Abstract

This is the first report of filamentous actinobacteria isolated from surface-sterilized root tissues of healthy wheat plants (Triticum aestivum L.). Wheat roots from a range of sites across South Australia were used as the source material for the isolation of the endophytic actinobacteria. Roots were surface-sterilized by using ethanol and sodium hypochlorite prior to the isolation of the actinobacteria. Forty-nine of these isolates were identified by using 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) sequencing and found to belong to a small group of actinobacterial genera including Streptomyces, Microbispora, Micromonospora, and Nocardiodes spp. Many of the Streptomyces spp. were found to be similar, on the basis of their 16S rDNA gene sequence, to Streptomyces spp. that had been isolated from potato scabs. In particular, several isolates exhibited high 16S rDNA gene sequence homology to Streptomyces caviscabies and S. setonii. None of these isolates, nor the S. caviscabies and S. setonii type strains, were found to carry the nec1 pathogenicity-associated gene or to produce the toxin thaxtomin, indicating that they were nonpathogenic. These isolates were recovered from healthy plants over a range of geographically and temporally isolated sampling events and constitute an important plant-microbe interaction.

The actinobacteria have been well characterized in the literature due to their economic importance as producers of two-thirds of the microbially derived antibiotics known today (6, 23). The actinobacteria are characterized by their gram-positive nature and high guanine-plus-cytosine (G+C) content in their genomes. Ecologically, actinobacteria and, particularly, the Streptomyces spp. are generally saprophytic, soil-dwelling organisms that spend the majority of their life cycles as semidormant spores (27). It has also been demonstrated that actinobacteria inhabit the rhizosphere of many plant species, including cereal crops such as wheat (13, 15, 30, 37).

Some actinobacteria are also known to form more intimate associations with plants and colonize their internal tissues. Within the order Actinomycetales there are examples of both endophytic and plant-pathogenic species. The best-characterized examples of the plant-pathogenic actinobacteria are the potato scab-causing Streptomyces scabies, S. acidiscabies, and S. turgidiscabies. Pathogenicity has been associated with the presence of a conserved and transmissible pathogenicity island (PAI) in their genomes (9, 21). This PAI encodes for the biosynthesis of a phytotoxin, thaxtomin, and also contains plant virulence factor genes such as nec1 (8, 22, 26). Actinorhizae (Frankia spp.) have been extensively researched as an endophytic association between a plant and an actinobacterium (for reviews, see references 3, 4, and 5). However, examples of actinobacteria other than Frankia inhabiting the root tissues of healthy plants as endophytes are rare. Sardi et al. (35) reported the presence of actinobacteria in root samples of crops and Italian native plants, with the majority of the isolates belonging to the genus Streptomyces. de Araujo et al. (14) found that actinobacteria could be isolated from the roots and leaves of maize (Zea mays L.), with the most commonly isolated genus being Microbispora, although Streptomyces and Streptosporangium spp. were also represented. Okazaki et al. (33) were also able to isolate Microbispora spp. at a much higher frequency from plant leaves than from the soil.

The present study is the first report of the isolation and identification of endophytic actinobacteria from healthy wheat plants. This work is part of a larger study that has characterized the actinobacterial endoflora of cereal plants and assessed their role in pathogen defense and growth regulation of their hosts. These beneficial activities are not the subject of the study presented here but are described in detail elsewhere (12).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sampling of wheat plants.

Nine fields from three major wheat-growing regions of South Australia were sampled over a growing season (May to November) at 6- to 7-week intervals. The Eyre Peninsula sites were characterized by sandy alkaline soils and relatively low rainfall (average, 330 mm year−1). The wheat fields sampled regularly in the South East region were characterized by cracking clay soils and higher rainfall (average, 600 mm year−1). The “Mid-North” area sites were characterized by loamy-earth soil (average rainfall, 500 mm year−1). At each sampling event, a total of 25 plants were dug out carefully to ensure that maximal amounts of root material were collected. These consisted of five batches of five plants taken at 5-m intervals in a line perpendicular to the fence line of the field. In the second year of sampling, plants were also collected over the growing season from a range of sites in the South East and Eyre Peninsula regions of South Australia.

Isolation of endophytic actinobacteria from wheat root tissue.

