Abstract

The solvent-tolerant strain Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1E has been engineered for biotransformation of toluene into 4-hydroxybenzoate (4-HBA). P. putida DOT-T1E transforms toluene into 3-methylcatechol in a reaction catalyzed by toluene dioxygenase. The todC1C2 genes encode the α and β subunits of the multicomponent enzyme toluene dioxygenase, which catalyzes the first step in the Tod pathway of toluene catabolism. A DOT-T1EΔtodC mutant strain was constructed by homologous recombination and was shown to be unable to use toluene as a sole carbon source. The P. putida pobA gene, whose product is responsible for the hydroxylation of 4-HBA into 3,4-hydroxybenzoate, was cloned by complementation of a Pseudomonas mendocina pobA1 pobA2 double mutant. This pobA gene was knocked out in vitro and used to generate a double mutant, DOT-T1EΔtodCpobA, that was unable to use either toluene or 4-HBA as a carbon source. The tmo and pcu genes from P. mendocina KR1, which catalyze the transformation of toluene into 4-HBA through a combination of the toluene 4-monoxygenase pathway and oxidation of p-cresol into the hydroxylated carboxylic acid, were subcloned in mini-Tn5Tc and stably recruited in the chromosome of DOT-T1EΔtodCpobA. Expression of the tmo and pcu genes took place in a DOT-T1E background due to cross-activation of the tmo promoter by the two-component signal transduction system TodST. Several independent isolates that accumulated 4-HBA in the supernatant from toluene were analyzed. Differences were observed in these clones in the time required for detection of 4-HBA and in the amount of this compound accumulated in the supernatant. The fastest and most noticeable accumulation of 4-HBA (12 mM) was found with a clone designated DOT-T1E-24.

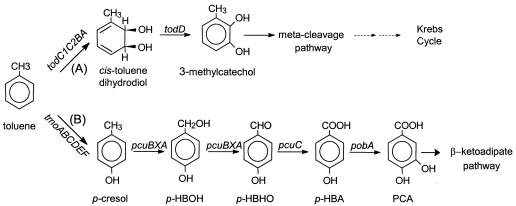

Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1E, a rifampin-resistant derivative of strain DOT-T1, is highly resistant to solvents, with the logarithm of the partition coefficient in a mixture of octanol and water (log Pow) being higher than 2.5. This strain is able to thrive in the presence of supersaturating concentrations of toluene. This aromatic compound serves as a carbon and energy source for the bacteria (17). The metabolic route for the mineralization of toluene by DOT-T1E is the Tod pathway, in which toluene is oxidized to 3-methylcathecol, which in turn is channeled to Krebs cycle intermediates via a meta-cleavage pathway (13) (Fig. 1, pathway A).

FIG. 1.

Two catabolic routes for aerobic catabolism of toluene. Pathway A shows toluene dioxygenase reactions used by P. putida DOT-T1E. todC1C2BA code for toluene dioxygenase, and todD encodes for cis-toluene dihydrodiol dehydrogenase. Pathway B shows T4MO reactions used by P. mendocina KR1. p-HBOH, p-hydroxybenzylalcohol; p-HBHO, p-hydroxybenzylaldehyde; p-HBA, p-hydroxybenzoate; PCA, protocatechuate. tmoABCDEF code for T4MO; pcuCAXB are p-cresol utilization genes; and pobA codes for p-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase.

In Pseudomonas mendocina KR1, toluene 4-monooxygenase (T4MO) is responsible for the first step of toluene catabolism (26) (Fig. 1, pathway B). By the activity of T4MO, encoded by the tmo genes, toluene is hydroxylated into p-cresol, which is further oxidized by the products of the pcu genes (28) to 4-hydroxybenzoate (4-HBA).

4-HBA is an added-value compound used in the synthesis of paraben and methylparaben, which are p-hydroxybenzoic acid alkylic ester derivatives that are of great interest for the synthesis of liquid glass (9) and as antimicrobial agents (23, 24). The potential to use 4-HBA as a carbon source is widespread in gram-negative soil bacteria, and it is not a unique property of species that have the T4MO pathway as the toluene catabolic pathway. 4-HBA is hydroxylated to 3,4-dihydroxybenzoate by the activity of the pobA product. 3,4-Dihydroxybenzoate undergoes ortho cleavage and is catabolized via the β-ketoadipate pathway (7).

The high tolerance of DOT-T1E to organic solvents makes this strain a good candidate for biotransformation and particularly for conversion of highly toxic substrates, such as toluene, into 4-HBA. Strain DOT-T1E tolerates up to 18 g of 4-HBA, the product of the biotransformation, per liter. This value increases to 30 g/liter when cells are preinduced with 4-HBA (18). P. mendocina KR1 is considerably less tolerant to toluene and 4-HBA than P. putida DOT-T1E; it tolerates less than 0.1% (vol/vol) toluene and 8.5 g of 4-HBA per liter (unpublished observations), and there is subsequent loss of viability during the process (Ben-Bassat, unpublished results).

