Abstract

Purpose

To determine whether the bony architecture of the distal radius and proximal scaphoid have a role in stabilizing the scaphoid, and to determine whether a relationship between the bony geometry measurements and the amount of wrist constraint could be determined.

Methods

Eight cadaver wrists were tested in a wrist joint motion simulator. The level of scapholunate instability after sectioning the scapholunate interosseous, radioscaphocapitate, and the scaphotrapezium ligaments was determined and related to radiographic measurements of volar tilt, lateral tilt (ulnar tilt of the radioscaphoid fossa), the depth of the radioscaphoid fossa, and 6 radii of curvature measurements of the proximal scaphoid and distal radius. The force to dorsally dislocate the scaphoid out of the radioscaphoid fossa was computed.

Results

The radioscaphoid fossa and scaphoid curvatures were larger in those wrists that did not show gross instability after ligamentous sectioning in the wrist simulator. Similarly, those wrists with a deeper radioscaphoid fossa and greater volar tilt were also more stable. The force required to dislocate these wrists was greater than in those wrists that showed gross carpal instability.

Conclusions

This study suggests that the bony anatomy of the radius and scaphoid have a role in stabilizing the carpus after ligament injury. The effect of ligament sectioning on producing carpal instability may be moderated by the bone geometry of the radiocarpal joint. This may explain why some people may have a tear of the scapholunate interosseous ligament but not present with clinical symptoms.

Keywords: Scapholunate instability, wrist, biomechanics

Scapholunate (SL) dissociation can be a disabling injury, typically caused by a fall. With this injury, the scapholunate interosseous ligament (SLIL) and other carpal ligaments may be completely or partially disrupted, allowing instability of the associated carpal bones; however, there is a wide spectrum of injuries and levels of disabilities. In some cases, despite major ligamentous disruption, relatively smooth carpal motion occurs with little carpal instability. In other cases, the scaphoid can dislocate dorsally out of the radial scaphoid (RS) fossa, causing severe pain. Reduction of the joint results in the scaphoid clunking or snapping back into the joint. In either situation, the SLIL may appear torn during the surgical examination. In certain arms, in our previous biomechanical experiments,1–3 we observed little instability of the scaphoid and lunate after sectioning of the SLIL and other ligaments. The kinematics of the bones were changed, but the severity of the instability varied.

The purpose of this study was to determine whether the bony architecture of the distal radius and proximal scaphoid have a role in stabilizing the scaphoid. The hypothesis was that in some wrists the bony geometry of the distal radius helps constrain the scaphoid and lunate, thus preventing instability despite any ligamentous tears. A secondary purpose of this study was to determine whether a relationship between the bony geometry measurements and the level of wrist constraint could be determined.

Materials and Methods

Eight fresh cadaver wrists were moved through cyclic flexion-extension and radioulnar deviation ranges of motion using a dynamic wrist simulator while the 3-dimensional (3D) motions of the scaphoid and lunate were monitored using electromagnetic motion sensors (Fastrak; Polhemus, Colchester, VT).1–4 Carpal kinematic data were acquired with all ligamentous structures intact and after the combined sectioning of the SLIL, the radioscaphocapitate (RSC) ligament, and the scaphotrapezium (ST) ligament. After ligamentous sectioning, 3 levels of carpal instability were defined (Table 1), minimal, intermediate, or gross, based on visual examination of the gap between the scaphoid and lunate and if the scaphoid would clunk back into the RS fossa.

Table 1.

Scapholunate Instability: 3 Qualitative Levels

| Minimal | Little or no SL gap, no scaphoid clunk |

| Intermediate | SL gap present during part of wrist motion, no scaphoid clunk |

| Gross | SL gap present and either scaphoid clunk, or scaphoid riding up to and down from the dorsal rim of radius, or scaphoid riding up and staying on dorsal rim of radius |