The plants were air dried for 48 h before being thoroughly washed to remove all soil from the root mass. Washing included a sonication step to dislodge any soil and organic matter from the roots. The roots were excised and subjected to a three-step surface sterilization procedure: a 60-s wash in 99% ethanol, followed by a 6-min wash in 3.125% NaOCl, a 30-s wash in 99% ethanol, and a final rinse in sterile reverse osmosis-treated (RO) water. The surface-sterilized roots were then aseptically sectioned into 1-cm fragments and distributed onto the isolation media, followed by incubation at 27°C for up to 4 weeks. Several isolation media were developed for the isolation of endophytic actinobacteria and used throughout the experiment. For each plant, root fragments were plated onto three media. All plant fragments were plated onto tap water-yeast extract agar (TWYE [13]; containing 0.25 g of yeast extract [Oxoid], 0.5 g of K2HPO4, and 18 g of agar [Oxoid] per liter of tap water) or humic acid-vitamin B agar (HV) (19); the third medium was either flour-yeast extract-sucrose-casein hydrolysate agar (containing 6 g of plain flour, 0.3 g of yeast extract [Oxoid], 0.3 g of sucrose, 0.3 g of CaCO3, and 18 g of agar [Oxoid] per liter of RO water), flour-calcium carbonate agar (containing 4 g of plain flour, 0.4 g of CaCO3, and 16 g of agar [Oxoid] per liter of RO water), or yeast extract-casein hydrolysate agar (YECD; containing 0.3 g of yeast extract [Oxoid], 0.3 g of d-glucose, 2 g of K2HPO4, and 18 g of agar [Oxoid] per liter of RO water). Benomyl (DuPont) was added to all of the agar media at 50 μg ml−1 to control (endophytic) fungal growth. The efficacy of the surface sterilization procedure was assessed by aseptically rolling surface-sterilized plant tissue onto each of the isolation media and tryptic soy agar (Oxoid) and then incubating it at 27°C. Growth of microorganisms, predominantly bacteria, on these plates indicated that the surface sterilization was inadequate. This occurred rarely (<5%) and may have been due to inadequate removal of soil particles. Isolation of endophytic actinobacteria was only carried out from roots in which sterilization was achieved.

Validation of the surface sterilization protocol.

The surface sterilization protocol has been used extensively for the isolation of endophytic fungi (7). Nevertheless, further control experiments were carried out to validate the sterilization procedure. This was done by using two methods with five replicates for each. Spore suspensions of five individual actinobacterial endophytes from the present study and two endophytic pseudomonads, from 107 to 109 CFU ml−1, were subjected to the three-step sterilization protocol of 99% ethanol for 1 min, 3.125% hypochlorite for 6 min, and 99% ethanol for 30 s. This was done in Eppendorf tubes with the solutions removed at each step by centrifugation. The untreated and treated spore suspensions were diluted and plated out onto potato dextrose agar (Oxoid), and the viable colonies were counted.

In the second method, the five actinobacterial species and two endophytic pseudomonads were coated onto surface-sterilized wheat seeds to give a count of between 106 to 108 CFU g of seeds−1, and the seeds were allowed to air dry for 48 h. The coated seeds were subjected to (i) washing four times with sterile water to simulate the sterilization steps and (ii) the aforementioned surface sterilization procedure. Treated and untreated seeds were then rolled on the surface of potato dextrose agar plates, and the plates were incubated.

Isolation of endophytic actinobacteria from wheat seed cv. Excalibur.

A method for the isolation of endophytes from wheat seeds was also developed. This involved aseptically slicing individual surface-sterilized seeds into 1- to 2-mm-thick slices and placing them onto the isolation media. These slices did not germinate and were left for up to 4 weeks at 27°C for the endophytes to appear.

SEM.

Incubated plant fragments on which the growth of actinobacteria was visible were fixed onto cryomicroscope stubs with TissueTek at room temperature. The stubs were then placed directly into the cold preparation cryotransfer unit (Oxford Instruments, Oxford, United Kingdom). After transfer to the cryostage of the scanning electron microscope (SEM; JEOL 6400), specimens were etched lightly by slowly warming them to 183°K. This was done under observation at 1 kV until faint cell outlines were detected. At this point specimens were recooled to 153°K and then coated with 50 nm of evaporated high-purity Al. Coated specimens were observed at 7 to 15 kV, and images were recorded as video prints and on Tmax 100 film (28).

