Abstract

During a molecular phylogenetic survey of extremely acidic (pH < 1), metal-rich acid mine drainage habitats in the Richmond Mine at Iron Mountain, Calif., we detected 16S rRNA gene sequences of a novel bacterial group belonging to the order Rickettsiales in the Alphaproteobacteria. The closest known relatives of this group (92% 16S rRNA gene sequence identity) are endosymbionts of the protist Acanthamoeba. Oligonucleotide 16S rRNA probes were designed and used to observe members of this group within acidophilic protists. To improve visualization of eukaryotic populations in the acid mine drainage samples, broad-specificity probes for eukaryotes were redesigned and combined to highlight this component of the acid mine drainage community. Approximately 4% of protists in the acid mine drainage samples contained endosymbionts. Measurements of internal pH of the protists showed that their cytosol is close to neutral, indicating that the endosymbionts may be neutrophilic. The endosymbionts had a conserved 273-nucleotide intervening sequence (IVS) in variable region V1 of their 16S rRNA genes. The IVS does not match any sequence in current databases, but the predicted secondary structure forms well-defined stem loops. IVSs are uncommon in rRNA genes and appear to be confined to bacteria living in close association with eukaryotes. Based on the phylogenetic novelty of the endosymbiont sequences and initial culture-independent characterization, we propose the name “Candidatus Captivus acidiprotistae.” To our knowledge, this is the first report of an endosymbiotic relationship in an extremely acidic habitat.

Until recently, the majority of microbial studies of acid mine drainage habitats relied upon cultivation-based approaches. A few studies have used 16S rRNA gene-based molecular methods and have increased the number of bacterial and archaeal lineages recognized to be associated with acid mine drainage systems (12, 15, 17). However, the total number of lineages remains small (<15), especially compared to other ecosystems (7, 12). Even fewer studies have focused on eukaryotes associated with acid mine drainage communities (4, 16, 30, 36). Recently, Amaral Zettler et al. (4) reported notable diversity among eukaryotes in the acid mine drainage-impacted Rio Tinto River in Spain. Ciliates belonging to the genus Cinetochilium, an amoeba related to the genus Vahlkampfia, and three flagellates (Eutreptia spp.) were isolated from an acid mine drainage site and shown to be able to graze on mineral-oxidizing acidophilic bacteria (30).

The Richmond Mine at Iron Mountain, Calif., is an ideal site for acid mine drainage studies because it is possible, via mining tunnels, to access biofilms that are directly associated with pyrite (FeS2) dissolution (7). This subsurface habitat houses a chemolithotroph-based microbial community sustained ultimately by dissolution of pyrite within the Richmond ore body. Subaqeous and subaerial pyrite-attached biofilms associated with the acid mine drainage are typically between pH 0.7 and 0.9 and 35 to 50°C (G. K. Druschel, B. J. Baker, T. Gihring, and J. F. Banfield, submitted for publication). We used culture-independent approaches to detect a novel group of protist endosymbionts present in acid mine drainage at Iron Mountain. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a protist-bacterial symbiotic relationship in an acid mine drainage community.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Site descriptions.

Environmental samples from the Richmond Mine, Iron Mountain, Calif., were aseptically collected on 19 January 2001 and 12 March 2002. A general description of the Richmond mine site is provided elsewhere (17). The sites sampled in this study (A drift slime streamers and A, B, and C drift weirs) were described by Bond et al. (12). One site previously not sampled, Back A drift, referred to as the red pool, was located peripherally to the primary drainage flow. This site was oxidized and higher in pH (1.4 versus <1) than the primary drainage (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Physical and chemical measurements of Richmond Mine samples in this study

| Site | Temp (°C) | pH | Concn (mM)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe2+ | Fe3+ | SO42− | |||

| A drift weir | 30 | 0.9 | 81 | 177 | 560 |

| Back A drift | 30 | 1.4 | 10 | 25 | 142 |

| B drift weir | 27 | 0.8 | 55 | 257 | 929 |

| C drift weir | 32 | 0.9 | 47 | 195 | 635 |

| Five way | 29 | 0.8 | 64 | 165 | 657 |

Geochemical analyses.

Temperature, pH, and conductivity were measured directly in the mine with electrodes, as described elsewhere (16). Samples were collected in sterile 60-ml plastic syringes, filtered through an Acrodisc (0.45- to 0.2-μm syringe filter), and stored on ice in sterile 15-ml Falcon tubes for transport back to the laboratory. Geochemical analyses were performed as described previously (16). Sulfate was analyzed by ion chromatography. Ferric and total iron were measured immediately after collection by the ferrozine and 1,10-phenanthroline methods (HACH DR/2010 spectrophotometer methods 8147 and 8146).

16S rRNA gene cloning and sequencing.

Samples stored frozen in 25% glycerol were washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline buffer (at pH 1.2 to prevent lysis of obligate acidophiles) to remove extracellular ions. DNA was extracted from 3-ml aliquots of the samples with a modified phenol-chloroform extraction method previously described by Bond et al. (12).

