Abstract

The intergenic transcribed spacers (ITS) between the 16S and 23S rRNA genetic loci are frequently used in PCR fingerprinting to discriminate bacterial strains at the species and intraspecies levels. We investigated the molecular nature of polymorphisms in ITS-PCR fingerprinting of low-G+C-content spore-forming bacteria belonging to the genera Bacillus, Brevibacillus, Geobacillus, and Paenibacillus. We found that besides the polymorphisms in the homoduplex fragments amplified by PCR, heteroduplex products formed during PCR between amplicons from different ribosomal operons, with or without tRNA genes in the ITS, contribute to the interstrain variability in ITS-PCR fingerprinting patterns obtained in polyacrylamide-based gel matrices. The heteroduplex nature of the discriminating bands was demonstrated by fragment separation in denaturing polyacrylamide gels, by capillary electrophoresis, and by cloning, sequencing, and recombination of purified short and tRNA gene-containing long ITS. We also found that heteroduplex product formation is enhanced by increasing the number of PCR cycles. Homoduplex-heteroduplex polymorphisms (HHP) in a conserved region, such as the 16S and 23S rRNA gene ITS, allowed discrimination of closely related strains and species undistinguishable by other methods, indicating that ITS-HHP analysis is an easy and reproducible additional tool for strain typing.

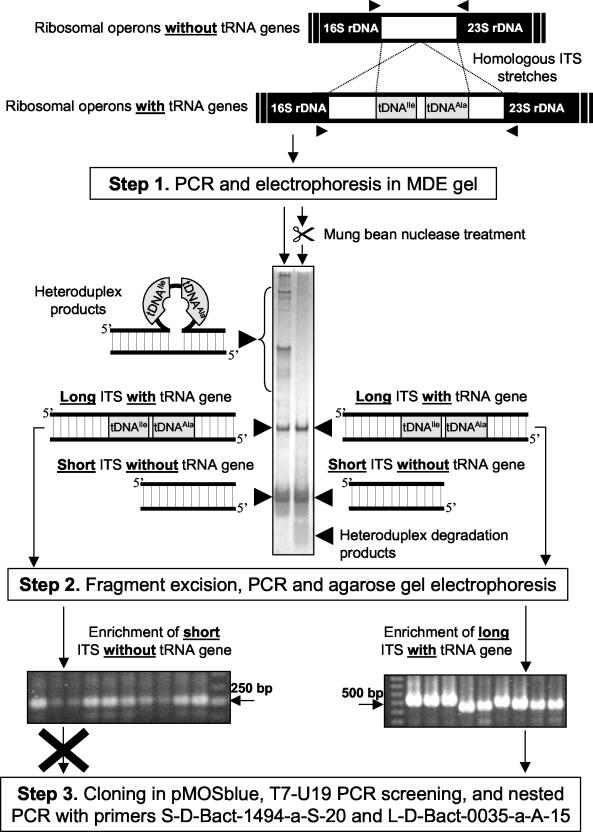

In the last 10 years intergenic transcribed spacers (ITS) between 16S and 23S rRNA genes have received a great deal of attention for strain typing, since such regions have greater polymorphism than adjacent genes (16, 20). Furthermore, because of the increasing number of ITS sequences that are being deposited in databases, a database specific for ITS, the Ribosomal Internal Spacer Sequence Collection, has been developed, in which 2,614 ITS sequences had been deposited as of the end of May 2003 (13). Polymorphism in ITS is quite often due to the presence of tRNA genes, since such genes are responsible for interoperonic and intrastrain length and sequence polymorphisms (14-16). This polymorphism can be used for discriminating closely related strains in species that harbor multiple ribosomal operons that differ in length and sequence (4, 18, 19). Recently, we used ITS-PCR typing in polyacrylamide-based gels to discriminate between closely related strains and species in the Bacillus cereus group (10). Many polymorphisms were found in slowly migrating bands. On the basis of the results of mung bean nuclease experiments it was hypothesized that slowly migrating polymorphic bands of strains were heteroduplex cross-hybridization products between ITS of different lengths due to the presence or absence of tRNA genes (7, 10). The homologous regions at the 3′ and 5′ ends of different ITS cross-hybridize to form heteroduplex DNA structures that have reduced electrophoretic mobilities compared with the mobilities of the corresponding homoduplex products depending on the amount of single-stranded DNA present in the heteroduplex product and the number of secondary structures formed within the single-stranded regions (Fig. 1) (7, 10, 18, 19). Mung bean nuclease cuts single strands in double-stranded products, eliminating heteroduplexes and releasing low-molecular-weight bands representing digestion products (7, 10). Such treatment of the ITS-PCR products of strains of the B. cereus group resulted in digestion of the slowly migrating bands in the gels and the disappearance of these bands from the profiles, leaving only homoduplex products (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Schematic diagram showing how heteroduplex cross-hybridization products may be formed during PCR and how these products may be eliminated from the pattern by mung bean nuclease treatment. Steps 1 to 3 show the procedure used to facilitate cloning of long ITS containing tRNA genes from B. anthracis strain 282. The two lanes in the silver-stained MDE gel show the ITS-HHP profile of strain 282 (left lane) and the same products after mung bean nuclease treatment (right lane). When a standard procedure consisting of excision of bands from the ITS-HHP profile and a PCR to generate a sufficient amount of DNA for cloning was used, short ITS without tRNA genes were always coamplified, which led to their preferential cloning. Band excision from a mung bean nuclease-treated profile completely eliminated heteroduplex forms, which facilitated exclusive recovery of the long ITS by PCR and successive cloning of this ITS.

In the present study our aim was to further investigate the nature of the strain-specific bands that allow strain discrimination in the ITS-PCR profile. We demonstrated the heteroduplex nature of the polymorphic bands by using several approaches, including a heteroduplex reconstruction experiment involving recombination of cloned short and long ITS. The suitability of this fingerprinting method, designated ITS homoduplex-heteroduplex polymorphism (ITS-HHP) analysis (10), for typing purposes was tested with other species belonging to four genera of the low-G+C-content, gram-positive, spore-forming bacteria (1), some of which are not easily discriminated on the basis of other fingerprinting analyses (5, 8, 9).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and ITS-HHP fingerprinting.

The strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Stock cultures of the strains were maintained at −80°C in liquid growth medium with 20% glycerol. Most strains were cultured in plate count broth or agar at 30°C; the exceptions were Bacillus licheniformis strains, which were incubated at 37°C, and the thermophilic strains Bacillus caldolyticus DSMZ 405, Bacillus caldotenax DSMZ 406, Bacillus caldovelox DSMZ 411, Bacillus flavothermus DSMZ 2641, Geobacillus thermocatenulatus DSMZ 730, Geobacillus thermodenitrificans DSMZ 465, Geobacillus thermoleovorans ATCC 43513T, and Geobacillus stearothermophilus ATCC 12016, ATCC 21365, ATCC 29609, ATCC 12980, and DSMZ 22T, which were grown at 55°C. Bacillus anthracis DNA was obtained from the Institute Pasteur, Paris, France.

