Abstract

Little is known at present about the relation between parental and child cytokine profiles. In this study we aimed to investigate the cytokine profile of 2-year-old children and their corresponding mothers, 2 years after delivery. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated from IgE-sensitized (n = 15) and non-sensitized (n = 58) 2-year-old children and their mothers. The responses to ovalbumin, cat and phytohaemagglutinin (PHA) were investigated using the enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISpot) technique. Interferon (IFN)-γ-, interleukin (IL)-4-, IL-10- and IL-12-producing cells were enumerated. At 2 years of age, IgE-sensitized children exhibited increased numbers of IL-4-producing cells in response to PHA and also showed an increase in IL-10- and IL-12-producing cells to allergen that was more pronounced in response to ovalbumin than to cat. A statistically significant increase in the numbers of IFN-γ-, IL-10- and IL-12-producing cells to the allergens, but not to PHA, was found in the mothers of IgE-sensitized children irrespective of their own atopic status. IgE levels and cytokine responses were correlated between the mothers and their children, indicating that cytokine responses to both allergen and PHA might be governed by genetic factors. We speculate that the increased cytokine response to allergen, as opposed to the allergic status of the mother, might be a better predictor and/or a risk factor for the child to develop IgE-sensitization in early life.

Keywords: atopy, childhood, cytokine, IgE, mother–child correlation

Introduction

It has been suggested that even in utero an atopic mother can affect the fetus to develop into a T helper type 2 (Th2)-responding phenotype, which potentially could lead to an increased risk for the development of early atopy in the child [1]. In line with this hypothesis, our group have previously shown that cord blood mononuclear cells (CBMC) obtained from children born to atopic mothers have a more Th2-skewed cytokine profile, i.e. an increased interleukin (IL)-4 to interferon (IFN)-γ ratio and lower numbers of IL-12-producing cells than CBMC obtained from children born to non-atopic mothers [2]. In a follow-up study, when the same children were evaluated on basis of their immunoglobulin E (IgE)-sensitization status at the age of 2 years, our data revealed that there was no correlation between an increased cord blood IL-4 : IFN-γ ratio and the development of early atopy [3]. Rather, our data showed that children developing early IgE-sensitization had fewer IL-12-producing CBMC compared to their non-sensitized counterparts. The numbers of IL-12-producing CBMC were well correlated with the numbers of IFN-γ-producing cells, indicative of a depressed Th1-type response in the cord blood of children who develop early atopy [3].

Several studies have shown that children who develop atopy have a defect in their CBMC IFN-γ production [4–7]. However, what is less clear is whether the depressed Th1 responses remain depressed during early childhood. Thus, some studies have revealed depressed IFN-γ responses [8], whereas others have shown that IFN-γ responses are increased [9–11] in young atopic children compared to their non-atopic counterparts.

In this study we hypothesize that at 2 years of age there is already a difference in cytokine profiles between IgE-sensitized and non-sensitized children. Based on the fact that not only children with atopic parents become IgE sensitized, we also hypothesize that mothers of IgE-sensitized children have a cytokine profile different from that of mothers of non-sensitized children and that this, through genetic inheritance, could govern the cytokine profile of their offspring and thus affect the development of early IgE-sensitization.

Materials and methods

Subjects

The subjects included in this study were originally recruited for a prospective heredity study, which has been described elsewhere [2]. Seventy-three pregnant women and their husbands were consecutively recruited at the maternity ward. The recruited parents were either healthy or had a clinical history of rhino conjunctivitis and/or asthma against furred pets and/or pollen. Depending on the parental atopy status three study groups were established − double family history (dh), where both parents were allergic, maternal family history (mh), where only the mother was allergic and no family history (nh), where none of the parents were allergic. The clinical history was confirmed with a positive or a negative skin-prick test (SPT), and only the parents where the SPT confirmed the clinical history were invited to participate in the study.

All infants were born at hospitals in the Stockholm area, were full term (≤ 37 weeks of gestation), had birth weights within the normal range (Table 1) and were healthy postnatally. The Human Ethics Committee at Huddinge University Hospital approved the study, and the parents provided informed consent.

Table 1.