Bacterial 16S rRNA gene sequences were amplified with broad-specificity primers for the bacterial domain (27F, 5′-GTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′, and 1492R, 5′-GGWDACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′; W represents A or T). With the ProofSprinter PCR kit, PCR mixtures were prepared as follows; 1 unit of Taq/Pwo, 0.1% Tween, 3 ng of each primer/μl, 2% dimethyl sulfoxide, 250 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphate mix, and approximately 1 to 5 ng of template DNA with double-distilled water added to make 25-μl total reactions. PCRs were optimized on a Hybaid PCRexpress thermal gradient thermal cycler with annealing temperatures ranging from 47 to 62°C, with an initial 2 min at 94°C followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, annealing temperature of 30 s, and 1.5 min at 72°C.

The PCR product from the single brightest band was gel purified and cloned with the Promega pGEM-T cloning kit. Restriction fragment length polymorphism patterns of 16S rRNA genes amplified directly from white colonies were generated with MspI and AluI restriction enzymes, and representatives were selected for sequencing. Plasmids were isolated from these representative clones with the QIAprep Spin miniprep kit (Qiagen Inc.), and the 16S rRNA gene insert sequences were amplified with the promoter site (T7 and SP6) primers. Nearly complete sequences were obtained with combinations of broadly conserved primers, including 533F (5′-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3′, where M stands for A or C), as previously described (12).

Sequence analyses.

16S rRNA gene sequences were compared to sequences available in the public databases. Four novel alphaproteobacterial sequences from this study and closely related rRNA gene sequences were imported into the ARB software package (http://www.arb-home.de/). Alignments were prepared in ARB with the fast aligner with subsequent manual refinements. A putative intervening sequence (IVS), detected in three of the four clones during the alignment process, was removed prior to phylogenetic inference. Secondary-structure predictions of the IVS were made with DNA mfold analysis, available on Michael Zucker's web site (http://bioinfo.math.rpi.edu/≈zukerm/). A maximum-likelihood tree, presented in Fig. 1, was generated with fastDNAML with a standard Lane mask, available in the ARB package. Statistical support for the inferred topology was determined with Bayesian posterior probabilities and evolutionary distance bootstrapping, as previously described (8).

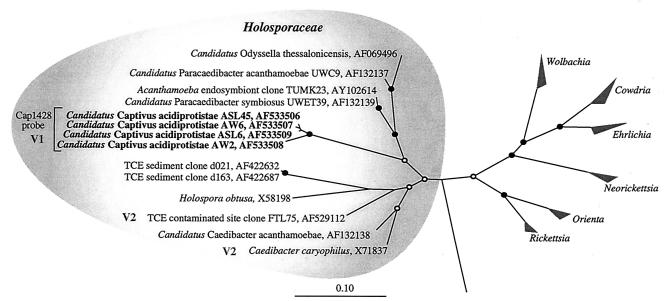

FIG. 1.

Maximum-likelihood tree of the order Rickettsiales. “Candidatus Captivus acidiprotistae” clones are shown in bold. The family Holosporaceae is shaded on the left. Representative genera (grouped) of the Rickettsiaceae and Ehrlichiaceae families are on the right. Sequences that contain IVSs are labeled with the variable region (39) where it is located. The bar represent 0.1 change per site. Nodes supported by posterior probabilities and bootstrap values of 100% are indicated by solid circles, and nodes supported by a lower percentage by one or both analyses are indicated by open circles. Nodes lacking circles were not reproducibly resolved.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis and probe design.

Samples were washed with a low-pH (1.2) phosphate-buffered saline buffer and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde within 12 h of collection. Hybridizations were performed as previously reported with a 46°C incubation and 48°C 15-min wash (12). Hybridizations were also counterstained with DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride) as a measure of the total cell number. Three-dimensional deconvolved images were generated with the DeltaVision image acquiring system (Applied Precision, Inc).

An oligonucleotide probe, Cap1428, was designed to specifically target the 16S rRNAs of the four endosymbiont clones obtained in this study with the probe design function tool in ARB. The optimal stringency for this probe was determined directly on fixed acid mine drainage samples with 5% formamide increments from 20 to 50%. The pure strain with the least number of mismatches to Cap1428, Prosethcobacter fusiformis, had three mismatches, two of which were strong and centrally located, so it was decided not to use a negative control strain for this probe. Three domain-level oligonucleotide probes specific for the Eucarya were modified from existing probes (Table 2), based on previously described design considerations (28), and used in concert (EUKb-mix). One or more of the EUKb-mix probes had exact matches to all eukaryotes with the exception of two basal lineages, Spironucleus and Giardia. The optimal stringencies of the probes (Table 2) were determined empirically with pure cultures of Saccharomyces cerevisiae (positive control) and Escherichia coli (negative control). No-probe controls were used on all samples to confirm that nonspecific autofluorescence was not responsible for the observed staining. Direct counts of protists containing endosymbionts were performed on 20 different fields of view from different sites (red pool, B weir, and five way).

TABLE 2.

