Abstract

Methylation of specific amino acids in histone tails is responsible for packaging DNA into condensed, repressed chromatin, and into open chromatin that is accessible to the transcription machinery. Monomethylation and trimethylation of histone H4-lysine 20 (H4-K20) control the formation of repressed chromatin. Using antibodies that specifically recognize the three methyl marks of histone H4-K20, we characterized their regulation during the cell cycle and throughout development. We find free mono- and trimethylated histone H4-K20 in unfertilized Drosophila eggs and in S2 tissue culture cells. Soluble mono-. di-, and trimethylated H4-K20 are also found in HeLa cells. These soluble modified histones may represent a pool of free histones that can rapidly be incorporated into chromatin. The three methyl marks are each regulated differentially during development and their detection on western blots does not overlap with their detection on chromosomes. Monomethylated H4-K20 is detected on condensed chromosomes throughout development, while di-, and trimethylated H4-K20 is detected on metaphase chromosomes at specific stages. Our results suggest that the detection of methylated H4-K20 on chromosomes may reveal chromatin packaging rather than the distribution of the methyl marks.

Keywords: Histone methylation, chromatin, free histones, cell cycle and mitosis, Drosophila

INTRODUCTION

Histones have long been recognized as forming the core of nucleosomes, the basic unit of chromatin. It is now evident that the modification of histone tails has a major effect on higher order chromatin structure, controlling the activation or silencing of particular genes by rendering chromatin accessible or inaccessible to DNA binding proteins like the transcriptional machinery (Reinberg et al., 2004). One of these modifications, histone methylation, is regulated by histone methyl transferases (HMTs) that can modify either arginine or lysine residues. Under the control of specific HMTs, lysine residues can be mono-, di-, or trimethylated (Peterson and Laniel, 2004).

Histone H4-K20 monomethylation is controlled by the PR-Set7 (or Set8) HMT (Nishioka et al., 2002; Fang et al., 2002; Couture et al., 2005; Xiao et al., 2005), and the Suv4-20 HMT controls the trimethylation of the same lysine (Schotta et al., 2004). Both enzymes are conserved from flies to humans, but in S. pombe mono-, di-, and trimethylation of H4-K20 is controlled by one enzyme, the Set9 HMT. In HeLa cells, the expression of PR-Set7 was found to be cell-cycle regulated with highest levels at G2/M phase and with lower levels in G1 and S phases. Methylation of H4-K20 was also found to peak during mitosis (Rice et al., 2002).

By antibody staining, methylation of H4-K20 in HeLa cells was observed specifically on mitotic chromosomes (Rice et al., 2002). On salivary gland chromosomes all three methyl marks overlap, staining heterochromatin and euchromatin, except for trimethylated H4-K20, that is enriched in the pericentric heterochromatin. On the euchromatic chromosome arms, the three methyl marks are found on condensed regions, a distribution distinct from the staining pattern of H3-K4, and a mark of transcriptionally active genes. Co-staining of the three methyl marks and transcriptionally active RNA polymerase also showed no overlap, indicating that the marks are associated with silent chromatin (Nishioka et al., 2002; Rice et al., 2002; Karachentsev et al., 2005).

Consistent with these staining results above, mutants in PR-Set7 and Suv4-20 were found to suppress position effect variegation, indicating that both genes function in silencing gene expression (Schotta et al., 2004, Karachentsev et al., 2005). Monomethylation is also essential for the normal progression through the cell cycle. Imaginal discs from mutants lacking PR-Set7 have only ~25% as many cells as wild-type discs and the cells are larger (Karachentsev et al., 2005).

The monomethyl mark is stable over several cell generations, because in homozygous PR-Set7 animals the enzyme cannot be detected on western blots from the 1st instar larval stage onward. On the other hand, monomethylated H40-K20 can be detected on salivary glands of early third instar larvae and disappears only in late third instar (Karachentsev et al., 2002).

Histone methylation was originally thought to be a stable modification controlling gene expression, with the marks set at specific stages of development, and inherited from mother to daughter cells. But now lysine demethylases have been identified, suggesting that the histone methylation marks are reversible and that the marks may have a more transient function (Shi et al., 2004; Trojer and Reinberg, 2006).

