Abstract

Crossovers produced by homologous recombination promote accurate chromosome segregation in meiosis and are controlled such that at least one forms per chromosome pair and multiple crossovers are widely spaced. Recombination initiates with an excess number of double-strand breaks made by Spo11 protein. Thus, crossover control involves a decision by which some breaks give crossovers while others follow a predominantly noncrossover pathway(s). To understand this decision, we examined recombination when breaks are reduced in yeast spo11 hypomorphs. We find that crossovers tend to be maintained at the expense of noncrossovers and that genomic loci differ in expression of this “crossover homeostasis.” These findings define a previously unsuspected manifestation of crossover control, i.e., that the crossover/noncrossover ratio can change to maintain crossovers. Our results distinguish between existing models of crossover control and support the hypothesis that an obligate crossover is a genetically programmed event tied to crossover interference.

Keywords: Spo11, meiosis, recombination, crossover interference, chiasma

Introduction

Crossing-over during meiosis helps to establish physical connections (chiasmata) between homologs that promote accurate segregation at the first meiotic division (Page and Hawley, 2003). Chromosomes that fail to cross over also frequently fail to disjoin properly, yielding aneuploid gametes. Not surprisingly then, crossover formation is tightly controlled to prevent the occurrence of non-exchange chromosomes (Bishop and Zickler, 2004; Hillers, 2004; Kleckner et al., 2004).

Crossover control has several manifestations in most organisms. First, the distribution of crossovers among chromosomes is not random. Rather, the average number of crossovers per chromosome pair is extremely low (often as low as 1–2), yet non-exchange chromosomes are rare. The tendency toward guaranteed crossover formation is often referred to as the obligate crossover or chiasma (Jones, 1984). A second manifestation of crossover control is that crossovers are distributed nonrandomly along chromosomes when two or more occur on the same chromosome pair: a crossover in one region makes it less likely that another will be found nearby. This phenomenon, first described nearly a century ago (Muller, 1916; Sturtevant, 1915), is called crossover interference (reviewed in Hillers, 2004; Kleckner et al., 2004). The strength of interference diminishes as a function of distance along the chromosome, but the distances involved vary substantially from organism to organism, from tens of kb in S. cerevisiae (Malkova et al., 2004) to tens of Mb or greater in mammals (e.g., Broman and Weber, 2000).

The net result of crossover control is that each chromosome gets at least one crossover despite a low average number of crossovers per chromosome, and multiple crossovers on the same chromosome tend to be evenly and widely spaced. It is generally thought that these aspects of crossover control reflect a single underlying mechanism, although this remains to be formally proven (Hillers, 2004; Kleckner et al., 2004).

Crossovers are generated by homologous recombination initiated by DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) formed by the topoisomerase-like Spo11 protein (Keeney, 2001). There are more DSBs than crossovers, in some cases substantially more (≥10-fold) (e.g., Moens et al., 2002). DSBs that do not become crossovers are repaired to give noncrossovers instead. DSBs interfere with formation of adjacent DSBs much less (if at all) than crossovers interfere with one another (e.g., Malkova et al., 2004). Thus, integral to crossover interference is a “decision” process by which a subset of randomly distributed recombination precursors (DSBs or later stage intermediates) enters a pathway that culminates in crossover formation, while all other precursors follow a pathway(s) that generates primarily noncrossover products (most likely with a few noninterfering crossovers) (Allers and Lichten, 2001; Borner et al., 2004; Copenhaver et al., 2002; Stahl et al., 2004). This decision occurs early, at or prior to the appearance of the first stable strand exchange intermediates (reviewed in Bishop and Zickler, 2004).

How one precursor over another is chosen for a crossover fate is not well understood. One possibility is that a subset of precursors is selected from the available pool and directed toward a crossover fate, with excess precursors—no matter how many or how few—resolved by a default, predominantly noncrossover pathway. This model would fit well with the obligate crossover as a programmed event that is mechanistically linked to interference. This scenario is also consistent with models in which crossover designation at a given site results in propagation of a physical signal that inhibits crossover formation nearby (see Discussion).

This model makes a clear prediction about what would happen if fewer DSBs were made, namely, that crossover numbers should tend to be maintained at the expense of noncrossovers. We tested this prediction in S. cerevisiae using a spo11 allelic series to vary Spo11 activity in vivo (Henderson and Keeney, 2004). We show here that crossovers indeed tend to be maintained at the expense of noncrossovers, such that the crossover/noncrossover ratio changes. These findings give insight into the fundamental logic of the interference decision and distinguish between existing mechanistic models of crossover control.

Results

A SPO11 allelic series to modulate double-strand break frequencies

To reduce DSBs throughout the genome, we used a previously described series of spo11 mutants (Diaz et al., 2002; Henderson and Keeney, 2004). The first expresses Spo11 tagged at its C-terminus with three repeats of the HA epitope and a hexahistidine sequence (spo11-HA3His6, hereafter spo11-HA for simplicity). The tag reduces DSB frequency for unknown reasons. DSBs are further reduced in strains heterozygous for spo11-HA and a tagged allele with the catalytic tyrosine altered to phenylalanine (spo11-Y135F-HA3His6, hereafter spo11yf-HA). DSBs are reduced even further in strains homozygous for mutation of another putative active site residue (spo11-D290A-HA3His6, hereafter spo11da-HA). Spo11 activity was quantified by direct measurement of DSBs in genomic DNA and by frequencies of intragenic recombination at the HIS4LEU2 and ARG4 loci in return-to-growth assays (Figure 1A and Table 1). Based on the direct DSB measurements, the mutants formed ∼80%, ∼30%, and ∼20% of wild-type DSB levels. There was broad agreement between different genomic regions, indicating that this allelic series titrates Spo11 activity in a fairly uniform manner across the genome (although there are some variations, discussed further below).

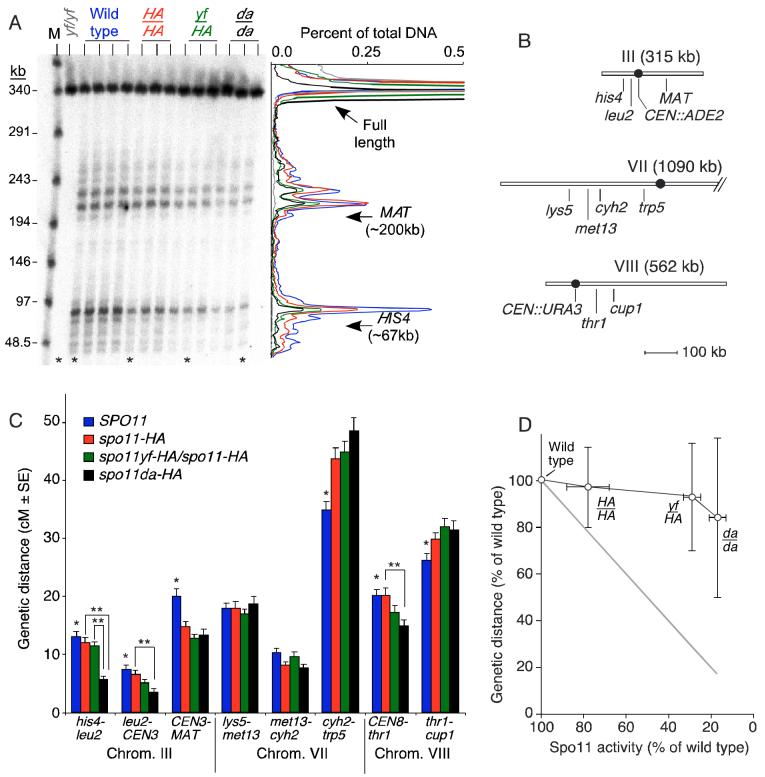

Figure 1.