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study

| Species (no. of strains) | Strains | Sourcea |

|---|---|---|

| Bacillus amyloliquefaciens (1) | DSMZ 7T | DSMZ |

| Bacillus anthracis (18) | 170, 227, 282, 300, 376, 582, 663, 779, 832, 846, 957, 4229, 6602, 7700, 7702, Cepanzo, Davis TE702 | IPP |

| ANTmi2522 | IZF | |

| Bacillus caldovelox (1) | DSMZ 411 | DSMZ |

| Bacillus caldolyticus (1) | DSMZ 405 | DSMZ |

| Bacillus caldotenax (1) | DSMZ 406 | DSMZ |

| Bacillus cereus (3) | DSMZ 31T, DSMZ 626, DSMZ 6127 | DSMZ |

| Bacillus coagulans (1) | DSMZ 1T | DSMZ |

| Bacillus flavothermus (1) | DSMZ 2641 | DSMZ |

| Bacillus licheniformis (7) | ATCC 14580T | ATCC |

| 3.2, 283, 75.2, 17.1, 6.1 | DISTAM | |

| DSMZ 13T | DSMZ | |

| Bacillus maroccanus (1) | CCM 671 | LMT |

| Bacillus megaterium (1) | DSMZ 32T | DSMZ |

| Bacillus mycoides (4) | G2, NOV1 | DISTAM |

| DSMZ 303, DSMZ 2048T | DSMZ | |

| Bacillus pacificus (1) | CCM 689 | LMT |

| Bacillus pseudomycoides (1) | NRRL 617T | NRRL |

| Bacillus smithii (1) | DSMZ 4216 | DSMZ |

| Bacillus sphaericus (2) | DSMZ 461, DSMZ 1087 | DSMZ |

| Bacillus subtilis (3) | 357, 42, 8633 | DISTAM |

| Bacillus thuringiensis (4) | HD1, DSMZ 2046T | DISTAM |

| DSMZ | ||

| BMG1.1, BMG1.7 | LMT | |

| Bacillus weihenstephanensis (1) | 10204T | WSBC |

| Brevibacillus brevis (1) | DSMZ 30T | DSMZ |

| Geobacillus stearothermophilus (5) | ATCC 12016, ATCC 12980, ATCC 21365, ATCC 29609 | ATCC |

| DSMZ 22T | DSMZ | |

| Geobacillus thermocatenulatus (1) | DSMZ 730 | DSMZ |

| Geobacillus thermodenitrificans (1) | DSMZ 465 | DSMZ |

| Geobacillus thermoleovorans (1) | ATCC 43513T | ATCC |

| Paenibacillus polymyxa (1) | DSMZ 36T | DSMZ |

| Bacillus sp. (2) | 1459, O1170 | LMT |

Institutions from which the strains were obtained: DISTAM, Dipartimento di Scienze e Tecnologie Alimentari e Microbiologiche, Milan, Italy; DSMZ, Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen GmbH, Braunschweig, Germany; IPP, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France. IZF, Istituto Zooprofilattico, Milan, Italy; LMT, Laboratoire de Microbiologie, Département de Biologie, Tunis, Tunisia; NRRL, Agricultural Research Service Culture Collection, Peoria, Ill.; WSBC, Weihenstephan Bacillus Collection, Weihenstephan, Germany; ATCC, American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va. Total DNA of the B. anthracis strains were kindly provided by M. Mock.

Total DNA was extracted from the washed cells by sodium dodecyl sulfate-proteinase-cethyltrimethyl ammonium bromide treatment as described by Ausubel et al. (2).

PCR amplification of 16S-23S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) ITS was performed as previously described (8-10). Briefly, reactions were carried out in 50-μl mixtures in an I-cycler (Bio-Rad, Milan, Italy) by using 1.25 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Milan, Italy), 5 μl of 10× Mg-free PCR buffer, each deoxynucleoside triphosphate at a concentration of 200 μM, 2.5 mM MgCl2, each primer at a concentration of 0.3 μM, and 2 μl of bacterial DNA. Primers S-D-Bact-1494-a-S-20 (5′-GTCGTAACAAGGTAGCCGTA-3′) and L-D-Bact-0035-a-A-15 (5′-CAAGGCATCCACCGT-3′) were used. The PCR cycling conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 94°C for 4 min, followed by 35 cycles consisting of 94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 7 min, and 72°C for 2 min, and a final extension step at 72°C for 7 min. To test the effect of the number of PCR cycles on the formation of heteroduplex products, different PCRs were carried out with some selected strains, and the number of cycles was varied from 25 to 40.

PCR products were separated in standard 2% agarose gels in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer (27) and in 6% polyacrylamide gels and 0.6× MDE gels (BioWhittaker Molecular Applications, Milan, Italy) in 1× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer under the conditions described previously (10). MDE is a separation matrix consisting of a particular polyacrylamide specifically designed to separate nucleic acid fragments on the basis of their secondary structures; nucleotide polymorphisms can be highlighted by differential migration due to differential single-strand or heteroduplex conformations. After electrophoresis the gels were stained with ethidium bromide (27) or by silver staining (3, 29).

Identification of slowly migrating bands in ITS-HHP fingerprints as ITS by Southern hybridization.

To evaluate whether both the homoduplex and the slowly migrating fragments were derived from amplification of the original ITS, the DNA fragments amplified from different B. anthracis strains were separated in a high-resolution polyacrylamide gel (160 by 200 by 0.75 mm) in a Protean II apparatus (Bio-Rad) by using 1× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer for 16 h at 80 V. After electrophoresis the DNA fragments in the gel were blotted overnight on positively charged nylon membranes (Boehringer Mannheim, Milan, Italy) by capillary transfer (27), fixed under UV light for 4 min, and hybridized overnight at 42°C in 50% formamide with the digoxigenin-labeled short ITS from B. anthracis strain Cepanzo. Two 15-min membrane washes were performed at 55°C in a 0.1× SSC solution (20× SSC is 3 M NaCl plus 300 mM sodium citrate, pH 7.0) containing 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate. Probe labeling by random priming, prehybridization, hybridization, washing, and detection were performed by using a DIG DNA labeling and detection kit (Boehringer Mannheim) and following the instructions of the supplier. To obtain a purified ITS fragment for use as a probe, the 250-bp fragment in the amplification pattern of B. anthracis Cepanzo was excised from the agarose gel with a QIA quick gel extraction kit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany) and cloned into the plasmid vector pMOSBlue, supplied in a pMOSBlue blunt-ended cloning kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), by using manufacturer's protocol. The cloned ITS was sequenced with the vector primers T7 and U19 by using an ABI Prism BigDye terminator v3.0 cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystem, Milan, Italy), and the DNA fragments were resolved with an ABI Prism 310 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystem) (7).

