Abstract

Previous studies of an experimental human immunoglobulin preparation for intravenous use, containing normal pooled IgM (IVIgM), have shown its beneficial therapeutic effect in experimental autoimmune diseases. The mechanisms of its immunomodulatory activity remain however, poorly understood. In the experiments reported here, IVIgM inhibited the proliferation of various autonomously growing human lymphoid cell lines in vitro, as well as of MLR- and of PHA-stimulated human T-lymphocytes. These effects of IVIgM were observed at non-apoptotic concentrations and were stronger on a molar basis than those of normal pooled IgG for intravenous use (IVIg). Both preparations, when administered to SCID mice, repopulated with human peripheral blood mononuclear cells, delayed the expression of the early activation marker CD69 on both human CD4+ and CD8+ T-lymphocytes, activated by the mouse antigenic environment. The data obtained show that normal pooled human IgM exerts a powerful antiproliferative effect on T-cells that is qualitatively similar but quantitatively superior to that of therapeutic IVIg. Our results suggest that infusions with IVIgM might have a significant beneficial immunomodulating activity in patients with selected autoimmune diseases.

Keywords: autoimmunity, immunotherapy, IVIg, IgM, SCID mice

Introduction

Previous stuidies have shown that the antigen-binding activity of natural IgG autoantibodies in disease-free humans and in mice is controlled by IgM [1–3]. This control may be deficient in some patients with autoimmune diseases [4,5]. The importance of circulating IgM for the control of autoimmunity was confirmed in a recent study on autoimmune-prone MRL/lpr mice that had been genetically manipulated to produce only the membrane form, but not the secreted form of IgM. These animals developed higher levels of IgG anti-native DNA antibodies, more severe glomerulonephritis and had a shorter lifespan, as compared to unmanipulated lupus-prone MRL/lpr mice. Further, normal non-autoimmune animals that were rendered unable to produce the secreted form of IgM, spontaneously developed IgG anti-double stranded DNA autoantibodies suggesting a potential role for natural IgM antibodies in regulating pathological autoimmune process [6,7]. This prompted us to examine the immunomodulatory role of natural human IgM.

A normal pooled intravenous immunoglobulin M (IVIgM) that meets the prerequisites for therapeutic immunoglobulin preparations for intravenous use was conceived. Preliminary studies have shown that the IVIgM preparation inhibited the binding of disease-associated IgG autoantibodies to their target self-antigen and suppressed the disease activity of experimental autoimmune uveoretinitis in rats [1]. We showed previously that IVIgM suppressed the level of human anti-acethylcholine receptor antibodies and prevented the loss of muscle acethylcholine receptors in experimental myasthenia gravis in immunodeficient SCID mice, repopulated with thymocytes from a myasthenia gravis patient [8]. The mechanisms, responsible for the observed beneficial immunomodulatory activity of this type of immunoglobulin treatment remain poorly understood.

Our present results show that IVIgM inhibits the proliferation of all studied autonomously growing human lymphoid cell lines and of mitogen- and MLR-activated normal T cells. These data further strengthen the therapeutic potential of pooled normal human IgM in certain immunopathological conditions.

Materials and methods

Immunoglobulin preparations

Normal therapeutic intravenous immunoglobulin G (IVIg, Sandoglobulin) was kindly provided by Novartis, Basel, Switzerland.

Normal pooled human IgM (IVIgM) was prepared by Laboratoire Francaise du Fractionnement et des Biotechnologies (LFB, Les Ulis, France). It was produced by fractionation of pooled plasma from more than 2500 healthy donors using a modified Deutsch-Kistler-Nitschmann ethanol fractionation protocol, followed by octanoic acid precipitation and two ion-exchange chromatography steps [1]. It contained more than 90% IgM, as well as serum albumin, IgA, IgG and small amounts of other serum proteins. Human serum albumin was obtained from the same source. The protein concentration of the preparations was determined spectrophotometrically at 280 nm.

The immunoglobulin preparations were dialysed overnight under sterile conditions against 50 volumes of tissue culture medium described below and supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum before adding them to the in vitro cultured cells.

