Abstract

Serious defects in the epidermal keratinocyte lipid transporter ABCA12 are known to result in a deficient skin lipid barrier, leading to harlequin ichthyosis (HI). HI is the most severe inherited keratinizing disorder and is frequently fatal in the perinatal period. To clarify the role of ABCA12, ABCA12 expression was studied in developing human skin and HI lesions artificially reconstituted in immunodeficient mice. By immunofluorescent study, ABCA12 was expressed in the periderm of the early stage two-layered human fetal epidermis. After formation of a three-layered epidermis, ABCA12 staining was seen throughout the entire epidermis. ABCA12 mRNA expression significantly increased during human skin development and reached 62% of the expression in normal adult skin, whereas the expression rate of transglutaminase 1, loricrin, and kallikrein 7 remained low. We transplanted keratinocytes from patients with HI and succeeded in reconstituting HI skin lesions in immunodeficient mice. The reconstituted lesions showed similar changes to those of patients with HI. Our findings demonstrate that ABCA12 is highly expressed in fetal skin and suggest that ABCA12 may play an essential role under both the wet and dry conditions, including the dramatic turning point from a wet environment of the amniotic fluid to a dry environment after birth.

One important event during terminal differentiation of stratified squamous epithelia such as the epidermis is the formation of intercellular lipid layers in the stratum corneum. Intercellular lipid layers in the stratum corneum are essential for epidermal barrier function. The lipid layers are formed from the extruded lipid contents secreted from lamellar granules within granular layer keratinocytes.

The ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter superfamily is one of the largest gene families, encoding a highly conserved group of proteins involved in energy-dependent (active) transport of a variety of substrates across biological membranes, including ions, amino acids, peptides, carbohydrates, and lipids.1,2,3 ABC transporters have nucleotide binding folds located in the cytoplasm and use energy from ATP to transport substrates across the cell membrane.4 ABC genes are widely dispersed throughout the eukaryotic genome and are highly conserved between species.5,6 The ABCA subfamily comprises 12 full transporter proteins and one pseudogene (ABCA11). The ABCA subclass has received considerable attention, because mutations in these genes have been implicated in several human genetic diseases.7,8,9,10,11 Recent studies have clarified that many members of the ABCA subclass play an important role in endogenous lipid transport.12,13,14,15,16,17

In 2005, ABCA12, a member of the ABCA subfamily, was reported to underlie harlequin ichthyosis (HI), one of the most devastating genodermatoses.18,19 HI was known to show several morphological abnormalities reflecting defective lipid content: absent or abnormal lamellar granules in the granular keratinocytes, lipid droplets in the stratum corneum, and a lack of extracellular lipid lamellae.20,21,22,23,24,25,26 We demonstrated that ABCA12 works as an epidermal keratinocyte lipid transporter and that defective ABCA12 results in a loss of the skin lipid barrier, leading to HI.18

In HI skin, epidermal morphogenesis already shows significant alterations in utero.20,27,28,29,30,31 Affected neonates usually show the most severe, life-threatening symptoms such as large, thick, platelike scales over the whole body, ectropion, eclabium, and flattened ears from birth.32 Patients with HI usually die during the first few weeks of life from secondary infection, severe anemia, dehydration, circulatory disturbance, or renal failure. However, once patients with HI have survived beyond the perinatal period, their skin symptoms tend to be less severe, and some long-term survivors even show clinical features of the milder nonbullous congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma.33,34 Some survivors can even stop taking oral retinoids. From these clinical findings, we hypothesized that ABCA12 deficiency is the most critical at around the time of birth and that the negative effects of ABCA12 deficiency might be reduced or compensated for after the baby grows beyond the perinatal period.

In the present study, to clarify further the pathomechanisms of severe HI manifestations from birth and the critical role of ABCA12 in the neonatal period, ABCA12 expression was studied in detail in developing human skin and artificially reconstituted HI lesions grown on immunodeficient mice. This is the first report describing ABCA12 expression during embryonic and fetal skin ontogeny, and it demonstrates that ABCA12 is highly expressed in the upper epidermis from the second trimester. Furthermore, we succeeded in establishing a model system for regenerated HI lesions harboring ABCA12 mutations in adult skin with reduced ABCA12 expression in the reconstituted HI skin lesions. The skin lesions reconstituted in the dry environment were similar to the original lesions seen at birth. The present results suggest that ABCA12 may play an essential role both in the wet conditions during fetal development and in the dry conditions including the dramatic turning point from wet condition in the amniotic fluid to dry environment around the birth.

Materials and Methods

Human Fetal Skin Specimens

Normal human fetal tissue was acquired (after informed consent was obtained) from Sapporo Maternity-Women’s Hospital (Sapporo, Japan). Human embryonic and fetal skin specimens were obtained from abortuses of 7 to 22 weeks estimated gestational age (EGA). An HI fetal skin sample was obtained from an abortus at 21 weeks EGA that had been diagnosed with HI by prenatal skin biopsy.30 Skin specimens were taken from the trunk, scalp, and fingers and processed for the present study. EGA was determined from maternal history, fetal measurements (crown, rump, and foot length), and comparative histological appearance of the epidermis.

