Abstract

The impact of male-to-female intimate partner violence (IPV) research on participants is unknown. A measure of impact was given to participants in an IPV study to assess systematically the impact of completing questionnaires, engaging in conflict conversations, and being interviewed individually about anger escalation and de-escalation during the conversations. Participants completed the six question, Likert-scaled, impact measure. Both male and female participants rated the impact of the study as helpful to them personally and to their relationships. Female participants rated different segments of the study as more helpful to themselves and their relationships, while male participants did not find any segment of the study to have a different impact than other segments.

Keywords: Ethics, Participation Impact, Intimate Partner Violence, Couples, Observational Research

Male-to-female intimate partner violence (IPV) occurs in between 5.2 and 13.6% of American couples each year (Shafer, Caetano & Clark, 1998). IPV elevates victims’ risk of physical injury (O’Leary, 1999; Thompson, Saltzman & Johnson, 2001;), chronic and acute physical problems (Coker et al., 2000), and myriad psychological disorders (e.g., Major Depressive Disorder, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, anxiety disorders and substance abuse; Cascardi et al., 1995; Magdol et al., 1998). The prevalence and impact of IPV has evoked the interest of advocates, clinicians, and researchers alike, resulting in over 5,600 published works listed in PsycINFO.

An important but nearly unstudied element in this burgeoning area is the meta-topic of research participation’s effect on research participants. IPV is considered a “sensitive topic” (i.e., one that might pose considerable threat to both participants and researchers; Lee, 1993). Possible harm to participants in research studies on sensitive topics is a concern of Institutional Review Boards (IRBs), whose primary goal is to ensure the safety of research participants (National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, 1978). For many studies of IPV, it is difficult to determine whether the procedures confer “minimal risk” or “more than minimal risk.” Minimal risk means that the chance and extent of harm that might result from research participation are not any greater than normally encountered during daily activities or during standard psychological or physical examinations or assessments (45 CFR 46.102i, 2001). Sections 46.111a1 and 46.111a2 of the Department of Health and Human Service’s Code of Federal Regulations expand upon procedures researchers can follow to minimize risks and assess the cost/benefit ratio of research participation (45 CRF 46.111a1, 45 CRF 46.111a2, 2001). Procedures commonly used in IPV research that, under many conditions, would likely confer minimal risk are questionnaires (Cascardi & Vivian, 1995; Medina et al., 2001), interviews (Lawson, 2003; Murphy et al., 2005), and problem solving discussions (for reviews see Heyman, 2001; Gottman, 1998).

However, is minimal risk a correct assumption for these research methods? Most researchers formulate their opinions about the risk involved in conducting such research through informal means (e.g., past experience, perceived norms within an area of study, discussions with colleagues). When little is known about the impact of a study, researchers may infer minimal risk based on these informal means, whereas IRBs may assume “worst case scenarios” (Oakes, 2002) in an attempt to protect participants. IRBs may then require that investigators take additional steps to mitigate these perceived risks. However, typically neither the IRB nor the investigator knows whether such steps (often time-consuming and/or cumbersome to both investigators and participants) are necessary as study designers and reviewers typically lack systematic, scientific studies on which to base such decisions.

In this study, we assessed the impact of questionnaires, naturalistic conversations, and interviews. Our sample comprised couples recruited through random digit dialing to be representative of four groups of couples (happy/non-aggressive, unhappy/non-aggressive, unhappy/aggressive, and happy/aggressive). The questionnaire segment involved partners privately completing a variety of measures about themselves and their relationships. The conversation segment involved partners discussing three conflictual topics. The interview segment involved partners separately discussing with experimenters their ratings of anger escalation and de-escalation during the conversations. A set of ratings was collected at the end of the study to assess the impact of each segment of the study on participants.

We expected that our community study of IPV would involve minimal risk (i.e., neutral to positive impact for most, slightly negative impact for very few). We wished to test the typical conjecture (among IRB members and others) that participants in relationships involving IPV would be more negatively impacted by the study procedures than would non-IPV participants, given concerns that violence-related questionnaires could be re-traumatizing, conversations could be more affectively charged, and that probing interviews about anger could be more upsetting. Although we had no reason to assume that participants would be differentially affected by each section of the study, the conversation segment, because of its naturalistic quality, conceivably could pose more risk than other segments of the study for IPV couples compared to non-IPV couples. Finally, we hypothesized, in light of precautionary measures taken, that no participants would report interpartner aggression as a result of participation.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 85 couples (170 particpants) who completed the study in its entirety, including the questionnaire upon which this paper is based, and whose impact-of-study questionnaire could be linked to their laboratory data.1 An additional 221 participants completed the study in its entirety but had impact-of-study questionnaires that could not be linked to their laboratory data.. In addition to these 391 participants, another 191 participants completed the in-lab portion of the study (questionnaires, conversations, and interviews) but did not complete the impact-of-study questionnaire.