Probes developed and used in this study

| Probe (E. coli position) | Probe sequence (5′-3′)d | Length (nt) | Tm (°C)a | GC% | Optimal formamide concn (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cap1428 (1428-1445) | AGGACACCGCCTTAAGGC | 18 | 60 | 61 | 40 | This study |

| EUKb1193 (1193-1209)b | GGGCATMACDGACCTGTT | 18 | 57 | 55 | 20-35 | 48 |

| EUKb503 (503-519)b,c | GGCACCAGACTKGYCCTC | 18 | 61 | 67 | 20-35 | 3 |

| EUKb310 (310-325)b | TCAGGCBCCYTCTCCG | 16 | 61 | 70 | 20-35 | 21 |

Nearest neighbor calculation (http://paris.chem.yale.edu/extinct.html) with 50 mM NaCl and 50 μM oligonucleotide.

Used in concert as EUK-mix.

Requires competitor probe GACACCAGACTKGYCCTC.

M, A or C; K, G or T; Y, C or T; B, G or T or C.

Determination of internal pH of acid mine drainage protists.

To estimate the internal pH of the eukaryotes hosting the endosymbionts, we used the LysoSensor Green DND-189 probe, available from Molecular Probes. Wet mounts of unfixed acid mine drainage samples, stained with the probe, were visualized under a Leica DMRX epifluorescence microscope with a fluorescein isothiocyanate filter.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

Sequences were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers AF533506 through AF533509, and oligonucleotide probe sequences (Table 2) have been deposited at probeBase (35).

RESULTS

Geochemistry.

Physical and chemical parameters for the samples collected in this study are detailed in Table 1. The pH range (0.8 to 1.4) for the samples was typical for the Richmond Mine. However, the in situ temperatures (27 to 32°C) were among the lowest recorded at this site (16) and correlated with low rainfall, probably due to limited flushing from hotter regions within the ore deposit. Iron and sulfate concentrations were consistent with previous observations (12, 17), with the exception of the Back A drift solution, which was characterized by lower concentrations of iron and sulfate. The Back A site is separated from the main drainage flow. Oxidation of ferrous iron has led to precipitation of iron oxyhydroxide minerals, which confer the distinctive red color on this pool.

Phylogenetic identification of acid mine drainage-associated bacterial endosymbionts.

Following the initial analysis of several PCR-clone libraries prepared from Richmond Mine acid drainage samples, we obtained four nearly full-length 16S rRNA gene sequences not belonging to any prokaryotic lineage previously recognized in acid mine drainage (7). These clones were obtained from two independent libraries of the A drift waterfall (clones AW2 and AW6) and slime streamer (clones ASL6 and ASL45) samples and had ≥97% sequence identity to each other.

Comparative analysis of the clone sequences with available 16S rRNA gene data revealed that they were members of the Alphaproteobacteria. More specifically, they belonged to the exclusively endosymbiotic Rickettsiales family Holosporaceae (Fig. 1) and had between 89 and 92% sequence identity with their closest relatives, Acanthamoeba endosymbiont sequences. The inferred topology shown in Fig. 1 was confirmed by generating multiple trees with various inference methods (parsimony, maximum likelihood, and Bayesian inference) and including differing taxonomic groups. Since all of the characterized members of the Holosporaceae have only been cocultivated with their hosts and cannot be characterized in the classic sense, they are provisionally classified as Candidatus species (38) (Fig. 1).

Analyses of 16S rRNA gene intervening sequences.

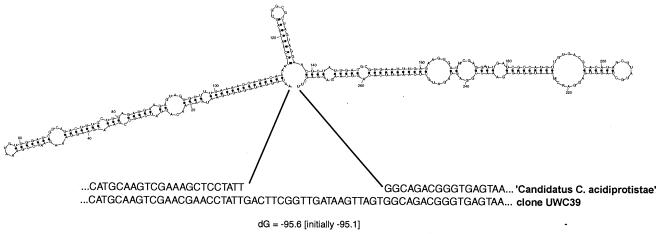

Initial searches of the public databases with the acid mine drainage clone sequences revealed that a large portion at the 5′ end of the genes did not match those of the closest relatives. Further investigation revealed that a putative intervening sequence (IVS), 273 bp in length, was present in three of the clones. The fourth clone (ASL6) was missing the 5′ end sequence up to position 244 (E. coli numbering), likely due to a PCR mispriming. Alignments of the acid mine drainage clone sequences with similar sequences in the database showed that the acid mine drainage clone IVS is located between positions 82 and 103 (E. coli numbering, Fig. 2). This is variable region V1 of the 16S rRNA molecule, as defined by Neefs et al. (39). Similarity searches revealed no homologs of the IVS. The IVS had a well-defined predicted secondary structure suggestive of a functional RNA (Fig. 2). The IVS did not contain an open reading frame and is therefore not an intron.

FIG. 2.

Predicted RNA secondary structure of “Candidatus Captivus acidiprotistae” IVS. An alignment of IVS region with a close relative is shown beneath.

