Abstract

The lignocellulolytic fungus Aureobasidium pullulans NRRL Y 2311-1 produces feruloyl esterase activity when grown on birchwood xylan. Feruloyl esterase was purified from culture supernatant by ultrafiltration and anion-exchange, hydrophobic interaction, and gel filtration chromatography. The pure enzyme is a monomer with an estimated molecular mass of 210 kDa in both native and denatured forms and has an apparent degree of glycosylation of 48%. The enzyme has a pI of 6.5, and maximum activity is observed at pH 6.7 and 60°C. Specific activities for methyl ferulate, methyl p-coumarate, methyl sinapate, and methyl caffeate are 21.6, 35.3, 12.9, and 30.4 μmol/min/mg, respectively. The pure feruloyl esterase transforms both 2-O and 5-O arabinofuranosidase-linked ferulate equally well and also shows high activity on the substrates 4-O-trans-feruloyl-xylopyranoside, O-{5-O-[(E)-feruloyl]-α-l-arabinofuranosyl}-(1,3)-O-β-d-xylopyranosyl-(1,4)-d-xylopyranose, and p-nitrophenyl-acetate but reveals only low activity on p-nitrophenyl-butyrate. The catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) of the enzyme was highest on methyl p-coumarate of all the substrates tested. Sequencing revealed the following eight N-terminal amino acids: AVYTLDGD.

Links between plant cell wall polysaccharides and lignin polymers are commonly formed as substituents by hydroxycinnamic acids like ferulic and p-coumaric acid (30, 31). Ferulic acid is usually esterified at position C-5 to α-l-arabinofuranosyl side chains in arabinoxylans, at position C-2 to α-l-arabinofuranosyl residues in arabinans, at position C-6 to β-galactopyranosyl residues in pectic substances and galactans (37), and at position C-4 to α-d-xylopyranosyl residues in xyloglucans (21). Ferulic acids can also be found forming several types of dehydrodimers (17, 20, 21, 26) and can be involved in ester and/or ether linkages with lignin components (4, 26). Hydroxycinnamates can therefore be seen as important structural components, providing cell wall integrity and hence protecting plants against digestion by plant-invading microorganisms (8, 18, 22).

Several hydroxycinnamic ester-hydrolyzing enzymes have been isolated and characterized (39, 40), some have been cloned (2, 10, 12, 16), and three-dimensional structures are now available (29). Extracellular feruloyl esterases are produced by plant-invading microorganisms in addition to other lignocellulose-degrading enzymes but have also been reported to be endogenous to plants, such as in germinating barley (36). A whole range of different substrates, both natural and synthesized, have been used to characterize feruloyl esterases, such as O-{5-O-[(E)-feruloyl]-α-l-arabinofuranosyl}-(1,3)-O-β-d-xylopyranosyl-(1,4)-d-xylopyranose (FAXX) (14), phenolic acid methyl esters (methyl-4-hydroxy-3-methoxycinnamate) (15), or 4-nitrophenyl 5-O-trans-feruloyl-α-l-arabinofuranoside (NPh-5-Fe-Araf) (1). Feruloyl esterases have been classified according to sequence homologies (9) and into types according to their specificities for particular substrates (14, 39, 40).

The black yeast Aureobasidium pullulans is a ubiquitous saprophyte found on leaves of plants with biotechnological applications (7, 11). However, only xylanase (27), β-glucosidase (35), and α-l-arabinofuranosidase (34) have been purified and characterized from the lignocellulose-degrading enzyme system of this organism. Recently, it was shown that feruloyl esterase contributes substantially to the lignocellulose-degrading potential of A. pullulans (33). Using synthetic and natural substrates, we demonstrate the broad substrate spectrum of this high-molecular-mass enzyme.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strain and fermentation conditions.

A. pullulans NRRL Y 2311-1 was maintained on potato dextrose agar (7). Feruloyl esterase activity was produced by growing A. pullulans in a 2-liter bench top fermentor containing yeast nitrogen base (6.7 g/liter), l-asparagine (2 g/liter), and KH2PO4 (5 g/liter) with 10 g of birchwood xylan (Sigma)/liter. After 60 h of cultivation at 30°C, at an agitation speed of 400 rpm, and at an aeration rate of 1,000 ml/min, the medium was separated from the cells by centrifugation (5,000 × g, 5 min) and the supernatant was stored at 4°C after 10-fold concentration in an Amicon ultrafiltration cell (Millipore) fitted with a 30-kDa-molecular-mass-cutoff membrane.