Antibodies

Immunofluorescence labeling was performed as described below. We used anti-ABCA12 antisera18 as a primary antibody. For control immunostaining, we also used mouse monoclonal anti-transglutaminase 1 (TGase1) antibody BT-621 (Biomedical Technologies, Inc., Stoughton, MA), because TGase1 is a major keratinization marker that is known to cross-link several precursor proteins in the formation of the cornified cell envelope during keratinocyte differentiation. Rabbit anti-human glucosylceramide antibody (Glycobiotech, Kükels, Germany) was used to clarify the expression sites of the lipid in the epidermis during development. Immunolabeling for keratin 10, a keratinization marker, and cathepsin D, a component of lamellar granules, was performed using mouse anti-human keratin 10 antibody (DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) and rabbit anti-human cathepsin D antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA) in normal and HI fetal skin. Rat anti-human HLA class I antibody (Serotec Ltd., Oxford, UK) was also used to differentiate human keratinocyte-derived epidermis from host murine epidermis.

Immunofluorescent Labeling

Immunofluorescent labeling was performed as previously described.35 In brief, 6-μm-thick sections of fresh skin samples cut using a cryostat were prepared for immunolabeling. Sections were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes at 4°C for labeling with anti-human HLA class I antibody or in acetone for 10 minutes at room temperature for labeling with other antibodies (ABCA12, TGase1, keratin 10, and cathepsin D) except for anti-human glucosylceramide antibody. We performed glucosylceramide labeling without any fixation. The sections were incubated in primary antibody solution for 2 hours at room temperature. Primary antibodies and dilutions were as follows: rabbit polyclonal anti-human ABCA12 antibody,18 1:800; mouse monoclonal anti-TGase1 antibody, BT-621, 1:100; rabbit polyclonal anti-human glucosylceramide antibody, 1:10; mouse polyclonal anti-human keratin 10 antibody, 1:100; rabbit polyclonal anti-human cathepsin D antibody, 1:10; and rat anti-human HLA class I antibody, 1:100. The sections were then incubated in each secondary antibody: fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin, anti-rabbit immunoglobulin, anti-rat immunoglobulin, or tetramethylrhodamine-5-(and -6)-isothiocyanate-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit immunoglobulin (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, PA) diluted 1:100 for 2 hours at room temperature, followed by 10 μg/ml TO-PRO-3 iodide (Molecular Probes, San Diego, CA) or propidium iodide (Dojindo Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan) to counterstain nuclei for 10 minutes at 37°C. Sections were observed under an Olympus FluoView confocal laser scanning microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction Analysis

To quantify the ABCA12 mRNA expression levels together with TGase1, loricrin, and kallikrein 7 (KLK7) in fetal skin, total RNA was extracted from fresh skin samples. Commercial epidermal mRNA obtained from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA) was used only for the specimen at 18 and 20 weeks EGA. In addition, total RNA was extracted from fresh skin samples obtained from a human adult (a generally healthy Japanese male without any skin disease) at a surgical operation of a benign subcutaneous tumor, and the RNA sample was used for the real-time polymerase chain reaction analysis. RNA samples were analyzed by the ABI prism 7000 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Primers and probes specific for ABCA12, TGase1, loricrin, and KLK7 were obtained from the TaqMan gene expression assay (Applied Biosystems: Hs00292421_m1, Hs00165929_m1, Hs01894962_s1 and Hs00192503_m1).

Differences between the mean CT values of ABCA12, TGase1, loricrin, and KLK7 and those of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), β-actin, or large ribosomal protein (Applied Biosystems) were calculated as ΔCTsample = CTABCA12 (or other keratinization markers) − CTGAPDH (or other housekeeping genes) and those of ΔCT for the normal adult skin as ΔCTcalibrator = CTABCA12 (or other keratinization markers) − CTGAPDH (or other housekeeping genes). Final results for fetal skin sample/adult skin (%) were determined by 2−(ΔCtsample − ΔCTcalibrator).

Skin Reconstruction from Normal Human Keratinocytes and HI Patients’ Keratinocytes with Normal Fibroblasts

Normal human fibroblasts and keratinocytes were purchased from Kurabo (Osaka, Japan). We established primary cultures of skin cells from two patients with HI. One patient harbored a homozygous splice site mutation c.3295-2A>G and the other harbored heterozygous mutations: p.Ser387Asn and c.4158_4160del (p.Thr1387del) as previously reported.36 In detail, patients’ keratinocytes were isolated from lesional epidermis after separation from the dermis by overnight treatment of dispase I (Godoshusei, Chiba, Japan). After 0.25% trypsin digestion for 5 minutes, epidermal cells were collected and cultured in defined keratinocyte serum-free medium (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA). Normal human keratinocytes were grown in the same culture medium. Normal human fibroblasts were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen) and antibiotics. All of the cells were maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Engraftment was performed as previously described.37 Equal numbers of keratinocytes (normal human keratinocytes or keratinocytes from patients with HI) and normal human fibroblasts were combined at a final density of 6 to 8 × 106 cells, and the cells were thoroughly mixed. This cell slurry was engrafted into a silicon chamber attached to the back of an anesthetized severe combined immunodeficient mouse (Clea, Tokyo, Japan). After 1 week, the wounds had healed, and the chamber tops were removed. The skin reconstitution was completed 2 to 3 weeks thereafter.

We succeeded in reconstituting HI skin using keratinocytes from a patient with HI who had a homozygous mutation, c.3295-2A>G,18 using the methods described above. Thus, with the same methods, we reconstituted HI lesions using keratinocytes from another patient with HI who had heterozygous mutations affecting both ABCA12 alleles, p.Ser387Asn and c.4158_4160del (p.Thr1387del) (see Ref. 37 for further detailed analysis of the reconstituted lesions).

Transmission Electron Microscopy

For transmission EM, fresh biopsies of fetal skin and reconstituted skin were fixed in 5% glutaraldehyde solution, postfixed in 1% OsO4, dehydrated, and embedded in Epon 812. All of the samples were ultrathin-sectioned at a thickness of 70 nm and stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Photographs were taken using a Hitachi H-7100 transmission electron microscope.