The rationale behind this study was to recruit the appropriate enzymatic machinery for biotransformation of toluene into 4-HBA in the solvent-resistant DOT-T1E strain. To avoid misrouting of toluene and 4-HBA through the Tod and β-ketoadipate pathways, respectively, the first steps of these routes were inactivated in this strain. The double mutant was then equipped with the tmo and pcu genes from P. mendocina KR1 so that toluene was efficiently converted into 4-HBA, which remained in the liquid phase.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Description of bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

P. putida DOT-T1E (17) and P. mendocina KR1 (26) are prototrophic bacteria that have been described previously. P. mendocina KR1 has two copies of the pobA gene, pobA1 and pobA2. P. mendocina KR1-303 is a double mutant of P. mendocina KR1 in which both pobA genes are inactivated with streptomycin and kanamycin cassettes, so that it is unable to grow in 4-HBA (A. Ben-Bassat, M. Cattermole, A. A. Gatenby, K. J. Gibson, M. I. Ramos-González, J. L. Ramos, and S. Sariaslani, October 2002, U.S. patent application 20020151003). The P. putida DOT-T1EΔtodCpobA double mutant, which is not able to use toluene and 4-HBA as carbon sources, was generated in this study.

Mobilizable but not self-transmissible plasmids were transferred to recipient hosts by using triparental mating involving Escherichia coli HB101 bearing the helper plasmid pRK600. Plasmids with the replication origin ori R6K were maintained in E. coli CC118 λpir (8). Plasmids used and constructed in this study are listed in Table 1. E. coli and Pseudomonas strains were cultivated in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium or modified M9 minimal medium supplemented with 25 mM glucose and/or toluene in the gas phase as a carbon source (13), and they were incubated at 37 and 30°C, respectively. Competent E. coli DH5αF′ cells were used in transformation experiments (27). Electrotransformed cells were incubated in SOC medium for 1 to 2 h to allow expression of the acquired antibiotic resistance markers. Antibiotics were added as required to the media at the following concentrations: ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; chloramphenicol, 30 μg/ml; gentamicin, 10 μg/ml for E. coli strains and 100 μg/ml for pseudomonads; kanamycin, 25 μg/ml; streptomycin, 50 to 150 μg/ml; piperacillin, 90 μg/ml; tetracycline, 10 μg/ml; and trimethropim, 75 μg/ml. Potassium tellurite was used at a concentration of 15 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid(s) | Relevant characteristicsa | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| pANA52 | Apr Kmr, 2.2-kb EcoRI fragment with Ω/Km interposon from pHP45Ω cloned in pUC18 | A. Segura |

| pBBR1MCS-5 | Gmr, oriT RK2 | 11 |

| pHP45Ω-Km | Apr Kmr, Ω/Km interposon | 4 |

| pHP45Ω-Sm | Apr Smr Spr, Ω/Sm interposon | 14 |

| pKNG101 | Smr, mobRK2 oriR6K sacBR | 10 |

| pMC4 | Smr, P. mendocina KR1 tmo/pcu gene cluster cloned at HindIII/BamHI sites in pGV1120 | A. A. Gatenby |

| pMIR15 | Tcr, chimeric cosmid of pLAFR3 carrying P. putida pobA | This study |

| pMIR17 | Apr, 4.5-kb EcoRI/XcaI fragment of pT1-125 carrying the todC1 to todD genes cloned at the EcoRI/SmaI sites of pUC18NB-H | This study |

| pMIR18 | Apr, 6-kb EcoRI/BamHI fragment of pMIR15 cloned in pUC19 | This study |

| pMIR20 | Apr, 1.8-kb SspI/EcoRI fragment of pT1-4, containing the todXF genes, cloned at the EcoRI site of pMIR17 | This study |

| pMIR21 | Apr, todF′ΔtodC1::kilAtelAB::′todC2 | This study |

| pMIR22 | Apr, todF′ΔtodC1::km::′todC2 | This study |

| pMIR27 | Apr Tmr, AT-2 transposon inserted into pobA of pMIR18 | This study |

| pMIR29 | Apr Smr, sacBR todF′ΔtodC1::km::′todC2 | This study |

| pMIR30 | Apr Smr, sacBR todF′ΔtodC1::km::′todC2 | This study |

| pMIR31 | Apr Smr Spr, derivative of pMIR27 with 2-kb SmaI fragment with Ω/Sm interposon at the unique NotI site in AT-2 transposon | This study |

| pMIR32 | Apr, 7.5-kb BamHI fragment of pMC4 containing the tmoXABCDEF genes inserted into pUC19 | This study |

| pMIR40 | Apr, 7.6-kb MluI/NheI fragment of pPCU17 containing the pcuRCAXB genes cloned at the HindII/XbaI sites of pUC18Not | This study |

| pMIR42 | Apr, 7.4-kb BamHI fragment of pMIR32 at the unique BamHI site of pMIR40 | This study |

| pMIR44 | Apr Tcr, 15-kb NotI fragment of pMIR42 with the pcu and tmo gene clusters cloned at the unique NotI site of mini-Tn5Tc of pUT/Tc | This study |

| pPCU17 | Apr, 7.5-kb MluI/NheI containing the pcuRCAXB genes inserted into pSL1180 | A. A. Gatenby |

| pRK600 | Cmr, mob tra | 2 |

| pT1-4 | Apr, 3-kb fragament containing the todXF genes inserted into pUC19 | 13 |

| pT1-125 | Apr, ≈16-kb BamHI fragment that extends from todC1 to todT inserted into pUC19 | 13 |

| pUC18, pUC19 | Apr, MCS, Plac fused to the α peptide of LacZ | 25 |

| pUC18Not | Apr, identical to pUC18 but with NotI polylinker of pUC18-NotI | 8 |

| pUC18NB-H | Apr, identical to pUC18Not but with a deletion from BamHI to HindIII in the polylinker | This study |

| pUT/Tc | Apr Tcr, mini-Tn5Tc inserted into pUT | 2 |

| pUT/Tel | Apr Telr, mini-Tn5kilAtelAB inserted into pUT | 22 |

Apr, Cmr, Gmr, Kmr, Smr, Sp, Tcr, Telr, and Tmr, ampicillin, chloramphenicol, gentamicin, kanamycin, streptomycin, spectinomycin, tetracycline, tellurite, and trimethropim resistance, respectively; MCS, multiple cloning site.