We chose a developmental approach to determining the regulation and distribution of the three methylated states of the same lysine of histone H4. We investigated if the modifications are stable during development and the cell cycle, if their distribution on chromosomes is linked, and if different cell types show distinct patterns of distribution.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and synchronization

HeLa cells (ATCC) were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen). To arrest cells in G1, cells were treated with 2 mM thymidine (Sigma) for 16 h, released into fresh media for 8 h, and blocked again by addition of 0.4 mM mimosine overnight (Sigma). Cells were released into fresh media and time points were taken every 2.5 h (Rice et al., 2002). At each time point, 105 cells were used for western blot analysis. Drosophila S2 cells (ATCC) were grown in SFM (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum.

Protein analysis

Histones were fractionated from cultured cells as described in Schwartz and Ahmad (2005). Briefly, cells were lysed in buffer containing 0.5% NP-40, 0.4 M NaCl, 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 10 mM Tris HCl pH 8, protease inhibitors. Chromatin was collected by centrifugation at 14,000 g for 10 min at 4C. The supernatant (containing soluble histones) was dialyzed against 10 mM Tris HCl pH 8. Samples were mixed with SDS loading buffer and separated on 14% PAGE.

Cell fractionation

Drosophila S2 cells were pelleted and resuspended in small volume of cold 4C, 10 mM Tris HCl pH 8, 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, and protease inhibitor cocktail. Cells were mechanically lysed with few strokes in Dounce homogenizer. Nuclei were collected by centrifugation at 14,000 g for 10 min at 4C. The supernatant and pellet were separately collected. Samples were mixed with SDS loading buffer and separated on 8% PAAG. Western blot was probed with 1:1000 dilution of anti-DrosPRSet7 antibodies published previously (Karachentsev et al., 2005).

Western blots

Western blot analysis was performed as described (Whalen and Steward, 1993). Fly tissues were homogenized in 2–3 volumes of standard SDS PAGE protein loading buffer. Antibodies were used in the following dilutions: anti-H4-K20 mono-, di-, and trimethyl rabbit polyclonal antibody (Upstate, Inc.) 1:1000. Native nucleosomes were purified from HeLa cells as previously described (Orphanides et al., 1998). Unfertilized eggs were collected every 2 hours from wild type virgins crossed with sterile bamΔ86 males.

Antibody staining of tissues

Antibody staining of Drosophila ovaries and embryos was performed as described in Whalen and Steward (1993). Mitotic brain chromosomes of third instar larvae were prepared as described by Ashburner (1989). Tissues were stained with the following antibodies: 1:200 dilution of anti-H4-K20 mono- di-, and trimethyl rabbit polyclonal (Upstate); anti-H3-S28P polyclonal antibody (Upstate) 1:100; anti-H3-S10P mouse monoclonal antibody (Upstate) 1:100; mouse monoclonal anti-Pol II antibody (Covance H5) 1:100; anti-tubulin FITC-conjugated antibody (Molecular Probes). Staining was visualized using a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope and an AxioCam HRm digital camera. Images were analyzed with the Image Pro Plus software.

RESULTS

Methylation of histone H4-K20 occurs cell cycle-specifically; in HeLa cells, PR-Set7 levels and methylated H4-K20 change during the cell cycle and the detection of methylated histone H4-K20 on chromosomes is cell cycle-specific (Rice et al., 2002). These observations raise two basic questions: are all three methyl-forms of H4-K20 coordinately regulated during the cell cycle and during development, and what happens to the methyl marks in interphase chromatin?

The three methyl marks of histone H4-K20 are developmentally regulated

To determine possible diverse functions of the three methyl marks of H4-K20 we investigated their regulation during development. On salivary gland chromosomes the distribution of each, the mono-, di-, and trimethylated forms of histone H4-K20, are almost identical (Karachentsev et al., 2005). But we find that the appearance and levels of the methylated histones are developmentally controlled and are variable.

