Abstract

Background:

acute paraquat self-poisoning is a significant clinical problem in parts of Asia, the Pacific and the Caribbean. Ingestion of large amounts of concentrated paraquat formulations results in rapid death from multi-organ failure and cardiogenic shock. Ingestion of smaller volumes often causes a delayed lung fibrosis that is fatal in most patients. Anti-neutrophil (often referred to as ‘immunosuppressive’) treatment has been recommended by various groups over the last 30 years to prevent lung fibrosis but there is no consensus on efficacy.

Aim:

to i. review the evidence for the use of immunosuppression in paraquat poisoning and ii. identify validated prognostic systems that would allow the use of data from historical control studies and the future identification of patients who might benefit from immunosuppression.

Design:

systematic review

Methods:

we searched PubMed, Embase and Cochrane databases (last search 04/11/02) for ‘paraquat’ together with ‘poisoning’ or ‘overdose’. We cross checked references and contacted experts, and searched the internet using ‘paraquat’, ‘cyclophosphamide’, ‘methylprednisolone’ and ‘prognosis’ [<www.google.com> and <www.yahoo.com>] (last checked 23/11/02).

Results:

we found ten clinical studies of immunosuppression in paraquat poisoning. One was a randomised controlled trial (RCT) but its methodology and analysis raise questions and its conclusions were acknowledged by the authors to be preliminary. Seven other studies used historical, not parallel group, controls, while two reported one and four cases each. Mortality in control and treatment groups varied markedly between studies. Three of the seven non-RCT controlled studies measured plasma paraquat; reanalysis using the most widely used prognostic indicator (evaluation of plasma paraquat concentration using Proudfoot's or Hart's curves) did not support the proposal that immunosuppression increased survival in these studies. Our analysis of sixteen studies of prognostic systems for paraquat poisoning showed that none have been independently validated in a large cohort of patients, thus raising questions regarding their reliability and accuracy.

Discussion:

the authors of the RCT have performed valuable and difficult research; at present, however, their results must be seen as hypothesis-forming rather than conclusive. Seven of the other studies used historical controls, which are associated with inflation of benefit and poor quality of evidence. One of the main constraints in these trials is the lack of a universally applicable, validated prognostic system.

Conclusion:

we believe that the lack of any therapy of proven efficacy for paraquat poisoning makes it imperative to determine whether anti-neutrophil therapies work. In the absence of a properly validated prognostic marker to allow the use of nonrandomised studies, a large RCT using death as the primary outcome is required. This RCT should be used to prospectively test and validate the available prognostic methods so that future patients can be selected for this and other therapies on admission to hospital.

Introduction

Pesticide poisoning, particularly intentional self-poisoning, is a significant problem in many parts of the developing world.1 While organophosphorus pesticides are the most important cause of death and illness, other pesticides are important in particular regions.1 Paraquat dichloride is a bipyridyl compound that has been widely used as a non-selective contact herbicide since 1962.2-5 Ingestion of paraquat is a significant method of self-poisoning in parts of Asia, Pacific islands, and Caribbean.1,6

Paraquat is highly toxic if swallowed as the concentrated product.2-4 Ingestion of large amounts is considered to be uniformly fatal, resulting in death from multi-organ failure and cardiogenic shock within 1-4 days.4 After ingestion of smaller quantities, paraquat is specifically taken up into and accumulates in the lung.4 Subsequent redox cycling and free radical generation triggers a neutrophil-mediated inflammatory response in the lungs which initiates an irreversible fibrotic process that kills the majority of patients within several weeks.

Therapy has concentrated on reducing paraquat absorption from the GI tract and increasing its elimination. Unfortunately, all proposed interventions have been based on case reports or small case series and there is no substantiated clinical evidence that either reducing absorption with Fuller's earth, bentonite, and activated charcoal, or increasing elimination by forced diuresis, haemodialysis or standard haemofiltration have increased survival.3,4

However, Suzuki and colleagues7 have suggested that performing haemoperfusion for >10hrs increases survival time. A recent study from Koo and others8 also found that using continuous venovenous haemofiltration in addition to haemoperfusion reduced the proportion of patients dying from acute multiorgan failure, while increasing the proportion dying from respiratory failure. These studies add impetus to the search for therapies to prevent lung fibrosis since they suggest that it may be possible to reduce the paraquat load with extensive haemoperfusion and increase the number of patients potentially able to benefit from such therapies.

Since the principal biochemical mechanism for lung damage is initiated by oxygen free radicals produced by peroxidation, clinicians have tried a number of anti-oxidant treatments in the hope that they might interfere with the process.4,9 Unfortunately, none of the studied treatments, including controlled hypoxia, superoxide dismutase, vitamins C and E, N-acetylcysteine, desferroxamine, and nitrous oxide, have been proven to be effective.4,5,9,10

Immunosuppressive treatment for paraquat poisoning was first reported by Malone in 1971.11 This paper quickly stimulated further reports12,13 but there is currently no clear consensus about its efficacy.3,5,10 The first part of this paper reviews ten studies of immunosuppressive treatment for paraquat poisoning.

Seven of these studies used historical control patients, rather than control patients in a parallel group. Historical controls can only be accepted if there are clearly defined (statistical) predictors of prognosis which show that the two patient groups are comparable at baseline. A dramatic improvement in outcome in a sequentially treated group of patients might be regarded as sufficient proof of efficacy if such validated prognostic indicators exist. This is the basis, for example, on which N-acetylcysteine has been accepted as an effective antidote for early paracetamol poisoning without RCT evidence.14,15

In the second part of this paper, we report a systematic search for studies of prognosis in paraquat poisoning and assessment of their validity. If validated prognostic indicators exist, they may allow interpretation of the nonrandomised trials that use them. Alternatively, if none can be identified, evidence for efficacy of immunosuppression and other new therapies should only be accepted when the data come from RCTs.

Methods

We carried out a systematic search for clinical and prognostic studies by searching PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane databases (last checked 04/11/02), cross referencing from other articles, and contacting experts in the field to identify unpublished studies. All articles that were selected with the text words ‘paraquat’ together with ‘poisoning’ or ‘overdose’ were examined. Articles that could possibly be studies of immunosuppressive regimens or prognostic methods were retrieved to determine if this was the case. The web was also searched using www.google.com, www.yahoo.com,16 and the keywords: paraquat, cyclophosphamide, methylprednisolone, dexamethasone and prognosis (last checked 23/11/02). There were no constraints on quality of the studies. We included case reports if paraquat blood concentrations were determined.