Couples were recruited using random digit dialing; in our procedure, a computer randomly generated four-digit numbers that were paired with three-digit exchanges associated with areas within a 45-minute drive of the University. Research assistants then dialed these computer generated numbers. An adult in the household, if married or cohabitating for at least one year, was asked (among others) a few demographic questions; the Quality of Marriage Inventory (QMI; Norton, 1983), which assesses relationship happiness; and five minor partner physical assault questions from the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2; Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy & Sugarman, 1996), which assesses physical aggression between partners. These questions were used to screen potential participants; those who qualified were offered the opportunity to participate in the laboratory study.

Overall, our RDD survey sample was fairly representative of the county population, and and final participants did not substantially differ from those who qualified for the study but were not part of the final sample (see Slep, Heyman, Williams, Van Dyke & O’Leary, 2005 for a more detailed description of procedures and assessments of representativeness).

Participating couples were classified as belonging to one of four groups based on couples’ in-laboratory scores on the entire CTS2 and QMI: (a) happy/non-IPV; (b) distressed/non-IPV; (c) distressed/IPV; and (d) happy/IPV2. Partners’ combined CTS2 reports had to indicate at least two minor acts of physical aggression (or one severe act) by the man against the woman during the past year to be classified as IPV (see Heyman, O’Leary & Jouriles, 1995 and Margolin and colleagues [e.g., Margolin, Burman & John, 1989; Margolin, John & Gleberman, 1988] for similar operationalizations). For the couple to be classified as distressed, one partner had to score below the clinical threshold of unhappiness (97 on the Dyadic Adjustment Scale, DAS; Spanier, 1976, converted to a QMI score of 29 using the Heyman, Sayers, and Bellack, 1994 conversion formula). To be classified as happy, one partner had to score at or above the median threshold for happiness, (114 on the DAS — from a large, cross-investigator dataset, Eddy, Heyman, & Weiss, 1991 — converted to a QMI score 34). Couples were disqualified from the study because one partner was in the distressed range and the other was in the happy range.

Procedure

Participants came to the laboratory for four hours (two 2-hour sessions or one 4-hour session). When couples arrived, they were greeted and the protocol was explained, including the purpose, procedures, confidentiality, participant rights, and possible risks associated with the study. Consent forms were discussed and signed by willing participants. Once consent was given by both participants, participants went to separate rooms where they filled out questionnaires. Questionnaires included demographics, changes the participant desired of his/her partner, contentment with partner, history of IPV, attitudes about IPV, areas of contention in the relationship, and history of sexual behaviors.

After participants completed initial questionnaires, they were asked to discuss ways in which they would like their partners to change (3 conversations total, 2 topics chosen by the wife3 and 1 by the husband, in the interest of time) based on their responses to the questionnaire about partner change. Immediately before the conversation, participants filled out a brief questionnaire assessing their expectancies about the conversation. Participants were then instructed to discuss the topic chosen by the wife for 10 minutes in a manner that represented their conversations “at their best.” Immediately after the conversation, each spouse completed a questionnaire about their impressions of the conversation. To determine how typical the conversations were for couples, participants completed a measure assessing the typicality of the conversation (Foster, Caplan & Howe, 1997) after each conversation. After completing the post-conversation questionnaire, participants separately watched video playbacks of their partners during the conversations and rated their own anger levels on a moment-by-moment basis. Next, partners were interviewed by an experimenter about two segments they rated as their greatest anger escalations. After the interview, participants again watched the video and identified periods where they attempted to de-escalate themselves, their partners, or the conversations. Participants were then interviewed about their own and their partners’ de-escalation attempts. After the second interview, participants rejoined one another to discuss the second topic, which was also chosen based on the wives’ questionnaire responses. Participants were instructed to discuss this topic as they typically would at home. Procedures for the second conversation were identical to those of the first. After the anger ratings, de-escalation ratings, and interviews were completed, the couples once again reconvened to discuss the husbands’ topic as they typically would at home. No video playbacks, ratings or interviews were completed after the final conversation.

Immediately after the third conversation, couples separated again to finish their questionnaire packets. Upon completing questionnaires, participants completed a series of Likert ratings about their current emotional states and feelings toward their partners. When all in-lab questionnaires were completed, participants were debriefed about the study and paid, any additional questions were answered, and they were either given or mailed an additional packet of questionnaires. This final packet included questionnaires about general demographics; relationship conflict; family relations; violence in the family-of-origin and in dating relationships, individual emotional adjustment, perceived self-efficacy and perceived control in the relationship; and the impact of the study on the participant and the relationship, which was used for this paper.