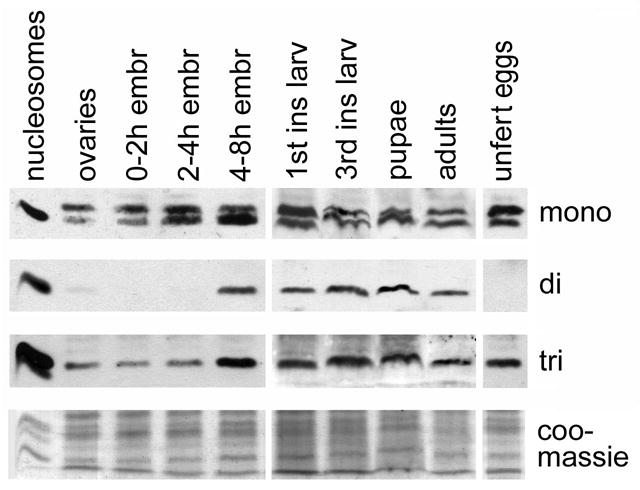

On developmental western blots (Fig. 1), both monomethylated and trimethylated histone H4-K20 are present in adults, in ovaries, early embryos, and throughout larval and pupal stages. The dimethylated form of histone H4-K20 is not detected in ovaries or in early embryos, and first becomes apparent only between 4 and 8 hours of embryogenesis, then remains present throughout development.

Figure 1. Developmental profile of the three methyl marks of histone H4-K20.

Western blots probed with anti-mono, anti-di, and anti-trimethylated histone H4-K20. The first lane contains purified nucleosomes isolated from HeLa cells. The upper band present on the “mono” blot is a cytoplasmic uncharacterized protein. Lowest panel, coomassie stain, shows the amount of proteins loaded.

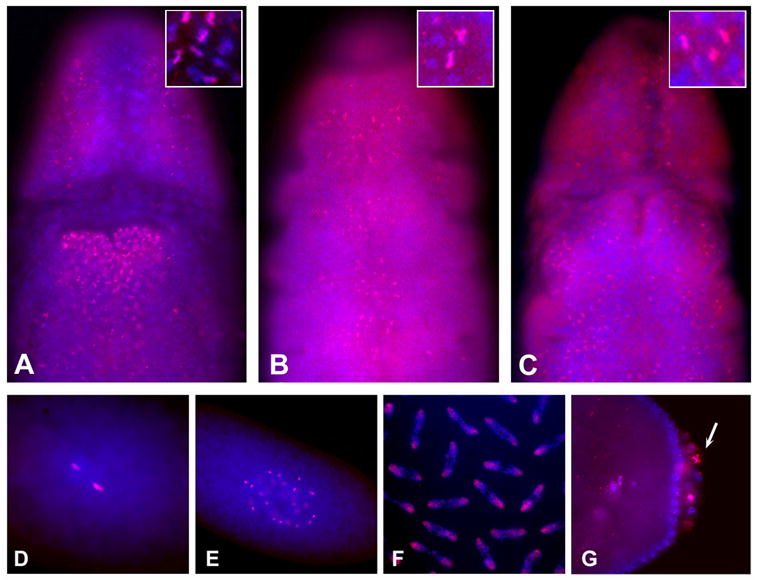

We also performed immunofluorescence studies to determine when the three methyl marks were demonstrable on chromosomes. While the staining patterns of mono- and trimethylation were apparent at different stages of development (see below), dimethylation was detected clearly only at the extended germ-band stage about 7 hours into development, when mono-, and trimethylation are also seen (Fig. 2A–C). Di, and trimethylated H4-K20 are generally detected on few nuclei, specifically in metaphase, and are not detected on interphase nuclei (Fig. 2A–C, insets). Monomethylated H4-K20 is detected on a larger number of chromosomes and, as in ovaries and younger embryos, is present on condensed chromosomes. As expected, the dimethylation staining was not seen during oogenesis or in early embryos, and neither could we detect it on larval tissues, indicating that the highest levels of dimethylated H4-K20 are observed in mid-gastrula stage embryos. Lower levels present at other stages of development may have been missed because of the quality of the anti-dimethylated H4-K20 antibody.

Figure 2. Distribution of the H4-K20 methyl marks during embryogenesis.

A – C. Gastrulation stage embryos stained with anti-monomethylated histone H4-K20 (A), anti-dimethylated histone H4-K20 (B). anti-trimethylated histone H4-K20 (C). The inset in each panel show a higher magnification, note that the majority of nuclei in all animals do not stain. D–F. Cleavage and blastoderm stage embryos stained with anti-monomethylated histone H4-K20. Embryo at first mitosis (D), cleavage stage embryo (E), cleavage stage embryo in mitosis (F), syncytial stage blastoderm stage embryo (G). Anti-methylated H4-K20 antibodies are shown in red and DNA dye, Hoechst, in blue.

