Abstract

Background

Anal sphincter defects have been shown to increase pressure asymmetry within the anal canal in patients with fecal incontinence. However, this correlation is far from perfect, and other factors may play a role. The goal of this study was to assess the impact of rectal prolapse on anal pressure asymmetry in patients with anal incontinence.

Methods

44 patients, (42 women, mean age: 64 (11) years), complaining of anal incontinence, underwent anal vector manometry, endo-anal ultrasonography (to assess sphincter defects) and pelvic viscerogram (for the diagnosis of rectal prolapse). Resting and squeeze anal pressures, and anal asymmetry index at rest and during voluntary squeeze were determined by vector manometry.

Results

Ultrasonography identified 19 anal sphincter defects; there were 9 cases of overt rectal prolapse, and 14 other cases revealed by pelvic viscerogram (recto-anal intussuception). Patients with rectal prolapse had a significantly higher anal sphincter asymmetry index at rest, whether patients with anal sphincter defects were included in the analysis or not (30 (3) % versus 20 (2) %, p < 0.005). Among patients without rectal prolapse, a higher anal sphincter asymmetry index during squeezing was found in patients with anal sphincter defects (27 (2) % versus 19 (2) %, p < 0.03).

Conclusions

In anal incontinent patients, anal asymmetry index may be increased in case of anal sphincter defect and/or rectal prolapse. In the absence of anal sphincter defect at ultrasonogaphy, an increased anal asymmetry index at rest may point to the presence of a rectal prolapse.

Background

Anal incontinence is a multi-factorial disease, associating various causes such as anal sphincter defects, pelvic nerve lesions and anatomical pelvic floor disorders. Endo-anal ultrasonography allows the identification of anal sphincter defects [1,2]; we have also observed that patients with rectal prolapse occasionally revealed an asymmetrical aspect of the sphincter.

Anal vector manometry has been claimed to allow for the identification of sphincter defects through increased anal pressure asymmetry index. Indeed, we and others [3,4] have shown that some correlation exists between the radial size of external anal sphincter defects and increased anal asymmetry index. However, this correlation is far from perfect and other factors such as rectal prolapse may be at bay to increase anal pressure asymmetry.

The goal of this study was to assess the impact of both anal sphincter defects and rectal prolapse on the anal asymmetry index as determined by anal vector manometry.

Methods

We thus studied the results of anal vector manometry performed in 44 patients (42 women and 2 men, mean age: 64 years-old, range: 23 to 79) complaining of anal incontinence, in whom the diagnostic work-up included an anal ultrasonography (EAU) (performed through the endo-anal and endo-vaginal route) and a dynamic pelvic viscerogram (PV) (barium opacification of pelvic organs), allowing the identification of patients with anal sphincter defects and / or rectal prolapse. Indeed, both situations may be missed despite a thorough clinical investigation: anal sphincter defects disclosed only by EAU are a frequent occurrence, and intra-anal rectal prolapse (or recto-anal intussuception) may be under-diagnosed by clinical examination only.

Anal incontinence was considered when patients experienced significant accidental bowel leakages of liquid or solid stools, recurrent episodes of anal soiling, or urgent stools with a retention time of less than fifteen minutes. The severity of anal incontinence symptoms was assessed using the clinical score proposed by Jorge et al [5]. Associated symptoms such as stress urinary incontinence and severe dyschesia (defined as the need of digital anal manoeuvres to obtain defecation) were also inquired after. Past surgical and obstetrical histories were obtained in all patients.

EAU was performed using a rigid 360° rotating probe with a transducer frequency of 7 or 10 MHz (Brüel & Kjaer, Naerum, Denmark): internal and external anal sphincter defects were identified as previously described [6,7], and the radial size of the defects measured.

Anal vector manometry was performed using a radial 8-lumen perfused catheter (Zynectics Medical, Inc, Salt Lake City, UT), an automated catheter-puller at 10 mm/s (Uro Synectics, Medtronic, Rueil-Malmaison, France): three pull-outs were performed through the anal canal at rest and during voluntary squeeze. The mean values for anal pressures and the anal asymmetry indexes, at rest and during voluntary squeeze, were calculated using a commercially available software (Polygram 98, Medtronic, Rueil-Malmaison, France). The anal asymmetry index is calculated by adding the 8 pressures obtained at the high pressure zone (defined as the anal region with mean pressures above 80% of the maximal mean pressure), dividing this by the maximum pressure multiplied by the number of channels and subtracting this value from 1. Values are reported as percentage values, with a perfect symmetry having a value of zero.

