Abstract

Better not to rush

Early clamping and cutting of the umbilical cord is widely practised as part of the management of labour, but recent studies suggest that it may be harmful to the baby. So should we now delay the clamping?

Early clamping of the cord was one of the first routine medical interventions in labour. Its place in modern births was guaranteed by its incorporation into the triad of interventions that make up the active management of the third stage of labour. The earliest references are clear about the other two components of active management—oxytocin to contract the uterus and prevent postpartum haemorrhage, and controlled cord traction to prevent retention of the placenta.1 But early cord clamping had no specific rationale, and it probably entered the protocol by default because it was already part of standard practice. When this package was shown to reduce postpartum haemorrhage in the 1980s early cord clamping became enshrined in the modern management of labour.

But it has not been accepted everywhere. In Europe, although 90% (1052/1175) of units recommend uterotonic prophylaxis, only 66% (770/1175) recommend early cord clamping and 41% (481/1175) recommend controlled cord traction.2 The rate of early cord clamping varies from 17% (4/23) of units in Denmark to 90% (98/109) in France.2

So what is the evidence behind cord clamping? For the mother, trials show that early cord clamping has no effect on the risk of retained placenta or postpartum haemorrhage.3 4 Evidence from a Cochrane review supports this result—prophylactic oxytocin reduces the risk of postpartum haemorrhage whether the rest of the active management package is adopted or not.5

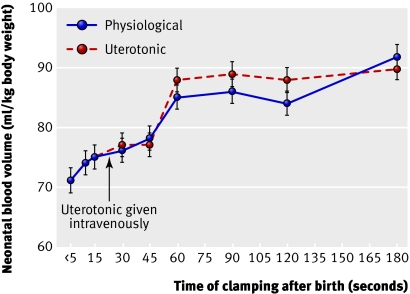

But what about the baby? Initially, the cord blood continues to flow, sending oxygenated blood back to the fetus while respiration becomes established, ensuring a good handover between the respiratory systems. At the time of the first fetal breath, however, the reduction in intrathoracic pressure draws blood into the lungs from the umbilical vein. So long as the cord is unclamped the average transfusion to the newborn is 19 ml/kg birth weight, equivalent to 21% of the neonate's final blood volume (figure).6 The final amount is unaffected by the use of oxytocics or the position of the baby relative to the placenta.6 7 Three quarters of the transfusion occurs in the first minute after birth. The rate of transfer can be increased by the use of intravenous uterotonics (to 89%), or by holding the newborn 40 cm below the level of the placenta.6 8

Changes in neonatal blood volume with increasing delay of cord clamping, with and without the use of a uterotonic. Adapted from the paper by Yao et al6

For the term baby, the main effect of this large autotransfusion is to increase iron status and shift the normal curve of the neonatal haematocrit to the right. This may be life saving in areas where anaemia is endemic. Here, late cord clamping increases the average haemoglobin concentration by 11 g/l at four months.9 In the developed world, however, there have been concerns that it could increase the risk of neonatal polycythaemia and hyperbilirubinaemia. Trials show this is not the case. Delayed cord clamping seems to drive up mean haematocrit values and serum concentrations of bilirubin, without increasing the number of infants needing treatment for jaundice or polycythaemia.7

For preterm babies the beneficial effects of delayed cord clamping may be greater. Although the studies are smaller, delayed clamping is consistently associated with reductions in anaemia, intraventricular haemorrhage, and the need for transfusion for hypovolaemia and anaemia.10 The one exception may be growth restricted babies who are already at risk of hypoxia induced polycythaemia.11

How should we approach cord clamping in practice? In normal deliveries, delaying cord clamping for three minutes with the baby on the mother's abdomen should not be too difficult. The situation is a little more complex for babies born by caesarean section or for those who need support soon after birth. Nevertheless, it is these babies who may benefit most from a delay in cord clamping. For them, a policy of “wait a minute” would be pragmatic.11 Indeed, this first minute is already largely spent on neonatal assessment. This could be done in warmed towels on the birthing bed or the mother's abdomen after vaginal delivery, or on the mother's legs at caesarean section. Cord clamping need only take place when transfer to the resuscitation trolley is required. For medicolegal purposes it will be important to document the time at which the cord was clamped, as delayed clamping reduces pH values in umbilical artery blood samples.12

There is now considerable evidence that early cord clamping does not benefit mothers or babies and may even be harmful. Both the World Health Organization and the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) have dropped the practice from their guidelines. It is time for others to follow their lead and find practical ways of incorporating delayed cord clamping into delivery routines. In these days of advanced technology, it is surely not beyond us to find a way of keeping the cord intact during the first minute of neonatal resuscitation.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; not externally peer reviewed

References

- 1.Spencer PM. Controlled cord traction in management of the third stage of labour. BMJ 1962;1:1728-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winter C, Macfarlane A, Deneux-Tharaux C, Zhang W-H, Alexander S, Brocklehurst P, et al. Variations in policies for management of the third stage of labour and the immediate management of postpartum haemorrhage in Europe. BJOG 2007;114:845-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oxford Midwives Research Group. A study of the relationship between the delivery to cord clamping interval and the time of cord separation. Midwifery 1991;7:167-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ceriani Cernadas JM, Carroli G, Pellegrini L, Otano L, Ferreira M, Ricci C, et al. The effect of timing of cord clamping on neonatal venous hematocrit values and clinical outcome at term: a randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics 2006;117:e779-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cotter A, Ness A, Tolosa J. Prophylactic oxytocin for the third stage of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2001;(4):CD001808. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Yao AC, Hirvensalo M, Lind J. Placental transfusion rate and uterine contraction. Lancet 1968;1:380-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hutton EK, Hassan ES. Late vs early clamping of the umbilical cord in full-term neonates. Systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials. JAMA 2007;297:1241-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yao AC, Lind J. Effect of gravity on placental transfusion. Lancet 1969;2:505-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Rheenen P, de Moor L, Eschbach S, de Grooth H, Brabin B. Delayed cord clamping and haemoglobin levels in infancy: a randomised controlled trial in term babies. Trop Med Int Health 2007;12:603-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rabe H, Reynolds G, Diaz-Rossello J. Early versus delayed umbilical cord clamping in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;(4):CD003248. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Van Rheenen PF, Brabin BJ. A practical approach to timing cord clamping in resource poor settings. BMJ 2006;333:954-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lievaart M, de Jong PA. Acid-base equilibrium in umbilical cord blood and time of cord clamping. Obstet Gynecol 1984;63:44-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]