H4-K20 methylation during the cell cycle

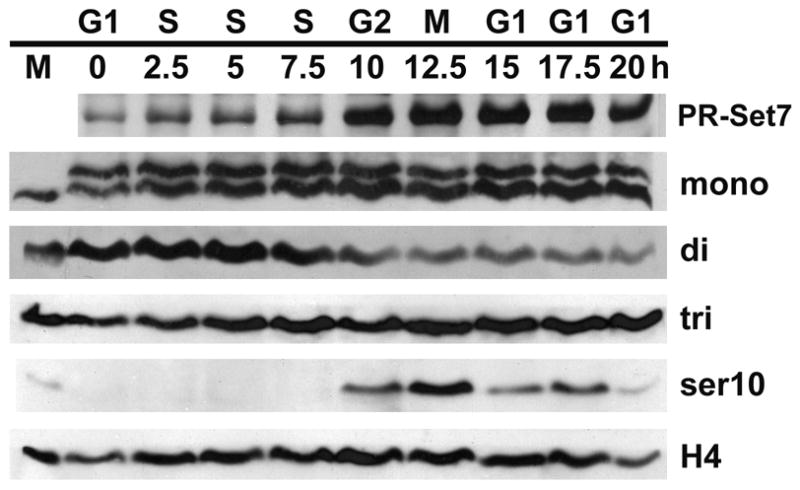

Because of the cell cycle-specific detection of the H4-K20 methyl marks on HeLa cell chromosomes (Rice et al., 2002), we decided to determine the distribution of the mono-, di-, and trimethyl H4-K20 marks throughout the cell cycle by western blot analysis. Hela cells were arrested in G1 by thymidine followed by mimosine treatment. After release of the cells into fresh medium, aliquots were collected every 2.5 hours (Rice et al., 2002). Total cell extracts were fractionated on SDS/PAGE and the western blot was probed with different antibodies (Fig. 3). The cell cycle-specific detection of H3-Ser10 phosphorylation shows that the cells were synchronized successfully.

Figure 3. Cell cycle profile of H4-K20 methylation.

Western blots of synchronized HeLa cells probed with anti-PR-Set7, anti-mono-, anti-di-, anti-trimethylated histone H4-K20 and anti-phosphorylated H3-S10. The first lane contains nuclei from nonsynchronized HeLa cells. Lowest panel, anti-histone H4, shows the amount of proteins loaded.

As previously observed, the levels of PR-Set7 are lowest in G1/S and culminate at G2/M (Rice et al., 2002). Mono- and trimethylation of histone H4-K20 levels appear relatively stable during the cell cycle, while dimethylation of H4-K20 follows a cyclical pattern with maximum levels in S phase.

The monomethyl and trimethyl marks are both cell cycle-specifically detected on chromosomes

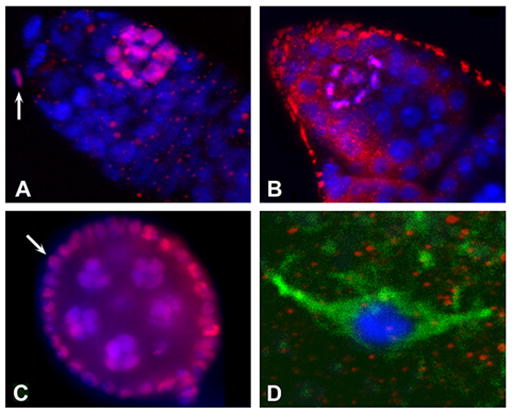

Our western blots show that monomethylated histone H4-K20 is detected throughout development and throughout the cell cycle. Nevertheless, it is only detectable by antibody staining on chromosomes at specific stages. Figure 4A shows a germarium containing the early stages of oogenesis when groups of cells (cystocytes) undergo synchronous mitoses (for a review of oogenesis see Spradling, 1993). Monomethylation is seen in clusters of cystocytes. Screening of more than 100 germaria shows that detection of the monomethyl mark is not developmentally specific but cell cycle-specific. Staining of monomethylated H4-K20 is observed in ~30% of the germaria and sometimes in more than one cyst.

Figure 4. Distribution of the H4-K20 methylmarks during oogenesis.

A. Germarium stained with anti-monomethylated H4-K20. B. Germarium stained with anti-trimethylated H4-K20. C. Stage 5–6 egg chamber stained with anti-monomethylated H4-K20. D. Stage 14 oocyte at metaphase of meiosis 1 stained with anti-monomethylated H4-K20. Anti-methylated H4-K20 is shown in red, DNA dye in blue, and anti-αtubulin in green.

