Summary

Protein phosphorylation ensures the accurate and controlled expression of the genome, in particular by regulating the activities of pre-mRNA splicing factors. Here we report that Splicing Factor 1 (SF1), which is involved in an early step of intronic sequence recognition, is highly phosphorylated in mammalian cells on two serines within an SPSP motif at the junction between its U2AF65 and RNA binding domains. Interaction of the protein kinase KIS with SF1 through its “U2AF Homology Motif” (UHM) domain is necessary for its efficient phosphorylation of SF1 on these sites. Importantly, phosphorylation of SF1 on the SPSP motif leads to increased binding to U2AF65 and enhanced formation of the ternary U2AF65-SF1-RNA complex, suggesting an important role of this phosphorylation event in the function of SF1 and possibly in the structural rearrangements associated with spliceosome assembly and function.

Keywords: Protein phosphorylation, RNA splicing, U2AF-homology-motif

Introduction

The expression of the genome requires the precise and controlled removal of intervening sequences within pre-messenger RNAs (pre-mRNA splicing). Assembly of the active spliceosome requires successive rearrangements, including the entry and exit of molecular partners (reviewed in Ref. [1]). Phosphorylation events are likely molecular switches to control these conformational changes. Indeed, experiments with phosphatase inhibitors, purified phosphatases and nonhydrolysable ATP analogues have shown that multiple phosphorylation and dephosphorylation events are required for spliceosome assembly and splicing [2-4]. Among the best-characterized of the phosphorylated splicing factors are the SR protein family (reviewed in Ref.[5]), whose intranuclear distribution and activity is influenced by phosphorylation. Several specific kinases have been identified for SR protein phosphorylation, including SRPK1, SRPK2 [6,7], and Clk/Sty [8]. SF3b155/SAP155, an integral spliceosome component and substrate of cyclin E/CDK2 [9], is a non-SR protein whose phosphorylation state is regulated during the splicing process [10].

Splicing factor 1 (SF1) was independently identified as necessary for spliceosome assembly by in vitro reconstitution assays with protein fractions from HeLa nuclear extracts [11], and in a synthetic lethality screen with the yeast homologue of the splicing factor U2AF65 (Mud2p) [12]. Initially, SF1 binds to the branch point pre-mRNA consensus sequence (BPS) near the 3' splice site [13], and facilitates binding of the essential splicing factor U2 Auxiliary Factor large subunit (U2AF65) to the adjacent poly-pyrimidine tract pre-mRNA consensus (Py-tract) [14] by direct protein-protein interactions [15]. Next, SF1 is displaced from the spliceosome by the ATP-dependent entry of the U2 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particle (snRNP), whose SF3b155/SAP155 protein subunit interacts with U2AF65 [16] and RNA component (U2 snRNA) anneals with the BPS [17,18]. This first ATP-dependent step of 3' splice site recognition represents a critical juncture for regulation of pre-mRNA splicing. The protein kinase PKG is a potential regulator of this step, by inhibiting the SF1/U2AF65 complex upon phosphorylation of a conserved SF1 serine (Ser20) within its U2AF65 interaction domain [19].

The solution structure of the minimal SF1/U2AF65 complex [20] reveals that the U2AF65 domain belongs to a subclass of RNA recognition domains with specialized features for protein-protein interactions named U2AF Homology Motifs (UHM), based upon structural homology with the U2AF small subunit (U2AF35) [21,22]. Based on critical UHM features for interaction with the peptide ligands, diverse UHM-containing proteins were identified, including the mammalian protein kinase KIS [20,21]. The KIS polypeptide is organized into a kinase core followed by a C-terminal UHM motif [23-25], and preferentially phosphorylates Ser-Pro sites in vitro [26]. A role for KIS during control of cell-cycle division is supported by the phosphorylation of the nuclear CDK inhibitor p27kip1 [27] and the observation that KIS mRNA levels are misregulated in neurological tumors [23].

We report here that SF1 is phosphorylated on two major adjacent SerPro motifs (hereafter called the SPSP motif). We show that the protein kinase KIS can interact with SF1 through its UHM domain and efficiently phosphorylate SF1 on both serines of this SPSP motif, and therefore likely participates in controlling the phosphorylation state of SF1. Finally, SF1 SPSP motif phosphorylation enhanced its interaction with U2AF65 and formation of a ternary complex with U2AF65 and a model 3′ intronic sequence, suggesting the importance of these major phosphorylations in regulating SF1 function.

Results

Part I : Phosphorylation of SF1 on serines 80 and 82 in vitro and in vivo

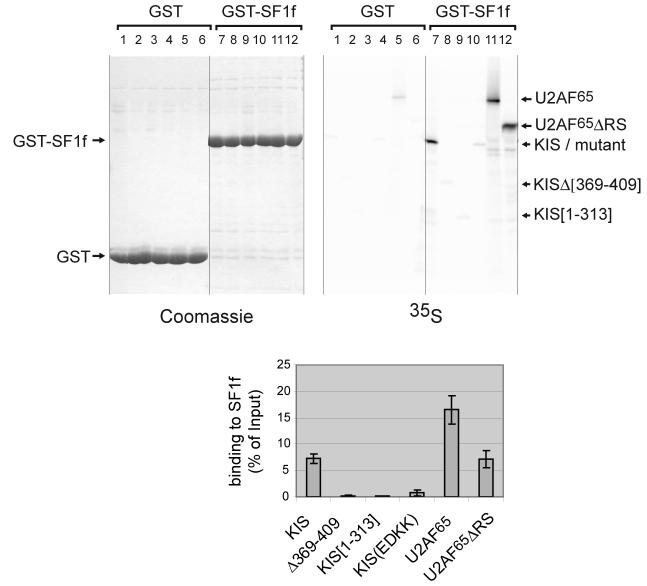

The presence of two adjacent SerPro motifs (aa 80-83, hereafter called SPSP motif) in a highly conserved region of splicing factor SF1 suggested that these serine residues could be targets of the proline directed kinase KIS whose UHM domain is a putative ligand for SF1. Furthermore, using pull-down experiments, we observed that KIS binds efficiently to a fragment of SF1 containing the SPSP motif (human SF1 residues 1-255, hereafter called SF1f) in vitro (Fig. 1). Interestingly, KIS binds SF1f as efficiently as U2AF65 lacking its RS domain (U2AF65ΔRS) (Fig. 1, compare lanes 7 and 12). In our conditions, binding of U2AF65ΔRS to SF1f was about twofold less than that of U2AF65 (lane 11) suggesting an unsuspected contribution of the RS domain of U2AF65 to SF1f binding. The possibility that the RS domain is necessary to stabilize the structure of the C-terminal domain could also explain this difference. A complete or a partial deletion of the UHM domain of KIS or mutations of two acidic residues (E341 and D342) to lysine in the putative A helix of the KIS UHM whose counterparts in U2AF65 have been shown to be required for binding to SF1 severely reduced binding to SF1f (lanes 8, 9 and 10). Therefore, when compared to U2AF65, KIS binds efficiently to SF1f and this interaction requires structural features of its UHM that are shared with U2AF65.

