Abstract

Anti-microbial peptides produced from mucosal epithelium appear to play pivotal roles in the host innate immune defence system in the oral cavity. In particular, human beta-defensins (hBDs) and the cathelicidin-type anti-microbial peptide, LL-37, were reported to kill periodontal disease-associated bacteria. In contrast to well-studied hBDs, little is known about the expression profiles of LL-37 in gingival tissue. In this study, the anti-microbial peptides expressed in gingival tissue were analysed using immunohistochemistry and enxyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Immunohistochemistry revealed that neutrophils expressed only LL-37, but not hBD-2 or hBD-3, and that such expression was prominent in the inflammatory lesions when compared to healthy gingivae which showed very few or no LL-37 expressing neutrophils. Gingival epithelial cells (GEC), however, expressed all three examined anti-microbial peptides, irrespective of the presence or absence of inflammation. Moreover, as determined by ELISA, the concentration of LL-37 in the gingival tissue homogenates determined was correlated positively with the depth of the gingival crevice. Stimulation with periodontal bacteria in vitro induced both hBD-2 and LL-37 expressions by GEC, whereas peripheral blood neutrophils produced only LL-37 production, but not hBD-2, in response to the bacterial stimulation. These findings suggest that LL-37 displays distinct expression patterns from those of hBDs in gingival tissue.

Keywords: ELISA, epithelial cells, neutrophils, periodontal/oral immunology

Introduction

The oral cavity, one of the first entry sites to host pathogenic microorganisms, is potentially protected by the flora of commensal bacteria and anti-microbial peptides. This is especially true for anti-microbial peptides, including the family of histatins, defensins (α-, β- and θ-defensins) and cathelicidin-type peptides (LL-37). These all appear to play important roles in host innate immune defence because of their broad anti-microbial spectrum targeting of Gram-positive to Gram-negative bacteria, as well as fungi and enveloped viruses [1,2]. However, the mode of production and the physiological role of each anti-microbial peptide in the oral cavity are still to be elucidated.

Human β-defensins (hBD-1, hBD-2 and hBD-3) are produced in various types of epithelia [3–5]. LL-37 (CAP-18) is expressed by leucocytes [6] in epithelial cells of the skin [7], the gastrointestinal tract [8] and the respiratory tract [9]. It is reported that expressions of hBD-2 and hBD-3 are inducible by inflammation in various tissues [10–12], whereas hBD-1 is expressed constitutively [12,13]. LL-37 and hBDs possess bactericidal effects on a variety of periodontal pathogenic and cariogenic bacteria [14], as well as oral fungi such as Candida albicans[15]. A cutting-edge study has demonstrated, for example, that the anti-microbial peptide LL-37 is normally present as a defence molecule in saliva, but patients with ‘morbus Kostmann’ syndrome and who, in addition, present with congenital neutropenia, lack the production of LL-37 in saliva [16] and, consequently, are at remarkably increased susceptibility to periodontal disease. Furthermore, LL-37 and hBD-2 possess other biological functions in addition to their anti-microbial effects. To illustrate, the high affinity of LL-37 to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) neutralizes the bioacitivity of LPS and thus protects against endotoxin shock in a murine model of septicaemia [1].

Recent studies using immunohistochemistry have demonstrated the expression of hBD-1 and hBD-2 in the gingival epithelium [17–19]. A variety of bacterial components arereported to induce hBD-2 mRNA expression by primary gingival epithelial cell (GEC) cultures [20,21]. However, the protein and mRNA expression profiles of LL-37 in the gingival tissues remain unclear. In the present study, using polyclonal antibodies specific to hBD-2 and LL-37, we established enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) systems to investigate the quantities of these peptides. Results from ELISA and immunohistochemical analyses have demonstrated that LL-37 displays an expression pattern distinct from hBD peptides in the inflamed gingival tissue.

Materials and methods

Antibodies and synthetic peptides

Synthetic peptides for hBD-1, hBD-2, hBD-3 and LL-37, and all rabbit immune sera to these peptides, have been published previously [22]. Polyclonal IgG specific to hBD-2, hBD-3 and LL-37 were purified from the rabbit immune serum by the Protein-G column purification system (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). A portion of each purified anti-hBD-2 rabbit IgG or anti-LL-37 IgG was biotinylated utilizing an EZ-link Sulfo-NHS-Biotin kit (Pierce) following the manufacturer's instructions.