Pelvic viscerogram allowed for the identification of intra-anal or the confirmation of exteriorised rectal prolapse. PV consists of a dynamic X-Ray examination of the position and movements of pelvic organs at rest, during straining and squeezing with patients sitting on a chair. Filling of the rectum is obtained with a home-made barium paste (barium sulfate cooked with corn starch and water; vaginal marking is done by injection of a 20 ml syringe containing 10 ml of liquid barium sulfate (to mark the vaginal walls) and 10 ml of the barium paste to mould the vaginal cavity. Finally, the bladder is filled with 200 ml of water-soluble contrast medium (Telebrix) through a small catheter left in place during the examination. Intra-anal rectal prolapse was defined as the invagination of part of the rectal mucosa within the anal canal. A rectal invagination above the upper limit of the anal canal was not considered for the diagnosis of rectal prolapse.

Statistical analyses between groups were performed by one-way ANOVA or Chi2-test as appropriate. Results are expressed as mean (SEM), unless otherwise indicated. Statistical significance was set to be 0.05.

Results

The relevant demographic and clinical data of the 44 patients are summarized in table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population (44 patients with anal incontinence)

| Sex (Women/Men) | 42/2 |

| Mean Age (Range) | 64 (23–79) |

| past history of perineal surgery (%) | 31 (73.8 %) |

| past hysterectomy (%) | 22 (52.4 %) |

| parous women (%) | 35 (83.3 %) |

| number of vaginal deliveries (range) | 3.2 (1–11) |

| Forceps use in parous women (%) | 11 (31.4 %) |

| Mean clinical score of anal incontinence (range) | 13 (6–19) |

| Mean duration of symptoms in months (range) | 52 (3–480) |

| Associated symptoms of dyschesia (%) | 9 (20.5 %) |

| Associated symptoms of stress urinary incontinence (%) | 19 (43.2 %) |

Among the 44 patients, EAU identified 19 patients with an anal sphincter defect (43.2%): 8 isolated defects of the external sphincter, 3 isolated defects of the internal sphincter and 8 combined defects of both sphincters. Full-thickness rectal prolapse was clinically evident in 9 patients, and PV showed 14 cases of recto-anal intussuception. Although these two entities may not necessarily represent two stages of the same disease, they both impose a stress on the anal canal muscles, and are pooled as rectal prolapse cases (23 of 44 patients, 52.3%). The coexistence of both abnormalities (anal sphincter defect and rectal prolapse) was found in ten patients (22.7%).

In some patients, anal ultrasonography showed an asymmetrical aspect of the anal sphincter when a rectal prolapse was present (figure 1), or a heterogeneous thickening of the internal hyperechoic layer corresponding to the anal sub-mucosa (figure 2), while these aspects were never seen in the absence of a rectal prolapse (figure 3).

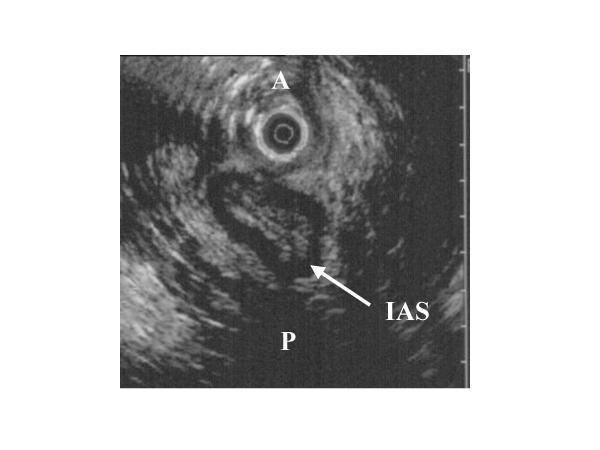

Figure 1.