During preparation of alignments for members of the Holosporaceae, we identified a putative 88-bp IVS in the trichloroethylene-contaminated site clone FTL75 (accession number AF529112) located in the V2 region of the gene (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Bacteria containing IVSs or putative IVSs in their rRNA genes and selected properties; all have predicted secondary structurea

| Gene and organism | Family affiliation | Host | Length of IVS (bp) | Location of IVS in rRNA gene (start position) | Fragmented rRNA after IVS excision | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16S | ||||||

| “Candidatus C. acidiprotistae” | Holosporaceae | Protist | 273 | 82 (V1) | NA | This study |

| Caedibacter caryphilus | Holosporaceae | Paramecium | 194 | 187 (V2) | Yes | 50 |

| Clone FTL75 | Holosporaceae | NA | 88 | 200 (V2) | NA | Unpublished data |

| Clostridium paradoxum | Clostridiaceae | Free living | 120-131 | 73 (V1) | Yes | 43 |

| Helicobacter canis | Helicobacteraceae | Dog/cat pathogen | 235 | 199 (V2) | Yes | 33 |

| Campylobacter helveticus | Campylobacteraceae | Mammal enteric | 148 | 210 (V2) | NA | 34 |

| Campylobacter sputorum | Campylobacteraceae | Mammal enteric | 250 | 212 (V2) | Yes | 49 |

| Rhizobium tropici | Rhizobiaceae | Phaseolus vulgaris | 72 | 71 (V1) | NA | 53 |

| 23S | ||||||

| Leptospira spp. | Leptospiraceae | Mammal pathogen | 485-759 | 1200, 1224 (helix 45) | Yes | 44, 45 |

| Helicobacter spp. | Helicobacteraceae | Pathogens | 93-377 | 545 (helix 9) | Yes | 29 |

| Campylobacter spp. | Campylobacteraceae | Mammal enteric | ∼120-180 | (helix 45) | Yes | 51 |

| Brucella meitensis | Brucellaceae | Mammal pathogen | 178 | 130 (helix 9) | Yes | 14 |

| Rhodopseudomonas palustris | Bradyrhizobiaceae | Free living | ∼100 | 125 (helix 9) | Yes | 54 |

| Agrobacterium | Rhizobiaceae | Root nodules | NA | NA | Yes | 27, 46 |

| Rhizobium | Rhizobiaceae | Root nodules | 130 | (helix 9) | Yes | 31, 46 |

| Bradyrhizobium | Bradyrhizobiaceae | Root nodules | ∼110 | 139 (helix 9) | Yes | 46 |

| Coxiella burnetii | Coxiellaceae | Mammal pathogen | 444 | 1176 (helix 45) | NA | 1 |

| Rhodobacter spp. | Rhodobacteraceae | Phototroph | 50-100 | 130 (helix 9) | Yes | 46 |

| Haemophilus influenzae | Pasteurellaceae | Mammal pathogen | 112, 121-123 | 542 and 1176 (helices 25 and 45) | Yes | 49 |

| Yersinia spp. | Enterobacteriaceae | Mammal enteric | ∼100 | 1150 | Yes | 47 |

| Salmonella spp. | Enterobacteriaceae | Pathogen | 90-167 | 550 and 1170 (helices 25 and 45) | Yes | 13, 41, 42 |

| Proteus vulgaris | Enterobacteriaceae | Mammal pathogen | 200 | 533 (helix 25) | Yes | 6 |

| Proteus and Providencia | Enterobacteriaceae | Mammal enteric | 113, 183-187 | (helix 25) | Yes | 37 |

| 113-123 | (helix 45) | Yes | 42 | |||

| Klebsiella oxytoca | Enterobacteriaceae | Mammal enteric | NA | (helix 25) | Yes | 42 |

| Citrobacter amalonaticus | Enterobacteriaceae | Mammal enteric | NA | (helix 25 and 45) | Yes | 42 |

| Providencia stuartii | Enterobacteriaceae | Mammal enteric | NA | (helix 25) | Yes | 42 |

| Providencia rettgeri | Enterobacteriaceae | Mammal enteric | NA | (helix 25 and 45) | NA | 42 |

| Actinobacillus sp. | Pasteurellaceae | Mammal enteric | 112 | 1180 (helix 45) | Yes | 23 |

| “Candidatus Probacter acanthamoebae” | Neisseriaceae | Acanthamoeba sp. | 146 | (helix 25) | NA | 26 |

Microscopic characterization of acid mine drainage endosymbionts and their hosts.