Gingival tissue samples

Inflamed gingival tissues from patients with periodontal disease (gingival pocket depth > 3 mm, n = 13, four males, nine females, ages 32–58 years) and healthy gingival tissues (gingival pocket depth ≤ 3 mm, n = 10, five males, five females, ages 25–72 years) were collected in laboratories of the Department of Periodontology at the Harvard School of Dental Medicine (HSDM, Boston, MA, USA). The sampled gingival tissues were divided into two portions: a one-half portion of tissue sample was immediately embedded in 22-oxacalcitriol (OCT) compound (Miles, Elkhart, IN, USA) and frozen at −70°C for immunohistochemistry, while the other half was stored in liquid N2 for reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) or for ELISA. Tissue samples for ELISA were pulverized in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) and phenylmetanesulphonyl fluoride (PMSF, Sigma). The institutional review board of HSDM approved the collection of gingival tissues at periodontal surgery and informed consent was obtained from each subject prior to inclusion in this study.

Bacterial culture

Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans JP2, Fusobacterium nucleatum 25586 and Eikenella corrodens 23834 were cultured in trypticase soy broth (Becton Dickinson and Co., Sparks, MD, USA) supplemented with 1% yeast extract (Becton Dickinson) in humidified CO2. Porphyromonas gingivalis 33277 and Prevotella intermedia 25611 were cultured in brain heart infusion broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI, USA) containing hemin (5 mg/l) in humidified CO2. The bacteria growing in broth at mid-log phase were killed by heating at 60°C for 1 h and stocked in PBS (pH 7·2). Although we attempted to use live bacteria for the stimulation of cell culture, proliferation of these anaerobes in cell culture condition [Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), 5% CO2, 37°C] varied between the species. Indeed, it is difficult to interpret whether the difference of bacterial growth is due to anti-microbial peptide produced by GEC or to the mammalian cell culture condition.

Therefore, heat-killed bacteria were employed in this study, so that the same numbers of bacteria are applied to the cell culture. The concentration of bacterial suspensions was checked by optical density at 580 nm.

Culture and stimulation of GEC

Immortalized human gingival epithelial line (OBA-9) and primary culture of GECs were cultured in keratinocyte-serum free medium (SFM) (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA, USA) containing 0·05% bovine pituitary extract (Invitrogen) and 5 ng/ml recombinant epidermal growth factor (Invitrogen) [23]. The OBA-9 cells were kind gift from Drs Shinya Murakami and Yutaka Kusumoto (Osaka University, Japan). The method of establishing an immortalized human gingival epithelial cell (HGEC) line (OBA9) from primary culture by transfection with the simian virus 40 T antigen, together with its resulting characteristics, such as expression of cytokeratine and involucrine, have been published previously [23]. All experiments were carried out when the confluence of epithelial cells was confirmed under a phase contrast microscope. The epithelial cells were incubated in the presence or absence of heat-killed bacteria (105, 106 and 107/ml) in DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and penicillin/streptomycin. The incubation of epithelial cells was stopped at 4 h or 24 h after bacterial stimulation for RT–PCR or ELISA, respectively.

Isolation and in vitro stimulation of human neutrophils

Human neutrophils were isolated from the peripheral blood of healthy volunteers. After lysis of red blood cells with ammonium chloride, neutrophils in the blood sample were isolated by density-gradient centrifugation using Polymorphprep™ (Nycomed Pharma AS, Oslo, Norway) and Histopaque™ (Sigma). Neutrophils were washed with PBS and resuspended in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and antibiotics. In order to examine the bacterial affects on hBD-2 or on LL-37 production by neutrophils, the isolated neutrophils were stimulated with heat-killed bacteria for various periods (6, 12, 24 and 48 h). The culture supernatants were subjected to ELISA for hBD-2 and LL-37.

Immunohistochemistry

Frozen sections (8 µm thickness) of human gingival tissues were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at 4°C for 10 min. Endogenous peroxidase activity was neutralized by incubation of the sections with 3% H2O2 for 10 min. After blocking with 1·5% horse serum in PBS, each section was reacted with polyclonal rabbit IgG specific to hBD-2, hBD-3 or LL-37 overnight at 4°C. Biotin-labelled horse anti-rabbit IgG (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) in the presence of 1·5% horse serum was reacted for 30 min at room temperature, followed by incubation with avidin/biotin complex (ABC) with horseradish peroxidase (Elite ABC kit; Vector Laboratories). Specific staining was performed by colour development with diaminobenzidine substrate in the presence of H2O2 and counterstained with haematoxylin.

