Abstract

The suspected carcinogen 1,2-dichloroethane (1,2-DCA) is the most abundant chlorinated C2 groundwater pollutant on earth. However, a reductive in situ detoxification technology for this compound does not exist. Although anaerobic dehalorespiring bacteria are known to catalyze several dechlorination steps in the reductive-degradation pathway of chlorinated ethenes and ethanes, no appropriate isolates that selectively and metabolically convert them into completely dechlorinated end products in defined growth media have been reported. Here we report on the isolation of Desulfitobacterium dichloroeliminans strain DCA1, a nutritionally defined anaerobic dehalorespiring bacterium that selectively converts 1,2-dichloroethane and all possible vicinal dichloropropanes and -butanes into completely dechlorinated end products. Menaquinone was identified as an essential cofactor for growth of strain DCA1 in pure culture. Strain DCA1 converts chiral chlorosubstrates, revealing the presence of a stereoselective dehalogenase that exclusively catalyzes an energy-conserving anti mechanistic dichloroelimination. Unlike any known dehalorespiring isolate, strain DCA1 does not carry out reductive hydrogenolysis reactions but rather exclusively dichloroeliminates its substrates. This unique dehalorespiratory biochemistry has shown promising application possibilities for bioremediation purposes and fine-chemical synthesis.

1,2-Dichloroethane (1,2-DCA) is used as an intermediate of industrial polyvinyl chloride production. Due to leakage and improper disposal, this compound has become the most abundant chlorinated C2 groundwater pollutant on earth (the top five chlorinated and brominated C2 solvents based on average annual underground releases from 1988 to in the United States are 1,2-dichloroethane [136.6 tons/year], tetrachloroethene [9.2 tons/year], 1,2-dibromoethane [0.6 tons/year], 1,1,1-trichloroethane [0.5 tons/year], and trichloroethene [0.3 tons/year] [see “toxics release inventory” at U.S. Environmental Protection Agency website http://www.epa.gov/triexplorer/chemical.htm]). Due to its high water solubility (8 g/liter), its environmental half-life of 50 years in anoxic aquifers (28), and its probably carcinogenic effects (21), this pollutant poses a dispersing and long-lasting danger for humans and wildlife. Mostly, pump-and-treat technologies are too costly and time-intensive to remediate expanded contamination plumes, while oxidative in situ (bio)conversion is not compatible with the prevailing groundwater conditions. There is no reductive in situ (bio)remediation process for 1,2-DCA, as there is for many other chlorinated pollutants (1, 11, 16, 25), making its removal problematic.

1,2-DCA can undergo several cometabolic microbial and abiotic dechlorination reactions in anoxic habitats (Fig. 1), but these conversions are slow and incomplete (8, 27, 29). Only one isolated anaerobe, Dehalococcoides ethenogenes strain 195, can partially convert 1,2-DCA into ethene in an energy-conserving manner (16, 17), indicating a typically fast dehalorespiratory process (9). However, this overall dichloroelimination reaction concomitantly produces up to 1% carcinogenic vinyl chloride (VC) (15), while strain 195 depends on unknown bacterial extracts. Since VC is also dechlorinated by strain 195 under certain conditions in a cometabolic process, the possibility that this compound is an intermediate of the 1,2-DCA conversion cannot be excluded (18). In mixed bacterial cultures, the dichloroelimination of the analogous pollutant 1,2-dichloropropane (1,2-D) was linked to thus-far-uncultivated and unknown Dehalococcoides and Dehalobacter species (13, 14, 22, 23). So far, there have been no reports of characterized bacteria in defined media that completely dechlorinate 1,2-DCA or 1,2-D in a dehalorespiratory process without producing any chlorinated coproducts. We describe the isolation and characterization of a bacterium that fulfills these criteria for 1,2-DCA, 1,2-D, and other chloroalkanes. The bacterium, which has possible environmental applications, is the first to link dehalorespiration to stereochemistry.