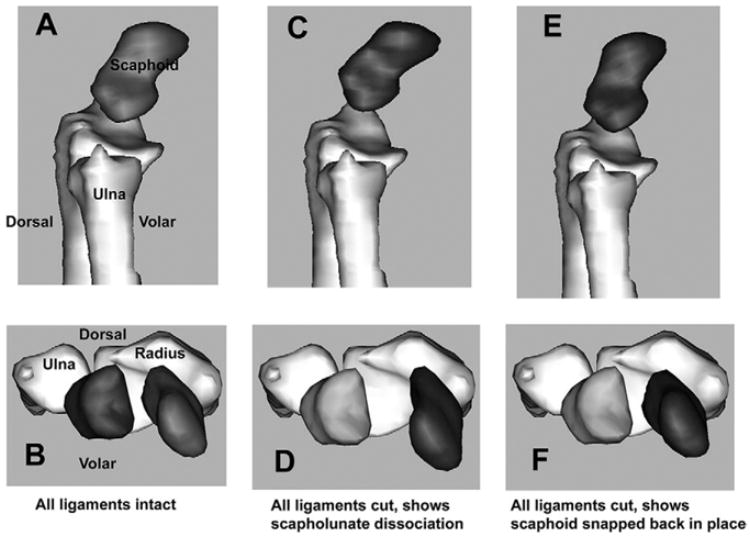

After the 3 ligaments were sectioned, each wrist had a computed tomography (CT) scan. By combining the resultant surface models of the scaphoid and lunate with the corresponding kinematic data, animations of the scaphoid and lunate were made for each of the 8 arms5 for each of the motions. Dorsal and axial views of the animations were reviewed to aid in quantifying the SL gap in each arm before and after ligament sectioning. The animations also showed whether during the motion, after ligamentous sectioning, the scaphoid snapped back into the radioscaphoid joint, defined as scaphoid clunk (Fig. 1). The animation models were exported into computer-aided design (CAD) software (Solidworks; Solid-works Corp., Concord, MA) to aid in making bone geometry measurements. Because of how the CT scans were thresholded, the CAD models do not include cartilage.

Figure 1.

Scaphoid clunk. (A) Lateral view of the scaphoid at 20° of wrist extension with the wrist moving from neutral to extension, with all ligaments intact. (B) Corresponding transverse plane view of the scaphoid shown in (A). (C) Lateral view of the same scaphoid with the wrist at 20° extension, but with the SLIL, RSC, and ST ligaments sectioned. The scaphoid has flexed, moved dorsally, and radially compared to the intact state, and is now on the dorsal rim of the radius. (D) Corresponding transverse view of the scaphoid shown in (C). As the wrist and scaphoid continue to extend, the scaphoid “snaps” back into the radioscaphoid fossa, approximately 0.04 seconds later in the cadaver wrist motion: (E) lateral view; (F) corresponding transverse view.

The bony geometry was quantified by examining posteroanterior (PA) and lateral radiographs, and from the CAD models of the bones. The radiographs were taken with the arm in 90° of elbow flexion, at neutral forearm rotation, and with the wrist in neutral flexion/extension and radioulnar deviation. The beam was centered over the wrist joint at the junction between the proximal carpal row and the distal radius, and between the radioscaphoid and radiolunate fossas. The volar tilt of the radioscaphoid fossa was measured on the lateral radiograph. It is the angle between a line drawn perpendicular to the long axis of the radius and a line connecting the dorsal and volar rims of the radioscaphoid fossa. The ulnar tilt of the radioscaphoid fossa as viewed in the frontal plane was measured on the PA radiograph. It is the angle between a perpendicular to the long axis of the radius and a line connecting the radial styloid and the ridge between the radioscaphoid and radiolunate fossas. The depth of the RS fossa was measured on the PA radiograph. It is the height of the radial styloid above the lowest point in the RS fossa and is measured as the distance between 2 perpendicular lines to the long axis of the radius, one tangential to the distal tip of the radial styloid and the other to the most proximal point of the RS fossa.