Trimethylated histone H4-K20 (Fig. 4B) is observed only in early germaria. This staining is always associated with metaphase chromosomes and is only observed in one cyst in ~5% of ovarioles. It overlaps with the detection of phosphorylated histone H3-S10P (H3P) by a monoclonal antibody, specific for metaphase chromosomes (data not shown). This is strong indication that in oogenesis the trimethyl mark is specific for metaphase chromosomes.

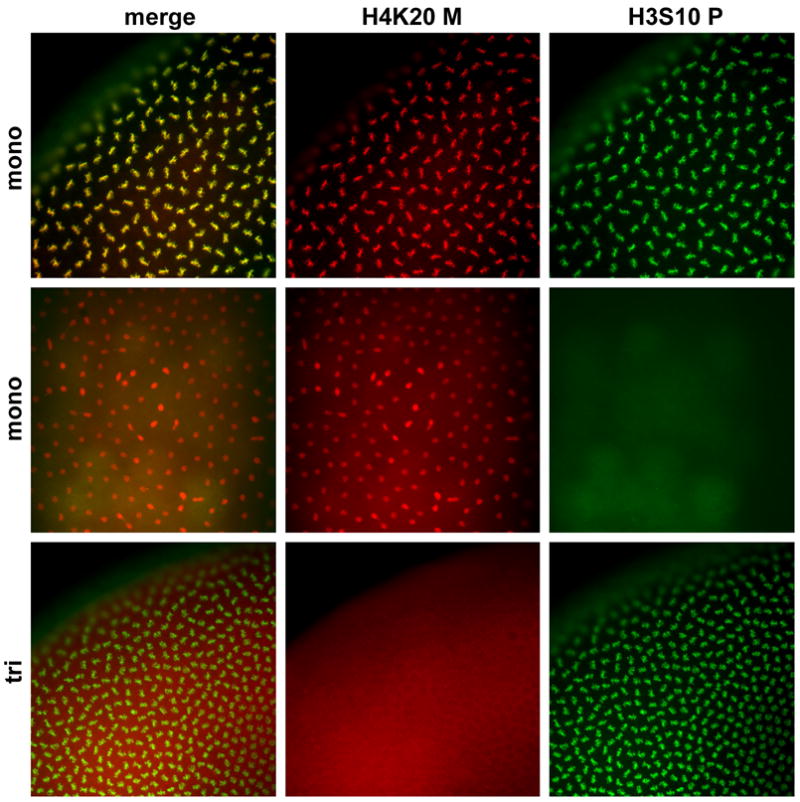

Monomethylation of histone H4-K20 is observed throughout oogenesis in dividing cells, but it is not detected on pachytene chromosomes of stage 14 oocyte (Fig. 4C,D). Immediately upon fertilization, the monomethyl mark is clearly visible (Fig. 2D). The cleavage stage cell cycle only consists of S and M phases and lasts 8 to 9 minutes (Foe et al., 1993). During these early stages of embryonic development, the monomethylated H4-K20 is detected continuously on all chromosomes (Fig. 2E,F and 5), unlike H3P staining that is detected specifically on metaphase chromosomes (Fig. 5). At the blastoderm stage, when the cell cycle incorporates G phases and lasts 2 to 3 times longer, anti-monomethylated H4-K20 staining is again associated specifically with condensed chromosomes, and interphase nuclei show no or only very low levels of staining. This cell cycle specificity of the monomethyl mark is also observed in pole cells (Fig. 2G). Some pole cells stain strongly and others not at all, presumably because their divisions are asynchronous.

Figure 5. The mono-methyl mark is present throughout the cell cycle in early embryos, while the trimethyl mark is not detected.

Cleavage stage embryos stained with anti-monomethylated and anti-trimethylated H4-K20 antibodies (red) and anti-H3P antibodies (green).

Trimethylated H4-K20 is undetectable at any stage of early development until mid-gastrulation. Blastoderm stage metaphase chromosomes positive for H3P staining do not stain with anti-trimethylated H4-K20 (Fig. 5). This result is surprising since western blots of chromatin isolated from 0–3h embryos show that trimethylated H4-K20 is clearly associated with chromatin in early, 0–3h embryos (Fig. 1S).

