Abstract

The Rap1 small GTPase has been implicated in regulation of integrin-mediated leukocyte adhesion downstream of various chemokines and cytokines in many aspects of inflammatory and immune responses. However, the mechanism for Rap1 regulation in the adhesion signaling remains unclear. RA-GEF-2 is a member of the multiple-member family of guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) for Rap1 and characterized by the possession of a Ras/Rap1-associating domain, interacting with M-Ras-GTP as an effector, in addition to the GEF catalytic domain. Here, we show that RA-GEF-2 is specifically responsible for the activation of Rap1 that mediates tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α)-triggered integrin activation. In BAF3 hematopoietic cells, activated M-Ras potently induced lymphocyte function–associated antigen 1 (LFA-1)-mediated cell aggregation. This activation was totally abrogated by knockdown of RA-GEF-2 or Rap1. TNF-α treatment activated LFA-1 in a manner dependent on M-Ras, RA-GEF-2, and Rap1 and induced activation of M-Ras and Rap1 in the plasma membrane, which was accompanied by recruitment of RA-GEF-2. Finally, we demonstrated that M-Ras and RA-GEF-2 were indeed involved in TNF-α–stimulated and Rap1-mediated LFA-1 activation in splenocytes by using mice deficient in RA-GEF-2. These findings proved a crucial role of the cross-talk between two Ras-family GTPases M-Ras and Rap1, mediated by RA-GEF-2, in adhesion signaling.

INTRODUCTION

The integrin family member lymphocyte function–associated antigen 1 (LFA-1), a heterodimer consisting of αL and β2 subunits, is involved in diverse aspects of leukocyte function, including extravasation, migration, and immunological synapse formation with antigen-presenting cells (Dustin et al., 2004; Kinashi, 2005). Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) interacts with LFA-1 with the highest affinity to mediate adhesion. LFA-1 on circulating lymphocytes has low avidity, which is required to be up-regulated by extracellular stimuli for ligand binding. Intracellular signals that increase LFA-1 avidity, which are called “inside-out” signals, are triggered by various cytokines, chemokines, and antigen stimulation of the T-cell receptor. Although diverse signaling molecules have been implicated in the regulation of LFA-1 avidity, mechanisms underlying this signaling remain largely unknown.

Rap1 is a member of the Ras family of small GTPases and is highly expressed in hematopoietic cells including lymphocytes (Bos et al., 2001; Stork and Dillon, 2005). In its GTP-bound active form, Rap1 interacts with various effector molecules to initiate downstream signaling pathways. The first identified Rap1 function is the antagonism to Ras-dependent activation of the Raf-1/extracellular signal–regulated kinase cascade (Kitayama et al., 1989; Cook et al., 1993), which may also underlie the role of Rap1 in T-cell anergy (Boussiotis et al., 1997). Another Raf family member B-Raf, in contrast to Raf-1, is directly activated by Rap1, leading to the activation of the extracellular signal–regulated kinase pathway (Ohtsuka et al., 1996; Vossler et al., 1997). The different Rap1 action on these two Raf kinases is attributable to the difference in affinity of Rap1 to the cysteine-rich domain (Okada et al., 1999).

The involvement of Rap1 in integrin-mediated cell adhesion was proposed from the effect of the overexpression of activated Rap1 and its negative regulator SPA-1 (Tsukamoto et al., 1999; Caron et al., 2000; Katagiri et al., 2000; Reedquist et al., 2000). Two Rap1 effectors, RAPL and RIAM, have been shown to act as a link between activated Rap1 and integrin (Katagiri et al., 2003; Lafuente et al., 2004). RAPL was isolated as a Rap1 effector enriched in lymphoid tissues, containing a Ras/Rap1-associating (RA) domain and was shown to induce lymphocyte polarization and the redistribution of LFA-1, leading to enhanced adhesion (Katagiri et al., 2003). In support of a pivotal role for RAPL, RAPL gene knockout, in fact, caused an impairment in lymphocyte adhesion and migration (Katagiri et al., 2004). Recently, the serine/threonine kinase Mst1 was identified as a binding protein of RAPL, and its involvement in chemokine-induced cell polarization and LFA-1–mediated adhesion was demonstrated (Katagiri et al., 2006).

The activation of Rap1 in response to various upstream signals is mediated by guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs; Bos et al., 2001). The first identified Rap1 GEF, termed C3G, associates with the adaptor protein Crk and forms a complex with receptor and nonreceptor protein tyrosine kinases in response to extracellular stimuli (Gotoh et al., 1995). Epac1 (also called cAMP-GEFI) and Epac2 (also called cAMP-GEFII) are activated by direct binding of cAMP, being responsible for cAMP-dependent Rap1 activation (de Rooij et al., 1998; Kawasaki et al., 1998a; de Rooij et al., 2000). Another Epac subfamily member called Repac (also called GFR/MR-GEF) binds to the activated form of M-Ras, which down-regulates the activity of Repac (Ichiba et al., 1999; de Rooij et al., 2000; Rebhun et al., 2000). The third subfamily is constituted of two calcium- and diacylglycerol-regulated Rap1 GEFs termed CalDAG-GEFI and CalDAG-GEFIII, which contain calcium-binding EF-hand and diacylglycerol-binding C1 domains (Kawasaki et al., 1998b; Yamashita et al., 2000).

Two related GEFs called RA-GEF-1 (also called PDZ-GEF1/nRapGEP/CNrasGEF; de Rooij et al., 1999; Liao et al., 1999; Ohtsuka et al., 1999; Pham et al., 2000) and RA-GEF-2 (Gao et al., 2001) constitute another Rap1 GEF subfamily. These two GEFs have both GEF and RA domains, serving not only as an upstream regulator, but also as a downstream target, of Ras family small GTPases. In fact, RA-GEF-1 acts both downstream and upstream of Rap1, amplifying Rap1-dependent B-Raf activation in the Golgi apparatus (Liao et al., 1999, 2001). On the other hand, RA-GEF-2 mediates M-Ras–dependent Rap1 activation in the plasma membrane (Gao et al., 2001). Although RA-GEF-1 and RA-GEF-2 have been biochemically characterized as a link between Ras family small GTPases, specific signaling that involves these GEFs and Rap1 remains elusive. Furthermore, the physiological function of these GEFs in developing and adult mice remains totally unknown.

In this article, we examine the role of RA-GEF-2 in the regulation of Rap1 that is responsible for integrin-mediated lymphocyte adhesion by using both cultured cell lines and RA-GEF-2–deficient mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and cDNA Transfection

The mouse hematopoietic cell line BAF3 expressing human LFA-1 (BAF/hLFA-1) was suspended with RPMI 1640 containing 2 mM l-glutamine, 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol, 10% fetal bovine serum, and 10% WEHI-3B–conditioned medium as a source of interleukin (IL)-3 (Katagiri et al., 2000). The cDNA for constitutively active mutant human M-Ras (M-Ras[Q71L]) was subcloned into a mammalian expression vector, pcDNA3.1HisC (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), generating pcDNA3.1HisC-M-Ras[Q71L]. For the stable expression of M-Ras[Q71L], BAF/hLFA-1 cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1HisC-M-Ras[Q71L] by electroporation at 300 V and 900 μF and incubated for 24 h at 37°C. After incubation, cells were selected with G418 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at 1 mg/ml, and several BAF/hLFA-1/M-Ras[Q71L] clones were isolated by a limiting dilution. Construction of pFLAG-CMV2-M-Ras[Q71L], pFLAG-CMV2-M-Ras, pFLAG-CMV2-H-Ras, pFLAG-CMV2-Rap1, and pEF-BOS-HA-Rap1 was previously described (Liao et al., 1999; Gao et al., 2001). These plasmids were introduced into BAF/hLFA-1 cells by electroporation as described above.

Antibodies

Anti-RA-GEF-2 antiserum against a synthetic peptide (CLEPRDTTDPVYKTVTSSTD), which corresponds to the C-terminal amino acid sequence of RA-GEF-2, was raised in rabbits (Operon Biotechnologies, Tokyo, Japan). The antibody was affinity-purified from the antiserum using Sepharose 4B resin conjugated with the antigenic peptide. Mouse monoclonal anti-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), goat polyclonal anti-M-Ras (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rabbit polyclonal anti-Rap1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), mouse monoclonal anti-FLAG (Sigma), mouse monoclonal anti-6×His (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA), and mouse monoclonal anti-hemagglutinin (HA; Invivogen, San Diego, CA), mouse monoclonal anti-human LFA-1 (MEM-25; Monosan, Uden, The Netherlands), and rat monoclonal anti-mouse LFA-1 (M17/4; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibodies were commercially obtained.

Immunoblotting

Proteins were extracted from BAF3-derived cells or mouse tissues by lysis buffer A (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 200 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 1% Nonidet P-40, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM leupeptin) and subjected to SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Whatman, Brentford, United Kingdom) and incubated with primary antibodies, followed by horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies. The enhanced chemiluminescence system (GE Healthcare BioSciences, Piscataway, NJ) was applied for detection.

Gene Silencing by RNA Interference

BAF3-derived cells were transfected with Stealth small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) against mouse RA-GEF-2 (sense sequence; 5′-ggacuccugaggacuuaaauauuau-3′), mouse Rap1A (sense sequence; 5′-aaggacuacuagcuuguacucacgc-3′), and control (negative control Med GC) by electroporation at 300 V and 300 μF. After electroporation, cells were incubated for 48 h at 37°C and subjected to further experiments. Spleen cells were transfected with siRNAs against mouse M-Ras (sense sequence; 5′-ucagguaggagucuucaaugguggg-3′) and control followed by incubation for 24 h at 37°C. Stealth siRNAs were purchased from Invitrogen.