Reduction of DSBs does not decrease the number of crossovers in parallel.

(A) Effects of a SPO11 allelic series on DSBs on chromosome III. High molecular weight genomic DNA was isolated from 3 or 4 independent cultures of rad50S strains carrying the indicated SPO11 genotype (HA, spo11-HA; yf, spo11yf-HA; da, spo11da-HA). DNA was separated by pulsed-field electrophoresis and analyzed by Southern blotting and indirect end-labeling with a probe from the left end of chromosome III. M, lambda concatemer size markers. The plot on the right shows traces of representative lanes (asterisks), color coded as above the autoradiograph.

(B) Genetic intervals on chromosomes III, VII, and VIII.

(C) Genetic distances for wild type and three spo11 mutants. Error bars are standard errors. A single asterisk indicates intervals where wild type was significantly different from at least one mutant (p<0.017, G test). A double asterisk denotes a statistically significant difference between spo11 mutants (p<0.017, G test).

(D) Nonlinear relationship between DSBs and crossovers. Y-axis values are means ± s.d. for all eight intervals examined. X-axis values are means ± s.d. for DSB measurements on all three chromosomes (Table 1). The gray line is as expected for a linear relationship.

Table 1.

Reduced DSB formation in a series of spo11 hypomorphic mutants.

| Result for each SPO11 genotype (% of wild-type value) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

spo11-HA |

spo11yf-HA |

spo11da-HA |

||

| Analytical method | Wild type |

spo11-HA |

spo11-HA |

spo11da-HA |

| A. rad50S DSBs on pulsed-field gels, 32°C (% of DNA) | ||||

| Chromosome III | 50.7 ± 2.3 (100) | 34.9 ± 1.1 (69) | 14.8 ± 2.7 (29) | 9.4 ± 2.7 (19) |

| Chromosome VII | 60.9 ± 2.2 (100) | 45.6 ± 4.4 (75) | 19.2 ± 4.1 (32) | 11.4 ± 2.6 (19) |

| Chromosome VIII | 54.9 ± 2.6 (100) | 49.0 ± 2.0 (89) | 13.6 ± 3.6 (25) | 6.9 ± 3.9 (13) |

| Relative activity (% of wild type)* | ≡ 100 | 78 ± 10 | 29 ± 4 | 17 ± 4 |

| B. Return to growth (prototroph frequency, per 1000 viable cells) | ||||

| his4BLEU2/his4XLEU2 (32°C) | 15.0 ± 8.1 (100) | 8.0 ± 2.1 (53) | 6.6 ± 1.5 (44) | 3.4 ± 0.8 (22) |

| arg4-Nsp/arg4-Bgl (30°C) | 28.0 ± 4.4 (100) | 23.8 ± 2.6 (85) | 13.1 ± 6.5 (47) | 0.95 ± 0.31 (3.4) |

Spo11 activity was measured by Southern blot of genomic DNA and by return-to-growth assays for the indicated chromosomes or loci (mean ± s.d. for ≥3 independent cultures).

Mean ± s.d. of the percent of wild type, obtained by averaging results for the three chromosomes.

Crossover homeostasis: reducing DSBs does not reduce crossovers in parallel

To examine the relationship between crossover and DSB frequencies, we constructed strains that differed in the SPO11 genotype and carried heterozygous markers to measure crossover frequencies in eight intervals spanning a total of 484 kb on three chromosomes (Figure 1B). These chromosomes span a range of sizes from the third smallest of the yeast genome to the third largest. Crossover formation and interference have been extensively studied in these regions (e.g., de los Santos et al., 2003; Malkova et al., 2004). Segregation of the markers was analyzed in ≥750 four-spore-viable tetrads for each SPO11 genotype, providing a measure of genetic distances between markers expressed in centimorgans (cM), where 1 cM corresponds to a crossover frequency of 1%. Figure 1C summarizes genetic distances in the four SPO11 genotypes; full segregation patterns and statistical tests are in Supplemental Tables 1 and 2. In four of five intervals on the larger chromosomes (VII and VIII), there was no statistically significant decrease in crossover frequency in the mutants compared to wild type or one another. In the fifth interval (CEN8::URA3 to thr1) and in all three intervals on chromosome III, crossovers were significantly reduced for at least one of the mutants (p<0.017, G test), but always less than the reduction in DSBs. For example, crossovers were reduced ∼2-fold in the his4 to leu2 interval in spo11da-HA vs. wild type, as compared to the ∼5-fold reduction in DSBs. Surprisingly, the cyh2-trp5 and thr1-cup1 intervals had small but significant increases in crossover frequencies in some of the spo11 mutants. This pattern may reflect the fact that tetrad dissection for wild type was carried out in a separate laboratory. Similar small variations were reported in another recent study (Malkova et al., 2004). This issue does not affect conclusions drawn here because the overall pattern holds even if the three spo11 mutants are considered separately.

Chromosome segregation defects were seen only in the more defective spo11 mutants, as revealed by spore viability patterns (Supplemental Table 3). Wild type yielded 95.2% viable spores, with 917 four-spore-viable tetrads out of 1049 dissected (87%). The spo11-HA strain yielded similar numbers (94.0% viable spores, 87% four-spore-viable tetrads), indicating that the ∼20% reduction in DSBs in this strain had little or no effect on the efficiency of meiotic chromosome segregation. In contrast, spore viabilities were reduced in spo11yf-HA/spo11-HA (75.9% viable spores, 62% four-spore-viable tetrads) and spo11da-HA strains (69.7% viable spores, 56% four-spore-viable tetrads). Both strains had increased frequencies of two-spore-and zero-spore-viable tetrads, a hallmark of homolog nondisjunction at the first division (Supplemental Table 3). Thus, there appears to be a threshold between ∼80% and ∼30% of normal DSBs below which there is insufficient recombination to support the normal efficiency of chromosome segregation.

Our analysis reveals a nonlinear quantitative relationship between DSBs and crossovers (Figure 1D), from which we infer that crossover numbers tend to be maintained despite reduction in the number of initiation events. We refer to this phenomenon as crossover homeostasis. Importantly, this relationship was observed even in the spo11-HA strain, which had normal spore viability. Thus, quantitative differences between crossovers and DSBs cannot be ascribed solely to selection bias imposed by analysis of four-spore-viable tetrads (see Discussion).

Crossover numbers are maintained at the expense of noncrossovers

Since crossover numbers remained high when DSBs were reduced, it follows that a smaller proportion of DSBs were being repaired as noncrossovers, i.e., that the ratio of crossovers to noncrossovers was altered. We were unable to assess this conclusion directly from the tetrad data because there were not enough gene conversion tetrads to provide a statistically significant measure of relative crossover and noncrossover frequencies (Supplemental Table 4 and data not shown). A recombination reporter was therefore designed to measure the frequencies of both crossover and noncrossover events at a single locus. ARG4 is a natural meiotic recombination hotspot within one of the intervals on chromosome VIII analyzed above (Figure 2A) (Nicolas et al., 1989). Meiotic DSBs form frequently at a site ∼185 bp upstream of the ARG4 coding region (Figure 2B). We used two arg4 alleles: arg4-Nsp mutated at an NspHI restriction site at the initiation codon and arg4-Bgl mutated at a BglII site near the 3′ end of the gene (Figure 2B) (Nicolas et al., 1989). These alleles were flanked by two markers used in the tetrad analysis above: the URA3 gene integrated near the centromere and a mutation at THR1. NdeI restriction site polymorphisms were also introduced closer to ARG4. A diploid heterozygous for these arg4 mutations cannot grow on medium lacking arginine, but a functional ARG4 gene can be generated by recombination. Nearly all Arg+ progeny arise from gene conversion, with or without associated crossover.