DNA extraction from actinobacteria.

For each isolate, a loopful of mycelium and spores was scraped from colonies grown on agar media and suspended in 400 μl of saline-EDTA (0.15 M NaCl, 0.1 M EDTA [pH 8.0]) by vortexing. To this mixture, lysozyme was added to a final concentration of 1 mg ml−1, followed by incubation at 37°C for 45 min. Subsequently, 10 μl of 1% (wt/vol) proteinase K and 10 μl of 25% sodium dodecyl sulfate was added, and the mixed solution was incubated at 55°C for 30 min. A further 10 μl of 25% sodium dodecyl sulfate was added before further incubation at 55°C for 30 min. The lysates were centrifuged (15,000 × g, 5 min) to pellet the cell debris before sequential extractions with Tris-EDTA-equilibrated phenol, followed by chloroform. The aqueous phase was precipitated with 2 volumes of ethanol and washed with 70% ethanol. The DNA was desalted by using a Prep-a-Gene kit (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer's instructions with 10 μl of DNA-binding matrix.

Amplification and sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene.

PCR was done with the universal 16S primers designed to amplify the region between positions 27 and 765 of the 16S rRNA gene in actinobacteria. The primers were designated 27f (5′-AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG) and 765r (5′-CTGTTTGCTCCCCACGCTTTC). The PCR was carried out in 100-μl reaction volumes with the following reagents: 4 μl of 27f (200 ng μl−1), 4 μl of 765r (200 ng μl−1), 20 μl of 5× Taq buffer (5% 40 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 40% 25 mM MgCl2, 50% 10× PCR buffer, 5% water), 67 μl of water, 1 μl of Taq polymerase (2 U μl−1), and 4 μl of template DNA. The reactions were subjected to the following temperature cycling profile: 94°C for 8 min; followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 45°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 2 min; followed by 45°C for 1 min, and finally 72°C for 10 min. The PCR products were purified by using a Wizard PCR Prep DNA purification kit (Promega) before automated sequencing with the 765r primer. A total of 19 selected isolates were used for full 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) gene sequencing. For these isolates, the region from positions 27 to 1492 of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified with 27f and 1492r (5′-TACGGYTACCTTGTTACGACTT) primers. The temperature cycling profile was identical to the amplification of the region from positions 27 to 765 of the 16S rRNA gene described above. The resultant 1,466-bp product was purified as described for the partial 16S rDNA PCR products. Bidirectional sequencing of the complete 1,465-bp PCR product was done with four primers. These were 27f, 765r, 704f (5′-GTAGCGGTGAAATGCGTAGA), and 1492r. The resultant 16S rDNA sequences were compared to the GenBank databases by using BLASTN (2).

NJ phylogenetic analysis.

Neighbor-joining (NJ) phylogenetic analysis was performed on partial and full 16S rDNA sequences with Bacillus subtilis (accession no. NC000964) as the outgroup. The sequences were first aligned by using CLUSTALX (39). The resultant multiple alignment file was edited by using BioEdit version 5. The overhanging ends were removed from both ends of the sequence to ensure all sequences were of the same length. The tree was constructed with the MEGA software package by using an NJ method with the Kimura two-parameter model (24). Gaps were treated by pairwise deletion, i.e., gaps were removed from the sequence during the pairwise distance computation. Bootstrap analysis was done by using 5,000 pseudoreplications.

Screening for nec1, a pathogenicity determinant on the PAI of plant-pathogenic Streptomyces spp.

DNA was prepared for each of the isolates by using the protocol described above. A range of known plant-associated Streptomyces type cultures was used as controls for the screening assays. These included S. scabies ATCC 49173, S. acidiscabies ATCC 49003, S. setonii ATCC 25497, and S. caviscabies ATCC 51928. The nec1 gene fragment was amplified with the Nf (5′-ATGAGCGCGAACGGAAGCCCCGGA) and Nr (5′-GCAGGTCGTCACGAAGGATCG) primers (9). These primers were used in the following 25-μl reaction mixture: primers (200 ng μl−1), 1 μl each; 5× Taq buffer (including deoxynucleoside triphosphates), 5 μl; water, 15.5 μl; Taq polymerase (2 U μl−1), 0.5 μl; and template DNA, 2 μl. The following thermal profile was used: 95°C for 2 min; followed by 30 cycles of 95°C for 1 min, 60°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 2 min; and then a 15°C soak. The Streptomyces strains were also screened for the ability to produce thaxtomin by extracting well-developed colonies of 10-day-old cultures and testing the concentrated extracts by using a thin-layer chromatography method described elsewhere (26).