Endo-vaginal ultrasonography of anal sphincter in a patient with rectal prolapse: irregular and asymmetrical appearance of the internal anal sphincter (IAS arrow), without defect (A: anterior, and P: posterior).

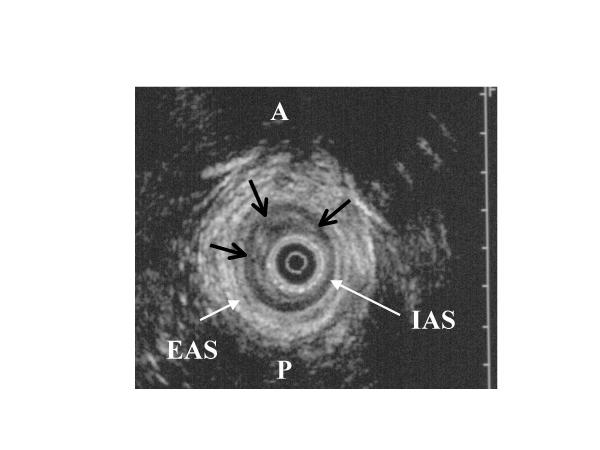

Figure 2.

Endo-anal ultrasonographic view of the anal sphincter in a patient with rectal prolapse: black arrows indicate a submucosal thickening in the anterior right and left quadrants of the internal anal sphincter (IAS: internal anal sphincter; EAS: external anal sphincter; A: anterior; P: posterior).

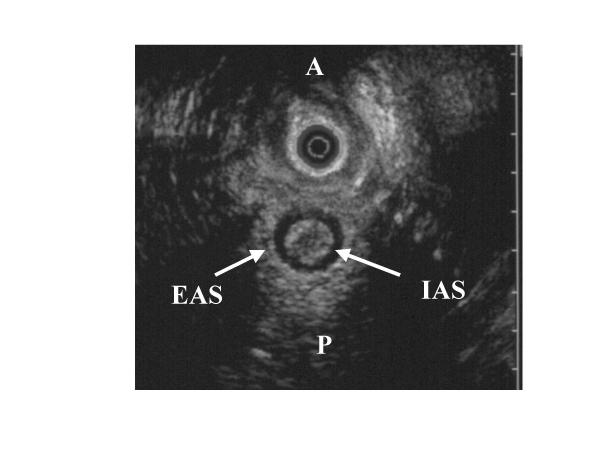

Figure 3.

For comparison, an endo-vaginal ultrasonographic view of a normal anal sphincter of a patient without rectal prolapse. (IAS: internal anal sphincter; EAS: external anal sphincter; A: anterior; P: posterior).

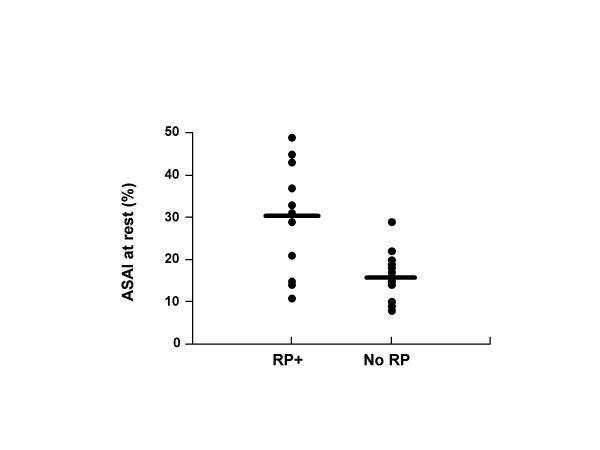

The 2 groups of patients with and without rectal prolapse did not differ in terms of age, past histories of vaginal deliveries, perineal or gynaecological surgery, score of anal incontinence, associated urinary symptoms. Severe dyschesia was observed more frequently in the rectal prolapse group (8 of 23 patients (34.8 %), versus 1 of 21 patients (4.7 %) without rectal prolapse, p < 0.04). The results of anal vector manometry are summarized in tables 2 and 3. Patients with rectal prolapse had an anal sphincter asymmetry index at rest significantly increased, while the differences were not statistically significant for the other manometric variables (table 2). With regard to the presence or absence of anal sphincter defects, the results of vector manometry were different only for the anal sphincter asymmetry index during squeezing (table 3). When taking into account only the patients without anal sphincter defects (25 patients, of whom 13 had a rectal prolapse), the anal asymmetry index at rest was still the only manometric variable significantly increased when a rectal prolapse was present (30(3)% vs 16(2) %, p < 0.03) (figure 4).

