Remaining vigilant for interactions between medications is a formidable challenge for several reasons. The science of drug interactions is dauntingly complex and constantly evolving, the patient's medication list is often a moving target with prescription and nonprescription elements, and dozens of new drugs arrive at our pharmacies each year, often with incompletely characterized drug interaction profiles.

Many clinicians count on office-or pharmacy-based computer software programs to help avert harmful drug interactions. Although these programs have unquestionable advantages over the human brain, they also have important limitations. They identify drug interactions with variable accuracy, rank their severity inconsistently and lack the sophistication to weed out innumerable trivial interactions.1,2 This last point is especially important, because it results in a surfeit of false alarms that can annoy and inure the computer operator, sometimes prompting a reflexive override of more meaningful alerts. Finally, and to the collective shame of the purveyors of drug interaction software, most dispensary computer systems operate in isolation. In an age of electronic immediacy exemplified by instant messaging and online gaming, our pharmacies rely on drug interaction programs that are oblivious to prescriptions dispensed on the other side of town.

Part of the problem relates to the science of drug interactions. Most of what we know about drug interactions derives from case reports and experiments involving healthy volunteers. These sources are often highly instructive, but case reports are case reports for a reason, and healthy volunteers are, by definition, free of the modifying effects of other drugs and diseases. There is a lamentable paucity of thoughtful, controlled experiments exploring the consequences of drug interactions in real-world patients, primarily because such studies require large databases that permit the linkage of outpatient prescription records with laboratory data or clinical outcomes.

In this issue of CMAJ, Delaney and colleagues report the findings of a population-based, retrospective case–control study in which they explored the association between gastrointestinal bleeding and antithrombotic drug use using records in the United Kingdom General Practice Research Database, a database of a network of more than 400 general practices in the United Kingdom. The authors found that antiplatelet agents, taken in combination or with warfarin, are associated with an increased risk of gastrointestinal hemorrhage compared with the individual drugs alone.3 At first blush, the findings might seem so clinically intuitive that they hardly merit study. However, this is not the case. This research accomplishes 3 important things. First, it provides an estimate of the excess risk associated with combinations of antiplatelet agents and warfarin. Second, it reminds clinicians that, if we opt to prescribe these drugs in combination, especially for an extended period, we had better have a good reason to do so, and inform the patient appropriately. Finally, because Delaney and colleagues answer a clinically relevant question using a thoughtful and sophisticated approach, their study contributes to our understanding of these drug interactions in ways uncontrolled observations cannot.

Ask any physician or pharmacist to name one drug that is highly prone to dangerous drug interactions, and many will immediately cite warfarin. This concern is justified. Literally hundreds of drugs can increase the risk of hemorrhage in patients receiving warfarin, including some nonprescription drugs widely perceived as innocuous.4,5 These interactions are largely avoidable, yet they can precipitate bleeding that is often unheralded and sometimes life-threatening. To complicate matters, patients receiving warfarin tend to be older, take several other medications concomitantly and have comorbidities that increase their risk for hemorrhage.

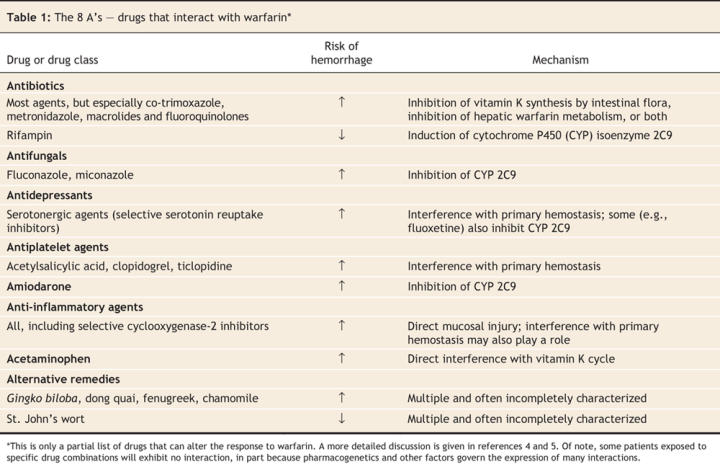

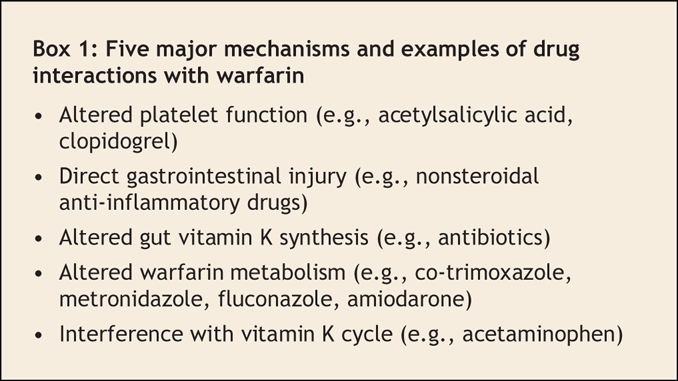

Fortunately, most clinically relevant interactions with warfarin involve drugs from a small number of classes (Table 1) and occur by only a handful of mechanisms (Box 1):

Table 1

Box 1.

• Interference with platelet function: Platelet aggregation is a crucial first step in primary hemostasis. As shown by Delaney and colleagues, drugs that impair platelet function, such as acetylsalicylic acid and clopidogrel, increase the risk of major hemorrhage in patients taking warfarin, and they do so without elevating the international normalized ratio. Converging lines of evidence also suggest that antidepressants, particularly selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, can inhibit platelet aggregation by depleting platelet serotonin levels.6 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are commonly co-prescribed with warfarin and may be an important independent risk factor for major bleeding.