Free methylated histone H4-K20

Histone methyltransferases are thought to function when bound to DNA and to methylate histones when they become incorporated onto the nucleosomes (Zhang and Reinberg 2001). But on our developmental western blots we detected mono- and trimethylated histones H4-K20 present in unfertilized eggs, while no dimethylated H4-K20 was apparent (Fig. 1). At this stage the oocyte is in pachytene of the first meiotic division. Each oocyte contains only 4 copies of each chromosome and the chromosomes are condensed. Thus, the bulk of the mono- and tri-methylated forms of histone H4-K20 we observe on the western blots are not associated with DNA.

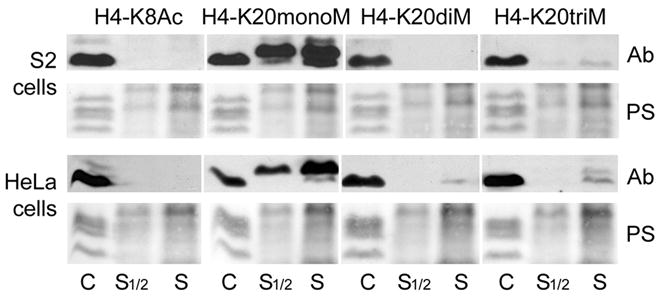

We wondered if methylated, soluble histones are present in mammalian and fly tissue culture cells. S2 Drosophila and HeLa cells were fractionated into nucleosomes and free histones using a 0.4 M salt buffer, followed by centrifugation (see Material and Methods; Schwartz and Ahmad, 2005). The pellet containing the chromatin fraction and the supernatant containing the free histones were separated by SDS/PAGE (Fig. 6). On western blots most of the methylated H4-K20 is found in the chromatin fraction, as expected. But in both the S2 and HeLa extracts, substantial amounts of monomethylated H4-K20 are present in the free fraction. Traces of trimethylated H4-K20 are also detected in the soluble histone fractions from S2 cells, while low levels of di-, and trimethylated H4-K20 are observed in HeLa cells. As a control we found that, as expected, H4-K8 acetylation is only observed on chromatin but not in the soluble fraction (Sobel et al., 1995).

Figure 6. Histone H4-K20 methylated variants are present in soluble fractions.

Western blots of soluble and chromatin bound fractions from HeLa and Drosophila S2 cells probed with anti-mono-, anti-di-, anti-trimethylated histone H4-K20 and anti-acetylated H4-K8. Lower panels, ponceau staining, show the amount of proteins loaded.

DISCUSSION

Stability of the three H4-K20 methyl marks

The histone code theory posits that epigenetic marks are stable, inherited from one cell generation to the next, and that they affect gene expression. Bulk chromatin is assembled during S phase and it is assumed that most HMTs function at that time to modify lysines of histones on specific nucleosomes (Jenuwein and Allis, 2001).

In agreement with the histone code hypothesis, we found previously that the monomethyl mark of histone H4-K20 is stable over several days. Animals lacking the PR-Set7 HMT die at the larval-to-pupal transition, and monomethylated histone H4-K20 is still present in third instar larvae until about 1 day before the animals die (Karachentsev et al. 2005). We now find that the mono- and trimethylation marks of histone H4-K20 are present throughout development and are also relatively stable throughout the cell cycle. It is unlikely that demethylases exist to remove these methyl marks before they are reset in each new cell generation, but low levels of exchange of the methylated histones may occur.

The dimethyl mark behaves differently. It is not present during oogenesis and only appears in the gastrula stage ~8 hours into development. In HeLa cells, the levels of dimethylated histone H4-K20 peak during S phase and are reduced during mitosis, suggesting that a demethylase regulating the levels of the H4-K20 dimethyl mark could exist.

Pre-deposition mono- and trimethylated H4-K20

It has been thought that histones are methylated when they are assembled into nucleosomes. Our finding of free mono- and trimethylated histone H4-K20 in the ooplasm indicates that the Drosophila mono-HMT Pr-Set7 and tri-HMT Suv4-20 can modify free histones. This modification probably occurs when the histones are first synthesized and deposited in the oocyte. The Drosophila egg contains high levels of maternally deposited histones incorporated into chromatin during the rapid cell cycles in the early embryo. It is therefore not surprising that some of these pre-deposition histones are modified (Walker and Bownes 1998).

