Abstract

The role of mannose-sensitive hemagglutinin (MSHA) in Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor interactions with hemolymph of the mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis was studied. Bacterial adherence to and association with hemocytes were evaluated at 4 and 18°C, respectively. In hemolymph serum, the wild-type strain N16961 adhered to and associated with hemocytes about twofold more efficiently than its mutant lacking MSHA. In artificial seawater (ASW), no significant differences between the two strains were observed. N16961 was also more sensitive to hemocyte bactericidal activity than its MSHA mutant; in fact, the percentages of killed bacteria after 120 min of incubation were 60 and 34%, respectively. The addition of d-mannose abolished the serum-mediated increase in adherence, association, and sensitivity to killing of the wild-type strain without affecting the interactions of the mutant. A similar increase in N16961 adherence to hemocytes was observed when serum was adsorbed with MSHA-deficient bacteria. In contrast, serum adsorbed with either wild-type V. cholerae El Tor or wild-type Escherichia coli carrying type 1 fimbriae was no longer able to increase adherence of N16961 to hemocytes. The results indicate that hemolymph-soluble factors are involved in interactions between hemocytes and mannose-sensitive adhesins.

Vibrio cholerae is an important pathogen that causes the waterborne diarrheal disease cholera; two serogroups, O1 and O139, have been associated with the epidemic syndrome (21). It is now well known that toxinogenic V. cholerae strains are part of the autochtonous bacterial flora in estuarine areas where they can persist in the absence of human inputs. The survival of this microorganism within the aquatic environment is facilitated by its ability to adopt multiple survival strategies (7-9), including biofilm formation on biotic and abiotic substrates (6, 17, 18, 32, 33).

Many works have recently dealt with the mechanisms by which V. cholerae adheres to different surfaces inside and outside the human host. In general, the adhesive process appears to be multifactorial, with contributions from a variety of different cell surface and secreted components. Concerning interactions with intestinal epithelial cells, toxin-coregulated pilus (TCP) seems to be an essential adhesion factor (1, 21, 28). In the aquatic environment, membrane proteins were shown to play a role in the attachment of V. cholerae O1 classical strains to chitin-containing substrates (29). Recently, the type IV pilus, mannose-sensitive hemagglutinin (MSHA), which is present in strains of either El Tor biotype or O139 serogroup (20, 28), has been implicated in biofilm formation by El Tor vibrios on nonnutritive, abiotic surfaces (32, 33) and adherence of El Tor and O139 bacteria to zooplankton exoskeleton (6).

During their persistence in seawater, vibrios as well as other indigenous and nonindigenous bacteria can be entrapped by filter-feeding invertebrates that sieve suspended food particles from the aquatic environment. In particular, edible bivalves (such as mussels, clams, and oysters) can accumulate large amounts of bacteria in their tissues and may act as passive carriers of human pathogens. Persistence of bacteria in bivalves as well as in other shellfish largely depends on their sensitivity to the hemolymph bactericidal activity (10, 11, 16, 23, 24, 30). Bivalve hemolymph contains both hemocytes, which are responsible for cellular defense mechanisms (i.e., phagocytosis, production of reactive oxygen intermediates, and release of lysosomal enzymes), and humoral defense factors such as opsonins and hydrolytic enzymes (23, 26, 31). Bacteria show different capacities to survive to hemocyte phagocytosis as a consequence of the different ability to attract phagocytes, to interact with opsonizing molecules, to bind hemocytes, and to survive intracellular killing (reviewed in reference 3). At present, data on the role played by bacterial surface components in both favoring and inhibiting the above processes are scanty (3, 4, 16).

Elucidation of the molecular mechanisms by which V. cholerae interacts with the immune system of bivalves is of great importance for a better comprehension of both its survival strategies in the aquatic environment and its transmission to humans through consumption of raw or lightly cooked bivalves. In this light, we investigated whether bacterial surface components, such as MSHA and TCP, might be involved in the interactions of V. cholerae O1 El Tor with the hemolymph of the Mediterranean mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis Lam.