Cell lines, MLR- and PHA-stimulation of T lymphocytes

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), obtained from healthy adult donors, were stimulated in vitro (105 cells in 0·1 ml of medium per well) by PHA (1 µg/ml, from Gibco, Gaithersbourg, MD, USA) in 96-well tissue culture plates at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator. In all experiments described here RPMI-1640 medium, supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine, 50 U/ml penicillin, 50 mg/ml streptomycin and 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (Deutscher, Strassbourg, France) was used. Mixed lymphocyte reaction was set up by mixing 105 freshly isolated PBMC from one donor with the same number of irradiated (2000 rad) cells from an unrelated donor and culturing them in a volume of 0·1 ml. Four hours after the start of the cultivation, increasing amounts of the immunoglobulin preparations, diluted in medium, were added to quadruplicate wells in a volume of 0·1 ml and the plates were left for another 92 h. Human serum albumin was used as a negative control. Ninety-six hours later 1 µCi 3H-thymidine was added to each well and the cells were harvested after 18 h. 3H-thymidine incorporation was measured with an LKB-Wallac Betaplate liquid scintillation counter.

The M061 human/mouse heterohybridoma producing a human monoclonal IgG antibody, specific for the pp65 kD matrix antigen of human cytomegalovirus was kindly provided by Dr M. Ohlin, Lund University, Sweden [9]. The human T cell line CEM, the B lymphoblastoid line Raji, the promonocytic cell line MM6 and the myelomonocytic HL60 line were obtained from ATCC. Increasing amounts of IVIgM, of IVIg or of a mixture of both were added to quadruplicate wells, containing 104 of the respective cells to a final volume of 0·2 ml. In the later case, the highest dose of IVIgM was mixed with the highest dose of IVIg, the second highest with the second highest, etc. Three days later 3H-thymidine was added and its incorporation was measured as described above.

Assay for apoptosis

Expression of phosphatidylserines was determined by staining CEM cells cultured for 24 h in the presence of increasing concentrations of IVIgM or of the IgM fraction isolated from the serum of a patient with Waldenstrom’s disease. At the end of the mentioned period the cells were washed with binding buffer and stained with Annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide using the Annexin V-FITC apoptosis detection kit (BD Biosciences Pharmingen, San Jose, CA, USA). The samples were analysed using a FACSCanto flow cytometer and FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences).

A second culture plate with CEM cells treated for 24 h as described above was used to measure the effect of the two studied IgM preparations on CEM cell proliferation by 3H-thymidine incorporation.

Animals

Six to 10-week-old female C.B.-17 scid/scid (SCID) mice were obtained from IFFA CREDO (L’Abresle, France) and kept under sterile conditions. The mice were tested for leakiness by the supplier and re-tested by us. The animals were bled from the retro-orbital plexus before the humanization and later at weekly intervals as mentioned below. The levels of human IgM, IgG and IgA in their sera were determined by a sandwich ELISA against standard curves obtained from reference preparations (from Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA)

Groups of female SCID mice (52 animals in all experiments) were injected intraperitoneally with 108 peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), obtained from a healthy human adult blood donor. On the next day the animals were injected with a single dose (400 mg/kg) of IVIg, with an equimolar amount of the IVIgM preparation under study (2100 mg/kg) or with human serum albumin (170 mg/kg). Groups of mice were sacrificed on days 4, 7, 14 and 21 after the treatment. Blood was obtained, peritoneal cells were collected and cell suspensions were prepared from the spleen, the thymus and the pooled lymph nodes of individual animals.

The percentage of CD4+ and CD8+ T-lymphocytes expressing the HLA-DR, CD25, CD45RO and CD69 activation markers, of NK cells, of B lymphocytes with immunoglobulin receptors with κ or λ light chains, of CD5+ B-cells and of CD8+CD57+ cells were determined by flow cytometry.