Results

A search of medical databases for clinical studies of immunosuppression in paraquat poisoning revealed eight studies17-24 (table 1); a search for prognostic methods revealed 17 studies25-42 (tables 2 and 3). Searches of the internet revealed one further study of immunosuppression,43 a tenth study was presented at a toxicology meeting in 2003.44

Table 1.

Studies of immunosuppression in paraquat poisoning.

| Study | Location | Study group | Control group (form) |

PQ blood levels |

PQ urine levels |

Urine DN test |

Standard Rx | Immunosuppressive Rx | Patient survival |

Control survival |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Addo17 | Trinidad 7/83-1/84 |

20 |

ng Historical |

No | No | Yes | GL, FuE, K+, MDAC, MgS04, forced diuresis. |

Dexamethasone 8mg IV, q8h for 2 weeks, then 0.5mg PO, q8h for 2 more weeks. Cyclophosphamide 1.66mg/kg IV, q8h to a maximum of 4g over 4 weeks. |

75% | 20% |

| Addo18 | Trinidad 7/83- 12/84 |

72 | 61 Historical |

25/72 | No | Yes | GL, FuE, K+, MDAC, MgS04, forced diuresis. Vit B and C. |

Dexamethasone 8mg IV, q8h for 2 weeks, then 0.5mg PO, q8h for 2 more weeks. Cyclophosphamide 1.66mg/kg IV, q8h to a maximum of 4g over 4 weeks. |

72% | 32% |

| Perriens19 | Suriname 3/86-3/88 |

33 | 14 Historical |

26/47 | No | Yes | GL (<6hrs), Bent, MgS04, forced diuresis |

Dexamethasone 8mg IV, q8h for 2 weeks, then 0.5mg PO, q6h for 2 more weeks. Cyclophosphamide 1.66mg/kg IV, q8h to a maximum of 4g or 2 weeks. |

39% | 36% |

| Lin20 | Taiwan 7/92-6/94 |

29 (with dark or navy blue DN test) |

28 (with dark or navy blue DN test) Historical 7/89-6/91 |

No | No | Yes | GL, AC, HP for 8h. |

Methylprednisolone 1g IV, daily for 3 days. Cyclophosphamide 1g IV, daily for 2 days. |

41%* | 18%* |

| Vieira21 | Brasil, ng |

25 | 10 | No | ng | ng | HP or HD for 11/25. Details otherwise not given |

Dexamethasone 1.5mg/kg daily for d1-4, 1mg/kg daily for d5-7, then 24mg daily. Cyclophosphamide 15mg/kg IV d1, 10mg/kg d2, 7mg/kg d3-5, thereafter 5mg/kg daily, until total dose of 4g or leukocyte count <3000/mm3. |

72% | 0% |

| Lin22 | Taiwan 1/92- 12/97 |

56 (with dark or navy blue DN test) |

65 (with dark or navy blue DN test) Parallel, randomized |

No | No | Yes | GL, AC, 2 × HP for 8h. |

Methylprednisolone 1g IV, daily for 3 days. Dexamethasone 8mg IV, q8h for 2 weeks. Cyclophosphamide 15mg/kg IV, daily for 2 days. |

32%* | 18%* |

| Botella de Maglia23 | Spain ?/88-6/00 |

18 | 11 Historical 7/83-?/94 |

No | No | No | GL, FuE, AC, MgS04, forced diuresis. HP for 9/10 controls, 7/19 on steroids. Vit B+C with steroids. 1 control received dexamethasone. |

Dexamethasone 8mg IV, q8h for 2 weeks, then 0.5mg PO, q8h for 2 more weeks. Cyclophosphamide 1.66mg/kg IV q8h, to a maximum of 4g over 4 weeks. |

44% | 9% |

| Garcia43 | Venezuela 1990s |

10 |

ng Historical |

10/10 | No | Yes | Emesis, GL, FuE,, MgS04, forced diuresis. Vit C+E, NAC, HD for 5 days. |

Methylprednisolone 1g IV, daily for 3 days. Dexamethasone 8mg IV, q8h for 1 week. Cyclophosphamide 1g IV, daily for 2 days. |

80% | “0% in moderate to severe cases” |

| Chen24 | Taiwan, 1999 |

1 | na | Yes | No | Yes | GL, AC, Mg citrate. 2 × HP for 8h. |

Methylprednisolone 1g IV, daily for 3 days. Cyclophosphamide 15mg/kg IV, daily for 2 days. Then: Dexamethasone 5mg IV, q8h for 30days. Second course of methylprednisolone and cyclophosphamide as above. |

survived | na |

| Chomchai44 | Thailand, 2001-2 |

4 | na | No | No | No | FE, Vit C 6g/day | Dexamethasone 10mg q8h IV for 14d. Cyclophosphamide 1.7mg/kg IV q8h for 14d. |

100% | na |

Analysis by the present authors according to intention-to-treat.

Key: AC – activated charcoal; Bent – bentonite; DN – dithionite test; FuE – Fuller's earth; GL – gastric lavage; HD – haemodialysis; HP – haemoperfusion; IV – intravenous; MDAC – multiple dose activated charcoal; NA - not applicable; NAC – N-acetylcysteine; NG - not given; PO – by mouth; PQ – paraquat.

Table 2.

Studies of prognostic markers in paraquat poisoning.

| Study | Location, Years |

Patients | Dx | Blood level |

Urine Level |

Treatment | Survival | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incl | Excl |