Nucleic acid techniques.

Plasmid DNA was isolated with a Qiagen miniprep kit. All DNA manipulations were performed by using standard procedures (21). DNA fragments were recovered from agarose gels with a Quiaquick gel extraction kit. DNA probes were amplified by PCR with a Gene Amp PCR 2400 system with the appropriate primers and were labeled with digoxigenin-dUTP. Both DNA strands were sequenced by the dideoxy sequencing method by using an ABI Prism dRhodamine terminator kit (Applied Biosystems).

Plasmid construction.

pUC18NB-H is a pUC18Not derivative that lacks part of the polylinker of pUC18Not (8). This plasmid was generated after double digestion of pUC18Not with BamHI and HindIII and filling in of the protruding ends with the Klenow enzyme and deoxynucleoside triphosphates.

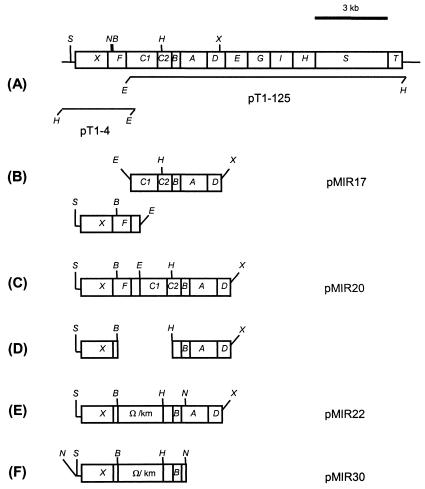

Plasmid pMIR22 is shown in Fig. 2. The entire tod operon was available in two plasmids: plasmid pT1-4, in which the todXF genes had been cloned; and plasmid pT1-125, containing the todC1C2BADEGIH gene cluster and the todST regulatory genes (13). Plasmid pMIR21 was obtained like pMIR22, but it had a 3-kb BamHI/HindIII fragment from pUT/Tel (22) containing the kilA telAB genes instead of the kanamycin resistance cassette. Plasmid pMIR29 was obtained like pMIR30 except that subcloning was with the NotI fragment of pMIR21 with the todF′ΔtodC1::kilAtelAB::′todC2 region.

FIG. 2.

Construction of plasmid pMIR30 used for generation of mutant DOT-T1EΔtodC by allelic exchange. (A) Physical organization of the tod genes. (B) A ∼4.5-kb EcoRI/XcaI fragment of pT1-125, which carried genes todC1 to todD, was subcloned at the EcoRI/SmaI sites of pUC18NB-H, generating plasmid pMIR17. (C) The 1.8-kb SspI/EcoRI fragment of pT1-4, containing the todXF genes, was subcloned at the EcoRI site of pMIR17 to obtain plasmid pMIR20 (the unique NotI site present in the SspI/EcoRI fragment was removed before cloning). (D) Most of the 3′ half of todF, the entire todC1 gene, and the 5′ end of todC2 were removed from pMIR20 as a 2.2-kb BamHI/HindIII fragment. (E) Insertion of a 2.2-kb Ω/Km cassette (4) to obtain pMIR22. (F) pMIR30 was obtained as a result of subcloning in pKNG101 of the NotI fragment of pMIR22, which contained the insertional deletion todF′ΔtodC1::km::′todC2. Restriction sites are indicated as follows: B, BamHI; E, EcoRI; H, HindIII; N, NotI; S, SspI; X, XcaI. Ω/km, interposon encoding kanamycin resistance.

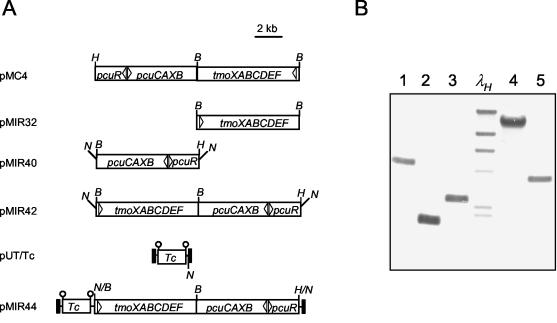

Plasmid pMIR44 bearing a mini-Tn5Tctmo/pcu transposon was constructed as shown in Fig. 3A. The transposon was based on a mini-Tn5Tc transposon borne by plasmid pUT-Tc (2).

FIG. 3.