Figure 1. KIS interaction with SF1 in vitro.

Various methionine labelled forms of KIS and U2AF65 were tested for their binding to GST-SF1[1-255] (GST-SF1f) in a pull-down assay (top right, lanes 7-12). Lane 7: wildtype KIS; lane 8: KIS with a deletion within its UHM domain, KIS[Δ369-409]; lane 9: KIS lacking its UHM domain, KIS[1-313]; lane 10: KIS with mutations of E341 and D342 to lysine, KIS(EDKK), lane 11: full-length U2AF65 and lane 12: U2AF65 lacking its RS domain, U2AF65ΔRS. Background binding on GST beads was analysed (lanes 1-6) and 0.5% of starting material was run in parallel to allow quantification (not shown). Mean values of three experiments are presented with standard deviations for binding to SF1f (bottom). The equivalent loading of the beads with GST and GST-SF1f was checked by Coomassie staining of the gel (top left).

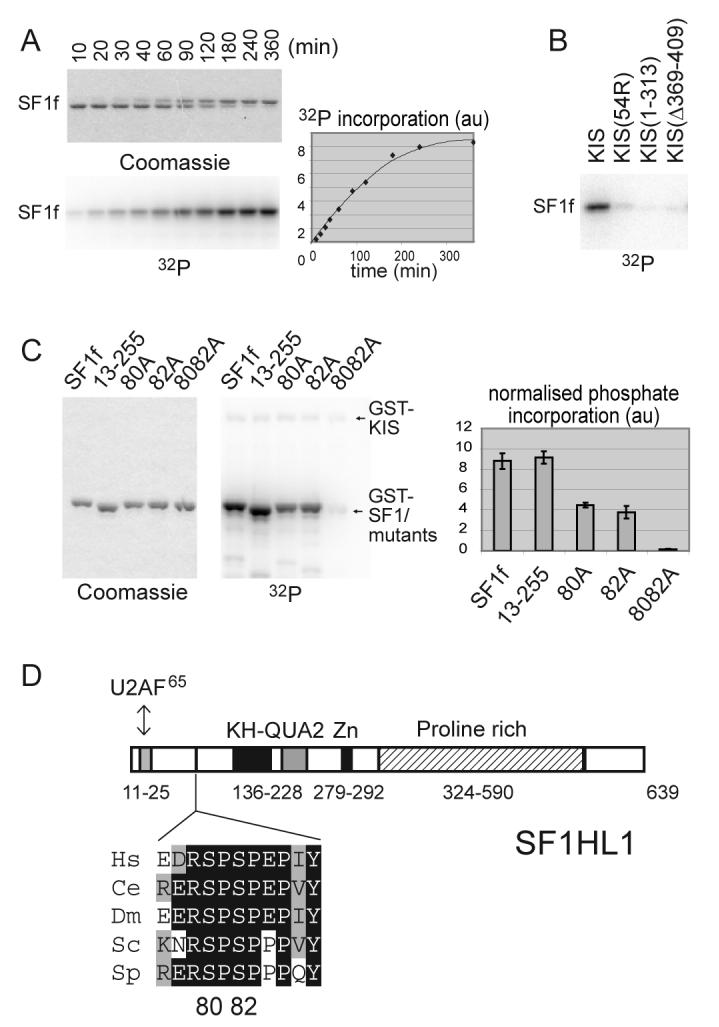

Kinase assays with recombinant KIS showed an efficient phosphorylation of SF1f, as evidenced by 32P phosphate incorporation and a marked shift of the SF1f band on SDS PAGE (Fig. 2A). The interaction of the UHM domain of KIS with SF1 appears important for efficient phosphorylation as deletions within the UHM domain of KIS prevented SF1f phosphorylation (Fig. 2B, lanes 3 and 4). In all conditions tested, phosphate incorporation never exceeded an evaluated stoichiometry of two phosphates for one SF1f molecule indicating that phosphorylation occurs on two residues. By mass spectrometry analysis, following tryptic digestion of SF1f phosphorylated to high stoichiometry (over 1.5 phosphates per SF1 molecule), we identified masses corresponding to peptide 67-92 and peptide 80-92, each with two phosphates. These peptides contain serines 80 and 82 in the putative KIS target SPSP motif. Phosphorylation velocity decreased by approximately two-fold when using SF1f with serine 80 or serine 82 mutated to alanine (Fig. 2C), indicating that KIS can phosphorylate both sites with similar efficiency whereas the double alanine mutation completely inhibited phosphorylation indicating that no phosphorylation occurs outside the SPSP motif. Altogether, KIS can phosphorylate SF1f on serine 80 and 82 with a high efficiency that particularly relies on the anchoring of its UHM domain to SF1. The respective involvement of KIS and other kinases and phosphatases in controlling the SF1 SPSP motif phosphorylation will need important studies. However interestingly, in the following report, KIS reveals itself a very powerful tool to demonstrate the major in vivo phosphorylation of the SPSP motif of SF1 as well as associated modifications of its interacting properties.

Figure 2. KIS phosphorylates SF1 in vitro on serines 80 and 82.

A) SF1[1-255] (SF1f) was phosphorylated by KIS with 10 μM [γ-32P]ATP for the indicated times. Reaction products were analysed by SDS PAGE, Coomassie blue staining and phosphorimaging. Phosphorylation of SF1f induced a shift of the SF1f band on SDS-PAGE.

B) The ability of similar amounts of the indicated forms of KIS to phosphorylate SF1f in vitro was compared, showing that deletion of or within the UHM domain of KIS impaired SF1f phosphorylation.

C) Phosphorylation in vitro of different forms of GST-SF1f as indicated. Reactions were stopped while phosphate incorporation was still linear with time (See “Experimental Procedures”). Mutation of both serines 80 and 82 completely abolished phosphate incorporation. Quantification: mean values of three experiments.