16S-23S rDNA ITS separation under denaturing conditions.

Separation of the ITS-PCR products under denaturing conditions was performed in a 6% polyacrylamide gel in the presence of 7 M urea and 40% (vol/vol) formamide (17, 27). ITS-PCR products were also analyzed by using an ABI Prism 310 capillary sequencer in an automated ribosomal intergenic spacer analysis (ARISA) (11). The ITS were amplified by using the same primers and conditions that were used for standard ITS amplification, except that primer S-D-Bact-1494-a-S-20 labeled at the 5′ end with the phosphoramidite dye 6-carboxyfluorescein (Applied Biosystem) was used. Aliquots (1 to 5 μl) of the PCR products were mixed with 1 μl of the 1,000-bp internal size standard (Applied Biosystem) labeled with the phosphoramidite dye 6-carboxyrhodamine, 20 μl of deionized formamide was added, and the mixture was denatured at 95°C for 5 min and cooled in an ice bath. The PCR products were then separated with an ABI Prism 310 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystem) by using a capillary (47 cm by 50 μm) filled with 4% performance-optimized polymer (Applied Biosystem). The samples were electrophoresed under standard ABI 310 denaturing electrophoresis conditions for 45 min at 60°C by using a 50-U threshold of fluorescence intensity. The data were analyzed by using the GeneScan 3.1 software program (Applied Biosystem). The analysis output was a series of peaks (an electropherogram), the sizes of which were estimated by comparison with the fragments of the internal size standard.

16S-23S rDNA ITS heteroduplex digestion by mung bean nuclease.

To eliminate DNA fragments with single-stranded regions from the ITS-HHP profile, the ITS-PCR products were treated with mung bean nuclease (Fig. 1). Fifty microliters of the ITS-HHP fingerprinting product was purified with a QIAquick column (Qiagen) and eluted with 80 μl of resuspension buffer (6 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 6 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM EDTA). Thirty-eight microliters of the eluted DNA solution was treated for 30 min at 30°C with 10 to 15 U of mung bean endonuclease (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) diluted 1/10 (vol/vol) just before use in the dilution buffer (10 mM sodium acetate [pH 5], 0.1 mM zinc acetate, 1 mM cysteine, 0.1% [vol/vol] TritonX-100, 50% [vol/vol] glycerol). The reaction was performed in a 50-μl (final volume) mixture containing 10 μl of 5× reaction buffer consisting of 150 mM sodium acetate (pH 5.0), 250 mM NaCl, 5 mM ZnCl2, and 25% glycerol. The reaction was stopped by adding 100 μl of a 0.2% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate-74 mM Tris-HCl (pH 9.5)-1.2 M LiCl solution, and the mung bean nuclease was removed by phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1, vol/vol/vol) treatment. The aqueous phase was extracted with 1 volume of diethyl ether, and the DNA was precipitated with ethanol and resuspended in 10 μl of Tris-EDTA (pH 7.5). The mung bean nuclease-treated sample was electrophoresed in an MDE gel and compared with an untreated sample, and the DNA bands were revealed by silver staining (Fig. 1).

Cloning of short and long tDNA-containing 16S-23S rDNA ITS and heteroduplex reconstruction experiment.

To confirm the identities of slowly migrating bands in the gels as heteroduplex products, a heteroduplex reconstruction experiment was performed with B. anthracis strain 282 by recombining the pure short and long tRNA gene-containing ITS. The first step of the reconstruction experiment was cloning of the two types of ITS. The short ITS of strain 282 was cloned as described above for the short ITS of strain Cepanzo. For the long ITS a specifically designed procedure was used (Fig. 1). PCR-amplified ITS from strain 282 DNA were digested with mung bean nuclease, and the resulting products were separated in an MDE gel as described above. The homoduplex fragments were excised from the gel by cutting them out with a sterile scalpel. Gel slices were transferred into a sterile tube containing 50 μl of elution buffer (0.5 M ammonium acetate, 10 mM Mg2+ acetate, 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0], 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate) and incubated at 37°C for 3 h. Samples were centrifuged for 1 min at 12,000 × g at room temperature. Forty microliters of the supernatant was transferred into a new tube, and 2 volumes of ethanol was added for precipitation. After centrifugation, the DNA was dried for 30 min at 30°C and resuspended in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0). Two microliters of this solution was used as template DNA for ITS-PCR reamplification by using the same forward and reverse primers (S-D-Bact-1494-a-S-20 for the 16S rDNA and L-D-Bact-0035-a-A-15 for the 23S rDNA, respectively) used for generation of the original ITS-HHP profile. After the purity of the PCR products was checked by agarose and MDE gel electrophoresis, the two homoduplex ITS of B. anthracis 282 were cloned in the pMOSblue vector (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) as described above. Inserts were screened for the correct size by PCR by using the T7 and U19 primers with the vector. The inserts from the clones selected were sequenced as previously described (7). The two clones selected, one containing the short ITS of strain 282 and one containing the long ITS of strain 282, were used for the heteroduplex reconstruction experiment. To amplify the original ITS fragments from the cloned products, avoiding coamplification of the E. coli ITS, a nested PCR approach was used. After the first PCR performed with primers T7 and U19, 1 μl of the reaction mixture was taken and used as the template for the nested reaction, which was carried out with primers S-D-Bact-1494-a-S-20 and L-D-Bact-0035-a-A-15, which were originally used to generate the ITS-HHP fingerprint. The conditions used for the nested PCR were the same as those used for the ITS-HHP PCR. The purity of the amplified clones was checked by MDE gel electrophoresis.

The second step of the heteroduplex reconstruction experiment involved performing an ITS-HHP PCR with a mixture of the short and long ITS obtained after cloning as the template. Five-microliter portions of the resulting amplified products were mixed and diluted 1:10, and 2 μl of the resulting mixture was subjected to PCR amplification by using standard ITS-HHP conditions. The amplified fragments were separated in an MDE gel and silver stained (3, 29).

RESULTS

ITS-PCR fingerprinting and hybridization assay.