This study was approved by the medical ethical committees of Hokkaido University Graduate School of Medicine, Sapporo, Japan. The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki Principles.

Results

ABCA12 Expressed in the Periderm of Early Developing Epidermis and in the Upper Epidermis at the Later Stages

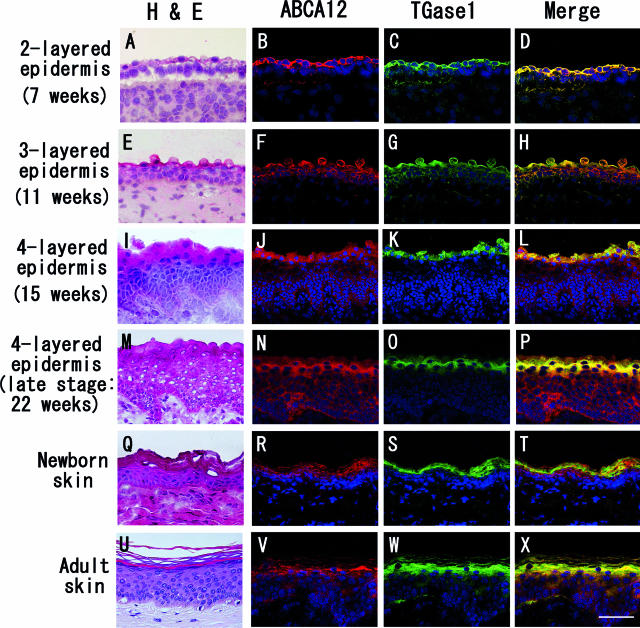

ABCA12 expression was seen in the periderm during the early period when the two-layered epidermis forms, about 6 to 9 weeks EGA (Figure 1B). In the two-layered epidermis, both ABCA12 and TGase1 were expressed only in periderm cells (Figure 1, A–D). In the three-layered epidermis (10 to 13 weeks EGA), ABCA12 staining was seen in the entire epidermis, including intense periderm staining, whereas TGase1 staining was restricted to the periderm (Figure 1, E–H). A similar pattern was observed in the period of four or more layered epidermis before keratinization (14 to 22 weeks EGA) (Figure 1, I–P). In the newborn skin, ABCA12 and TGase1 staining were restricted to upper layers of epidermis, mainly granular layers (Figure 1, Q–T). These staining patterns are similar to those in normal adult skin (Figure 1, U–X) as previously reported.18

Figure 1.

Expression of ABCA12 and TGase1 in developing skin. Fetal skin samples of 49 to 154 days EGA and newborn skin were double-stained for ABCA12 (red) and TGase1 (green). To show the anatomy of the sections clearly, photos of H&E-stained sections were included (A, E, I, M, Q, and U). A–D: In the two-layered epidermis (7 weeks EGA), both ABCA12 and TGase1 are expressed only in periderm cells. In the three-layered epidermis (11 weeks EGA; E–H), ABCA12 staining is seen in the entire epidermis, especially intensely within the periderm layer, whereas TGase1 staining remains only in the periderm. A similar pattern is observed in the four or more layered epidermis period (15 and 22 weeks EGA; I–P). Q–T: In the newborn skin, ABCA12 and TGase1 are seen only in the upper layer of the epidermis, mainly in the granular layers. These staining patterns are similar to those in normal adult skin (U–X). ABCA12, red (tetramethylrhodamine-5-(and -6)-isothiocyanate); TGase1, green (FITC); nuclear stain, blue (TO-PRO-3 iodide). Scale bar = 50 μm.

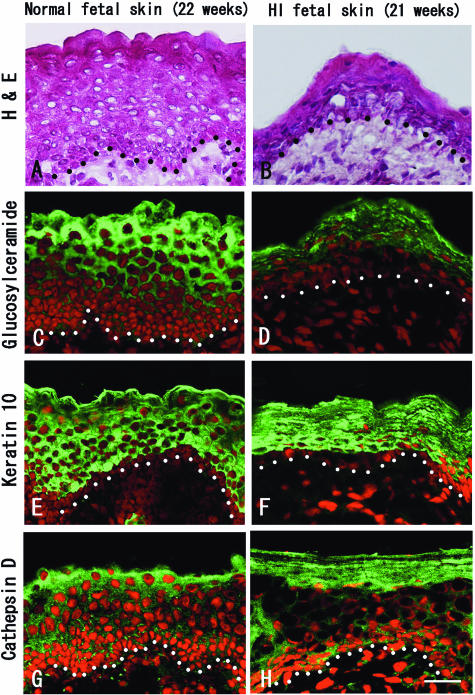

Glucosylceramide Expression in Normal Fetal Skin and Its Reduction in HI Fetal Skin

We performed immunofluorescent staining of glucosylceramide, one of the most important precursors of ceramide, in normal and HI fetal skin. In normal fetal skin at 22 weeks EGA, the expression of glucosylceramide was observed in the upper epidermis, including periderm (Figure 2C). HI fetal skin at 21 weeks EGA shows marked hyperkeratosis by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining (Figure 2B). In HI fetal skin, the expression of glucosylceramide was obviously reduced, and only weak expression was seen in the upper epidermis (Figure 2D), although the expression of keratin 10, a keratinization marker, and cathepsin D, a component of lamellar granules, in HI fetal skin (Figure 2, F and H) were similar to those in normal fetal skin (Figure 2, E and G). Thus, the reduced glucosylceramide expression was thought to be a specific change resulting from an abnormality in HI epidermis and was specifically caused by an ABCA12 deficiency in HI fetal skin.