Demographic data of the children. Data are presented as percentages of the group or median and (range). There were no statistical differences in the demographic data between IgE-sensitized and non-sensitized children.

| IgE-sensitized | Non-sensitized | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender, % | ||

| Female | 53 | 55 |

| Family history, % | ||

| Double | 40 | 28 |

| Maternal | 20 | 43 |

| None | 40 | 29 |

| Obstetric data | ||

| Gestational age, weeks | 40 (38–43) | 40 (37–43) |

| Birth weight, g | 3575 (2455–4640) | 3608 (2680–4530) |

| Maternal age, years | 32·0 (27–44) | 32·0 (22–44) |

| Paternal age, years | 33·0 (26–39) | 33·0 (22–50) |

| Mode of delivery, % | ||

| Vaginal | 93 | 93 |

| Caesarean section | 6·7 | 6·9 |

| Exposure | ||

| Month of birth, % | ||

| April–September | 47 | 41 |

| October–March | 53 | 59 |

| Breastfeeding, months | ||

| Exclusive | 4·5 (0–6) | 4·0 (0–9) |

| Partial | 8·0 (0–24) | 9·0 (1–24) |

| Smokers, % | ||

| Mother | 0 | 8·6 |

| Father | 27 | 11 |

| Pets at home, % | ||

| Cat | 6·7 | 10 |

| Dog | 0 | 10 |

| No of siblings, % | ||

| 0 | 67 | 43 |

| 1 | 33 | 48 |

| ≥ 2 | 0 | 8·6 |

| Attending day care, % | 67 | 74 |

| Age at day care start, months | 18·0 (14–24) | 18·0 (12–25) |

In this study the mothers and the children were divided on basis of the IgE-sensitization status of the children 2 years after delivery. IgE-sensitization was defined as having either a positive SPT and/or having allergen-specific IgE in plasma at the age of 2 years. It is well known that SPT and serologically measured allergen-specific IgE antibodies do not always correlate [12,13], especially not in small children who predominantly have IgE antibodies against food allergens [13]. Based on these facts, we decided to include both SPT-positive children and children having allergen-specific IgE antibodies in the sensitized group.

Skin-prick testing

The same nurse performed all the SPT against food and inhalant allergens according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (ALK, Copenhagen, Denmark). Children were tested for: cow’s milk (3% fat, standard milk), egg white [Soluprick (ALK Sverige AB, Sweden) weight to volume ratio 1 : 100], soy bean protein (Soja Semp®, Semper AB, Stockholm, Sweden), cod fish (Soluprick, 1/20), peanut (Soluprick, 1/20), cat, dog, birch, timothy grass and Dermatophagoides farinae (all Soluprick, 10 HEP). The allergens used for the parents were: birch, cat, dog, horse, Artemesia vulgaris (mugwort), rabbit, timothy grass and, if required, moulds (Alternaria and Cladosporium) and D. farinae (all Soluprick 10 HEP). Histamine chloride (10 mg/ml) and the allergen diluent were used as the positive and negative controls, respectively. A positive SPT was defined as having a weal reaction ≥ 3 mm after 15 min.

Allergen-specific IgE determination

Allergen-specific IgE in plasma from the 2-year-old children and their mothers was determined by the ImmunoCAP® method (Pharmacia Diagnostics AB, Uppsala, Sweden). For the children the same 10 allergens were used for the ImmunoCAP® analyses as for the SPT. Mothers were tested using four different allergens: cat dander, dog dander, timothy grass and birch pollen. An allergen-specific IgE level ≥ 0·35 kU /l was considered positive.

Total IgE was measured in plasma by the ImmunoCAP® IgE fluorescence enzyme immunoassay (FEIA) method (Pharmacia Diagnostics AB, detection limit 2·0 kU/l) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Blood/plasma collection and preparation of mononuclear cells

Blood samples were collected in heparinized tubes from the non-pregnant mothers and the children 2 years after delivery. Plasma was stored at −20°C pending analysis. Mononuclear cells were obtained through Ficoll-Paque (Pharmacia-Upjohn, Stockholm, Sweden) gradient centrifugation and the cells were frozen gradually at 1°C/min to −70°C in a freezing container (Nalgene Cryo 1°C, Nalgene Company, NY, USA) and were then stored in liquid nitrogen until analyses were made. Cells were frozen at 1–2 × 107 cells per ml of tissue culture media (TCM, RPMI-1640 HEPES containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS) and 25 µg/ml of gentamicin and 2 mm l-glutamine), supplemented with 10% dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO). Cryopreservation has previously been shown not to affect cytokine production or proliferation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) [10,14].