Gastric lavage |

Bowel absorbent |

Forced diuresis |

Haemodialysis | Haemoperfusion | Steriods | Included (Overall) |

||||||

| 1 | Wright25 | UK ng |

16 | 0 | Hx, Urine pq assay |

No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (25%) |

No | Yes (19%) |

No | 56% |

| 2 | Proudfoot26 | UK, ng |

71 <35h |

8 >35h |

Hx, Blood pq assay |

Yes plasma |

No | ng | ng | ng | ng | ng | ng | 66% (65%) |

| 3 | Hart27 | UK, ng |

219 | 0 | Hx, Blood pq assay |

Yes plasma |

No | ng | ng | Yes (18%) |

Yes (13%) |

Yes (21%) |

No | 50% |

| 4A | Scherrmann28 | France ng |

30 >24 h |

0 | Hx, Blood pq assay |

Yes plasma |

No | ng | ng | ng | ng | ng | ng | 30% |

| 4B | Scherrmann28 | France ng |

53 <24 h |

0 | Hx, Urine pq assay |

ng | Yes | ng | ng | ng | ng | ng | ng | 36% |

| 5 | Fock29 | Singapore, 1976-84 |

14 | 13 (no Ur pq assay) |

Hx, Body fluid assay |

Yes ?p/s |

Yes | Yes (100%) |

bentonite (100%) |

Yes (100%) |

No | No | Yes (100%) |

21% (22%) |

| 6 | Sawada30 | Japan, 1985-87 |

30 | 0 | Hx Blood pq assay |

Yes serum |

No | ng * | ng | ng | ng | ng | ng | 33% |

| 7 | Suzuki31 | Japan, ng |

51 | 0 | Hx Urine pq |

Yes plasma |

Yes (dn) |

Yes | AlSiO3 | Yes | Yes (45%) |

Yes (90%) |

Yes | 16% |

| 8 | Yamaguchi32 | Japan, 1981-87 |

65 | 95 | Hx Urine pq |

No | Yes (dn) |

Yes (ng) |

AC (ng) |

Yes (ng) |

Yes (ng) |

Yes (ng) |

No | 26% (ng) |

| 9 | Kaojarern33 | Thailand, 1983-88 |

24 | 0 | Hx & Ex, or pq assay |

Yes | Yes (dn) |

No | FuE | Yes | Yes (38%) |

Yes (4%) |

No | 29% |

| 10 | Yamashita34 | Japan Late 80s |

18 | 0 | Hx Blood pq Assay |

Yes serum |

Yes | NG | NG | NG | NG | NG | NG | 33% |

| 11 | Ragoucy-Sengler35 | Guadeloupe 1987-91 |

25 | 0 | Hx Blood pq assay |

Yes plasma |

No | Yes (ng) |

FuE (ng) |

Yes (ng) |

No | No | Yes (ng) |

44% |

| 12 | Ragoucy-Sengler36 | Guadeloupe early 1990s |

18 | 0 | Hx Blood pq assay |

Yes plasma |

No | ng | ng | ng | ng | ng | ng | 33% |

| 13 | Ikebuchi37,38 | Japan, Australia, ng |

128 | 0 | Hx Blood pq assay |

Yes plasma |

No | ng | ng | ng | ng | ng | ng | 16% |

| 14A | Scherrmann39 | France, Japan ng |

49 | 3 | Hx, Blood pq assay |

Yes plasma |

No | ng | ng | ng | ng | ng | ng | 27% |

| 14B | Scherrmann39 | France, Japan ng |

75 | 0 | Hx, Urine pq assay |

? | Yes | ng | ng | ng | ng | ng | ng | 32% |

| 15 | L'heureux40 | Worldwide review until late 1990s |

89 | 0 | Hx Blood pq assay |

Yes | No | ng | ng | ng | ng | ng | ng | 28% |

| 16 | Jones41 | Worldwide review, until late 1990s |

375 | Hx Blood pq assay |

Yes | No | ng | ng | ng | ng | ng | ng | 36% | |

| 17 | Hong42 | Korea 1999 |

147 | 0 | Hx +/− Urine pq** |

No | Yes (dn) |

Yes (<6h) |

FuE (<12h) |

No | No | Yes (60%) |

No | 56% |

Urine dipstick was positive in 93 of 147 (63%) patients from whom urine was taken in the ED. Although blood levels were said to have been taken, no further evidence confirming that the other 40% had proven paraquat poisoning was presented. The high survival rate may reflect low level poisoning or inclusion of patients who had not ingested paraquat

Table 3.

Proposed prognostic formula or marker from each study.

| Study | Prognostic formula for survival | Constraints | Validated by authors? (No of new patients) | Result (spec/sens) | Tested by others? | Reference papers (# patients) | Sensitivity and specificity of proposed cutpoint for prediction of death (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wright25 | PQ excretion >1mg/hr >8h post-ingestion predicts death | Urine PQ assay required | No | na | No | na | na |

| Proudfoot26 | Survivors have plasma paraquat concentrations not exceeding 2.0, 0.6, 0.3, 0.16, and 0.1 μg/ml at 4, 6, 10, 16, and 24h post-ingestion (figure 1A) | Applicable up to 24h. PQ plasma assay required | No | na | Yes | Bismuth,50 17 patients (12 dead) Ragoucy-Sengler35 25 patients (14 dead) |

Sensitivity 100% (74-100%) Specificity 100% (48-100%) Sensitivity 100% (77-100%) Specificity 73% (39-94%) |

| Hart27 | Graph of plasma concentration on admission vs. time since ingestion generated with contour map lines denoting equal probability of survival (figure 1B) | Applicable up to 28h. PQ plasma assay required | No | na | Yes | Perriens19 26 (19 dead) |

Prediction <65%: Sensitivity 100% (82-100%) Specificity 100% (59-100%) |

| Scherrmann28,39 | Survivors have plasma paraquat levels less than ‘c’ μg/L at time point t (hrs), using the following equation c = 103/ (0.471 t − 1.302) |

Applicable after 24h. PQ plasma assay required | No | na | No | na | na |

| Scherrmann28,39 | Urine PQ <1mg/ml within the first 24h predicts survival | Urine PQ assay required | No | na | No | na | na |

| Fock29 | Urine PQ <0.8mg/ml within 8h predicts survival | Urine PQ assay required | No | na | No | na | na |

| Sawada30 | SIPP <10 predicts survival; SIPP 10-50, death from lung fibrosis; SIPP >50, death from circulatory failure SIPP (severity index of paraquat poisoning) = time to treatment (hrs) × serum PQ concentration (?mg/L°) |

Applicable up to 200h. Plasma assay required | No | na | No | na | na |

| Suzuki31 | Respiratory index (RI) <1.5 predicts survival RI* = A-aDO2/PO2 A-aDO2 = 713 × FiO2 − PCO2 [FiO2 + (1 − FiO2)/0.8] − PO2 |

Requires blood gas assay | No | na | No | na | na |

| Yamaguchi32 | Patients with: Eq1 >(1500 − 399 × LogT) have a 90% probability of survival, and Eq1 <(930 − 399 × LogT) have a 3% probability of survival, Patients with a value in-between have a 38% probability of survival. LogT = log of time to admission from PQ ingestion. Eq1 = [K+] × [HCO3−] / [Creatinine] (All values in mEq L−1) |

Requires basic biochemical assays | No | na | Yes | Ragoucy-Sengler35 25 patients (14 dead) |

Sensitivity 100% (77-100%) Specificity 73% (39-94%) |

| Kaojarern33 | In survivors, the following formula is positive: 0.027 × age (yrs) + 0.022 × ingested volume (ml) + 0.0002 × WBC (cells/mm3) |