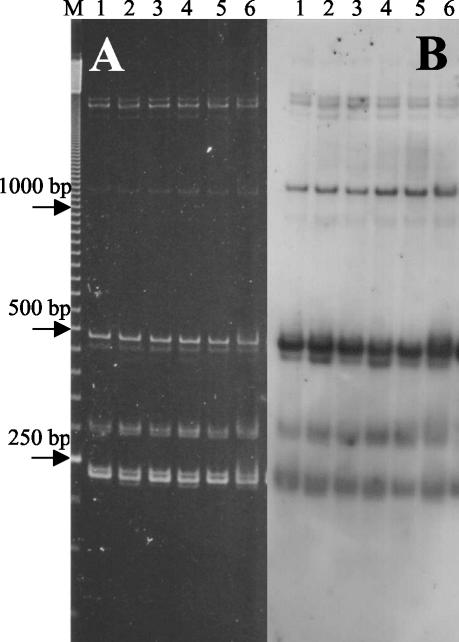

When ITS-PCR products are separated in electrophoretic matrices with higher resolution than agarose, slowly migrating bands can be identified (7, 10). Figure 2A shows the ITS-HHP profiles of several strains of B. anthracis after separation in a polyacrylamide gel. Several of the bands had very low migration rates and remained in the upper part of the gel at apparent positions above the position of the 1,000-bp standard. Since these bands have been shown to be important for discrimination of strains and species in the B. cereus group (10), a series of experiments were performed to understand their molecular nature. The first step was to verify that the products were indeed ITS and not nonspecific products of the PCR. The DNA in the gel shown in Fig. 2A was blotted onto a nylon membrane and hybridized with the digoxigenin-labeled ITS of B. anthracis strain Cepanzo (Fig. 2B). All the discrete bands present in the gel hybridized with the probe, showing that they were all true ITS.

FIG. 2.

ITS-PCR patterns of B. anthracis strains resolved by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (A) and by Southern hybridization with the short ITS cloned from B. anthracis strain Cepanzo as the probe (B). Lane M contained a 50-bp ladder. Lanes 1 to 6, B. anthracis strains 300, 376, 779, 832, 170, and 663, respectively. The position of the 250-bp band of the ladder is indicated on the left.

Nature of the slowly migrating bands.

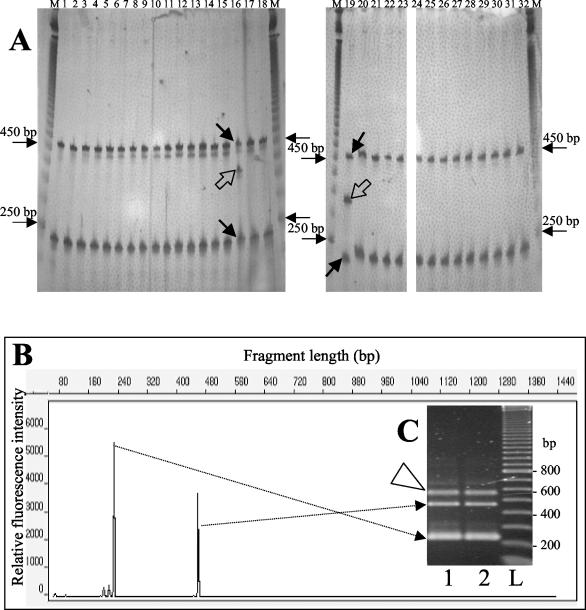

The MDE patterns were compared with patterns obtained after separation in denaturing gels; this separation precluded secondary structures, and the resulting bands represented only homoduplex products of different lengths. The ITS profiles in denaturing polyacrylamide gels showed much less variability between strains than the profiles in native polyacrylamide or MDE gels (Fig. 3A). In the case of the B. cereus group the strains produced only two bands (at about 240 and 470 bp), which was quite different from the results obtained under nondenaturing conditions, when up to 16 bands were evident (10), indicating that the upper bands in the native polyacrylamide and MDE gels were not homoduplex fragments. Two strains, B. anthracis Davis TE702 and Bacillus mycoides G2, produced additional bands at about 350 and 320 bp, and these bands represented intermediate ITS rather than heteroduplex products (7). ARISA with an ABI Prism 310 capillary sequencer in the Gene Scan mode confirmed the results obtained with the denaturing polyacrylamide gel. Figure 3B shows the ARISA profile for strain B. cereus DSMZ 31T as an example. Two main homoduplex peaks revealed by ARISA corresponded to fragments resolved in polyacrylamide gels under denaturing conditions.

FIG. 3.

ITS-PCR electrophoretic profiles of B. cereus group strains obtained under denaturing conditions. (A) Denaturing 6% polyacrylamide gels (denaturation with 40% formamide and 7 M urea). Lanes M contained a 50-bp ladder. Lanes 1 to 18, B. anthracis strains 282, 582, 846, 376, 663, 832, 779, 300, 170, 227, 957, Cepanzo, 6602, 4229, 7702, Davis TE702, 7700, and ANTmi2522, respectively; lanes 19 to 22, B. mycoides strains G2, DSMZ 2048T, DSMZ 303, and NOV1, respectively; lane 23, B. pseudomycoides strain NRRL 617T; lane 24, B. weihenestephanensis strain 10204T; lanes 25 to 27, B. cereus strains DSMZ 31T, DSMZ 626, and DSMZ 6127, respectively; lanes 28 to 32, B. thuringiensis strains DSMZ 2046T, HD1, BMG1.7, and BMG1.1, respectively. The solid arrows on the gel indicate the short and long ITS homoduplex PCR products, while the open arrow indicates homoduplex fragments of intermediate-length ITS present in strains Davis TE702 and G2. The positions of the 250- and 450-bp bands of the ladder are indicated on the left and on the right. (B) Electropherogram showing the ARISA profile of strain B. cereus DSMZ 31T. The dotted arrows connect the short and long ITS peaks of the ARISA profile with the corresponding ITS homoduplex products in the agarose gel in panel C. (C) Agarose gel electrophoresis of strain B. cereus DSMZ 31T (lanes 1 and 2). The open arrowhead indicates the position of the heteroduplex products. Lane L contained a 100-bp ladder. The positions of the 200-, 400-, 600-, and 800-bp bands of the ladder are indicated on the right.