D) Primary structure of the SF1 isoform SF1HL1 (Alternatively spliced forms of SF1 differs by the length and sequence of their proline rich C-terminal region [28,51]). The SPSP motif is located in between the N-terminal U2AF65 binding region and the KH-QUA2 domain that mediates recognition of the BPS [20,52]. The SPSP motif is in a highly phylogenetically conserved region as presented in the alignment [15]. The sequences of SF1 are from the following organisms Hs, Homo sapiens; Ce, Caenorhabditis elegans; Dm, Drosophila melanogaster; Sc, Saccharomyces cerevisiae; Sp, Schizosaccharomyces pombe.

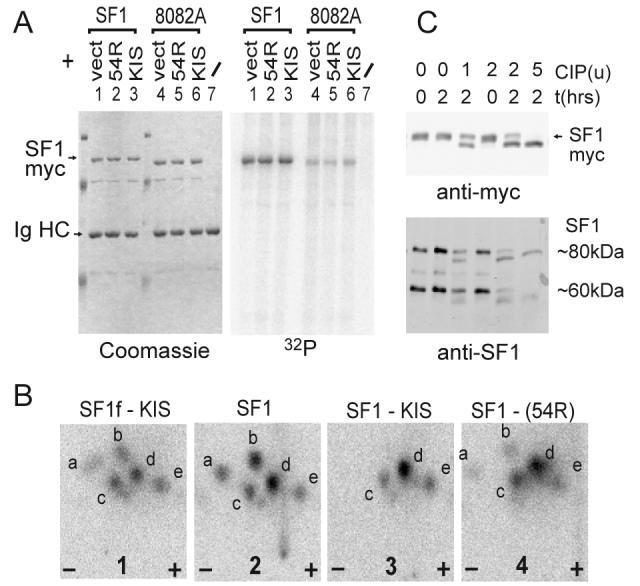

To determine whether the SPSP motif was phosphorylated in vivo, we performed metabolic labelling of HEK293 cells overexpressing SF1HL1myc (a major spliced form of SF1 [28], with a myc tag, hereafter SF1myc), followed by immunoprecipitation with antimyc antibody. As shown in Fig. 3A, mutation of SF1 on both serines 80 and 82 (hereafter called 8082A) dramatically reduced phosphate incorporation (about four-fold) showing that the SPSP motif contains major phosphorylation sites of SF1 in vivo. Remaining incorporated phosphate corresponds to phosphorylation on other sites like serine 20 which was shown to be phosphorylated in vivo [19].

Figure 3. SF1 SPSP motif phosphorylation in cells.

A) HEK293 cells were transfected with SF1myc or SF1myc(8082A) together with either pCDNA3 (vect), pCDNA3-KIS(54R) (kinase defective) or pCDNA3-KIS. Overexpressed SF1myc was immunoprecipitated with antimyc mAb 9E10 and analysed by SDS PAGE, coomassie staining (left) and phosphorimaging (right).

B) Phosphorylated SF1 was analysed by tryptic phosphopeptide mapping. Map 1: SF1f phosphorylated by KIS in vitro (with a moderate stoichiometry of about 0.1 phosphate per SF1 molecule). Maps 2, 3 and 4 : phosphorylated SF1myc from lanes 1, 3 and 2 of gel in A. SF1f and SF1myc present almost identical maps showing that major phosphorylation occurs on the SPSP motif in vivo. Coexpression of KIS leads to disappearance of the more basic a and b peptides (two experiments) indicating an increase in the phosphorylation state of the SPSP motif.

C) 5 μg of protein extract of HEK293 cells overexpressing SF1myc (top) or of untransfected HEK293 cells (bottom) were analysed by phosphatase (CIP) treatment with the different amounts indicated (units from New Englands Biolabs) and western blotting with antimyc or antiSF1 antibody (Cemines). In additional characterization experiments we showed that the 80kDa band migrated just below SF1myc, was nuclear and heat soluble which are characteristics of SF1 [53]. The 60kDa band most probably corresponds to a differentially spliced form [28].

To confirm the major phosphorylation of the SPSP motif, we compared the tryptic phosphopeptide map of SF1f phosphorylated in vitro by KIS to that of SF1myc phosphorylated in cells (Fig. 3B, maps 1 and 2). In fact, these peptide maps were highly similar. The tryptic peptide maps presented multiple spots corresponding to incomplete digestion by trypsin as previously observed by mass spectrometry analysis, and to the presence of single and double phosphorylation of the peptides as suggested by our analysis of SF1f phosphorylated in vitro by KIS to different extents (data not shown). Co-expression of KIS did not obviously increase the incorporation of radioactive phosphate (Fig. 3A, lane 3), but phosphopeptide mapping revealed its effect to increase the proportion of more acidic peptides (c, d, e) (Fig. 3B, compare maps 2, 3) suggesting that it increases the phosphorylation state of SF1 on the SPSP motif. Coexpression with KIS(54R), a mutation within the kinase active site that suppresses activity [24], had an intermediate effect (Fig. 3B, map 4). This agreed with our unpublished observations that KIS(54R) retains low levels of kinase activity towards SF1, due to the unusually high activity of KIS for this substrate.

The observation that wild type SF1myc migrates slower than the 8082A mutant (compare lanes 1-3 with 4-6 in Fig. 3A) further indicated that the SPSP motif of SF1 is mostly in a phosphorylated state in proliferating HEK293 cells. We tested this possibility by treating nuclear extracts of SF1myc overexpressing cells with alkaline phosphatase. As shown in Fig. 3C, phosphatase treatment induced a faster migration of SF1myc on SDS-PAGE showing that SF1myc is on average highly phosphorylated in proliferating cells. This was also the case for endogenous forms of SF1 in HEK293 (Fig 2C, lower panel) and HeLa cells (not shown).

To summarize, these analyses show that the SPSP motif contains major in vivo phosphorylation sites of SF1. In agreement with this result, two recent independent large scale analysis of the phosphoproteome, one in nuclear extract of HeLa cells, the other in WEHI-231 B lymphoma cells, lead to the identification of the same 67-92 peptide of SF1 phosphorylated on both Serines 80 and 82 [29,30]. Altogether, this high level of phosphorylation of its SPSP motif indicates a particular involvement in SF1 function.