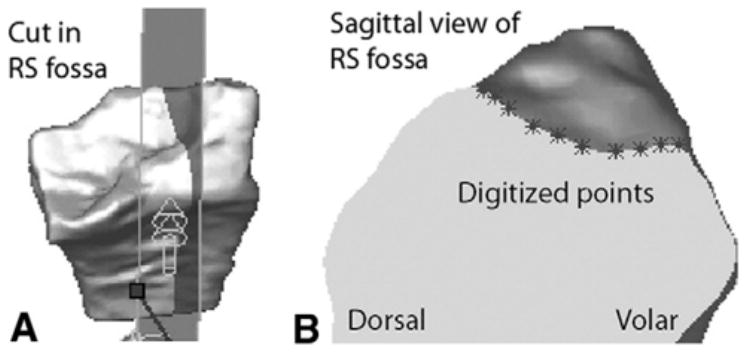

By using the 3D CAD models, 3 sagittal plane and 3 coronal plane radii of curvatures of the scaphoid and distal radius were determined. The curvatures in the sagittal plane were determined by making a virtual cut in the CAD model in the sagittal plane at the middle of the RS fossa (Fig. 2). Similarly for the coronal plane, a virtual slice was made in the middle of the RS fossa. On the sectioned view of each plane, the approximate region of articulation between the scaphoid and radius was identified. The coordinates of approximately 10 points (minimum, 6) on those portions of the scaphoid and radius were recorded and used in a nonlinear curve fit program (NLREG; Sherrod, Brentwood, TN) to determine the corresponding radii of curvatures. The radius of curvature is the curvature of a circle fit to those points. A larger radii of curvature in general is indicative of a flatter articulating surface; however, because the radii of curvature is computed for only part of a circle (representing the articulating surface), a larger radius of curvature may not be related to a less-deep RS fossa. These are 2 independent measurements. In fact, there can be 2 articulating surfaces with equivalent RS depths, but with different curvatures. The surface having a larger curvature would have a longer chord connecting the edges of the partial circle representing the joint surface than the other surface with a smaller radius of curvature.

Figure 2.

The RS fossa radius of curvature computation. (A) Three-dimensional CAD model showing a virtual sagittal plane cut in the distal radius though the RS fossa. (B) Sagittal plane section showing the RS fossa surface and points located on the surface from which the radii of curvature is determined.

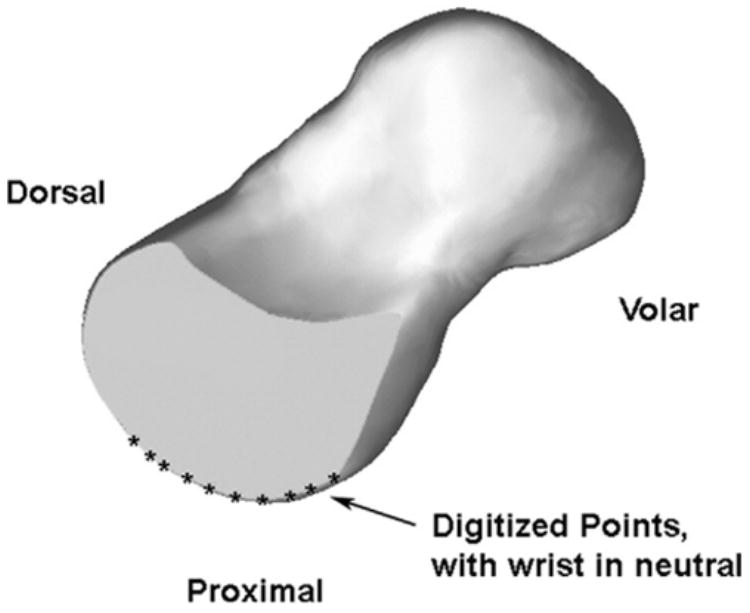

In the sagittal plane, the portions of the scaphoid visualized as articulating with the RS fossa with the wrist in neutral and in 45° of flexion were used. Thus, in the sagittal plane, the curvature of the RS fossa (Fig. 2) and 2 curvatures for the scaphoid were determined (Fig. 3). In the coronal plane, the curvature of the scaphoid articulating with the RS fossa with the wrist in neutral was computed. Also in the coronal plane, 2 curvatures of the RS fossa were determined, first the coronal plane curvature at the center of the fossa and then the coronal plane curvature on the volar rim of the RS fossa.

Figure 3.

Scaphoid sagittal plane curvature computation. Sagittal plane section showing the result of a virtual cut through the scaphoid and the points located on the surface from which the radii of curvature is determined.