RT–PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted from the epithelial cell culture or human gingival tissues using RNA-Bee kit following the manufacturer's protocol (Tel. Test, Friendswood, TX, USA). First-strand cDNA was assembled from 3 µg of sample RNA by Superscript II (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) in the presence of a hexanucleotide mixture (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN, USA). PCR was performed on the resulting cDNA from each sample with specific primers for hBD-2 (5′-AGCCATCAGCCATGAGGGTCTT-3′ 5′-CTGATGAGGGAGCCCTTTCTGAAT-3′); hBD-3 (5′-AGCCTAGCAGCTATGAGGATC-3′ 5′-CTTCGGCAGCATTTTCGGCCA-3′); and LL-37 (5′-ATCATTGCCCAGGTCCTCAG-3′ 5′-GTCCCCATACACCGCTTCAC-3′), and amplified 35 cycles (94°C for 1 min, 60°C for 1 min, 72°C for 1 min and final elongation time for 10 min at 72°C). The resulting PCR products were separated in 1·5% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide. The housekeeping gene β-actin was also included as an internal control.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Purified anti-hBD-2 rabbit IgG or anti-LL-37 rabbit IgG (2 µg/ml; sodium bicarbonate buffer, pH 9·7) was coated onto a 96-well ELISA plate (ICN Biomedicals, Aurora, OH, USA). After blocking each well with 0·5% rabbit serum in PBS supplemented with 0·5% Tween 20, either a cultured medium or a homogenate of gingival tissue samples was applied to the well, followed by purified biotin-conjugated anti-hBD-2 rabbit IgG or biotin-conjugated anti-LL-37 rabbit IgG (8 µg/ml). Each well was then reacted with streptavidin-conjugated horseradish peroxidase (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Colorimetric reactions were developed with o-phenylenediamine (Sigma) in the presence of 0·02% H2O2. Colour development was stopped with H2SO4 (2 N) and measured by an ELISA reader (OD 490 nm). The actual concentration of each anti-microbial peptide was calibrated by referring to a standard curve prepared by serial dilution of control synthetic peptides. Each sample was examined in triplicate wells of a 96-well ELISA plate.

Results

Elevated expression of LL-37 mRNA in inflamed gingival tissues

The total RNA extracted from healthy gingival tissues (n = 4) and inflamed gingival tissues (n = 6) was subjected to the RT–PCR for hBD-2, hBD-3 and LL-37. Positive expressions of mRNA for hBD-2 and hBD-3 were detected in all non-inflamed tissues examined (four of four) (not shown). However, fewer incidences of mRNA expression for hBD-2 or hBD-3 were detected in the inflamed gingival tissues (hBD-2 positive, two of six; hBD-3 positive, three of six) than those found in the healthy tissues. Most importantly, expressions of LL-37 mRNA were expressed only in inflamed tissues (four of six) and not at all in non-inflamed tissues (none of four) (not shown).

Immunohistological evaluation for hBD-2, hBD-3 and LL-37 expressions in gingival tissues

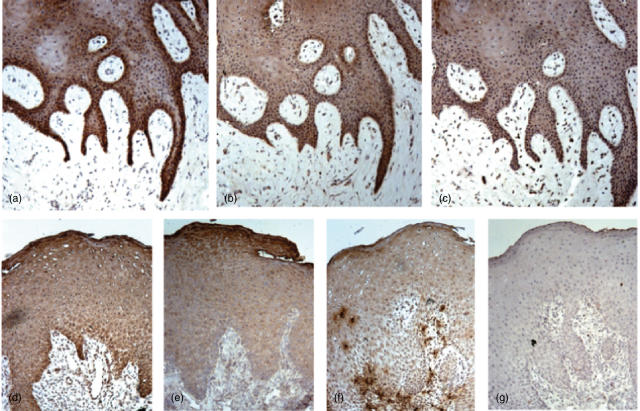

Immunohistochemical staining for anti-microbial peptides, hBD-2, hBD-3 or LL-37, was carried out in the gingival tissue samples. Expressions of all anti-microbial peptides examined were detected in the healthy gingival epithelium, especially in the basal layer (Fig. 1a–c), whereas little or no staining of each anti-microbial peptide was observed in the connective tissue. The expression of hBD-2 and hBD-3 in the epithelium of inflamed tissues showed a similar pattern to the healthy gingivae (Fig. 1d.e). In some inflamed gingival tissues, strong staining of LL-37 was observed on neutrophils infiltrating in both epithelial and connective tissues (Fig. 1f). The staining patterns of each peptide in the different subjects are summarized in Table 1. Although expression patterns for hBD-2 and hBD-3 were similar between healthy (hBD-2, six of six; hBD-3, five of six) and inflamed gingival epithelium (hBD-2, six of six; hBD-3, five of six), the incidences of positive epithelial staining for LL-37 were slightly higher in the inflamed gingival tissues (six of six) than those found in non-inflamed gingival tissues (four of six). LL-37-positive neutrophils were also found in the epithelium and connective tissues of some of the inflamed gingivae (four of six) but not in non-inflamed gingival tissues (none of six).