Table 2.

Results of anal vector manometry in patients with or without rectal prolapse (patients with anal sphincter defects included).

| Rectal prolapse | No rectal prolapse | p | |

| number of patients | 23 | 21 | |

| Mean (SEM) anal resting pressure (cm H2O) | 45 (7) | 67 (11) | 0.08 |

| Mean (SEM) anal squeeze pressure (cm H2O) | 88 (13) | 114 (16) | 0.2 |

| Mean (SEM) ASAI at rest (%) | 30 (3) | 20 (2) | 0.0046 |

| Mean (SEM) ASAI during squeezing (%) | 25 (2) | 20 (2) | 0.19 |

(ASAI: anal sphincter asymmetry index)

Table 3.

Results of anal vector manometry in patients with or without anal sphincter defect (patients with rectal prolapse included).

| Anal sphincter defect | Normal sphincter | p | |

| number of patients | 19 | 25 | |

| Mean (SEM) anal resting pressure (cm H2O) | 54 (10) | 56 (9) | 0.8 |

| Mean (SEM) anal squeeze pressure (cm H2O) | 93 (16) | 107 (13) | 0.5 |

| Mean (SEM) ASAI at rest (%) | 28 (3) | 23 (2) | 0.2 |

| Mean (SEM) ASAI during squeezing (%) | 27 (2) | 19 (2) | 0.024 |

(ASAI: anal sphincter asymmetry index)

Figure 4.

Individual results of anal sphincter asymmetry index at rest (ASAIr) in patients without anal sphincter defect, depending on the presence (13 patients) or the absence (12 patients) of rectal prolapse. The black bars represent the mean value in each group (p < 0.03).

The other parameters of vector manometry were not different (data not shown). Finally, the results of vector manometry were similar in patients with full thickness rectal prolapse or recto-anal intussuception, whether patients with anal sphincter defects were included or not (data not shown).

Discussion

To our knowledge, the results of this study identify for the first time the role of rectal prolapse in the determination of anal sphincter pressure asymmetry. In patients with anal incontinence, anal vector manometry has been used mainly to evaluate the existence of anal sphincter defects. Although it can not precisely locate the defect [8], in comparison with anal ultrasonography, recent studies have shown that an increased anal asymmetry index was well correlated to the presence of a large anal sphincter defect on ultrasonography [3,4]. However, an increased anal asymmetry index without anal sphincter defect is not a rare occurrence in our experience. Our results clearly demonstrate that rectal prolapse or recto-anal intussuception may also increase anal asymmetry index, in the same proportions as anal sphincter defects. This is of importance because rectal prolapse is a well known cause of anal incontinence, because the clinical diagnosis of this condition may be sometimes difficult and because a specific treatment of the prolapse may improve the symptoms of anal incontinence [9-11]. On the other hand, recto-anal intussuception may cause significant symptoms of obstructive defecation (dyschesia), which may in the long term leads to anal incontinence [12]. On a functional point of view, rectal prolapse has been shown to be associated with a decreased resting anal pressure [13-15]. Several hypotheses have been suggested to explain this manometric finding: associated pudendal neuropathy [16], functional inhibition of the mechanical activity of the anal internal sphincter [13], or associated defects of the anal sphincter [17]. From our results, we believe that the distortion of the anal sphincter induced by the rectal prolapse, as identified by anal vector manometry, may be responsible for a decreased contractile activity (functional inhibition). Interestingly, in the group of patients without anal sphincter defect, only the anal sphincter asymmetry index at rest was significantly increased when a rectal prolapse was present, while in the group of patients without rectal prolapse, only the anal sphincter asymmetry during squeezing was significantly increased when an anal sphincter defect was present (with a majority of external sphincter defects). These 2 observations indicate that rectal prolapse alters mainly the internal anal sphincter functions, while the consequences of external anal sphincter defects are as expected modifying anal voluntary squeeze.