Immunofluorescence analysis

Cells were stained for 30 min in an ice bath with different combinations of FITC- or PE-labelled antibodies to CD3, CD4, CD5, CD8, CD16, HLA-DR, CD45, CD45RO, CD56, CD57 and CD69, washed and the gated viable cells were analysed using a FACScan flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

Results

Antiproliferative effect of IVIgM on PHA- and MLR-stimulated human T cells and on autonomously growing cell lines

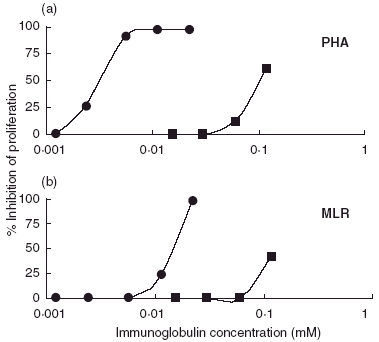

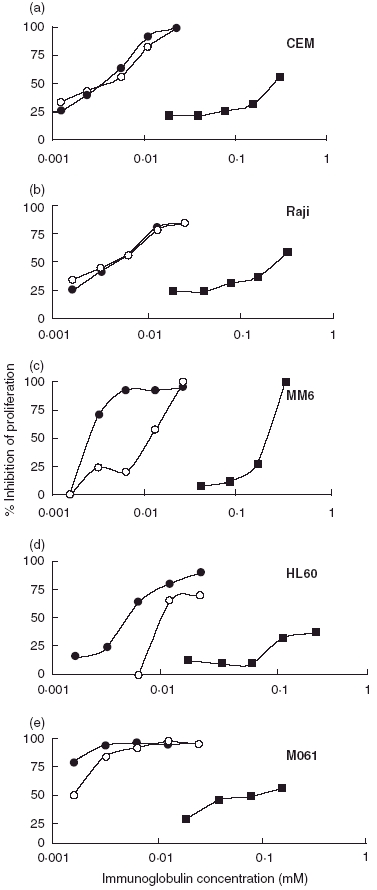

Our experiments confirmed the finding that normal pooled IgG inhibited in a dose-dependent manner the PHA-induced activation of normal human T cells [10]. IVIgM inhibited both the proliferation of mitogen- and allogenic cell-stimulated normal human T lymphocytes (Fig. 1) as well as the proliferation of all studied autonomously growing human haematopoetic cell lines (Fig. 2). Its effects were up to 100 times stronger on a molar basis than those of IVIg. In order to find out if the effects of both immunoglobulin preparations were additive, the cell lines were cultured in the presence of mixtures of increasing concentrations of IVIg plus IVIgM. The antiproliferative activity of both preparations mixed was not higher than that of IVIgM used alone (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Dose-dependent inhibition by IVIgM (•) and by by IVIg (▪) of the (a) PHA- and (b) MLR-induced proliferation of human PBMCs in vitro. The immunoglobulin preparations were introduced four hours after the addition of irradiated allogenic PBMC or after the start of cultivation in the presence of PHA. 3H-thymidine was added 96 h after the start of the cultivation and cells were harvested 18 h later. Stimulation in the presence of 20 mg/ml of HSA (negative control) was calculated as 100% proliferation. The figure shows results from a typical experiment (from at least three independent experiments); each point is the mean of radioactivity of four wells. The SD values of the means were below 10%.

Fig. 2.

Effect of IVIg (▪), of IVIgM (•) and of the mixture IVIg/IVIgM (○) on the proliferation of four spontaneously growing human cell lines (a) CEM (T cell), (b) Raji (B lymphoblastoid), (c) MM6 (promonocytic) (d) the HL60 line (myelomonocytic) and (e) of the human/mouse heterohybridoma M061. 3H-thymidine was added 72 h after the start of the cultivation. For more details see the text to Fig. 1.