Precautions were taken to prevent anyone from leaving the lab upset or angry. Before the study began, couples were told about their right to stop the study or any part of it early without penalty. Discussion topics for the conversation segment of the study were chosen based on participants’ responses to a questionnaire and participants had the opportunity to refuse any topics that they did not want to discuss. In the couple of cases when participants declined a topic, we randomly selected another topic based on their responses to the questionnaire. At the end of the study, participants completed a short questionnaire about their current emotional states. If negative states (e.g., anger, depression, upset) were indicated, an experimenter spoke with the participant to discuss her/his emotional state and ability to cope. Although not needed during the study, procedures were in place to respond to significant distress, anger, or fear. Finally, during the debriefing, a list of family resources (i.e., community agencies, hotlines, mental health service providers) was given to all couples.

Measures

The typicality measure (Foster, Caplan & Howe, 1997) was completed by both partners after each 10-minute conversation. The measure asked participants how typical different aspects of the conversation were on a 5-point scale ranging from much less than usual (1) to much more than usual (5). Following Foster et al.’s factor analysis, we created two dimensions of typicality: social support (5 items) and social undermining (3 items).

Six 7-point Likert-scale questions, developed for this study and included in the take-home packet, assessed the impact of the study from harmful (1) to helpful (7). The first three questions assessed how each segment of the study — questionnaires, conversations, interviews — impacted the respondent personally; the next three questions assessed how each segment of the study impacted his/her relationship. Printed beneath the Likert-scaled questions was the word “comments” and several inches of space for comments. A final question asked whether the participant would like one of the principal investigators to contact them to discuss their participation.

Of the 170 participants (85 couples) included in the analyses, 84 women and 84 men completed the questions about personal impact (Cronbach’s a = .86 and .90, respectively). Seventy-two women and 69 men completed the questions about relationship impact (a = .90 and .87, respectively). When data were missing for the personal impact ratings or relationship impact ratings for one partner in a couple, HLM conducted couple-level analyses based on the data from the other partner. Participants were not included in analyses if data was missing for both partners.

Results

Generalizability

To determine if those included in the HLM analyses differed from those not included due to missing data, a series of 4x2 between-subjects univariate ANOVAs were conducted comparing analyzed and non-analyzed participants by group (happy, non-IPV; distressed, non-IPV; distressed, IPV; happy, IPV) on each of the following variables: age; family income; education; relationship satisfaction; husband-to-wife physical, emotional, and sexual aggression; and wife-to-husband to physical, emotional, and sexual aggression. There was a significant main effect for inclusion in analyses for husband-to-wife sexual maltreatment F (1,480) = 7.86, p < .01, ηp2 = .02. Non-IPV couples who were included in analyses, compared to those who were not, reported less husband-to-wife sexual maltreatment. IPV couples who were included in analyses, compared to those who were not, reported more husband-to-wife sexual maltreatment.

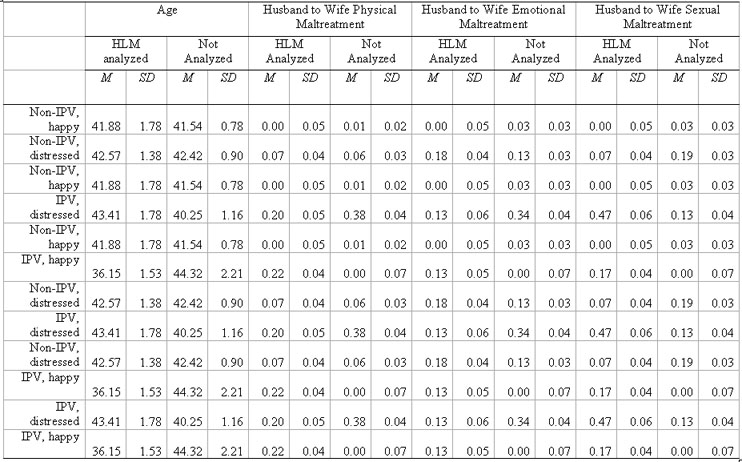

Group-by-inclusion-in-analyses interactions were not significant for education; family income; husbands’ satisfaction; wives’ satisfaction; and wife-to-husband emotional maltreatment. Significant interactions were found for age; husband-to-wife physical, emotional, and sexual maltreatment; and wife-to-husband physical and sexual maltreatment (see Table 1). To determine the nature of these significant interactions, 2x2 between-subjects univariate ANOVAs were run to compare respondents to non-respondents by group (see Table 2). In some groups, participants included in analyses had higher levels of reported husband-to-wife or wife-to-husband aggression than non-analyzed participants, while in other cases non-analyzed participants had higher levels of reported husband-to-wife or wife-to-husband maltreatment than participants included in the HLM analyses. Means and standard deviations of each group by response status are also reported in Table 3.

Table 1.