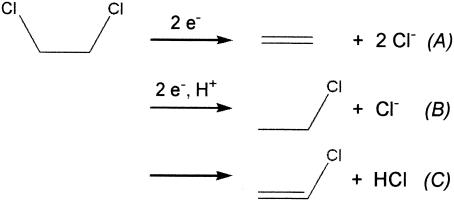

FIG. 1.

Possible dechlorination reactions of 1,2-DCA in anoxic habitats: dichloroelimination (A), reductive hydrogenolysis (B), and dehydrochlorination (C).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial inoculum and growth media.

The starting bacterial inoculum was obtained from the soil matrix of an anoxic water-saturated layer (1 m in depth) that had been exclusively polluted with 1,2-DCA (50 mg/kg) for 30 years (soil under an industrial storage tank containing 1,2-DCA). No other chlorinated substrates were present. The inoculum (1%, wt/vol) was transferred to sterilized anaerobic media containing 40 mM electron donor, 400 μM 1,2-DCA (sole electron acceptor since CO2 could not be reduced by strain DCA1), 0.02% (wt/vol) yeast extract (YE), vitamins [300 nM vitamin B1, 800 nM vitamin B3, 40 nM vitamin B7, 40 nM vitamin B12, 300 nM vitamin H1, 100 nM Ca-d(+)-pantothenate, 600 nM pyridoxamine · 2HCl], trace elements (20 nM N2SeO3·5H2O, 10 nM Na2WO4·2H2O, 7.2 μM FeSO4·7H2O, 1 μM ZnCl2, 0.2 μM boric acid, 20 nM CuCl2·2H2O, 0.2 μM NiCl2·6H2O, 0.3 μM Na2MoO4·2H2O), salts (0.2 mM MnCl2·4H2O, 0.5 mM Na2SO4, 1 mM CaCl2·2H2O, 7 mM KCl, 16 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2·6H2O, 5 mM NH4Cl, 2 mM KH2PO4), cysteine·HCl (1 mM), resazurin (2 mg/liter), and NaHCO3 (50 mM). After enrichment and isolation, suitable electron donors (40 mM) for strain DCA1 were H2 (40 mM, nominal concentration), formate, and lactate. Media with H2 or formate additionally contained 5 mM acetate (carbon source). Replacing YE by a defined mixture of amino acids (R7131 RPMI 1640; Sigma-Aldrich, Bornem, Belgium) and supplying 1 μM vitamin K1 or vitamin K2 (stock solution of 5 mM in pure isopropanol) allowed indefinite subcultivation of strain DCA1 under completely defined conditions.

Analysis.

Chlorinated substrates and alkenes were identified and quantified by headspace analysis or, after extraction in hexane, by gas chromatography with a flame ionization detector (Chrompack 9002) and a CP-SIL 5CB-MS capillary column (50 m by 0.32 mm; 1.2-μm stationary phase) and with a mass spectrometer (Varian 3400; Magnum Finnigan). Stereochemical conversion products of 2,3-dichlorobutane (DCB) stereoisomers were additionally analyzed with a Varian 3800 gas chromatograph with Poraplot Q column (25 m by 0.53 mm; 20-μm stationary phase) and a thermal conductivity detector. Inorganic anions were quantified on a Dionex ion chromatograph with an AS9-HC column (9 mM Na2CO3 eluent).

Phylogenetic data.

The 16S rRNA genes from a DNA extract (2) of a 50-ml pure culture were amplified, purified, and sequenced by PCR (12) using primers 16F27 (forward) and 16R1522 (reverse) with hybridizing positions 8 to 27 and 1541 to 1522, respectively, referring to Escherichia coli 16S rRNA gene sequence numbering (12). Phylogenetic analysis was performed using the Bionumerics software package (Applied Maths) after including the consensus sequences in an alignment of small ribosomal subunit sequences collected from GenBank. Comparison of the last 1,467 nucleotides of the amplified product of the 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) of strain DCA1 (accession no. AJ565938) with the sequences currently available from the EMBL database (Heidelberg, Germany) revealed a 96.6% similarity to the closest relative, Desulfitobacterium hafniense DCB-2 (DSM 10664; type strain). Multiple alignment was calculated with an open gap penalty of 100% and a unit gap penalty of 0%. A tree was constructed by the neighbor-joining method (analyzed and interpreted by the BCCM/LMG Bacteria Collection, Ghent, Belgium).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Initially, we focused on enrichment experiments with 1,2-DCA as the sole electron acceptor (besides CO2 present in these media). Therefore, a bacterial inoculum was transferred from soil that had been polluted with 1,2-DCA since 1970. After nine transfers with H2 as the electron donor and acetate as the carbon source, an unusually high 1,2-DCA dechlorination rate of 1.3 mM/day was achieved in the absence of methanogenesis and acetogenesis (no CO2 consumption). Stoichiometric amounts of ethene and HCl were produced.