The V. cholerae strains used in this study were serogroup O1 El Tor biotype strain N16961 and its MSHA and TCP mutants (32), kindly provided by R. Kolter. V. cholerae El Tor strain identification was confirmed by biochemical tests (13) with the API20E identification system (API System S. A., Monalieu-Vercieu, France) and a direct fluorescent-monoclonal antibody staining kit specific for V. cholerae O1 (New Horizons Diagnostics Corporation, Columbia, Md.); detection of MSHA activity was performed by using chicken erythrocytes as described previously (25). Escherichia coli MG1655 (CGSC6300) (15) carrying type 1 fimbriae and the unfimbriated derivative AAEC072 Δfim (2) were also used. The presence of type 1 fimbriae in MG1655 was confirmed by both bacterial ability to cause d-mannose-sensitive agglutination of yeast cells (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) (14) and electron microscopy analysis of negatively stained bacterial preparations (12). All cultures were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth or agar (27) under static conditions at 37°C.

To radiolabel bacteria, strains were grown overnight in LB broth containing 10 μCi of [methyl-3H]thymidine (25 Ci/mmol) ml−1. Cells were then harvested by centrifugation (3,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C), washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 0.1 M KH2PO4, 0.1 M Na2HPO4, 0.15 M NaCl, pH 7.2 to 7.4), and resuspended in PBS at an A650 of 1 (2 × 109 to 4 × 109 CFU ml−1). The number of counts per minute (cpm) per milliliter and the number of CFU per milliliter were evaluated to calculate the efficiency of cell labeling (number of CFU per cpm) that varied in different bacterial preparations from 150 to 300. Artificial seawater (ASW) prepared following the methods of La Roche et al. (22), 35 ‰ (wt/vol) salinity, pH 7.9, and filtered onto 0.22-μm-pore-size Millipore filters (Bedford, Mass.) was used throughout the experiments.

Mussels (M. galloprovincialis Lam) were obtained from the depuration plant Casa del Pescatore (Cattolica, Italy) during the spring of 2002. Average monthly temperature and salinity at the collection site were 15°C and 35‰, respectively. Mussels were transferred to the laboratory, gently scrubbed to remove epibiota, moistened with 100% ethanol to sterilize the surface, and kept in an aquarium at 16°C in static tanks containing ASW (1 liter/animal) for 1 to 3 days before use; seawater was changed daily. Hemolymph extraction, preparation of hemolymph serum (i.e., hemolymph free of cells), determination of hemocyte concentration, and preparation of hemocyte monolayers on coverslips were as previously described (4, 5).

Bacterial adherence to and association with hemocytes were evaluated as previously described (4). Briefly, aliquots (1.5 ml) of either ASW or hemolymph serum containing radiolabeled bacteria at the final concentration of about 107 CFU ml−1 were added to monolayers on coverslips contained in plastic culture dishes (hemocytes/bacteria ratio, about 1:10); the dishes were then incubated with gentle shaking at either 18°C (to evaluate all associated bacteria, i.e., attached plus internalized) or 4°C (to evaluate attached bacteria only). Bacterial binding to hemocytes was also evaluated at 18°C after 30 min of treatment of hemocyte monolayers with cytochalasin D (CD) at a final concentration of 5 μg ml−1. Triplicate preparations were made for each sample. After 120 min of incubation the coverslips were rinsed three times with 3 ml of cold ASW to remove nonadherent bacteria and were transferred to PICO-FLUOR15 scintillation fluid (Packard Instruments Company Inc., Meriden, Conn.). The number of cpm per coverslip was evaluated by using a Beckman L5 1801 scintillation counter. For each sample the number of bacteria per monolayer was calculated by multiplying the cpm values by the efficiency of cell labeling. Values obtained by this method included both live bacteria and those killed by the hemolymph. Background counts due to bacterial attachment to coverslips were determined as previously described (4).