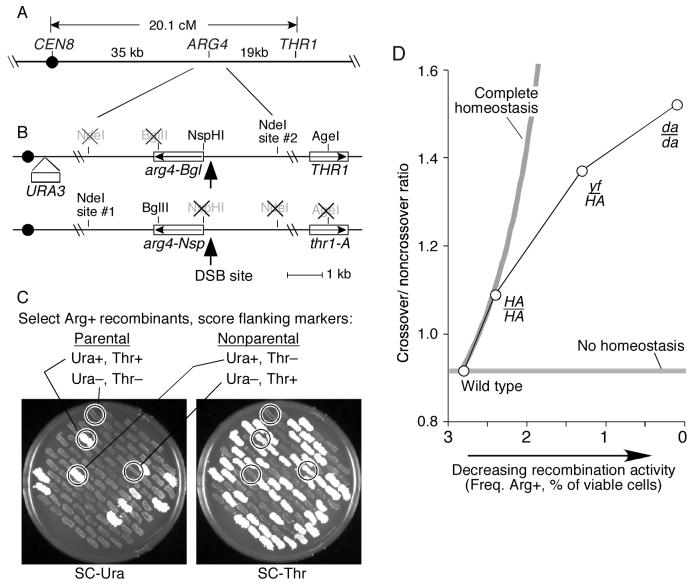

Figure 2.

Crossover homeostasis occurs at the expense of noncrossovers.

(A, B) Maps of the assay region showing configuration of the arg4 alleles and flanking markers.

(C) Random spore analysis of recombination at ARG4. Random spores from strains heterozygous for arg4-Nsp and arg4-Bgl were plated on SC-arginine to select for Arg+ recombinants. Spore clone colonies were patched onto SC-arginine plates, then replica-printed onto SC-uracil and SC-threonine to score flanking markers. Examples of parental and nonparental clones are indicated.

(D) Reduced Spo11 activity is accompanied by an increased crossover/noncrossover ratio. The ratio of crossovers to noncrossovers for Arg+ recombinants was calculated from the random spore data after correcting for incidental crossovers (see text). Gray lines show expected patterns for no homeostasis and for complete homeostasis. The curve for complete homeostasis was calculated assuming that 70% of crossovers in wild type were interference sensitive, with the remainder not subject to crossover homeostasis. Similar curves are obtained for interfering crossover values of 60-85% (data not shown).

The effects of the spo11 mutations on conversion frequencies at ARG4 were first determined. As expected, the spo11 mutants yielded fewer Arg+ recombinants than wild type (Table 1). The results were similar to the effect of these mutations elsewhere in the genome, except for spo11da-HA, which had a more severe effect on frequencies of conversions and DSBs at ARG4 than at most other genomic regions (Table 1 and data not shown).

To measure what fraction of Arg+ recombinants had exchanged the flanking markers, random spores were plated on medium lacking arginine, then Arg+ spore clones were scored for the configuration of flanking markers by replica-plating on medium lacking uracil or threonine (Figure 2C). In the SPO11+ strain, 54.8% of Arg+ recombinants had a nonparental configuration of the flanking markers, and this fraction increased progressively in the three spo11 mutants (Table 2). This was the expected pattern for crossover homeostasis: if a greater fraction of recombination events are crossover-associated in the spo11 mutants, then a greater fraction of Arg+ recombinants should have nonparental flanking markers. However, when the flanking markers have been exchanged, the exchange could have arisen from the same recombination event that gave the Arg+ conversion, or could have arisen from an independent event elsewhere in the interval. The latter is referred to as an incidental exchange, and could complicate interpretation of the results if it occurred frequently. We therefore analyzed the configuration of the NdeI restriction site polymorphisms closely flanking ARG4 (Figure 2B). A crossover associated with the Arg+ conversion would exchange the NdeI polymorphisms along with the more distant markers, whereas incidental exchange outside the region between the NdeI sites would leave a parental NdeI configuration (see Supplemental Figure 1 for more detail).

Table 2.

Random spore analysis of recombination at the ARG4 locus.

| Number of spore clones (% of total) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parental |

Nonparental |

||||||

| Genotype | Ura+ Thr+ | Ura− Thr− | Ura− Thr+ | Ura+ Thr− | Total | % Nonparental | Significance |

| Wild type | 134 (4.2) | 1322 (41.1) | 1525 (47.4) | 239 (7.4) | 3220 | 54.8 | |

| HA/HA | 159 (4.8) | 1186 (36.0) | 1754 (53.3) | 194 (5.9) | 3293 | 59.2 | p = 0.0004 |

| yf-HA/HA | 149 (4.1) | 1120 (30.6) | 2207 (60.4) | 180 (4.9) | 3656 | 65.3 | p = 1 × 10−7 |

| da-HA/da-HA | 130 (5.5) | 633 (26.8) | 1534 (64.8) | 69 (2.9) | 2366 | 67.8 | p = 3 × 10−7 |

Random spores from strains carrying the recombination reporter diagrammed in Figure 2 and the indicated SPO11 genotypes were plated on medium lacking arginine to select for Arg+ recombinants, then the configuration of flanking markers was scored. Data were pooled from three independent cultures of each strain (≥661 spore clones per culture). Statistical significance was evaluated by G test for the distribution of spore types for each strain compared to the strain listed above it. The majority (∼90%) of the recombinants with a parental configuration of flanking markers were Ura− and Thr−. This is the expected pattern because of the polarity of gene conversion at this locus (Nicolas et al., 1989). Specifically, in recombination initiated by a DSB, the broken chromosome is the recipient of genetic information. The arg4-Nsp mutation is closer to the DSB site (Figure 2B), so conversion of this mutation to wild type accounts for most of the noncrossover Arg+ recombinants. Thus, Arg+ progeny arising from a noncrossover event will inherit the parental configuration from the original arg4-Nsp chromosome. The same feature of the locus accounts for the fact that the majority (∼90%) of the Arg+ spores with a nonparental configuration were Ura− Thr+.

For the SPO11+ strain, 77 clones of the majority nonparental class (Ura− Thr+) were scored. Of these, 70 (91%) also had a nonparental NdeI configuration, consistent with a single crossover associated with conversion at ARG4 (Supplemental Table 5). In the spo11yfHA/spo11-HA mutant, 86 of 89 Ura− Thr+ clones analyzed (97%) also had a nonparental configuration of NdeI sites, not significantly different from wild type (p>0.15) (Supplemental Table 5). Of the remaining Ura− Thr+ clones from both strains, nearly all had a marker configuration consistent with a noncrossover conversion of arg4-Nsp plus a single incidental exchange (Supplemental Table 5 and Supplemental Figure 1). Incidental exchanges played a more significant role in generating the minority (Ura+ Thr−) class of nonparental Arg+ recombinants, because only ∼70% had the expected pattern for a single exchange associated with the Arg+ conversion for both SPO11 (6 of 9 clones analyzed) and spo11yf-HA/spo11-HA (5 of 7 clones) (Supplemental Table 5 and Supplemental Figure 1). These findings indicate that incidental exchanges accounted for only ∼12% of nonparental Arg+ clones. More importantly, this fraction varied little with SPO11 genotype, ruling out the possibility that the differences we observed in the spo11 mutants were caused by changes in the contribution of incidental exchanges.