Immunostaining

BAF/hLFA-1 cells were transfected with pFLAG-CMV2-M-Ras[Q71L], incubated for 24–32 h at 37°C, and then serum-starved for another 16 h. After fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, cells were mounted on aminosilane-coated slide glasses (Matsunami Glass, Osaka, Japan) until dried up and were permeabilized by cold methanol for 1 min on ice. Cells were stained with mouse monoclonal anti-FLAG antibody and Alexa Fluor 546–labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for M-Ras[Q71L], and anti-RA-GEF-2 antibody and Alexa Fluor 488–labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L; Molecular Probes) for endogenous RA-GEF-2. After staining, cells were observed by confocal laser scanning microscopy (LSM510 META; Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany).

Cell Preparation from the Thymus and Spleen

Thymocytes and splenocytes were prepared essentially as described (Kawasaki et al., 2006; Sebzda et al., 2002; Duchniewicz et al., 2006). The thymus and spleen were disaggregated with fine forceps, passed through a fine mesh filter to obtain a single-cell suspension, and washed twice with Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS; Invitrogen). After washing, cells were incubated for 5 min in erythrocyte lysis buffer (155 mM NH4Cl, 10 mM KHCO3, 0.1 mM EDTA) to remove erythrocytes and washed with HBSS three times.

Adhesion Assays

BAF/hLFA-1 cells were transfected with pFLAG-CMV2-M-Ras, pFLAG-CMV2-H-Ras, pFLAG-CMV2-Rap1, or a combination of pFLAG-CMV2-M-Ras and pEF-BOS-HA-Rap1 and incubated for 48 h at 37°C. Maxisorb 96-well plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) were coated with 100 μl of 2 μg/ml ICAM-1/Fc (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Invitrogen) at 4°C overnight, washed three times with PBS, and blocked with 2% bovine serum albumin in HBSS for 1 h at 37°C. The blocked 96-well plates were washed three times with 0.5% bovine serum albumin in HBSS. Cells were collected and washed with HBSS three times and stained with 2.5 μM biscarboxyethyl-carboxyfluorescein acetoxymethylether (BCECF/AM; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) in HBSS for 30 min at 37°C. After staining, cells were washed with HBSS three times and suspended in adhesion assay medium (RPMI 1640 containing 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, and 5% fetal bovine serum). Stained BAF3-derived cells (1 × 105/well) or thymus and spleen cells (1 × 106/well) suspended in 100 μl of adhesion assay medium were stimulated with phorbol myristate acetate (PMA; 10 ng/ml) or tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α; 10 ng/ml) for 30 min at 37°C. For inhibition, stained cells were incubated with 20 μg/ml anti-human LFA-1 (MEM-25) or anti-mouse LFA-1 (M17/4) antibodies for 30 min before loading (Garnotel et al., 1995; Mueller et al., 2004). Nonadherent cells were removed by washing three times with adhesion assay medium prewarmed at 37°C. Cells bound to ICAM-1 were detected by fluorescence analyzer (FLA3000G; Fuji-film, Tokyo, Japan) at an excitation of 473 nm and an emission of 520 nm. The adhesion was represented as a percentage of total input detected before incubation.

Production of Recombinant Retrovirus and Infection

The SPA-1 cDNA was a generous gift from Drs. Masakazu Hattori and Nagahiro Minato (Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan). Retroviral expression vectors pLPCX (Clontech) and pLPCX carrying the FLAG-tagged mouse SPA-1 cDNA were introduced into Phoenix ecotropic retroviral packaging cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA; inventory no. SD3444) with the Superfect transfection reagent (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol to produce the viral supernatant. After incubation for 48 h at 37°C, the viral supernatant was collected, filtrated, and used for infection. BAF/hLFA-1/M-Ras[Q71L] cells (5 × 105) were suspended in 1 ml of the viral supernatant with 10 μg/ml polybrene for 2 h at 32°C. After infection, cells were incubated in medium for 24 h at 37°C and then selected for 10 d in the presence of 2 μg/ml puromycin.

Preparation of the Plasma Membrane Fraction

pEF-BOS-HA-Rap1 was transfected into BAF/hLFA-1 cells with or without pFLAG-CMV2-M-Ras[Q71L]. After transfection, cells were incubated for 24–32 h at 37°C and then serum-starved for another 16 h. To see TNF-α–dependent activation of M-Ras and Rap1, pFLAG-CMV2-M-Ras and pEF-BOS-HA-Rap1 were cotransfected into BAF/hLFA-1 cells and incubated for 48 h at 37°C. After incubation, cells were treated with or without 10 ng/ml TNF-α for 30 min at 37°C. The plasma membrane fraction was prepared by sucrose density gradient centrifugation as described (Gao et al., 2001). In this fraction, the plasma membrane is highly enriched as estimated by the specific activity of the marker enzyme alkaline phosphatase (Gao et al., 2001). The plasma membrane fraction resuspended in lysis buffer A was subjected to pulldown assays. For in vivo study, the plasma membrane–enriched fraction was prepared from spleen cells of wild-type mice as described (Peirce et al., 2004) with minor modifications. Briefly, spleen cells were transfected with siRNAs against mouse M-Ras and control for 24 h at 37°C, followed by TNF-α treatment for 30 min at 37°C. After treatment, cells were resuspended in hypotonic lysis buffer B (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride), homogenized using a Potter-Elvehjem homogenizer and centrifuged at 4000 × g for 5 min. The supernatant was further centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 30 min, and the pellet containing the plasma membrane, but not microsomes, was resuspended in lysis buffer A and subjected to pulldown assays.

Pulldown Assays

Extracts from the plasma membrane fraction or plasma membrane-enriched fraction prepared by lysis buffer A were added to the RalGDS-Ras–interacting domain (RID; for Rap1-GTP) or the c-Raf-Ras-binding domain (for M-Ras-GTP), which had been immobilized on glutathione agarose resins, and mixed with slow agitation for 1 h at 4°C. Resins were washed three times with lysis buffer A, and bound proteins were eluted from resins by SDS-PAGE sample buffer followed by immunoblotting.

Flow Cytometric Analysis

Spleen cells were incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated anti-mouse LFA-1 (M17/4) antibody (1 μg per 1 × 106 cells) in HBSS on ice for 30 min, washed with HBSS three times, and subjected to flow cytometric analysis by FACScaliber (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA).

Separation of Splenic B- and non-B-Cells

Polystyrene flasks (25 cm2, Corning Glass Works, Corning, NY) were coated with 2 ml of 1 mg/ml rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulins antibody (DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) in PBS at 4°C overnight and washed three times with PBS. After preparation of splenocytes, cells were resuspended in adhesion assay medium (1.5 × 107/ml), and 3 ml of cell suspension was added to the flask. After incubation for 1 h at 37°C with gentle swirling, nonadherent cells (non-B-cell enrichment, 4.5 × 107 cells/spleen) were carefully resuspended by rocking the flask and were recovered from the cell suspension medium. The flask with adherent cells (B-cell enrichment, 1.0 × 108 cells/spleen) was washed five times with PBS, and 2 ml of 4 mg/ml lidocaine (Sigma) solution in PBS was added. After incubation for 15 min, cells were removed from the flask by pipetting, collected by centrifugation (200 × g, 10 min), and washed twice with PBS.

Construction of the Targeting Vector

An RA-GEF-2 genomic DNA fragment was cloned from a 129/Sv mouse genomic bacterial artificial chromosome library (Invitrogen) and used for the construction of a targeting vector. A 522-base pair MfeI-BsgI fragment, which harbors exon 21 of RA-GEF-2 coding for the part of the GEF domain, was inserted into a construct in which it is flanked with loxP at its 5′end and with loxP-TK-neo-loxP at its 3′ end. TK-neo, which expresses the neomycin-resistance gene under the control of the thymidine kinase promoter, was inserted in an inverted orientation. Subsequently, a 9.2-kb KpnI-MfeI fragment and a 4.3-kb BsgI-StyI fragment of RA-GEF-2 were inserted as the 5′- and 3′-arms for homologous recombination, respectively (see Figure 5A). Finally, the diphtheria toxin A chain cassette for negative selection was inserted into the 3′end of the right arm.

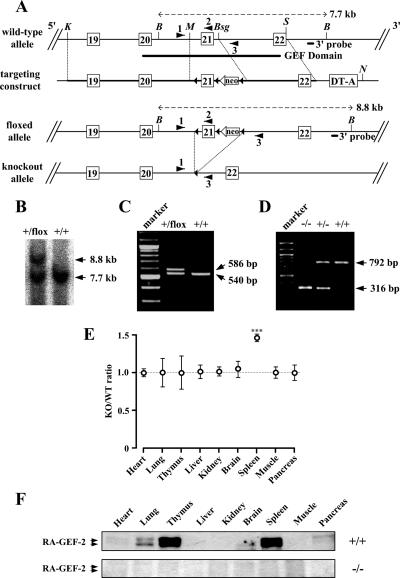

Figure 5.