After thawing, cells were tested for viability with trypan blue exclusion. The viability was greater than 90% for all samples assayed. The cells were then pre-stimulated for 4 h in round-bottomed 5 ml polystyrene tubes at 106 cells/ml of TCM with or without allergen or phytohaemagglutinin (PHA) in concentrations previously shown to induce IL-4 and IFN-γ production [15]. The allergens used were Aquagen SQ cat extract (8 kU/ml, ALK-Abelló, Hørsholm, Denmark) or sterile filtered ovalbumin (10 µg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich Sweden AB, Stockholm, Sweden). PHA (1 µg/ml, Murex Diagnostics Ltd, Dartford, UK) was used as a positive control. The pre-stimulated cells were then used in the enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISpot) assay.

Quantification of cytokine secretion

The reverse ELISpot assay, mainly as described by Gabrielsson and colleagues [15], was used for quantification of the numbers of cytokine-secreting cells. Briefly, 100 µl of coating antibodies was added to 96-well nitrocellulose plates (Millipore Corp., Bedford, MA, USA) at 10 µg/ml in sterile filtered carbonate buffer (pH 9·6). Monoclonal antibodies used for coating were M-450 for IL-4 (Endogen, MA, USA), 1-D1K for IFN-γ, IL-12-I for IL-12 and 9D7 for IL-10 (all from Mabtech AB, Nacka, Sweden).

Plates were incubated overnight at +4°C and washed six times with filtered phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7·2). In the last washing step the PBS was sucked through the membrane with a vacuum control machine (Millipore Corp.) and 100 µl of the pre-stimulated PBMC (105 or 2 × 104 cells for IFN-γ after PHA stimulation) were added to the wells in triplicate, and the plates were then incubated for 40–42 h at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Cells were then washed away with PBS and 100 µl of biotinylated antibodies (12·1 for IL-4, 7-B6-1 for IFN-γ, IL-12-II for IL-12 or 12G8 for IL-10, all purchased from Mabtech AB) were added at a concentration of 1 µg/ml and incubated for 4 h at room temperature (RT). After another set of washings, the plates were incubated at RT for 90 min with streptavidine–alkaline–phosphatase (Mabtech AB) diluted 1 : 1000 in PBS. The plates were then washed again and 100 µl of BCIP/NBT substrate solution (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA, USA) was added and the plates were incubated at RT until dark spots emerged on the membrane. The plates were washed with tap water to stop the development. After development the plates were dried and spots were counted using a computerized ELISpot counter (Autoimmun Diagnostika GmbH, Strassberg, Germany).

All the patients were tested for all cytokines and all stimuli. In order to minimize the possible effect of intra-day assay differences the samples were assayed in groups containing one mother–child pair from each of the three family history groups (described in the ‘Subjects’ section) at each assay occasion.

Statistical analysis

The numbers of cytokine-producing cells are presented as median numbers per 105 PBMC if not stated otherwise. For all data presented, background levels have been subtracted. Because of the non-normal distribution of the sample data and the low number of samples the Spearman’s rank correlation test was used for correlations, and for between-group comparisons the Mann–Whitney U-test was used. For comparing non-numerical frequency data the coded χ2 test was used. Wilcoxon’s signed-rank test was used to test for differences between responses within the same individual. Statistical significance was defined as a P-value lower than 0·05.

Results

IgE-sensitization

Fifteen of the 73 2-year old children (21%) in the study had allergen-specific IgE and/or a positive SPT towards at least one of the allergens tested for. These children constitute the IgE-sensitized group, among whom 13 were sensitized against food allergens and four were sensitized against animal dander and/or pollens. Fifty-eight children (79%) had neither allergen-specific IgE nor positive SPT and constitute the non-sensitized group. There were no statistically significant differences in the demographic data between the IgE-sensitized and the non-sensitized groups of children, as shown in Table 1.