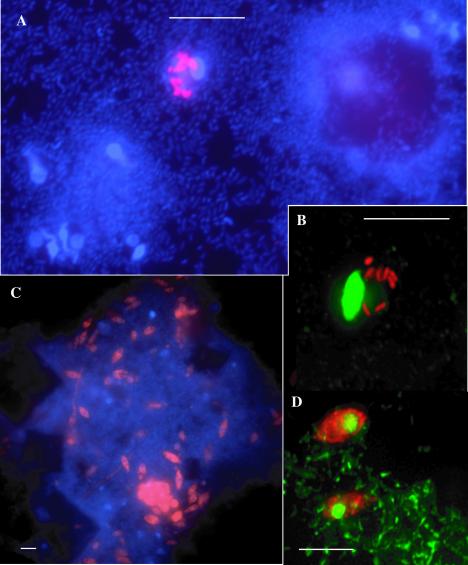

A 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probe, Cap1428, was designed to specifically target the acid mine drainage clone group (Table 2). Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analyses with this probe revealed cells localized within one morphological type of protist, a small ciliate or flagellate, 4 to 7 μm in length, with a single oval nucleus up to 5 μm long located to one side of the cell. The average number of cells per host cell was 6, but the numberranged from 1 to 15 cells. A survey of several different sites within the Richmond Mine showed that the bacterial endosymbiont appeared to be ubiquitous in this environment. In order to determine how widespread these bacteria are within the eukaryotic community, direct counts of protists with eukaryote-specific FISH probes were performed (EUKb-mix, see below). Approximately 4% of counted protists (14 of 386 cells) contained the Holosporaceae endosymbionts.

Simultaneous staining with DAPI and the EUK502 (3) probe showed that this probe does not hybridize to the 18S rRNA of many eukaryotes in the acid mine drainage samples. We modified EUK502 and two other domain-level eukaryote probes to broaden their specificity and normalize their melting temperatures (renamed in accordance to their new positions as EUKb310, EUKb503, and EUKb1193; Table 2) and used them in concert (EUKb-mix). This made it possible to visualize most eukaryotes in the samples (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

FISH analyses of Richmond Mine samples with EUKb-mix and Cap1428 probes. A and B show endosymbionts labeled with the Cap1428 probe in red (indocarbocyanine) adjacent to the protist host nucleus in blue or green (DAPI) of the protist. C and D show the eukaryotic population in an A drift sample labeled with EUKb-mix probes (indocarbocyanine) counterstained with DAPI, highlighting nuclei (blue or green). All scale bars, 5 μm.

The optimal stringency for the four probes was determined by adjusting the formamide concentration. We found that the Cap1428 probe had a strong and specific signal for the endosymbiont cells up to 40% formamide, becoming weaker at 45 and 50% formamide. All three EUKb-probes were specific for eukaryotes from 20 to 35% formamide with no loss of signal intensity. This makes them ideal for simultaneous use with other more specific and differentially labeled probes.

Use of the LysoSensor probe revealed that the eukaryotes, including the endosymbiont hosts, in the acid mine drainage samples had approximately neutral pH cytosol. This is consistent with previous estimates of cytosolic pH in extremely acidophilic eukaryotes (9, 32) and indicates that acid mine drainage eukaryotes maintain a pH gradient of at least five orders of magnitude across their membranes.

DISCUSSION

Culture-independent methods have led to the identification of several obligately intracellular Rickettsiales-like bacteria in neutrophilic protists from clinical and soil environments (2, 11, 25, 20, 50). To our knowledge, this is the first report of endosymbionts in acidophilic protist hosts. These endosymbionts are significantly divergent (>8% at the 16S rRNA gene level) from their closest relatives from circumneutral pH habitats (Fig. 1) and likely represent at least a novel genus (51) for which we propose the name “Candidatus Captivus acidiprotistae” [cap.ti′ vus, L. masc. n. captivus prisoner/captive. a.ci.di.pro.tis′ tae. L. neut. N. acidum the acid, N.L. masc./fem. n. protista protist (monocellular microbe), N.L. gen. masc./fem. n. acidiprotistae of an acid protist, indicating the acidophilic nature of the host]. The preliminary description for this genus and species is as follows: member of the class Alphaproteobacteria, order Rickettsiales, and family Holosporaceae, based on PCR-clone sequences (accession number AF533506-8) and oligonucleotide probe Cap1428 (5′-AGGACACCGCCTTAAGGC-3′); not cultivated on cell-free medium, rod-shaped ≈1.5 to 2 μm in length, ≈0.2 to 0.7 μm in diameter; obligate intracellular bacterium living in an unidentified acidophilic protist host native to acid mine drainage.

Thus far, all characterized members of the Rickettsiales (including mitochondria [19]) are obligate endosymbionts or parasites of eukaryotic hosts. More specifically, characterized members of the family Holosporaceae, to which “Candidatus C. acidiprotistae” belongs, are all obligate endosymbionts of either Acanthameoba or Paramecium (Fig. 1). Therefore, the phylogenetic position of “Candidatus C. acidiprotistae” is consistent with its observed lifestyle. Morphologically, the host appears to be uniform and may be a single protist species. Our intention is to design and apply eukaryote-specific probes to resolve the host identity.

The identification of intracellular bacteria within an exceptionally acidic environment raises many physiological, evolutionary and ecological questions. For example, what is the mechanism by which “Candidatus C. acidiprotistae” is transferred between protists? If the endosymbionts reside directly in the host cytoplasm they probably are neutrophilic and more likely to be vertically inherited between hosts to avoid exposure to the toxic acid mine drainage solutions (pH < 1). If, however, the endosymbionts are surrounded by host-derived membranes, they could be living in low pH vacuoles within the protist. Thus, they may be adapted to acidic environments and horizontal transmission could be a viable mechanism of dispersal, although no free-living cells were observed with the endosymbiont-specific probe. We intend to use electron microscopy to look for evidence of membranes surrounding the endosymbiont to determine the more likely scenario.