Conclusions

Our results demonstrate that in patients with anal incontinence, an increased anal asymmetry index as determined by vector manometry may not be related to anal sphincter defects only. Rectal prolapse and recto-anal intussuception may indeed increase anal asymmetry index, especially at rest. This functional asymmetry is often seen on EAU as an heterogenous thickening of the internal sphincter muscular layer. This typical aspect should thus be looked for during EAU evaluation of anal incontinent patients, in addition to the search for anal sphincter defects. In difficult cases, defecography or pelvic viscerogram should be performed to distinguish between full thickness rectal prolapse and recto-anal intussuception.

Competing interests

None declared.

Authors' contributions

HD carried out the echographic and manometric studies, and conceived of the study. LH carried out the pelvic viscerograms. SR participated in the design of the study. XB participated in the patients' enrolment and in the design of the study. FM participated in the design of the study and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Contributor Information

Henri Damon, Email: henri.damon@wanadoo.fr.

Luc Henry, Email: luc.henry@chu-lyon.fr.

Sabine Roman, Email: sroman@ifrance.com.

Xavier Barth, Email: xavier.barth@chu-lyon.fr.

François Mion, Email: francois.mion@chu-lyon.fr.

References

- Sultan AH, Kamm MA, Talbot IC, Nicholls RJ, Bartram CI. Anal endosonography for identifying external sphincter defects confirmed histologically. Br J Surg. 1994;81:463–5. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800810349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sultan A, Nicholls R, Kamm M. Anal endosonography and correlation with in vitro and in vivo anatomy. Br J Surg. 1992;80:808–811. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800800435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fynes MM, Behan M, O'Herlihy C, O'Connell PR. Anal vector volume analysis complements endoanal ultrasonographic assessment of postpartum anal sphincter injury. Br J Surg. 2000;87:1209–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damon H, Henry L, Barth X, Mion F. Fecal incontinence in women with a past history of vaginal delivery: significance of anal sphincter defects detected by ultrasound. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:1445–51. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6448-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorge JM, Wexner SD. Etiology and management of fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:77–97. doi: 10.1007/BF02050307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law PJ, Kamm MA, Bartram CI. Anal endosonography in the investigation of faecal incontinence. Br J Surg. 1991;78:312–4. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800780315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damon H, Henry L, Valette P, Mion F. Endosonography in begnin anorectal disease. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2001;25:35–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YK, Wexner SD. Anal pressure vectography is of no apparent benefit for sphincter evaluation. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1994;9:92–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00699420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senapati A, Nicholls RJ, Thomson JP, Phillips RK. Results of Delorme's procedure for rectal prolapse. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37:456–60. doi: 10.1007/BF02076191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirocco WC, Brown AC. Anterior resection for the treatment of rectal prolapse: a 20-year experience. Am Surg. 1993;59:265–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duthie GS, Bartolo DC. Abdominal rectopexy for rectal prolapse: a comparison of techniques. Br J Surg. 1992;79:107–13. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800790205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neill ME, Parks AG, Swash M. Physiological studies of the pelvic floor in idiopathic faecal incontinence and rectal prolapse. Br J Surg. 1981;68:531–6. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800680804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farouk R, Duthie GS, MacGregor AB, Bartolo DC. Rectoanal inhibition and incontinence in patients with rectal prolapse. Br J Surg. 1994;81:743–6. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800810542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felt-Bersma RJ, Janssen JJ, Klinkenberg-Knol EC, Hoitsma HF, Meuwissen SG. Soiling: anorectal function and results of treatment. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1989;4:37–40. doi: 10.1007/BF01648548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gammarota FV, Farouk R, Duthie GS, Bartolo DC. The functional recovery of the internal anal sphincter and the restoration of continence after rectopexy for rectal prolapse. G Chir. 1992;13:527–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum EH, Stamm L, Rafferty JF, Fry RD, Kodner IJ, Fleshman JW. Pudendal nerve terminal motor latency influences surgical outcome in treatment of rectal prolapse. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:1215–21. doi: 10.1007/BF02055111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halligan S, Sultan A, Rottenberg G, Bartram CI. Endosonography of the anal sphincters in solitary rectal ulcer syndrome. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1995;10:79–82. doi: 10.1007/BF00341201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]