Targeted disruption of the mouse RA-GEF-2 gene. (A) Schematic representation of the wild-type allele (RA-GEF-2+), the floxed allele (RA-GEF-2flox), and the knockout allele (RA-GEF-2−). Exons 19–22 (white rectangles), loxP sites (black triangles), TK-neo (neo), and diphtheria toxin A chain cassette (DT-A) are indicated in the targeting construct. The 3′ probe for Southern blot analysis, a trio of primers for genotyping by PCR, and restriction enzyme sites (K, KpnI; B, Bsu36I; M, MfeI; Bsg, BsgI; S, StyI; N, NotI) are also shown. (B) Southern blot analysis of the RA-GEF-2 gene. Genomic DNA was prepared from mouse tails, digested by Bsu36I, and hybridized with the 3′ external probe. The RA-GEF-2+ allele generated a 7.7-kb band, and the RA-GEF-2flox allele generated an 8.8-kb band. (C) PCR analysis of the leftmost loxP. Genomic DNA was prepared from mouse tails and analyzed by PCR. Primers 1 and 2 generated a 540-base pair band from RA-GEF-2+ allele and a 586-base pair band from the RA-GEF-2flox allele. (D) PCR-based genotyping of RA-GEF-2 knockout. Primers 1 and 3 generated a 792-base pair band from the RA-GEF-2+ allele and a 316-base pair band from the RA-GEF-2− allele. (E) Comparison of tissue-to-body weight ratios between RA-GEF-2−/− (KO) and wild-type (WT) mice. At least seven mice of each genotype were examined at the ages of 8 wk. ***p < 0.001. (F) Immunoblot analysis for RA-GEF-2. Protein extracts were prepared from tissues and used for immunoblotting by anti-RA-GEF-2 antibody.

Gene Targeting and Generation of Mutant Mice

To generate the floxed RA-GEF-2 (RA-GEF-2flox) allele, in which exon 21 is flanked with loxP sites (see Figure 5A), mouse EB3 embryonic stem (ES) cells (a gift from Dr. Hitoshi Niwa, RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology, Kobe, Japan) derived from the 129/Ola strain were transfected with the targeting vector, linearized by NotI cleavage, by electroporation at 0.8 kV and 3 μF, and subjected to selection with G418. G418-resistant 768 clones were isolated and screened by Southern blot analysis of their genomic DNAs. One ES clone, carrying the properly generated RA-GEF-2flox allele, was injected into mouse C57BL/6 blastocysts to generate chimeric males, which were subsequently bred with C57BL/6 females to generate RA-GEF-2+/flox mice. Subsequently, RA-GEF-2+/flox mice were bred with CAG-Cre transgenic mice (a generous gift from Dr. Jun-ichi Miyazaki, Osaka University, Osaka, Japan; Sakai and Miyazaki, 1997) to yield RA-GEF-2+/− mice carrying an RA-GEF-2 allele with a deletion of exon 21-loxP-TK-neo by Cre-mediated recombination between the terminal loxP sites. Finally, RA-GEF-2−/− mice were generated by interbreeding RA-GEF-2+/− mice. All animals were maintained under standard housing condition with a 12-h–12-h dark-light cycle at the animal facilities of Kobe University Graduate School of Medicine according to institutional guidelines.

Genotyping by Southern Blotting and PCR

Genomic DNAs isolated from ES cells or mouse tails were digested by Bsu36I, separated by agarose gel electrophoresis and transferred to a nylon membrane (Hybond N+, GE Healthcare BioSciences) with alkaline transfer buffer (0.4 N NaOH, 0.6 M NaCl). Membranes were hybridized with the 32P-radiolabeled 3′ probe (see Figure 5A) generated by PCR (the sense and antisense primers were 5′-ccgtcatattattcgaatgacttctgcc-3′ and 5′-gcctcagctataaagtgagtacag-3′, respectively), and the hybridized signals were detected by STORM bioimage analyzer (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences). For genotyping by PCR, a trio of primers were used for amplification of the RA-GEF-2 alleles: 1 (5′-gagccttgagatacagaaacttg-3′) located upstream of the 5′-terminal loxP site in the RA-GEF-2flox allele; 2 (5′-cttgacaacagggaagagtg-3′) in exon 21; and 3 (5′-ctagggaggtgtcagcaaag-3′) downstream of the 3′-terminal loxP site. The amplified DNA fragments were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis.

RT-PCR Analysis

Mouse spleen cells were transfected with siRNAs against mouse M-Ras and control, incubated for 24 h at 37°C, and treated with TNF-α for 30 min at 37°C. Transcripts were prepared by using the Sepasol(R)-RNA I Super kit (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The first-strand oligo(dT)-primed cDNA was synthesized as previously described (Wu et al., 2003). Primers used for amplification of M-Ras were 5′-cgctgttccaagtgaaaacc-3′ and 5′-ggctgtcacaagatgacac-3′. Primers used for amplification of RA-GEF-2 were 5′-gaggcacttgggaaaagttg-3′ and 5′-cttgacaacagggaagagtg-3′. Primers for amplification of mouse glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; 5′-gtgaaggtcggtgtgaacggattt-3′, and 5′-cacagtcttctgagtggcagtgat-3′) were used as an internal control.

RESULTS

RA-GEF-2 Mediates M-Ras–induced Rap1 Activation and LFA-1-ICAM-1–dependent Cell Aggregation

To evaluate the involvement of M-Ras and RA-GEF-2 in cell adhesion through the interaction between LFA-1 and ICAM-1, we used the BAF/hLFA-1 cell line, which was derived from nonadherent IL-3–dependent mouse BAF3 cells (Katagiri et al., 2000). BAF/hLFA-1 cells stably express human LFA-1 and show PMA-dependent adhesion to ICAM-1 (Katagiri et al., 2000). In addition, overexpression of constitutively activated Rap1 potently enhanced the binding of BAF/hLFA-1 cells to ICAM-1, suggesting that Rap1 is involved in LFA-1-ICAM-1–dependent cell adhesion (Katagiri et al., 2000). We isolated a BAF/hLFA-1–derived clone (designated BAF/hLFA-1/M-Ras[Q71L]), which stably expresses constitutively activated M-Ras mutant (M-Ras[Q71L]; Figure 1A). Endogenous RA-GEF-2 may exist as two splice variants, as suggested by doublet bands in immunoblot analysis (Figure 1A), and the occurrence of two mRNA species was previously reported (Gao et al., 2001). The expression of endogenous M-Ras in BAF/hLFA-1 cells was undetectable by anti-M-Ras antibody (Figure 1A). BAF/hLFA-1/M-Ras[Q71L] cells have an increased tendency to aggregate, which was completely suppressed in the presence of anti-human LFA-1 antibody, indicating that M-Ras–dependent cell aggregation was indeed mediated by LFA-1-ICAM-1 interaction (Figure 1B). We hypothesized that RA-GEF-2 may activate endogenous Rap1 upon overexpression of activated M-Ras, leading to the formation of cell aggregates. In fact, when the expression of RA-GEF-2 was abrogated by RNA interference (RNAi), LFA-1–dependent cell aggregation and adhesion to ICAM-1 were significantly reduced (Figure 2, A–C). Similarly, the decrease in the expression level of Rap1 by its specific siRNA inhibited the M-Ras[Q71L]–dependent cell aggregation and adhesion to ICAM-1, thus placing Rap1 downstream of M-Ras (Figure 2, A–C). Reduction in adhesion to ICAM-1 by RA-GEF-2 or Rap1 knockdown was almost complete because adhesion of parental BAF/hLFA-1 cells to ICAM-1 was 8.4 ± 2.2%. Furthermore, overexpression of SPA-1, a GTPase-activating protein specific for Rap1, which negatively regulates Rap1 activity, potently inhibited M-Ras–induced cell aggregation (Figure 2, D and E). Rap2, another substrate for RA-GEF-2, was not expressed in BAF/hLFA-1 cells, as determined by RT-PCR (data not shown).

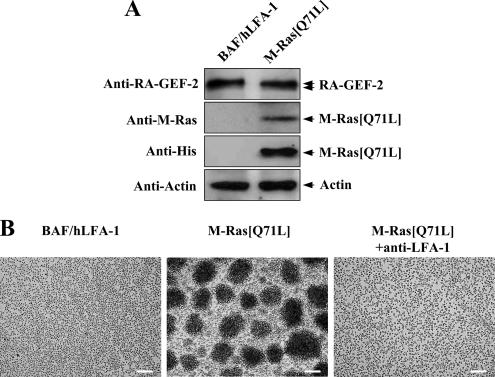

Figure 1.

Induction of LFA-1–mediated cellular aggregation by M-Ras[Q71L]. (A) Expression of endogenous RA-GEF-2, but not M-Ras. Protein extracts from BAF/hLFA-1 and BAF/hLFA-1/M-Ras[Q71L] cells were used for immunoblotting to detect endogenous RA-GEF-2 by anti-RA-GEF-2 antibody. Anti-M-Ras and anti-6×His antibodies were used to detect total M-Ras and M-Ras[Q71L], respectively. Anti-actin antibody was used to detect actin as an internal control. (B) M-Ras[Q71L]-induced cellular aggregation. BAF/hLFA-1 cells transfected with or without M-Ras[Q71L] were observed by microscopy. Anti-human LFA-1 antibody (MEM-25) was added to the culture medium to examine the involvement of LFA-1 in the cellular aggregation. The result is representative of more than 10 independent clones, which gave equivalent results. Each bar, 100 μm.