The 16S rRNA gene sequences of “Candidatus C. acidiprotistae” contain a putative 273-bp intervening sequence (IVS) (Table 3). The occurrence of IVSs in rRNA genes is uncommon in prokaryotes and appears mainly localized to symbionts and pathogens of eukaryotic hosts (Table 3). There is emerging evidence that IVSs are the result of lateral transfer rather than vertical inheritance. Miller et al. (37) and Pronk and Sanderson (42) both found sporadic distribution of related IVSs in the 23S rRNA genes of pathogenic members of the Enterobacteriaceae indicative of lateral transfer. A similar scattered distribution of IVSs was observed in the present study within the family Holosporaceae (Fig. 1). The GC content of the “Candidatus C. acidiprotistae” IVS (39.3%) is notably lower than the rest of the 16S rRNA gene (51.6%), consistent with a possible lateral transfer. IVSs have also been identified in variable regions of the 18S rRNA genes of endosymbiont hosts including Acanthamoeba castellanii (22) and Phreatamoeba balamuthi (24).

The function of IVSs remains unknown (42), but their formation may be part of the overall process of adapting to a close working relationship with a eukaryotic host, which in bacterial endosymbionts includes genome reduction and lateral gene transfer to hosts (5). Perhaps the IVSs specifically contribute to the likely increased communication that is required between the host and endosymbiont. In support of this hypothesis, IVSs investigated at the RNA level are all excised from the transcribed rRNA (Table 3) and have pronounced secondary structure suggestive of a functional RNA independent of the ribosome, but transcriptionally linked to protein production in the endosymbiont and, in some cases, the host.

At this stage we can only speculate on the nature of the symbiotic relationship between “Candidatus C. acidiprotistae” and its acidophilic protist host. Several possibilities exist. First, there is no benefit to the host, and the bacteria have simply exploited a protist predator for protection within a nutrient-rich niche. A second possibility is that the endosymbiont somehow provides a selective advantage to its host, for example, by producing R bodies that are toxic to other protists lacking the symbionts (10). A third possibility is that the endosymbionts may provide an essential nutrient to the host, such as fixed nitrogen. This is certainly the case for other symbiotic members of the Alphaproteobacteria, such as Rhizobium, that provide fixed nitrogen to their plant hosts. This type of association may be advantageous in a subsurface habitat such as the Richmond Mine, which is limited in fixed nitrogen (7).

The discovery of endosymbiotic bacteria within extremely acidophilic protist hosts suggests an unusually stringent obligate relationship and may provide a useful model for the study of endosymbiosis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Greg Druschel for the geochemical analyses and Gene Tyson and an anonymous reviewer for providing valuable comments on the manuscript. We also acknowledge Hans Trüper for advice on the Candidatus nomenclature.

This work was funded by the NSF Life in Extreme Environments (LExEn) Program, the DOE Microbial Genomics Program, and the NSF Biocomplexity Program.