The fraction of Arg+ conversions that are crossover-associated can be estimated by correcting for the observed frequency of incidental exchanges (i.e., scoring 10% of the Ura− Thr+ clones and 30% of Ura+ Thr− clones as noncrossover even though they had an exchange). (Incidental exchanges could also “erase” crossovers that were associated with Arg+ conversion, but such events are very infrequent because they require ≥2 crossovers in the small interval between CEN8::URA3 and THR1.) From this estimate, 47.8% (1539/3220) of Arg+ conversions were crossover-associated in wild type, and this fraction increased to 52.1% (1715/3293) in spo11-HA/spo11-HA, to 58.8% (2112/3656) in spo11yf-HA/spo11-HA, and to 60.4% (1429/2366) in spo11da-HA/spo11da/HA. These increases were statistically significant (p≤0.0004, Fisher's exact test mid-p). Thus, decreased DSB frequencies cause an increase in the ratio of crossovers to noncrossovers (Figure 2D), confirming that crossover numbers tend to be maintained at the expense of noncrossovers.

Interestingly, these results also reveal that crossover homeostasis does not provide an absolute guarantee that a DSB will give rise to a crossover. If crossover homeostasis were completely efficient, the crossover-noncrossover ratio should increase rapidly with decreasing DSB frequency, reaching a situation in which every recombination event yields a crossover. The observed crossover-noncrossover ratios diverge substantially from this expectation for the more severely DSB-defective strains (Figure 2D). Possible reasons for this behavior are addressed in the Discussion.

Crossover interference is maintained when DSB frequencies are reduced

To determine whether reduced DSBs affected crossover interference, we examined the tetrad data for the SPO11 allelic series using the method described by Malkova et al. (2004) (Supplemental Table 6). Briefly, the tetrads were divided into two groups based on presence (tetratypes and nonparental ditypes) or absence (parental ditypes) of a detectable crossover within a reference interval. Then, for each group we assessed crossover frequency in an adjacent interval. If a crossover in the reference interval is accompanied by significantly less recombination in an adjacent interval, then we can conclude that crossover interference extends from one interval to the other. The process was repeated for each SPO11 genotype, using each of the eight intervals individually as the reference (Supplemental Table 6). For example, when there was no detectable crossover in the lys5-met13 interval, the adjacent met13-cyh2 interval had a genetic length of 13.6 cM, but when there was a crossover in the lys5-met13 interval, the met13-cyh2 distance was only 4.3 cM (Supplemental Table 6B). As a rough estimate of the strength of interference, we determined the ratio of the two genetic distances (i.e., 4.3/13.6 = 0.32) (Figure 3 and Supplemental Table 6). The smaller the ratio, the greater the apparent strength of interference. This “interference ratio” is different from but analogous to another measure of interference, the coefficient of coincidence.

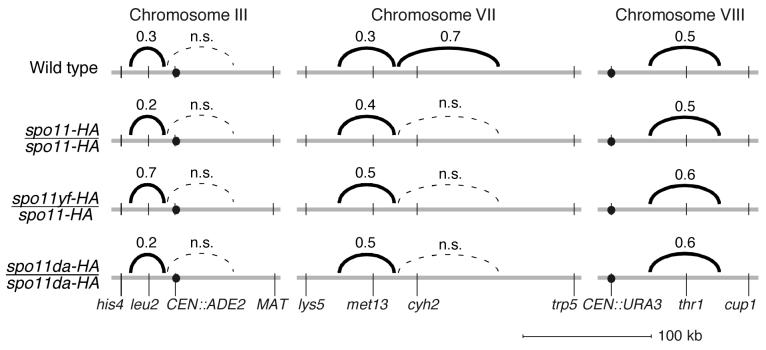

Figure 3.

Crossover interference is maintained when Spo11 activity is reduced. Interference was assessed by comparing the genetic distance in an interval with vs. without a crossover in the adjacent interval (see text for details). Solid black arcs connect adjacent intervals that showed significant evidence for interference. Numbers above the arcs are the average of interference ratios for each interval pair. The smaller the number, the stronger the interference. Dashed lines indicate adjacent intervals for which no statistically significant evidence for interference was observed (“n.s.”, not significant).

In wild type, interference was observed between several adjacent intervals (interference ratios of 0.3–0.5): between his4-leu2 and leu2-CEN3 on chromosome III, between lys5-met13 and met13-cyh2 on chromosome VII, and between CEN8-thr1 and thr1-cup1 on chromosome VIII (Figure 3 and Supplemental Table 6). The patterns on chromosome VII were comparable to those from an earlier study (Malkova et al., 2004). No interference was detected between CEN3-MAT on the right arm of chromosome III and either of the intervals on the left arm. It is possible that the physical distances are simply too large to detect interference (CEN3-MAT is ∼90 kb).

Importantly, in nearly all cases where interference was seen in the wild type strain, it was also observed at comparable levels in each of the spo11 mutants (Figure 3 and Supplemental Table 6). The apparent exception was for comparisons involving the cyh2-trp5 interval on chromosome VII, where there was evidence for weak interference in wild type but not in the mutants (Figure 3). This interval is very large (>130 kb, ≥35 cM; Figure 1B, C), so the size may make it difficult to detect interference with adjacent intervals. (This interpretation is consistent with a study with more closely spaced markers in this region (Malkova et al., 2004)). Indeed, additional analysis (see below) reveals evidence for interference within this interval in wild type and the spo11 mutants.

Interference was not stronger in the spo11 mutants than in wild type as judged by the interference ratio; if anything, there may have been slight weakening in some cases (Figure 3). Also, intervals that showed no evidence for interference in wild type did not begin to show interference in the mutants (Figure 3 and Supplemental Table 6), indicating that interference does not extend over greater distances in the spo11 mutants.

Interference was also assessed within each interval by comparing the number of observed nonparental ditypes (double crossovers involving all four chromatids) to the number expected if there were no interference (Papazian, 1952). Nearly all of the intervals showed significant evidence for interference in wild type and the spo11 mutants (Supplemental Table 7). The exceptions, leu2-CEN3 and met13-cyh2, were too small for this analysis. Importantly, there was strong evidence for interference within the cyh2-trp5 interval and, consistent with results for other intervals, the strength of interference (judged from the magnitude of the nonparental ditype ratios) was similar in wild type and spo11 mutants (Supplemental Table 7).

We conclude that reducing Spo11 activity within the range examined here has little or no effect on either the strength of crossover interference or the distance over which interference can be detected. Thus, interference within a chromosomal region appears to be largely independent of the number of DSBs in that region. These findings help discriminate between existing models for crossover interference (see Discussion).

Locus-specific differences in crossover homeostasis

It appears that different genomic regions differ in the ability to show crossover homeostasis (Figure 1C). A more striking example of locus-specific variation came from analysis of the HIS4LEU2 hotspot. This locus consists of sequences from the LEU2 region inserted near the HIS4 gene and contains a strong hotspot for DSB formation (Cao et al., 1990). We developed a two-dimensional electrophoresis assay to detect both crossovers and noncrossover gene conversions, taking advantage of a modified HIS4LEU2 in which most cells incur a DSB at a single site (Hunter and Kleckner, 2001). The locus and assay are shown schematically in Figure 4A, B.