Part II: Modulation of SF1 binding properties upon SPSP motif phosphorylation

The SPSP motif lies at the junction between the U2AF65 binding N-terminal region of SF1 and its RNA binding domain, suggesting that phosphorylation on these sites might modulate the formation of the SF1-U2AF-RNA complex.

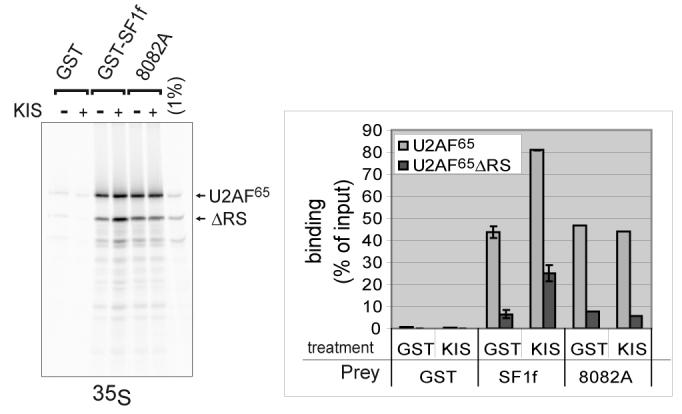

We first tested the effect of phosphorylation on the interaction of SF1 with U2AF65 by pull-down experiments. Using GST-SF1f that was phosphorylated by KIS to high stoichiometry (over 1.5 phosphate per SF1f molecule) we observed a two-fold increase in U2AF65 and a three-fold increase of U2AF65ΔRS binding (Fig. 4). In contrast no increase in binding could be observed with the 8082A SF1f mutant upon treatment with KIS, showing that phosphorylation on the SPSP motif is responsible for U2AF65 binding enhancement.

Figure 4. SF1 SPSP motif phosphorylation enhances binding to U2AF65.

Pull-down experiments were performed using purified GST-SF1f or GSTSF1f-8082A that were phosphorylated by KIS (+) or mock phosphorylated (−). We used as input a mixture of in vitro translated methionine labelled U2AF65 and U2AF65ΔRS. We checked that interaction was the same when these proteins were alone or in the mixture (not shown). Interactions with GST-SF1f phosphorylated by KIS versus mockphosphorylated were in duplicates. Quantification was performed by phosphorimaging. The mean values with standard deviation are represented. Representative results of two experiments.

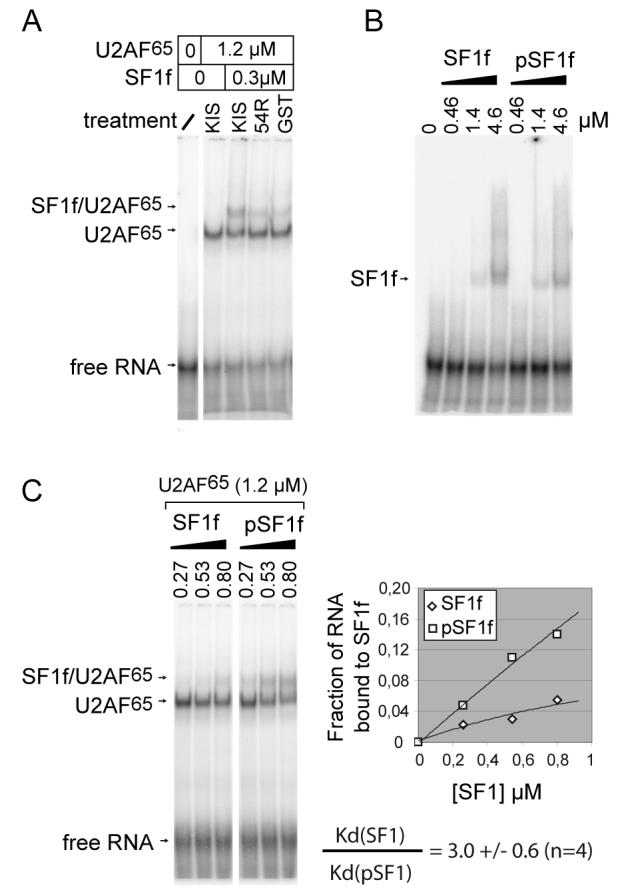

As SF1 and U2AF65 have been shown to bind in a cooperative manner to a model 3′ splice site RNA, we hypothesised that the modification of SF1 binding to U2AF65 could in turn modulate the formation of the SF1-U2AF65-RNA ternary complexes. We analysed the formation of this complex by RNA gel-shift. As shown in Fig. 6, the shifts of RNA induced by U2AF65, and SF1f plus U2AF65 binding were clearly identified as previously described by Berglund and coll. [14]. Interestingly we observed an increase in ternary complex formation (compare Fig. 5A, lanes 3, 4 and 5). In contrast, no major modification of SF1f alone binding to RNA was observed (Fig. 5B). Further analysis using increasing concentrations of SF1f or pSF1f with constant concentration of U2AF65 (1.2 μM) confirmed the enhancement of ternary complex formation with phosphorylated SF1 (Fig. 5C). This was observed using three different productions of phosphorylated SF1 versus parallel productions of mockphosphorylated SF1. The ratio of the apparent Kd were calculated by linear regression of the Hill plot for four experiments showing an about three fold decrease of apparent Kd for SF1 binding to RNA upon phosphorylation by KIS. To summarize, these results show that phosphorylation of SF1 on the SPSP motif enhances binding to U2AF65 and formation of the ternary SF1-U2AF65-RNA complex.

Figure 5. SF1 SPSP motif phosphorylation enhances formation of a SF1-U2AF65- RNA ternary complex.

A. We used a 32P labelled RNA oligonucleotide corresponding to a model 3′ intronic sequence previously characterized in gel-shift experiments with SF1 and U2AF65 (see Experimental Procedures) [14]. RNA was incubated with different protein mixtures. Single shift with U2AF65 and supershift with U2AF65 plus SF1f were clearly identified (lanes 2 and 3). Formation of SF1f-U2AF65-RNA complex was enhanced by previous phosphorylation of SF1f by KIS (compare lane 3 with lanes 4 and 5).