Generation of the mini-Tn5Tctmo/pcu transposon and its different locations in the chromosomes of DOT-T1EΔtodCpobA derivatives. (A) Construction. The 7.4-kb BamHI fragment of pMC4 containing the tmoXABCDEF genes was subcloned at the BamHI site in the polylinker of pUC19, generating plasmid pMIR32. The 7.6-kb MluI/NheI fragment of pPCU17 (Ben-Bassat et al., U.S. patent application 20020151003) containing the pcuRCAXB genes was subcloned at the HindII/XbaI sites of pUC18NotI to obtain pMIR40. The 7.4-kb BamHI fragment of pMIR32 was incorporated into pMIR40 at the unique BamHI site to obtain plasmid pMIR42. Finally, the 15-kb NotI fragment of pMIR42 containing the pcu and tmo gene clusters was subcloned at the unique NotI site of pUT/Tc, which was located within the transposable element of the mini-Tn5Tc transposon, yielding plasmid pMIR44. Restriction sites are indicated as follows: B, BamHI; N, NotI; H, HindIII. Insertion sequences delimiting transposable elements are indicated by solid boxes. (B) Southern blot of exconjugants. Portions (10 μg) of total DNA of five independent clones were digested with EcoRV, which did not cut in the tetracycline (Tc) resistance determinant gene, and the fragments were analyzed by Southern blotting with a 429-bp digoxigenin-labeled PCR probe. The probe was amplified with the oligonucleotides 5′-CAACCCAGTCAGCTCCTTCC-3′ and 5′-GGACAGCTTCAAGGATCGCT-3′ and annealed internal to the tetracycline resistance gene. λHindIII (λH)was used as molecular weight marker. Lane 1, DOT-T1E-21; lane 2, DOT-T1E-17; lane 3, DOT-T1E-22; lane 4, DOT-T1E-24; lane 5, DOT-T1E-1-10a.

Isolation and inactivation of the P. putida pobA gene.

A P. putida GenBank constructed in cosmid pLAFR3 was transferred into P. mendocina KR1-303, and three independent P. mendocina exconjugants able to grow on 4-HBA as the sole carbon source were selected. The chimeric cosmids of these clones were isolated, their restriction patterns were determined, and the presence of pobA was analyzed by Southern blotting and hybridization with the P. mendocina pobA1 probe. A common 6-kb BamHI/EcoRI hybridization band was observed in all the cosmids (data not shown) and was subcloned in pUC19 to produce pMIR18. For sequencing of the insert of plasmid pMIR18, in vitro random transposition with a Primer Island transposition kit (PE Applied Biosystems) was carried out. Mutagenesis of pMIR18 with the AT-2 transposon yielded a mixture of plasmids containing the transposon at different positions. The position of the insertion was determined by sequencing with the specific primers P1 (plus strand) (5′-CAGGACATTGGATGCTGAGAATTCG-3′) and P1 (minus strand) (5′-CAGGAGCCGTCTATCCTGCTTGC-3′) present at either end of the transposable AT-2 element. One of the plasmids obtained in this way was pMIR27. Although pMIR27 carried an inactivated pobA gene as a result of in vitro insertion of the AT-2 transposon, the transposon's marker, trimethropim, did not achieve counterselection of P. putida DOT-T1E and was consequently not functional in the allelic exchange. To overcome this disadvantage, another marker, the Ω/Sm cassette, was incorporated at the unique NotI site present in the AT-2 transposon of pMIR27 to create plasmid pMIR31.

Electrotransformation of P. putida ΔtodCkm cells with pMIR31.

We used the procedure described by Enderle and Farwell (3) to electrotransform P. putida cells. Cells in 0.2-cm cuvettes were subjected to a high-voltage pulse (3,000 V) for 5 ms by using a MicroPulser electroporation apparatus (Bio-Rad). Cells were subsequently incubated in 1 ml of SOC medium for 2 h at 30°C and then harvested by centrifugation (13,000 × g for 2 min in a microcentrifuge), and the pellet was incubated overnight at the same temperature on a filter placed on an LB agar plate. The cells were finally resuspended in 1 ml of LB medium and plated on LB agar supplemented with kanamycin and streptomycin (25 and 150 μg/ml, respectively).

Quantitative detection of 4-HBA in the culture supernatant by high-performance liquid chromatography.

4-HBA that accumulated in culture supernatants was analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography by using a Hewlett-Packard model 1050 chromatograph equipped with a diode array detector and a 5-mm C18RP column (UltraCarb C30 Phenomenex; 15 cm by 4.6 mm). The column was first washed with a mixture of acetonitrile and a solution of 1% (vol/vol) acetic acid in water (2:8, vol/vol) for 2 min. A linear gradient was then applied to reach 60% (vol/vol) acetonitrile over 15 min. The flow rate was kept constant at 1 ml/min, and the detector was set at 230 and 254 nm to detect aromatic compounds.

RESULTS

Generation and stability of the toluene-minus derivative of DOT-T1E (todF′ΔtodC1::km::′todC2).

To block transformation of toluene into 3-methylcatechol in P. putida and with the intention of generating a stable mutant unable to oxidize toluene, we generated a 2.2-kb deletion comprising the complete todC1 gene and parts of the flanking todF and todC2 genes (Fig. 1).

Plasmids pMIR29 and pMIR30 are derivatives of the suicide vector pKNG101 (10), whose construction is described above (Fig. 2). These plasmids carry the insertional deletions todF′ΔtodC1::km::′todC2 and todF′ΔtodC1::kilAtelAB::′todC2, respectively, and were used as delivery plasmids to replace the wild-type toluene dioxygenase in the chromosome of DOT-T1E with the deleted version by homologous recombination. Details concerning the methods used for mobilization of these suicide plasmids, selection of merodiploid strains, and selection of mutants upon allelic exchange have been described previously (19). Two mutants unable to use toluene as a carbon source were isolated and designated ΔtodCkm and ΔtodCtel, respectively. Deletion of the todC1 gene in the chromosome of the toluene-minus isolates was confirmed by PCR with specific primers and by Southern blotting (data not shown). The stabilities of the two mutants were tested and were found to be identical: (i) after 90 generations of growth in LB medium under nonselective conditions (with no antibiotics), 100% of the cells were resistant either to kanamycin or to tellurite and were unable to grow in toluene; (ii) no growth was observed after 1 week of incubation in M9 liquid minimal media with toluene as the sole C source in the absence of selective pressure for the markers; and (iii) the reversion rate, determined by measuring reacquisition of the ability to grow on toluene for both clones tested by the drop plating technique, was less than 10−9.