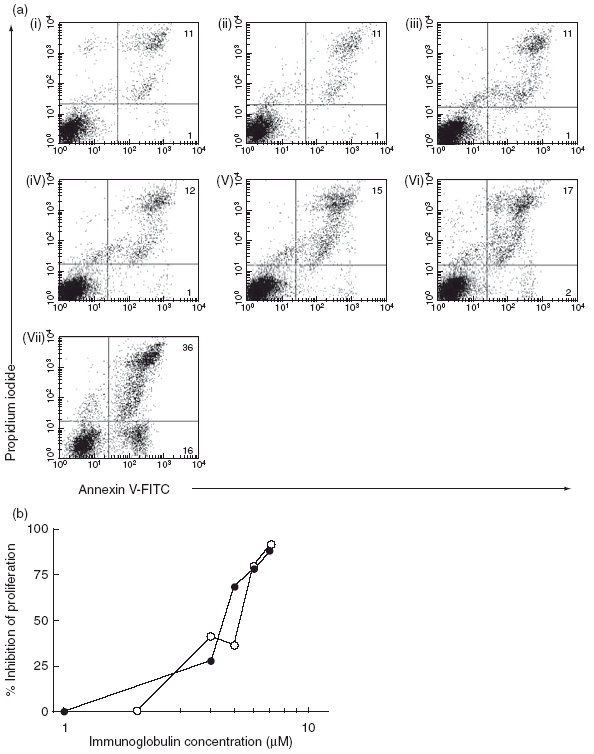

Effects of IVIgM on cell apoptosis

As reported before, CEM T cells cultured in the presence of 0·0125 mM or higher concentration of pooled IgM underwent apoptosis (Fig. 3a, v–vii). while no such effect was observed at lower concentrations of pooled IgM (Fig. 3a, iii,iv). The exposure of the same cells to lower amounts of both IVIgM or of Waldenstrom IgM had a clear-cut effect on their ability to proliferate, which was not due to apoptosis (compare Fig. 3a and b).

Fig. 3.

(a) Annexin-V- staining of CEM T cells cultured for 24 h in: (i) medium only; (ii) 20 mg/ml 0·03 mM human serum albumin; (iii) 0·003 mM IVIgM; (iv) 0·006 mM IVIgM; (v) 0·125 mM IVIgM; (vi) 0·025 mM IVIgM or in (vii) 0·05 mM IVIgM. Cells were double-stained with Annexin-V (FL-1) and with propidium iodide (FL-2) Percentage of stained cells is shown in each dot-plot. (b) Inhibition of the proliferation of CEM cells cultured for 24 h in the presence of increasing concentrations of IVIgM (•) or of Waldenstrom IgM (○) 3H-thymidine was added for the last 18 h of the cultivation.

Effects of IVIgM on in vivo T cell activation

All SCID mice that had been injected i.p. with 108 PBMC, were successfully humanized as indicated by the levels of human immunoglobulins in their sera, up to 2 mg/ml for human IgG. The numbers of recoverable human CD45+ in the peritoneum showed an initial rapid decline in all groups during the first week to less than 2% of the number of cells injected and then remained stable for the period of observation (3 weeks, data not shown). Only cells with an anti-mouse specificity survive longer in the peritoneum of humanized SCID mice [11].

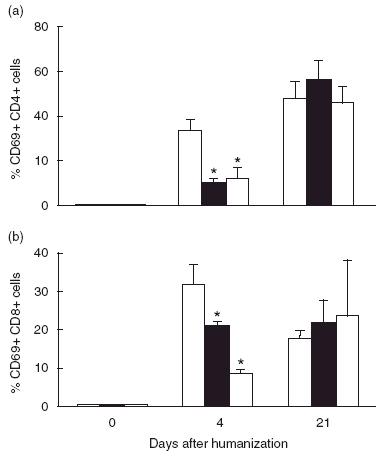

A dramatic rise in all studied activation markers on the human T-lymphocytes was observed during the first week after the i.p. administration of the PBMCs. At day 4 a significant decrease of the percentage of CD69+ CD8 and CD4– positive T cells in IVIg and IVIgM-treated animals was observed (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

IVIgM- and IVIg-treatment of hu-SCID mice delay the expression of the early activation marker CD69 on both human CD4+ (a) and CD8+ (b) T cells, activated by the foreign antigenic environment. Effect of a single dose of 400 mg/kg IVIg (▪), of an equimolar amount of IVIgM (□) or of human serum albumin ( ). *P < 0·05, Kruskall Wallis test.

). *P < 0·05, Kruskall Wallis test.

No differences between the control- and the immunoglobulin-treated animals were detected in the expression of the other activation markers (CD25, HLA-DR and CD45RO) and in the percentage of the other lymphocyte populations studied (data not shown).