B. Increasing concentrations of SF1f or SF1f phosphorylated by KIS (pSF1f) showed no major difference in RNA shift.

C. To quantify the enhancement of formation of the SF1f-U2AF65-RNA complex upon phosphorylation of the SPSP motif, we used increasing concentrations of SF1f or SF1f phosphorylated by KIS (pSF1f) in the presence of 1.2 μM U2AF65. The different bands were quantify by phosphorimaging and we plotted the formation of the ternary complex as a fraction of total RNA. We determined the decrease of the apparent Kd of SF1 for RNA upon phosphorylation by KIS, by determining the y intercept of the Hill plot for each experiment (not shown). We used three different preparations of phosphorylated and mockphosphorylated SF1f in four experiments and found that phosphorylation induced an average 3 fold decrease of the apparent Kd of SF1 for RNA in the presence of 1.2μM U2AF65.

Discussion

Importance of the interaction of SF1 with U2AF65

A comprehensive set of data indicate the functional importance of the interaction of SF1 with U2AF65. In mammals, the interaction between U2AF65 and SF1 was demonstrated in two-hybrid, pulldown and farwestern assays [12,14,15]. These interactions involve the highly conserved N-terminus of SF1 and UHM domain of U2AF65. In addition, SF1 and U2AF65 were shown to be both present in the early spliceosomal complex E [12,31]. SF1 was shown to bind preferentially to the pre-mRNA branchpoint sequence [13,32] while U2AF65 interacts with the close pyrimidine tract and its RS domain contacts the branchpoint [33-36]. Furthermore the interaction of U2AF65 and SF1 with the branchpoint region were found to be cooperative [14]. Finally structural basis for this interaction were determined [20].

The SF1-U2AF65 interaction appears highly conserved through evolution. In S. pombe, SF1 and the U2AF subunits orthologs U2AF59 and U2AF23 form a stable complex [37]. In S. cerevisiae the SF1 ortholog Msl5p is highly conserved while the U2AF65 ortholog Mud2p shows a sequence conservation restricted to the UHM domain involved in its interaction with SF1. Like their mammalian counterparts, Msl5p and Mud2p interact and are recruited early in spliceosome assembly [38,39]. Msl5p has a marked preference for binding to the consensus S. cerevisiae branchpoint sequence [13] and Mud2p requires an intact branchpoint region for binding [38,40]. Furthermore MSL5 was identified by virtue of its genetic interaction with MUD2 [12].

In this context, our finding that the SF1-U2AF65 interaction can be enhanced by phosphorylation is most probably of importance for SF1 function. Importantly, SF1 is thought to perform an essential conserved function for cell viability. Actually, in HeLa cells, siRNA depletion of SF1 leads to cell death [41] and in S. cerevisiae MSL5 disruption is lethal [12].

However, despite the well-characterized role of U2AF65 in splicing, the strong evidence for the SF1-U2AF65 interaction taking place early during spliceosome formation and the fact that SF1 is necessary for spliceosome assembly in in vitro reconstitution assays with protein fractions from HeLa nuclear extracts [42], experimental perturbations of SF1 did not lead to major impairment of splicing of different pre-mRNA. Actually thorough immunodepletion of SF1 from a HeLa splicing extract only modestly reduced the kinetic of spliceosome assembly [43]. Similarly no differences in splicing in vitro for three substrates could be detected when complementing a U2AF65 depleted extract with full-length U2AF65 or U2AF65 lacking its UHM domain, suggesting that the SF1-U2AF65 interaction could be dispensable in vitro for splicing of at least a subset of pre-mRNA [44]. Using S. cerevisiae extracts depleted for SF1 or prepared from temperature-sensitive mutants grown at the non permissive temperature, no splicing defect of a pre-mRNA with consensus splice sites was detected, but splicing of pre-mRNA with weakened splice site sequences was reduced, suggesting that partial depletion of SF1 function at least affects splicing efficiency [39,45]. Finally, SF1 knockdown in HeLa cells using siRNA, although leading to cell death, did not apparently affect splicing of several pre-mRNA nor the levels of a variety of proteins translated from spliced mRNA [41]. The possibility that low levels of remaining SF1 in depleted extracts and in siRNA treated cells are sufficient for its transient catalytic action in prespliceosome assembly on most pre-mRNA has been proposed [39,41,45] thus leaving the possibility that SF1 has an essential role in splicing that could not be evidenced in these different conditions. In the conditions were SF1 function is repressed, a splicing defect of a subset of pre-mRNA for which SF1 is rate limiting, some of which encoding essential peptides has been proposed to explain its effect on cell viability [45]. Alternatively, a cumulative effect of modestly reduced kinetic in splicing of a larger subset of pre-mRNA leading to a deficiency of an essential function could explain the reported results. Finally, functions of SF1 other than splicing have been suggested that could be related to its requirement for cell viability. Namely, SF1 was found to bind transcription factors and to repress transcription in a reporter assay in mammalian cells [46,47]. In S. cerevisiae, Msl5p temperature-sensitive mutants at the non permissive temperature presented a pre-mRNA retention defect [45]. Interestingly in this context, U2AF65 has been shown to be a shuttling protein and its function in RNA export has been documented [48,49].

In conclusion further work is clearly needed to decipher the function of SF1 in splicing and other processes. Given the strong evidence supporting the conserved SF1-U2AF65 interaction, it is likely that the regulations of this interaction by phosphorylation of serine 20 [19] and of the highly conserved SPSP motif might be of major importance for the control of its function(s). Finally the identification of these phosphorylated forms of SF1 opens new possibilities to investigate its function.

Speculations concerning the functional and structural consequences of SPSP motif phosphorylation

The importance of the SF1 SPSP motif phosphorylation was first suggested to us by a very efficient phosphorylation of SF1 by the U2AF65 related protein kinase KIS whose C-terminus UHM domain is in fact the closest homolog of the UHM of U2AF65. Phosphorylation occurred exclusively on serine residues 80 and 82 within the SPSP motif. Interestingly we found that KIS can interact in vitro with SF1 as efficiently as U2AF65ΔRS and that its UHM domain is required for binding to and to phosphorylate SF1. KIS appears as a likely candidate for controlling the SF1 SPSP motif phosphorylation and its respective involvement and that of other kinases and of phosphatases in this control in vivo is the subject of further investigations.