4x2 Between Subjects Univariate Analysis of Variance for Demographics, Marital Satisfaction Scores, and Physical Aggression Ratings for the Response by Group Interaction

| Source | n | df | F | ηp² |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 582 | 3 | 3.81** | 0.02 |

| Family Income | 534 | 3 | 0.30 | 0.00 |

| Education Level | 581 | 3 | 0.72 | 0.00 |

| Wife relationship satisfaction (QMI) | 582 | 3 | 1.39 | 0.01 |

| Husband relationship satisfaction (QMI) | 582 | 3 | 1.50 | 0.01 |

| Husband to wife physical maltreatment | 482 | 3 | 5.02** | 0.03 |

| Husband to wife emotional maltreatment | 482 | 3 | 4.23** | 0.03 |

| Husband to wife sexual maltreatment | 482 | 3 | 11.24*** | 0.07 |

| Wife to husband physical maltreatment | 482 | 3 | 2.64* | 0.02 |

| Wife to husband emotional maltreatment | 482 | 3 | 0.18 | 0.00 |

| Wife to husband sexual maltreatment | 482 | 3 | 3.78* | 0.02 |

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Note. QMI = Quality of Marriage Inventory (Norton, 1983). The within groups df are n -2 for each comparison..

Table 2.

2x2 Simple Between-subjects Univariate ANOVAs for Group-by-Response Interaction Comparisons

| Age | Husband to Wife Physical | Husband to Wife Emotional | Husband to Wife Sexual | Wife to Husband Physical | Wife to Husband Sexual | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groups | Df | F | df | F | df | F | df | F | Df | F | df | F |

| Non-IPV, happy by | 1 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.24 | 1 | 1.49 | 1 | 1.68 | 1 | 3.83 | 1 | 5.40* |

| Non-IPV, distressed | ||||||||||||

| Non-IPV, happy by | 1 | 0.97 | 1 | 3.62 | 1 | 4.62* | 1 | 22.91*** | 1 | 3.91* | 1 | 0.27 |

| IPV, distressed, | ||||||||||||

| Non-IPV, happy by | 1 | 6.36* | 1 | 11.17** | 1 | 5.69* | 1 | 7.99** | 1 | 1.47 | 1 | 0.49 |

| IPV, happy | ||||||||||||

| Non-IPV, distressed by | 1 | 1.30 | 1 | 3.64 | 1 | 5.96* | 1 | 20.01*** | 1 | 0.49 | 1 | 5.33* |

| IPV, distressed | ||||||||||||

| Non-IPV, distressed by | 1 | 6.95** | 1 | 5.08* | 1 | 6.13* | 1 | 6.77* | 1 | 3.89 | 1 | 3.88 |

| IPV, happy | ||||||||||||

| IPV, distressed by | 1 | 10.73** | 1 | 6.80* | 1 | 0.50 | 1 | 1.63 | 1 | 2.90 | 1 | 0.09 |

| IPV, happy | ||||||||||||

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Note. IPV = Intimate Partner Violence.

Table 3.

Means and Standard Deviations for Group-by-Response Interaction Comparisons

Note. IPV = Intimate Partner Violence. HLM = Hierarchical Linear Modeling. From Hierchical Linear Models, by A.S. Bryk and S. W. Raudenbush, 1992, Sage.

Descriptive Statistics

The average impact rating of the study overall (all segments of the study for personal and relationship impact considered) was M = 5.17 (SD = .98) for men and M = 5.34 (SD = .91) for women. The percentage of mean scores at or above 4.00 (no impact) was 95.2% for men and 96.4% for women. Far from being harmed by being asked sensitive questions and participating in conflictual conversations, we found significantly positive impact ratings for both men and women (men, t(84) = 10.97, p<.001; women, t(84) = 13.46, p<.001).

Hierarchical Linear Modeling (HLM)

Data collected for this study are intrinsically non-independent because husbands and wives are naturally part of a couple. Husbands and wives interacted during the conversation segment, so the ratings impact-of-study ratings are not independent. HLM (Bryk & Raudenbush, 1992) was therefore used to examine the relationship between group (happy/non-IPV, distressed/non-IPV; distressed/IPV; and happy/IPV) and impact ratings across two levels of analysis: the individual level (level 1) and the couple level (level 2). The following Level 1 within-individuals model was used:

where Yij is the impact rating for individual i in couple j; WIFE and HUSBAND are the level-1 predictors. WIFE is a dummy variable that is coded 0 for husbands and 1 for wives; HUSBAND is a dummy variable that is coded 0 for wives and 1 for husbands. β1j is the slope for wives, β2j is the slope for husbands, and Rij is the error term. Level-2 contains crossed variables of happy vs. distressed and IPV vs. non-IPV. The following level 2 equations were used:

where β1j and β2j are Level-1 coefficients that vary across couples in the level-2 model as a function of the grand means, γ10 and γ20; predictor variables; and random error, u1j and u2j. γ10 is the average expected impact rating for wives across all groups when aggression and happiness ratings are held constant. γ20 is the average expected impact rating for husbands across all groups when aggression and happiness ratings are held constant. γ11 is the mean effect of AGGRESSIVE on β1j, γ12 is the mean effect of HAPPY on β1j, and γ13 is the mean effect of INTERACTION on β1j. γ21 is the mean effect of AGGRESSIVE on β2j, γ22 is the mean effect of HAPPY on β2j, and γ23 is the mean effect of INTERACTION on β2j. γ11, γ12, γ13, γ21, γ22, and γ23 are Level-2 coefficients. AGGRESSIVE is a level-two predictor variable that is dummy coded as 0 for non-IPV and 1 for IPV couples. HAPPY is a level-two predictor variable that is dummy coded as 0 for distressed couples and 1 for happy couples. INTERACTION is the final level-two predictor variable that is dummy coded as 0 for happy/non-IPV couples and distressed/IPV couples; and 1 for happy/IPV couples and distressed/non-IPV couples.

The HLM 6.02a student version software (Raudenbush, Bryk & Congdon, 2005) was used to estimate the means and standard errors for the above equations. The significance of the coefficients was tested with t-tests. The results from the HLM analyses are reported in table 4. No significant gender differences for impact ratings were found using HLM when participants were classified in terms of both aggression (IPV, non-IPV) and happiness (happy, distressed).

Table 4.

Hierarchical Linear Modeling (HLM) Results Using Participant Grouping Variables to Predict Impact Ratings.

| Personal impact of questionnaires | Personal impact of conversations | Personal impact of interviews | Relationship impact of questionnaires | Relationship impact of conversations | Relationship impact of interviews | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | coef | SE | t | coef | SE | t | coef | SE | T | coef | SE | t | coef | SE | t | coef | SE | T |

| Wife | 5.16 | 5.21 | 5.04 | 4.88 | 5.20 | 4.84 | ||||||||||||

| Intercept | ||||||||||||||||||

| Aggressive | 0.43 | 0.25 | 1.71 | 0.44 | 0.22 | 1.99* | 0.49 | 0.24 | 2.02* | 0.59 | 0.29 | 2.07* | 0.33 | 0.24 | 1.37 | 0.63 | 0.27 | 2.30* |

| Happy | −0.04 | 0.25 | −0.15 | 0.14 | 0.22 | 0.65 | −0.10 | 0.24 | −0.39 | 0.05 | 0.29 | 0.18 | 0.30 | 0.24 | 1.23 | 0.02 | 0.27 | 0.08 |

| Interaction | 0.10 | 0.25 | 0.41 | 0.12 | 0.22 | 0.56 | 0.00 | 0.24 | 0.00 | −0.02 | 0.29 | −0.07 | 0.03 | 0.24 | 0.14 | −0.17 | 0.27 | −0.62 |

| Husband | 4.86 | 4.86 | 4.65 | 4.68 | 5.11 | 4.97 | ||||||||||||

| Intercept | ||||||||||||||||||

| Aggressive | 0.43 | 0.25 | 1.73 | 0.32 | 0.26 | 1.22 | 0.41 | 0.25 | 1.62 | 0.53 | 0.27 | 1.96 | −0.04 | 0.26 | −0.15 | 0.39 | 0.26 | 1.48 |

| Happy | 0.08 | 0.25 | 0.32 | 0.44 | 0.26 | 1.67 | 0.18 | 0.25 | 0.70 | 0.05 | 0.27 | 0.20 | 0.39 | 0.26 | 1.49 | −0.10 | 0.26 | −0.39 |

| Interaction | 0.10 | 0.25 | 0.41 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.97 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.95 | 0.00 | 0.27 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.26 | −0.02 | −0.07 | 0.26 | −0.28 |

p < .05,

p < .01

There was a significant main effect for the AGGRESSIVE predictor for personal impact from the conversation and interview segments of the study, and for relationship impact from the questionnaire and interview segments of the study for wives only. In other words, IPV female participants rated the impact of the conversation and interview segments of the study on themselves personally and the impact of the questionnaires and interviews on their relationships as significantly more helpful than non-IPV female participants did. To determine if there were significant differences between groups, we dummy coded each group (happy/non-IPV, distressed/non-IPV, distressed/IPV, and happy/IPV) and compared their means for personal impacts of the conversations and interviews and relationship impacts of the questionnaires and interviews. Results are reported in table 5. The main effect of aggression for personal impact of the conversations was due to a significantly higher mean impact rating for happy/IPV women than for happy/non-IPV women. The main effect of aggression for relationship impact of the questionnaires was due to a significantly higher mean for happy/IPV women than for distressed/non-IPV women. The main effect of aggression for relationship impact of the interviews was driven by significantly higher mean impact ratings for distressed/IPV women than for distressed/non-IPV and for happy/IPV women than for distressed/non-IPV women.

Table 5.

