The field of prostate cancer screening is filled with uncertainty. We are turning healthy men into patients suffering from cancer (with all that that entails) without any evidence that prostate cancer screening will save their lives.1 Even groups that champion screening for prostate cancer, such as the American Cancer Society, acknowledge this. They send out ambiguous messages that promote early detection, but do not recommend routine screening. For our patients, however, early detection and routine screening are one and the same1: a blood test and a rather uncomfortable examination!

In this uncertain context, strong stands on prostate cancer screening become indefensible, and decisions rest as much on values as they do on facts. The current trend is toward a joint decision-making process involving patients and their physicians. Here is the information that must be communicated to patients who are interested in this screening.

The message

You are 60 years old. According to Canadian statistics, out of 100 men your age, approximately 6 will have prostate cancer detected in the next 10 years. Out of these 6, 1 or 2 will die of prostate cancer, and 4 or 5 will die from other causes.2

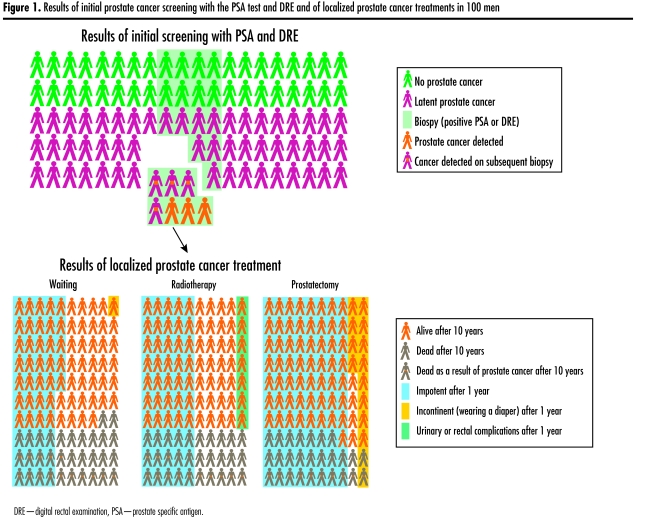

You should know that, out of 100 men your age, about 60 have prostate tumours (Figure 1).3,4 The vast majority of these tumours are microscopic and will never cause any problems. Some of these tumours will grow and cause problems, but it is impossible to determine which ones. This is why some people recommend that tumours that are detectable be identified through blood samples (prostate-specific antigen [PSA] testing) and a digital rectal examination (DRE). A PSA test helps to locate prostate tumours smaller than those that are found once symptoms appear.

Figure 1.

Results of initial prostate cancer screening with the PSA test and DRE and of localized prostate cancer treatments in 100 men

Of the 100 men who undergo tests for the first time (sensitivity 87%, specificity 80%,1,5 prevalence [of detectable tumours] 3%5,6), 22 will require another test: a prostate ultrasound, which is performed using a rectal probe and needle to collect small tissue samples from the prostate.

Among these 22 men, 3 will have cancer detected. When cancers are small and confined to the prostate, which is usually the case, we really have no reliable method of determining which are actually life-threatening. We can attempt to estimate risk by looking at the cells in tissue samples under a microscope. The most definitive answer, however, can only be found after the entire prostate is removed.

We do not know much about the other 19 men. For the most part, they have enlarged prostates, which explains abnormal PSA results. This does not mean that they don’t have cancer, however. If biopsy is repeated, cancer will be detected in 4 of these men.7 In the other 15 men, as in the 78 men who had normal results of PSA tests and DRE, cancer could appear or grow and become detectable one day. This is why some physicians suggest these tests be redone each year.

If we find that you have cancer limited to the prostate, you have 3 choices: have your prostate removed, undergo radiotherapy, or wait for the tumour to grow. It might also be recommended that you take hormones. Let’s take a look at what happens to 65-year-old men with localized tumours.8

After 10 years, out of 100 men who had surgery, 10 will die from prostate cancer, and 17 will die from other causes. Of 100 who chose to wait, 15 will die from prostate cancer, and 17 will die from other causes. Of the 100 who chose to have surgery, 80 will become impotent, and 14 will have to wear diapers for incontinence. Among those who chose to wait, 45 will become impotent, and only 1 will have to wear diapers.9 Among 100 men treated with radiotherapy, the mortality and risk of side effects will be somewhere between those for men who chose surgery and men who chose to wait.10

When tumours are discovered by testing men in good health, we do not know whether finding them early increases life expectancy. In 2008, the results of 2 studies that are specifically evaluating screening should give us this information. For now, the only thing we know for sure is the frequency of problems that result from treatment.