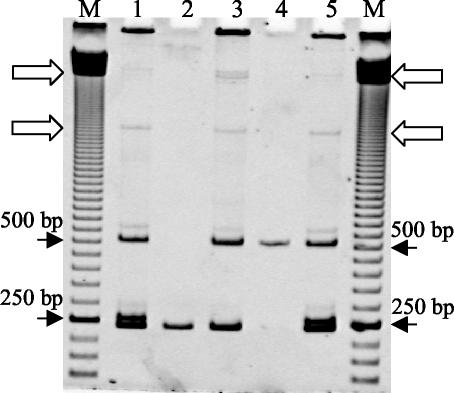

Heteroduplex reconstruction was performed by combining the PCR-amplified products of short and long tDNA-containing ITS cloned from B. anthracis strain 282 by using the procedure shown in Fig. 1. The PCR products obtained from each of the cloned ITS were mixed and used as the template for a PCR performed with the original ITS primers. Figure 4 compares the products of this PCR with the original ITS-HHP profile obtained for total DNA of strain 282. Amplification of the mixture of the cloned short and long tDNA-containing ITS produced the same bands in the upper part of the gel that were obtained by using the total DNA of strain 282 as the template, indicating that these bands were indeed heteroduplex products deriving from cross-hybridization of the short and long tDNA-containing ITS.

FIG. 4.

Silver-stained MDE gel showing ITS heteroduplex reconstruction by PCR amplification of the mixture of short and long tDNA-containing ITS clones of B. anthracis strain 282. Lanes M contained a 50-bp ladder. Lanes 1 and 5, ITS-PCR profile of strain B. anthracis 282; lane 2, PCR product of the short ITS obtained by nested PCR from clone ITS282.1; lane 4, PCR product of the long tRNA-containing ITS obtained by nested PCR from clone ITS282.6; lane 3, heteroduplex reconstruction obtained by PCR amplification of mixed clones ITS282.1 and ITS282.6. The open arrows indicate the positions of the heteroduplex products The positions of the 250- and 500-bp bands of the ladder are indicated on the left and on the right.

The influence of the number of PCR cycles on the complexity of the ITS-HHP pattern was evaluated by using the DNA from several strains. Figure 5 shows how varying the number of cycles from 25 to 40 affected the complexity of the fingerprint. The experiment was conducted with six unrelated strains showing different complexities in their ITS-HHP profiles. When more than 30 cycles were used, there were clearly detectable heteroduplex fragments that could be detected by both agarose and MDE gel electrophoresis.

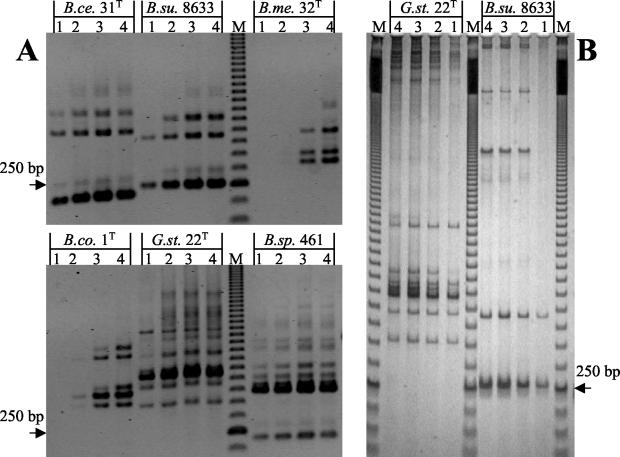

FIG. 5.

Effect of the number of cycles of the PCR on the formation of heteroduplex products. Lanes 1 to 4 show the ITS-PCR patterns obtained after 25, 30, 35, and 40 cycles, respectively. The strains used were Bacillus cereus DSMZ 31T (B.ce. 31T), Bacillus subtilis 8633 (B.su. 8633), Bacillus megaterium DSMZ 32T (B.me. 32T), Bacillus coagulans DSMZ 1T (B.co. 1T), Geobacillus stearothermophilus DSMZ 22T (G.st. 22T), and Bacillus sphaericus DSMZ 461 (B.sp. 461). (A) Negative images of agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide. (B) Silver-stained MDE gel.

ITS-PCR fingerprinting of the genus Bacillus and related genera.

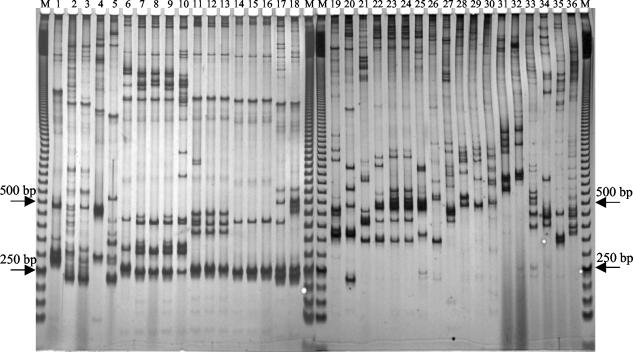

To evaluate the feasibility of ITS-HHP analysis of species of the genus Bacillus and related genera (1), we analyzed a total of 65 strains belonging to 25 species of the genera Bacillus, Brevibacillus, Geobacillus, and Paenibacillus. Figure 6 shows examples of the ITS-HHP profiles obtained. All of the strains gave reproducible patterns. According to previous results (10), among 18 strains of B. anthracis three patterns were found which could be discriminated from the other patterns obtained for the species belonging to the B. cereus group. B. licheniformis strains were similar to Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens but could be distinguished from these species by additional bands in the 300- to 500-bp range or in the upper part of the gel. Among the seven B. licheniformis strains five pattern types were found; one type included strains 3.2 and 75.2, one type included the two type strains from the American Type Culture Collection and the Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen, and the other three types each contained one of the three remaining strains (6.1, 17.1, and 283). The three strains of B. subtilis gave identical patterns. The other species of 16S rRNA group I produced typical fingerprints, like the species of the other rRNA groups. In general, ITS-HHP analysis discriminated all these species much more clearly than agarose gel analysis discriminated them (8).

FIG. 6.

ITS-HHP pattern variability observed in the collection examined. Lanes M contained a 50-bp ladder. Lanes 1 to 6, Bacillus maroccanus CCM 671, Bacillus pacificus CCM 689, Bacillus sphaericus DSMZ 1087, Bacillus sphaericus DSMZ 461, Bacillus smithii DSMZ 4216, and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens DSMZ 7T, respectively; lanes 7 to 13, Bacillus licheniformis strains 3.2, 283, 75.2, 17.1, 6.1, ATCC 14580T, and DSMZ 13T, respectively; lanes 14 to 16, Bacillus subtilis strains 357, 42, and 8633, respectively; lanes 17 and 18, Bacillus anthracis strains Davis TE702 and 7700, respectively; lane 19, Geobacillus thermocatenulatus DSMZ 730; lanes 20 to 24, Geobacillus stearothermophilus strains ATCC 12016, ATCC 21365, ATCC 29609, ATCC 12980, and DSMZ 22T, respectively; lanes 25 to 36, Geobacillus thermodenitrificans DSMZ 465, Bacillus caldovelox DSMZ 411, Bacillus flavothermus DSMZ 2641, Geobacillus thermoleovorans ATCC 43513T, Bacillus caldolyticus DSMZ 405, Bacillus caldotenax DSMZ 406, Bacillus sp. strain OI170, Bacillus sp. strain 1459, Paenibacillus polymyxa DSMZ 36T, Bacillus coagulans DSMZ 1T, Bacillus megaterium DSMZ 32T, and Brevibacillus brevis DSMZ 30T, respectively. The positions of the 250- and 500-bp bands of the ladder are indicated on the left and on the right.