Figure 2.

Glucosylceramide expression was confirmed in normal fetal epidermis at 22 weeks EGA, although the expression was remarkably weak in HI fetal epidermis. H&E staining (A and B) and immunofluorescent staining (C–H) in normal and HI fetal skin. In normal fetal skin at 22 weeks EGA, glucosylceramide was seen in the upper epidermis, including periderm (C). In contrast, the expression of glucosylceramide was significantly reduced in the upper epidermis of HI fetal skin at 21 weeks EGA (D). The expression of keratin 10 (E and F) and cathepsin D (G and H) showed no apparent difference in normal and HI fetal skin. Black and white dots indicate basement membrane. Glucosylceramide, keratin 10, and cathepsin D, green (FITC); nuclear stain, red (propidium iodide). Scale bar = 30 μm.

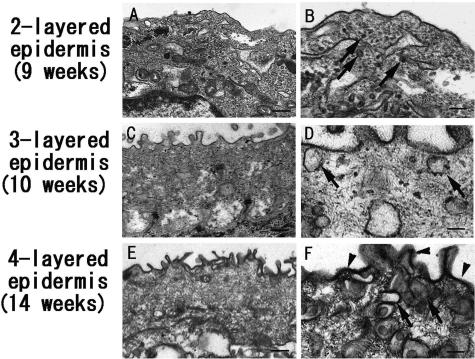

Many Vesicles Seen in the Periderm

In two-layered epidermis (6 to 9 weeks EGA) (Figure 3, A and B), the periderm contained many vesicles (arrows). In the three-layered epidermal stage (10 to 13 weeks EGA) (Figure 3, C and D), vesicles were observed at the cell periphery of periderm cells. In four or more layered epidermis before keratinization (14 to 22 weeks EGA) (Figure 3, E and F), the number of vesicles close to the cell membrane significantly increased. Due to the intense ABCA12 staining in the cytoplasm of periderm cells, some of the vesicles were thought to be associated with ABCA12 staining seen in this period, although a large number of these vesicles are thought to be pinocytic vesicles. The thickening of the periderm cell membrane was markedly observed in the four-layered epidermis (Figure 3F).

Figure 3.

Electron microscopic findings of human developing epidermis. A and B: In the two-layered epidermis (9 weeks EGA), the periderm contains many vesicles (arrows). C and D: In the three-layered epidermis (10 weeks EGA), vesicles (arrows) are observed at the periderm cell periphery. E and F: In the four-layered epidermis (14 weeks EGA), the number of vesicles (arrows) close to the cell membrane significantly increased. The thickening of the periderm cell membrane (arrowheads) was seen in the four-layered epidermis (F). Scale bars: 400 nm (A, C, and E) and 200 nm (B, D, and F).

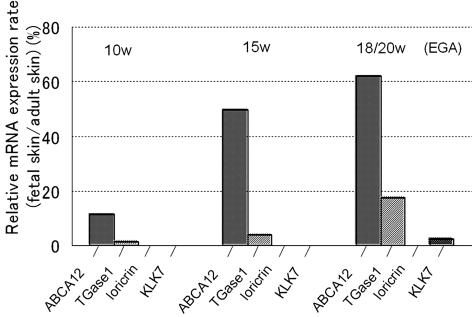

Increased ABA12 mRNA Expression in Fetal Skin at 15 Weeks EGA

We examined the expression of ABCA12, TGase1, loricrin, and KLK7 mRNA by real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction. The results were normalized by expression of three housekeeping genes, GAPDH, β-actin, and large ribosomal protein, and the expression level of each mRNA was converted to a percentage rate compared with that of the normal adult skin. The expression level of ABCA12 mRNA normalized to GAPDH remarkably increased after 15 weeks EGA when compared with an earlier developmental stage (10 weeks EGA) (Figure 4). Expression rates of other keratinization-related molecules studied for controls, TGase1, loricrin, and KLK7, remained very low, whereas the expression rate of ABCA12 increased by up to 62% (at 18 and 20 weeks EGA) during development. The expression level of loricrin was very low (expression level at 18 and 20 weeks EGA/expression level in adult = 0.019%), probably due to the extremely high expression level of loricrin in adult samples. The results normalized to other housekeeping genes, β-actin, or large ribosomal protein, showed a similar pattern. ABCA12 mRNA expression during development became up-regulated to 86% (normalized to β-actin) or 62% (normalized to large ribosomal protein), whereas TGase1, loricrin, and KLK7 remained very low (data not shown). This increase in ABCA12 mRNA expression is consistent with ABCA12 immunofluorescence findings during human epidermal development.

Figure 4.

Expression of ABCA12 was higher in fetal skin compared with those of other keratinization markers. The mRNA expression of ABCA12, TGase1, loricrin, and KLK7 in fetal skin was studied by real-time polymerase chain reaction analysis, normalized by GAPDH. mRNA expression rates in fetal skin compared with adult skin expression level (fetal skin/adult skin) were summarized in the graph. At 15 weeks EGA, the rate of ABCA12 mRNA expression was significantly increased compared with that at 10 weeks EGA, which reached to almost 62% at 18 and 20 weeks EGA. On the other hand, mRNA expression rates of TGase1, loricrin, and KLK7 remained low during fetal skin development. Each expression rate at 18 and 20 weeks EGA was as follows: TGase1, 17%; loricrin, 0.019%; KLK7, 2.4%. This result was consistent with that using two other housekeeping genes, β-actin, and large ribosomal protein.