The mothers were divided into two groups depending on the IgE-sensitization status of the child at the age of 2 years. There were no statistically significant differences in the frequencies of allergic symptoms (asthma, rhinitis and conjunctivitis) in the mothers between the two groups; nor were there any statistically significant differences in the frequencies of sensitization against animal danders or pollen (Table 2). However, there was a tendency, although non-statistically significant, for more symptoms and sensitization among mothers of IgE-sensitized children.

Table 2.

Allergy status of the mothers. Data are presented as percentages of the group or median and (range). There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups.

| Mothers of IgE-sensitized children | Mothers of non-sensitized children | |

|---|---|---|

| Total IgE, kU/l | 73 (3·71–2001) | 36·5 (2·64–1121) |

| SPT positivity, % | 80 | 58 |

| sIgE, % | 80 | 55 |

| Asthma, % | 40 | 22 |

| Rhinitis, % | 60 | 47 |

| Conjunctivitis, % | 47 | 45 |

Total IgE levels

As expected, the levels of total IgE were significantly higher in the IgE-sensitized children compared to the non-sensitized children (49·9 (range 7·03–647) versus 13·2; range (1·9–314), P < 0·001). The allergic mothers had significantly higher total IgE levels than the non-allergic mothers (P< 0·001). When the mothers were divided into mothers of IgE-sensitized children and mothers of non-sensitized children, there was no significant difference in the total IgE levels (Table 2), although there was a tendency for elevated levels in the mothers of IgE-sensitized children. The log total IgE levels were statistically significantly correlated between the mothers and the children (P< 0·01, rs = 0·33).

Cytokine-producing cells in the 2-year-old children

IFN-γ

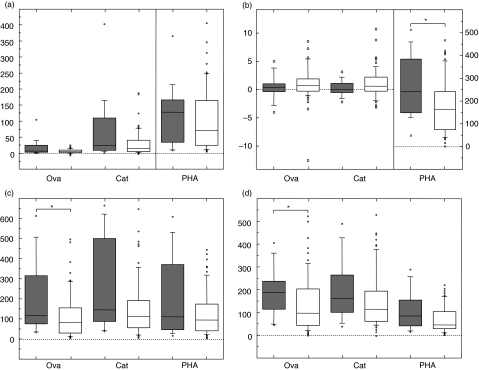

In the 2-year-old children the number of spontaneously IFN-γ-producing cells were 2·0 per 105 PBMC. All the responses were significantly different from zero, although after ovalbumin stimulation the responses were close to zero for both the sensitized and the non-sensitized children. There were no statistically significant differences in the numbers of IFN-γ-producing cells after any of the stimulations between the two groups of children (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

Numbers of interferon (IFN)-γ- (a), interleukin (IL)-4- (b), IL-10- (c) and IL-12- (d) producing cells per 105[or 2 × 104 for IFN-γ after phytohaemagglutinin (PHA)] peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) in the IgE-sensitized (filled boxes) and non-sensitized children (empty boxes) after ovalbumin (ova), cat and PHA stimulation. The line within the box represents the median (50th percentile) and the bottom and top edges represent the 25th and 75th percentiles. The whiskers extend to the 10th and 90th percentiles and values below and above the 10th and 90th percentiles are represented by open circles. *0·05 > P ≥ 0·01.

IL-4

There were no IL-4-producing cells in the medium control and all the responses were significantly different from zero, although there were very few IL-4-producing PBMC in response to allergen. In response to PHA the numbers of IL-4-producing cells were statistically significantly higher in the IgE-sensitized children compared to the non-sensitized children (P< 0·05, Fig. 1b). Following allergen or PHA stimulation, no statistically significant differences in the IL-4 : IFN-γ ratios between the sensitized and the non-sensitized children could be found (data not shown).

IL-10

The background level of IL-10-producing cells was 15·0 per 105 PBMC. The IgE-sensitized 2-year-old children had higher numbers of IL-10-producing cells than the non-sensitized children after stimulation with ovalbumin (P< 0·05, Fig. 1c). After cat and PHA stimulation there were no statistically significant differences. IL-10 : IL-4 ratios were higher in the IgE-sensitized children after ovalbumin (P< 0·05) and cat (P< 0·05) stimulation, but not after PHA stimulation (data not shown).