In the case of the Geobacillus and thermophilic Bacillus strains, ITS-HHP analysis revealed a marked degree of variability, not only among the different species themselves but also among strains belonging to the same taxon, identified on the basis of previous observations (23). Four different ITS-HHP fingerprints were detected among five G. stearothermophilus strains. Strain ATCC 12980T and the equivalent strain DSMZ 22T produced identical electrophoretic profiles that were characterized by main amplified fragments at about 350, 420, and 500 bp. Strain ATCC 29609 produced a profile similar to that of the type strains; the main difference was an additional band at 700 bp. Strains ATCC 12016 and ATCC 21365 were characterized by typical profiles with amplified fragments at 260, 370, 490, 560, and 700 bp and at 350, 400, and 620 bp, respectively, and by additional fragments at apparent positions above the position of the 1,000-bp standard. Furthermore, G. thermocatenulatus DSMZ 730, G. thermoleovorans ATCC 43513T, and the closely related organisms Bacillus caldovelox, B. caldolyticus, and B. caldotenax produced strain-specific ITS-HHP profiles, in accordance with the ITS amplification profiles analyzed in standard agarose gels (23).

For several species and strains, specific signature fragments were found among the heteroduplex products in the upper parts of the gels (10, 18). For example, in the case of the B. subtilis strains, two slowly migrating bands (Fig. 6) clearly distinguished specific fragments from the related species B. amyloliquefaciens and B. licheniformis.

DISCUSSION

PCR amplification with primers at the 3′ end of 16S rDNA and at the 5′ end of 23S rDNA facing outside the corresponding genes results in amplification of the ITS, the intergenic region between the 16S and 23S rDNA. The spore-forming bacteria belonging to the genus Bacillus and related genera can harbor multiple ribosomal operons in their genomes (21, 26). In B. cereus and related species there are up to 12 ribosomal operons (21). Since the lengths of the ITS in the different operons can differ, PCR amplification generates a band pattern that, at the species level, appears to be typical. For example, amplifying the ITS of the species belonging to the B. cereus group results in three bands in agarose gels (10). Increasing the resolution power of electrophoresis by using polyacrylamide-based separation matrices in ITS-HHP analysis increases the number of bands and generates more complex patterns with slowly migrating bands that are strain specific and suitable for strain typing.

Southern hybridization of ITS-HHP profiles in polyacrylamide gels confirmed that all the bands in the patterns, including slowly migrating bands, were true ITS. B. cereus and its relatives have been shown to have a ribosomal operon organization similar to that of B. subtilis (22) that includes two types of ribosomal operons with respect to ITS (7). Among the types of ITS found in the species of the B. cereus group the longest is 371 bp long (7). Hence, the slowly migrating bands observed when PCR-amplified ITS were separated in polyacrylamide-based gels were thought to be artificial ITS-based fragments that were generated during the PCR. These fragments could have been heteroduplex products that were generated by cross-hybridization of the short and long tDNA-containing ITS. Due to different shapes the heteroduplex molecules migrated in the gel at a lower rate than normal homoduplex fragments migrated.

The heteroduplex nature of the slowly migrating bands was demonstrated by mung bean nuclease digestion, which was used to cut single strands in double-stranded products, eliminating heteroduplex products and releasing low-molecular-weight bands representing digestion products (7, 10) (Fig. 1). Such treatment of the ITS-PCR products of strains belonging to the B. cereus group resulted in digestion of the slowly migrating bands in the gels and disappearance of these bands from the profile, leaving only homoduplex products.

Separation of ITS (including the 16S and 23S rDNA stretches) under denaturing conditions both by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and by capillary electrophoresis showed that the amplifiable ITS in the species belonging to the B. cereus group are not more than 500 bp long. In fact, this kind of analysis showed that in two strains, B. anthracis Davis TE702 and B. mycoides G2, other types of ITS are present, but they are ITS whose lengths are intermediate between the lengths of ITS without tRNA genes and the lengths of ITS with tRNAIle and tRNAAla genes. Sequencing of these two fragments showed that the 350-bp fragment of strain Davis TE702 was an ITS containing a single tRNA gene, while the 320-bp fragment of strain G2 did not contain any tRNA gene and did not show significant homology with any known sequence in the database (7). These experiments demonstrated that when ITS amplified products are electrophoresed in native gels, not all the bands represent homoduplex products. Moreover, we found that in the B. cereus group, ITS analysis based solely on PCR product length does not result in easy discrimination of species or strains.

To further demonstrate the nature of slowly migrating bands in ITS-HHP profiles as heteroduplex products between short and long ITS containing tRNA genes, we performed heteroduplex reconstruction experiments in which we mixed and amplified the two different ITS (the short ITS and the long tRNA gene-containing ITS) from B. anthracis strain 282 after they were isolated by cloning. All the attempts that we made to clone the long ITS from the original PCR products or after the corresponding band was excised from agarose, polyacrylamide, and MDE gels failed since only the short ITS was found in the plasmid insert when we screened E. coli colonies. We concluded that the short ITS competes with the longer ITS for the ligase reaction and is therefore preferentially cloned. Also, Nagpal et al. (24) had similar problems with cloning tDNA-containing ITS of B. subtilis. To overcome the preferential cloning of short homoduplex fragments in favor of the longer fragments, we used the procedure shown in Fig. 1, in which the heteroduplex fragments were eliminated from the PCR product mixture by mung bean nuclease treatment. Following separation in an MDE gel it was possible to excise from the gel the pure homoduplex band representing the ITS containing tRNA genes. Hence, the purified fragment could be easily cloned. By mixing the cloned short and long ITS it was possible to reconstruct the heteroduplex fragments which are typically found in ITS-HHP profiles of strains with multiple operons that differ in length due to tDNA.