We started isolation on agar (3%, wt/wt) media in roll tubes containing H2 as the electron donor and 1,2-DCA as the electron acceptor. About 3% of all transfers of single colonies to liquid media containing H2, 1,2-DCA, and 0.02% (wt/wt) YE resulted in dechlorination activity. Surprisingly, these dechlorinating cultures contained two different types of bacteria: a coccus and a curved rod. The coccus could be isolated from this bibacterial culture and was identified as an Enterococcus casseliflavus strain. This organism showed no dechlorination capacity. Hence, it was assumed that the curved rod was the dechlorinating organism.

A liquid medium dilution series of the bibacterial culture suggested a synergistic interaction between E. casseliflavus and the curved rod. Growth and dechlorination were observed only in dilution cultures containing both types of bacteria. Indeed, media that only contained the curved rod, which was visible under the microscope, did not support growth unless 50% (by volume) sterile filtered supernatant of anaerobically grown E. casseliflavus was added to these cultures. This addition resulted in growth and dechlorination activity, hence allowing isolation and physiological characterization of the curved rod, designated strain DCA1. No contaminating bacteria could be detected after cultivation in roll tubes containing 0.1% YE, 40 mM pyruvate, or 40 mM glucose or after aerobic cultivation on brain heart infusion agar plates.

Formate could replace H2 as an electron donor in the presence of acetate. However, acetate alone did not support 1,2-DCA dechlorination, indicating that it exclusively served as a carbon source. In addition, lactate could be used as electron donor and carbon source, making the addition of acetate unnecessary. Inorganic electron acceptors that sustained growth of strain DCA1 were SO32−, S2O32−, and NO3−. No growth was observed with the electron acceptors SO42−, NO2−, CO2, and fumarate. The supernatant of the E. casseliflavus culture was strictly required for growth of strain DCA1 with any electron acceptor but could not be replaced by YE, amino acids, 100 μM Fe2+, water-soluble vitamins, or volatile fatty acids.

To identify the unknown excretion product, other Enterococcus strains such as E. casseliflavus LMG 12901, Enterococcus faecalis LMG 11207, and Enterococcus avium LMG 10774 were additionally tested. Interestingly, the supernatant of the first two of these strains allowed growth of strain DCA1, while that of the E. avium strain did not. It has been reported that both E. casseliflavus and E. faecalis produce menaquinones, in contrast to E. avium (5). In our tests, indeed, 1 μM vitamin K1 or vitamin K2 could replace the Enterococcus supernatant and supported growth and dechlorination. In addition, a defined mixture of amino acids could replace the YE. Pure cultures of strain DCA1 could be subcultured indefinitely in these completely defined growth media with S2O32− or 1,2-DCA as the sole electron acceptor. It would be interesting to investigate if menaquinones are also essential for growing other dechlorinators, such as Dehalococcoides and Dehalobacter strains that are difficult to cultivate (13, 14, 16, 22, 23).

When we added 1,2-DCA, acetate, and 0.01% YE to media containing 1 μM vitamin K2, growth and dechlorination started but rapidly ceased (Fig. 2). The addition of an electron donor, such as H2, formate, or lactate, to these media sustained growth and supported dechlorination of up to 6 mM (cumulative) 1,2-DCA. YE was not required for growth and dechlorination but stimulated both and could be replaced by amino acids. Since H2 oxidation and 1,2-DCA reduction cannot be coupled to substrate level phosphorylation, the utilization of these substrates as sole energy sources in defined media indicates energy conservation via dehalorespiration in strain DCA1. The 1,2-DCA dechlorination rate exceeded 350 nmol of chloride released per min per mg of total bacterial protein, while the protein yield was 0.41 ± 0.08 g (mean ± standard deviation; n = 12 cultures) of total bacterial protein per mol of chloride released.