To evaluate bacterial sensitivity to killing by hemocytes, V. cholerae suspensions (about 107 CFU ml−1) were added to hemocyte monolayers at 18°C in the presence of hemolymph serum as described above. Triplicate preparations were made for each sampling time. Immediately after the inoculum (T = 0) and after 60 and 120 min of incubation at 18°C supernatants were collected from monolayers, and hemocytes were lysed by adding 5 ml of cold distilled water and by 10 min of agitation. The collected monolayer supernatants and hemocyte lysates were pooled and tenfold serial diluted in PBS; aliquots (100 μl) of the diluted samples were plated onto LB agar, and after overnight incubation at 37°C the number of CFU per milliliter in the hemocyte monolayer (representing culturable bacteria survived to hemocyte bactericidal activity) was determined. Percentages of killing at 60 and 120 min were then determined relative to values obtained at T = 0. To evaluate the presence of endogenous bacteria in hemocytes, controls were performed with hemocyte monolayers without bacteria. The number of CFU in controls never exceeded 0.1% of those enumerated in experimental samples. To detect and correct for bacterial growth in hemolymph serum, separate samples were seeded with bacteria and 1.5 ml of sterile hemolymph serum. No appreciable bacterial growth was observed at the same time intervals used in killing experiments. All the experiments were also performed in the presence of d-mannose and d-galactose at a final concentration ranging from 1 to 30 mg ml−1. Adsorbed hemolymph serum was obtained as previously described (4).

Data, representing the mean of at least three separate trials in triplicate, were analyzed for significance by the Mann-Whitney U test. Differences were considered significant at P ≤ 0.05.

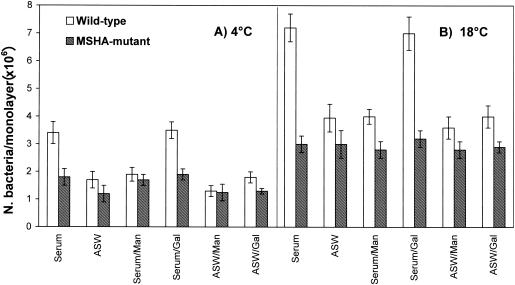

The contribution of MSHA and TCP in V. cholerae O1 El Tor interactions with Mytilus hemocytes was studied by comparing wild-type strain N16961's ability to adhere to hemocytes with that of its mutants lacking either MSHA or TCP. Experiments were performed in conditions that inhibit the internalization process, at either 4 or 18°C, by using CD (4). Since similar results were obtained in both conditions, only data at 4°C are reported below. The results demonstrate (Fig. 1A) that in the presence of serum at 4°C, the wild-type strain adhered to hemocytes with an efficiency that was about twofold higher than that of its MSHA-deficient derivative (P < 0.01). In ASW a lower, not significant difference (1.4-fold) between the two strains was observed. This indicates that serum-soluble factors able to bind MSHA may play a role in promoting vibrio-hemocyte interactions. On the other hand, no differences were observed between N16961 and its TCP mutant, even when bacteria were grown in AKI medium to maximize TCP expression (19) (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Role of MSHA in interactions between V. cholerae El Tor and mussel hemocytes in both hemolymph serum and ASW. Adherence and association of the V. cholerae wild-type strain (N16961) and its MSHA mutant were evaluated at 4°C (A) and 18°C (B) in the presence or in the absence of d-mannose (Man) and d-galactose (Gal) (30 mg ml−1). Bars indicate standard deviations.

To clarify to what extent the observed differences in adhesion may lead to differences in association, the interactions with hemocytes of the wild-type V. cholerae El Tor strain and its MSHA-deficient mutant were analyzed at 18°C (Fig. 1B). The results demonstrated that bacteria that express the MSHA associate with hemocyte monolayers in the presence of serum with an efficiency 2.4-fold higher than that of the mutant (P < 0.01). In ASW a smaller and not significant difference (1.3-fold) in association was observed between the two strains.

The same experiments were performed in the presence of d-mannose; in fact, MSHA mediates binding to d-mannose-containing receptors (20). The addition of d-mannose (30 mg ml−1) almost abolished the serum-mediated increase in both adherence at 4°C and association at 18°C of the wild-type strain without affecting the interactions of the mutant strain (Fig. 1A and B). On the other hand, in ASW d-mannose did not significantly affect the interactions with hemocytes of either strain at any temperature (Fig. 1A and B). d-galactose did not have any effect on the interactions of either strain with hemocytes in both serum and ASW.