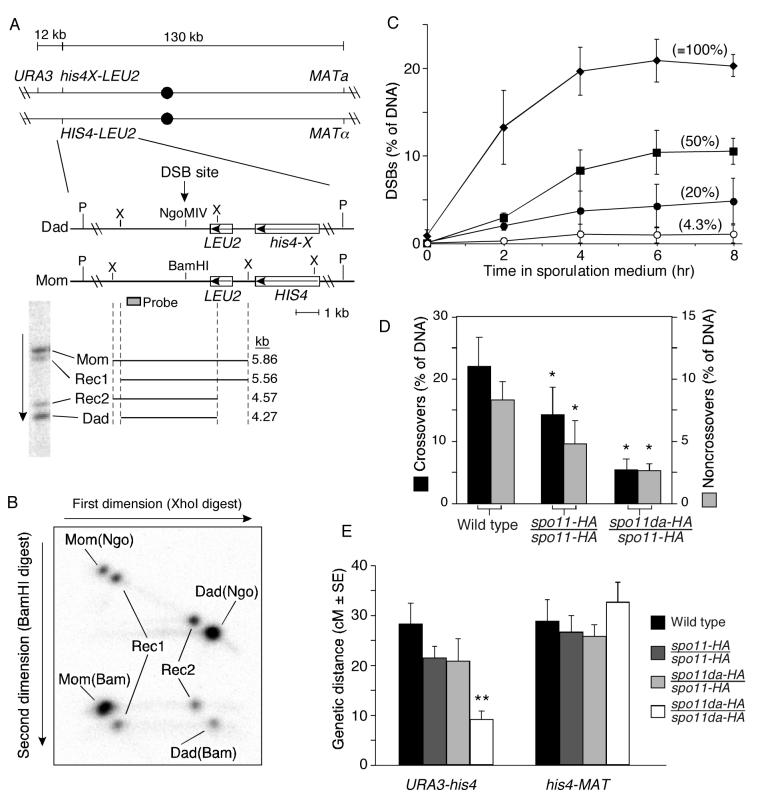

Figure 4.

Little or no crossover homeostasis at the HIS4LEU2 DSB hotspot

(A) Maps of the HIS4LEU2 alleles (middle) and flanking markers (top). Restriction sites: X, XhoI; P, PstI. A Southern blot of XhoI-digested genomic DNA from a meiotic culture shows migration of parental length fragments and reciprocal crossover recombinants (Rec1, Rec2).

(B) Two-dimensional gel assay for crossover and noncrossover recombination products. XhoI-digested DNA was separated in the first dimension, then digested in the gel with BamHI and electrophoresed in the second dimension. Southern blotting and indirect end labeling revealed 8 spots—two parental species (Mom(Bam) and Dad(Ngo)), two noncrossover gene conversion species (Mom(Ngo) and Dad(Bam)), and four crossover species (Rec1 and Rec2).

(C) Effects of the SPO11 allelic series on DSBs at HIS4LEU2. Genomic DNA was prepared at the indicated times from rad50S strains and breaks were measured at the major DSB site in the HIS4LEU2 locus. Data points are the means ± s.d. of three independent cultures for each strain. Values in parentheses are relative DSB frequencies (percent of wild-type at 6 hr). Diamonds, SPO11/SPO11; squares, spo11-HA/spo11-HA; closed circles, spo11da-HA/spo11-HA; open circles, spo11da-HA/spo11da-HA.

(D) Reduced Spo11 activity causes parallel reductions in both crossover and noncrossover products at HIS4LEU2. Values are means ± s.d. of ≥4 independent cultures. Crossovers and noncrossovers are plotted on different scales to provide visual correction for the two-fold overrepresentation of crossover products (see text). Asterisks indicate values significantly lower than wild type (p<0.025, one-tailed t-test).

(E) Crossover homeostasis in an interval flanking the HIS4LEU2 hotspot. Genetic distances (cM ± standard error) were measured in 150–523 four-spore-viable tetrads from the indicated strains. The double asterisk indicates the only value significantly different from wild type and other mutants (p<0.017, G test).

Two HIS4LEU2 alleles differ by a single base change in the DSB site such that one allele (“Mom”) contains a BamHI site and the other (“Dad”) contains an NgoMIV site. Because of the central placement of the restriction sites, essentially every DSB at this locus results in incorporation of the mismatch into heteroduplex DNA, and thus this marker undergoes gene conversion very frequently. Flanking XhoI restriction polymorphisms allow crossover products to be resolved from parental-length fragments by one-dimensional gel electrophoresis of XhoI-digested genomic DNA, detected by Southern blotting and indirect end-labeling (Figure 4A) (Hunter and Kleckner, 2001). To detect noncrossover products, XhoI-digested DNA was separated in the first dimension, then DNA was digested with BamHI in the gel slice prior to electrophoresis in the second dimension (Figure 4B). On Mom, conversion from BamHI to NgoMIV without crossing over yields a spot that migrates as parental length in the first dimension but is resistant to cleavage with BamHI. On Dad, conversions without crossing are also parental length in the first dimension but are cut by BamHI (Figure 4B).

We determined the effect of spo11 mutations on DSB formation at this locus in strains that differed only in their SPO11 genotype and that carried the rad50S mutation, which causes DSBs to accumulate (Figure 4C). In SPO11+, 20.9 ± 2.4% of the DNA had a DSB (mean ± s.d. for 3 cultures, t=6 hr). DSBs were reduced in the spo11 mutants: 10.4 ± 2.5% in spo11-HA (50% of wild type) and 0.9 ± 0.4% in the spo11da-HA homozygote (4.3% of wild type). Similar to ARG4, the reduction in spo11da-HA was ∼five-fold greater for HIS4LEU2 than for most other regions assayed (compare with Table 1). Because the defect was so severe, recombinant products were not detected over background (data not shown), and the heterozygote spo11-daHA/spo11-HA was used instead (DSB frequency of 4.2 ± 2.5%; 20% of wild type).

We applied the two-dimensional gel assay to RAD50+ strains carrying the SPO11 allelic series (Figure 4D). In SPO11+, 22.0 ± 4.7% of the DNA had a crossover configuration and 8.3 ± 1.5% had undergone a noncrossover gene conversion (mean ± s.d. for 4 cultures), for a crossover/noncrossover ratio of 1.3 ± 0.2. (This ratio is obtained by dividing one-half the crossover frequency by the noncrossover frequency, which corrects for the fact that each crossover event yields two recombinant DNA molecules while each noncrossover event yields just one.) Surprisingly, as Spo11 activity was reduced, both crossovers and noncrossovers dropped in parallel (Figure 4D). The crossover/noncrossover ratios were 1.6 ± 0.4 (spo11-HA/spo11-HA, n=5 cultures) and 1.1 ± 0.3 (spo11da-HA/spo11-HA, n=4). The differences between the ratios are not statistically significant (p≥0.1, two-tailed t-test). These results suggest that the HIS4LEU2 hotspot shows little or no crossover homeostasis.