Even though the methyl marks are relatively stable, we unexpectedly find consistent levels of free, pre-deposition monomethylated histones in S2 cells. Similarly, in HeLa cells free mono- and trimethylated H4-K20 are readily detected, and lower levels of free dimethylated histones are apparent. The presence of pre-deposition histones in Drosophila and mammalian tissue culture cells suggests that the modification of free histones by HMTs is occurring in most if not all tissues, and that it is conserved from flies to vertebrates. Soluble, methylated histones in S2 and HeLa cells are likely to represent a pool of free histones that can rapidly be incorporated into chromatin. Sims et al. (2006) found that the three H4-K20 methyl marks show distinct distributions in HeLa cell nuclei. It is possible that the pools of pre-deposition modified mono-, di-, and trimethylated histones are sequestered to specific areas of the nucleus.

Stability of the three H4-K20 methyl marks and their cell-cycle-specific detection on chromosomes

On western blots of HeLa cells, all three methyl marks are present throughout the cell cycle. The preponderance of the three modified histones H4-K20 is associated with chromatin in Hela and S2 cells. It therefore is likely that the methylated histones are associated with chromatin throughout the cell cycle.

Monomethylated histone H4-K20 and trimethylated H4-K20 can each be detected by antibody staining at specific and overlapping stages of the cell cycle. The monomethyl mark is present from late G2 throughout mitosis and represents an excellent marker for condensed chromosomes during mitosis at all stages of development. Di- and trimethylated histones H4-K20 are visible on metaphase chromosomes, but only at specific stages of development. Further, on western blots of early embryos trimethylated H4-K20 is found in the chromatin fraction, but the trimethyl mark is not detected on chromosomes by antibody staining.

Together, these western and antibody staining results suggest that when the methyl marks are not detected they are too diluted, or are obscured by additional and reversible modifications of histone H4, or that they are buried by chromatin packaging. It is possible that the distribution of the H4-K20 methyl marks is general and that antibody staining reflects higher order chromatin packaging rather than the distinct localization of each modification.

In early embryos, antibody staining reveals the monomethyl mark throughout the shortened cell cycle, and the trimethyl mark is not detected. This result is consistent with the idea that higher order packaging is different in the nuclei of early embryos than in nuclei during oogenesis or in gastrulating embryos. Similarly, the banding pattern of the three forms of methylated H4-K20 detected on salivary gland chromosomes may reflect the packaging of chromatin rather than the distribution of the marks. Just as specific histone lysine methyl marks show different stabilities (Trojer and Reinberg, 2006), some methyl marks may be associated with specific DNA sequences, while others may be more uniformly distributed.

That the mono- and trimethyl marks are detected on chromosomes at different stages of the cell cycle and development implies that they are not interspersed but are associated with separate domains of chromatin accessible to antibodies at specific stages.

Supplementary Material

Trimethylated histone H4-K20 is associated with chromatin in early embryos. Western blots of soluble and chromatin bound fractions from 0–3 hour old embryos probed with anti-trimethylated histone H4-K20.

Acknowledgments

We thank Danny Reinberg and Kavitha Sarma for anti PR-Set7 antibodies, and Michael Hampsey and Girish Deshpande for critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank Le Nguyen for technical help and fly food. This work was supported by a grant from the NIH and by the Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ashburner M. Drosophila, a laboratory handbook. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Loranger SS, Mizzen C, Ernst SG, Allis CD, Annunziato AT. Histones in transit: cytosolic histone complexes and diacetylation of H4 during nucleosome assembly in human cells. Biochemistry. 1997;36:469–80. doi: 10.1021/bi962069i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couture JF, Collazo E, Brunzelle JS, Trievel RC. Structural and functional analysis of SET8, a histone H4 Lys-20 methyltransferase. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1455–65. doi: 10.1101/gad.1318405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosio C, Fimia GM, Loury R, Kimura M, Okano Y, Zhou H, Sen S, Allis CD, Sassone-Corsi P. Mitotic phosphorylation of histone H3: spatio-temporal regulation by mammalian Aurora kinases. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:874–85. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.3.874-885.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dej KJ, Spradling AC. The endocycle controls nurse cell polytene chromosome structure during Drosophila oogenesis. Development. 1999;126:293–303. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.2.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang J, Feng Q, Ketel CS, Wang H, Cao R, Xia L, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Simon JA, Zhang Y. Purification and functional characterization of SET8, a nucleosomal histone H4-lysine 20-specific methyltransferase. Curr Biol. 2002;9:1086–99. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00924-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foe VE, Odell GM, Edgar BA. Mitosis and morphogenesis in the Drosophila embryo: point and counterpoint. In: Bate M, Arias AM, editors. The development of Drosophila melanogaster. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1993. pp. 149–301. [Google Scholar]