IL-12

The background level of IL-12-producing cells in the medium control was 1·7 per 105 PBMC. There was a tendency for more IL-12-producing cells after all stimuli (statistically significant for ovalbumin, P < 0·05) in the IgE-sensitized group compared to the non-sensitized group (Fig. 1d).

Cytokine-producing cells in the mothers

IFN-γ

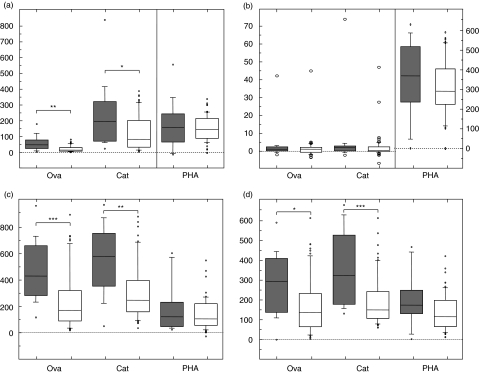

The medium control gave a median number of 13·3 IFN-γ-producing cells per 105 PBMC for the mothers and all the responses were statistically significantly higher than background levels. For the stimulated cells there was a general trend showing statistically significantly higher numbers of IFN-γ-producing cells after antigen stimulation in the mothers of the IgE-sensitized children than mothers of non-sensitized children (Fig. 2a). However, the differences were statistically significant only after ovalbumin (P< 0·01) and cat (P< 0·05), but not after the mitogenic PHA stimulation.

Fig. 2.

Numbers of interferon (IFN)-γ- (a), interleukin (IL)-4- (b), IL-10- (c) and IL-12- (d) producing cells per 105[or 2 × 104 for IFN-γ after phytohaemagglutinin (PHA)] peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) in the mothers of the IgE-sensitized (filled boxes) and non-sensitized children (empty boxes) after ovalbumin (ova), cat and PHA stimulation. For explanation of the box plot model see legend to Fig. 1. *0·05 > P ≥ 0·01; **0·01 > P ≥ 0·001; ***0·001 > P.

IL-4

For the mothers there were no spots in the IL-4 medium control. The numbers of IL-4-producing PBMC after all stimuli were significantly different from zero, although the responses were low after allergen stimulation. In response to PHA the numbers of IL-4-producing PBMC were slightly, although not statistically significantly, higher in the mothers of the IgE-sensitized children than in the mothers of the non-sensitized children (Fig. 2b). There were no statistically significant differences in the IL-4 : IFN-γ ratios between the mothers of IgE-sensitized and non-sensitized children (data not shown).

IL-10

In the medium control there was a median number of 29·3 IL-10-producing cells per 105 PBMC. Also for IL-10 there were more PBMC producing this cytokine in the mothers of the IgE-sensitized children than in the mothers of the non-sensitized children (Fig. 2c). Statistically significant differences were seen after ovalbumin (P< 0·001) and cat (P< 0·01) stimulation. For PHA the difference was not statistically significant. IL-10 : IL-4 ratios were higher in the mothers of IgE-sensitized children after both ovalbumin (P< 0·01) and cat (P< 0·05) stimulation. There was no difference after PHA stimulation (data not shown).

IL-12

The median number of IL-12-producing cells in the maternal medium control was 4·0 per 105 PBMC. The numbers of IL-12-producing cells after allergen stimulation was higher in the mothers of the IgE-sensitized children than in the mothers of the non-sensitized children (Fig. 2d). Statistically significant differences were seen after ovalbumin and cat stimulation (P< 0·05 and P < 0·01, respectively), but not after PHA stimulation.

Correlations between cytokine responses in mothers and children

The numbers of cytokine-producing cells were statistically significantly correlated between the mothers and their children (Table 3). This was true for all the cytokines (in the case of IL-4 only after PHA stimulation, as the numbers of cytokine-producing cells in response to allergen were close to zero). When the children were divided into IgE-sensitized and non-sensitized groups, the correlations in the numbers of cytokine-producing cells between the mothers and the children were statistically significant for the non-sensitized group (data not shown). Despite the low number of individuals, in the IgE-sensitized group the correlations were statistically significant or close to statistically significant in all cases (data not shown).