Analysis of the sequence in the P. putida pobA-pobR region.

Plasmid pMIR27 was generated by in vitro random transposition with the AT-2 transposon as described above. This plasmid had the transposon inserted at the 5′ end of the pobA gene (between positions 123 and 124 after the ATG), with consequent interruption of the gene. The whole pobA gene and part of the pobR gene were identified in pMIR27. As in other pseudomonads, the two genes were transcribed divergently. The complete sequence of the pobA gene revealed that it consists of a 1,188-nucleotide open reading frame at positions 82783 to 83970 in the genome of P. putida KT2440 (accession number AE015451). The clone contained part of the pobR gene, whose putative start codon was located 173 nucleotides upstream of the ATG start site of the pobA gene, in the antiparallel strand. The overall levels of identity between the P. putida pobA gene and the P. mendocina pobA1 and pobA2 genes were 77 and 79%, respectively. The level of identity between the two P. mendocina pobA genes was 84%. At the protein level, the overall level of identity between the PobA1 and PobA2 proteins was about 90%, whereas the deduced amino acid sequence encoded by the P. putida pobA gene exhibited 83 and 84% identity with the P. mendocina PobA1 and PobA2 proteins, respectively.

Generation of 4-HBA-minus derivative of P. putida ΔtodCkm (double mutant ΔtodCpobA).

Plasmid pMIR31 was used as a delivery system for gene replacement by homologous recombination of the wild-type pobA allele by an inactivated copy. P. putida ΔtodCkm cells were eletrotransformed with pMIR31 as described above, and the resulting Kmr Smr clones were tested for the ability to grow on 4-HBA and for Pipr, the marker of pMIR31. One clone which was unable to use 4-HBA as a C source and which was Pips was isolated. The successful allelic exchange of the wild-type pobA gene for the inactivated copy in the ΔtodCkm/pobA::Sm double mutant was confirmed by Southern blotting (data not shown). The inactivated pobA gene was stable, and no revertants able to grow on 4-HBA were detected after 1 week of incubation in the presence of the hydroxylated carboxylic acid.

Stable transfer of mini-Tn5Tctmo/pcu into the chromosome of DOT-T1EΔtodCpobA.

The P. putida DOT-T1EΔtodCpobA mutant was mated with E. coli CC118λpir(pMIR44) in the presence of the helper organism E. coli(pRK600), and exconjugants of P. putida were selected on LB medium supplemented with kanamycin, streptomycin, and tetracycline at a rate of 5 × 10−8 exconjugant per recipient. From the exconjugants, six clones that were able to grow in minimal medium with glucose as fast as the parental strain were isolated. All of these exconjugants failed to grow with either toluene or 4-HBA as the sole carbon source because of the pobA mutation. The stability of each of the markers was tested. The six strains were cultivated on LB medium without antibiotics for about 100 generations. After serial dilutions were spread on LB medium, the results confirmed that 100% of the cells retained all antibiotic markers. The transposon was detected by Southern blotting in the chromosome of five of the isolates at different positions (Fig. 3B).

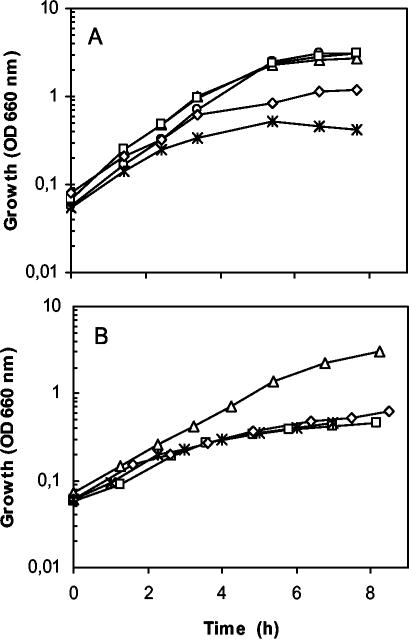

Effect of toluene on the growth and survival of P. putida DOT-T1E wild-type and mutant strains.

The sensitivity of bacterial cells to toluene, the substrate of the biotransformation reaction, might be critical during the process. The growth characteristics of the wild-type DOT-T1E strain, the null todC mutant strain, the double mutant ΔtodCpobA strain, and six independent exconjugants of the double mutant strain with mini-Tn5Tctmo/pcu were compared in LB medium and in glucose-supplemented M9 minimal medium with the appropriate antibiotics. All the strains exhibited similar growth curves in LB medium in the absence of toluene (data not shown). However, when toluene was supplied in the gas phase, the double ΔtodCpobA mutant exhibited the same growth profile as the wild-type strain, whereas all the strains bearing mini-Tn5Tctmo/pcu grew more slowly than the parental strains (Fig. 4A shows the growth of two 4-HBA producer clones as an example). This observation might have been due to the energy requirements for the biotransformation. In minimal medium in the absence of toluene, similar growth was observed for all of the strains; however, in the presence of toluene, the growth rates of the ΔtodCpobA double mutant and its producer derivatives were lower (the doubling time decreased from 65 to 200 min) (Fig. 4B). Toluene also had a negative effect on the highest cell density reached by the mutants.

FIG. 4.