Remarkable Hyperkeratosis in Reconstituted HI Lesions

We regenerated normal human skin using cultured normal human keratinocytes and fibroblasts. Four weeks after transplantation, the grafts exhibited an ordinary skin appearance (Figure 5B). Immunohistochemical staining for anti-human HLA class I showed that the reconstituted epidermis and dermis had been organized by surviving human cells (data not shown). An epidermis with a morphology resembling that of normal epidermis was observed in reconstituted skin using normal control keratinocytes and normal human fibroblasts (Figure 5, E and F). Frozen sections stained with H&E showed that the reconstituted epidermis composed of keratinocytes with normal morphology was of a normal thickness (Figure 5F), although the dermal band of regenerated human cells was thin.

Figure 5.

Establishment of a reconstituted skin model for HI. A–D: Macroscopic features of human skin and regenerated skin. We regenerated human skin using cultured normal human keratinocytes (B) and cells from a patient with HI (D) on the back of severe combined immunodeficient mice. E–H: H&E staining of human skin and regenerated skin. Similar morphological features could be seen in the normal human skin (E) and reconstituted normal skin (F). The reconstituted HI skin grown from back lesions showed thick scales (D), although the hyperkeratosis was milder in the reconstituted HI grafted area (H) than the original HI patient skin (G). I–L: ABCA12 immunostaining. Strong ABCA12 expression (green) was observed in the granular layers in normal human skin (I) and reconstituted normal human skin (J). Significantly reduced ABCA12 expression was observed in the granular layers of the HI patient skin (K) and in the reconstituted HI lesion (L). Very weak ABCA12 immunostaining was seen in the cytoplasm of spinous layer cells in each section (I–L). ABCA12, green (FITC); nuclear stain, red (propidium iodide). M–P: Glucosylceramide immunostaining. Cytoplasmic staining for glucosylceramide (green) was seen in the upper epidermis of normal human skin (M) and of reconstituted normal skin (N). Only weak cytoplasmic staining for glucosylceramide was observed in the upper epidermis of HI patient’s skin (O) and in the reconstituted HI lesion (P). Glucosylceramide, green (FITC); nuclear stain, red (propidium iodide). Q–X: Electron microscopic features of the cornified layers of the skin. Q–T: Ultrastructure of cornified cell layers. Accumulation of lipid vacuoles (asterisks) was observed in the cornified layer cells in the patient skin (S) and in the reconstituted HI lesion (T). Those vacuoles were not seen in normal skin (Q) or reconstituted normal skin (R). U–X: Ultrastructure of lamellar granules at the boundary between granular and cornified cell layers. Normal lamellar granules secreting their content to the extracellular space (arrows) were observed in the normal human skin (U) and the reconstituted normal skin (V). Abnormal lamellar granules (arrowheads) were seen in the granular layer cells both in the patient’s skin (W) and in the reconstituted HI lesion (X). A, E, I, M, Q, and U: Normal human skin. B, F, J, N, R, and V: Skin regenerated by normal keratinocytes at 4 weeks after transplantation. C, G, K, O, S, and W: Original skin lesion from the HI patient whose keratinocytes were used for the reconstitution. D, H, L, P, T, and X: Skin regenerated from HI patient keratinocytes at 4 weeks after transplantation. Scale bars: 30 μm (E, F, H, and P), 100 μm (G), 500 nm (T), and 250 nm (X).

We regenerated HI skin lesions using cultured keratinocytes harboring ABCA12 mutations p.Ser387Asn and c.4158_4160del (p.Thr1387del) and normal human fibroblasts. Four weeks after transplantation, the grafts exhibited a rugged external epidermal surface and marked hyperkeratosis (Figure 5D). Immunohistochemical staining for anti-human HLA class I showed that the reconstituted epidermis and dermis were organized by human cells (data not shown). Frozen sections with H&E staining showed that the morphology of the reconstituted skin composed of cells from a patient with HI revealed a thickened stratum corneum (Figure 5H), similar to that in the original HI patient lesions (Figure 5G). From the basal layers to the granular layers, there were no differences between reconstituted skin from HI patient keratinocytes and normal human keratinocytes.

Reduced ABCA12 Expression in Reconstituted HI Skin

Strong ABCA12 expression was observed in the granular layers of the normal human skin (Figure 5I), and a similar pattern was seen in reconstituted normal human skin (Figure 5J). Significantly reduced ABCA12 expression was observed in the granular layers of the skin of the patient with HI (Figure 5K). In the reconstituted HI lesional epidermis, only weak ABCA12 expression (Figure 5L) was seen, similar to that in the skin of the patient with HI. Very weak ABCA12 immunostaining was seen in the spinous layers in all samples (Figure 5, I–L). Spinous layer ABCA12 staining intensity showed no differences between control or the HI samples.

Weak Glucosylceramide Expression in HI Patien’s Skin and in Reconstituted HI Skin

In normal human skin, strong glucosylceramide expression was seen in the upper epidermis, mainly in the granular layer (Figure 5M). Glucosylceramide was distributed broadly within the entire cytoplasm of the upper epidermal cells. A similar pattern was seen in the normal keratinocyte-reconstituted skin (Figure 5N).

In the skin of the patient with HI, only weak glucosylceramide expression was observed around nuclei in the upper epidermal cells (Figure 5O). A similar pattern of glucosylceramide expression was seen in the reconstituted HI skin lesion (Figure 5P).