FIG. 2.

H2 and formate as electron donors for the dechlorination of 1,2-DCA, as reflected in the corresponding ethene production (A) and bacterial protein increase (B). Acetate (5 mM) was added in all media as a carbon source. The initial concentration of yeast extract was 0.01% (wt/vol). Measurements are average values of triplicate experiments. In identical media without H2 or formate, growth and dechlorination ceased after about 700 μM 1,2-DCA conversion. 1,2-DCA was respiked after complete conversion to ethene, leading to a cumulative nominal concentration of 4.8 mM (all five spikes) in media containing H2 or formate and to 1.2 mM (first two spikes) in media without an additional electron donor.

In addition to 1,2-DCA, a defined range of other chlorinated alkanes sustained growth of strain DCA1, including 1,2-D, 1,2-DCB, d-2,3-DCB, l-2,3-DCB, and meso-2,3-DCB. All these substrates (400 μM) were completely dechlorinated to the corresponding alkenes with at least 99.9% molar selectivity. Final concentrations of the substrates dropped below 2 μM. The toxicity limit of 1,2-DCA was found to be 1.5 mM during exponential growth. After six consecutive 5% (by volume) transfers on media containing S2O32− (10 mM) as the sole electron acceptor, strain DCA1 immediately started to dechlorinate vicinal dichloroalkanes when transferred to media containing these compounds. Since preculturing strain DCA1 with S2O32− or dichloroalkanes as the sole utilizable electron source did not influence its subsequent dechlorination behavior, these experiments indicate a constitutive dechlorination activity.

VC and monochloroethane were not used as electron acceptors, nor were they formed during 1,2-DCA dechlorination, indicating that neither of the compounds is a free intermediate of the process. In that sense, strain DCA1 is different from all dehalorespiring bacteria currently isolated because it neither dechlorinates any unsaturated chlorohydrocarbons nor carries out any reductive hydrogenolysis; strain DCA1 exclusively dichloroeliminates its saturated chlorosubstrates. This highly selective, fast, and energy-conserving dichloroelimination has not yet been described for a bacterial isolate in defined media, which suggests that the dichloroelimination mediated by strain DCA1 occurs via a novel type of biochemical reaction mechanism. The defined growth conditions of strain DCA1 and further research on its dehalogenase may allow the characterization of the currently unexplored respiratory dichloroelimination biochemistry.

More highly chlorinated alkanes such as hexa-, penta-, and tetrachloroethanes were not dichloroeliminated. However, 1,1,2-trichloroethane still supported growth producing VC, illustrating the exclusive dichloroelimination mechanism and suggesting that the catalytic center of the dehalogenase might be hindered when more than three chlorine substituents are present on both vicinal carbon atoms. Consistent with the exclusivity for dichloroeliminations, no chlorinated methanes, monochloroalkanes, or nonvicinal dichloroalkanes were dechlorinated. This illustrates a high substrate specialization, which is typical for most dehalorespiring bacteria. All substrates were tested at nontoxic levels. To ensure this lack of toxicity, cultures that did not start dechlorination of the substrates after 14 days were additionally supplemented with 400 μM 1,2-DCA. In all cases, direct conversion of 1,2-DCA and growth with this substrate occurred.

Phase-contrast light microscopy and scanning electron microscopy of the motile gram-positive cells of strain DCA1 revealed curved rods 0.5 to 0.7 μm in diameter and 2 to 5 μm in length. Occasionally, cell lengths exceeding 10 μm were observed. Optimal pH and temperature were 7.2 to 7.8 and 25 to 30°C, respectively. Reductive dechlorination occurred between 12 and 32°C.