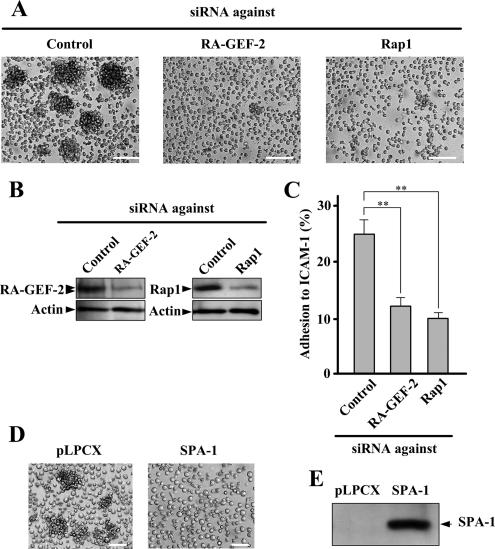

Figure 2.

The involvement of RA-GEF-2 and Rap1 in M-Ras[Q71L]–induced cellular aggregation. (A) Inhibition of M-Ras[Q71L]–induced cellular aggregation by down-regulation of RA-GEF-2 and Rap1. BAF/hLFA-1/M-Ras[Q71L] cells transfected with siRNAs against control (Control), RA-GEF-2, and Rap1 were observed by microscopy. Each bar, 100 μm. (B) siRNA-induced reduction of protein expression. After siRNA treatment, protein extracts were prepared and used for immunoblotting by anti-RA-GEF-2 and Rap1 antibodies. (C) Inhibition of M-Ras[Q71L]–induced adhesion to ICAM-1 by down-regulation of RA-GEF-2 and Rap1. BAF/hLFA-1/M-Ras[Q71L] cells transfected with siRNAs against control (Control), RA-GEF-2, and Rap1 were examined for adhesion to ICAM-1. Cells bound to ICAM-1 were detected by fluorescence analyzer. Bars represent the average and SE of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. **p < 0.01. (D) Inhibition of M-Ras[Q71L]–induced cellular aggregation by SPA-1. SPA-1 was not expressed (pLPCX) or expressed (SPA-1) in BAF/hLFA-1/M-Ras[Q71L] cells, and cells were observed by microscopy. Each bar, 50 μm. (E) The expression of SPA-1. Protein extracts prepared from cells shown in D were used to confirm the expression of SPA-1 by immunoblotting using anti-FLAG antibody.

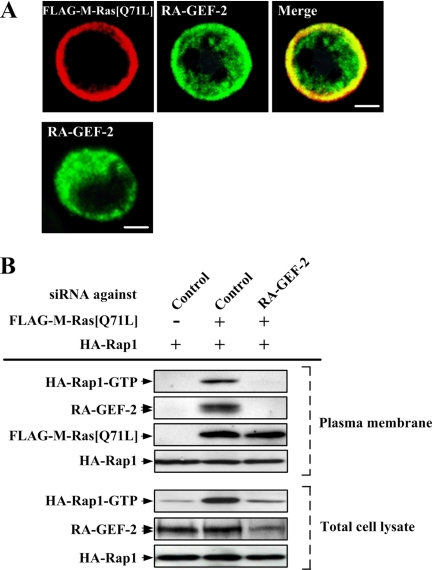

We have shown that in COS-7 cells activated M-Ras was expressed exclusively in the plasma membrane, and RA-GEF-2 was recruited from the cytoplasm to the plasma membrane through the binding of its RA domain to M-Ras, when they were coexpressed (Gao et al., 2001). Likewise, activated M-Ras and RA-GEF-2 seemed to be colocalized, in part, in the plasma membrane in BAF/hLFA-1/M-Ras[Q71L] cells, whereas RA-GEF-2 was localized throughout the cytoplasm when expressed alone in BAF/hLFA-1 cells (Figure 3A). In the majority of cells investigated, these proteins showed equivalent subcellular localization. Recruitment of RA-GEF-2 to the plasma membrane was also detected by immunoblot analysis when constitutively activated M-Ras was expressed (Figure 3B). The GTP-bound active form of plasma membrane–localized Rap1 was consequently increased as shown by pulldown assay in activated M-Ras–expressing cells (Figure 3B). In addition, down-regulation of RA-GEF-2 by RNAi inhibited Rap1 activation in the plasma membrane, indicating that RA-GEF-2 mediated M-Ras–induced Rap1 activation (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

RA-GEF-2 recruitment and Rap1 activation in the plasma membrane by M-Ras[Q71L]. (A) Colocalization of M-Ras[Q71L] and RA-GEF-2 in the plasma membrane. FLAG-M-Ras[Q71L] and endogenous RA-GEF-2 in FLAG-M-Ras[Q71L]–transfected (top panels) or mock-transfected (bottom panel) BAF/hLFA-1 cells were detected by anti-FLAG and anti-RA-GEF-2 antibodies, respectively. Each bar, 5 μm. (B) Rap1 activation and RA-GEF-2 recruitment in the plasma membrane fraction by M-Ras[Q71L]. HA-Rap1 was expressed with or without FLAG-M-Ras[Q71L] in BAF/hLFA-1 cells. Cells were treated with siRNAs against control (Control) and RA-GEF-2, and extracts of the plasma membrane fraction were prepared after serum starvation. The GTP-bound form of HA-Rap1 in the plasma membrane fraction, and the total cell lysate was precipitated by the use of GST-RalGDS-RID and detected by immunoblotting using anti-HA antibody. The expression of endogenous RA-GEF-2, FLAG-M-Ras[Q71L] and HA-Rap1 in the plasma membrane fraction was monitored by immunoblotting using anti-RA-GEF-2, anti-FLAG, and anti-HA antibodies, respectively. The expression of endogenous RA-GEF-2 and HA-Rap1 in total cell lysates was also monitored by anti-RA-GEF-2 and anti-HA antibodies, respectively.

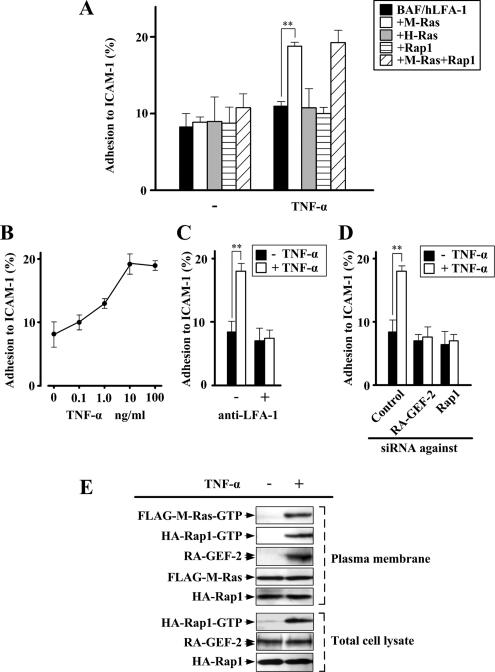

TNF-α Induces LFA-1-ICAM-1–dependent Adhesion Specifically through M-Ras

A diverse array of cytokines modulates LFA-1-ICAM-1–dependent lymphocyte adhesion. As a step to identify cytokines that stimulate the M-Ras-RA-GEF-2-Rap1 pathway to induce cell adhesion, we examined the involvement of M-Ras in integrin activation signaling downstream of the TNF-α receptor because Rap1 was reported to mediate TNF-α–triggered activation of integrins (Caron et al., 2000). For this purpose, we isolated BAF/hLFA-1–derived clones that express wild-type M-Ras, Ha-Ras, or Rap1 and then compared adhesion to ICAM-1 upon TNF-α treatment. TNF-α selectively induced the adhesion of BAF/hLFA-1 cells harboring M-Ras, but not those harboring Ha-Ras or Rap1 (Figure 4A). PMA, as a positive control, enhanced the adhesion of all of the above cell lines (data not shown). Coexpression of Rap1 did not enhance M-Ras–mediated cell adhesion in response to TNF-α, suggesting that the expression level of endogenous Rap1 is sufficiently high in BAF/hLFA-1 cells (Figure 4A). The effect of TNF-α in M-Ras–expressing cells was dose-dependent, with maximal induction at the concentration of 10–100 ng/ml (Figure 4B). TNF-α–induced adhesion of these cells was indeed blocked by anti-LFA-1 antibody (Figure 4C). In addition, down-regulation of RA-GEF-2 or Rap1 expression by respective siRNAs rendered cells insensitive to TNF-α (Figure 4D). TNF-α also induced the recruitment of RA-GEF-2 to the plasma membrane in cells expressing wild-type M-Ras (Figure 4E). This recruitment occurred presumably through the specific interaction of RA-GEF-2 with the GTP-bound form of M-Ras in the plasma membrane generated upon stimulation with TNF-α (Figure 4E). The Rap1-GTP level in the plasma membrane was also increased after TNF-α stimulation, probably due to the action of RA-GEF-2 recruited to this region (Figure 4E). Amounts of plasma membrane-localized M-Ras and Rap1 were unaffected by TNF-α treatment (Figure 4E). Taken together, in BAF3-derived cells, TNF-α specifically activated the signaling pathway consisting of M-Ras, RA-GEF-2 and Rap1, leading to LFA-1–dependent cell adhesion.

Figure 4.