When human PBMC were activated in vitro by PHA and cultured in the presence of increasing concentrations of IVIg, IVIgM or serum albumin, four hours later more than 20% of the T lymphocytes were found to express the CD69 early activation marker. No significant differences in its levels were seen, however, between the albumin and immunoglobulin-treated groups (data not shown).

Discussion

The present study tested the effects of a normal pooled human IgM immunoglobulin preparation on cells of the immune system and compared them to the known effects of normal pooled therapeutic human IgG in clinical use for more than 20 years. The data presented here show that IVIgM qualitatively mimics the known in vitro effects of IVIg treatment. However, IVIgM inhibits the proliferation of normal T cells and of haematopoetic cell lines in concentrations that are, on a molar basis, up to two orders lower than those of IVIg.

It is known that the injection of human PBMCs into immunodeficient SCID mice results in the long term survival and chronic activation of the anti mouse-reactive human T lymphocytes [11]. The injection of a single dose of IVIg (400 mg/kg; equal to the dose infused into patients) as well as of an equimolar amount of IVIgM delayed the expression of the early activation marker CD69 on the human T cells in humanized SCID mice. No effect was observed on the other activation markers studied. This suppression in the presence of IVIg and IVIgM was not observed on in vitro PHA-stimulated PBMCs. The similarity between the biological activities of IVIgM and IVIg includes their ability to induce apoptosis in normal human blood cells and in human autonomously growing cell lines [12,13]. While IVIgM induced apoptosis of human cells at a concentration above 0·0125 mM [12], it had an antiproliferative effect at lower concentrations.

The ability of IVIgM to down-regulate in a dose-dependent manner human T- and B-cell functions may suggest that patients with Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia could suffer from different secondary immune-mediated diseases [14–17].

Although the precise stages of the cell-cycle at which the antiproliferative and pro-apoptotic effects of IVIgM may be operating are not elucidated, it is likely that the preparation is effective at various distinct phases. Cross-linking of the B-cell antigen receptor with IgM antibodies initiates a cascade of events that may culminate with proliferation arrest and cell death in B-cells [18] IgM-induced cell death involves a reduction in mitochondrial transmembrane potential during the early phases of induction of apoptosis. Such broad proliferative arrest and pro-apoptotic effect of the preparation may also be related to the interference of IVIgM with essential growth factors and cytokines. Interaction of IVIgM with Fas has been shown to lead to the induction of apoptosis of several cell types [12]. It is likely that IVIgM may also recognize various cytokines as has been shown before for therapeutic IVIg [19,20]. The ability of IVIgM to exert an antiproliferative effect together with its pro-apoptotic activity may be of significance in the therapeutic value of this preparation.

The observed effects of IVIgM could be due to interactions involving either the Fcµ or the F(ab′)2 portions of the IgM molecules as has been shown before for the effects of pooled therapeutic IgG [21]. The anti-inflammatory activity of normal therapeutic IVIg is known to be due at least in part to its binding to the inhibitory FcγRIIb receptor on macrophages [22,23]. Two receptors on human cells that bind Fcµ have been described so far; one is the polymeric immunoglobulin receptor involved in epithelial transport of IgA and IgM and the other is the recently described Fcα/µR [24–28]. Both are present on the surface of a variety of haematopoetic and non-hematopoetic cells, but none of these receptors has been found so far to have an inhibitory activity. A second possibility would be that complexes composed of infused IgM and complement bind to the CR1 (CD35) receptor on human B-cells that has been recently shown to have a suppressive activity [29]. This mechanism could not explain however, our observation on in vitro cultured human cells, as complement was not present in this system.

The observed effects of IVIgM may be due to F(ab′)2- dependent interactions with target molecules on T- and B-cells. A pool of normal IgM may have antibodies with unexpected specificities. For example it has been shown to have antibodies that bind to the NB-p260 antigen on the surface of human neuroblastoma cells and to cause apoptosis therein [30]. Some other mechanisms that are responsible for the suppressive effect of circulating IgM on autoimmunity may include: clearance of circulating self-antigens through the same pathways active in the clearance of bacteria [31], inhibition by idiotypic interactions of the binding of disease-associated IgG autoantibodies to their target self-antigens [1,32] as well as the shaping of the B-cell selection [33] and selection and fine-tuning of the IgG autoantibody repertoire [34,35].