Table 3.

Correlation between maternal and child cytokine responses. Data are presented as P-values and (correlation coefficients, rs).

| IFN-γ | IL-4 | IL-10 | IL-12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spontaneous | < 0·001 | < 0·001 | < 0·001 | < 0·001 |

| (0·61) | (0·75) | (0·56) | (0·74) | |

| Ovalbumin | < 0·001 | n.s. | < 0·001 | < 0·001 |

| (0·56) | (0·15) | (0·63) | (0·71) | |

| Cat | < 0·001 | n.s. | < 0·001 | < 0·001 |

| (0·40) | (0·14) | (0·50) | (0·46) | |

| PHA | < 0·01 | < 0·001 | < 0·01 | < 0·001 |

| (0·38) | (0·44) | (0·37) | (0·53) |

IFN: interferon; IL: interleukin; PHA: phytohaemagglutinin. n.s. = statistically non-significant.

Discussion

In this study, elevated numbers of IL-4 producing cells could be seen after PHA stimulation in 2-year-old IgE-sensitized children compared to their non-sensitized counterparts. An increase in the numbers of both IL-10- and IL-12-producing cells, which was more evident for ovalbumin than for cat allergen, could also be observed in the IgE-sensitized children. Our data also revealed that the mothers of the IgE-sensitized children had a general exacerbation of cytokine-producing cells, which was more evident in response to allergen than to PHA. In this study we also observed correlations between the maternal and the child responses, although the samples were taken 2 years after delivery.

Most studies on adult atopic individuals have revealed Th2-skewed immune responses to a number of stimuli. It has also been shown that newborns with a high risk of becoming atopic already have a Th2-skewed immune response to allergen [4,16] and mitogen [17] in their cord blood. Despite the dogma that allergic individuals have a general skewing towards Th2, many studies on young atopic children have revealed a mixed Th1/Th2 type of response upon allergen stimulation [9–11,18,19], suggesting that allergen responses during the first years of life become Th1/Th2 balanced, but exacerbated in atopic children compared to healthy children. Some studies even report Th1-skewed cytokine responses to allergen in atopic children, while some mitogenic stimuli have been suggested to result in Th2-skewed responses in young atopic individuals [20]. Hence, it is important to differentiate between allergen and mitogen responses, as they may not necessarily be the same with regard to Th1/Th2 balance [20]. In concordance with the reports suggesting that young atopic individuals respond to allergen with a mixed Th1/Th2 response [9–11,18,19], our study revealed elevated numbers of IL-4 and, to some extent, IFN-γ producing cells after PHA stimulation in the IgE-sensitized children.

Our data also revealed elevated numbers of IL-12- and IL-10-producing cells in the IgE-sensitized children which was more pronounced for the food allergen ovalbumin than for cat allergen. The most probable reason for this discrepancy is that hen’s egg allergy is an early but short-lived and non-persistent allergy that children outgrow [18], whereas responses to cat develop late and are more persistent. Thus it is evident that cytokine profiles may differ not only between mitogen and allergen, but may also vary depending on the allergen.

In this study, we also investigated the cytokine profiles of the mothers of the children with regard to the IgE-sensitization status of their children. The rationale behind this is the fact that not only children with a family history of atopy become IgE-sensitized, but also children with non-atopic parents. To our knowledge there are few, if any, other studies investigating the difference between mothers of IgE-sensitized children and mothers of non-sensitized children with regard to PBMC cytokine profiles. Our data show that the mothers of IgE-sensitized children, irrespective of their own atopic status, possess elevated numbers of IFN-γ-, IL-10- and IL-12-producing cells to allergen compared to the mothers of the non-sensitized children, whereas the PHA responses did not differ significantly between the groups. The reasons for the observed differences are not known but may indicate, as suggested by others [21,22], that the atopic status of the mother may not be as important as the actual response to stimuli in the mother. One of the predominant risk factors for the development of IgE-sensitization and atopic disease is considered to be genetic, and many variants in genes coding for cytokines [23], but also other factors such as sex hormones [24,25], have been described that alter cytokine production. In our study there were also more allergic mothers in the group of mothers of IgE-sensitized children, which may have affected the result. Thus, we can only speculate so far about the reasons behind these differences and the effects it might have on the offspring.