• Injury to gastrointestinal mucosa: This interaction is intuitive yet sometimes overlooked. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs cause dose-and duration-dependent gastrointestinal erosions in a substantial proportion of patients.7 Most of these erosions are asymptomatic, but the risk of hemorrhage is heightened considerably by the concomitant use of warfarin, even in patients whose international normalized ratio lies within the desired range.

• Reduced synthesis of vitamin K by intestinal flora: The hypoprothrombinemic response to warfarin is influenced by vitamin K status, which is partly dependent on the synthesis of vitamin K2 (menaquinone) by intestinal microflora. Many antibiotics alter the balance of gut flora, thereby enhancing the effect of warfarin.8 Although interactions of this type are predictable, their expression is highly variable. Holbrook and colleagues have sensibly urged caution when adding any antibiotic to a warfarin-containing regimen,4 but some antibiotics also inhibit the hepatic metabolism of warfarin (outlined in the next paragraph) and therefore merit special consideration. These antibiotics include co-trimoxazole and metronidazole and, to a lesser extent, the macrolides and fluoroquinolones.

• Interference with warfarin metabolism: Commercially available warfarin exists as a racemic mixture of 2 isomers: S-warfarin and R-warfarin. The former is approximately 5–6 times more biologically active than the latter and is metabolized by the cytochrome P450 (CYP) isoenzyme 2C9.4,9 Consequently, drugs that inhibit this enzyme (e.g., amiodarone, co-trimoxazole, metronidazole and fluvoxamine) potentiate the effect of warfarin and necessitate a lower warfarin dose for most patients. The few drugs that induce CYP 2C9 activity (e.g., rifampin) will do the converse. Interestingly, R-warfarin is metabolized by different hepatic enzymes (CYP 3A4, CYP 1A2 and CYP 2C19). Because R-warfarin has less biological activity than S-warfarin, as well as alternate pathways of elimination, drugs that inhibit these enzymes generally have less dramatic effects on anticoagulation control.

• Interruption of the vitamin K cycle: By far the most important drug in this category is acetaminophen. Recent evidence suggests that this interaction is caused by N-acetyl (p)-benzoquinonimine, the highly reactive metabolite of acetaminophen responsible for hepatic injury following acetaminophen overdose. Therapeutic doses of acetaminophen yield some of this metabolite, which inhibits vitamin K-dependent carboxylase, a key enzyme in the vitamin K cycle.10 For reasons that are unclear, some patients but not others experience a rapid and dramatic rise in the international normalized ratio following standard doses of acetaminophen.

In summary, patients taking warfarin are susceptible to numerous drug interactions. Most of these are avoidable, although warfarin–analgesic interactions present clinicians with a therapeutic dilemma. The majority of interactions result in an increased risk of hemorrhage, and most, but not all, of these are accompanied by an elevated international normalized ratio. Fortunately for clinicians, common precipitants of drug interactions with warfarin fall into a few familiar drug classes, and their effects manifest via a limited number of mechanisms, many of which are intuitive. The risk of harm due to drug interactions can be lessened by awareness of these principles, thoughtful prescribing habits and judicious monitoring when new drugs are added to regimens containing warfarin.

@ See related articles pages 347 and 357

Acknowledgments

I thank Drs. Anne Holbrook and William Bartle for their comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Competing interests: None declared.

Correspondence to: Dr. David N. Juurlink, Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, G Wing 106, 2075 Bayview Ave., Toronto ON M4N 3M5; dnj@ices.on.ca

REFERENCES

- 1.Malone DC, Abarca J, Hansten PD, et al. Identification of serious drug–drug interactions: results of the partnership to prevent drug–drug interactions. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2004;44:142-51. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Hazlet TK, Lee TA, Hansten PD, Horn JR. Performance of community pharmacy drug interaction software. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash) 2001;41:200-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Delaney JA, Opatrny L, Brophy JM, et al. Drug–drug interactions between antithrombotic medications and the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding. CMAJ 2007;177(4):347-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Holbrook AM, Pereira JA, Labiris R, et al. Systematic overview of warfarin and its drug and food interactions. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:1095-106. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Greenblatt DJ, von Moltke LL. Interaction of warfarin with drugs, natural substances, and foods. J Clin Pharmacol 2005;45:127-32. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Maurer-Spurej E, Pittendreigh C, Solomons K. The influence of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on human platelet serotonin. Thromb Haemost 2004;91:119-28. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Fortun PJ, Hawkey CJ. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and the small intestine. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2007;23:134-41. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Conly JM, Stein K, Worobetz L, et al. The contribution of vitamin K2 (menaquinones) produced by the intestinal microflora to human nutritional requirements for vitamin K. Am J Gastroenterol 1994;89:915-23. [PubMed]

- 9.Takahashi H, Echizen H. Pharmacogenetics of warfarin elimination and its clinical implications. Clin Pharmacokinet 2001;40:587-603. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Thijssen HH, Soute BA, Vervoort LM, et al. Paracetamol (acetaminophen) warfarin interaction: NAPQI, the toxic metabolite of paracetamol, is an inhibitor of enzymes in the vitamin K cycle. Thromb Haemost 2004;92:797-802. [DOI] [PubMed]