Comparative analysis of the almost complete 16S rDNA sequence of strain DCA1 with the sequences currently available from the EMBL database revealed a 96.6% similarity to the closest relative, Desulfitobacterium hafniense strain DCB-2 (DSM 10664; type strain). Physiologically, strain DCA1 is clearly different from other Desulfitobacterium species, since chloroethenes and chlorophenols were not converted, while no other Desulfitobacterium species has been reported to mediate dichloroelimination of vicinal dichloroalkanes. One isolate, Desulfitobacterium sp. strain Y51, is able to partially dechlorinate hexa-, penta-, and tetrachloroethanes, in addition to partial polychloroethane dechlorination (26). This anaerobe uses both reductive hydrogenolysis and dichloroelimination reactions, which are slower and which produce chlorinated end products (dichloroethenes). Strain Y51 and strain DCA1 do not have any chlorosubstrate in common and show a 16S rDNA similarity of 96.0%. Strain DCA1 has been deposited in the BCCM/LMG Bacteria Collection (accession no. P21439) and has been proposed as the type strain of the new species Desulfitobacterium dichloroeliminans.

Strain DCA1 is not extremely oxygen sensitive, surviving aerobic conditions for at least 24 h, even though anoxic conditions (lower than −180 mV) were essential for 1,2-DCA dechlorination. Vitamin B12 (40 nM) was required as a growth supplement for significant dechlorination activity of strain DCA1. Propyl iodide (50 μM) completely inhibited dechlorination in the dark; the inhibition could be reversed by illumination. These findings provide strong evidence for the involvement of a corrinoid in the dichloroelimination reaction (19, 20).

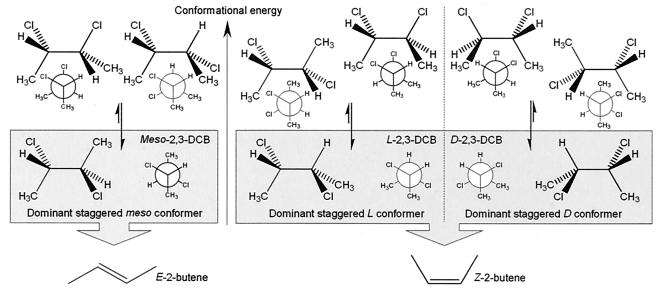

In vivo studies with three different 2,3-DCB stereoisomers as electron acceptors were performed (Fig. 3). The meso stereoisomer was selectively converted to E-2-butene, while both d and l enantiomers produced Z-2-butene. Interestingly, in the most stable staggered conformational isomers (conformers) of the meso compound and both dl compounds, both chlorine atoms are opposite to each other (transantiparallel position). Hence, the product pattern indicates a stereoselective anti dichloroelimination. The less-stable eclipsed meso and dl conformers, rarely observed below 303 K (30°C), would require a syn dichloroelimination on vicinal adjacent chlorine atoms, resulting in the opposite product formation (except for the highest-energy eclipsed dl conformers). Moreover, the high dechlorination rate, comparable with those for dehalogenases catalyzing reductive hydrogenolysis reactions, suggests that the most probable conformer is the main substrate of the dehalogenase of strain DCA1. To our knowledge, so far no stereoselective anti dichloroelimination of vicinal dichloroalkanes in mild aqueous conditions at ambient temperatures has been reported (3, 4, 6, 10, 24).

FIG. 3.

Suggested anti dichloroelimination mechanism catalyzed by strain DCA1 based on the stereoselective production of E- and Z-2-butene from the meso and dl stereoisomers of 2,3-DCB, respectively. Products formed result from the dichloroelimination of transantiparallel chlorine substituents on the saturated carbon chain. This position is always present in the most stable conformers. Newman projections are left view for meso and l isomers and right view for the d isomer.

The exclusive anti dichloroelimination of strain DCA1 makes its dechlorination biochemistry distinct from that of all other known dehalorespiring isolates. The evolution of the dehalogenase catalyzing this reaction is enigmatic. Natural production of trace amounts of strain DCA1's chlorosubstrates is not likely to provide sufficient selective evolutionary pressure in a geological time frame (7). In contrast, the observation that the polyvinyl chloride production intermediate 1,2-DCA is the anthropogenic chlorinated C2 solvent most massively released to groundwater during the last decades rather suggests a rapid dehalogenase development in response to environmental contamination.