Next we found that SF1 is on average highly phosphorylated on the SPSP motif in HEK293 cells. This was also the case in HeLa cells and mouse brain (data not shown). In fact the faster migrating unphosphorylated form of SF1 was undetectable without phosphatase treatment of the extracts. The functional significance of this major modification of SF1 was further suggested by the induced modification of its interaction with U2AF65. Actually in pulldown experiments, U2AF65 recovery on GST-SF1 beads was markedly enhanced when SF1 was phosphorylated by KIS (Fig. 4). In gel-shift experiments with a model 3′ splice site RNA, SF1 SPSP motif phosphorylation enhanced the formation of the ternary U2AF65-SF1-RNA complex leading to a marked decrease of the apparent Kd of SF1 for RNA in the presence of U2AF65 (Fig. 5). Finally, the SPSP motif is highly conserved as well as surrounding residues (Fig. 2D) suggesting that phosphorylation of this motif is a conserved mechanism for SF1 regulation.

In view of the discussed proposed functions for SF1, this phosphorylation event could be important for constitutive or alternative splice site selection by facilitating recognition of weak acceptor sequences, it could participate in the nuclear retention of pre-mRNA or participate in a control of transcription associated with prespliceosome assembly. The observed highly phosphorylated state of SF1 could reflect that SF1 dephosphorylation is transient for example for recycling of SF1 after prespliceosome assembly. It is tempting to speculate that dephosphorylation of SF1, by decreasing its affinity for U2AF65, might help the replacement of SF1 by the U2snRNP component SF3b155/SAP155. Interestingly, the fact that phosphorylation occurs at a distance from the U2AF65 binding domain suggests that the SPSP motif remains accessible to a regulating phosphatase when SF1 is bound to U2AF65 and RNA. This hypothesis is also supported by the fact that phosphorylation within proline rich regions are known to induce structural rearrangements [50] that could therefore propagate up to the U2AF65 binding site in the case of SF1. The observation by Rain and coll [15] that two alpha helices are predicted to form on each side of the proline-rich region containing the SPSP motif suggests that structural modifications at the SPSP region by phosphorylation could become amplified by these helical structures, thereby facilitating the SF1-U2AF65 interaction. However we cannot exclude that the phosphorylated serine residues directly participate in the interaction with U2AF65. Of note, analysis of binding of deleted forms of SF1 showing that residues downstream residue 25 were dispensable for interaction were performed with unphosphorylated SF1 [20]. Our data suggest that the phosphorylated SPSP do not interact with the basic RS domain because binding enhancement upon phosphorylation was also observed with U2AF65ΔRS. Further investigations are aimed at dissecting the structural basis for the effect of SPSP motif phosphorylation on the interaction of SF1 with U2AF65.

Altogether, the high level of phosphorylation of SF1 on the phylogenetically conserved SPSP motif in vivo, together with the associated modifications of its interactions properties strongly suggest a functional implication for SF1 function(s). Further studies will address the questions of whether and how RNA splicing and/or the other potential functions of SF1 in pre-mRNA retention or transcription repression are regulated by SF1 SPSP motif phosphorylation and by KIS.

Experimental procedures

Plasmids and mutagenesis

Plasmids for expression of human SF1 (residues 1-255) (SF1f) was constructed in the pGEX6P-1 vector (Pharmacia). SF1f contains the U2AF65 binding domain and KH-QUA2 domain for BPS recognition. Prior to PCR, the SF1 template was corrected for a Arg19Gly mutation inadvertently present from previous published work [14]. Plasmids pSP64-U2AF65 and U2AF65ΔRS (lacking aa 25 to 63) [33] for in vitro translation were kindly provided by J. Valcarcel. To allow expression of rat KIS from the same vector, an NcoI-XhoI blunt insert from plasmid BSKIS [24] was transferred to pSP64-U2AF65 NcoI-EcoRI blunt yielding pSP64-KIS. For expression in mammalian cells, SF1HL1 cDNA was amplified from cDNA of HeLa cells and subcloned in pCDNA3 with a myc tag at the C-terminal (SF1myc in the text). Site-directed mutagenesis was performed using Quickchange protocol from Stratagene.

Protein expression and purification

GST-KIS and mutants were produced as previously described [26]. GST-SF1f was purified by glutathione-affinity chromatography, followed by removal of GST using Precision Protease (Pharmacia) and further purification on SP-sepharose (Pharmacia). Purified fractions were frozen in 200 mM NaCl, 25 mM Hepes pH6.8, 20% v/v glycerol. Plasmid for U2AF65 was a gift of M. Green, and HIS-tagged protein was expressed in bacteria and purified using standard protocols.

GST pull-down

In vitro translations were performed using the TNT system (Pharmacia) and [35S]-methionine (NEN). For experiments in figure 1, 1 μl of in vitro translation product was mixed with 250 μl of GST or GST-SF1f extract corresponding to 5 ml of the BL21 cells cultures, in GSB buffer (25 mM Hepes pH7.5, 100 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% NP40 and 10% glycerol) with 1 mM DTT and antiprotease mix from Roche. For experiments in figure 4, in vitro translation products were incubated with 1 μg purified GST or GST-SF1 in the presence of 1 μg/μl BSA as a non specific competitor. After 90 min incubation at 4 °C, 10 μl of glutathione beads (Pharmacia) were added for a further 30 min, beads were washed rapidly 5 times with GSB buffer, and proteins were analysed by SDS-PAGE, Coomassie blue staining and phosphorimaging (Cyclone, Packard).

Phosphorylation reactions

Phosphorylation reactions were performed as described previously [26]. Briefly, 20 μl reactions contained approximately 20 ng recombinant GST-KIS and 1 μg of substrate in 50 mM MES pH 8.0, 10 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT, 2 mM EDTA, 25% glycerol, 10 μM [γ-32P]ATP (5 nCi/pmole) (NEN). For substrate and kinase mutant comparison we performed 30 minute reactions and checked the linearity of phosphate incorporation. For stoichiometric phosphorylation we performed 6 hour incubations with 0.4 mM ATP.

Mass spectrometry

After phosphorylation by KIS, SF1f was dialysed against NH3HCO3 50 mM pH 8.0, digested with trypsin, and HPLC reverse phase fractions were analysed with a FT-ICR mass spectrometer APEX III (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) equipped with a 7 Tesla supraconducting magnet and an infinity cell.

Metabolic labelling of cells

HEK293 cells were transfected using lipofectamine reagent (Invitrogen). After 24 hours, the medium was replaced with 1 ml methionine-free medium containing 1 mCi [32P]-inorganic phosphate (NEN) for 4 hours. Cells were lysed in immunoprecipitation buffer containing 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% nonidet P40, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT and protease inhibitors. Immunoprecipitation was performed with the monoclonal anti-myc 9E10 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Phosphopeptide mapping

Proteins were digested ‘in-gel’ overnight with trypsin at 30°C as previously described [26]. Eluted peptides were lyophilized and resuspended in electrophoresis buffer (pH 3.5). After electrophoresis and chromatography, plates were revealed by phosphorimaging.