WBC required. Estimate of volume is unreliable | Yes 9 patients |

100% 100% |

No | na | na |

| Yamashita34 | U-SIPP (urine severity index of paraquat poisoning) = urine PQ concentration (μg/ml) × time in hrs between ingestion and start of intensive therapy. With creatinine clearance >20ml/min, patients with U-SIPP >1250 die from circulatory failure, those with U-SIPP 250-1250 die from lung fibrosis, and those with U-SIPP <250 survive |

Urine PQ assay required | No | na | No | na | na |

| Ragoucy- Sengler35 |

Chronic alcoholic Caribbean men with gGT >40 IU/L and mcv >100fl have an improved probability of survival. Not quantitated. | Requires Hx plus basic bioch/haem assays | No | na | No | na | na |

| Ragoucy- Sengler36 |

dCreat/dt <3.0 predicts survival. dCreat/dt = [Creat (T5) − Creat (T0)] /5 (where T5 is five hours after T0 which can be at any time after the poisoning; Cr in μol/L) |

Time post-ingestion is not required. Requires only basic biochemical assays | No | na | No | na | na |

| Ikebuchi37,38 | D score >0.1 predicts survival, D <−0.1 predicts death. D = 1.3114 − 0.1617lnT − 0.5408ln [ln (C × 1000)] where: T = time from ingestion (h) C = plasma paraquat ingestion (μg/ml) |

pq plasma assay required | Yes 128 patients |

? | No | na | na |

| L'heureux40 | Survivors have a blood PQ level below a line linking 2 μg/ml at ∼13h and 0.7μg/ml at ∼75h on a semi-log plot. | Applicable up to 100h. pq blood assay required. |

No | na | No | na | na |

| Jones41 | The probability of survival = exp(logit) / [1 + exp(logit)] logit = 0.58 − [2.33 × log (plasma paraquat)] − [1.15 × log (h since ingestion)] pq concentration in μg/ml (see figure 2A for derived 90% survival curve) |

Applicable up to 200h. pq plasma assay required |

No | na | No | na | na |

| Hong42 | “subjects with liver or renal dysfunction or metabolic acidosis had significant risks of fatality” |

Units were not given in the paper but are presumed to be mg/L from earlier work.

Studies of immunosuppression for paraquat induced lung fibrosis

One study was a randomised clinical trial; seven other studies used historical control groups while two reported case series of one and four patients, respectively. Details of the studies including selection criteria for patients and controls are summarised in Table 1 and elaborated below.

The RCT

In 1999, Lin and colleagues published a randomised controlled trial of pulse methylprednisolone and cyclophosphamide in paraquat poisoning.22 Their paper reported a highly significant improvement in survival in moderate-to-severely poisoned patients randomised to pulse therapy: from 43% (12/28) to 72% (18/22; P=0.008).22

The conclusions are, however, complicated by their exclusion of patients dying within seven days - patients whom they defined as having ‘fulminant’ rather than ‘moderate-to-severe’ poisoning. This demarcation could only be made retrospectively at seven days when survivors were identified. Their paper did not therefore present an intention-to-treat analysis but one in which 50% of patients were retrospectively excluded because of death from ‘fulminant’ poisoning. Unless it is possible to be certain that the immunosuppressive drugs themselves did not influence the outcome of those patients dying within seven days this exclusion is not justified . Reanalysis on an intention-to-treat basis shows an improvement which was not significant at the 0.05 statistical level: from 18% (12/65) to 32% (18/56; P=0.095).45 This means that the study points towards a benefit of immunosuppressive treatment but that it was insufficiently powered to detect the effect statistically.

The study is described as a prospective clinical trial with patients randomised to usual or immunosuppressive treatment.22 Due to brevity of reporting, however, it is difficult to determine how the trial was actually performed.46,47 In addition, the start of patient recruitment to this trial (Jan 1992) predates recruitment of patients to the treatment cohort of their non-randomised study (July 1992).20 Although not stated in the papers, these studies were performed in two different hospitals of the same group in Taipei (J Lin, personal communication).

The authors concluded both this paper and a subsequent letter to the journal with the statement that further double-blinded controlled studies are required to determine the efficacy and limitations of pulse therapy.22,48

Non-randomised studies

Study 1

Addo and colleagues reported the results of treating 20 patients with dexamethasone and cyclophosphamide in 1984.17 Compared to their previous 20% survival rate, they reported a much improved rate of 75%. All 20 patients had raised serum creatinine and bilirubin concentrations, suggesting significant exposure. However, exposure was only quantified from the volume of paraquat stated to have been ingested and not via plasma paraquat assays.

Study 2

The same authors subsequently reported their experience with a further 52 patients, presenting 72 patients in all.18 Again, they reported a much higher survival rate, of 72% compared to 32%, in patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy compared to historical controls treated with standard therapy.

In response to the criticisms faced by their first study, they retrospectively measured serum paraquat concentrations in 25 patients. Amongst these patients, the survival rate was 52% (13/25) but 6 had no detectable serum paraquat (suggesting minimal exposure).49 Therefore, of the 19 patients with proven paraquat exposure, only seven survived (37%) and four of these had blood concentrations which predicted a better than even chance of survival according to the Proudfoot nomogram.

Study 3

Perriens and colleagues subsequently reported their experience of using the Addo regimen of immunosuppression in Suriname.19 They treated 14 patients with usual therapy from March until October 1986 when dexamethasone and cyclophosphamide became available. 33 patients were subsequently treated with Addo's regimen. They found no difference between the two groups in terms of total mortality (20/33 vs. 9/14; 61% vs. 64%), death from lung fibrosis (6/33 vs. 2/14; 18% vs. 14%), and renal failure (24/33 vs. 10/14; 73% vs. 71%).19

Serum paraquat concentrations were assayed in 26 consecutive patients: 14 of the usual therapy group and 12 of the immunosuppressive group. Using the nomogram of Hart,27 they reported that all patients who had a predicted chance of survival less than 65% died, irrespective of the treatment given (9/14 receiving usual therapy, 10/12 receiving immunosuppression). All patients with a predicted survival greater than 65% survived.

Study 4

In 1996, Lin and colleagues reported a study of pulse immunosuppression in 87 patients seen in their hospital between July 1989 and June 1991 (control patients) and between July 1992 and June 1994 (patients treated with immunosuppression).20 They reported a better outcome with immunosuppressive therapy: 12/16 (75%) ‘moderate-to-severely’ poisoned patients surviving compared to 5/17 (29%) historical controls. This study was also complicated by their exclusion of patients dying from ‘fulminant’ poisoning.