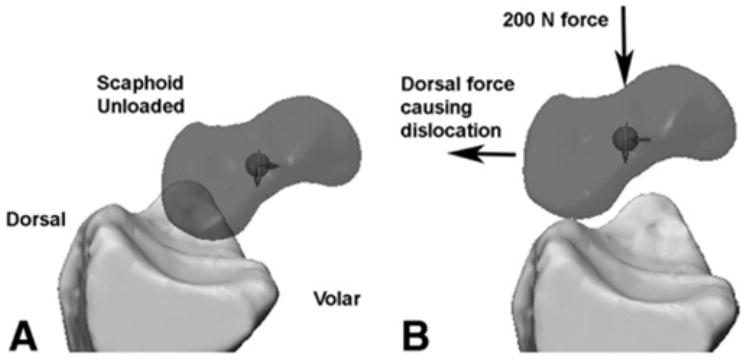

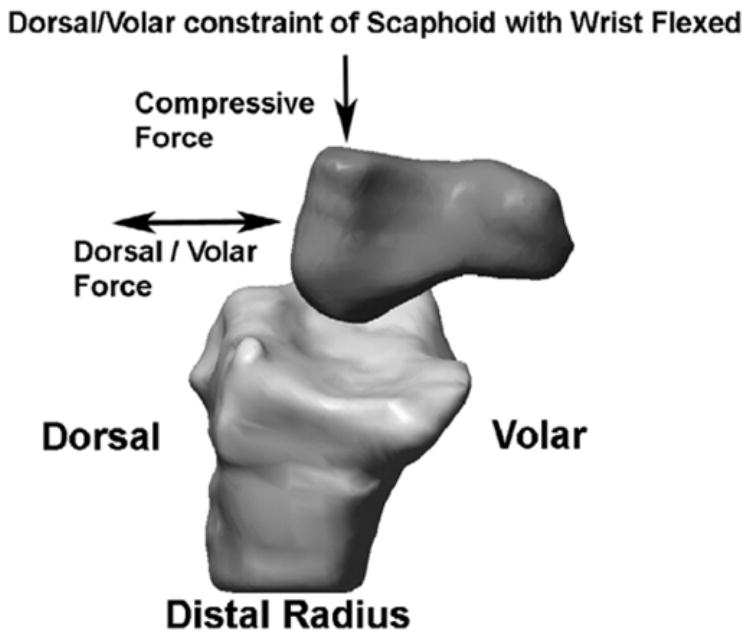

To characterize the mechanical level of constraint for the scaphoid, first the force needed to dislocate the scaphoid dorsally out of the RS fossa was computed with the wrist in neutral and then in 48° of wrist flexion. The CAD models of the radius and scaphoid, based on the animated models at the corresponding wrist positions, were incorporated into a 3D dynamic simulation software package (Visual Nastran 4D; MSC Software Corp., Santa Ana, CA). The software allows one to apply external forces to an object and quantify the resultant motion. An example would be determining the force needed to pull a car tire out of a hole. Because the CT scans of the bones did not include cartilage, the scaphoid was lowered onto the radius until contact was made. Material properties were selected to simulate cartilage (modulus of elasticity, 0.7 MPa; Poisson’s ratio, 0.1; coefficient of friction, 0.01). In this study, only the role of the bony architecture in preventing dislocation was examined. No soft-tissue constraints were included. First, for each arm, at each wrist position, the dorsally directed force needed to cause a dorsal dislocation of the scaphoid was determined by gradually increasing the dorsal force, while a 200 N compressive and proximally directed force was applied to simulate wrist grip (Fig. 4). Dislocation was defined as the position when the scaphoid rose up to the top of the dorsal rim of the distal radius. Second, the dorsal/volar constraint for each scaphoid was determined by applying a 50 N dorsal force and then a 50 N volar force to the scaphoid, while maintaining the 200 N axial compressive force (Fig. 5). The sum of the resultant dorsal and volar motions of the scaphoid was measured and defined as the dorsal/volar constraint. In these models, scaphoid motion was constrained to translations in the sagittal plane and measured for each type of load.

Figure 4.

Determination of the dislocation force of the scaphoid. (A) Sagittal view of the radius and scaphoid under no compressive or dorsal loading. (B) Scaphoid has dislocated and is sitting on the dorsal rim of the radius. A 200 N compressive force was applied to simulate wrist grip.

Figure 5.

Determination of the dorsal/volar constraint of the scaphoid. After a 200 N compressive force was applied to simulate wrist grip, first a 50 N dorsal force and then a 50 N volar force was applied. The displacement of the scaphoid as a result of the 50 N dorsal force was summed with the displacement of the scaphoid as a result of the 50 N volar force to compute the dorsal/volar constraint of each scaphoid.