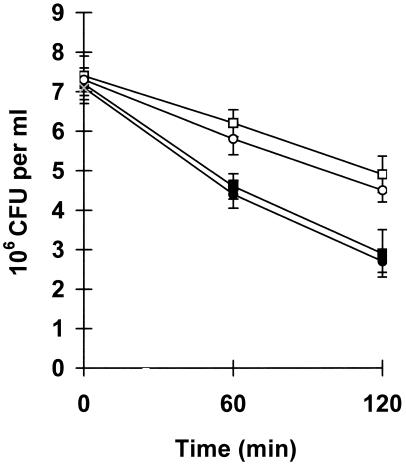

Wild-type V. cholerae was more sensitive than the mutant to in vitro killing by hemocyte monolayers (Fig. 2). In fact, after 60 and 120 min of incubation, the percentage of killed bacteria compared to that at T = 0 was about 36 and 60% for the wild-type strain and about 16 and 34% for its derivative, respectively. All differences between the two strains were statistically significant (P ≤ 0.05) and were abolished by addition of d-mannose (Fig. 2) but not of d-galactose.

FIG. 2.

Survival of V. cholerae wild-type strain (N16961) and its MSHA mutant in hemocyte monolayers in vitro. Results are expressed as the number of culturable bacteria per milliliter in the hemocyte monolayer. Symbols: ▪, wild type; □, MSHA mutant; ○, wild type plus d-mannose; •, wild type plus d-galactose. Bars indicate standard deviations.

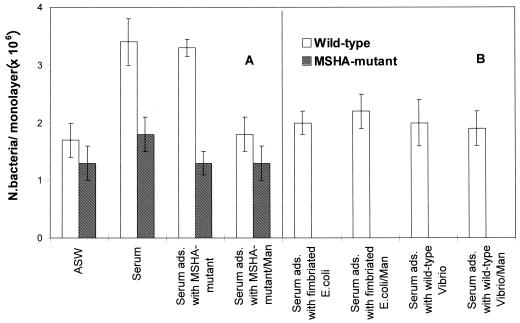

The presence in serum of MSHA-binding-soluble factors was shown in experiments where hemolymph serum was adsorbed with MSHA-deficient bacteria to remove agglutinins common to both strains and then tested for its ability to affect wild-type strain adherence to the hemocytes. The adsorbed serum, like the unadsorbed one, caused a twofold increase (P < 0.05) in N16961 adherence to hemocyte monolayers at 4°C compared to that of ASW; this effect was completely inhibited by d-mannose (Fig. 3A). In contrast, the adsorbed serum did not affect adherence of the MSHA mutant to hemocytes with respect to ASW.

FIG. 3.

V. cholerae El Tor adherence to M. galloprovincialis hemocytes in serum adsorbed with MSHA mutant (A) and in serum adsorbed with either wild-type V. cholerae or wild-type E. coli (B). Adherence was evaluated at 4°C in the presence or in the absence of d-mannose (Man) (30 mg ml−1). ads., adsorbed. Bars indicate standard deviations.

It was previously shown that mussel hemolymph serum contains soluble factors that are involved in d-mannose-sensitive interactions between E. coli carrying type 1 fimbriae and hemocytes (4). The results obtained with V. cholerae carrying MSHA suggest that hemolymph serum may contain broad-spectrum opsonizing molecules able to bind both MSHA and type 1 fimbriae. To investigate this possibility, two different aliquots of hemolymph serum were adsorbed with either fimbriated E. coli (MG1655) or V. cholerae carrying MSHA (N16961), respectively, to remove d-mannose-sensitive serum factors directed towards either strain. As shown in Fig. 3B, serum adsorbed with either wild-type V. cholerae or wild-type E. coli was no longer able to increase adherence of the wild-type N16961 to hemocytes. Moreover, in the presence of adsorbed sera, the interactions with hemocytes were no longer d-mannose sensitive. These data indicate that a soluble hemolymph fraction is able to bind bacterial ligands that share the property of mediating d-mannose-sensitive interactions and support the hypothesis that, to recognize heterogeneous bacterial surface components, mussels might utilize a limited number of molecules with a broad spectrum of specificity and binding capability.