Phosphatase treatment

Cell extracts (5 μg of proteins) were treated with the indicated amount of Calf Intestine Phosphatase (CIP) (New England Biolabs) for 2 hours.

RNA gel-shift assays

RNA oligonucleotide with sequence derived from the Adenovirus major late pre-mRNA (5'-UUCGUGCUGACCCUGUCCCUUUUUUUUCCACAGC-3') was synthesized by Dharmacon. 5′ labelling was performed with [γ-32P]ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase. Labelled RNA was purified on Nensorb20 column (NEN). About 10000 cpm/2 fmole of oligonucleotide was used with the indicated concentrations of purified proteins and with tRNA (0.5 μg/μl) as non specific competitor. Interactions were in 15 μl containing 25 mM Tris pH7.5, 90 mM NaCl and 1 mM EDTA, for 1 hour at room temperature. We checked that equilibrium was reached at this time point. The mixture was loaded on 6% acrylamide gels in 0.5xTBE buffer, and run at 4°C for 3 hours.

Acknowledgements

We thank colleagues from INSERM U706, D. Weil and J. Chamot-Rooke for stimulating discussion and support. We are grateful for the generous gifts of U2AF65 constructs from J. Valcárcel and M. Green, and SF1 cDNA from J. A. Berglund. We thank S. Lindley for technical assistance. This work was funded by the “Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale”, the “Université Pierre et Marie Curie” the “Association Française contre les Myopathies” and the “Association pour la Recherche contre le Cancer” to A.S. and A.M., and National Institutes of Health grant (GM070503-01) to C.L.K.