Results

With respect to the radiographic measurements (Table 2), after ligamentous sectioning those wrists with a deeper RS fossa and a greater volar tilt have a scaphoid that is less likely to ride up the dorsal rim of the distal radius during wrist motion. The amount of ulnar tilt does not seem to be a factor that is related to scapholunate instability after ligamentous sectioning.

Table 2.

Bone Geometry Measurements From Radiographs

| Level of Instability

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimal (n = 3) | Intermediate (n = 3) | Gross (n = 2) | |

| Depth of RS fossa, mm (SD) | 10.3 (1.2) | 9.8 (1.4) | 8.6 (0.1) |

| Volar tilt,° (SD) | 17.8 (2.5) | 15.3 (1.8) | 8.5 (0.7) |

| Ulnar tilt,° (SD) | 20.2 (1.4) | 19.5 (1.7) | 21.5 (3.5) |

With respect to the bone geometry measurements made from the 3D models of the scaphoid and distal radius (Table 3), after ligamentous sectioning those wrists with a larger radius of curvature in both the sagittal and coronal planes for the RS fossa and the scaphoid seem to be less likely to become unstable than those with smaller curvatures. Visually, these arms were observed to have a smaller SL gap and did not show scaphoid clunk. In all of the forearms, the sagittal scaphoid curvature was smaller on the proximal/volar surface (average, 3.7 mm; SD, 0.7 mm), corresponding to when the scaphoid was in flexion as compared with its proximal/dorsal surface (average, 7.6 mm; SD, 2.1 mm), corresponding to when the scaphoid was in neutral.

Table 3.

Bone Geometry Measurements From 3D Models

| Level of Instability

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Radii of Curvature Measurements | Minimal (n = 3) | Intermediate (n = 3) | Gross (n = 2) |

| Sagittal plane: RS fossa, mm (SD) | 12.0 (1.1) | 8.9 (1.8) | 7.9 (2.0) |

| Sagittal plane: scaphoid with wrist in neutral, mm (SD) | 9.1 (2.4) | 7.0 (2.0) | 6.3 (1.2) |

| Sagittal plane: scaphoid with wrist in flexion, mm (SD) | 4.1 (0.8) | 3.4 (0.5) | 3.3 (0.8) |

| Coronal plane: RS fossa (in center of fossa), mm (SD) | 18.2 (3.5) | 18.7 (3.9) | 11.4 (2.9) |

| Coronal plane: RS fossa (on the volar rim), mm (SD) | 16.8 (0.7) | 15.3 (2.8) | 11.4 (2.9) |

| Coronal plane: Scaphoid with wrist in neutral, mm (SD) | 8.2 (1.8) | 6.6 (3.8) | 6.5 (0.3) |

The force to cause the scaphoid to dislocate dorsally out of the RS fossa was computed to be greater in those wrists that were observed to be minimally unstable after ligamentous sectioning, regardless of whether these forces were computed with the wrist in flexion or in neutral (Table 4). The smallest forces required to cause the scaphoid to dislocate were when the wrist was in flexion and observed to be grossly unstable. In a similar way, when the wrist was in a neutral flexion/extension position, those wrists that were found to be grossly unstable were determined to allow the most dorsal/volar displacement caused by a 50 N dorsal and then a 50 N volar force (Table 5).

Table 4.

Force to Dorsally Dislocate the Scaphoid

| Level of Instability

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimal (n = 3) | Intermediate (n = 3) | Gross (n = 2) | |

| Dislocation force, wrist in flexion, N (SD) | 508 (426) | 260 (33) | 163 (124) |

| Dislocation force, wrist in neutral, N (SD) | 639 (319) | 343 (78) | 407 (132) |

Table 5.

Total Scaphoid Dorsal/Volar Displacement Caused by Dorsal and Then Volar Forces

| Level of Instability

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimal (n = 3) | Intermediate (n = 3) | Gross (n = 2) | |