Abnormal Lamellar Granules and Lipid Accumulation within the Resonstituted HI Epidermis

Ultrastructurally, in the normal reconstituted epidermis, keratin-filaggrin material occupied the cytoplasm of cornified cells, and no lipid vacuoles were seen in the cornified cell layers (Figure 5R). At the boundary between the granular and cornified cell layers, uniformly small lamellar granules containing lamellar structures were observed, and lamellar granule contents were secreted into the extracellular space (Figure 5V, arrows). In the cytoplasm of the granular layer cells, normal lamellar granules were seen (data not shown). All of these features were seen in the normal human epidermis in vivo (Figure 5, Q and U).

Similar to the skin of the patient with HI (Figure 5, S and W), the reconstituted epidermis using keratinocytes from the patient with HI always demonstrated multiple, typical features of HI skin, including abnormal lipid inclusions that were frequently observed in the cornified layer cells (Figure 5T, asterisks) and abnormal lamellar granules characteristic of HI that were also localized close to the extracellular space (Figure 5X, arrowheads). Some lipid inclusions in the cornified layer cells were apparently empty, although others contained electron-dense vesicular or granular material (Figure 5, S and T). In the upper spinous and granular layers, abnormal lamellar granules in the skin of patient with HI and reconstituted HI skin lacked the normal lamellar structure but contained electron-dense vesicular, granular, or irregularly shaped material (Figure 5, W and X). In normal human skin and normal reconstituted skin, intact lamellar granules with lamellar structures were observed fused with the cell membrane, and the contents of the lamellar granules were secreted into the intercellular space (Figure 5, U and V). Conversely, some abnormal lamellar granules in the skin of the patient with HI and reconstituted skin were observed as empty. In addition, HI keratinocytes and derived tissue showed abnormal vesicular lamellar granules that had become congested in the cytoplasm of granular layer cells (Figure 5, W and X).

Discussion

From the present results, we have demonstrated that ABCA12 is already expressed from the early stages of fetal epidermal development. We also found that ABCA12 staining showed an extended distribution covering the entire epidermis from the three-layered epidermal stage. The results were consistent with a previous report of another lamellar granule-associated protein, the antigen recognized by the AE17 antibody, which was also detected from the two-layered epidermal stage in the periderm35 and in the underlying intermediate cell layers of the epidermis from the stage of three-layered epidermis. The sequential expression patterns of keratinization-related molecules in the periderm were associated with vesicles and the thickening of the cell membrane of periderm cells revealed by electron microscopy.35 Moreover, the increased level of ABCA12 mRNA expression at 15 weeks EGA also reflected the ABCA12 immunofluorescent staining throughout the entire epidermis during human epidermal development. This increasing level and extended distribution of ABCA12 expression is unique compared with the expression of other keratinization-related proteins, such as TGase1, loricrin, and KLK7, which were not up-regulated during fetal skin development. In addition, post-110-day fetal epidermis was reported to be rich in ceramides, glycosphingolipids, triglycerides, and sterol esters.38 By immunofluorescence study, glucosylceramide was expressed in the upper epidermis of the normal fetal skin, although the HI fetal skin at 21 weeks EGA showed marked reduction of glucosylceramide expression.

From these findings, we hypothesized that the periderm cells secrete lipid during their regression, similar to the granular layer cells of the adult epidermis. This putative role of the periderm is closely associated with an increase of ABCA12 expression before keratinization during human fetal skin development. We thought that ABCA12 and the related lipid transport system might play an important role under hydrated conditions in the amniotic fluid during development. However, we do not have enough data to support this hypothesis and, in previous reports, there was no apparent morphology abnormality in the periderm of HI fetuses.20,26

Furthermore, to confirm a role of ABCA12 in dry conditions after delivery, we reconstituted HI lesional skin from cultured patient keratinocytes harboring mutations in ABCA12 under dry conditions, ie, on the back of immunodeficient mice using a silicone chamber. The reconstituted skin showed similar morphological features to HI patient skin lesions even in dry conditions. These grafts exhibited abnormal surface features, ie, rugged surface and marked hyperkeratosis typically sharing many features seen in the surface of HI patient skin. Histological analysis showed that the reconstituted skin composed of patient keratinocytes revealed an extraordinarily thick stratum corneum. Immunofluorescence studies of ABCA12 and glucosylceramide expression in reconstituted skin showed similar staining patterns to those of the original normal skin or HI patient skin. The abnormal distribution of glucosylceramide in reconstituted HI skin suggests that dysfunction of ABCA12 affects glucosylceramide transport, even in the reconstituted HI skin. Ultrastructurally, the reconstituted epidermis from the HI patient’s cells showed abnormal granular layer lamellar granules and lipid droplets in the cornified layer cells. ABCA12 expression was remarkably reduced in the reconstituted skin similar to that seen in the HI patient skin lesion. Thus, we have generated and characterized a model system for HI skin lesions in vivo by regeneration of HI lesions using primary cultured patient keratinocytes.

From these findings, we have demonstrated that defective ABCA12 causes HI lesions even in dry conditions. Moreover, this system provides a powerful tool to analyze ABCA12 gene function and to evaluate various treatments for HI. This will also prove useful to develop more effective gene therapy approaches for HI.

Long-term survivors of HI usually show lamellar ichthyosis or an nonbullous congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma phenotype, which is milder than the typical HI phenotype, as patients become older. The precise mechanisms for this improvement are not well understood. However, we might expect a compensatory mechanism for ABCA12 deficiency, which might work in a dry environment after delivery but not under wet conditions, for example during fetal development. We expected that ABCA12 gene expression would be up-regulated in the dry environment and that residual activities of ABCA12 peptides from the mutant allele contribute to the improvement of the clinical features. However, in our present study, we failed to observe any apparent up-regulation of ABCA12 expression in the reconstituted HI skin model by immunofluorescent staining, compared with the original patient skin lesion. In this context, we predict that specific mechanisms other than a direct up-regulation of ABCA12 expression may compensate in the reconstituted skin in the dry environment.