The physical recombination assay provides several internal consistency checks. For example, amounts of Mom and Dad parental length species should equal one another, amounts of the two reciprocal crossover products should equal one another, and 50% of the DNA should be BamHI-sensitive. These criteria were routinely met (data not shown). More importantly, frequencies of recombinant products agreed well with DSB frequencies, indicating that essentially every DSB results in a detectable recombination event. Correcting for the two-fold overrepresentation of crossover molecules, recombinants were 19.3 ± 3.5%, 11.9 ± 4.4%, and 5.3 ± 1.2% of total DNA for the three SPO11 genotypes, indistinguishable from the rad50S DSB frequencies (see above and Figure 4C; p>0.45, two-tailed t-test). Thus, the lack of crossover homeostasis at HIS4LEU2 is not an artificial consequence of a substantial number of ‘invisible’ recombination events whose frequency varies with SPO11 genotype.

To rule out the possibility that the lack of crossover homeostasis was due to differences in strains relative to the experiments described above, recombination was also assessed using markers flanking the hotspot and an adjacent interval (Figure 4A). Tetrads were dissected from the same strains used for physical analysis as well as the spo11da-HA homozygote, and genetic distances were measured (Figure 4E). In the interval adjacent to the hotspot (his4–MAT), genetic distances were not significantly affected by the spo11 mutations (p≥0.18, G test). Thus, these strains are competent for crossover homeostasis. In the same tetrads, genetic distances in the interval encompassing the hotspot (URA3–his4) were decreased in spo11-HA/spo11-HA and spo11da-HA/spo11-HA to ∼75% of wild type, but these decreases were not statistically significant (p≥0.1, G test). In contrast, crossing over in the spo11da-HA homozygote was significantly reduced (32% of wild type; p<<0.001, G test) (Figure 4E). The differences between the two intervals support the conclusion that HIS4LEU2 is less capable than other regions of displaying crossover homeostasis. However, the spo11 mutants had less effect on crossing over between URA3 and his4 than on crossovers localized specifically at the strong DSB site. Thus, the data also reveal that the larger region encompassing the hotspot can compensate for reduced DSBs to some degree, even if the DSB hotspot itself does not. The genetically assayed interval is larger than the region assayed physically and includes additional DSB sites. The compensation detected genetically is likely due in part to crossover homeostasis at these other DSB sites. We conclude that there is little or no crossover homeostasis at the strong DSB site in the HIS4LEU2 hotspot. Possible reasons for the unusual behavior of this locus are discussed below.

Discussion

Reducing the number of DSBs, and thus total recombination events, does not cause a parallel reduction in the number of crossovers. Instead, there is a tendency for crossovers to be maintained at the expense of noncrossovers. This buffering mechanism, crossover homeostasis, is a new manifestation of crossover control and was, to our knowledge, not previously anticipated. The findings suggest that the decision at the heart of crossover control involves crossover-designation of an appropriate number and distribution of recombination precursors from a larger pool, accompanied by repair of all other precursors through a largely noncrossover pathway(s).

Our findings cannot be explained solely as an artifact of selection bias caused by a requirement for viable progeny. First, crossover homeostasis was seen with a spo11-HA mutation, which does not affect viability. Second, analysis at ARG4 is less sensitive to this concern because four-spore-viable tetrads are not required. Third, this idea can not explain the pattern near HIS4LEU2, where the same tetrads revealed strong homeostasis in one interval but not in another. Fourth, our findings agree with a prior study showing that numbers of Zip3 complexes did not decline in parallel with decreased Spo11 activity (Henderson and Keeney, 2004). Zip3 complexes mark crossover-designated sites (Fung et al., 2004), and cytological analysis of their formation is viability-independent.

Crossover homeostasis and the obligate crossover

In most organisms, nonexchange chromosomes are exceedingly rare (Jones, 1984), for example occurring at <1% in C. elegans oocytes, which have an average of only one crossover per chromosome per meiosis (Dernburg et al., 1998; Hillers and Villeneuve, 2003). The ‘rule’ that nearly every bivalent acquires at least one crossover is referred to as the obligate crossover, but the factors that contribute to its formation are not yet well established. Obviously, at least one DSB must form per bivalent, but after this condition is met, additional factors come into play. For example, the proper recombination partner must be engaged, involving homologous pairing and a bias toward use of the homolog rather than a sister chromatid. Moreover, the differentiation of individual recombination events into crossovers vs. noncrossovers must also be appropriately controlled. Crossover homeostasis reflects a push toward crossover formation at the expense of noncrossovers, suggesting that a primary function of this process is to contribute to formation of the obligate crossover. This idea in turn suggests that the obligate crossover is a genetically programmed event.

If crossover homeostasis were completely efficient, then a single DSB would be enough to assure a crossover. This appears not to be the case in yeast, at least not at ARG4, where there was an apparent maximum chance for a DSB to give a crossover of ∼60%. There are several possible reasons why crossover homeostasis did not drive to 100% crossover designation. For example, the system may be inherently limited in its ability to form a crossover. This could be because the molecular mechanism of the crossover-noncrossover decision is itself limited in enforcing crossover formation, or because there is more than one type of DSB, such that some DSBs are formed on a pairing-only pathway and are incapable of giving rise to crossovers. Alternatively, indirect effects of reduced DSBs might antagonize the normal functioning of crossover control. For example, low DSB levels are accompanied by defects in synaptonemal complex (SC) formation, perhaps because of homologous pairing defects (Henderson and Keeney, 2004). SC components are required for crossover maturation (Borner et al., 2004), so SC defects might lead indirectly to defects in generating products from crossover-designated intermediates.

Other examples of crossover homeostasis

Although crossover homeostasis per se has not been previously described, our observations mesh well with prior studies, in particular elegant experiments with chromosome fusions in C. elegans (Hillers and Villeneuve, 2003). Chromosomes in this organism have map lengths of 50 cM because each chromosome pair undergoes one crossover in each meiosis (Villeneuve, 1994). However, when two 50 cM-long chromosomes were fused, the fusion was not 100 cM, but instead was close to 50 cM (Hillers and Villeneuve, 2003). It is formally possible that the crossover/noncrossover ratio was unchanged but that the fusion chromosomes underwent half as many DSBs per Mb of DNA. However, a more likely explanation is that the same number of DSBs were formed but that crossover control generated a single crossover plus more noncrossovers than usual. This would be an example of crossover homeostasis in reverse of the observations described here.

Crossover homeostasis may also contribute to the observation that bisected (i.e., shortened) chromosomes in budding yeast have increased crossover densities (Kaback et al., 1992; but see also Turney et al., 2004). This interpretation predicts that the crossover/noncrossover ratio increases on bisected chromosomes instead of, or in addition to, an increase in DSB frequency. By the same reasoning, crossover homeostasis may explain cases where a crossover always forms within a region that represents only a tiny fraction of the genome, such as on micro-chromosomes in birds (Rahn and Solari, 1986), or in the pseudoautosomal region of the XY pair in mammals (Burgoyne, 1982). Finally, we note that crossover homeostasis is not expected to occur in organisms that do not show interference, such as S. pombe (Munz, 1994).

Regional and locus-specific differences in crossover homeostasis

There appeared to be differences in crossover homeostasis between intervals (Figure 1C). The molecular basis of this variability remains to be determined. Crossover homeostasis appeared weakest on the smaller two chromosomes (III and VIII) and in centromere-proximal regions, but more intervals on more chromosomes will need to be analyzed to determine if these are general patterns. Note, however, that small chromosomes are more likely to receive zero DSBs, which would essentially dilute out the effects of crossover homeostasis between chromosomes that did receive DSBs.