Other beneficial effects of the pooled human IgM described include the promoting of remyelination when administered to mice with chronic Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus-induced demyelinating disease [36,37] and promoting the phagocytosis of E. coli by mononuclear phagocytes in the absence of complement [38]. An experimental IgM-enriched immunoglobulin preparation (containing 70% IgM, 25% IgA and 5% IgG; Biotest Pharma GmbH, Dreieich, Germany) was shown to prevent complement activation in vitro. These results were confirmed in vivo in the rat anti-Thy 1 nephritis model, in which a single dose of IVIgM prevented C3-, C6- and C5b-9 deposition in the rat glomeruli, whereas the effect of IVIg was weak. The reduction of complement deposition was paralleled by a diminished albuminuria, which was absent in the IVIgM-treated animals [39].

An IgM-containing therapeutic human intravenous immunoglobulin preparation (Pentaglobin, containing 12% IgM, 12% IgA and 76% IgG; Biotest Pharma GmbH) has been used for passive immunotherapy for a number of years. It is enriched in antibodies against bacterial antigens [40]. Some clinical studies [41,42], but not others [43] have found it was beneficial in sepsis and in other severe bacterial infections. Pentaglobin was shown to inhibit the MRL reaction in vitro [44] as well as graft-versus-host disease as a part of a five-agent protection regimen in recipients of an unrelated bone marrow [45].

The fact that the highly purified IVIgM preparation under study can profoundly modulate T and B-cell functions may well have clinical implications. Infusions of large doses of IVIg have become in the last two decades a standard immunomodulatory treatment for a number of organ-specific and systemic autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. As the effects of IVIgM on B- and T cell functions are either equal or more potent on molar basis than these of IVIg, we argue that in some selected immunopathological conditions the administration of IVIgM would be still more beneficial, than that of IVIg.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by LFB, Les Ulises, France and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (grant ♯ 55000340). TV is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute International Research Scholar.