Only patients with ‘navy blue’ or ‘dark blue’ urine dithionite tests were considered as moderate-to-severely poisoned and therefore given immunosuppression. This practice excluded mildly poisoned patients with a hypothetically good prognosis. Analysing only patients with navy or dark blue urine dithionite tests gives survival rates of 41% (12/29) and 18% (5/28) in the treated and control groups, respectively.

Study 5

A study of forty patients from Campinas, Brasil, has been reported in abstract format only.21 Five patients had mild poisoning and were not further studied. Eighteen of 25 patients receiving a reducing course of cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone survived; all ten patients who did not receive immunosuppressive therapy died. Unfortunately, the abstract did not present methodology; most importantly, the method used to determine allocation to immunosuppressive therapy or standard therapy was not stated. The use of paraquat assays in blood or urine, or the dithionite test, was also not detailed.

Study 6

A series of 29 patients treated over seventeen years in Valencia, Spain, was reported in 2000.23 The clinicians started using immunosuppressive drugs in 1988, initially adding them to haemoperfusion, and then stopping haemoperfusion and relying on immunosuppression alone. They reported a marked improvement with immunosuppressive therapy: an increase in survival from 9% to 44%, in particular in patients reporting the ingestion of <45mls of 20% concentrate.

However, blood paraquat concentrations were not obtained and the degree of exposure therefore not known. Of the 22 patients who developed acute renal failure (defined as urine output <400ml/day and/or serum creatinine >133μmol/L), suggesting significant exposure, only 3 (14%) survived. Similarly, 17 of 18 patients with acute respiratory failure (PaO2 <60mmHg in room air) died.

Study 7

A series of ten ‘moderately to severely poisoned’ patients treated with immunosuppression was reported from Ciudad Bolívar, Venezuela.43 Compared to the hospital's “usual 100% fatality rate” in such patients, the authors reported survival in 8 of 10 patients. They concluded that “methylprednisolone and cyclophosphamide are effective in preventing acute respiratory failure, … and reducing mortality”.

Paraquat concentrations were available but presented as a mean only, with no indication of time post ingestion for each individual patient's paraquat level. The mean was stated to be 3.58+/−0.31, with units ‘pu/ml’ in the text and ‘pg/ml’ in the abstract’. These values seem low: Proudfoot's paper used a value of 2mg/l (2μg/ml) as a cut off for survival at 4hrs.26 These values appear to be 106-fold lower.

Other features suggest that most patients were not significantly poisoned: leucocyte counts ranged from 4.1 to 16.7 (less than all 72 patients in Addo's study18), only four developed acute renal failure (2 deaths), three of four had normal upper GI endoscopy,50 and three of three had completely normal spirometry.

Study 8

The Taiwanese group recently reported a single patient who received two courses of pulse immunosuppression for paraquat poisoning.24 The patient had a blood paraquat concentration of 3.36μg/ml 10h after ingestion (suggestive of poor prognosis by all nomograms) and developed renal failure requiring haemodialysis. Interstitial lung infiltration was noted on X-ray, and he became hypoxic (nadir PaO2 of 66.6mmHg, 8.9Pa, on day 30). The lung fibrosis progressed despite treatment with a course of pulse immunosuppression and 25 days of dexamethasone (see table 1 for dosage details). However, a 2nd course of pulse immunosuppression started on day 30 coincided with clinical improvement and he was discharged from hospital on day 41.

Study 9

Chomchai and Chomchai have reported in abstract form 4 Thai patients treated with dexamethasone and cyclophosphamide.44 Although blood paraquat levels were not assayed, they were considered moderately-to-severely poisoned on the basis of a history of ingesting 1g or 20mg/kg paraquat. Three of four developed both renal failure and hepatitis suggesting significant exposure; however, none developed pulmonary complications and all four survived.

Prognosis of acute paraquat poisoning

The search revealed 18 studies using patient investigations (tables 2 and 3). Seven and four studies used plasma or urine paraquat concentrations, respectively, for prediction of prognosis; one study used arterial blood gas analysis, and four used fairly simple biochemical and/or haematological assays. One study reported that Caribbean men with a history of chronic alcohol use and raised γGT and MCV had a good prognosis but was unable to quantify it.35 A recent study reported an association between renal and liver failure and a metabolic acidosis with poor outcome but offered no method for distinguishing people who would survive from those who wouldn't.42 The treatment given to patients varied both within studies and across studies. Most studies included all eligible patients.

None of these systems have been validated. Only one study tested the proposed method for survival prediction and this was with nine patients. Three prognostic systems were tested by other clinicians but they again used only small numbers of independent patients (maximum of 79; see table 3). The largest study, that of Suzuki and colleagues51 compared the accuracy of three different prognostic systems: Proudfoot's26 and Scherrmann's28 nomograms and the Severity Index of Paraquat Poisoning (SIPP) of Sawada and colleagues.30 Although they tested the systems with 79 independent patients, the results are confused by their incorporation of 144 patients from the original papers into the analyses. Since the systems were developed using data from these patients, they cannot be used again to test the system.

Discussion

We were unable to find any study that definitively established the role of immunosuppression in paraquat poisoning. We were also unable to find any properly validated prognostic method that would allow clinicians i) to use historical controls in studies of new treatments and ii) to predict which patients will die from lung fibrosis, rather than acute multi-organ failure, and therefore possibly benefit from immunosuppressive therapy.

Immunosuppression and lung fibrosis

We found ten studies assessing the effect of immunosuppressive therapy on outcome in paraquat poisoning.

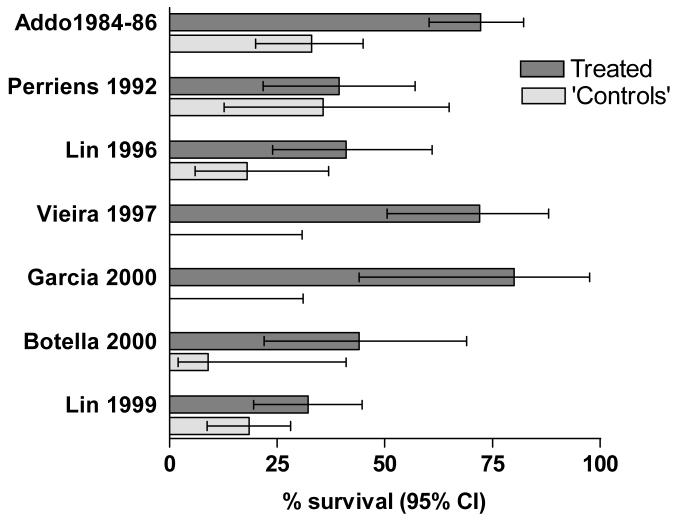

All but two studies reporting more than one patient used historical controls. Using such controls for controlled trials of new interventions, rather than controls treated in parallel, is associated with inflation of evidence for benefit.46,52-54 These studies therefore cannot be considered to provide good evidence of benefit or harm from immunosuppression. A feature of these trials is the great variation in survival rates between different studies (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Survival rates and 95% confidence intervals for the seven studies using either parallel or historical controls (since Addo 198618 includes the patients reported in Addo 1984,17 the latter is not presented alone). Analysis by the present authors according to intention to treat.