Means and T-ratios for Hierarchical Linear Modeling Comparisons Between Groups for Wives

| Personal impact of conversations

|

Personal impact of interviews

|

Relationship impact of questionnaires

|

Relationship impact of interviews

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groups | M | SE | t | M | SE | t | M | SE | t | M | SE | t |

| Non-IPV, happy to | 5.35 | .27 | −0.07 | 4.94 | .27 | 0.27 | 4.93 | .35 | −0.21 | 4.86 | .32 | −0.59 |

| Non-IPV, distressed | 5.33 | 5.03 | 4.86 | 4.67 | ||||||||

| Non-IPV, happy to | 5.35 | .39 | 0.84 | 4.94 | .35 | 1.52 | 4.93 | .48 | 1.13 | 4.86 | .45 | 1.35 |

| IPV, distressed | 5.64 | 5.52 | 5.47 | 5.47 | ||||||||

| Non-IPV, happy to | 5.35 | .32 | 1.87* | 4.94 | .30 | 1.37 | 4.93 | .39 | 1.47 | 4.86 | .39 | 1.18 |

| IPV, happy | 5.91 | 5.43 | 5.50 | 5.32 | ||||||||

| Non-IPV, distressed | 5.33 | .37 | 0.98 | 5.03 | .32 | 1.41 | 4.86 | .42 | 1.46 | 4.67 | .38 | 2.08* |

| to IPV, distressed | 5.64 | 5.52 | 5.47 | 5.47 | ||||||||

| Non-IPV, distressed | 5.33 | .30 | 2.21 | 5.03 | .26 | 1.24 | 4.86 | .31 | 2.05* | 4.67 | .31 | 2.10* |

| to IPV, happy | 5.91 | 5.43 | 5.50 | 5.32 | ||||||||

| IPV, distressed to | 5.64 | .41 | 0.78 | 5.52 | .34 | 0.26 | 5.47 | .45 | 0.07 | 5.47 | .44 | −0.34 |

| IPV, happy | 5.91 | 5.43 | 5.50 | 5.32 | ||||||||

p < .05,

p < .01

Note. IPV = Intimate Partner Violence.

There were no main effects for the predictor variable HAPPY for any of the outcome variables. No significant interaction effects were found using the model.

Participants’ Free-Response Comments

Thirty-five of the analyzed participants wrote comments on their surveys about the impact of the study on them personally, on their relationship, or on both.4 Two coders independently rated comments as positive, negative or neutral (ICC =.81). Comments were rated positive or negative if they were about an actual impact that the study had on the participant or their relationship. Comments were rated neutral if they were about the protocol itself (e.g. issues with typographical errors in questionnaires, liking particular experimenters). Four of the comments were coded as neutral, 28 were coded as positive, and 3 were coded as negative. The comments that were negative indicated that different parts of the procedure (conversation and interview) were uncomfortable. None of the negative comments indicated a negative impact of the conversations or interviews after the couple left the lab. The positive comments were about the beneficial impact of participation on participants’ relationships and themselves. Fourteen participants marked that they wanted to be contacted by the principal investigators. Most of these participants asked for referrals for individual or couples therapy or asked if it was possible to get personal feedback; none expressed distress about the effect of the study on them nor did any say that the study had endangered them in any way.

Typicality of Conversations

The conversations were rated on typicality of social support and typicality of undermining. Participants considered social support provided by their partners during the conversations to be greater than the “typical” rating of 3 (see Table 6). Social undermining, however, was considered by both men and women to be typical of their normal conversations (see Table 6).

Table 6.

Typicality of Conversations Based on the Dimensions of Social Support and Undermining

| Typicality of Social Support

|

Typicality of Undermining

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | df | t | n | df | t | |

| Husbands | 85 | 84 | 2.83** | 85 | 84 | −1.88 |

| Wives | 85 | 84 | 3.02** | 85 | 84 | −1.76 |

p < .05,

p < .01

Discussion

Systematic data on the impact of studies of IPV benefits both researchers and IRBs by informing them of the real risks and benefits involved in such studies. The results from our impact questionnaire indicated that our study was viewed by participants as helpful or neutral by 95.2% of male participants and 96.4% of female participants. The finding that men and women rated their overall participation as having a significantly positive impact on themselves and their relationships leads us to believe that our assumption of minimal risk is correct.

IPV men did not differ from non-IPV men in their ratings of the study impact. This finding suggests that regardless of IPV status, the study had a consistent impact on male participants. Women in relationships with IPV men rated their participation in the study as significantly more helpful than non-IPV women on four of the six Likert scale questions. This finding runs counter to the perception of many IPV researchers that those in IPV relationships are at highest risk of harmful impacts. These women may have benefited most from the study because they were able to think about many facets of their relationships and discuss problematic issues for ten undisturbed minutes in a controlled, putatively safe environment.