Considering the discriminative power of heteroduplexes, the levels of these cross-hybridization products need to be increased to the maximum possible value in strain-typing studies by using the ITS as the target region. Thus, there are several requirements. One requirement is the use of a high number of PCR cycles (18, 19). Figure 6 clearly shows that the production of slowly migrating bands which help in strain discrimination depends on the number of cycles used for the PCR. As the cycle number increases during the PCR and the concentration of the newly synthesized fragments increases, the efficiency of the reaction decreases because a plateau is reached, during which formation of new products is not allowed due to inactivation of the DNA polymerase or limitations in one or more substrates of the reaction. As a consequence, during the final PCR cycles the homoduplex fragments generated during the first cycles are continuously denatured and renatured, allowing formation of imperfect pairs of ITS fragments which have homologous DNA stretches. These hybrid double-stranded molecules are heteroduplexes that have a very low migration rate during electrophoresis. The formation of such hybrid molecules is hence enhanced by an increase in the number of PCR cycles. A second requirement for increasing the discriminative power of ITS-PCR analysis concerns the use of suitable separation matrices. MDE is an improved matrix compared to polyacrylamide. In fact, MDE is designed specifically to separate DNA fragments basing on different secondary structures, as is the case with heteroduplex products, and the use of MDE rather than standard polyacrylamide for ITS-PCR analysis is recommended.

We showed the effectiveness of ITS-HHP analysis for typing strains of aerobic low-G+C-content sporeformers (1) by analyzing 65 representative strains of 25 species belonging to four genera. These strains were representative of a wide phylogenetic range of the aerobic low-G+C-content sporeformers and together with another 114 strains of the six species belonging to the B. cereus group assayed by ITS-HHP analysis in a previous study (10) demonstrated the potential of ITS-HHP for resolving the diversity of strains and closely related species. Some of the strains were chosen to compare the effectiveness of discrimination by ITS-HHP analysis compared to that of other typing methods, like ITS-PCR (8, 9), tDNA-PCR (5, 9), random amplified polymorphic DNA fingerprinting (9), and repetitive element polymorphism-PCR (rep-PCR) fingerprinting with the BOX-A1R primer (6).

ITS-HHP analysis was able to identify 73 pattern types for a collection of 141 strains of the six species belonging to the B. cereus group (10) that, when analyzed by ITS-PCR and agarose gel electrophoresis, produced the same pattern type (8). By using ITS-HHP analysis B. anthracis strains were differentiated from strains of the other Bacillus species, and despite the clonal nature of B. anthracis three different types of patterns were found among 27 strains (10). For B. anthracis strains isolated during outbreaks that occurred in France, ITS-HHP analysis discriminated two main groups based on an eight-locus variable-number tandem repeat analysis performed with a collection of 50 B. anthracis isolates (12). The ITS-HHP analysis discriminated all the strains isolated from the south of France in the Pyrenees and Alps in the recent outbreaks that occurred in 1994 and 1997, supporting the hypothesis that there were at least two independent introductions of B. anthracis in France. These results are in agreement with those of Fouet et al. (12), who found that the strains isolated in the south of France and in the Pyrenees and Alps belong to a specific MLVA type, although a careful comparison with these strains could not be made since the strain desigantions were not reported by these authors (12).

A total of 112 of the 141 B. cereus group strains analyzed in this study and previously (10) by ITS-HHP analysis were also analyzed by rep-PCR fingerprinting with the BOX-A1R primer (6). rep-PCR yielded a higher number of fingerprint types (97 types for 112 strains) than ITS-HHP fingerprinting yielded (73 pattern types for 141 strains), but the genetic relationships obtained from the data obtained by the two fingerprinting methods resulted in similar tree topologies. Considering that ITS-HHP analysis targets a single known conserved locus compared to rep-PCR, ITS-HHP analysis has a relatively high level of strain discrimination due to the heteroduplexes formed between different ribosomal operons in the genome.

The effectiveness of ITS-HHP analysis compared to the effectiveness of other typing methods for strain discrimination was also observed with other species. Five ITS-HHP pattern types were found among the seven B. licheniformis strains analyzed in this study. The same strains yielded only three, four, and four patterns when they were analyzed by tDNA-PCR fingerprinting, ITS-PCR fingerprinting in an agarose gel, and random amplified polymorphic DNA fingerprinting with a single primer, respectively (9). In the case of the five strains of G. stearothermophilus, ITS-HHP analysis yielded four different profiles, like tDNA-PCR fingerprinting (5). These results confirmed the wide genetic diversity in G. stearothermophilus determined previously by DNA-DNA relatedness values (23). ITS-HHP analysis confirmed the distinctness of B. caldovelox, B. caldolyticus, and B. caldotenax, whose taxonomic position remains unclear and requires further revision. Chemotaxonomy and phylogenetic data indicate that these species belong to the genus Geobacillus (25); moreover, it has been suggested by Sunna et al. (28) and Mora et al. (23) that B. caldovelox, B. caldolyticus, B. caldotenax, and G. thermoleovorans ATCC 43513T belong to the same species. For the 500- to 900-bp range the ITS-HHP profiles revealed that these four organisms produce some common bands, further corroborating their similarity.

ITS-HHP analysis is a simple and rapid tool for typing strains of Bacillus and related genera. Apart from the simple separation of the PCR product in a suitable matrix, no further manipulation is required. Homoduplex (length) polymorphism and, especially, heteroduplex (sequence) polymorphism are powerful features for strain discrimination and typing when this method is used.

Acknowledgments

Support was provided by the Italian Ministry for University and Scientific Research within the project “Risposta della comunità microbica del suolo a differenti pressioni antropiche: effetti su struttura, dinamica e diversità della microflora” (Cofin 2000) and by the INTAS-International Association for the Promotion of Co-operation with Scientists from the New Independent States of the former Soviet Union within the project “An epidemiological study of outbreaks of B. anthracis in Georgia” (INTAS-01-0725). A.C. was supported by a grant from the Direction Generale de Recherche Scientifique et Technologique of the Ministere de l'Education Superieure of Tunisia.