Induction of LFA-1–mediated adhesion to ICAM-1 via M-Ras by TNF-α. (A) Induction of adhesion to ICAM-1 in M-Ras–expressing BAF/hLFA-1 cells by TNF-α. BAF/hLFA-1 cells transfected with M-Ras, H-Ras, Rap1, or a combination of M-Ras and Rap1 were examined for adhesion to ICAM-1 in the presence and absence of TNF-α. Cells bound to ICAM-1 were detected by fluorescence analyzer. Each bar represents the average and SE of six independent experiments performed in triplicate. **p < 0.01. (B) Dose dependency of TNF-α on adhesion to ICAM-1. M-Ras–expressing BAF/hLFA-1 cells were treated with TNF-α (0.1–100 ng/ml) and examined for adhesion to ICAM-1. (C) Inhibition of TNF-α–induced adhesion to ICAM-1 by anti-human LFA-1 (MEM-25) antibody. After treatment with anti-LFA-1 antibody, M-Ras–expressing BAF/hLFA-1 cells were treated with or without TNF-α and examined for adhesion to ICAM-1. **p < 0.01. (D) Inhibition of adhesion to ICAM-1 by down-regulation of RA-GEF-2 and Rap1. M-Ras–expressing BAF/hLFA-1 cells transfected with siRNAs against control (Control), RA-GEF-2, or Rap1 were treated with or without TNF-α and examined for adhesion to ICAM-1. Data in B–D are shown as the average and SE of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. **p < 0.01. (E) The activation of M-Ras and Rap1 and RA-GEF-2 recruitment in the plasma membrane fraction in response to TNF-α. FLAG-M-Ras and HA-Rap1 were coexpressed in BAF/hLFA-1 cells, and extracts of the plasma membrane fraction were prepared after TNF-α treatment. The GTP-bound form of FLAG-M-Ras was precipitated from the extracts by the use of GST-c-Raf-Ras–binding domain and detected by immunoblotting using anti-FLAG antibody. The GTP-bound form of HA-Rap1 in the plasma membrane fraction and the total cell lysate was precipitated by the use of GST-RalGDS-RID and detected by immunoblotting using anti-HA antibody. The amount of endogenous RA-GEF-2, FLAG-M-Ras, and HA-Rap1 in the plasma membrane fraction was monitored by immunoblotting using anti-RA-GEF-2, anti-FLAG and anti-HA antibodies, respectively. The amount of endogenous RA-GEF-2 and HA-Rap1 in total cell lysates was also monitored by anti-RA-GEF-2 and anti-HA antibodies, respectively.

Generation of RA-GEF-2–deficient Mice

To evaluate the physiological relevance of the M-Ras-RA-GEF-2-Rap1 pathway in terms of lymphocyte adhesion, we generated mice with functional disruption of the RA-GEF-2 gene. We first created mice carrying an RA-GEF-2 allele with exon 21 (encoding the GEF domain) and the TK-neo cassette flanked by loxP sites (floxed allele; Figure 5A). Hybridization of Bsu36I-digested genomic DNAs with a 3′ external probe identified 7.7- and 8.8-kb bands of the wild-type and floxed alleles, respectively, in RA-GEF-2+/flox mice (Figure 5B). Insertion of the 5′ loxP site was also confirmed by PCR. Primers 1 and 2 (described in Figure 5A) amplified 540- and 586-base pair products from the wild-type and floxed alleles, respectively (Figure 5C). RA-GEF-2+/flox mice were then bred with mice carrying a transgene encoding the Cre recombinase under the control of the CAG promoter (Sakai et al., 1997). Out-of-frame deletion of exon 21 resulted in functional disruption of the RA-GEF-2 allele (knockout allele). RA-GEF-2+/− mice were then intercrossed to produce RA-GEF-2 homozygous null (RA-GEF-2−/−) offspring, in which the RA-GEF-2 knockout allele was confirmed by PCR. Primers 1 and 3 (described in Figure 5A) amplified a 792- and 316-base pair products from the wild-type and knockout alleles, respectively (Figure 5D). RA-GEF-2−/− pups were born at the expected Mendelian ratios (RA-GEF-2+/+:RA-GEF-2+/−:RA-GEF-2−/− = 26.7:47.8:25.6%; 90 pups) without any intrauterine loss or early death and were fertile and indistinguishable from their RA-GEF-2+/+ or RA-GEF-2+/− littermates in appearance and growth. RA-GEF-2−/− mice grew normally for at least 37 wk. Anatomical examination revealed that their spleens were enlarged compared with those of wild-type mice, whereas the other tissues appeared grossly normal (Figure 5E). We observed no obvious histological abnormalities in the RA-GEF-2 knockout spleen.

The expression of the RA-GEF-2 protein in mouse tissues was examined by immunoblotting. RA-GEF-2 was highly expressed in the thymus and spleen and weakly in the lung, brain, and pancreas in a wild-type mouse (Figure 5F). RA-GEF-2 was also weakly expressed in other hematopoietic tissues such as lymph nodes and bone marrow (data not shown). As expected, no RA-GEF-2 protein was detected in RA-GEF-2−/− mouse tissues (Figure 5F).

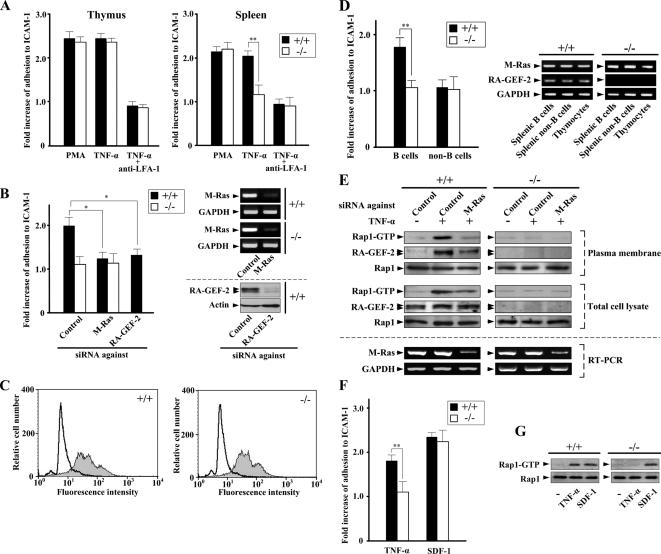

LFA-1-ICAM-1–mediated Adhesion of Mouse Splenocytes

Thymocytes and splenocytes were isolated from wild-type and RA-GEF-2−/− mice, and their adhesion to ICAM-1 was examined. PMA and TNF-α enhanced adhesion of thymocytes and splenocytes from the wild-type mouse (Figure 6A). This adhesion was mediated by LFA-1, as indicated by the inhibitory effect of anti-LFA-1 antibody (Figure 6A). RA-GEF-2 knockout exerted virtually no effect on PMA- or TNF-α–stimulated thymocyte adhesion. In marked contrast, TNF-α–stimulated adhesion of RA-GEF-2−/− splenocytes was significantly reduced compared with wild-type ones, whereas PMA-stimulated adhesion remained unaffected (Figure 6A). Furthermore, down-regulation of the expression of endogenous M-Ras or RA-GEF-2 in splenocytes by RNAi completely blocked TNF-α–stimulated adhesion (Figure 6B). The expression level of LFA-1 on the cell surface of splenocytes did not show any detectable difference between wild-type and RA-GEF-2−/− mice, as determined by FACScan analysis, indicating that the impaired TNF-α–induced adhesion in RA-GEF-2−/− splenocytes was not due to the loss of LFA-1 expression (Figure 6C). To identify the cell population that actually responds to TNF-α, we separated B- and non-B-cells from wild-type and RA-GEF-2−/− spleens, and their adhesion to ICAM-1 was examined. TNF-α–stimulated the adhesion of splenic B-cells, but not non-B-cells, isolated from wild-type mice (Figure 6D). In contrast, B-cells from RA-GEF-2−/− splenocytes did not show any TNF- α–induced adhesion (Figure 6D). The expression level of M-Ras was almost the same in splenic B-cells, splenic non-B-cells, and thymocytes isolated from wild-type and RA-GEF-2−/− knockout mice (Figure 6D). RA-GEF-2 expression levels in these cell types were also similar in wild-type mice (Figure 6D). In addition, we observed similar nuclear translocation of nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) after TNF-α stimulation for 30 min in wild-type and RA-GEF-2–deficient splenic B-cells, suggesting that TNF-α receptor expression did not alter significantly in RA-GEF-2–deficient cells (data not known). Collectively, RA-GEF-2 is indispensable for transduction of TNF-α–induced adhesion signals in splenic B-cells, whereas RA-GEF-2 does not appear to play an essential role in adhesion signaling in thymocytes, even though it is abundantly expressed in the thymus as well.

Figure 6.