HIS4LEU2 provides a dramatic case of regional variability, with little or no crossover homeostasis at the strong DSB site despite clear evidence of crossover homeostasis in surrounding areas. Why is HIS4LEU2 unique? It is possible that this locus does not respond to normal controls, but another possibility is that this site is particularly likely to be crossover-designated such that it influences recombination nearby rather than being influenced itself. This interpretation is supported by the observation that the crossover fraction at this locus in SPO11+ was comparable to the maximum attained at ARG4 when DSBs were greatly reduced.

What is the mechanism of crossover homeostasis?

We propose that crossover homeostasis is another face of the same molecular mechanism that gives rise to crossover interference and other manifestations of crossover control. If so, the question of how homeostasis works becomes a question of how crossover control works, and our results provide a test of existing models.

Kleckner and colleagues have proposed a model for crossover interference in which mechanical stress is generated by expansion of chromatin against constraining elements (Borner et al., 2004; Kleckner et al., 2004). Stress promotes structural and enzymatic processes that are necessary for crossover formation, and these processes are accompanied by a local relief of stress. Since stress is needed for crossover designation, propagation of stress relief along the chromosome inhibits crossover formation nearby. One reason this model is attractive is that it provides a single mechanism that integrates crossover interference with a tendency toward an obligate crossover. Interference is enforced by the inhibitory “signal” of stress relief; formation of at least one crossover is ensured by sufficient stress or by sufficient sensitivity to stress (i.e., ability of the recombination machinery to respond appropriately) (see Borner et al., 2004; Kleckner et al., 2004 for more detailed discussion). Importantly, the model also predicts the phenomenon of crossover homeostasis. Our findings are thus consistent with this mechanism for crossover control.

In contrast, our findings offer strong evidence against a “counting” model (Copenhaver et al., 2002; Foss et al., 1993; Stahl et al., 2004), which provides a mechanistic interpretation consistent with an example of a chi-square mathematical model for crossover interference (e.g., McPeek and Speed, 1995). The counting model posits that adjacent crossovers are separated by a fixed number of noncrossovers (with or without an additional small number of non-interfering crossovers). We show here that the crossover/noncrossover ratio varies as Spo11 activity varies. Thus, a “counting number” (i.e., the number of noncrossovers between adjacent crossovers) cannot be a genetically fixed parameter. Moreover, the counting model predicts that interference should extend further as DSBs decrease, because longer physical distances would be needed to satisfy the counting number. We found no evidence for such an increase.

It has also been proposed that one group of DSBs always gives rise to randomly distributed events (noncrossovers plus a few non-interfering crossovers) while a second (perhaps later) round of nonrandomly distributed DSBs gives rise only to interfering crossovers (Stahl et al., 2004). Although we can not exclude this hypothesis, it would require that our spo11 mutations affect only the non-interfering class of DSBs, not the later interfering ones. This possibility seems unlikely because the mutants have biochemically distinct defects: the epitope tag is speculated to interfere with protein-protein interactions; heterozygosity for the DSB-null spo11yf-HA mutation yields a mixed population of active and inactive Spo11 dimers; and homozygosity for spo11da-HA yields a uniform population of catalytically crippled proteins (Diaz et al., 2002).

An important challenge is now to define the genetic underpinnings of crossover homeostasis, especially its suggested relationship to crossover interference. Notably, the crossover homeostasis assay at ARG4 is easier than classical interference measurements by tetrad dissection, which should facilitate further analysis.

Experimental Procedures

Yeast strains, DSB measurements, and return-to-growth analysis

Strains were of the SK1 background (Supplemental Table 8). Markers (described in Supplemental Table 8 legend) were introduced by transformation or crossing and were verified by Southern blot and/or sequencing. Dissection of the SPO11+ cross (N. Hunter, A. Jambhekar, J.P. Lao, S.D. Oh, N. Kleckner and V.B. Boerner, ms. in preparation) was conducted separately from the others. Cultures of rad50S strains were grown in liquid YPA (1% yeast extract, 2% Bacto Peptone, 1% potassium acetate) 13.5 hr, 30°C, harvested, resuspended in 2% potassium acetate and incubated at 30°C or 32°C as indicated. Samples were collected at appropriate times (usually 6 hr), and DNA was prepared for conventional agarose electrophoresis as described (Cao et al., 1990). The HIS4LEU2 probe was as described (probe 291, Cao et al., 1990). High molecular weight DNA was prepared and separated by PFGE as described (Borde et al., 2000). Probes were: chromosome III, CHA1 probe (Borde et al., 2000); chromosome VII (DNA digested with SfiI prior to PFGE), SKI8 coding sequence; chromosome VIII, portion of YHL42w coding sequence (coordinates 15671-16112). Blots were quantified by phosphorimager. DSBs are expressed as percent of total radioactivity in the lane after background subtraction, not including material in the wells. Return-to-growth assays were as described (Diaz et al., 2002).

Tetrad analysis of recombination on chromosomes III, VII, and VIII

Haploids were mated overnight on YPD supplemented with adenine, uracil, lysine, methionine and threonine, then replica-printed to 2% potassium acetate, 0.02% raffinose, 2% agar and incubated 32°C, 48–72 hr. Asci were digested with zymolyase and dissected on YPD plates containing supplements as above. Map distances were calculated from four-spore-viable tetrads using the formula of Perkins (1947). Nonparental ditype ratios (observed/expected) were calculated according to the formula of Papazian (1952). Standard error calculations were performed using the Stahl Lab Online Tools (http://groik.com/stahl/). Tetrads with nonmendelian segregation for either marker of an interval were omitted for calculations for that interval. Tetrads with nonmendelian segregation of ≥3 markers were assumed to be false tetrads (Shinohara et al., 2003) and were omitted (8–23 tetrads per cross). Log-likelihood tests for heterogeneity in segregation patterns (G tests) were as described (Hoffmann et al., 2003). To correct for multiple comparisons, p<0.017 was considered significant (Hoffmann et al., 2003).

Random spore analysis

Freshly made diploids were grown in liquid YPA 13.5 hr, 30°C, harvested, resuspended in 2% potassium acetate and shaken at 30°C. Samples were taken at 8 hr for return-to-growth analysis, and the remainder was sporulated 48–72 hr. Cells were harvested, digested with zymolyase, diluted in 0.1% Tween-20, and sonicated. Appropriate dilutions were plated on synthetic complete medium (SC) lacking arginine. Arg+ spore clones were picked onto SC-Arg, then replica-printed to SC-Ura and SC-Thr. SC-Arg and SC-Ura plates were supplemented with extra threonine (0.2 g/l). Fisher exact test was performed at http://home.clara.net/sisa/. The configuration of NdeI sites flanking ARG4 was determined by restriction digest of PCR-amplified DNA from selected Arg+ clones.