We thank M. Mock for kindly giving us the total DNA of B. anthracis strains, C. Parini for providing the B. licheniformis strains, L. K. Nakamura for providing the Bacillus pseudomycoides strains, and S. Scherer for providing the strains of Bacillus weihenestephanensis. The manuscript was edited by Barbara Carey.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ash, C., J. A. E. Farrow, S. Wallbanks, and M. D. Collins. 1991. Phylogenetic heterogeneity of the genus Bacillus revealed by comparative analysis of small-subunit-ribosomal RNA sequences. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 13:202-206. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl. 1994. Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley and Sons, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 3.Bassam, B. J., G. Caetano-Anolles, and P. M. Gresshoff. 1991. Fast and sensitive silver staining of DNA in polyacrylamide gels. Anal. Biochem. 80:81-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baudart, J., K. Lemarchand, A. Brisabois, and P. Lebaron. 2000. Diversity of Salmonella strains isolated from the aquatic environment as determined by serotyping and amplification of the ribosomal DNA spacer regions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:1544-1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borin, S., D. Daffonchio, and C. Sorlini. 1997. Single strand conformation polymorphism analysis of PCR-tDNA fingerprinting to address the identification of Bacillus species. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 157:87-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cherif, A., L. Brusetti, S. Borin, A. Rizzi, A. Boudabous, H. Khyami-Horani, and D. Daffonchio. 2003. Genetic relationship in the ′Bacillus cereus group' by rep-PCR fingerprinting and sequencing of a Bacillus anthracis-specific rep-PCR fragment. J. Appl. Microbiol. 94:1108-1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cherif, A., S. Borin, A. Rizzi, H. Ouzari, A. Boudabous, and D. Daffonchio. 2003. Bacillus anthracis diverges from related clades of the Bacillus cereus group in 16S-23S rDNA internal transcribed spacers containing tRNA genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:33-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daffonchio, D., S. Borin, A. Consolandi, D. Mora, P. L. Manachini, and C. Sorlini. 1998. 16S-23S rRNA internal transcribed spacers as molecular markers for the species of the 16S rRNA group I of the genus Bacillus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 163:229-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daffonchio, D., S. Borin, G. Frova, P. L. Manachini, and C. Sorlini. 1998. PCR fingerprinting of whole genomes, of the spacers between the 16S and 23S rRNA genes and of intergenic tRNA gene regions reveals a different intraspecific genomic variability of Bacillus cereus and Bacillus licheniformis. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 48:107-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daffonchio, D., A. Cherif, and S. Borin. 2000. Homoduplex and heteroduplex polymorphisms of the amplified ribosomal 16S-23S internal transcribed spacers describe genetic relationships in the “Bacillus cereus group.” Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:5460-5468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisher, M. M., and E. W. Triplett. 1999. Automated approach for ribosomal intergenic spacer analysis of microbial diversity and its application to freshwater bacterial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:4630-4636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fouet, A., K. L. Smith, C. Keys, J. Vaissaire, C. Le Doujet, M. Lévy, M. Mock, and P. Keim. 2002. Diversity among French Bacillus anthracis isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:4732-4734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcia-Martinez, J., I. Bescos, J. J. Rodriguez-Sala, and F. Rodriguez-Valera. 2001. RISSC: a novel database for ribosomal 16S-23S RNA genes spacer regions. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:178-180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gürtler, V. 1999. The role of recombination and mutation in 16S-23S rDNA spacer rearrangement. Gene 238:241-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gürtler, V., Y. Rao, S. R. Pearson, S. M. Bates, and B. C. Mayall. 1999. DNA sequence heterogeneicity in three copies of the long 16S-23S rDNA spacer of Enterococcus faecalis isolates. Microbiology 145:1785-1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gürtler, V., and V. A. Stanisich. 1996. New approaches to typing and identification of bacteria using the 16S-23S rDNA spacer region. Microbiology 142:3-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iteman, I., R. Rippka, N. Tandeau de Marsac, and M. Herdman. 2000. Comparison of conserved structural and regulatory domains within divergent 16S rRNA-23S rRNA spacer sequences of cyanobacteria. Microbiology 146:1275-1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jensen, M. A., and R. J. Hubner. 1996. Use of homoduplex ribosomal DNA spacer amplification products and heteroduplex cross-hybridization products in the identification of Salmonella serovars. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:2741-2746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jensen, M. A., and N. Straus. 1993. Effect of PCR conditions on the formation of heteroduplex and single-stranded DNA products in the amplification of bacterial ribosomal DNA spacer regions. PCR Methods Applic. 3:186-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jensen, M. A., J. A. Webster, and N. Straus. 1993. Rapid identification of bacteria on the basis of polymerase chain reaction-amplified ribosomal DNA polymorphism. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:945-952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johansen, T., C. R. Carlson, and A.-B. Kolstø. 1996. Variable numbers of rRNA operons in Bacillus cereus strains. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 136:325-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kunst, F., N. Ogasawara, I. Moszer, A. M. Albertini, G. Alloni, V. Azevedo, M. G. Bertero, P. Bessieres, A. Bolotin, S. Borchert, R. Borriss, L. Boursier, A. Brans, M. Braun, S. C. Brignell, S. Bron, S. Brouillet, C. V. Bruschi, B. Caldwell, V. Capuano, N. M. Carter, S. K. Choi, J. J. Codani, I. F. Connerton, and A. Danchin. 1997. The complete genome sequence of the gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Nature 390:249-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mora, D., M. G. Fortina, G. Nicastro, C. Parini, and P. L. Manachini. 1998. Genotypic characterization of thermophilic bacilli: a study on new soil isolates and several reference strains. Res. Microbiol. 149:711-722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagpal, M. L., K. F. Fox, and A. Fox. 1998. Utility of 16S-23S rRNA spacer region methodology: how similar are interspace regions within a genome and between strains for closely related organisms? J. Microbiol. Methods 33:211-219. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nazina, T. N., T. P. Tourova, A. B. Poltaraus, E. V. Novikova, A. A. Grigoryan, A. E. Ivanova, A. M. Lysenko, V. V. Petrunyaka, G. A. Osipov, S. S. Belyaev, and M. V. Ivanov. 2001. Taxonomic study of aerobic thermophilic bacilli: descriptions of Geobacillus subterraneus gen. nov., and Geobacillus uzenensis sp. nov. from petroleum reservoirs and transfer of Bacillus stearothermophilus, Bacillus thermocatenulatus, Bacillus thermoleovorans, Bacillus kaustophilus, Bacillus thermoglucosidasius and Bacillus thermodenitrificans to Geobacillus as the new combinations G. stearothermophilus, G. thermocatenulatus, G. thermoleovorans, G. kaustophilus, G. thermoglucosidasius and G. thermodenitrificans. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 51:433-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nubel, U., B. Engelen, A. Felske, J. Snaidr, A. Wieshuber, R. I. Amann, W. Ludwig, and H. Backhaus. 1996. Sequence heterogeneities of genes encoding 16S rRNAs in Paenibacillus polymyxa detected by temperature gradient gel electrophoresis. J. Bacteriol. 178:5636-5643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 28.Sunna, A., S. Tokajian, J. Burghardt, F. Rainey, G. Antranikian, and F. Hashwa. 1997. Identification of Bacillus kaustophilus, Bacillus thermocatenulatus and Bacillus strain HSR as members of Bacillus thermoleovorans. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 20:232-237. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Viti, C., D. Forni, S. Ventura, A. Messini, R. Materassi, and L. Giovannetti. 2000. Characterisation and typing of Saccharomyces strains by DNA fingerprinting. Ann. Microbiol. 50:191-203. [Google Scholar]