Purification of feruloyl esterase.

The purification of feruloyl esterase was carried out on an ÄKTA purifier (Amersham Biosciences). The concentrated supernatant was separated on a Q Sepharose Fast Flow column at a flow rate of 5 ml/min. Unbound material was eluted with 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7) whereas bound proteins were eluted by applying a gradient of NaCl (0 → 1 M) in 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7. Fractions containing feruloyl esterase activity were pooled and concentrated using a 10-ml stirred ultrafiltration unit fitted with a 10-kDa-molecular-mass-cutoff membrane. Samples (20 mg of protein) were separated on a HiTrap Phenyl FF column (Amersham Biosciences) at a flow rate of 4 ml/min. Unbound samples were eluted with 50 mM Tris (pH 7) containing 1.2 M (NH4)2SO4. Bound samples were eluted by a linear gradient of decreasing (NH4)2SO4 (1.2 → 0 M). Samples were pooled (100 μl), applied to a Superdex 75 HR 10/30 column (Amersham Biosciences), and separated by isocratic elution with 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7, at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. For molecular mass determination of the purified feruloyl esterase, the column was calibrated with myosin (205 kDa), β-galactosidase (116 kDa), phosphorylase b (97.4 kDa), serum albumin (66 kDa), and ovalbumin (45 kDa) (Sigma).

Feruloyl esterase activity and protein determination.

Total protein in crude and purified samples was determined using the Coomassie blue assay (5) (Bio-Rad Laboratories) with bovine serum albumin as standard. Fractions generated during the purification of the enzyme from A. pullulans culture supernatant were routinely assayed spectrophotometrically for feruloyl esterase activity by using 0.6 mM NPh-5-Fe-Araf as substrate (1).

PAGE.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was performed as described previously (25) with high-range molecular weight markers (Sigma). Isoelectric focusing was performed using Ready-Gels (pH 3 to 10; Bio-Rad Laboratories) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Esterase activity was assayed in situ on isoelectric focusing and SDS-polyacrylamide gels with 10 g of naphthol-AS-d-chloroacetate (Sigma)/liter as substrate (19).

Protein deglycosylation.

The degree of Asp-linked glycosylation of the purified feruloyl esterase was determined by digesting the protein with an N-glycosidase F deglycosylation kit (Roche Diagnostics) according to the manufacturer's instructions and separating it as described above by SDS-10% PAGE.

Enzyme assays.

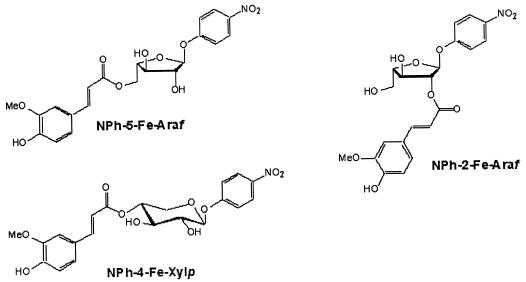

Methyl ferulate (MFA), methyl caffeate (MCA), methyl p-coumarate (MpCA), methyl sinapate (MSA), and FAXX isolated from wheat bran were used as substrates in an assay as described previously (14, 15). Specific activity (units) is expressed as micromoles of hydroxycinnamic acid released per minute per milligram of protein. Acetyl esterase and butyryl esterase activities were determined as described previously (19). Specific activity (units) is expressed as micromoles of 4-nitrophenol released per minute per milligram of protein. Another spectrophotometric assay (1) was used to determine enzymatic activity on NPh-5-Fe-Araf, 4-nitrophenyl 2-O-trans-feruloyl-α-l-arabinofuranoside (NPh-2-Fe-Araf), and 4-nitrophenyl 4-O-trans-feruloyl-xylopyranoside (NPh-4-Fe-Xylp) (Fig. 1). Aspergillus oryzae feruloyl esterase (38) was used for comparative purposes.

FIG. 1.

