Ubl pathways and across evolution. While it is difficult to infer functional parallels to the ubiquitin system, it is intriguing that the rather small E2 conjugating enzymes have developed so many alternative ways in which to use this interface, including that proposed for UbcH5 during polyubiquitin chain conjugation,17 for Mms2 during K63-linked polyubiquitin chain formation,20,35 or ubiquitin E2 recruitment to the Nedd8 conjugated SCF complex.19 With a similar interface now elaborated at atomic resolution within the SUMO pathway, it will remain a challenge to uncover its functional role within a biological context.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Use of the Advanced Photon Source (APS) is supported by the U.S. Dept. of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under W-31-109-Eng-38. Use of NE-CAT beamline at Sector 24 is based upon research conducted at the Northeastern Collaborative Access Team beamlines of the APS, which is supported by award RR-15301 from the NCRR at the NIH. A.D.C. and C.D.L. are supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (GM65872). A.D.C. acknowledges support from the NIH (GM075695) and C.D.L. acknowledges additional support from the Rita Allen Foundation.

Footnotes

Data Accession Codes

The atomic coordinates and x-ray structure factors will be deposited immediately upon acceptance of this manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kerscher O, Felberbaum R, Hochstrasser M. Modification of proteins by ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like proteins. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2006;22:159–80. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010605.093503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hershko A, Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin system. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:425–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hochstrasser M. There’s the rub: a novel ubiquitin-like modification linked to cell cycle regulation. Genes Dev. 1998;12:901–7. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.7.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laney JD, Hochstrasser M. Substrate targeting in the ubiquitin system. Cell. 1999;97:427–30. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80752-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwartz DC, Hochstrasser M. A superfamily of protein tags: ubiquitin, SUMO and related modifiers. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:321–8. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00113-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wohlschlegel JA, Johnson ES, Reed SI, Yates JR., 3rd Global analysis of protein sumoylation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:45662–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409203200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Panse VG, Hardeland U, Werner T, Kuster B, Hurt E. A proteome wide approach identifies sumoylated substrate proteins in yeast. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:41346–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407950200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou W, Ryan JJ, Zhou H. Global analyses of sumoylated proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Induction of protein sumoylation by cellular stresses. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:32262–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404173200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao Y, Kwon SW, Anselmo A, Kaur K, White MA. Broad spectrum identification of cellular small ubiquitin-related modifier (SUMO) substrate proteins. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:20999–1002. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401541200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Melchior F, Schergaut M, Pichler A. SUMO: ligases, isopeptidases and nuclear pores. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:612–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Owerbach D, McKay EM, Yeh ET, Gabbay KH, Bohren KM. A proline-90 residue unique to SUMO-4 prevents maturation and sumoylation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;337:517–20. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.09.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bencsath KP, Podgorski MS, Pagala VR, Slaughter CA, Schulman BA. Identification of a multifunctional binding site on Ubc9p required for Smt3p conjugation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:47938–45. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207442200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bylebyl GR, Belichenko I, Johnson ES. The SUMO isopeptidase Ulp2 prevents accumulation of SUMO chains in yeast. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:44113–20. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308357200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson ES, Gupta AA. An E3-like factor that promotes SUMO conjugation to the yeast septins. Cell. 2001;106:735–44. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00491-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tatham MH, Jaffray E, Vaughan OA, Desterro JM, Botting CH, Naismith JH, Hay RT. Polymeric chains of SUMO-2 and SUMO-3 are conjugated to protein substrates by SAE1/SAE2 and Ubc9. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:35368–74. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104214200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng CH, Lo YH, Liang SS, Ti SC, Lin FM, Yeh CH, Huang HY, Wang TF. SUMO modifications control assembly of synaptonemal complex and polycomplex in meiosis of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2067–81. doi: 10.1101/gad.1430406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brzovic PS, Lissounov A, Christensen DE, Hoyt DW, Klevit RE. A UbcH5/ubiquitin noncovalent complex is required for processive BRCA1-directed ubiquitination. Mol Cell. 2006;21:873–80. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miura T, Klaus W, Gsell B, Miyamoto C, Senn H. Characterization of the binding interface between ubiquitin and class I human ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme 2b by multidimensional heteronuclear NMR spectroscopy in solution. J Mol Biol. 1999;290:213–28. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sakata E, Yamaguchi Y, Miyauchi Y, Iwai K, Chiba T, Saeki Y, Matsuda N, Tanaka K, Kato K. Direct interactions between NEDD8 and ubiquitin E2 conjugating enzymes upregulate cullin-based E3 ligase activity. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007 doi: 10.1038/nsmb1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eddins MJ, Carlile CM, Gomez KM, Pickart CM, Wolberger C. Mms2-Ubc13 covalently bound to ubiquitin reveals the structural basis of linkage-specific polyubiquitin chain formation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:915–20. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Q, Jin C, Liao X, Shen Z, Chen DJ, Chen Y. The binding interface between an E2 (UBC9) and a ubiquitin homologue (UBL1) J Biol Chem. 1999;274:16979–87. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.24.16979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bernier-Villamor V, Sampson DA, Matunis MJ, Lima CD. Structural basis for E2 mediated SUMO conjugation revealed by a complex between ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme Ubc9 and RanGAP1. Cell. 2002;108:345–56. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00630-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reverter D, Lima CD. A Basis for SUMO Protease Specificity Provided by Analysis of Human Senp2 and a Senp2-SUMO Complex. Structure. 2004;12:1519–31. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1994;50:760–3. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lois LM, Lima CD. E1 activation of the ubiquitin-like modifier SUMO 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reverter D, Lima CD. Structural basis for SENP2 protease interactions with SUMO precursors and conjugated substrates. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:1060–8. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reverter D, Lima CD. Insights into E3 ligase activity revealed by a SUMO-RanGAP1-Ubc9-Nup358 complex. Nature. 2005;435:687–92. doi: 10.1038/nature03588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giraud MF, Desterro JM, Naismith JH. Structure of ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme 9 displays significant differences with other ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes which may reflect its specificity for sumo rather than ubiquitin. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54:891–8. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998002480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tong H, Hateboer G, Perrakis A, Bernards R, Sixma TK. Crystal structure of murine/human Ubc9 provides insight into the variability of the ubiquitin-conjugating system. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:21381–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.34.21381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yunus AA, Lima CD. Lysine activation and functional analysis of E2-mediated conjugation in the SUMO pathway. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:491–9. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brunger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, Read RJ, Rice LM, Simonson T, Warren GL. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54( Pt 5):905–21. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baba D, Maita N, Jee JG, Uchimura Y, Saitoh H, Sugasawa K, Hanaoka F, Tochio H, Hiroaki H, Shirakawa M. Crystal structure of thymine DNA glycosylase conjugated to SUMO-1. Nature. 2005;435:979–82. doi: 10.1038/nature03634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Song J, Durrin LK, Wilkinson TA, Krontiris TG, Chen Y. Identification of a SUMO-binding motif that recognizes SUMO-modified proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:14373–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403498101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tatham MH, Kim S, Yu B, Jaffray E, Song J, Zheng J, Rodriguez MS, Hay RT, Chen Y. Role of an N-terminal site of Ubc9 in SUMO-1, -2, and -3 binding and conjugation. Biochemistry. 2003;42:9959–69. doi: 10.1021/bi0345283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.VanDemark AP, Hofmann RM, Tsui C, Pickart CM, Wolberger C. Molecular insights into polyubiquitin chain assembly: crystal structure of the Mms2/Ubc13 heterodimer. Cell. 2001;105:711–20. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00387-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang DT, Paydar A, Zhuang M, Waddell MB, Holton JM, Schulman BA. Structural basis for recruitment of Ubc12 by an E2 binding domain in NEDD8’s E1. Mol Cell. 2005;17:341–50. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang DT, Hunt HW, Zhuang M, Ohi MD, Holton JM, Schulman BA. Basis for a ubiquitin-like protein thioester switch toggling E1–E2 affinity. Nature. 2007;445:394–8. doi: 10.1038/nature05490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods in Enzymology. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jones TA, Zou JY, Cowan SW, Kjeldgaard M. Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr A. 1991;47:110–118. doi: 10.1107/s0108767390010224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Laskowski R, MacArthur M, Hutchinson E, Thorton J. PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J Appl Cryst. 1993;26:283–291. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Delano WL. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. DeLano Scientific LLC; San Carlos, CA, USA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yunus A, Lima CD. Purification and activity assays for Ubc9, the ubiquitin conjugating enzyme for the small ubiquitin-like modifier SUMO. Methods in Enzymology. 2005;398:74–87. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)98008-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.