Effect of toluene on the growth of P. putida strains. (A) Overnight LB medium cultures were diluted in the same medium with toluene in the gas phase, and growth was monitored by measuring turbidity. The strains used were DOT-T1E (○), the ΔtodC single mutant (▵), the ΔtodCpobA double mutant (□), and two derivatives of ΔtodCpobA carrying tmo/pcu genes in the chromosome, DOT-T1E-24 (⋄) and DOT-T1E-1-10a ([ast]). (B) Same as panel A except that glucose-supplemented M9 minimal medium was used instead of LB medium. The appropriate antibiotics were added to the cultures. OD 660 nm, optical density at 660 nm.

Production of 4-HBA by DOT-T1EΔtodCpobA derivatives carrying mini-Tn5Tctmo/pcu in the chromosome.

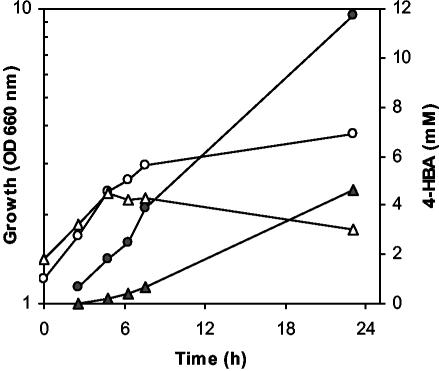

The transposable element conferred the ability to transform toluene into 4-HBA, a compound that could not be used as a C source by the ΔtodCpobA derivatives and accumulated in the culture medium. In order to determine the effect of the insertion site of the minitransposon on the efficiency of 4-HBA, a screening experiment with a pool of independent exconjugants was carried out to analyze possible differences in 4-HBA production. The production of 4-HBA was studied with resting cells at a high cell density (optical density at 660 nm, about 10 U; 1010 CFU/ml) in glucose-supplemented M9 minimal medium (Fig. 5A). Cell density was constant in the experiment (data not shown), whereas production of 4-HBA exhibited a lag in all cases, which varied from 3 h in clon-24 to more than 24 h in clon-1-5A. The concentration of 4-HBA was as high as 10.5 mM in the most proficient strain, clon-24, which exhibited a rate of production of 0.4 mM/h during the interval when lineal production occurred. The lowest concentration detected, less than 4 mM, was the concentration observed with clon-17. P. mendocina KR-303 was used as a 4-HBA-producing control strain (Ben-Bassat et al., U.S. patent application 20020151003). The kinetics of 4-HBA accumulation in this strain are shown in Fig. 5B. The time required for detection of the hydroxylated aromatic acid in the supernatant of this strain was similar to the lowest lag time determined for any of the P. putida producers, although an unexpected decrease in the amount accumulated was observed after 30 h of incubation. Production of 4-HBA by P. putida DOT-T1E derivatives was also analyzed at a lower cell density (turbidity at 660 nm, 1 U) along the growth curve. Cells in the early stationary phase were removed from exhausted medium and amended with fresh medium. Under these conditions, growth of the cells at the expense of glucose was observed with concomitant 4-HBA production. The production by two clones is shown in Fig. 6. The time required for detection of certain amounts of 4-HBA was similar to the time required with resting cells.

FIG. 5.

Accumulation kinetics of 4-HBA in the supernatants of resting cells of P. putida (A) and P. mendocina (B) derivative strains. (A) Cells from overnight cultures corresponding to 150 ml of glucose-supplemented M9 minimal medium, after exhausted medium was removed by centrifugation, were washed in M9 buffer and then suspended in fresh medium to obtain an optical density at 660 nm of 10 (25 ml), and toluene was supplied in the gas phase. Samples (800 μl) were centrifuged for 10 min at 13,000 × g, and 20 μl of each cell-free supernatant was analyzed to determine the amount of 4-HBA by high-performance liquid chromatography as described in Materials and Methods. For quantification, a 4-HBA standard was used. Symbols: ○, DOT-T1E-1-5a; ▵, DOT-T1E-17; □, DOT-T1E-21; ⋄, DOT-T1E-24; [ast], DOT-T1E-1-10a. (B) Conditions were like those described above for panel A. P. mendocina KR1-303 cell density (○) and 4-HBA accumulation (•) were determined. Duplicate cultures were examined. The data are averages of two values for one typical culture, and the standard deviation was less than 5%. OD 660 nm, optical density at 660 nm.

FIG. 6.

Accumulation kinetics of 4-HBA in the supernatant of P. putida derivatives DOT-T1E-24 (circles) and DOT-T1E-1-10a (triangles). Early-stationary-phase cells from glucose-supplemented M9 minimal medium cultures (15 ml) were centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 10 min, washed in M9 buffer, and suspended in 30 ml of fresh medium with toluene supplied in the gas phase. 4-HBA accumulation was determined as described in the legend to Fig. 5, and cell density (solid symbols) was determined by measuring the optical density at 660 nm (OD 660 nm) (open symbols). Duplicate cultures were examined. The data are averages of two values for one typical culture, and the standard deviation was less than 5%.

DISCUSSION

In this study, P. putida DOT-T1E, a highly solvent-tolerant strain, was genetically modified to produce 4-HBA from toluene. The hydroxylated aromatic compound is used in the synthesis of parabens and methylparabens, which are of great interest as antimicrobial agents (23, 24) and for production of liquid glass (9).