References

- 1.Hurez V, Kazatchkine MD, Vassilev T, et al. Pooled normal human polyspecific IgM contains neutrlyzing antiidiotypes to IgG autoantibdies of autoimmune patients and protects from autoimmune disease. Blood. 1997;90:4004–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adib M, Ragimbeau J, Avrameas S, Ternynck T. IgG autoantibody activity in normal mouse serum is controlled by IgM. J Immunol. 1990;145:3807–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Melero J, Tarrago D, Nunez-Roldan A, Sanchez B. Human polyreactive IgM monoclonal antibodies with blocking activity against self-reactive IgG. Scand J Immunol. 1997;45:393–400. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1997.d01-418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stahl D, Lacroix-Desmazes S, Heudes D, Mouthon L, Kaveri SV, Kazatchkine MD. Altered control of self-reactive IgG by autologous IgM in patients with warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Blood. 2000;95:328–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ronda N, Haury M, Nobrega A, Kaveri SV, Coutinho A, Kazatchkine MD. Analysis of natural and disease-associated autoantibody repertoires: anti-endothelial cell IgG autoantibody activity in the serum of healthy individuals and patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Int Immunol. 1994;6:1651–60. doi: 10.1093/intimm/6.11.1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ehrenstein MR, Cook HT, Neuberger MS. Deficiency in serum immunoglobulin (Ig) M predisposes to development of IgG autoantibodies. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1253–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.7.1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boes M, Schmidt T, Chen J. Accelerated Development of IgG autoantibodies and autoimmune disease in the absence of secreted IgM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1184–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vassilev T, Yamamoto M, Aissaoui A, Bonnin E, Berih-Aknin S, Kazatchkine M, Kaveri SK. Normal human immunoglobulin suppresses experimental myasthenia gravis in SCID mice. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:2436–42. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199908)29:08<2436::AID-IMMU2436>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohlin M, Sundquist V-A, Wahren B, Gilliam G, Ruden U, Gombert F, Borrebaeck CAK. Characterisation of human monoclonal antibodies directed against the pp65 kD matrix antigen of human cytomegalovirus. Clin Exp Immunol. 1991;88:508–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Schaik IN, Lundkvist I, Vermeulen M, Brand A. Polyvalent immunoglobulin for intravenous use interferes with cell proliferation in vitro. J Clin Immunol. 1992;12:325–34. doi: 10.1007/BF00920789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tary-Lehmann M, Saxon A, Lehmann PV. The human immune system in hu-PBL-SCID mice. Immunol Today. 1995;16:529–33. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80046-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Varambally S, Bar-Dayan Y, Bayry J, et al. Natural human polyreactive IgM induce apoptosis of lymphoid cell lines and human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Int Immunol. 2004;16:517–24. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prasad NK, Papoff G, Zeuner A, Bonnin E, Kazatchkine MD, Ruberti G, Kaveri SV. Therapeutic preparations of normal polyspecific IgG (IVIg) induce apoptosis in human lymphocytes and monocytes: a novel mechanism of action of IVIg involving the Fas apoptotic pathway. J Immunol. 1998;161:3781–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pilarski LM, Andrews EJ, Serra HM, Ledbetter JA, Ruether BA, Mant MJ. Abnormalities in lymphocyte profile and specificity repertoire of patients with Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia, multiple myeloma, and IgM monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Am J Hematol. 1989;30:53–60. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830300202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jonsson V, Wiik A, Hou Jensen K, et al. Autoimmunity and extranodal lymphocytic infiltrates in lymphoproliferative disorders. J Intern Med. 1999;245:277–86. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1999.0443f.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jonsson V, Kierkegaard A, Salling S, Molander S, Andersen LP, Christiansen M, Wiik A. Autoimmunity in Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinaemia. Leukemia Lymphoma. 1999;34:373–9. doi: 10.3109/10428199909050962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Owen RG, Lubenko A, Savage J, Parapia LA, Jack AS, Morgan GJ. Autoimmune thrombocytopenia in Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia. Am J Hematol. 2001;66:116–9. doi: 10.1002/1096-8652(200102)66:2<116::AID-AJH1026>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marches R, Vitetta ES, Uhr JW. A role for intracellular pH in membrane IgM-mediated cell death of human B lymphomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:3434–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061028998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bendtzen K, Hansen MB, Ross C, Poulsen LK, Svenson M. Cytokines and autoantibodies to cytokines. Stem Cells (Dayt) 1995;13:206–22. doi: 10.1002/stem.5530130303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bayry J, Lacroix-Desmazes S, Delignat S, Mouthon L, Weill B, Kazatchkine M, Kaveri S. Intravenous immunoglobulin abrogates dendritic cell differentiation induced by interferon- present in serum from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthr Rheum. 2003;48:3497–502. doi: 10.1002/art.11346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mouthon L, Kaveri SV, Spalter SH, Lacroix-Desmazes S, Lefranc C, Desai R, Kazatchkine MD. Mechanisms of action of intravenous immune globulin in immune-mediated diseases. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;104(Suppl. 1):3–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Samuelsson A, Towers TL, Ravetch JV. Anti-inflammatory activity of IVIG mediated through the inhibitory Fc receptor. Science. 2001;291:484–6. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5503.