RCTs are the highest rated form of study for intervention trials. One study was described as a RCT and it reported significant benefit for immunosuppression. Unfortunately, little methodology (as requested by the CONSORT statement46,47) was given in the published paper. It is consequently not possible to assess many elements of trial design and analysis and, in particular, allocation concealment.53

The RCT was not analysed on an intention-to-treat basis. The paper's analysis thus misses the possibility that the treatment itself may have caused harm (including death) in that arm. An ITT analysis, while suggesting some benefit from immunosuppression, does not confirm benefit to the 0.05 level.45 Despite these problems, some commentators have stated the treatment should be widely used.55,56 We believe this conclusion to be premature and that further RCTs are required (see below).

Future studies of paraquat poisoning using historical controls may be of some value if it is possible to demonstrate that both groups of patients had a similar degree of exposure to paraquat and similar prognoses, in particular their risk of dying from paraquat-induced lung fibrosis. This requires validated prognostic methods.

The single case presented by Chen and colleagues is well characterised and does suggest that high-dose pulse immunosuppression may be of benefit. Of note, this patient required two courses of immunosuppression 4 weeks apart, in contrast with their RCT in which patients received only one course.

Prognostic methods for paraquat poisoning

We found 18 studies that reported a link between the result of investigations and outcome. Fifteen of these studies proposed a nomogram or formula for predicting outcome. However, just one was tested with new patients by the same authors and only three appear to have been tested by other researchers. None have been prospectively validated in a large cohort.

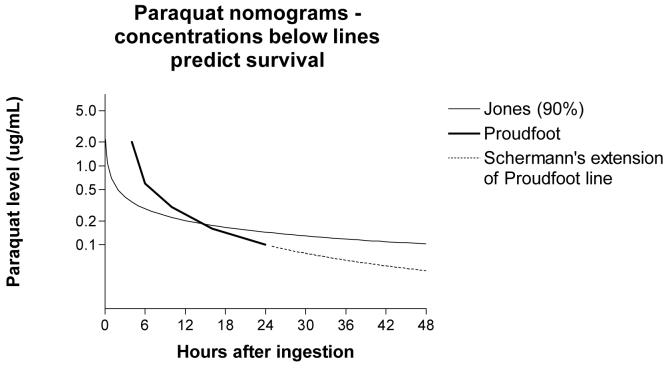

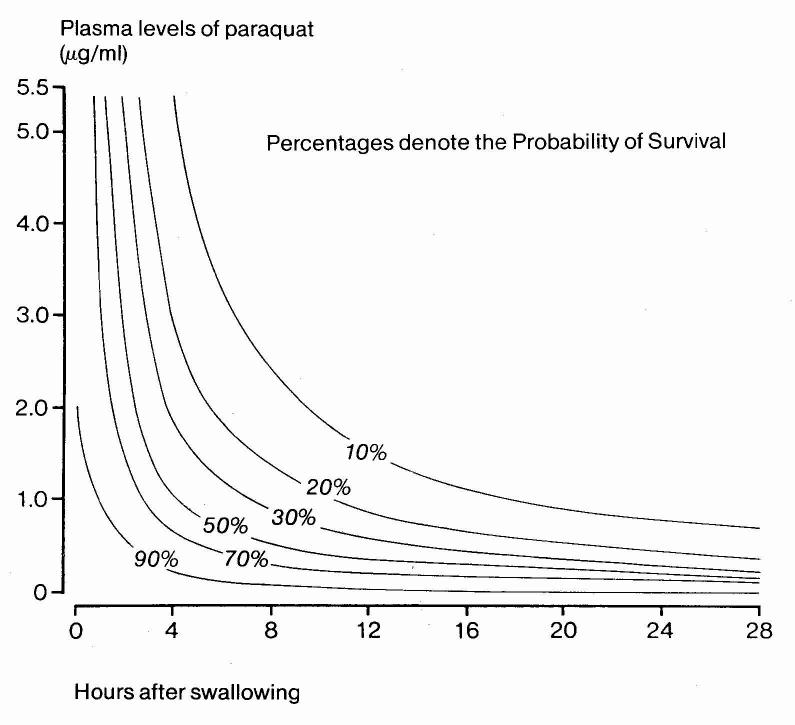

The plasma paraquat concentration seems likely to be the most useful marker of exposure and severity (figures 2 and 3).39 A major constraint of this method is the inability of many hospitals in the developing world, where most patients present, to do the assay. Even where the necessary analytical facilities exist, most currently available methods require experience and rigorous quality control to provide reliable results. A properly validated, affordable and robust bedside test of paraquat concentration could make a significant difference.

Figure 2.

Nomograms for plasma paraquat concentrations proposed by Proudfoot,26 Scherrmann,28 and Jones41 (2A) and Hart27 (2B). In 2A, concentrations below lines predict survival. In 2B, lines link concentrations of equal probability of death.

In the absence of such an assay, the urine dithionite test is often used to estimate the level of exposure. Its validity is questionable since urine paraquat concentration will depend on the individual's renal function – young people with excellent renal function will initially excrete more paraquat than someone with poor renal function. Patients with poor renal function will have higher urine concentrations at later timepoints. Urine production will also decrease as the poisoning progresses, since paraquat causes renal failure.4,28 Such variation may push the urine paraquat level above or below the threshold for detection.

Scherrmann's later and larger study of 75 patients with this assay found that 3 of 21 patients (14%) with a negative or pale blue test result died while 6 of 54 (11%) of patients with a navy or dark blue test survived.39 Similarly, Hwang and colleagues study found that 5/59 patients (8%) with a negative dithionite assay died while at least 13/75 patients (17%) with a ‘++ to ++++’ positive result survived.57 The performance of the dithionite test in predicting an adverse prognosis is therefore not sufficiently accurate as to validate the use of historical controls. However, the performance of this simple urine assay may be as good as any single cut off point of blood concentration in terms of the positive likelihood ratio and it may be useful as an entry criteria for RCTs.