REFERENCES

- 1.Afseth, G., Y.-Y. Mo, and L. P. Mallavia. 1995. Characterization of the 23S and 5S rRNA genes of Coxiella burnetii and identification of an intervening sequence within the 23S rRNA gene. J. Bacteriol. 177:2946-2949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amann, R., N. Springer, W. Ludwig, H. D. Gortz, and K.-H. Schleifer. 1991. Identification in situ and phylogeny of uncultured bacterial endosymbionts. Nature 351:161-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amann, R. I., B. J. Binder, R. J. Olson, S. W. Chisholm, R. Devereux, and D. A. Stahl. 1990. Combination of 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes with flow cytometry for analyzing mixed microbial populations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:1919-1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amaral Zettler, L. A., F. Gomez, E. Zettler, B. G. Keenan, R. Amiles, and M. L. Sogin. 2001. Microbiology: eukaryotic diversity in Spain's River of Fire. Nature 417:137. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Andersson, G. E., A. Zomorodipour, J. O. Andersson, T. Sicheritz-Pontén, U. C. M. Alsmark, R. M. Podowski, A. K. Näslund, A.-S. Eriksson, H. H. Winkler, and C. G. Kurland. 1998. The genome sequence of Rickettsia prowazekii and the origin of mitochondria. Nature 396:133-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asai, T., D. Zaporojets, C. Squires, and C. L. Squires. 1999. An Escherichia coli strain with all chromosomal rRNA operons inactivated: complete exchange of rRNA gene between bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:1971-1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baker, B. J., and J. F. Banfield. 2003. Microbial communities in acid mine drainage. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 44:139-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baker, B. J., D. P. Moser, B. J. MacGregor, S. Fishbain, M. Wagner, N. Fry, B. Jackson, N. Speolstra, S. Loos, K. Takai, J. Fredrickson, D. Balkwill, T. C. Onstott, C. F. Wimpee, and D. A. Stahl. 2003. Related assemblages of sulfate-reducing bacteria associated with ultradeep gold mines of South Africa and deep basalt aquifers of Washington State. Environ. Microbiol. 5:267-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beardall, J., and L. Entwisle. 1984. Internal pH of the obligate acidophile Cyanidium caldarium Geitler (Rhodophyta?). Phycologia 23:397-399. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beier, C. L., M. Horn, R. Michel, M. Schweikert, H.-D. Goertz, and M. Wagner. The Paramecium tetraurelia endosymbiont Caedibacter taeniospiralis is most closely related to the human pathogen Francisella tularensis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:6043-6050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Birtles, R. J., T. J. Rowbotham, R. Michel, D. G. Pitcher, B. Lascola, S. Alexiou-Daniel, and D. Raoult. 2000. “Candidatus Odysella thessalonicensis ” gen. nov., sp. nov., an obligate intracellular parasite of Acanthamoeba species. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 50:63-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bond, P. L., S. P. Smigra, and J. F. Banfield. 2000. Phylogeny of microorganisms populating a thick, subaerial, predominantly lithotrophic biofilm at an extreme acid mine drainage site. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:3842-3849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burgin, A. B., K. Parodos, D. J. Lane, and N. R. Pace. 1990. The excision of intervening sequences from Salmonella 23S ribosomal RNA. Cell 60:405-414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bricker, B. 2000. Characterization of the three ribosomal RNA operons, rrnA, rrnB, and rrnC, from Brucella melitensis. Gene 255:117-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brofft, J. E., J. V. McArthur, and L. J. Shimkets. 2002. Recovery of novel bacterial diversity from a forested wetland impacted by reject coal. Environ. Microbiol. 4:764-769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edwards, K. J., P. L. Bond, G. K. Druschel, M. M. McGuire, R. J. Hamers, and J. F. Banfield. 2000. Geochemical and biological aspects of sulfide mineral dissolution: lessons from Iron Mountain, California. Chem. Geol. 169:383-397. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edwards, K. J., T. M. Gihring, and J. F. Banfield. 1999. Seasonal variations in microbial populations and environmental conditions in an extreme acid mine drainage environment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:3627-3632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Emelyanov, V. V. 2001. Ricketseaceae, rickettsia-like endosymbionts, and the origin of mitochondria. Biosci. Rep. 21:1-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Evguenieva-Hackenberg, E., and G. Klug. 2000. RNase III processing of intervening sequences found in helix 9 of 23S rRNA in the alpha subclass of proteobacteria. J. Bacteriol. 182:4719-4729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fritsche, T. R., R. K. Gautom, S. Seysdirashti, D. L. Bergeron, and T. D. Lindquist. 1993. Occurrence of bacterial endosymbionts in Acanthamoeba spp. isolated from corneal and environmental specimens and contact lenses. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:1122-1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giovannoni, S. J., E. F. Delong, G. J. Olsen, and N. R. Pace. 1988. Phylogenetic group-specific oligonucleotide probes for identification of single microbial cells. J. Bacteriol. 170:720-726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gunderson, J. H., and M. L. Sogin. 1986. Length variation in eukaryotic rRNAs: small subunit rRNAs from the protists Acanthamoeba castellanii and Euglena gracilis. Gene 44:63-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haraszthy, V. I., G. J. Sunday, L. A. Bobek, T. S. Motley, H. Preus, and J. J. Zambon. 1992. Identification and analysis of the gap region in the 23S ribosomal RNA from Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. J. Dent. Res. 71:1561-1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hinkle, G., D. D. Leipe, T. A. Nerad, and M. L. Sogin. 1994. The unusually long small subunit ribosomal RNA of Phreatamoeba balamuthi. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:465-469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horn, M., T. R. Fritsche, R. K. Gautom, K. H. Schleifer, and M. Wagner. 1999. Novel bacterial endosymbionts of Acanthamoeba spp. related to the Paramecium caudatum symbiont Caedibacter caryphilus. Environ. Microbiol. 1:357-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horn, M., T. R. Fritsche, T. Linner, R. K. Gautom, M. D. Harzenetter, and M. Wagner. 