Structures of feruloyl esterase substrates NPh-5-Fe-Araf, NPh-2-Fe-Araf, and NPh-4-Fe-Xylp.

Protein sequencing.

Prior to sequencing, purified feruloyl esterase was concentrated by passing the protein through a ProSorb cartridge (Applied Biosystems). The N-terminal amino acid sequence was determined by Edman degradation of the purified feruloyl esterase with an ABI Procise 491 sequencer (Applied Biosystems).

RESULTS

Production and purification of feruloyl esterase.

A. pullulans feruloyl esterase reached a maximum extracellular specific activity of 1.6 U/mg after 60 h when cultivated on 10 g of birchwood xylan/liter (32). The enzyme was isolated from the culture supernatant by ultrafiltration and purified (Table 1). After anion-exchange chromatography, feruloyl esterase activity was assigned to the unbound fraction at pH 7. After hydrophobic interaction chromatography, feruloyl esterase activity was again recovered from the unbound fraction. Finally, size-exclusion chromatography yielded a single active peak that contained feruloyl esterase purified 43-fold with a 13% yield compared to the crude culture supernatant (Table 1). This protein was subjected to further characterization.

TABLE 1.

Purification of A. pullulans feruloyl esterasea

| Purification step | Vol (ml) | Sp act (U/mg of protein) | Total activity (U) | Purification (fold) | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude culture supernatant | 2,000 | 1.6 | 695 | 1 | 100 |

| Ultrafiltration | 200 | 10.8 | 472 | 6.8 | 68 |

| Anion-exchange chromatography | 25 | 32.8 | 151 | 20.5 | 22 |

| Hydrophobic interaction chromatography | 20 | 41.5 | 123 | 25.9 | 18 |

| Size-exclusion chromatography | 20 | 68.8 | 93 | 43 | 13 |

Standard errors for data are below 4%.

Properties of feruloyl esterase.

SDS-PAGE analysis of the A. pullulans feruloyl esterase gave a single band with an estimated molecular mass of 210 kDa. The same molecular mass was obtained by gel filtration chromatography, suggesting that the enzyme consists of a single monomer with a high Mr. The purified enzyme also showed a single band after isoelectric focusing which corresponded to a pI of 6.5. Enzymatic deglycosylation of the feruloyl esterase and subsequent SDS-PAGE and gel filtration gave a protein with an apparent molecular mass of 110 kDa, suggesting that the A. pullulans feruloyl esterase is 48% glycosylated. The enzyme proved to be stable in conjunction with other proteins. The crude culture filtrate preserved 80% of its initial activity after 6 months at 4°C, whereas the half-life of feruloyl esterase after anion-exchange chromatography or of pure feruloyl esterase was only 1 month at 4°C. Pure feruloyl esterase exhibited maximum activity between 60 and 65°C in a 10-min assay with NPh-5-Fe-Araf or NPh-2-Fe-Araf as substrate (data not shown), and at the standard assay temperature of 30°C it showed 79% of maximum activity. With the same substrates, feruloyl esterase exhibited 100% activity at a pH of 6.7 and only 50% at pHs 4 and 8.5.

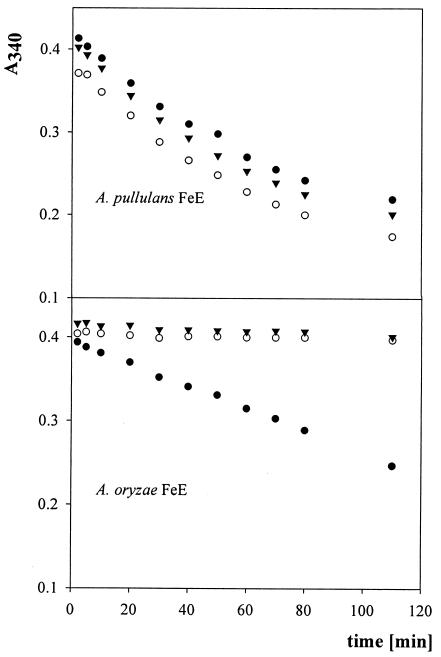

Substrate specificity of A. pullulans feruloyl esterase compared to that of A. oryzae feruloyl esterase.