Impaired LFA-1–mediated adhesion to ICAM-1 in RA-GEF-2−/− cells from the spleen, but not the thymus. (A) Comparison of adhesion to ICAM-1 between cells from wild-type and RA-GEF-2−/− mice. Thymocytes and splenocytes isolated from wild-type and RA-GEF-2−/− mice were left untreated or treated with PMA and TNF-α. After treatment, cells were examined for adhesion to ICAM-1. Anti-mouse LFA-1 antibody was added 30 min before TNF-α treatment. Fold increase of adhesion to ICAM-1 of cells treated with PMA or TNF-α compared with that of untreated cells was shown. The percentages of adhesion to ICAM-1 of untreated cells are as follows: wild-type thymocytes, 7.6%; RA-GEF-2−/− thymocytes, 7.3%; wild-type splenocytes, 9.7%; and RA-GEF-2−/− splenocytes, 5.9%. Each bar represents the average and SE of six independent experiments performed in triplicate. ■, wild-type mice; □, RA-GEF-2−/− mice; **p < 0.01. (B) Inhibition of TNF-α–induced adhesion to ICAM-1 by down-regulation of M-Ras and RA-GEF-2 in splenocytes. Splenocytes isolated from wild-type and RA-GEF-2−/− mice were transfected with siRNAs against control (Control), M-Ras, and RA-GEF-2 and left untreated or treated with TNF-α. After treatment, cells were examined for adhesion to ICAM-1. Fold increase of adhesion to ICAM-1 of cells treated with TNF-α compared with that of untreated cells is shown. The percentages of adhesion to ICAM-1 of untreated cells are follows: wild-type splenocytes, 9.2%; RA-GEF-2−/− splenocytes, 6.3%. Each bar represents the average and SE of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. ■, wild-type mice; □, RA-GEF-2−/− mice; *p < 0.05. Reduction of the expression of M-Ras and RA-GEF-2 in wild-type (+/+) and RA-GEF-2−/− (−/−) splenocytes by specific siRNAs was confirmed by RT-PCR and immunoblotting, respectively. (C) Equal expression of LFA-1 in wild-type and RA-GEF-2−/− mice. LFA-1 on the cell surface was stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-mouse LFA-1 (M17/4) antibody and analyzed by FACScaliber. White- and gray-colored histograms represent the isotype control, and cells stained with anti-LFA-1 antibody, respectively. (D) TNF-α–induced adhesion of splenic B- and non-B-cells. Splenic B- and non-B-cells isolated from wild-type and RA-GEF-2−/− mice were left untreated or treated with TNF-α. After treatment, cells were examined for adhesion to ICAM-1. Fold increase of adhesion to ICAM-1 of TNF-α–treated cells compared with that of untreated cells was shown. The percentages of adhesion to ICAM-1 of untreated cells are as follows: wild-type B-cells, 5.8%; RA-GEF-2−/− B-cells, 4.6%; wild-type non-B-cells, 11.7%; RA-GEF-2−/− non-B-cells, 11.3%. Each bar represents the average and SE of four independent experiments performed in triplicate. ■, wild-type mice; □, RA-GEF-2−/− mice; **p < 0.01. The expression level of M-Ras and RA-GEF-2 in splenic B-cells, splenic non-B-cells, and thymocytes from wild-type (+/+) and RA-GEF-2−/− (−/−) mice was confirmed by RT-PCR. (E) The activation of Rap1 and RA-GEF-2 recruitment in the plasma membrane fraction in response to TNF-α. Splenocytes isolated from wild-type and RA-GEF-2−/− mice were transfected with siRNAs against control (Control) and M-Ras, and extracts from the plasma membrane–enriched fraction were prepared after TNF-α treatment. The GTP-bound form of endogenous Rap1 in the plasma membrane fraction and the total cell lysate was precipitated from the extracts by the use of GST-RalGDS-RID and detected by immunoblotting using anti-Rap1 antibody. The amount of endogenous RA-GEF-2 and Rap1 in the plasma membrane–enriched fraction was monitored by immunoblotting using anti-RA-GEF-2 and anti-Rap1 antibodies, respectively. The amount of endogenous RA-GEF-2 and Rap1 in total cell lysates was also monitored by anti-RA-GEF-2 and anti-Rap1 antibodies, respectively. Inhibition of M-Ras expression by the siRNA in total cell lysates was confirmed by RT-PCR using primers specific for M-Ras. (F) Adhesion to ICAM-1 of splenocytes in response to TNF-α and SDF-1. Splenocytes isolated from wild-type and RA-GEF-2−/− mice were treated with TNF-α (10 ng/ml) and SDF-1 (100 ng/ml) for 30 and 5 min, respectively, and examined for adhesion to ICAM-1. Fold increase of adhesion to ICAM-1 of cells treated with TNF-α or SDF-1 compared with that of untreated cells was shown. The percentages of adhesion to ICAM-1 of untreated cells are as follows: wild-type splenocytes, 7.7%; RA-GEF-2−/− splenocytes, 5.3%. Each bar represents the average and SE of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. ■, wild-type mice; □, RA-GEF-2−/− mice; ** p < 0.01. (G) The activation of Rap1 in splenocytes treated with TNF-α and SDF-1. Splenocytes isolated from wild-type and RA-GEF-2−/− mice were treated with TNF-α and SDF-1 as in F. After treatment, the GTP-bound form of endogenous Rap1 was precipitated from total cell lysates by the use of GST-RalGDS-RID and detected by immunoblotting using anti-Rap1 antibody. The amount of endogenous Rap1 in total cell lysates was monitored by anti-Rap1 antibody.

Additionally, the activation of plasma membrane-localized Rap1 upon TNF-α treatment was detected by pulldown assays, which was abrogated when the expression of M-Ras was down-regulated by RNAi (Figure 6E). Down-regulation of M-Ras by RNAi also inhibited the recruitment of RA-GEF-2 to the plasma membrane (Figure 6E). Importantly, TNF-α–induced Rap1 activation was completely inhibited in the plasma membrane of RA-GEF-2−/− splenocytes (Figure 6E). The chemokine stromal cell–derived factor-1 (SDF-1), like TNF-α, induces Rap1 activation and integrin-mediated cell adhesion in B-cells (McLeod et al., 2002). In marked contrast to those induced by TNF-α, SDF-1–dependent Rap1 activation and adhesion to ICAM-1 were totally unaffected by RA-GEF-2 knockout in splenocytes (Figure 6, F and G). Therefore, M-Ras and RA-GEF-2 are indeed involved in Rap1 activation, specifically downstream of the TNF-α receptor in mouse splenocytes.

DISCUSSION

Signaling for integrin activation in response to a diverse array of cytokines and chemokines has been shown to involve Rap1 (Bos et al., 2001; Kinashi, 2005). Evidence emerging from recent mouse genetics by the use of gene targeting also supports this notion. Primary hematopoietic cells isolated from the spleen and thymus of Rap1A-null mice showed diminished adhesion through LFA-1-ICAM-1 and VLA-4-fibronectin interactions, although these mice were viable and fertile (Duchniewicz et al., 2006). Rap1B is predominantly expressed in platelets and has been implicated in agonist-induced activation of the platelet-specific integrin αIIbβ3. Agonist-dependent aggregation of platelets from Rap1B-deficient mice was indeed reduced, and Rap1B-deficient mice were protected from arterial thrombosis (Chrzanowska-Wodnicka et al., 2005). Considering these literatures, Rap1 certainly exerts a pivotal role in lymphocyte adhesion in vivo as suggested by previous in vitro studies.

However, regulatory mechanisms for Rap1-mediated cell adhesion in vivo are only partly understood. Although diverse GEFs for Rap1 exist in mammalian cells, only CalDAG-GEFI (also known as RasGRP2) has been implicated in Rap1-mediated integrin activation through in vivo studies. CalDAG-GEFI contains calcium- and diacylglycerol-binding domains and thus acts downstream of phospholipase C (PLC) enzymes (Kawasaki et al., 1998b). Platelets from CalDAG-GEFI−/− mice are severely compromised in integrin-dependent aggregation and thrombus formation in response to multiple extracellular factors, including thrombin, thromboxane A2, and ADP, as a consequence of their inability to signal through CalDAG-GEFI to Rap1 (Crittenden et al., 2004). Therefore, CalDAG-GEFI is thought to be responsible for Rap1 activation downstream of diverse cell surface receptors that trigger platelet aggregation (Crittenden et al., 2004). Additionally, CalDAG-GEFI activates Rap1 in response to the “outside-in” signal evoked by integrin α2β1 (the collagen receptor), leading to cell adhesion mediated by the integrin αIIbβ3 (Bernardi et al., 2006).

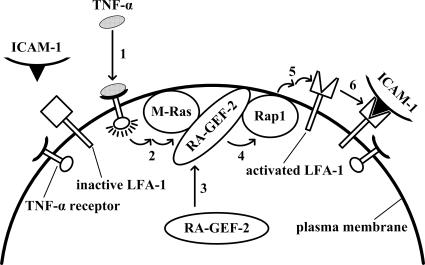

In macrophages, multiple inflammatory mediators, such as lipopolysaccharide, TNF-α, and platelet-activating factor, have been shown to activate the β2 integrin through the activation of Rap1 (Caron et al., 2000). CD31 (PECAM-1)-induced integrin activation also involves Rap1 in T-cells (Reedquist et al., 2000). Here, we have shown that M-Ras and RA-GEF-2 are involved in TNF-α–induced Rap1 activation, signaling that leads to LFA-1 activation in splenocytes (Figure 7). In contrast, other tested cytokines, such as IL-4, leukemia inhibitory factor, IL-7, IL-10, and IL-15, which trigger integrin-mediated adhesion, did not employ M-Ras and RA-GEF-2 as downstream signaling components (data not shown). Similarly, the chemokine SDF-1 does not require M-Ras for the induction of BAF/hLFA-1 cell adhesion (Katagiri et al., 2006). In the thymus, RA-GEF-2 was not necessary for TNF-α–induced, integrin-mediated adhesion, although expression levels of M-Ras and RA-GEF-2 were comparable to those in the spleen (Figures 5F and 6, A and D). Therefore, Rap1 activation mediated by M-Ras and RA-GEF-2 is thought to have an indispensable role in TNF-α signaling specifically in splenocytes, particularly splenic B-cells.

Figure 7.

Presumptive signaling pathway. On binding to the receptor (1), TNF-α activates M-Ras (2). The activated M-Ras recruits RA-GEF-2 from the cytoplasm to the plasma membrane (3), and RA-GEF-2 activates Rap1 in the plasma membrane (4) to induce LFA-1 activation (5) and adherence to ICAM-1 (6).