Overall, our data indicate that MSHA promotes interactions between V. cholerae El Tor and hemolymph and leads to an enhanced sensitivity to hemolymph microbicidal activity. These results confirm those of previous studies indicating that MSHA pilus is an important mediator of vibrio interactions with different substrates in the aquatic environment; in fact, it would play not only a role in attachment to abiotic surfaces (zooplankton exoskeleton) (6) and to nonnutritive substrates (32, 33) but also in opsonin-dependent adherence to living cells (bivalve hemocytes). Further studies are needed to evaluate the expression of MSHA by vibrios isolated from mussel tissues, the influence of physical and chemical conditions in vibrio-hemocyte interactions, and the role of MSHA in vibrio adherence to other mussel cell types. This information will be crucial to better understand the strategies used by V. cholerae to persist within bivalve tissues and, in general, in the aquatic environment.

Acknowledgments

We are greatly indebted to R. Kolter and P. I. Watnick for providing us with the V. cholerae strains. Special thanks to Gerardo Vasta for his helpful suggestions.

This work was supported by Ministero Salute “Ricerca Finalizzata 1999,” CNR Target Project on Biotechnology 99.00448.PF49, and MURST COFIN 2000.

REFERENCES

- 1.Attridge, S. R., P. A. Manning, J. Holmgren, and G. Jonson. 1996. Relative significance of mannose-sensitive hemagglutinin and toxin-coregulated pili in colonization of infant mice by Vibrio cholerae El Tor. Infect. Immun. 64:3369-3373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blomfield, I. C., M. S. Clain, and B. I. Eisenstein. 1991. Type 1 fimbriae mutants of Escherichia coli K12: characterization of recognized afimbriated strains and construction of new mutants. Mol. Microbiol. 5:1439-1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canesi, L., G. Gallo, M. Gavioli, and C. Pruzzo. 2002. Bacteria-hemocyte interactions and phagocytosis in marine bivalve. Microsc. Res. Tech. 57:469-476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canesi, L., C. Pruzzo, R. Tarsi, and G. Gallo. 2001. Surface interactions between Escherichia coli and hemocytes of the Mediterranean mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis Lam leading to efficient bacterial clearance. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:464-468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen, J. H., and C. J. Bayne. 1994. The roles of carbohydrates in aggregation and adhesion of hemocytes from the California mussel (Mytilus californianus) Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 109A:117-125. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiavelli, D. A., J. W. Marsh, and R. K. Taylor. 2001. The mannose-sensitive hemagglutinin of Vibrio cholerae promotes adherence to zooplankton. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:3220-3225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colwell, R. R. 1996. Global climate and infectious disease: the cholera paradigm. Science 274:2025-2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colwell, R. R. 2000. Bacterial death revisited, p. 325-342. In R. R. Colwell and D. J. Grimes (ed.), Nonculturable microorganisms in the environment. American Society for Microbiology Press, Washington, D.C.