Fig. 1.

Immunohistochemical analyses of human beta-defensin (hBD)-2, hBD-3 and cathelicidin-type anti-microbial peptide (LL-37) expressions in the gingival epithelium. The gingival tissue was stained with rabbit polyclonal IgG anti-hBD-2 (a, d), anti-hBD-3 (b, e) and anti-LL-37 (c, f). Non-immune normal rabbit IgG was used as negative control (g). These are representative of the results shown in Table 1. (a–c) Non-inflamed sample, subject 2; d–g, inflamed gingival tissue, subject 7. Original magnification × 200.

Table 1.

Expression profiles of human beta-defensin (hBD)-2, hBD-3 and cathelicidin-type anti-microbial peptide (LL-37) in gingival epithelium evaluated by immunohistochemistry.

| Gingival tissue | hBD-2 | hBD-3 | LL-37 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-inflamed (n = 6) | |||

| 1 | + + | + | – |

| 2 | + + | + | + |

| 3 | + | + | + |

| 4 | + + | – | – |

| 5 | + | + | + |

| 6 | + | + | + |

| Inflamed (n = 6) | |||

| 7 | + + | + | + +* |

| 8 | + + | + | + |

| 9 | + + | + | + +* |

| 10 | + + | + | +* |

| 11 | + + | – | + |

| 12 | + + | + | + +* |

–, No obvious staining; +, positive staining in basal layer of epithelium; ++, positive staining in both basal and granular layers.

LL-37 positive neutrophils in epithelium.

Positive correlation between LL-37 expressed in gingival tissues and depth of gingival crevice

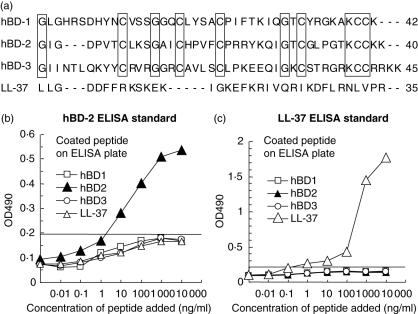

ELISA systems for hBD-2 and for LL-37 were developed using the specific polyclonal antibodies raised againstsynthetic peptides (peptide sequences are shown in Fig. 2a). The hBD family peptides are structurally well conserved because of the six cysteines that compose their β-strand structure, a characteristic of this family of peptides [21]. Based on the ClustalW multiple sequence alignment (Fig. 2a), 25% amino acids were found to be identical among the hBD family of synthetic peptides utilized in this study, and no homology was found between LL-37 and any one of the hBD peptides. Standard curves in ELISA for hBD-2 and for LL-37 showed high specificity to the target peptide, while no cross-reactivity to the other control peptides was detected (Fig. 2b,c).

Fig. 2.

Human beta-defensin (hBD)-2 and cathelicidin-type anti-microbial peptide (LL-37) enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) systems. Peptide sequence alignment among hBD-1, hBD-2, hBD-3 and LL-37 was carried out using a public accessible online algorithm, ClustalW (a). The characters in brackets show identical amino acids detected by ClustalW (a). Standard curves of ELISA for hBD-2 (b) and LL-37 (c) were evaluated by monitoring cross-reactivity to three other control anti-microbial peptides. The cut-off level for hBD-2 or LL-37 was determined at an average ± 2 s.d. of the other three control anti-microbial peptides at 1000 ng/ml or 100 ng/ml, respectively. The lower detection levels for hBD-2 or LL-37 in this particular experiment was 2·5 ng/ml or 0·3 ng/ml, respectively.

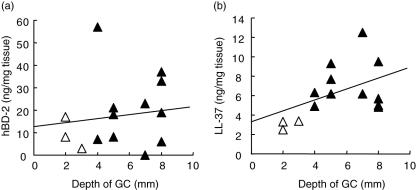

Using these ELISA formats, concentrations of hBD-2 and LL-37 were measured in the homogenates of gingival tissues collected from various depths of the gingival crevice, which is a clinical parameter of periodontal disease [24]. The concentration of hBD-2 did not show any trends in relation to the depth of gingival crevice (Fig. 3a). However, the concentration of LL-37 was correlated positively with the depth of gingival crevice (Fig. 3b), indicating that LL-37 expression in the gingival tissue is associated with the severity of periodontal disease.

Fig. 3.