IL-10 has been ascribed the property of being a down-regulatory cytokine. In our study, IL-10 was produced in higher levels in IgE-sensitized children and their mothers and it is hence tempting to speculate that high IL-10 could be a way for the immune system to depress the deleterious response that an atopic reaction represents. Another possibility is that the IgE-sensitized children and their mothers might be unable, or at least less able, to respond to IL-10-mediated signalling. IL-10 : IL-4 ratios have been suggested to govern the decision between a healthy and an allergic immune response [26]. Our data show that the IgE-sensitized children and their mothers had significantly higher ratios than non-sensitized children and their mothers. IL-10 is produced by, among other cells, regulatory T-cells (Tregs) [27]. In this study we did not phenotype the IL-10-producing cells, so we do not know if our IL-10-producing cells are Tregs or other cells. Thus, further studies are needed to elucidate our findings.

The cytokine and IgE correlations between the child and maternal responses seen in this study could be the result of mother and child living in the same environmental setting. Despite this, we believe that differences in environment are less likely to explain the differences seen between the mothers of the IgE-sensitized children and the mothers of the non-sensitized children, as there were no demographic differences between the study groups. It is also hard to see environmental factors that would coincide for this group of mothers that would result in the observed differences. By running three mother–child pairs, one from each of the three family history groups, at each assay occasion we have minimized the possibility of intra-day variations being the cause of the differences.

Taken together, we believe that genetic inheritance and possibly environmental factors are important contributors to the development of IgE-sensitization, and that the cytokine response pattern of the mother, rather than allergy status, might be the link between maternal and child atopy. This might explain why also children with no atopic parents become IgE-sensitized. However, further studies are needed to clarify the issue and also consider the paternal responses. We are currently trying to relate child responses to those of both their mother and their father.

Acknowledgments

Vetenskapsrådet, the Vårdal-, the Asthma and Allergy- and Konsul THC Berg foundations supported this study financially. We would like to thank Ann Sjölund, Margareta Hagstedt, Anna-Stina Ander and Monica Nordlund for excellent technical assistance, Pharmacia Diagnostics AB for supplying reagents for most of the plasma IgE-analyses and Mabtech AB for providing antibodies and ELISpot counting facilities. We are also endlessly grateful to all the families willing to participate in the study.