A. oryzae feruloyl esterase hydrolyzes NPh-5-Fe-Araf, but NPh-2-Fe-Araf and NPh-4-Fe-Xylp are hardly hydrolyzed whereas the A. pullulans feruloyl esterase hydrolyzes all three substrates at about the same rate (Fig. 2). The absorbance decrease with A. oryzae feruloyl esterase was almost linear, suggesting lower Km values than those for the A. pullulans feruloyl esterase.

FIG. 2.

Comparison of hydrolysis of different substrates by A. pullulans feruloyl esterase and A. oryzae feruloyl esterase. Symbols: •, NPh-5-Fe-Araf; ▾, NPh-4-Fe-Xylp; ○, NPh-2-Fe-Araf.

A summary of kinetic data for A. pullulans feruloyl esterase on a variety of substrates is presented in Table 2. The enzyme catalyzed the hydrolysis of all tested methyl cinnamates with the activity for MpCA being highest followed by those for MCA, MFA, and MSA. Similarly, catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) calculations revealed a value 10-fold greater for MpCA than for the other methyl cinnamate substrates. Compared to methyl cinnamates, feruloyl esterase showed greater activity with NPh-5-Fe-Araf, NPh-2-Fe-Araf, and NPh-4-Fe-Xylp as substrates. Furthermore the substrate turnover rate (kcat) was greater with NPh-5-Fe-Araf and NPh-2-Fe-Araf although the substrate affinity (Km) was lower. Feruloyl esterase also hydrolyzed FAXX and 4-nitrophenyl-acetate but showed almost no activity for 4-nitrophenyl-butyrate. The kcat/Km catalytic efficiency values were similar for most substrates, although the constant was much greater for MpCA, suggesting that the chemical structure of the phenolic moiety of the substrate is essential for the catalysis by feruloyl esterase.

TABLE 2.

Substrate specificities for A. pullulans feruloyl esterasea

| Substrate | Sp act (μmol/min/mg) | Km (μM) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/Km (s−1 M−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MFA | 21.6 (0.7) | 50.2 (0.9) | 15.3 (0.5) | 0.3 × 106 |

| MpCA | 35.3 (0.5) | 10.6 (0.2) | 31.1 (0.3) | 2.9 × 106 |

| MSA | 12.9 (0.9) | 137 (11) | 23.7 (0.5) | 0.17 × 106 |

| MCA | 30.4 (0.5) | 98 (8) | 30 (0.9) | 0.3 × 106 |

| NPh-5-Fe-Araf | 74.6 (1) | 268 (13) | 65.5 (1) | 0.24 × 106 |

| NPh-2-Fe-Araf | 71.1 (0.9) | 230 (13) | 70.2 (0.9) | 0.3 × 106 |

| NPh-4-Fe-Xylp | 73.2 (0.9) | NDb | ND | ND |

| FAXX | 35.9 (1.2) | ND | ND | ND |

| 4-Nitrophenyl-acetate | 31.8 (0.2) | ND | ND | ND |

| 4-Nitrophenyl-butyrate | 0.02 (0.01) | ND | ND | ND |

Numbers in parentheses are estimates of the standard errors.

ND, not determined.

Protein sequencing.

The first eight residues of the N-terminal amino acid sequence of the A. pullulans feruloyl esterase (AVYTLDGD) were determined, but subsequent residues could not be ascertained. A BLAST search using the N-terminal sequence of A. pullulans feruloyl esterase revealed no similarities to other known N-terminal regions of feruloyl esterases.

DISCUSSION

The extracellular feruloyl esterase from A. pullulans, with an apparent molecular mass of 210 kDa, is the largest single-subunit enzyme of its kind. Taking into account 48% of Asp-linked glycosylation, the deglycosylated enzyme is in the size range of Aspergillus niger (23) and Aspergillus awamori (28) feruloyl esterases but is still much larger than feruloyl esterases from other fungi such as Penicillium species (6, 13, 24) and Neocallimastix species (3). The reason for the high degree of glycosylation is unclear, although A. pullulans produces significant amounts of the exopolysaccharide pullulan (11), and other hemicellulolytic enzymes (xylanase, xylosidase, and α-glucuronidase) from this organism have also been found to be heavily glycosylated when estimated by SDS-PAGE (B. J. M. de Wet and J. Myburgh, unpublished data). The pI of 6.5 and maximum activity at pH 6.7 indicate that these properties of A. pullulans feruloyl esterase are slightly above values reported for other fungal feruloyl esterases, which typically show pIs between 3 and 4.5 and maximum activities at pH values between 5 and 6 (39). The maximum temperature for feruloyl esterase activity of 60°C is consistent with that observed for β-glucosidase (35) and α-l-arabinofuranosidase (34) of A. pullulans.