Abbreviations

- GST

glutathione-S-transferase

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- Hepes

4-(2-Hydroxyethyl)piperazine-1-ethanesulfonic acid

References

- 1.Brow DA. Allosteric cascade of spliceosome activation. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2002;36:333–360. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.36.043002.091635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mermoud JE, Cohen PT, Lamond AI. Regulation of mammalian spliceosome assembly by a protein phosphorylation mechanism. EMBO J. 1994;13:5679–5688. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06906.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mermoud JE, Cohen P, Lamond AI. Ser/Thr-specific protein phosphatases are required for both catalytic steps of pre-mRNA splicing. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:5263–5269. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.20.5263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tazi J, Kornstadt U, Rossi F, Jeanteur P, Cathala G, Brunel C, Luhrmann R. Thiophosphorylation of U1-70K protein inhibits pre-mRNA splicing. Nature. 1993;363:283–286. doi: 10.1038/363283a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stojdl DF, Bell JC. SR protein kinases: the splice of life. Biochem Cell Biol. 1999;77:293–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gui JF, Tronchere H, Chandler SD, Fu XD. Purification and characterization of a kinase specific for the serine- and arginine-rich pre-mRNA splicing factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:10824–10828. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.10824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang HY, Lin W, Dyck JA, Yeakley JM, Songyang Z, Cantley LC, Fu XD. SRPK2: a differentially expressed SR protein-specific kinase involved in mediating the interaction and localization of pre-mRNA splicing factors in mammalian cells. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:737–750. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.4.737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colwill K, Pawson T, Andrews B, Prasad J, Manley JL, Bell JC, Duncan PI. The Clk/Sty protein kinase phosphorylates SR splicing factors and regulates their intranuclear distribution. EMBO J. 1996;15:265–275. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seghezzi W, Chua K, Shanahan F, Gozani O, Reed R, Lees E. Cyclin E associates with components of the pre-mRNA splicing machinery in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:4526–4536. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.8.4526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang C, Chua K, Seghezzi W, Lees E, Gozani O, Reed R. Phosphorylation of spliceosomal protein SAP 155 coupled with splicing catalysis. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1409–1414. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.10.1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kramer A. Purification of splicing factor SF1, a heat-stable protein that functions in the assembly of a presplicing complex. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:4545–4552. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.10.4545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abovich N, Rosbash M. Cross-intron bridging interactions in the yeast commitment complex are conserved in mammals. Cell. 1997;89:403–412. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80221-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berglund JA, Chua K, Abovich N, Reed R, Rosbash M. The splicing factor BBP interacts specifically with the pre-mRNA branchpoint sequence UACUAAC. Cell. 1997;89:781–787. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80261-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berglund JA, Abovich N, Rosbash M. A cooperative interaction between U2AF65 and mBBP/SF1 facilitates branchpoint region recognition. Genes Dev. 1998;12:858–867. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.6.858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rain JC, Rafi Z, Rhani Z, Legrain P, Kramer A. Conservation of functional domains involved in RNA binding and protein-protein interactions in human and Saccharomyces cerevisiae pre-mRNA splicing factor SF1. RNA. 1998;4:551–565. doi: 10.1017/s1355838298980335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gozani O, Potashkin J, Reed R. A potential role for U2AF-SAP 155 interactions in recruiting U2 snRNP to the branch site. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:4752–4760. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.8.4752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu J, Manley JL. Mammalian pre-mRNA branch site selection by U2 snRNP involves base pairing. Genes Dev. 1989;3:1553–1561. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.10.1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhuang Y, Weiner AM. A compensatory base change in human U2 snRNA can suppress a branch site mutation. Genes Dev. 1989;3:1545–1552. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.10.1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang X, Bruderer S, Rafi Z, Xue J, Milburn PJ, Kramer A, Robinson PJ. Phosphorylation of splicing factor SF1 on Ser20 by cGMP-dependent protein kinase regulates spliceosome assembly. EMBO J. 1999;18:4549–4559. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.16.4549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Selenko P, Gregorovic G, Sprangers R, Stier G, Rhani Z, Kramer A, Sattler M. Structural basis for the molecular recognition between human splicing factors U2AF65 and SF1/mBBP. Mol Cell. 2003;11:965–976. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00115-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kielkopf CL, Lucke S, Green MR. U2AF homology motifs: protein recognition in the RRM world. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1513–1526. doi: 10.1101/gad.1206204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kielkopf CL, Rodionova NA, Green MR, Burley SK. A novel peptide recognition mode revealed by the X-ray structure of a core U2AF35/U2AF65 heterodimer. Cell. 2001;106:595–605. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00480-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bieche I, Manceau V, Curmi PA, Laurendeau I, Lachkar S, Leroy K, Vidaud D, Sobel A, Maucuer A. Quantitative RT-PCR reveals a ubiquitous but preferentially neural expression of the KIS gene in rat and human. Brain Res. Mol Brain Res. 2003;114:55–64. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(03)00132-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maucuer A, Ozon S, Manceau V, Gavet O, Lawler S, Curmi P, Sobel A. KIS is a protein kinase with an RNA recognition motif. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:23151–23156. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.37.23151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maucuer A, Camonis JH, Sobel A. Stathmin interaction with a putative kinase and coiled-coil-forming protein domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:3100–3104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maucuer A, Le Caer JP, Manceau V, Sobel A. Specific Ser-Pro phosphorylation by the RNA-recognition motif containing kinase KIS. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:4456–4464. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boehm M, Yoshimoto T, Crook MF, Nallamshetty S, True A, Nabel GJ, Nabel EG. A growth factor-dependent nuclear kinase phosphorylates p27(Kip1) and regulates cell cycle progression. EMBO J. 2002;21:3390–3401. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arning S, Gruter P, Bilbe G, Kramer A. Mammalian splicing factor SF1 is encoded by variant cDNAs and binds to RNA. RNA. 1996;2:794–810. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beausoleil SA, Jedrychowski M, Schwartz D, Elias JE, Villen J, Li J, Cohn MA, Cantley LC, Gygi SP. Large-scale characterization of HeLa cell nuclear phosphoproteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:12130–12135. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404720101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shu H, Chen S, Bi Q, Mumby M, Brekken DL. Identification of phosphoproteins and their phosphorylation sites in the WEHI-231 B lymphoma cell line. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2004;3:279–286. doi: 10.1074/mcp.D300003-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bennett M, Michaud S, Kingston J, Reed R. Protein components specifically associated with prespliceosome and spliceosome complexes. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1986–2000. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.10.1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peled-Zehavi H, Berglund JA, Rosbash M, Frankel AD. Recognition of RNA branch point sequences by the KH domain of splicing factor 1 (mammalian branch point binding protein) in a splicing factor complex. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:5232–5241. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.15.5232-5241.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zamore PD, Patton JG, Green MR. Cloning and domain structure of the mammalian splicing factor U2AF. Nature. 1992;355:609–614. doi: 10.1038/355609a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zamore PD, Green MR. Identification, purification, and biochemical characterization of U2 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein auxiliary factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:9243–9247. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.23.9243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shen H, Green MR. A pathway of sequential arginine-serine-rich domain-splicing signal interactions during mammalian spliceosome assembly. Mol Cell. 2004;16:363–373. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Valcarcel J, Gaur RK, Singh R, Green MR. Interaction of U2AF65 RS region with pre-mRNA branch point and promotion of base pairing with U2 snRNA [corrected] Science. 1996;273:1706–1709. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5282.1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang T, Vilardell J, Query CC. Pre-spliceosome formation in S.pombe requires a stable complex of SF1-U2AF(59)-U2AF(23) EMBO J. 2002;21:5516–5526. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abovich N, Liao XC, Rosbash M. The yeast MUD2 protein: an interaction with PRP11 defines a bridge between commitment complexes and U2 snRNP addition. Genes Dev. 1994;8:843–854. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.7.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rutz B, Seraphin B. Transient interaction of BBP/ScSF1 and Mud2 with the splicing machinery affects the kinetics of spliceosome assembly. RNA. 1999;5:819–831. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299982286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rain JC, Legrain P. In vivo commitment to splicing in yeast involves the nucleotide upstream from the branch site conserved sequence and the Mud2 protein. EMBO J. 1997;16:1759–1771. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.7.1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tanackovic G, Kramer A. Human splicing factor SF3a, but not SF1, is essential for pre-mRNA splicing in vivo. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:1366–1377. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-11-1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kramer A. Purification of splicing factor SF1, a heat-stable protein that functions in the assembly of a presplicing complex. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:4545–4552. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.10.4545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guth S, Valcarcel J. Kinetic role for mammalian SF1/BBP in spliceosome assembly and function after polypyrimidine tract recognition by U2AF. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:38059–38066. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001483200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Banerjee H, Rahn A, Gawande B, Guth S, Valcarcel J, Singh R. The conserved RNA recognition motif 3 of U2 snRNA auxiliary factor (U2AF 65) is essential in vivo but dispensable for activity in vitro. RNA. 2004;10:240–253. doi: 10.1261/rna.5153204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rutz B, Seraphin B. A dual role for BBP/ScSF1 in nuclear pre-mRNA retention and splicing. EMBO J. 2000;19:1873–1886. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.8.1873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang D, Paley AJ, Childs G. The transcriptional repressor ZFM1 interacts with and modulates the ability of EWS to activate transcription. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:18086–18091. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.29.18086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang D, Childs G. Human ZFM1 protein is a transcriptional repressor that interacts with the transcription activation domain of stage-specific activator protein. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:6868–6877. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.12.6868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Blanchette M, Labourier E, Green RE, Brenner SE, Rio DC. Genome-wide analysis reveals an unexpected function for the Drosophila splicing factor U2AF50 in the nuclear export of intronless mRNAs. Mol Cell. 2004;14:775–786. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gama-Carvalho M, Krauss RD, Chiang L, Valcarcel J, Green MR, Carmo-Fonseca M. Targeting of U2AF65 to sites of active splicing in the nucleus. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:975–987. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.5.975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lu KP, Liou YC, Zhou XZ. Pinning down proline-directed phosphorylation signaling. Trends Cell Biol. 2002;12:164–172. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)02253-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kramer A, Quentin M, Mulhauser F. Diverse modes of alternative splicing of human splicing factor SF1 deduced from the exon-intron structure of the gene. Gene. 1998;211:29–37. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00058-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu Z, Luyten I, Bottomley MJ, Messias AC, Houngninou-Molango S, Sprangers R, Zanier K, Kramer A, Sattler M. Structural basis for recognition of the intron branch site RNA by splicing factor 1. Science. 2001;294:1098–1102. doi: 10.1126/science.1064719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kramer A. Purification of splicing factor SF1, a heat-stable protein that functions in the assembly of a presplicing complex. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:4545–4552. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.10.4545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]