Protein concentrations of human beta-defensin (hBD)-2 and cathelicidin-type anti-microbial peptide (LL-37) measured in gingival tissue homogenates. Protein concentrations of hBD-2 and LL-37 in gingival tissues were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Gingival tissue samples (n = 14) were homogenized in the presence of proteinase inhibitors. The concentration of each protein, hBD-2 (a) or LL-37 (b), is expressed on the y-axis (ng/mg). The x-axis of both figures indicates the depth of gingival crevice (GC) where the sample tissues were collected (▵, healthy subjects; ▴, periodontally diseased patients). In general, the depth of gingival crevice correlates positively to the degree of bone resorption by the radiographic analysis. Amount of LL-37, but not hBD-2, and depth of gingival crevice showed a positive correlation (P < 0·05).

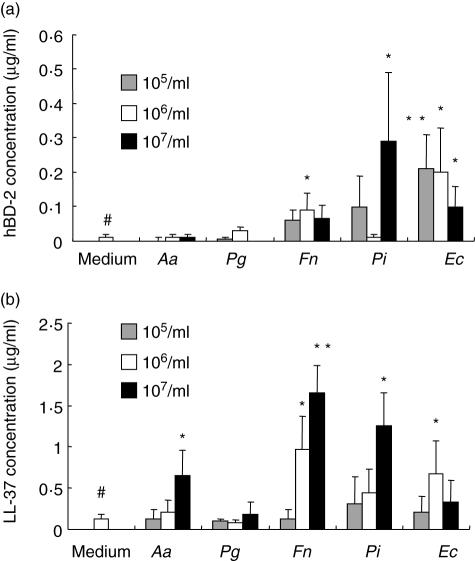

Bacterial stimulation induces production of both hBD-2 and LL-37 by cultured GECs

Human gingival epithelial cell line, OBA-9, was stimulated with five different types of heat-killed bacteria, including A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. gingivalis, F. nucleatum, P. intermedia and E. corrodens. According to RT–PCR examined with total RNA isolated at 24 h after bacterial stimulation, all five bacteria induced the expressions of mRNA for hBD-2 and LL-37 by OBA-9 (data not shown). Specifically, the ELISA demonstrated that F. nucleatum, P. intermedia and E. corrodens enhanced the expression of hBD-2 (Fig. 4a) while, at the same time, A. actinomycetemcomitans, F. nucleatum, P. intermedia and E. corrodens up-regulated the expression of LL-37 (Fig. 4b). This up-regulation is significant, as reported by Ouhara et al. [14]. These investigators found that LL-37 and hBDs possess anti-microbial effects on a variety of periodontal pathogenic bacteria, including A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. gingivalis, P. intermedia and F. nucleatum[14]. Although periodontal disease is defined as polymicrobial infection, A. actinomycetemcomitans and P. gingivalis are accepted as major pathogens for localized aggressive (juvenile) periodontitis and adult periodontal disease, respectively [25,26]. The pathogenic factors, such as cytolethal distending toxin (CDT) and gingipain, produced by A. actinomycetemcomitans and P. gingivalis, respectively, are considered to play aetiological roles in the progression of periodontal diseases [27–29]. Therefore, the up-regulated expression of LL-37 in inflamed gingival tissue may, in fact, facilitate innate defence mechanism against periodontal pathogens.

Fig. 4.

Effects of oral bacterial stimulation on human beta-defensin (hBD)-2 and cathelicidin-type anti-microbial peptide (LL-37) production by gingival epithelial line. Immortalized gingival epithelial cell line, OBA-9, was stimulated with five different types of heat-killed oral bacteria (105, 106 and 107/ml) in 96-well plates for 24 h. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for hBD-2 (a) and LL-37 (b) was performed as described in Materials and methods. The histograms show mean ± 2 s.d. of triplicate wells in 96-well plates. *, **Significantly higher than medium control alone without bacteria (the further left bar with #) by Student's t-test (P < 0·05, P < 0·02), respectively.

Finally, P. gingivalis neither induced a detectable level of hBD-2 nor LL-37 expression by OBA-9 (Fig. 4). In an additional study of the primary culture of GECs, it was found that the bacterial battery identical to that described above also resulted in identical effects, thus demonstrating the similarity of expression patterns for hBD-2 and for LL-37 in response to stimulation with periodontal disease-associated bacteria (data not shown).