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bruhns P, Samuelsson A, Pollard JW, Ravetch JV. Colony-stimulating factor-1-dependent macrophages are responsible for IVIG protection in antibody-induced autoimmune diseases. Immunity. 2003;18:573–81. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakamura T, Kubagawa H, Ohno T, Cooper MD. Characterization of an IgM Fc-binding receptor on human T cells. J Immunol. 1993;151:6933–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Monteiro RC, Van De Winkel JG. IgA Fc receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:177–204. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shibuya A, Sakamoto N, Shimizu Y, et al. Fc alpha/mu receptor mediates endocytosis of IgM-coated microbes. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:441–6. doi: 10.1038/80886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Phillips-Quagliata JM, Patel S, Han JK, et al. The IgA/IgM receptor expressed on a murine B cell lymphoma is poly-Ig receptor. J Immunol. 2000;165:2544–55. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.5.2544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sakamoto N, Shibuya K, Shimizu Y, et al. A novel Fc receptor for IgA and IgM is expressed on both hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic tissues. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:1310–6. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200105)31:5<1310::AID-IMMU1310>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jozsi M, Prechl J, Bajtay Z, Erdei A. Complement receptor type 1 (CD35) mediates inhibitory signals in human B lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2002;168:2782–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.6.2782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.David K, Ollert MW, Vollmert C, Heiligtag S, Eickhoff B, Erttmann R, Bredehorst R, Vogel CW. Human natural immunoglobulin M antibodies induce apoptosis of human neuroblastoma cells by binding to a Mr 260,000 antigen. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3768–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boes M, Prodeus AP, Schmidt T, Carroll MC, Chen J. A critical role of natural immunoglobulin M in immediate defense against systemic bacterial infection. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2381–6. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.12.2381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bar Dayan Y, Bonnin E, Bloch M, Schweitzer R, Ravid M, Kazatchkine MD, Kaveri SV. Neutralization of disease associated autoantibodies by an immunoglobulin M- and immunoglobulin A-enriched human intravenous immunoglobulin preparation. Scand J Immunol. 2000;51:408–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2000.00699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baker N, Ehrenstein MR. Cutting edge. selection of B lymphocyte subsets is regulated by natural IgM. J Immunol. 2002;169:6686–90. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.12.6686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coutinho A, Kazatchkine MD, Avrameas S. Natural autoantibodies. Curr Opin Immunol. 1995;7:812–8. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(95)80053-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kearney JF, Bartels J, Hamilton AM, Lehuen A, Solvason N, Vakil M. Development and function of the early B cell repertoire. Int Rev Immunol. 1992;8:247–57. doi: 10.3109/08830189209055577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bieber A, Asakura K, Warrington A, Kaveri SV, Rodriguez M. Antibody-mediated remyelination: relevance to multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2000;6(Suppl. 2):S1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stangel M, Bernard D. Polyclonal IgM influence oligodendrocyte precursor cells in mixed glial cell cultures: implications for remyelination. J Neuroimmunol. 2003;138:25–30. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(03)00087-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tinguely C, Schaller M, Nydegger UE. Mononuclear cells ingest E. coli opsonized by investigational intravenous immunoglobulin preparations in the absence of complement more efficiently than polymorphonuclear phagocytes. Transfus Apher Sci. 2001;25:43–50. doi: 10.1016/s1473-0502(01)00095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rieben R, Roos A, Muizert Y, Tinguely C, Gerritsen AF, Daha MR. Immunoglobulin M-enriched human intravenous immunoglobulin prevents complement activation in vitro and in vivo in a rat model of acute inflammation. Blood. 1999;93:942–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lissner R, Struff WG, Autenrieth IB, Woodcock BG, Karch H. Efficacy and potential clinical applications of Pentaglobin, an IgM-enriched immunoglobulin concentrate suitable for intravenous infusion. Eur J Surg Suppl. 1999;584:17–25. doi: 10.1080/11024159950188493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pilz G, Appel R, Kreuzer E, Werdan K. Comparison of early IgM-enriched immunoglobulin vs polyvalent IgG administration in score-identified postcardiac surgical patients at high risk for sepsis. Chest. 1997;111:419–26. doi: 10.1378/chest.111.2.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kress HG, Scheidewig C, Schmidt H, Silber R. Reduced incidence of postoperative infection after intravenous administration of an immunoglobulin A- and immunoglobulin M-enriched preparation in anergic patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:1281–7. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199907000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tugrul S, Ozcan PE, Akinci O, Seyhun Y, Cagatay A, Cakar N, Esen F. The effects of IgM-enriched immunoglobulin preparations in patients with severe sepsis [ISRCTN28863830] Crit Care. 2002;6:357–62. doi: 10.1186/cc1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nachbaur D, Herold M, Gachter A, Niederwieser D. Modulation of alloimmune response in vitro by an IgM-enriched immunoglobulin preparation (Pentaglobin) Immunology. 1998;94:279–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1998.00495.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zander AR, Zabelina T, Kroger N, et al. Use of a five-agent GVHD prevention regimen in recipients of unrelated donor marrow. Bone Marrow Transpl. 1999;23:889–93. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]