The activation of Rap1 independent of M-Ras and RA-GEF-2 may occur upon TNF-α stimulation in the thymus, although the mechanism remains obscure. If M-Ras acts downstream of the TNF-α receptor also in thymocytes, another RA-GEF family member RA-GEF-1 may possibly be involved in TNF-α stimulation of Rap1, because we have recently found that the RA domain of RA-GEF-1 also binds to the GTP-bound form of M-Ras in addition to that of Rap1 (unpublished results). Alternatively, Rap1-independent signaling may have a major role in TNF-α–induced adhesion in thymocytes. Recently, M-Ras null mice were generated, exhibiting no gross morphological defects at both anatomical and histological levels, further supporting the notion that M-Ras may have a highly specific role in TNF-α signaling in splenic B-cells (Nuñez Rodriguez et al., 2006.). In Drosophila embryonic macrophages, an ortholog of mammalian RA-GEFs, designated Dizzy, is responsible for Rap1–dependent integrin activation, leading to cell adhesion, cell shape change and cell migration (Huelsmann et al., 2006). Thus, RA-GEF-2 and Rap1-mediated integrin regulatory signaling may be conserved in eukaryotes. However, it remains unclear whether an M-Ras ortholog is involved upstream of Dizzy in Drosophila.

Upon the binding of its ligand, the TNF-α receptor undergoes homotrimerization, initiating the formation of a large signaling complex consisting of two classes of cytoplasmic adaptors: TNF receptor–associated factors (TRAFs) and death domain–containing molecules such as TRADD and FADD (Locksley et al., 2001; Aggarwal, 2003; Gilmore, 2006). Downstream of these adaptors, the IκB kinase complex phosphorylates IκB proteins, leading to their proteasomal degradation. In turn, NF-κB dimers are released and translocated to the nucleus, where transcription of an array of genes for adhesion molecules, chemokines, cytokines, and enzymes is induced. In addition to the NF-κB pathway, c-Jun N-terminal kinase and p38 mitogen–activated protein kinase cascades are activated in response to TNF-α stimulation. In contrast to these well-characterized signaling pathways, mechanisms for TNF-α–dependent M-Ras activation remain totally unknown. Indeed, no GEF that acts on M-Ras downstream of the TNF-α receptor has heretofore been identified. Intriguingly, conditional knockout of the TRAF2 gene in splenic B-cells was accompanied by significant splenomegaly similarly to RA-GEF-2 knockout (Grech et al., 2004). Thus, RA-GEF-2 may function downstream of TRAF2 in TNF-α signaling. The role of TRAF2 in the regulation of Rap1-dependent integrin activation will possibly be elucidated in future studies.

The RA-GEF-2–mediated signaling pathway described herein is interesting in that it involves two Ras family GTPases M-Ras and Rap1 in tandem, which are specifically linked by RA-GEF-2. TNF-α–activated M-Ras, which exists almost exclusively in the plasma membrane, recruited RA-GEF-2, which in turn activated Rap1. By this mechanism, a subset of Rap1 that is localized in the plasma membrane, in fact, became activated upon TNF-α stimulation (Figure 4E). Thus, tandemly arranged M-Ras and Rap1 may be primarily responsible for the subcellular region–specific regulation of downstream signaling. Another reported link between M-Ras and Rap1 is a GEF termed Repac/GFR/MR-GEF, which is most abundantly expressed in the brain (Rebhun et al., 2000). In contrast to RA-GEF-2, the ability of Repac/GFR/MR-GEF to promote Rap1 is inhibited by the activated form of M-Ras, and a physiological role of this signaling remains obscure. PLCε, a PLC isoform that harbors both RA and Rap1 GEF domains, also serves as a link between Ras family GTPases. Both Ras and Rap1 bind to the RA domain of PLCε in a GTP-dependent manner, thereby recruiting PLCε predominantly to the plasma membrane and the Golgi apparatus, respectively (Song et al., 2001). Rap1 GEF activity of PLCε contributes to prolonged activation of Rap1, specifically in the Golgi apparatus (Jin et al., 2001; Song et al., 2002). Therefore, PLCε also acts as a subcellular region–specific regulator of Rap1.

RAPL is identical to NORE1B (Tommasi et al., 2002), which directly binds to M-Ras in a GTP-dependent manner through its RA domain (Ehrhardt et al., 2001). However, mutationally or TNF-α–activated M-Ras did not transduce the signal directly to RAPL, but instead required RA-GEF-2 and Rap1 for the induction of LFA-1–dependent adhesion of both BAF3 cells and primary splenocytes as illustrated in this study. Although the mechanisms remain largely obscure, there may be some difference in the action of Rap1 and M-Ras on RAPL/NORE1B within the cell. Rap1, but not M-Ras, may exist in a microdomain of the plasma membrane, in which RAPL can regulate LFA-1, and thus the binding of RAPL to M-Ras, as observed in vitro, may not result in the recruitment of RAPL to the vicinity of LFA-1. As another possibility, the binding to M-Ras, unlike Rap1, may be insufficient for RAPL to become competent for the regulation of downstream molecules, such as Mst1. These possibilities will be examined in future studies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Masakazu Hattori and Nagahiro Minato for the SPA-1 cDNA and Jun-ichi Miyazaki for CAG-Cre mice. This investigation was supported by Grants-in-aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas “Cell and Tissue Disorganization in Cancer” and “Systems Genomics,” Scientific Research (B), and the 21st Century COE Research Program “Signaling Mechanisms by Protein Modification Reactions” from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan.

Abbreviations used:

- ES

embryonic stem

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GEF

guanine nucleotide exchange factor

- HA

hemagglutinin

- HBSS

Hanks' balanced salt solution

- ICAM-1

intercellular adhesion molecule 1

- IL

interleukin

- LFA-1

lymphocyte function–associated antigen 1

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PLC

phospholipase C

- PMA

phorbol myristate acetate

- RA

Ras/Rap1-associating

- RID

RalGDS-Ras–interacting domain

- RNAi

RNA interference

- SDF-1

stromal cell–derived factor-1

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor-α

- TRAF

TNF receptor–associated factors.

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E07-03-0250) on May 30, 2007.