Biotransformation of toluene to 4-HBA occurs naturally in P. mendocina KR1 through the T4MO pathway, which is responsible for the hydroxylation of toluene to p-cresol and the subsequent oxidation of p-cresol to 4-HBA by the enzymes encoded by the p-cresol utilization genes (pcu) (28) (Fig. 1, pathway B). In the wild type, 4-HBA is used as a carbon source by action of the p-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase and the subsequent β-ketoadipate pathway, so that the amount of hydroxylated acid in the supernatant is undetectable (data not shown). However, in strain KR1-303, a pobA1 pobA2 double mutant (Ben-Bassat et al., U.S. patent application 20020151003), accumulation of up to 6.3 mM 4-HBA was detected after 10 h in batch cultures, and there was a slight increase to 7.5 mM after 30 h of incubation (Fig. 5B).

The mutant DOT-T1EΔtodC was as tolerant as the wild type to a sudden shock of toluene and 4-HBA, which were added as reported previously (5, 16). The independence of solvent tolerance and biodegradation capacity was not unexpected. Although metabolism of toxic chemicals can help reduce their toxicity, this mechanism should contribute considerably less than other major mechanisms as efflux pumps in protecting cell viability (15). Like the DOT-T1EΔtodC single mutant, the todC pobA double mutant was as tolerant as the wild type to a sudden shock of toluene and 4-HBA (data not shown), despite the fact that it did not use any of the compounds as a carbon source.

The tmo and pcu gene clusters in mini-Tn5Tctmopcu (Fig. 3) were responsible for the production of 4-HBA by resting cells of the todC pobA double mutant, and different amounts of the compound were detected for independent clones (range, 3.5 to 10.5 mM) (Fig. 5A). In the clones with the highest rates of 4-HBA production, DOT-T1E-21 and DOT-T1E-24 (0.38 and 0.4 mM/h, respectively), the concentration reached a maximum after 28 to 30 h. Addition of a carbon source (glucose) to the samples did not restore the production (data not shown), in agreement with the previous observation that the rate-limiting step in 4-HBA production is T4MO, which has a half-life of 28 h (12). The fact that 4-HBA production from glucose has been described for a series of recombinant E. coli strains should be taken into account; this production occurs through a complex process that involves up to eight steps after phosphoenolpyruvate (1), compared with the four steps in our system. In E. coli in fermentors, the level of 4-HBA accumulation was about one-third (12 g/liter) the level obtained under similar conditions with Pseudomonas (6).

Expression of the tmo promoter in P. mendocina KR1 requires a two-component signal transduction system designated tmoS/tmoT (20). In DOT-T1E, as well as in the 4-HBA-producing derivatives generated in this study, there are homologues of tmoS/tmoT (i.e., todST, the two-component signal transduction system that regulates expression of the tod operon) (13). In a recent study, activation of tmo genes by the TodST system was confirmed (20), and this cross-activation, together with the robustness of DOT-T1E, made this strain a good candidate for biotransformation of toluene into 4-HBA.

A pobA mutant derivative of P. putida KT2440 was generated in this study. Mini-Tn5Tctmopcu was recruited into this mutant, and after a pool of exconjugants with the transposon at different positions in the chromosome was screened, as done previously with the ΔtodCpobA derivatives, no 4-HBA production from toluene was detected. Since there are no homologues of the TmoST regulator in strain KT2440 (20), the lack of induction of the tmo genes was most probably responsible for the failure of biotransformation in this strain. In a previous study with a KT2440 pobA strain, which carried tmo and pcu gene clusters in two transposons inserted into the chromosome, production of 4-HBA from toluene was reported (12). In that strain, which did not have tmoST genes, toluene-dependent activation from the tmoX promoter was not feasible. Instead, inducible promoters in the presence of appropriate activators were used.

Although we did not observe any decrease in the accumulation of 4-HBA with the producer derivatives of ΔtodCpobA, such a decrease was observed with P. mendocina KR1 clon-303 (Fig. 5B). To our knowledge, catabolic turnover should not have been the reason for the decrease in the amount of 4-HBA observed since both pobA genes present in P. mendocina KR1-303 had been knocked out and the possibility of there being a third pobA gene was eliminated by hybridization (data not shown). However, 4-HBA could have served as a substrate for enzymes involved in catabolism of aromatic compounds other than p-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase. In fact, evidence of 4-HBA metabolism via alternative pathways has been obtained for the wild-type strain DOT-T1E (Ramos-González, unpublished data).

Toluene in the gas phase slowed the growth of producing strains (Fig. 4). This effect could have been a consequence of the extra energy demand due to transformation of toluene. However, the same result was observed with the nonproducing todC pobA strain. The effect of toluene was not due to a decrease in tolerance to toluene or 4-HBA since all strains were as resistant as the wild-type and ΔtodCpobA strains (data not shown). The negative effect of toluene was not life-threatening for the exponentially growing cells that accumulated 4-HBA in the supernatant at rates ranging from 0.23 to 0.5 mM/h (Fig. 6). The strain that accumulated larger amounts of 4-HBA was clone DOT-T1E-24 (which accumulated up to 12 mM).

In short, our results indicate that inactivation of the tod and pobA genes of P. putida DOT-T1E and incorporation of the tmo and pcu genes produce suitable, highly stable clones that can be used for biotransformation of toluene into 4-HBA, a compound of great industrial interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the DuPont Company.