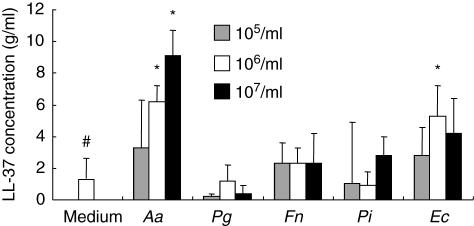

Bacterial stimulation induces production of LL-37, but not hBD-2, from peripheral blood neutrophils

Human peripheral blood neutrophils were stimulated in vitro with the same battery of bacteria as described above (Fig. 5). None of the bacterial stimuli induced detectable hBD-2 production by neutrophils during the different time periods examined [6, 12, 24 and 48 h (data not shown)]. LL-37 expression from neutrophils were induced by stimulation with A. actinomycetemcomitans and E. corrodens, but not with P. gingivalis, F. nucleatum or P. intermedia. The LL-37 production by neutrophils in response to the bacterial stimulation reached maximum at 24 h (24-h stimulation is shown in Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Effects of bacterial stimulation on cathelicidin-type anti-microbial peptide (LL-37) production by peripheral blood neutrophils. Freshly isolated human peripheral blood neutrophils were stimulated with five types of heat-killed oral bacteria (105, 106 and 107/ml) in 24-well plates for 24 h (106 neutrophils/well). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for LL-37 was performed with the culture supernatant as described in Materials and methods in triplicate. The histograms show mean ± 2 s.d. of triplicate data set in 96-well plates. *Significantly higher than medium control alone without bacteria (the further left bar with #) by Student's t-test (P < 0·05).

Discussion

All lines of evidence imply that complex multiple factors are involved in oral host–microbial interaction. Added to this is the fact that not only hBDs and LL-37, but also many other anti-microbial peptides, such as agglutinin, lactoferrin, cystatins and lysozyme, are present in saliva [30]. Thus, the findings in this study, that LL-37 displays distinct expression patterns from those of hBDs in the inflamed gingival tissue, provide relevant data with which to gain insight into innate immune responses in the context of periodontal disease. The present study also demonstrates that the production of LL-37, either by neutrophils or by the epithelium, is up-regulated in the inflamed gingival tissues compared to healthy gingival tissues. However, neutrophils in the gingival tissue did not seem to express either hBD-2 or hBD-3. Specifically, and in view of the multiple factors controlling oral host–pathogen activities, the finding that LL-37 expression is proportional to the severity of periodontal disease may supplement the diagnosis of periodontal disease and lead possibly to new therapeutic approaches to augment the host innate immune defence forces by oral application of synthetic LL-37 peptides.

In the course of the above studies, an interesting anomaly was discovered; namely, that while A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. intermedia, F. nucleatum and E. corrodens induced hBD-2 and LL-37 production by GECs or neutrophils (Figs 4 and 5), P. gingivalis did not induce production of either hBD-2 or LL-37 by OBA-9 or by neutrophils. Krisanaprakornkit et al. [31] reported that F. nucleatum, but not P. gingivalis, is able to induce hBD-2 mRNA expression in primary cultures of GECs. The authors suggested that the lack of ability of P. gingivalis to induce hBD-2 production from GECs may be related to the pathogenesis of P. gingivalis in periodontal disease. The present study also shows that P. gingivalis does not induce protein expression of either hBD-2 or LL-37, which indicates that the pathogenic role of P. gingivalis may be due to the inhibition of hBD and LL-37 production from GECs and neutrophils.

We have found recently that α5β1 integrin expressed on the GECs are involved in the hBD-2 and LL-37 expression by A. actinomycetemcomitans[32]. In particular, outer membrane protein 100 kDa (Omp100) expressed in A. actinomycetemcomitans plays a key role on the hBD-2 and LL-37 expression by GECs. Omp100 binding to cellular fibronectin appears to induce the activation of α5β1 integrin, which gives rise to an intracellular signalling via MAP kinase pathway. Interestingly, neutralizing antibodies to tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α or interleukin (IL)-8 partially inhibited hBD-2 production by GEC in response to Omp100 stimulation, indicating that hBD-2 expression is elicited by a direct response to Omp100 as well as by secondary stimulation with autocrine inflammatory cytokines [32]. A. actinomycetemcomitans Omp100 and its homologous proteins in other bacteria are relatively conserved [33]. Therefore, it is conceivable that periodontal pathogen-mediated production of hBD-2 and LL-37 from GEC and neutrophils may involve similar activation mechanisms to A. actinomycetemcomitans.

In this study, expression of mRNA for hBD-2 and hBD-3 was detected with less frequency in inflamed gingival tissues than in healthy tissues (not shown). Contrary to this result, however, protein concentrations of hBD-2 were slightly higher in inflamed gingival tissues than in healthy tissues (Fig. 3 and Table 1). Because expressions of LL-37 mRNA were observed more in inflamed gingival tissues than in healthy tissues, RNA degradation may not be the cause of reduced expression of mRNA for hBD-2 and for hBD-3 in the inflamed gingival tissues. Other explanations of this phenomenon have been reported. For instance, Dale et al. reported that bacterial stimulation can induce expression of hBD-2 peptide in cultured GECs, as determined by immunofluorescent staining [17]. On the other hand, Bissell et al. showed that the mRNA expressions of hBD-2 and hBD-3 were higher in healthy gingival tissues than periodontally diseased tissues [34]. To some extent, therefore, both studies support the controversial results found in this study as we found that expression patterns of hBD-2 mRNA do not correlate to the hBD-2 protein concentration in the gingival tissues with different degrees of inflammatory conditions.