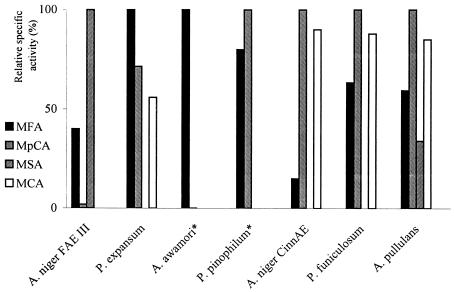

Various cinnamic acid methyl esters have been used to evaluate the specificity of feruloyl esterase for the phenolic moiety of its substrate. A. pullulans feruloyl esterase shows the highest specific activity for MpCA but little difference in selectivity for the other substrates compared to fungal feruloyl esterases. MSA, for example, is a very poor substrate for A. niger CinnAE (23), Penicillium expansum (13), and Penicillium funiculosum (24) feruloyl esterases, whereas A. niger FAE III (15) shows no activity on MCA. However, the order MpCA > MCA > MFA > MSA observed for A. pullulans feruloyl esterase is analogous to the order reported for A. niger CinnAE, P. funiculosum, and Penicillium pinophilum (6) feruloyl esterases (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Comparison of the substrate specificities of fungal feruloyl esterases from A. niger FAE III (15), P. expansum (13), A. awamori (26), P. pinophilum (6), A. niger CinnAE (23), P. funiculosum (24), and A. pullulans (this study). *, MSA and MCA activities have not been determined.

The specificity of feruloyl esterases for the sugar moiety of the substrate was investigated using synthetic substrates that have a feruloyl group attached to either the C-2 or the C-5 position of arabinofuranose, similar to naturally occurring compounds. So far, feruloyl esterases can be divided into two classes based on their activity for either only C-5 or C-5 and C-2 ferulated substrates. Among fungal enzymes that have been examined, A. pullulans feruloyl esterase belongs to the latter, together with A. niger CinnAE (23) and P. funiculosum FAEB (24), whereas A. niger FAE III (15) and A. oryzae feruloyl esterase (38) are members of the first class. Feruloyl esterases that catalyze exclusively C-2 ferulated arabinofuranosides have not been described to date.

The nature of feruloyl esterase specificity, for both the phenolic and the sugar moieties, remains to be elucidated. Too few enzymes have been isolated, and characterization data are mostly not uniform. However, A. pullulans feruloyl esterase could be classified according to available data and shows properties similar to those for other fungal feruloyl esterases, especially A. niger CinnAE (23) and P. funiculosum FAEB (24). The N-terminal sequence of A. pullulans feruloyl esterase was reliably identified, but the sequencing reaction was prematurely terminated possibly due to the presence of a proline that is cleaved less efficiently (R. van Wyk, personal communication). A BLAST search failed to reveal significant similarity to known feruloyl esterases or to carbohydrate esterases in general. However, a search based on eight N-terminal amino acids is generally too limited to establish similarity, and furthermore the N-terminal regions of feruloyl esterases are apparently poorly conserved (40).

Acknowledgments

We thank Craig Faulds (Institute for Food Research, Norwich, United Kingdom) for providing us with various methyl cinnamates and FAXX and Maija Tenkanen (VTT, Espoo, Finland) for the A. oryzae feruloyl esterase. René van Wyk (Molecular Biology Unit, University of Natal, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa) is thanked for N-terminal sequencing of feruloyl esterase.