Two-dimensional gel analysis of recombination at HIS4LEU2

Freshly mated diploids were grown 13.5 hr in YPA at 30°C, then cultured in 2% potassium acetate, 0.02% raffinose at 32°C. Forty-ml samples were harvested at 7 hr and 0.4 ml 10% NaN3 was added. DNA was prepared as described (Cao et al., 1990), digested with XhoI, then 2.5 μg was electrophoresed at room temperature for 32 hr at 1.7 V/cm on 0.6% agarose in 1× TBE. A ∼4 cm gel slice containing the region of interest was excised and washed twice in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.9 then once in BamHI digestion buffer. Liquid was replaced with fresh digestion buffer containing 0.1 mg/ml BSA, then 5,000 units BamHI was added and incubated overnight at 37°C. The gel slice was cast in a second 0.6% agarose gel in 1× TBE, then electrophoresed perpendicular to the first dimension 1.7 V/cm, 24 hr, room temperature. DNA was detected with “Probe A” (Hunter and Kleckner, 2001).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We extend special thanks to Stéphane Marcand for support to E.M. that made completion of this work possible. We are grateful to Gareth Jones, Nancy Kleckner, Frank Stahl, Anne Villeneuve, and members of the Keeney lab for stimulating discussions. We thank A. Jambhekar, C. Townsend, and C. Arora for help with strain construction and tetrad dissection. S.K. extends thanks to Frank Graves for support and encouragement. This work was supported by NIH grant R01 GM58673 (to S.K.). N.H. is supported in part by R01 GM74223. E.M. is supported in part by an “aide au retour” fellowship from the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale, France. S.K. is a Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Scholar.

References

- Allers T, Lichten M. Differential timing and control of noncrossover and crossover recombination during meiosis. Cell. 2001;106:47–57. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00416-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop DK, Zickler D. Early decision; meiotic crossover interference prior to stable strand exchange and synapsis. Cell. 2004;117:9–15. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00297-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borde V, Goldman ASH, Lichten M. Direct coupling between meiotic DNA replication and recombination initiation. Science. 2000;290:806–809. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5492.806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borner GV, Kleckner N, Hunter N. Crossover/noncrossover differentiation, synaptonemal complex formation, and regulatory surveillance at the leptotene/zygotene transition of meiosis. Cell. 2004;117:29–45. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00292-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broman KW, Weber JL. Characterization of human crossover interference. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2000;66:1911–1926. doi: 10.1086/302923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgoyne PS. Genetic homology and crossing over in the X and Y chromosomes of mammals. Hum Genet. 1982;61:85–90. doi: 10.1007/BF00274192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao L, Alani E, Kleckner N. A pathway for generation and processing of double-strand breaks during meiotic recombination in S. cerevisiae. Cell. 1990;61:1089–1101. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90072-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copenhaver GP, Housworth EA, Stahl FW. Crossover interference in Arabidopsis. Genetics. 2002;160:1631–1639. doi: 10.1093/genetics/160.4.1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de los Santos T, Hunter N, Lee C, Larkin B, Loidl J, Hollingsworth NM. The Mus81/Mms4 endonuclease acts independently of double-Holliday junction resolution to promote a distinct subset of crossovers during meiosis in budding yeast. Genetics. 2003;164:81–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/164.1.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dernburg AF, McDonald K, Moulder G, Barstead R, Dresser M, Villeneuve AM. Meiotic recombination in C. elegans initiates by a conserved mechanism and is dispensable for homologous chromosome synapsis. Cell. 1998;94:387–398. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81481-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz RL, Alcid AD, Berger JM, Keeney S. Identification of residues in yeast Spo11p critical for meiotic DNA double-strand break formation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:1106–1115. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.4.1106-1115.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foss E, Lande R, Stahl FW, Steinberg CM. Chiasma interference as a function of genetic distance. Genetics. 1993;133:681–691. doi: 10.1093/genetics/133.3.681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung JC, Rockmill B, Odell M, Roeder GS. Imposition of crossover interference through the nonrandom distribution of synapsis initiation complexes. Cell. 2004;116:795–802. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00249-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson KA, Keeney S. Tying synaptonemal complex initiation to the formation and programmed repair of DNA double-strand breaks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:4519–4524. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400843101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillers KJ. Crossover interference. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:R1036–1037. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillers KJ, Villeneuve AM. Chromosome-wide control of meiotic crossing over in C. elegans. Curr. Biol. 2003;13:1641–1647. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann ER, Shcherbakova PV, Kunkel TA, Borts RH. MLH1 mutations differentially affect meiotic functions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2003;163:515–526. doi: 10.1093/genetics/163.2.515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter N, Kleckner N. The single-end invasion: an asymmetric intermediate at the double- strand break to double-holliday junction transition of meiotic recombination. Cell. 2001;106:59–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00430-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones GH. The control of chiasma distribution. Symp. Soc. Exp. Biol. 1984;38:293–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaback DB, Guacci V, Barber D, Mahon JW. Chromosome size-dependent control of meiotic recombination. Science. 1992;256:228–232. doi: 10.1126/science.1566070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeney S. Mechanism and control of meiotic recombination initiation. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2001;52:1–53. doi: 10.1016/s0070-2153(01)52008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleckner N, Zickler D, Jones GH, Dekker J, Padmore R, Henle J, Hutchinson J. A mechanical basis for chromosome function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:12592–12597. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402724101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malkova A, Swanson J, German M, McCusker JH, Housworth EA, Stahl FW, Haber JE. Gene conversion and crossing over along the 405-kb left arm of Saccharomyces cerevisiae chromosome VII. Genetics. 2004;168:49–63. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.027961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPeek MS, Speed TP. Modeling interference in genetic recombination. Genetics. 1995;139:1031–1044. doi: 10.1093/genetics/139.2.1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moens PB, Kolas NK, Tarsounas M, Marcon E, Cohen PE, Spyropoulos B. The time course and chromosomal localization of recombination-related proteins at meiosis in the mouse are compatible with models that can resolve the early DNA-DNA interactions without reciprocal recombination. J. Cell Sci. 2002;115:1611–1622. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.8.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller HJ. The mechanism of crossing over. Am. Nat. 1916;50:193–221. [Google Scholar]

- Munz P. An analysis of interference in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genetics. 1994;137:701–707. doi: 10.1093/genetics/137.3.701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolas A, Treco D, Schultes NP, Szostak JW. An initiation site for meiotic gene conversion in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature. 1989;338:35–39. doi: 10.1038/338035a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page SL, Hawley RS. Chromosome choreography: the meiotic ballet. Science. 2003;301:785–789. doi: 10.1126/science.1086605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papazian HP. The analysis of tetrad data. Genetics. 1952;37:175–188. doi: 10.1093/genetics/37.2.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins DD. Biochemical mutants in the smut fungus Ustilago maydis. Genetics. 1947;34:607–626. doi: 10.1093/genetics/34.5.607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahn MI, Solari AJ. Recombination nodules in the oocytes of the chicken, Gallus domesticus. Cytogenet. Cell Genet. 1986;43:187–193. doi: 10.1159/000132319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara M, Sakai K, Shinohara A, Bishop DK. Crossover interference in Saccharomyces cerevisiae requires a TID1/RDH54- and DMC1-dependent pathway. Genetics. 2003;163:1273–1286. doi: 10.1093/genetics/163.4.1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl FW, Foss HM, Young LS, Borts RH, Abdullah MF, Copenhaver GP. Does crossover interference count in Saccharomyces cerevisiae? Genetics. 2004;168:35–48. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.027789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturtevant AH. The behavior of chromosomes as studied through linkage. Z. Abstam. Vererbung. 1915;13:234–287. [Google Scholar]

- Turney D, de Los Santos T, Hollingsworth NM. Does chromosome size affect map distance and genetic interference in budding yeast? Genetics. 2004;168:2421–2424. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.033555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villeneuve AM. A cis-acting locus that promotes crossing over between X chromosomes in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1994;136:887–902. doi: 10.1093/genetics/136.3.887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.