Conclusion

Undoubtedly, the way in which we present the risks and benefits associated with prostate cancer screening influences patients’ decisions. Men who use decision-making tools are less likely to undergo screening.11,12 Given the substantial uncertainties surrounding screening, the amount of information to communicate, and the amount of thinking patients have to do on what is most important to them, we should refrain from offering systematic screening and instead use decision-making tools that graphically illustrate the risks and benefits of treatment.13

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr Fernand Turcotte for his sound comments and his translation of Dr H. Gilbert Welch’s excellent book, Dois-je me faire tester pour le cancer? Peut-être pas et voici pourquoi [Should I get tested for cancer? Maybe not and here’s why].14

KEY POINTS

Most men with prostate tumours will die from causes other than prostate cancer.

There is no reliable method for distinguishing between screened tumours that require treatment and screened tumours that do not (and that it probably would have been better not to look for…and find).

At this time, there is no proof that screening for prostate cancer can save lives.

Decision-making tools help men to make choices that are based on both the best evidence and their own values.

References

- 1.Meyer F, Fradet Y. Prostate cancer: 4. Screening. CMAJ. 1998;159:968–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Société canadienne du cancer, Institut national du cancer du Canada, Statistique Canada, Registres du cancer des provinces et des territoires, Agence de santé publique du Canada. Statistiques canadiennes sur le cancer 2007. Ottawa, Ont: Institut national du cancer du Canada; 2007. [Accessed 2007 May 3]. Available from: http://www.ncic.cancer.ca/vgn/images/portal/cit_86755361/21/39/1835950433cw_2007stats_fr.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Montie JE, Wood DP, Jr, Pontes JE, Boyett JM, Levin HS. Adenocarcinoma of the prostate in cystoprostatectomy specimens removed for bladder cancer. Cancer. 1989;63(2):381–5. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890115)63:2<381::aid-cncr2820630230>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sakr WA, Grignon DJ, Haas GP, Heilbrun LK, Pontes JE, Crissman JD. Age and racial distribution of prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Eur Urol. 1996;30(2):138–44. doi: 10.1159/000474163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mistry K, Cable G. Meta-analysis of prostate-specific antigen and digital rectal examination as screening tests for prostate carcinoma. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2003;16(2):95–101. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.16.2.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andriole GL, Levin DL, Crawford ED, Gelmann EP, Pinsky PF, Chia D, et al. Prostate cancer screening in the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial: findings from the initial screening round of a randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(6):433–8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roobol MJ, van der Cruijsen IW, Schroder FH. No reason for immediate repeat sextant biopsy after negative initial sextant biopsy in men with PSA level of 4.0 ng/mL or greater (ERSPC, Rotterdam) Urology. 2004;63(5):892–7. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2003.12.042. discussion 897–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bill-Axelson A, Holmberg L, Ruutu M, Haggman M, Andersson SO, Bratell S, et al. Radical prostatectomy versus watchful waiting in early prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(19):1977–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steineck G, Helgesen F, Adolfsson J, Dickman PW, Johansson JE, Norlen BJ, et al. Quality of life after radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(11):790–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Warde P, Catton C, Gospodarowicz MK. Prostate cancer: 7. Radiation therapy for localized disease. CMAJ. 1998;159:1381–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frosch DL, Kaplan RM, Felitti V. The evaluation of two methods to facilitate shared decision-making for men considering the prostate-specific antigen test. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(6):391–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016006391.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evans R, Edwards A, Brett J, Bradburn M, Watson E, Austoker J, et al. Reduction in uptake of PSA tests following decision aids: systematic review of current aids and their evaluations. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;58(1):13–26. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Institut de recherche en santé d’Ottawa. Outils de prise de décision pour les patients. Ottawa, Ont: Institut de recherche en santé d’Ottawa; 1999. [Accessed 2007 May 3]. Available at: http://decisionaid.ohri.ca/francais/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Welch HG. Dois-je me faire tester pour le cancer? Peut-être pas et voici pourquoi. Quebec, Que: University of Laval Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]