In a separate disease entity, the self-healing collodion baby with tranglutaminase1 mutations, after birth, water molecules are naturally lost from the skin and the mutated TGase1 enzyme is predicted to isomerize back to a partially active cis form, resulting in recovery of the phenotype as a patient becomes older.39 Of course, the compensatory mechanism for ABCA12 defects is likely to be different from TGase1 compensation in self-healing lamellar ichthyosis. As yet unknown lipid transporters and transport mechanisms other than ABCA12 may be involved in lipid transport, accumulation, and secretion in human keratinocytes. Further comprehensive studies are needed to clarify the alternative lipid transport mechanisms involved in the keratinization processes and to elucidate the compensatory mechanisms for ABCA12 deficiency in patients with HI.

Acknowledgments

We thank Megumi Sato and Akari Nagasaki for help on this project and Sapporo Maternity-Womens’ Hospital (Sapporo, Japan) for providing fetal skin samples.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Masashi Akiyama, M.D., Ph.D, or Hiroshi Shimizu, M.D., Ph.D., Department of Dermatology, Hokkaido University Graduate School of Medicine, N15 W 7, Sapporo 060-8638, Japan. E-mail: akiyama@med.hokudai.ac.jp.

Supported in part by grants-in-aid Kiban B 18390310 (to M.A.) and Kiban A 17209038 (to H.S.) from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture of Japan.