REFERENCES

- Aggarwal B. B. Signalling pathways of the TNF superfamily: a double-edged sword. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2003;3:745–756. doi: 10.1038/nri1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi B., Guidetti G. F., Campus F., Crittenden J. R., Graybiel A. M., Balduini C., Torti M. The small GTPase Rap1b regulates the cross talk between platelet integrin α2β1 and integrin αIIbβ3. Blood. 2006;107:2728–2735. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-3023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos J. L., de Rooij J., Reedquist K. A. Rap1 signalling: adhering to new models. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001;2:369–377. doi: 10.1038/35073073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boussiotis V. A., Freeman G. J., Berezovskaya A., Barber D. L., Nadler L. M. Maintenance of human T cell anergy: blocking of IL-2 gene transcription by activated Rap1. Science. 1997;278:124–128. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5335.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caron E., Self A. J., Hall A. The GTPase Rap1 controls functional activation of macrophage integrin αMβ2 by LPS and other inflammatory mediators. Curr. Biol. 2000;10:974–978. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00641-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrzanowska-Wodnicka M., Smyth S. S., Schoenwaelder S. M., Fischer T. H., White G. C., 2nd Rap1b is required for normal platelet function and hemostasis in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:680–687. doi: 10.1172/JCI22973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook S. J., Rubinfeld B., Albert I., McCormick F. RapV12 antagonizes Ras-dependent activation of ERK1 and ERK2 by LPA and EGF in Rat-1 fibroblasts. EMBO J. 1993;12:3475–3485. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06022.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crittenden J. R., Bergmeier W., Zhang Y., Piffath C. L., Liang Y., Wagner D. D., Housman D. E., Graybiel A. M. CalDAG-GEFI integrates signaling for platelet aggregation and thrombus formation. Nat. Med. 2004;10:982–986. doi: 10.1038/nm1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Rooij J., Boenink N. M., van Triest M., Cool R. H., Wittinghofer A., Bos J. L. PDZ-GEF1, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor specific for Rap1 and Rap2. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:38125–38130. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.53.38125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Rooij J., Rehmann H., van Triest M., Cool R. H., Wittinghofer A., Bos J. L. Mechanism of regulation of the Epac family of cAMP-dependent RapGEFs. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:20829–20836. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001113200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Rooij J., Zwartkruis F. J., Verheijen M. H., Cool R. H., Nijman S. M., Wittinghofer A., Bos J. L. Epac is a Rap1 guanine-nucleotide-exchange factor directly activated by cyclic AMP. Nature. 1998;396:474–477. doi: 10.1038/24884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchniewicz M., Zemojtel T., Kolanczyk M., Grossmann S., Scheele J. S., Zwartkruis F. J. Rap1A-deficient T and B cells show impaired integrin-mediated cell adhesion. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006;26:643–653. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.2.643-653.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dustin M. L., Bivona T. G., Philips M. R. Membranes as messengers in T cell adhesion signaling. Nat. Immunol. 2004;5:363–372. doi: 10.1038/ni1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrhardt G. R., Korherr C., Wieler J. S., Knaus M., Schrader J. W. A novel potential effector of M-Ras and p21 Ras negatively regulates p21 Ras-mediated gene induction and cell growth. Oncogene. 2001;20:188–197. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X., Satoh T., Liao Y., Song C., Hu C. D., Kariya K., Kataoka T. Identification and characterization of RA-GEF-2, a Rap guanine nucleotide exchange factor that serves as a downstream target of M-Ras. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:42219–42225. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105760200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnotel R., Monboisse J.-C., Randoux A., Haye B., Borel J. P. The binding of type I collagen to lymphocyte function-associated antigen (LFA) 1 integrin triggers the respiratory burst of human polymorphonuclear neutrophils. Role of calcium signaling and tyrosine phosphorylation of LFA 1. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:27495–27503. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.46.27495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore T. D. Introduction to NF-κB: players, pathways, perspectives. Oncogene. 2006;25:6680–6684. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotoh T., et al. Identification of Rap1 as a target for the Crk SH3 domain-binding guanine nucleotide-releasing factor C3G. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1995;15:6746–6753. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.12.6746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grech A. P., Amesbury M., Chan T., Gardam S., Basten A., Brink R. TRAF2 differentially regulates the canonical and noncanonical pathways of NF-κB activation in mature B cells. Immunity. 2004;21:629–642. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huelsmann S., Hepper C., Marchese D., Knoll C., Reuter R. The PDZ-GEF dizzy regulates cell shape of migrating macrophages via Rap1 and integrins in the Drosophila embryo. Development. 2006;133:2915–2924. doi: 10.1242/dev.02449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichiba T., Hoshi Y., Eto Y., Tajima N., Kuraishi Y. Characterization of GFR, a novel guanine nucleotide exchange factor for Rap1. FEBS Lett. 1999;457:85–89. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01012-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin T. G., Satoh T., Liao Y., Song C., Gao X., Kariya K., Hu C. D., Kataoka T. Role of the CDC25 homology domain of phospholipase Cε in amplification of Rap1-dependent signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:30301–30307. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103530200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katagiri K., Hattori M., Minato N., Irie S., Takatsu K., Kinashi T. Rap1 is a potent activation signal for leukocyte function-associated antigen 1 distinct from protein kinase C and phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20:1956–1969. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.6.1956-1969.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katagiri K., Imamura M., Kinash T. Spatiotemporal regulation of the kinase Mst1 by binding protein RAPL is critical for lymphocyte polarity and adhesion. Nat. Immunol. 2006;7:919–928. doi: 10.1038/ni1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katagiri K., Maeda A., Shimonaka M., Kinashi T. RAPL, a Rap1-binding molecule that mediates Rap1-induced adhesion through spatial regulation of LFA-1. Nat. Immunol. 2003;4:741–748. doi: 10.1038/ni950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katagiri K., Ohnishi N., Kabashima K., Iyoda T., Takeda N., Shinkai Y., Inaba K., Kinashi T. Crucial functions of the Rap1 effector molecule RAPL in lymphocyte and dendritic cell trafficking. Nat. Immunol. 2004;5:1045–1051. doi: 10.1038/ni1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki T., Choudhry M. A., Schwacha M. G., Bland K. I., Chaudry I. H. Lidocaine depresses splenocyte immune functions following trauma-hemorrhage in mice. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2006;291:C1049–C1055. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00252.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki H., Springett G. M., Mochizuki N., Toki S., Nakaya M., Matsuda M., Housman D. E., Graybiel A. M. A family of cAMP-binding proteins that directly activate Rap1. Science. 1998a;282:2275–2279. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5397.2275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki H., et al. A Rap guanine nucleotide exchange factor enriched highly in the basal ganglia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998b;95:13278–13283. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinashi T. Intracellular signalling controlling integrin activation in lymphocytes. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005;5:546–559. doi: 10.1038/nri1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama H., Sugimoto Y., Matsuzaki T., Ikawa Y., Noda M. A ras-related gene with transformation suppressor activity. Cell. 1989;56:77–84. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90985-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafuente E. M., van Puijenbroek A. A., Krause M., Carman C. V., Freeman G. J., Berezovskaya A., Constantine E., Springer T. A., Gertler F. B., Boussiotis V. A. RIAM, an Ena/VASP and Profilin ligand, interacts with Rap1-GTP and mediates Rap1-induced adhesion. Dev. Cell. 2004;7:585–595. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Y., et al. RA-GEF, a novel Rap1A guanine nucleotide exchange factor containing a Ras/Rap1A-associating domain, is conserved between nematode and humans. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:37815–37820. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.53.37815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Y., Satoh T., Gao X., Jin T. G., Hu C. D., Kataoka T. RA-GEF-1, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor for Rap1, is activated by translocation induced by association with Rap1·GTP and enhances Rap1-dependent B-Raf activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:28478–28483. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101737200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locksley R. M., Killeen N., Lenardo M. J. The TNF and TNF receptor superfamilies: integrating mammalian biology. Cell. 2001;104:487–501. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00237-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod S. J., Li A. H., Lee R. L., Burgess A. E., Gold M. R. The Rap GTPases regulate B cell migration toward the chemokine stromal cell-derived factor-1 (CXCL12): potential role for Rap2 in promoting B cell migration. J. Immunol. 2002;169:1365–1371. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.3.1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller K. L., Daniels M. A., Felthauser A., Kao C., Jameson S. C., Shimizu Y. Cutting edge: LFA-1 integrin-dependent T cell adhesion is regulated by both ag specificity and sensitivity. J. Immunol. 2004;173:2222–2226. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.4.2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuñez Rodriguez N., Lee I. N., Banno A., Qiao H. F., Qiao R. F., Yao Z., Hoang T., Kimmelman A. C., Chan A. M. Characterization of R-Ras3/M-Ras null mice reveals a potential role in trophic factor signaling. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006;26:7145–7154. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00476-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtsuka T., Hata Y., Ide N., Yasuda T., Inoue E., Inoue T., Mizoguchi A., Takai Y. nRap GEP: a novel neural GDP/GTP exchange protein for rap1 small G protein that interacts with synaptic scaffolding molecule (S-SCAM) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999;265:38–44. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtsuka T., Shimizu K., Yamamori B., Kuroda S., Takai Y. Activation of brain B-Raf protein kinase by Rap1B small GTP-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:1258–1261. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.3.1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada T., Hu C. D., Jin T. G., Kariya K., Yamawaki-Kataoka Y., Kataoka T. The strength of interaction at the Raf cysteine-rich domain is a critical determinant of response of Raf to Ras family small GTPases. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:6057–6064. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.9.6057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peirce M. J., Wait R., Begum S., Saklatvala J., Cope A. P. Expression profiling of lymphocyte plasma membrane proteins. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2004;3:56–65. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M300064-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham N., Cheglakov I., Koch C. A., de Hoog C. L., Moran M. F., Rotin D. The guanine nucleotide exchange factor CNrasGEF activates ras in response to cAMP and cGMP. Curr. Biol. 2000;10:555–558. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00473-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebhun J. F., Castro A. F., Quilliam L. A. Identification of guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) for the Rap1 GTPase. Regulation of MR-GEF by M-Ras-GTP interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:34901–34908. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005327200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reedquist K. A., Ross E., Koop E. A., Wolthuis R. M., Zwartkruis F. J., van Kooyk Y., Salmon M., Buckley C. D., Bos J. L. The small GTPase, Rap1, mediates CD31-induced integrin adhesion. J. Cell Biol. 2000;148:1151–1158. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.6.1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai K., Miyazaki J. A transgenic mouse line that retains Cre recombinase activity in mature oocytes irrespective of the cre transgene transmission. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997;237:318–324. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebzda E., Bracke M., Tugal T., Hogg N., Cantrell D. A. Rap1A positively regulates T cells via integrin activation rather than inhibiting lymphocyte signaling. Nat. Immunol. 2002;3:251–258. doi: 10.1038/ni765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song C., Hu C. D., Masago M., Kariya K., Yamawaki-Kataoka Y., Shibatohge M., Wu D., Satoh T., Kataoka T. Regulation of a novel human phospholipase C, PLCε, through membrane targeting by Ras. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:2752–2757. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008324200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song C., Satoh T., Edamatsu H., Wu D., Tadano M., Gao X., Kataoka T. Differential roles of Ras and Rap1 in growth factor-dependent activation of phospholipase Cε. Oncogene. 2002;21:8105–8113. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stork P. J., Dillon T. J. Multiple roles of Rap1 in hematopoietic cells: complementary versus antagonistic functions. Blood. 2005;106:2952–2961. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tommasi S., Dammann R., Jin S. G., Zhang X. F., Avruch J., Pfeifer G. P. RASSF3 and NORE1, identification and cloning of two human homologues of the putative tumor suppressor gene RASSF1. Oncogene. 2002;21:2713–2720. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukamoto N., Hattori M., Yang H., Bos J. L., Minato N. Rap1 GTPase-activating protein SPA-1 negatively regulates cell adhesion. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:18463–18469. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.26.18463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vossler M. R., Yao H., York R. D., Pan M. G., Rim C. S., Stork P. J. cAMP activates MAP kinase and Elk-1 through a B-Raf- and Rap1-dependent pathway. Cell. 1997;89:73–82. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80184-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D., Tadano M., Edamatsu H., Masago-Toda M., Yamawaki-Kataoka Y., Terashima T., Mizoguchi A., Minami Y., Satoh T., Kataoka T. Neuronal lineage-specific induction of phospholipase Cε expression in the developing mouse brain. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2003;17:1571–1580. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita S., Mochizuki N., Ohba Y., Tobiume M., Okada Y., Sawa H., Nagashima K., Matsuda M. CalDAG-GEFIII activation of Ras, R-ras, and Rap1. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:25488–25493. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003414200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]