We acknowledge the Austrian Bundesministerium für Bildung, Wissenschaft und Kultur, Postgraduate Stipendium GZ 14.910, and the South African National Research Foundation for financial support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Biely, P., M. Mastihubová, W. H. van Zyl, and B. A. Prior. 2002. Differentiation of feruloyl esterases on synthetic substrates in α-arabinofuranosidase-coupled and UV-spectrophotometric assays. Anal. Biochem. 311:68-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blum, D. L., I. A. Kataeva, X. L. Li, and L. G. Ljungdahl. 2000. Feruloyl esterase activity of the Clostridium thermocellum cellulosome can be attributed to previously unknown domains of XynY and XynZ. J. Bacteriol. 182:1346-1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borneman, W. S., L. G. Ljungdahl, R. D. Hartley, and D. E. Akin. 1992. Purification and partial characterization of two feruloyl esterases from the anaerobic fungus Neocallimastix strain MC-2. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:3762-3766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boudet, A. M. 2000. Lignins and lignification: selected issues. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 38:81-96. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castanares, A., S. I. McCrae, and T. M. Wood. 1992. Purification and properties of a feruloyl/p-coumaroyl esterase from the fungus Penicillium pinophilum. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 14:875-884. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christov, L. P., and B. A. Prior. 1996. Repeated treatments with Aureobasidium pullulans hemicellulases and alkali enhance biobleaching of sulphite pulps. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 18:244-250. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cornu, A., J. M. Besle, P. Mosoni, and G. G. Gross. 1994. Lignin-carbohydrate complexes in forages: structure and consequences in the ruminal degradation of cell-wall carbohydrates. Reprod. Nutr. 34:385-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coutinho, P. M., and B. Henrissat. 1999. Carbohydrate-active enzymes: an integrated database approach, p. 3-12. In H. J. Gilbert, G. Davies, B. Henrissat, and B. Svensson (ed.), Recent advances in carbohydrate bioengineering. The Royal Society of Chemistry, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

- 10.Dalrymple, B. P., Y. Swadling, D. H. Cybinski, and G. P. Xue. 1996. Cloning of a gene encoding cinnamoyl ester hydrolase from the ruminal bacterium Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens E14 by a novel method. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 143:115-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deshpande, M. S., V. B. Rale, and J. M. Lynch. 1992. Aureobasidium pullulans in applied microbiology: a status report. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 14:514-527. [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Vries, R. P., B. Michelsen, C. H. Poulsen, P. A. Kroon, R. H. van den Heuvel, C. B. Faulds, G. Williamson, J. P. van den Hombergh, and J. Visser. 1997. The faeA genes from Aspergillus niger and Aspergillus tubingensis encode ferulic acid esterases involved in degradation of complex cell wall polysaccharides. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:4638-4644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donaghy, J., and A. M. McKay. 1997. Purification and characterization of a feruloyl esterase from the fungus Penicillium expansum. J. Appl. Microbiol. 83:718-726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faulds, C. B., and G. Williamson. 1991. The purification and characterization of 4-hydroxy-3-methoxycinnamic (ferulic) acid esterase from Streptomyces olivochromogenes. J. Gen. Microbiol. 137:2339-2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faulds, C. B., and G. Williamson. 1994. Purification and characterization of a ferulic acid esterase (FAE-III) from Aspergillus niger: specificity of the phenolic moiety and binding to microcrystalline cellulose. Microbiology 140:779-787. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fillingham, I. J., P. A. Kroon, G. Williamson, H. J. Gilbert, and G. P. Hazlewood. 1999. A modular cinnamoyl ester hydrolase from the anaerobic fungus Piromyces equi acts synergistically with xylanase and is part of a multiprotein cellulose-binding cellulase-hemicellulase complex. Biochem. J. 343:215-224. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fry, S. C. 1986. Cross-linking of matrix polymers in the growing cell walls of angiosperms. Annu. Rev. Plant. Physiol. 37:165-186. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gübitz, G. M., D. W. Stebbing, C. I. Johansson, and J. N. Saddler. 1998. Lignin-hemicellulose complexes restrict enzymatic solubilization of mannan and xylan from dissolving pulp. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 50:390-395. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gudelj, M., G. Valinger, K. Faber, and H. Schwab. 1998. Novel Rhodococcus esterases by genetic engineering. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 5:261-266. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iiyama, K., T. B. T. Lam, and B. A. Stone. 1990. Phenolic bridges between polysaccharides and lignin in wheat internodes. Phytochemistry 29:733-737. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ishii, T., T. Hiroi, and J. R. Thomas. 1990. Feruloylated xyloglucan and p-coumaryl arabinoxylan oligosaccharides from bamboo shoot cell walls. Phytochemistry 29:1999-2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jeffries, T. W. 1990. Biodegradation of lignin-carbohydrate complexes. Biodegradation 1:163-176. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kroon, P. A., C. B. Faulds, and G. Williamson. 1996. Purification and characterization of a novel esterase induced by growth of Aspergillus niger on sugar-beet pulp. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 23:255-262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kroon, P. A., G. Williamson, N. M. Fish, D. B. Archer, and N. J. Belshaw. 2000. A modular esterase from Penicillium funiculosum which releases ferulic acid from plant cell walls and binds crystalline cellulose contains a carbohydrate binding module. Eur. J. Biochem. 267:6740-6752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lam, T. B. T., K. Kadoya, and K. Iiyama. 2001. Bonding of hydroxycinnamic acids to lignin: ferulic and p-coumaric acids are predominantly linked at the benzyl position of lignin, not the β-position, in grass cell walls. Phytochemistry 57:987-992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leathers, T. D. 1986. Color variants of Aureobasidium pullulans overproduce xylanase with extremely high specific activity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 52:1026-1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCrae, S. I., K. M. Leith, A. H. Gordon, and T. M. Wood. 1994. Xylan-degrading enzyme system produced by the fungus Aspergillus awamori: isolation and characterization of a feruloyl esterase and a p-coumaroyl esterase. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 16:826-834. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prates, J. A. M., N. Tarbouriech, S. J. Charnock, C. M. G. A. Fontes, L. M. A. Ferreira, and G. J. Davies. 2001. The structure of the feruloyl esterase module of xylanase 10B from Clostridium thermocellum provides insights into substrate recognition. Structure 9:1183-1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ralph, J., R. F. Helm, S. Quideau, and R. D. Hatfield. 1992. Lignin-feruloyl ester cross links in grasses. Part 1. Incorporation of feruloyl esters into coniferyl alcohol dehydrogenation polymers. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. I 21:2961-2969. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reid, J. G. 2000. Cementing the wall: cell wall polysaccharide synthesising enzymes. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 3:512-516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rumbold, K., G. M. Gübitz, K.-H. Robra, and B. A. Prior. 2002. Influence of growth substrate and free ferulic acid on the production of feruloyl esterase by Aureobasidium pullulans, p. 151-160. In S. D. Mansfield and J. N. Saddler (ed.), Enzymes in lignocellulose degradation. American Chemical Society, Washington, D.C.