- Jenuwein T, Allis CD. Translating the histone code. Science. 2001;294:2477. doi: 10.1126/science.1063127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karachentsev D, Sarma K, Reinberg D, Steward R. PR-Set7-dependent methylation of histone H4 Lys 20 functions in repression of gene expression and is essential for mitosis. Genes Dev. 2005;19:431–5. doi: 10.1101/gad.1263005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishioka K, Rice JC, Sarma K, Erdjument-Bromage H, Werner J, Wang Y, Chuikov S, Valenzuela P, Tempst P, Steward R, Lis JT, Allis CD, Reinberg D. PR-Set7 is a nucleosome-specific methyltransferase that modifies lysine 20 of histone H4 and is associated with silent chromatin. Mol Cell. 2002;9:1201–13. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00548-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolz JC, Gomez TS, Billadeau DD. The Ezh2 methyltransferase complex: actin up in the cytosol. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:514–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orphanides G, LeRoy G, Chang CH, Luse DS, Reinberg D. FACT, a factor that facilitates transcript elongation through nucleosomes. Cell. 1998;92:105–16. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80903-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson CL, Laniel MA. Histones and histone modifications. Curr Biol. 2004;14:546–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinberg D, Chuikov S, Farnham P, Karachentsev D, Kirmizis A, Kuzmichev A, Margueron R, Nishioka K, Preissner TS, Sarma K, Abate-Shen C, Steward R, Vaquero A. Steps toward understanding the inheritance of repressive methyl-lysine marks in histones. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2004;69:171–82. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2004.69.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice JC, Nishioka K, Sarma K, Steward R, Reinberg D, Allis CD. Mitotic-specific methylation of histone H4 Lys 20 follows increased PR-Set7 expression and its localization to mitotic chromosomes. Genes Dev. 2002;1:2225–30. doi: 10.1101/gad.1014902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schotta G, Lachner M, Sarma K, Ebert A, Sengupta R, Reuter G, Reinberg D, Jenuwein T. A silencing pathway to induce H3-K9 and H4-K20 trimethylation at constitutive heterochromatin. Genes Dev. 2004;1:1251–62. doi: 10.1101/gad.300704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz BE, Ahmad K. Transcriptional activation triggers deposition and removal of the histone variant H3.3. Genes Dev. 2005;19:804–14. doi: 10.1101/gad.1259805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Lan F, Matson C, Mulligan P, Whetstine JR, Cole PA, Casero RA, Shi Y. Histone demethylation mediated by the nuclear amine oxidase homolog LSD1. Cell. 2004;119:941–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel RE, Cook RG, Perry CA, Annunziato AT, Allis CD. Conservation of deposition-related acetylation sites in newly synthesized histones H3 and H4. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:1237–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.4.1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spradling A. In: Developmental genetics of oogenesis. Bate M, Arias AM, editors. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1993. pp. 2–148. [Google Scholar]

- Trojer P, Reinberg D. Histone lysine demethylases and their impact on epigenetics. Cell. 2006;125:213–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukada Y, Fang J, Erdjument-Bromage H, Warren ME, Borchers CH, Tempst P, Zhang Y. Histone demethylation by a family of JmjC domain-containing proteins. Nature. 2006;439:811–6. doi: 10.1038/nature04433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker J, Bownes M. The expression of histone genes during Drosophila melanogaster oogenesis. Dev Genes Evol. 1998;207:535–41. doi: 10.1007/s004270050144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whalen AM, Steward R. Dissociation of the dorsal-cactus complex and phosphorylation of the dorsal protein correlate with the nuclear localization of dorsal. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:523–34. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.3.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao B, Jing C, Kelly G, Walker PA, Muskett FW, Frenkiel TA, Martin SR, Sarma K, Reinberg D, Gamblin SJ, Wilson JR. Specificity and mechanism of the histone methyltransferase Pr-Set7. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1444–54. doi: 10.1101/gad.1315905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Reinberg D. Transcription regulation by histone methylation: interplay between different covalent modifications of the core histone tails. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2343–60. doi: 10.1101/gad.927301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trimethylated histone H4-K20 is associated with chromatin in early embryos. Western blots of soluble and chromatin bound fractions from 0–3 hour old embryos probed with anti-trimethylated histone H4-K20.