Yamashita published a paper in Japanese in 1989 that reported a Severity Index using urine paraquat levels.34 He controlled for renal function by including only patients with a creatinine clearance of >20ml/min. His formula predicted 6/6 survivors; unfortunately, he did not validate it with other patients and no-one else appears to have used it.

Other methods of prognosis prediction have used the results of biochemical tests such as potassium, bicarbonate and creatinine concentrations. However, most require knowledge of time of ingestion and/or quantity ingested, both often difficult to determine, particularly in those who co-ingest alcohol. One of the attractions of Ragoucy-Sengler's proposed system,36 based on changes in creatinine concentration over five hours, is that it is independent of both variables.

Future studies

We believe that a RCT, sufficiently large as to find a 10% absolute difference in all cause mortality, is urgently required to establish whether high dose pulse immunosuppression as used by Lin and colleagues is effective in preventing paraquat-induced lung fibrosis. In Lin's RCT, overall survival in control patients (with exposure shown by a navy or dark blue dithionite test) was 18% (12/65) compared with 32% (18/56) in the treatment arm. In order to be able to detect whether either regimen increases survival from 18% to 28%, with a significance level (alpha) of 5% and a power of 80%, a minimum of 295 patients with significant poisoning (navy or dark blue urine dithionite test) would have to be recruited to each arm of the trial (590 patients in total).

It will be important in this study to also take enough biochemical data (blood and urine paraquat levels, baseline biochemistry, and possibly arterial blood gas, at study entry and five hours) to prospectively test a number of the proposed prognostic methods.

Acknowledgements

We thank Lewis Smith, Kyu-Yoon Hwang, J-L Lin, Andrew Dawson, Alison Jones, and the QJM reviewer for their comments on this paper and /or their responses to our questions concerning their studies. ME is a Wellcome Trust Career Development Fellow in Tropical Clinical Pharmacology; funded by grant GR063560MA.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

MW is an employee of Syngenta, a manufacturer of paraquat. ME and NB have accepted hospitality (meals, transport) from MW to the sum of around 50USD and 20USD, respectively. ME, MW and NB are now starting a RCT in Sri Lanka, funded by Syngenta, that will address the question of benefit of immunosuppression in the treatment of paraquat poisoning.