We greatly thank Anthony A. Gatenby for supplying plasmid pMC4. We also thank Ana Hurtado for DNA sequencing, Carmen Lorente and M. Mar Fandila for secretarial assistance, and M. Espinosa for his kind help with improving the language.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barker, J. L., and J. W. Frost. 2001. Microbial synthesis of p-hydroxybenzoic acid from glucose. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 76:376-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Lorenzo, V., M. Herrero, U. Jakubzik, and K. N. Timmis. 1990. Mini-Tn5 transposon derivatives for insertion mutagenesis, promoter probing, and chromosomal insertion of cloned DNA in gram-negative eubacteria. J. Bacteriol. 172:6568-6572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Enderle, P. J., and M. A. Farwell. 1998. Electroporation of freshly plated Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa cells. BioTechniques 25:954-958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fellay, R., J. Frey, and H. Krisch,. 1987. Interposon mutagenesis of soil and water bacteria: a family of DNA designed for in vitro insertional mutagenesis of Gram-negative bacteria. Gene 52:147-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Godoy, P., M. I. Ramos-González, and J. L. Ramos. 2001. Involvement of the TonB system in tolerance to solvents and drugs in Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1E. J. Bacteriol. 183:5285-5292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grelak, R. L., and K. K. Chen. 1998. Method for the production of para-hydroxybenzoate in Pseudomonas mendocina. Patent Corporation Treaty application WO 98/56920.

- 7.Harwood, C. S., and R. E. Parales. 1996. The β-ketoadipate pathway and the biology of self-identity. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 50:553-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herrero, M., V. De Lorenzo, and K. N. Timmis. 1990. Transposon vectors containing non-antibiotic resistance selection markers for cloning and stable chromosomal insertion of foreign genes in gram-negative bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 172:6557-6567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang, K., Y. G. Lin, and H. H. Winter. 1992. p-Hydroxybenzoate/ethylene terephthalate copolyester: structure of high-melting crystals formed during partially molten state annealing. Polymer 33:4533-4537. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaniga, K., I. Delor, and G. R. Cornelis. 1991. A wide-host-range suicide vector for improving reverse genetics in Gram-negative bacteria: inactivation of the blaA gene of Yersinia enterocolitica. Gene 109:137-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kovach, M. E., P. H. Elzer, D. S. Hill, G. T. Robertson, M. A. Farris, R. M. Roop II, and K. M. Peterson. 1995. Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene 166:175-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller, E. S., Jr., and S. W. Peretti. 2001. Toluene bioconversion to p-hydroxybenzoate by fed-batch cultures of recombinant Pseudomonas putida. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 77:340-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mosqueda, G., M. I. Ramos-González, and J. L. Ramos. 1999. Toluene metabolism by the solvent-tolerant Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1E strain, and its role in solvent impermeabilization. Gene 232:69-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prentki, P., and H. M. Krisch. 1984. In vitro insertional mutagenesis with a selectable DNA fragment. Gene 29:303-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramos, J. L., E. Duque, M. T. Gallegos, P. Godoy, M. I. Ramos-Gonzalez, A. Rojas, W. Teran, and A. Segura. 2002. Mechanisms of solvent tolerance in gram-negative bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 56:743-768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramos, J. L., E. Duque, P. Godoy, and A. Segura. 1998. Efflux pumps involved in toluene tolerance in Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1E. J. Bacteriol. 180:3323-3329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramos, J. L., E. Duque, M. J. Huertas, and A. Haidour. 1995. Isolation and expansion of the catabolic potential of a Pseudomonas putida strain able to grow in the presence of high concentrations of aromatic hydrocarbons. J. Bacteriol. 177:3911-3916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramos-González M. I., P. Godoy, M. Alaminos, A. Ben-Bassat, and J. L. Ramos. 2001. Physiological characterization of Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1E tolerance to p-hydroxybenzoate. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4338-4341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramos-González, M. I., and S. Molin. 1998. Cloning, sequencing, and phenotypic characterization of the rpoS gene from Pseudomonas putida KT2440. J. Bacteriol. 180:3421-3431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramos-González, M. I., M. Olson, A. A. Gatenby, G. Mosqueda, M. Manzanera, M. J. Campos, S. Vílchez, and J. L. Ramos. 2002. Cross-talk between two-component signal transduction systems of two different toluene catabolic pathways from bacteria of the genus Pseudomonas. J. Bacteriol. 184:7062-7067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 22.Sanchez-Romero, J. M., R. Diaz-Orejas, and V. De Lorenzo. 1998. Resistance to tellurite as a selection marker for genetic manipulations of Pseudomonas strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:4040-4046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soni, M. G., S. L. Taylor, N. A. Greenberg, and G. A. Burdock. 2002. Evaluation of the health aspects of methyl paraben: a review of the published literature. Food Chem. Toxicol. 40:1335-1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sznitowska, M., S. Janicki, E. A. Dabrowska, and M. Gajewska. 2002. Physicochemical screening of antimicrobial agents as potential preservatives for submicron emulsions. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 15:489-495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vieira, J., and J. Mesing. 1982. The pUC plasmid: an M13mp7-derived system for insertion mutagenesis and sequencing with synthetic universal primers. Gene 19:259-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whited, G. M., and D. T. Gibson. 1991. Toluene-4-monooxygenase, a three-component enzyme system that catalyses the oxidation of toluene to p-cresol in Pseudomonas mendocina KR1. J. Bacteriol. 173:3010-3016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woodcock, D. M., P. J. Crowther, J. Doherty, S. Jefferson, E. DeCruz, M. Noyer-Weidner, S. S. Smith, M. Z. Michael, and M. W. Graham. 1989. Quantitative evaluation of Escherichia coli host strains for tolerance to cytosine methylation in plasmid and phage recombinants. Nucleic Acids Res. 17:3469-3478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wright, A., and R. H. Olsen. 1994. Self-mobilization and organization of the genes encoding the toluene metabolic pathway of Pseudomonas mendocina KR1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:235-242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]