Although we hypothesized that the conversation was the segment of the study with the most potential for negative impact, IPV participants, compared with non-IPV participants, found the conversation portion of the study to be more helpful or no different than other parts of the study. For some couples, thinking about or discussing aspects of their relationships and themselves in a neutral environment free of distractions may have been beneficial to them personally and to their relationships. For certain individuals, seeing themselves on the video playbacks made them aware of how they sounded or looked in conflict situations, which had a positive impact on them or on their relationship (as reported in the comments section of the impact questionnaire).

In terms of the typicality of the conversations, participants considered social support provided by their partners during the conversations to be greater than “typical,” indicating that participants may have been a bit more agreeable or pleasant than normal during the in lab conversations; however, they did not differ from typical on their perception of their partners’ undermining behaviors. Therefore, we think that the conversations were generally as negative to what participants experience outside the lab.

No violence occurred during the study, and no respondents reported violence as a result of participation. Most negative comments were not about the impact of the study but were critiques of the study itself or were off-topic comments. Participation was minimally distressing for a few individuals who felt that portions of the study itself were uncomfortable, but mentioned nothing of aftereffects. In addition, a couple of participants rated the study as harmful but qualified their rating in the comments section by noting that the study helped them realize that they were personally unhappy because of their relationships. Although the study was harmful, in that sense, to their relationships, they reported that the study was helpful to them personally.

IPV researchers working with community samples should continue their research with confidence knowing that 87% of male participants and 90.5% of female participants benefited from participating in such a study, and 8.2% of male participants and 5.9% of female participants rated the impact of the study as neutral. The implications of these results are that observational studies of couples conflict, even with IPV couples, do not necessarily result in distress or aggression.

Limitations and Future Research

One limitation of our study was that not all participants in the main study were able to be included in this study of participation impact. Sixty-seven percent of all participants completed the impact questionnaire. Of the participants who did complete the questionnaire, only 43% of the data could be linked to both members of the couple and to participant group (happy/non-IPV, distressed/non-IPV, distressed/IPV, happy/IPV). Our comparisons between those included and not included in the HLM analyses revealed some differences, especially in terms of maltreatment; however, we believe that our analyzed sample is fairly generalizable to our entire sample. The differences that we did find had small to medium effects (Cohen, 1977) and did not vary systematically (e.g., in some effects, HLM-analyzed participants were higher functioning than non-analyzed participants within a group, whereas in other effects analyzed participants were lower functioning than non-analyzed participants within the same group). It is important to note that our study was of couples recruited from the general community via random digit dialing; our results might not generalize to other populations (e.g., clinical, court-mandated, or sheltered populations).

Another limitation of our study was that the questionnaire queried impact of the study on a scale of harmful to helpful. These words were descriptive of the information we sought to gather about the effect of the study on participants; however, participants may not have paid close attention to the terms, regarding the scale as negative to positive. If we used other descriptive terms to create more rating scales (such as unpleasant to enjoyable or negative to positive), we might have found that participants considered a portion of the study to be unpleasant in terms of enjoyment but neutral in terms of harm. In addition, only 21% of participants wrote comments on their questionnaires. More comments would give us a fuller picture of why people rated the study as they did.

Future research on IPV should include measures of study impact to increase the amount of systematic data we have on the effects of such studies on participants. Based on our findings, the previous criterion of minimal harm is justifiable for research on community samples of partner aggression including questionnaire, conversation, or interview measures. We believe that our finding that minimal risk applies to community-based observational studies of IPV will extend to studies of other sensitive topics in the general population. In their study of research impact on survivors of traumatic experiences, Griffin, Resick, Waldrop, and Mechanic (2003) found that survivors regarded their participation in research as interesting and helpful. Future studies on partner violence and other sensitive topics are needed to replicate and extend our findings and those of Griffin and colleagues. Systematic data collected about the impact of research on several sensitive topics would be helpful for IRBs, funding agencies, and researchers in determining the risk and the cost-benefit ratio of such research.

Acknowledgments

The authors would especially like to thank Jean-Philippe Laurenceau for his statistical consultation on hierarchical linear modeling.

Footnotes

This research was supported in part by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH57779).

Daniela J. Owen, Department of Psychology, State University of New York at Stony Brook; Richard E. Heyman, Department of Psychology, State University of New York at Stony Brook; Amy M. Smith Slep, Department of Psychology, State University of New York at Stony Brook.

To maintain confidentiality of all participants, we did not use participant numbers on questionnaires that participants completed outside of the laboratory. We linked participants by their participant number to a new number on the take-home questionnaires. When questionnaires were returned to us, the new data was included with the rest of the participant’s data, and the two numbers were unlinked. Due to investigator errors, connecting the take-home measure used for this study to the original participant was not always possible.

The number of participants in each group for whom data from the impact-of-study questionnaire were analyzed (N = 170) is not equal to or proportionate to the number of participants in each group collected for the entire study (N = 582) because, as noted in the procedures subsection, the impact questionnaire was added to the study after it was in progress, and proportionally more of some groups’ data were collected in later stages of the study.