These lines of evidence indicate that complex, unknown mechanisms may underlie the processes of hBD expression in the gingival tissue that may, in turn, regulate the translation of hBD proteins from their mRNA. One such mechanism is that of ‘post-translational modification’. For example, IL-1β mRNA and pro-IL-1β protein are induced in epithelial cells in response to inflammatory stimulation. However, the functional IL-1β protein is not produced by the epithelial cells because of the lack of IL-1 convertase enzyme (ICE) in the epithelium [35]. The proform of LL-37, an 18-kDa protein designated as hCAP-18, also requires a post-translational proteolytic activity in order to stimulate the release of LL-37, which contains an antibiotic domain [36]. These facts therefore support the following hypothesis: that the measurement of concentrations of LL-37 and hBDs, rather than the detection of their mRNA expression levels, would provide the most plausible information as to the expression profile of functional LL-37 and hBDs, which agrees with the findings established in this study, that is only the beginning of future investigations into the complexities underlying these peptide antibiotics expression mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs Murakami and Kusumoto for OBA-9 cells. This work was supported by grants DE-03420 and DE-14551 from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research.

References

- 1.Bals R. Epithelial anti-microbial peptides in host defence against infection. Respir Res. 2000;1:141–50. doi: 10.1186/rr25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ganz T, Lehrer RI. Defensins. Pharmacol Ther. 1995;66:191–205. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(94)00076-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diamond G, Kaiser V, Rhodes J, Russell JP, Bevins CL. Transcriptional regulation of beta-defensin gene expression in tracheal epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 2000;68:113–19. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.1.113-119.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harder J, Bartels J, Christophers E, Schroder JM. A peptide antibiotic from human skin. Nature. 1997;387:861. doi: 10.1038/43088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valore EV, Park CH, Quayle AJ, Wiles KR, McCray PB, Ganz T., Jr Human beta-defensin-1: an anti-microbial peptide of urogenital tissues. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1633–42. doi: 10.1172/JCI1861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cowland JB, Johnsen AH, Borregaard N. hCAP-18, a cathelin/pro-bactenecin-like protein of human neutrophil specific granules. FEBS Lett. 1995;368:173–6. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00634-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frohm M, Agerberth B, Ahangari G, et al. The expression of the gene coding for the antibacterial peptide LL-37 is induced in human keratinocytes during inflammatory disorders. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:15258–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.24.15258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hase K, Eckmann L, Leopard JD, Varki N, Kagnoff MF. Cell differentiation is a key determinant of cathelicidin LL-37/human cationic anti-microbial protein 18 expression by human colon epithelium. Infect Immun. 2002;70:953–63. doi: 10.1128/iai.70.2.953-963.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bals R, Wang X, Zasloff M, Wilson JM. The peptide antibiotic LL-37/hCAP-18 is expressed in epithelia of the human lung where it has broad anti-microbial activity at the airway surface. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9541–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abiko Y, Jinbu Y, Noguchi T, Nishimura M, Kusano K, Amaratunga P, Shibata T, Kaku T. Upregulation of human beta-defensin 2 peptide expression in oral lichen planus, leukoplakia and candidiasis. an immunohistochemical study. Pathol Res Pract. 2002;198:537–42. doi: 10.1078/0344-0338-00298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu L, Wang L, Jia HP, et al. Structure and mapping of the human beta-defensin HBD-2 gene and its expression at sites of inflammation. Gene. 1998;222:237–44. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00480-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mathews M, Jia HP, Guthmiller JM, et al. Production of beta-defensin anti-microbial peptides by the oral mucosa and salivary glands. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2740–5. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.6.2740-2745.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao C, Wang I, Lehrer RI. Widespread expression of beta-defensin hBD-1 in human secretory glands and epithelial cells. FEBS Lett. 1996;396:319–22. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)01123-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ouhara K, Komatsuzawa H, Yamada S, et al. Susceptibilities of periodontopathogenic and cariogenic bacteria to antibacterial peptides, {beta}-defensins and LL37, produced by human epithelial cells. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;55:888–96. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guthmiller JM, Vargas KG, Srikantha R, et al. Susceptibilities of oral bacteria and yeast to mammalian cathelicidins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:3216–19. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.11.3216-3219.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Putsep K, Carlsson G, Boman HG, Andersson M. Deficiency of antibacterial peptides in patients with morbus Kostmann: an observation study. Lancet. 2002;360:1144–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11201-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dale BA, Kimball JR, Krisanaprakornkit S, et al. Localized anti-microbial peptide expression in human gingiva. J Periodont Res. 2001;36:285–94. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0765.2001.360503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dale BA. Periodontal epithelium: a newly recognized role in health and disease. Periodontology. 2000 2002;30:70–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0757.2002.03007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu Q, Jin L, Darveau RP, Samaranayake LP. Expression of human beta-defensins-1 and -2 peptides in unresolved chronic periodontitis. J Periodont Res. 2004;39:221–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2004.00727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krisanaprakornkit S, Weinberg A, Perez CN, Dale BA. Expression of the peptide antibiotic human beta-defensin 1 in cultured gingival epithelial cells and gingival tissue. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4222–8. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.9.4222-4228.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weinberg A, Krisanaprakornkit S, Dale BA. Epithelial anti-microbial peptides: review and significance for oral applications. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1998;9:399–414. doi: 10.1177/10454411980090040201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Midorikawa K, Ouhara K, Komatsuzawa H, et al. Staphylococcus aureus susceptibility to innate anti-microbial peptides, beta-defensins and CAP18, expressed by human keratinocytes. Infect Immun. 2003;71:3730–9. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.7.3730-3739.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kusumoto Y, Hirano H, Saitoh K, et al. Human gingival epithelial cells produce chemotactic factors interleukin-8 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 after stimulation with Porphyromonas gingivalis via Toll-like receptor 2. J Periodontol. 2004;75:370–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.2004.75.3.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wheeler TT, McArthur WP, Magnusson I, et al. Modeling the relationship between clinical, microbiologic, and immunologic parameters and alveolar bone levels in an elderly population. J Periodontol. 1994;65:68–78. doi: 10.1902/jop.1994.65.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zambon JJ. Actinobaccilus actinomycetemcomitans in human periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 1985;12:1–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1985.tb01348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Socransky SS, Haffajee AD, Ximenez-Fyvie LA, Feres M, Mager D. Ecological consideration in the treatment of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and Porphyromonas gingivalis periodontal infections. Periodontol 2000. 1999;20:341–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1999.tb00165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsai CC, Taichman NS. Dynamics of infection by leukotoxic strains of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in juvenile periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 1986;13:330–1. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1986.tb02231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sugai M, Kawamoto T, Peres SY, et al. The cell cycle-specific growth-inhibitory factor produced by Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans is a cytolethal distending toxin. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5008–19. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.10.5008-5019.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Potempa J, Travis J. Porphyromonas gingivalis proteinases in periodontitis, a review. Acta Biochim Pol. 1996;43:455–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Nieuw Amerongen A, Bolscher JG, Veerman EC. Salivary proteins: protective and diagnostic value in cariology? Caries Res. 2004;38:247–53. doi: 10.1159/000077762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krisanaprakornkit S, Kimball JR, Weinberg A, Darveau RP, Bainbridge BW, Dale BA. Inducible expression of human beta-defensin 2 by Fusobacterium nucleatum in oral epithelial cells: multiple signaling pathways and role of commensal bacteria in innate immunity and the epithelial barrier. Infect Immun. 2000;68:2907–15. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.5.2907-2915.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ouhara K, Komatsuzawa H, Shiba H, et al. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans Omp100 triggers innate immunity, β-defensin and CAP18 (LL37) production, through the fibronectin-integrin pathway in human gingival epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 2006;74:5211–20. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00056-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Komatsuzawa H, Asakawa R, Kawai T, et al. Identification of six major outer membrane proteins from Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Gene. 2002;288:195–201. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)00500-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bissell J, Joly S, Johnson GK, et al. Expression of beta-defensins in gingival health and in periodontal disease. J Oral Pathol Med. 2004;33:278–85. doi: 10.1111/j.0904-2512.2004.00143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mizutani H, Black R, Kupper TS. Human keratinocytes produce but do not process pro-interleukin-1 (IL-1) beta. Different strategies of IL-1 production and processing in monocytes and keratinocytes. J Clin Invest. 1991;87:1066–71. doi: 10.1172/JCI115067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sorensen OE, Follin P, Johnsen AH, et al. Human cathelicidin, hCAP-18, is processed to the anti-microbial peptide LL-37 by extracellular cleavage with proteinase 3. Blood. 2001;97:3951–9. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.12.3951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]