- 33.Rumbold, K., H. Okatch, N. Torto, M. Siika-Aho, G. M. Gübitz, K.-H. Robra, and B. A. Prior. 2002. Monitoring on-line desalted lignocellulosic hydrolysates by microdialysis sampling micro-high performance anion exchange chromatography with integrated pulsed electrochemical detection/mass spectrometry. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 78:822-828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saha, B. C., and R. J. Bothast. 1998. Purification and characterization of a novel thermostable α-l-arabinofuranosidase from a color-variant strain of Aureobasidium pullulans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:216-220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saha, B. C., S. N. Freer, and R. J. Bothast. 1994. Production, purification and properties of a thermostable β-glucosidase from a color-variant strain of Aureobasidium pullulans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:3774-3780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sancho, A. I., C. B. Faulds, B. Bartolome, and G. Williamson. 1999. Characterisation of feruloyl esterase activity in barley. J. Sci. Food Agric. 79:447-449. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saulnier, L., and J. F. Thibault. 1999. Ferulic acid and diferulic acids as components of sugar-beet pectins and maize bran heteroxylans. J. Sci. Food Agric. 79:396-402. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tenkanen, M., J. Schuseil, J. Puls, and K. Poutanen. 1991. Production, purification and characterization of an esterase liberating phenolic acids from lignocellulosics. J. Biotechnol. 1:69-84. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Williamson, G., C. B. Faulds, and P. A. Kroon. 1998. Specificity of ferulic acid (feruloyl) esterases. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 26:205-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Williamson, G., P. A. Kroon, and C. B. Faulds. 1998. Hairy plant polysaccharides: a close shave with microbial esterases. Microbiology 144:2011-2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]