References

- Allikmets R, Gerrard B, Hutchinson A, Dean M. Characterization of the human ABC superfamily: isolation and mapping of 21 new genes using the expressed sequence tags database. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5:1649–1655. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.10.1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borst P, Elferink RO. Mammalian ABC transporters in health and disease. Annu Rev Biochem. 2002;71:537–592. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.102301.093055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean M, Rzhetsky A, Allikmets R. The human ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter superfamily. Genome Res. 2001;11:1156–1166. doi: 10.1101/gr.184901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein I, Sarkadi B, Varadi A. An inventory of the human ABC proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1461:237–262. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(99)00161-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins CF. ABC transporters: from microorganisms to man. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1992;8:67–113. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.08.110192.000435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peelman F, Labeur C, Vanloo B, Roosbeek S, Devaud C, Duverger N, Denefle P, Rosir M, Van dekerckhove J, Rosseneu M. Characterization of the ABCA transporter subfamily: identification of prokaryotic and eukaryotic members, phylogeny and topology. J Mol Biol. 2003;325:259–274. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01105-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allikmets R, Singh N, Sun H, Shroyer NF, Hutchinson A, Chidambaram A, Gerrard B, Baird L, Stauffer D, Peiffer A, Rattner A, Smallwood P, Li Y, Anderson KL, Lewis RA, Nathans J, Leppert M, Dean M, Lupski JR. A photoreceptor cell-specific ATP-binding transporter gene (ABCR) is mutated in recessive Stargardt macular dystrophy. Nat Genet. 1997;15:236–246. doi: 10.1038/ng0397-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allikmets R, Shroyer NF, Singh N, Seddon JM, Lewis RA, Bernstein PS, Peiffer A, Zabriskie NA, Li Y, Hutchinson A, Dean M, Lupski JR, Leppert M. Mutation of the Stargardt disease gene (ABCR) in age-related macular degeneration. Science. 1997;277:1805–1807. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5333.1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Wilson A, Marcil M, Clee SM, Zhang LH, Roomp K, van Dam M, Yu L, Brewer C, Collins JA, Molhuizen HO, Loubser O, Ouelette BF, Fichter K, Ashbourne-Excoffon KJ, Sensen CW, Scherer S, Mott S, Denis M, Martindale D, Frohlich J, Morgan K, Koop B, Pimstone S, Kastelein JJ, Genest J, Jr, Hayden MR. Mutations in ABC1 in Tangier disease and familial high-density lipoprotein deficiency. Nat Genet. 1999;22:336–345. doi: 10.1038/11905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rust S, Rosier M, Funke H, Real J, Amoura Z, Piette JC, Deleuze JF, Brewer HB, Duverger N, Denefle P, Assmann G. Tangier disease is caused by mutations in the gene encoding ATP-binding cassette transporter 1. Nat Genet. 1999;22:352–355. doi: 10.1038/11921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulenin S, Nogee LM, Annilo T, Wert SE, Whitsett JA, Dean M. ABCA3 gene mutations in newborns with fatal surfactant deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1296–1303. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orsó E, Broccardo C, Kaminski WE, Bottcher A, Liebisch G, Drobnik W, Gotz A, Chambenoit O, Diederich W, Langmann T, Spruss T, Luciani MF, Rothe G, Lackner KJ, Chimini G, Schmitz G. Transport of lipids from Golgi to plasma membrane is defective in tangier disease patients and Abc1-deficient mice. Nat Genet. 2000;24:192–196. doi: 10.1038/72869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz G, Langmann T. Structure, function and regulation of the ABC1 gene product. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2001;12:129–140. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200104000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski WE, Piehler A, Pullmann K, Porsch-Ozcurumez M, Duong C, Bared GM, Buchler C, Schmitz G. Complete coding sequence, promoter region, and genomic structure of the human ABCA2 gene and evidence for sterol-dependent regulation in macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;281:249–258. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamano G, Funahashi H, Kawanami O, Zhao LX, Ban N, Uchida Y, Morohoshi T, Ogawa J, Shioda S, Inagaki ABCA3 is a lamellar body membrane protein in human lung alveolar type II cells. FEBS Lett. 2001;508:221–225. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03056-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata K, Yamamoto A, Ban N, Tanaka AR, Matsuo M, Kioka N, Inagaki N, Ueda K. Human ABCA3, a product of a responsible gene for abca3 for fetal surfactant deficiency in new borns, exhibits unique ATP hydrolysis activity and generates intracellular multilamellar vesicles. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;324:262–268. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allikmets R. Simple and complex ABCR: genetic predisposition to retinal disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;67:793–799. doi: 10.1086/303100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama M, Sugiyama-Nakagiri Y, Sakai K, MacMillan JR, Goto M, Arita K, Tsuji-Abe Y, Tabata N, Matsuoka K, Sasaki R, Sawamura D, Shimizu H. Mutations in lipid transporter ABCA12 in harlequin ichthyosis and functional recovery by corrective gene transfer. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1777–1784. doi: 10.1172/JCI24834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelsell DP, Norgett EE, Unsworth H, Teh MT, Cullup T, Mein CA, Dopping-Hepenstal PJ, Dale BA, Tadini G, Fleckman P, Stephens KG, Sybert VP, Mallory SB, North BV, Witt DR, Sprecher E, Taylor AE, Ilchyshyn A, Kennedy CT, Goodyear H, Moss C, Paige D, Harper JI, Young BD, Leigh IM, Eady RA, O’Toole EA. Mutations in ABCA12 underlie the severe congenital skin disease harlequin ichthyosis. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:794–803. doi: 10.1086/429844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama M, Kim D-K, Main DM, Otto CE, Holbrook KA. Characteristic morphologic abnormality of harlequin ichthyosis detected in amniotic fluid cells. J Invest Dermatol. 1994;102:210–213. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12371764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale BA, Holbrook KA, Fleckman P, Kimball JR, Brumbaugh S, Sybert VP. Heterogeneity in harlequin ichthyosis, an inborn error of epidermal keratinization: variable morphology and structural protein expression and a defect in lamellar granules. J Invest Dermatol. 1990;94:6–18. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12873301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner ME, O’Guin WM, Holbrook KA, Dale BA. Abnormal lamellar granules in harlequin ichthyosis. J Invest Dermatol. 1992;99:824–829. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12614791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto K, Khan S. Harlequin fetus with abnormal lamellar granules and giant mitochondria. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19:247–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1992.tb01666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto K, De Dobbeleer G, Kanzaki T. Electron microscopic studies of harlequin fetuses. Pediatr Dermatol. 1993;10:214–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1993.tb00365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama M, Yoneda K, Kim S-Y, Koyama H, Shimizu H. Cornified cell envelop proteins and keratins are normally distributed in harlequin ichthyosis. J Cutan Pathol. 1996;23:571–575. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1996.tb01452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama M, Dale BA, Smith LT, Shimizu H, Holbrook KA. Regional difference in expression of characteristic abnormality of harlequin ichthyosis in affected fetuses. Prenat Diagn. 1998;18:425–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu A, Akiyama M, Ishiko A, Yoshiike T, Suzumori K, Shimizu H. Prenatal exclusion of harlequin ichthyosis; potential pitfalls in the timing of the fetal skin biopsy. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:811–814. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchet-Bardon C, Dumez Y, Labbe F, Lutzner MA, Puissant A, Henrion R, Bernheim A. Prenatal diagnosis of harlequin ichthyosis. Lancet. 1983;1:132. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)91780-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook KA, Smith LT, Elias S. Prenatal diagnosis of genetic skin disease using fetal skin biopsy samples. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:1437–1454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama M, Suzumori K, Shimizu H. Prenatal diagnosis of harlequin ichthyosis by the examinations of keratinized hair canals and amniotic fluid cells at 19 weeks’ estimated gestational age. Prenat Diagn. 1999;19:167–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama M, Holbrook A. Analysis of skin-derived amniotic fluid cells in the second trimester; detection of severe genodermatoses expressed in the fetal period. J Invest Dermatol. 1994;103:674–677. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12398465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams ML, Elias PM. Genetically transmitted, generalized disorders of cornification; the ichthyoses. Dermatol Clin. 1987;5:155–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco RC. Successful treatment of harlequin ichthyosis with acitretin. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:472–484. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2001.01173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haftek M, Cambazard F, Dhouailly D, Reano A, Simon M, Lachaux A, Serre G, Claudy A, Schmitt D. A longitudinal study of a harlequin infant presenting clinically as non-bullous congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:448–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama M, Smith LT, Yoneda K, Holbrook KA, Hohl D, Shimizu H. Periderm cells form cornified cell envelope in their regression process during human epidermal development. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;112:903–909. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama M, Sakai K, Sugiyama-Nakagiri Y, Yamanaka Y, McMillan JR, Sawamura D, Niizeki H, Miyagawa S, Shimizu H. Compound heterozygous mutations including a de novo missense mutation in ABCA12 led to a case of harlequin ichthyosis with moderate clinical severity. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:1518–1523. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama-Nakagiri Y, Akiyama M, Shimizu H. Hair follicle stem cell-targeted gene transfer and reconstitution system. Gene Ther. 2006;13:732–737. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams ML, Hincenbergs M, Holdbrook KA. Skin lipid content during early fetal development. J Invest Dermatol. 1988;91:263–268. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12470400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghunath M, Hennies HC, Ahvazi B, Vogel M, Reis A, Steinert PM, Traupe H. Self-healing collodion baby: a dynamic phenotype explained by a particular transglutaminase-1 mutation. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;120:224–228. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]