The unraveled nutritional requirements of strain DCA1 allowed cultivation of the organism at 100-liter scale in pure culture. In situ pilot tests showed that the addition of 1 g (dry weight) of cells of strain DCA1 to 1 m3 of groundwater containing 1,2-DCA resulted in a complete detoxification within 1 week. Hence, dichloroelimination of dehalorespiring bacteria can be considered a highly efficient and unique remediation tool.

We presented the isolation, characterization, and growth medium definition of a dehalorespiring bacterium that selectively and completely dichloroeliminates several vicinal dichlorinated alkanes, including 1,2-DCA and 1,2-D. Besides environmental and stereoselective fine-chemical applications, this discovery may contribute to the understanding of respiratory dichloroelimination biochemistry and evolutionary dehalorespiration. The methods described in this report and the key role of menaquinone in the metabolism of strain DCA1 may help to isolate other dehalorespirers that perform a complete dechlorination.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge fellowships from the European Science Foundation (Gpoll) and Bijzonder Onderzoeksfonds (S.D.W.); funding by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, the EC, and the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie (G.D.); and funding by Ghent University (H.V.L. and W.V.).

Christof Holliger and Alexander J. B. Zehnder are acknowledged for a critical review of the manuscript.

Patents are pending on this technology.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adrian, L., U. Szewzyk, J. Wecke, and H. Görisch. 2000. Bacterial dehalorespiration with chlorinated benzenes. Nature 408:580-583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boon, N., C. Marle, E. Top, and W. Verstraete. 2000. Comparison of the spatial homogeneity of physico-chemical parameters and bacterial 16S rRNA genes in sediment samples from a dumping site for dredging sludge. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 53:742-747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Butcher, T. S., and M. R. Detty. 1998. Debrominations of vic-dibromides with diorganotellurides. 2. Catalytic processes in diorganotelluride. J. Org. Chem. 63:177-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butcher, T. S., F. Zhou, and M. R. Detty. 1998. Debrominations of vic-dibromides with diorganotellurides. 1. Stereoselectivity, relative rates, and mechanistic implications. J. Org. Chem. 63:169-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collins, M. D., and D. Jones. 1979. The distribution of isoprenoid quinones in streptococci of serological groups D and N. J. Gen. Microbiol. 114:27-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garst, J. F., J. A. Pacifici, V. D. Singleton, M. F. Ezzel, and J. I. Morris. 1975. Dehalogenations of 2,3-dihalobutanes by alkali naphthalenes. A CIDNP and stereochemical study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 97:5242-5249. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gribble, G. W. 1994. The natural production of chlorinated compounds. Environ. Sci. Technol. 28:310A-319A. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Holliger, C., G. Schraa, E. Stupperich, A. J. M. Stams, and A. J. B. Zehnder. 1992. Evidence for the involvement of corrinoids and factor F430 in the reductive dechlorination of 1,2-dichloroethane by Methanosarcina barkeri. J. Bacteriol. 174:4427-4434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holliger, C., G. Wohlfarth, and G. Diekert. 1998. Reductive dechlorination in the energy metabolism of anaerobic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 22:383-398. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuivila, H. G., and Y. M. Choi. 1979. Elimination and substitution in the reactions of vicinal dihalides and oxyhalides with trimethylstannylsodium. Effects of solvent and of ion aggregation on course and stereochemistry. J. Org. Chem. 44:4774-4781. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee, M. D., J. M. Odom, and R. J. Buchanan. 1998. New perspectives on microbial dehalogenation of chlorinated solvents: insights from the field. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 52:423-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leisner, J. J., M. Vancanneyt, K. Levebvre, K. Vandemeulebroecke, B. Hoste, N. E. Vilalta, G. Rusul, and J. Swings. 2002. Lactobacillus durianis sp. nov., isolated from an acid-fermented condiment (tempoyak) in Malaysia. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 52:927-931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Löffler, F. E., J. E. Champine, K. M. Ritalahti, S. J. Sprague, and J. M. Tiedje. 1997. Complete reductive dechlorination of 1,2-dichloropropane by anaerobic bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:2870-2875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Löffler, F. E., and K. M. Ritalahti. 2001. 16S rDNA based tools identify Dehalococcoides populations in many reductively dechlorinating enrichment cultures. Schriftenr. Biol Abwasserreinigung TU Berlin 15:53-68. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Magnuson, J. K., M. F. Romine, D. R. Burris, and M. T. Kingsley. 2000. Trichloroethene reductive dehalogenase from Dehalococcoides ethenogenes: sequence of tceA and substrate range characterization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:5141-5147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maymo-Gatell, X., Y. T. Chien, J. M. Gossett, and S. H. Zinder. 1997. Isolation of a bacterium that reductively dechlorinates tetrachloroethene to ethene. Science 276:1568-1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maymo-Gatell, X., T. Anguish, and S. H. Zinder. 1999. Reductive dechlorination of chlorinated ethenes and 1,2-dichloroethane by “Dehalococcoides ethenogenes” strain 195. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:3108-3113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maymo-Gatell, X., I. Nijenhuis, and S. H. Zinder. 2001. Reductive dechlorination of cis-1,2-dichloroethene and vinyl chloride by “Dehalococcoides ethenogenes. ” Environ. Sci. Technol. 35:516-521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neumann, A., G. Wohlfarth, and G. Diekert. 1995. Properties of tetrachloroethene and trichloroethene dehalogenase of Dehalospirillum multivorans. Arch. Microbiol. 163:276-281. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neumann, A., A. Siebert, T. Trescher, S. Reinhardt, G. Wohlfarth, and G. Diekert. 2002. Tetrachloroethene reductive dehalogenase of Dehalospirillum multivorans: substrate specificity of the native enzyme and its corrinoid cofactor. Arch. Microbiol. 177:420-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Premaratne, S., M. Mandel, and H. F. Mower. 1995. Detection of mutagen specific adduct formation in DNA using sequencing methodology. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 27:789-794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schlötelburg, C., F. von Wintzingerode, and U. B. Göbel. 2001. Structure and dynamics of an anaerobic 1,2-dichloropropane dechlorinating bioreactor culture. Schriftenr. Biol. Abwasserreinigung TU Berlin 15:107-125. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schlötelburg, C., C. von Wintzingerode, R. Hauck, F. von Wintzingerode, W. Hegemann, and U. B. Göbel. 2002. Microbial structure of an anaerobic bioreactor population that continuously dechlorinates 1,2-dichloropropane. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 39:229-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strunk, R. J., P. M. DiGiacomo, K. Aso, and H. G. Kuivila. 1970. Free-radical reduction and dehalogenation of vicinal dihalides by tri-n-butyltin hydride. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 92:2849-2856. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun, B., M. Griffin, H. L. Ayala-del-Río, S. A. Hashsham, and J. M. Tiedje. 2002. Microbial dehalorespiration with 1,1,1-trichloroethane. Science 298:1023-1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suyama, A., R. Iwakiri, K. Kai, T. Tokunaga, N. Sera, and K. Furukawa. 2001. Isolation and characterization of Desulfitobacterium sp. strain Y51 capable of efficient dehalogenation of tetrachloroethene and polychloroethanes. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 65:1474-1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Eekert, M. H. A., A. J. M. Stams, J. A. Field, and G. Schraa. 1999. Gratuitous dechlorination of chloroethanes by methanogenic granular sludge. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 51:46-52. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vogel, T. M., C. S. Criddle, and P. L. McCarty. 1987. Transformations of halogenated aliphatic compounds. Environ. Sci. Technol. 21:722-736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wild, A. P., W. Winkelbauer, and T. Leisinger. 1995. Anaerobic dechlorination of trichloroethene, tetrachloroethene and 1,2-dichloroethane by an acetogenic mixed culture in a fixed-bed reactor. Biodegradation 6:309-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]