| Displacement, wrist in flexion, mm (SD) | 3.3 (4.1) | 0.8 (0.7) | 3.8 (4.3) |

| Displacement, wrist in neutral, mm (SD) | 0.4 (0.4) | 1.6 (0.7) | 4.2 (3.6) |

Discussion

Scapholunate instability may be manifested by a gap between the scaphoid and lunate, by irregular motion of the scaphoid such that it moves dorsally up the distal radius as the wrist moves from flexion into extension, and by changes in the motion between the scaphoid and lunate. In the unstable carpus, the relatively smaller sagittal distal radius of curvature of the scaphoid when it is flexed may allow for it to be less constrained and permit it to move up the dorsal radius out of its normal articulating surface. As the scaphoid starts to reach extension, however, the now larger scaphoid radius of curvature reduces the amount of allowed laxity and may cause the scaphoid to clunk back into its normal articulation on the radius. The occurrence of gross instability in patients with torn SLILs, RSC ligaments, and ST ligaments may be less if their distal radius has a greater volar tilt and a deeper RS fossa such that the scaphoid is less likely to ride up the inclination. The occurrence of gross instability in patients with ligamentous injury also may occur less in the presence of a larger coronal curvature of the RS fossa. A larger coronal curvature may allow some scaphoid dorsal motion but then allow the scaphoid to slide back into the RS fossa without a clunk.

Limitations of this study included its small sample size, which prevented a statistical analysis. Another limitation was that the bone geometry curvature measurements did not reflect the inclusion of cartilage. Therefore, the computed curvature measurements underestimate the actual curvatures. One concern is whether one might interpret these results as suggesting that larger wrists with presumably larger sagittal and coronal radii of curvatures would in general be less likely to be grossly unstable after ligamentous injury. There probably is an interaction between the scaphoid and RS fossa curvatures that determines the level of resultant instability and warrants further investigation.

A further limitation of this study was the limited angular positions at which the curvatures were determined and the dislocation forces computed. Other positions during wrist flexion-extension or other wrist motions might help in better understanding how the scaphoid is constrained by the distal radius. We chose the 45° wrist flexion position because at this angle it appeared to us that after ligamentous sectioning, the scaphoid frequently would dissociate from the lunate and, in some wrists, the scaphoid would dislocate. A 30° wrist flexion position possibly would be better. We chose the neutral wrist position because in many wrists the scaphoid had reduced by this angle as the wrist was coming out of wrist flexion. We wanted to see if this reduction was related to the geometry and could be related to the computed dislocation force. We chose the wrist flexion-extension motion because the scaphoid rarely dislocated during wrist radioulnar deviation. A gap frequently would occur, but the scaphoid would not dislocate.

Some of the bone geometry measurements were performed on plain radiographs whereas others were computed from 3D CAD models. Initially we sought to determine if radiographs would be sufficient to quantify the bony geometry of the proximal scaphoid and distal radius and relate it to scapholunate instability. Later we decided to add CT scan curvature measurements.

The concept of scapholunate instability being related to bony geometry has not been previously discussed in the literature. It has been shown by cadaver dissection, however, that 28% of the elderly population have an incidental tear of the SLIL.6 This suggests to us that a tear of the SLIL may occur without resultant instability, perhaps because of the bony architecture. This lends support to the current study in which we suggest that in some patients the SLIL injury may not develop into a static instability pattern because of the geometry of these bones.

Acknowledgments

Supported by extramural research from the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (grant R49/CCR216814) from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (grant 1R01 AR050099).

Footnotes

The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

References

- 1.Short WH, Werner FW, Green JK, Masaoka S. Biomechanical evaluation of the ligamentous stabilizers of the scaphoid and lunate: part II. J Hand Surg. 2005;30A:24–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2004.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Short WH, Werner FW, Green JK, Weiner MM, Masaoka S. The effect of sectioning the dorsal radiocarpal ligament and insertion of a pressure sensor into the radiocarpal joint on scaphoid and lunate kinematics. J Hand Surg. 2002;27A:68–76. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.2002.30074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Short WH, Werner FW, Green JK, Masaoka S. Biomechanical evaluation of ligamentous stabilizers of the scaphoid and lunate. J Hand Surg. 2002;27A:991–1002. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.2002.35878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Werner FW, Palmer AK, Somerset JH, Tong JJ, Gillison DB, Fortino MD, Short WH. Wrist joint motion simulator. J Orthop Res. 1996;14:639–646. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100140420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Green JK, Werner FW, Wang H, Weiner MM, Sacks JM, Short WH. Three dimensional modeling and animation of two carpal bones: a technique. J Biomech. 2004;37:757–762. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Viegas SF, Patterson RM, Hokanson JA, Davis J. Wrist anatomy: incidence, distribution, and correlation of anatomic variations, tears, and arthrosis. J Hand Surg. 1993;18A:463–475. doi: 10.1016/0363-5023(93)90094-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]