References

- 1.Eddleston M. Patterns and problems of deliberate self-poisoning in the developing world. Q J Med. 2000;93:715–31. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/93.11.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . Environmental health criteria # 39. Paraquat and diquat. Geneva: IPCS Inchem, WHO; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization . Poison information monograph 399. Paraquat. Geneva: IPCS Inchem, WHO; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lock EA, Wilks MF. Handbook of pesticide toxicology. 2 edn. San Diego: Academic Press; 2001. Paraquat. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reigart JR, Roberts JR. Recognition and management of pesticide poisonings. Washington DC: Office of Pesticide Programs, Environmental Protection Agency; 1999. Paraquat and diquat; pp. 108–17. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malpica Rivero JA, Pila Perez R, Pila Pelaez R, Guerra Rodriguez C, Meifas Rodriguez I. Intoxicacion por gramoxone. Nuestra experiencia. Mapfre Medicina. 2001;12:122–6. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suzuki K, Takasu N, Okabe T, Ishimatsu S, Ueda A, Tanaka S, Fukuda A, Arita S, Kohama A. Effect of aggressive haemoperfusion on the clinical course of patients with paraquat poisoning. Hum Exp Toxicol. 1993;12:323–7. doi: 10.1177/096032719301200411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koo J-R, Kim J-C, Yoon J-W, Kim G-H, Jeon R-W, Kim H-K, Chae DW, Noh J-W. Failure of continuous venovenous hemofiltration to prevent death in paraquat poisoning. Am J Kidney Diseases. 2002;39:55–9. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.29880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suntres ZE. Role of antioxidants in paraquat toxicity. Toxicology. 2002;180:65–77. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(02)00382-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Newstead CG. Cyclophosphamide treatment of paraquat poisoning. Thorax. 1996;51:659–60. doi: 10.1136/thx.51.7.659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malone JDG, Carmody M, Keogh B, O'Dwyer WF. Paraquat poisoning - a review of nineteen cases. J Irish Med Assoc. 1971;64:59–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grabensee B. Clinical treatment of paraquat (dimethylbipyridinium dichloride) poisoning. Pneumonologie. 1974;150:173–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02179316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fenelly JJ, Fitzgerald MX, Fitzgerald O. Recovery from severe paraquat poisoning following forced diuresis and immunosuppressive therapy. J Irish Med Assoc. 1971;64:69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prescott LF, Illingworth RN, Critchley JAJH, Stewart MJ, Adam RD, Proudfoot AT. Intravenous N-acetylcysteine: the treatment of choice for paracetamol poisoning. BMJ. 1979;ii:1097–100. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6198.1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vale JA, Proudfoot AT. Paracetamol (acetaminophen) poisoning. Lancet. 1995;346:547–52. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91385-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wukovitz LD. Using internet search engines and library catalogs to locate toxicology information. Toxicology. 2001;157:121–39. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(00)00343-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Addo E, Ramdial S, Poon-King T. High dosage cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone treatment of paraquat poisoning with 75% survival. West Indian Med J. 1984;33:220–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Addo E, Poon-King T. Leucocyte suppression in treatment of 72 patients with paraquat poisoning. Lancet. 1986;i:1117–20. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)91836-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perriens JH, Benimadho S, Kiauw IL, Wisse J, Chee H. High dose cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone in paraquat poisoning: a prospective study. Hum Exp Toxicol. 1992;11:129–34. doi: 10.1177/096032719201100212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin JL, Wei MC, Liu YC. Pulse therapy with cyclophosphamide and methylprednisolone in patients with moderate to severe paraquat poisoning: a preliminary report. Thorax. 1996;51:661–3. doi: 10.1136/thx.51.7.661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vieira RJ, Zambrone FA, Madureira PR, Bucaretchi F. Treatment of paraquat poisoning using cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone. J. Toxicol. Clin. Toxicol. 1997;35:515–6. Ref Type: Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin JL, Leu ML, Liu YC, Chen GH. A prospective clinical trial of pulse therapy with glucocorticoid and cyclophosphamide in moderate to severe paraquat-poisoned patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:357–60. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.2.9803089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Botella de Maglia J, Belenguer Tarin JE. Intoxicacion por paraquat. Estudio de 29 casos y evaluacion del tratamiento con la ‘pauta caribena’. Med Clin (Barc) 2000;115:530–3. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7753(00)71615-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen G-H, Lin JL, Huang Y-K. Combined methylprednisolone and dexamethasone therapy for paraquat poisoning. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:2584–7. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200211000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wright N, Yeoman WB, Hale KA. Assessment of severity of paraquat poisoning. BMJ. 1978;ii:396. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6134.396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Proudfoot AT, Stewart MS, Levitt T, Widdop B. Paraquat poisoning: significance of plasma paraquat concentrations. Lancet. 1979;ii:330–2. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(79)90345-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hart TB, Nevitt A, Whitehead A. A new statistical approach to the prognostic significance of plasma paraquat concentrations. Lancet. 1984;ii:1222–3. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)92784-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scherrmann JM, Houze P, Bismuth C, Bourdon R. Prognostic value of plasma and urine paraquat concentration. Human Toxicol. 1987;6:91–3. doi: 10.1177/096032718700600116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fock KM. Clinical features and prognosis of paraquat poisoning: a review of 27 cases. Singapore Med J. 1987;28:53–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sawada Y, Yamamoto I, Hirokane T, Nagai Y, Satoh Y, Ueyama M. Severity index of paraquat poisoning. Lancet. 1988;i:1333. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)92143-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suzuki K, Takasu N, Arita S, Maenosono A, Ishimatsu S, Nishina N, Tanaka S, Kohama A. A new method for predicting the outcome and survival period in paraquat poisoning. Human Toxicol. 1989;8:33–8. doi: 10.1177/096032718900800106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamaguchi H, Sato S, Watanabe S, Naito H. Pre-embarkment prognostication for acute paraquat poisoning. Hum Exp Toxicol. 1990;9:381–4. doi: 10.1177/096032719000900604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaojarern S, Ongphiphadhanakul B. Predicting outcomes in paraquat poisonings. Vet Hum Toxicol. 1991;33:115–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamashita J. Clinical studies on paraquat poisoning: prognosis and severity index of paraquat poisoning using the urine levels. Nippon Hinyokika Gakkai Zasshi. 1989;80:875–83. doi: 10.5980/jpnjurol1989.80.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ragoucy-Sengler C, Pileire B, Daijardin JB. Survival from severe paraquat intoxication in heavy drinkers [letter] Lancet. 1991;338:1461. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92762-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ragoucy-Sengler C, Pileire B. A biological index to predict patient outcome in paraquat poisoning. Hum Exp Toxicol. 1996;15:265–8. doi: 10.1177/096032719601500315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ikebuchi J. Evaluation of paraquat concentration in paraquat poisoning. Arch Toxicol. 1987;60:304–10. doi: 10.1007/BF01234670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ikebuchi J, Proudfoot AT, Matsubara K, Hampson EOGM, Tomita M, Suzuki K, Fuke C, Ijiri I, Tsunerari T, Yuasa I, Okada K. Toxicological index of paraquat: a new strategy for assessment of severity of paraquat poisoning in 128 patients. Forensic Sci Int. 1993;59:85–7. doi: 10.1016/0379-0738(93)90147-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scherrmann JM. Paraquat poisoning. New York: Dekker; 1995. Analytical procedures and predictive value of late plasma and urine paraquat concentrations; pp. 285–96. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lheureux P, Ekwall B. Paraquat. (The monographs. No. 25).Time-related lethal blood concentrations from acute human poisoning of chemicals. 1997;(Part 2) Ref Type: Serial (Book,Monograph) [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jones AL, Elton R, Flanagan R. Multiple logistic regression analysis of plasma paraquat concentrations as a predictor of outcome in 375 cases of paraquat poisoning. Q J Med. 1999;92:573–8. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/92.10.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hong S-Y, Yang D-H, Hwang K-Y. Associations between laboratory parameters and outcome of paraquat poisoning. Toxicol Lett. 2000;118:53–9. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(00)00264-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Garcia J, Frontado C, Tilac C, Rendon C, Brewster F, Gonzalez A, Nazzoure J, Flores L, Guipe S, Vargas S, Medina R, Pernalete N. Intoxicacion moderada a severa por paraquat tratada con esteroides e inmunosupresores. Datos preliminares. Ann Intern (Caracas) 2000;16 ? [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chomchai S, Chomchai C. Treatment of moderate to severe paraquat poisoning with dexamethasone/cyclophosphamide combination: a case series from the toxicology consultation service at Siriraj Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand. J.Toxicol.Clin.Toxicol. 2003;41:520–1. Ref Type: Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Buckley NA. Pulse corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide in paraquat poisoning. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:585. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.2.16310a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Altman DG, Schulz KF, Moher D, Egger M, Davidoff F, Elbourne D, Gotzsche PC, Lang T. The revised CONSORT statement for reporting randomized trials: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:663–94. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-8-200104170-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG, the CONSORT Group The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomised trials. Lancet. 2001;357:1191–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lin JL. Pulse corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide in paraquat poisoning. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:585. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.2.16310a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vale JA, Meredith TJ, Buckley BM. Paraquat poisoning [letter] Lancet. 1986;i:1439. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)91579-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bismuth C, Garnier R, Dally S, Fournier PE. Prognosis and treatment of paraquat poisoning: a review of 28 cases. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1982;19:461–74. doi: 10.3109/15563658208992501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Suzuki K, Takasu N, Arita S, Ueda A, Okabe T, Ishimatsu S. Evaluation of severity indexes of patients with paraquat poisoning. Hum Exp Toxicol. 1991;10:21–3. doi: 10.1177/096032719101000104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Hayes RJ, Altman DG. Empirical evidence of bias: dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA. 1995;273:408–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.273.5.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Allocation concealment in randomised trials: defending against deciphering. Lancet. 2002;359:614–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07750-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kunz R, Oxman AD. The unpredictability paradox: review of empirical comparisons of randomised and nonrandomised clinical trials. BMJ. 1998;317:1185–90. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7167.1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Duenas Laita A, Nogue S. Erratum: cyclophosphamide in paraquat poisoning. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:292. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.1.16310a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nogue Xarau S, Duenas Laita A. Intoxicacion por paraquat: un puzzle al que le faltan piezas. Med Clin (Barc) 2000;115:546–8. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7753(00)71619-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hwang K-Y, Lee E-Y, Hong S-Y. Paraquat intoxication in Korea. Arch Environ Health. 2002;57:162–6. doi: 10.1080/00039890209602931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]