- 9.Colwell, R. R., P. R. Brayton, A. Huq, B. Tall, P. Harrington, and M. Levine. 1996. Viable but non-culturable Vibrio cholerae O1 revert to a culturable state in the human intestine. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 12:28-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cuthbertson, B. J., E. F. Shepard, R. W. Chapman, and P. S. Gross. 2002. Diversity of the penaeidin antimicrobial peptides in two shrimp species. Immunogenetics 54:442-445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Destoumieux, D., M. Munoz, P. Bulet, and E. Bachere. 2000. Penaeidins, a family of antimicrobial peptides from penaeid shrimp (Crustacea, Decapoda). Cell Mol. Life Sci. 57:1260-1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eshdat, Y., V. Speth, and K. Jann. 1981. Participation of pili and cell wall adhesin in the yeast agglutination activity of Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 34:980-986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farmer, J. J., III, F. W. Hickman-Brenner, and M. T. Kelly. 1991. Vibrio, p. 281-301. In E. H. Lennette, A. Balows, W. J. Hausler, and H. J. Shadomy (ed.), Manual of clinical microbiology, 4th ed. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 14.Firon, N., S. Ashkenazi, D. Mirelman, I. Ofek, and N. Sharon. 1987. Aromatic alpha-glycosides of mannose are powerful inhibitors of the adherence of type 1 fimbriated Escherichia coli to yeast and intestinal epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 55:472-476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guyer, M. S., R. R. Reed, J. A. Steitz, and K. B. Low. 1980. Identification of a sex-factor-affinity site in E. coli gd. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 45:135-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harris-Young, L., M. L. Tamplin, W. J. Mason, H. C. Aldrich, and K. Jackson. 1995. Viability of Vibrio vulnificus in association with hemocytes of the American oyster (Crassostrea virginica). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:52-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hood, M. A., and P. A. Winter. 1997. Attachment of Vibrio cholerae under various environmental conditions and to selected substrates. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 22:215-223. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huq, A., P. A. West, E. B. Small, M. I. Huq, and R. R. Colwell. 1984. Influence of water temperature, salinity, and pH on survival and growth of toxigenic Vibrio cholerae serovar O1 associated with live copepods in laboratory microcosms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 48:420-424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iwanaga, M., K. Yamamoto, N. Higa, Y. Ichinose, N. Nakasone, and M. Tanabe. 1986. Culture conditions for stimulating cholera toxin production by Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor. Microb. Immunol. 30:1075-1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jonson, G., M. Lebens, and J. Holmgren. 1994. Cloning and sequencing of Vibrio cholerae mannose-sensitive hemagglutinin pilin gene localization of mshA within a cluster of type 4 pilin genes. Mol. Microbiol. 13:109-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaper, J. B., G. J. Morris, and M. M. Levine. 1995. Cholera. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 8:48-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.La Roche, G., R. Eisler, and C. Tarzwell. 1970. Bioassay procedures for oil dispersal toxicity evaluation. J. Water Pollut. Control Fed. 42:1982-1988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olafsen, J. A. 1995. Role of lectins (C-reactive protein) in defense of marine bivalves against bacteria, p. 343-348. In J. Mesteeky, M. W. Russell, S. Jackson, S. M. Michalek, H. Tlaskalová-Hogenová, and J. ˘Sterzl (ed.), Advances in mucosal immunology. Plenum Press, New York, N.Y. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Prieur, D., G. Mevel, J. L. Nicolas, A. Plusquellec, and M. Vigneulle. 1990. Interactions between bivalve mollusks and bacteria in the marine environment. Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. Annu. Rev. 28:277-352. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qadri, F., G. Jonson, Y. A. Begum, C. Wenneras, M. J. Albert, M. A. Salam, and A. M. Svennerrholm. 1997. Immune response to the mannose-sensitive hemagglutinin in patients with cholera due to Vibio cholerae O1 and O139. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 4:429-434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Renwranz, L. 1990. Internal defence system of Mytilus edulis, p. 256-275. In G. B. Stefano (ed.), Neurobiology of Mytilus edulis. Manchester University Press, Manchester, United Kingdom.

- 27.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 28.Tacket, C. O., R. K. Taylor, G. Losonsky, Y. Lim, J. P. Nataro, J. B. Kaper, and M. M. Levine. 1998. Investigation of the roles of toxin-coregulated pili and mannose-sensitive hemagglutinin pili in the pathogenesis of Vibrio cholerae O139 infection. Infect. Immun. 66:692-695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tarsi, R., and C. Pruzzo. 1999. Role of surface proteins in Vibrio cholerae attachment to chitin. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:1348-1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van de Braak, C. B., M. H. Botterblom, N. Taverne, W. B. van Muiswinkel, J. H. Rombout, and W. P. van der Knaap. 2002. The roles of hemocytes and the lymphoid organ in the clearance of injected Vibrio bacteria in Penaeus monodon shrimp. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 13:293-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vasta, G. R., H. Ahmed, N. E. Fink, M. T. Elola, A. G. Marsh, A. Snowden, and E. W. Odom. 1994. Animal lectins as self/non-self recognition molecules. Biochemical and genetic approaches to understanding their biological roles and evolution. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 712:55-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Watnick, P. I., K. J. Fullner, and R. Kolter. 1999. A role for the mannose-sensitive hemagglutinin in biofilm formation by Vibrio cholerae El Tor. J. Bacteriol. 181:3606-3609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Watnick, P. I., and R. Kolter. 1999. Steps in the development of a Vibrio cholerae El Tor biofilm. Mol. Microbiol. 34:586-595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]