2002. Obligate bacterial endosymbionts of Acanthamoeba spp. related to the β-Proteobacteria: proposal of ‘Candidatus Procabacter acanthamoebae' gen. nov., sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 52:599-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hsu, D., Y. C. Zee, J. Ingraham, and L. M. Shih. 1992. Diversity of cleavage patterns of Salmonella 23S rRNA. J. Gen. Microbiol. 138:199-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hugenholtz, P., G. W. Tyson, and L. L. Blackall. 2001. Design and evaluation of 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes for fluorescence in situ hybridisation. Methods Mol. Biol. 179:29-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hurtado, A., J. P. Clewly, D. Linton, R. J. Owen, and J. Stanley. 1997. Sequence similarities between large subunit ribosomal RNA gene intervening sequences from different Helicobacter species. Gene 194:69-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson, D. B., and L. Rang. 1993. Effects of acidophilic protozoa on populations of metal-oxidizing bacteria during the leaching of pyritic coal. J. Gen. Microbiol. 139:1417-1423. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klein, F., R. Samorski, G. Klug, and E. Evguenieva-Hackenberg. 2002. Atypical processing in domain III of 23S rRNA of Rhizobium leguminosarum ATCC 10004T at a position homologous to an rRNA fragmentation site in protozoa. J. Bacteriol. 184:3176-3185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lane, A. E., and J. E. Burris. 1981. Effects of environmental pH on the internal pH of Chlorella pyrenoidosa, Scenedesmus quadricauda, and Euglena mutabilis. Plant Physiol. 68:439-442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Linton, D., J. P. Clewly, A. Burnens, R. Owen, and J. Stanley. 1994. An intervening sequence (IVS) in the 16S rRNA gene of the eubacterium Helicobacter canis. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:1954-1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Linton, D., F. E. Dewhirst, J. P. Clewley, R. J. Owen, A. P. Burnens, and J. Stanley. 1994. Two types of 16S rRNA gene are found in Campylobacter helveticus: analysis, applications and characterization of the intervening sequence found in some strains. Microbiology 140:847-855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loy, A., M. Horn, M. Wagner. 2003. ProbeBase—an online resource for rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:514-516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McGinness, S., and D. B. Johnson. 1992. Grazing of acidophilic bacteria by a flagellated protozoan. Microbiol. Ecol. 23:75-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller, W. L., K. Pabbaraju, and K. E. Sanderson. 2000. Fragmentation of 23S rRNA in strains of Proteus and Providencia results from intervening sequences in the rrn (rRNA) genes. J. Bacteriol. 182:1109-1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murray, R. G. E., K. H. Schleifer. 1994. Taxonomic notes—a proposal for recording the properties of putative taxa of prokaryotes. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 44:174-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Neefs, J. M., Y. Van de Peer, L. Hendriks, and R. De Wachter. 1990. Compilation of small ribosomal subunit RNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:2231-2241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Noller, H. F. 1984. Structure of ribosomal RNA. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 53:119-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pabbaraju, K., and K. E. Sanderson. 2000. Sequence diversity of intervening sequences (IVSs) in the 23S ribosomal RNA in Salmonella spp. Gene 253:55-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pronk, L. M., and K. E. Sanderson. 2001. Intervening sequences in rrn genes and fragmentation of 23S rRNA in genera of the family Enterobacteriaceae. J. Bacteriol. 183:5782-5787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rainey, F. A., N. L. Ward-Rainey, P. H. Janssen, H. Hippe, and E. Stackebrandt. 1996. Clostridium paradoxum DSM 7308T contains multiple 16S RNA genes with heterogeneous intervening sequences. Microbiology 142:2087-2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ralph, D., and M. McClelland. 1993. Intervening sequence with conserved open reading frame in eubacterial 23S rRNA genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:6864-6868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ralph, D., and M. McClelland. 1994. Phylogenetic evidence for horizontal transfer of an intervening sequence between species in a spirochete genus. J. Bacteriol. 176:5982-5987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Selenska-Pobell, S., and E. Evguenieva-Hackenberg. 1995. Fragmentations of the large-subunit rRNA in the family Rhizobiaceae. J. Bacteriol. 177:6993-6998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Skurnik, M., and P. Toivanen. 1991. Intervening sequences (IVSs) in the 23S ribosomal RNA genes of pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica strains. The IVSs in Y. enterocolitica and Salmonella typhimurium have a common origin. Mol. Microbiol. 5:585-593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sogin, M. L., and J. H. Gunderson. 1987. Structural diversity of eukaryotic small subunit ribosomal RNAs-evolutionary implications. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 503:125-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Song, X. M., A. Forsgren, and H. Janson. 1999. Fragmentation heterogenecity of 23S ribosomal RNA in Haemophilus species. Gene 230:287-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Springer, N., W. Ludwig, R. Amann, H. J. Schmidt, H.-D. Gortz, and K.-H. Schleifer. 1993. Occurrence of fragmented 16S rRNA in an obligate bacterial endosymbiont of Paramecium caudatum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:9892-9895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stackebrandt, E., and B. M. Goebel. 1994. Taxonomic note: a place for DNA-DNA reassociation and 16S rRNA sequence analysis in the present species definition in bacteriology. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 44:846-849. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Van Camp, G., Y. Van De Peer, S. Nicolai, J.-M. Neefs, P. Vandamme, and R. De Wachter. 1993. Structure of 16S and 23S ribosomal RNA genes in Campylobacter species: phylogenetic analysis of the genus Campylobacter and presence of internal transcribed spacers. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 16:361-368. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Willems, A., and M. D. Collins. 1993. Phylogenetic analysis of Rhizobia and Agrobacteria based on 16S gene sequences. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 43:305-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zahn, K., M. Inui, and H. Yukawa. 1999. Characterization of a separate small domain derived from the 5′ end of 23S rRNA of an α-proteobacterium. Nucleic Acids Res. 21:4241-4250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]