Couples had to be married or cohabiting to qualify. Because the vast majority were married, for convenience we will refer to “husbands” and “wives” regardless of marital status.

No comments regarding harm resulting from the study were made on any of the questionnaires that were returned by not included in the final sample of HLM-analyzed participants. Comments regarding helpfulness and harmfulness of the study were similar to those included on questionnaires from HLM-analyzed participants discussed above.

References

- Bryk, A. S., & Raudenbush, S. W. (1992). Hierarchical Linear Models Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Cascardi M, O’Leary KD, Schlee KA, Lawrence EE. Major depressive disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder in physically abuse women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:616–623. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.4.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cascardi M, Vivian D. Context for Specific Episodes of Relationship violence: Gender and Severity of Violence Differences. Journal of Family Violence. 1995;10:265–293. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. (1977). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences New York: Academic Press.

- Coker AL, Smith PH, Bethea L, King MR, McKeown RE. Physical health consequences of physical and psychological intimate partner violence. Archives of Family Medicine. 2000;9:451–457. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.5.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DHHS Protection of Human Subjects, 45 C.F.R. § 46.102 (2001).

- DHHS Protection of Human Subjects, 45 C.F.R. § 46.111 (2001).

- Eddy JM, Heyman RE, Weiss RL. An empirical evaluation of the Dyadic Adjustment Scale: Exploring the differences between marital "satisfaction" and “adjustment. Behavioral Assessment. 1991;13:199–220. [Google Scholar]

- Foster DA, Caplan RD, Howe GW. Representativeness of observed couple interaction: Couples can tell, and it does make a difference. Psychological Assessment. 1997;9:285–294. [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM. Psychology and the study of marital processes. Annual Review of Psychology. 1998;49:169–197. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin MG, Resick PA, Waldrop AE, Mechanic MB. Participation in trauma research: Is there evidence of harm? Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2003;16:221–227. doi: 10.1023/A:1023735821900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman RE. Observation of couple conflicts: Clinical assessment applications, stubborn truths, and shaky foundations. Psychological Assessment. 2001;13:5–35. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.13.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman RE, O’Leary KD, Jouriles EN. Alcohol and aggressive personality styles: Potentiators of serious physical aggression against wives? Journal of Family Psychology. 1995;9:44–57. [Google Scholar]

- Heyman RE, Sayers SL, Bellack AS. Global marital satisfaction versus marital adjustment: An empirical comparison of three measures. Journal of Family Psychology. 1994;8:432–446. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson DM. Incidence, explanations, and treatment of partner violence. Journal of Counseling & Development. 2003;81:19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, R.M. (1993). Doing research on sensitive topics London: Sage.

- Magdol L, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Silva PA. Developmental antecedents of Partner abuse: A prospective-longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:375–389. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.3.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolin G, Burman B, John RS. Home observations of marital couples reenacting naturalistic conflicts. Behavioral Assessment. 1989;11:101–118. [Google Scholar]

- Margolin G, John RS, Gleberman L. Affective responses to conflictual discussion in violent and nonviolent couples. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1988;56:24–33. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina AM, Mejia VY, Schell AM, Dawson ME, Margolin G. Startle reactivity and PTSD symptoms in a community sample of women. Psychiatry Research. 2001;101:157–169. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(01)00221-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CM, Winters J, O'Farrell TJ. Alcohol Consumption and Intimate Partner Violence by Alcoholic Men: Comparing Violent and Nonviolent Conflicts. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:35–42. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. (1978). The Belmont Report: Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research (DHEW Publication No. OS 78-0012). [PubMed]

- Norton R. Measuring marital quality: A critical look at the dependent variable. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1983;45:141–151. [Google Scholar]

- Oakes JM. Risks and wrongs in social science research: An evaluator’s guide to the IRB. Evaluation Review. 2002;26:443–479. doi: 10.1177/019384102236520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD. Developmental and affective issues in assessing and treating partner aggression. Clinical Psychology: Science & Practice. 1999;6:400–414. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush, S., Bryk, A, & Congdon, R. (2005). Hierarchical Linear and Nonlinear Modeling (Version 6.02a) [Computer software]. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International.

- Schafer J, Caetano R, Clark CL. Rates of intimate partner violence in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88:1702–1704. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.11.1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slep, A.M.S., Heyman, R.E., Williams, M.C., Van Dyke, C.E., & O’Leary, S.G. (2005). Using Random Telephone Sampling to Recruit Generalizable Samples for Family Violence Studies Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Spanier GB. Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage & the Family. 1976;38:15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and Preliminary Psychometric Data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson MP, Saltzman LE, Johnson H. Risk factors for physical injury among women assaulted by current or former spouses. Violence Against Women. 2001;7:886–899. [Google Scholar]