References

- 1.Jones CA, Holloway JA, Warner JO. Does atopic disease start in foetal life? Allergy. 2000;55:2–10. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2000.00109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gabrielsson S, Soderlund A, Nilsson C, Lilja G, Nordlund M, Troye-Blomberg M. Influence of atopic heredity on IL-4-, IL-12- and IFN-gamma-producing cells in in vitro activated cord blood mononuclear cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 2001;126:390–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2001.01703.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nilsson C, Larsson AK, Hoglind A, Gabrielsson S, Troye Blomberg M, Lilja G. Low numbers of interleukin-12-producing cord blood mononuclear cells and immunoglobulin E sensitization in early childhood. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:373–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.01896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prescott SL, Macaubas C, Smallacombe T, et al. Reciprocal age-related patterns of allergen-specific T-cell immunity in normal vs. atopic infants. Clin Exp Allergy. 1998;28(Suppl. 5):39–44. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.1998.028s5039.x. discussion 50–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kondo N, Kobayashi Y, Shinoda S, et al. Reduced interferon gamma production by antigen-stimulated cord blood mononuclear cells is a risk factor of allergic disorders − 6-year follow-up study. Clin Exp Allergy. 1998;28:1340–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.1998.00418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tang ML, Kemp AS, Thorburn J, Hill DJ. Reduced interferon-gamma secretion in neonates and subsequent atopy. Lancet. 1994;344:983–5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91641-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martinez FD, Stern DA, Wright AL, Holberg CJ, Taussig LM, Halonen M. Association of interleukin-2 and interferon-gamma production by blood mononuclear cells in infancy with parental allergy skin tests and with subsequent development of atopy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1995;96(5)(Part 1):652–60. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(95)70264-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noma T, Yoshizawa I, Aoki K, Yamaguchi K, Baba M. Cytokine production in children outgrowing hen egg allergy. Clin Exp Allergy. 1996;26:1298–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holt PG, Rudin A, Macaubas C, et al. Development of immunologic memory against tetanus toxoid and pertactin antigens from the diphtheria–tetanus–pertussis vaccine in atopic versus nonatopic children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:1117–22. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.105804. 6 Part 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Macaubas C, Sly PD, Burton P, et al. Regulation of T-helper cell responses to inhalant allergen during early childhood. Clin Exp Allergy. 1999;29:1223–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.1999.00654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kimura M, Tsuruta S, Yoshida T. Unique profile of IL-4 and IFN-gamma production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells in infants with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;102:238–44. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(98)70092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pierson-Mullany LK, Jackola DR, Blumenthal MN, Rosenberg A. Evidence of an affinity threshold for IgE-allergen binding in the percutaneous skin test reaction. Clin Exp Allergy. 2002;32:107–16. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-0477.2001.01244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Julge K, Vasar M, Bjorksten B. Development of allergy and IgE antibodies during the first five years of life in Estonian children. Clin Exp Allergy. 2001;31:1854–61. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2001.01235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ausiello CM, Lande R, Urbani F, et al. Cell-mediated immune responses in four-year-old children after primary immunization with acellular pertussis vaccines. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4064–71. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.8.4064-4071.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gabrielsson S, Paulie S, Rak S, et al. Specific induction of interleukin-4-producing cells in response to in vitro allergen stimulation in atopic individuals. Clin Exp Allergy. 1997;27:808–15. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.1997.560878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rinas U, Horneff G, Wahn V. Interferon-gamma production by cord-blood mononuclear cells is reduced in newborns with a family history of atopic disease and is independent from cord blood IgE-levels. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 1993;4:60–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.1993.tb00068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pohl D, Bockelmann C, Forster K, Rieger CH, Schauer U. Neonates at risk of atopy show impaired production of interferon-gamma after stimulation with bacterial products (LPS and SEE) Allergy. 1997;52:732–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1997.tb01230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ng TW, Holt PG, Prescott SL. Cellular immune responses to ovalbumin and house dust mite in egg-allergic children. Allergy. 2002;57:207–14. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2002.1o3369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kimura M, Yamaide A, Tsuruta S, Okafuji I, Yoshida T. Development of the capacity of peripheral blood mononuclear cells to produce IL-4, IL-5 and IFN-gamma upon stimulation with house dust mite in children with atopic dermatitis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2002;127:191–7. doi: 10.1159/000053863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smart JM, Kemp AS. Increased Th1 and Th2 allergen-induced cytokine responses in children with atopic disease. Clin Exp Allergy. 2002;32:796–802. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2002.01391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bottcher MF, Jenmalm MC, Garofalo RP, Bjorksten B. Cytokines in breast milk from allergic and nonallergic mothers. Pediatr Res. 2000;47:157–62. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200001000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoppu U, Kalliomaki M, Laiho K, Isolauri E. Breast milk − immunomodulatory signals against allergic diseases. Allergy. 2001;56(Suppl. 67):23–6. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2001.00908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tariq SM, Matthews SM, Hakim EA, Stevens M, Arshad SH, Hide DW. The prevalence of and risk factors for atopy in early childhood: a whole population birth cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;101:587–93. doi: 10.1016/S0091-6749(98)70164-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saito S. Cytokine network at the feto–maternal interface. J Reprod Immunol. 2000;47:87–103. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0378(00)00060-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Balzano G, Fuschillo S, Melillo G, Bonini S. Asthma and sex hormones. Allergy. 2001;56:13–20. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2001.00128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akdis M, Verhagen J, Taylor A, et al. Immune responses in healthy and allergic individuals are characterized by a fine balance between allergen-specific T regulatory 1 and T helper 2 cells. J Exp Med. 2004;199:1567–75. doi: 10.1084/jem.20032058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robinson DS, Larche M, Durham SR. Tregs and allergic disease. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1389–97. doi: 10.1172/JCI23595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]