RESULTS

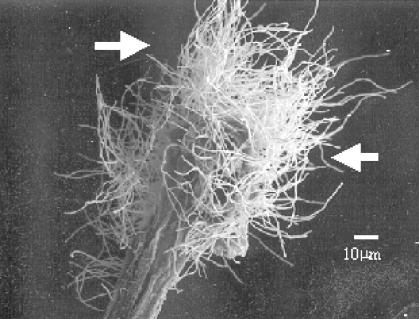

Actinobacteria were recovered from surface-sterilized wheat root tissue at all sampling times and points over the growing season. Figure 1 illustrates actinobacterial hyphae emerging from wheat root fragments using cryo-SEM. The images were taken from root fragments that were incubated for 4 weeks on isolation plates. Observations on the frequency of endophyte isolation (data not shown) suggest that the nutrient-poor media such as HV, TWYE, and YECD were most effective for the isolation of endophytic actinobacteria from wheat root tissue. This favored the emergence of actinobacteria from the plant fragments before faster-growing fungi could overgrow the plate and mask the presence of the actinobacteria, even in the presence of antifungal compounds. Analysis of the isolation frequency of the endophytic actinobacteria shows that more endophytic actinobacteria were isolated from younger plants, with 77% of the isolates recovered from plants that were harvested within 11 weeks of germination. It was also observed that plants from sandy soils contained a higher number of actinobacterial endophytes, although this needs to be confirmed by a larger study.

FIG. 1.

SEM images (×500 magnification) of Streptomyces aerial hyphae emerging from surface-sterilized wheat root fragments after 4 weeks of incubation on an isolation plate. The arrows indicate the Streptomyces mycelium.

An evaluation of the surface sterilization protocol was carried out to ascertain that the actinobacteria obtained could not survive exposure to the sterilization protocol. None of the representative isolates, including spore-bearing actinobacteria, survived the sterilization treatment either in suspension or as seed coatings on wheat seed. On the other hand, luxuriant growth for all five actinobacteria and two pseudomonads used was observed from the treated seeds, as well as from the washed seeds. This indicated that simple washing steps did not remove the microbial coating and that the surface sterilization protocol was effective.

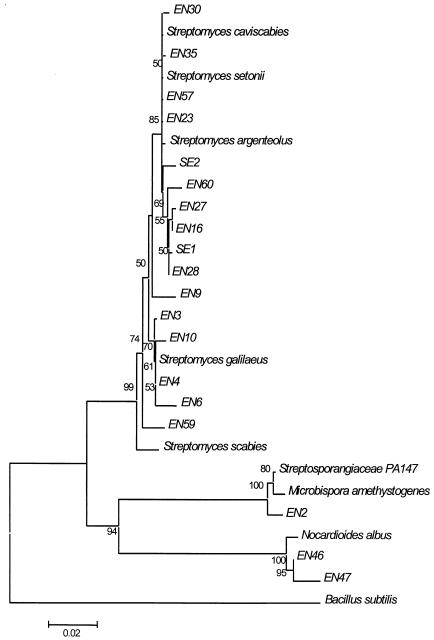

Partial 16S rDNA sequencing was used initially to identify the actinobacterial isolates to the genus level and to determine whether there were clusters of similar organisms. The results of the partial 16S rDNA sequencing of the isolates (Table 1) indicated that 88% of the isolates matched database entries from the genus Streptomyces. A further 12% of the isolates matched database entries describing other actinobacterial genera, including Microbispora, Micromonospora, and Nocardiodes. These data indicate that, in general, Streptomyces spp. were the most widely distributed actinobacterial genus among the cultures isolated from wheat roots, with a dominance of S. caviscabies/S. setonii-like and S. galilaeus isolates. The full 16S rDNA sequences were determined for selected isolates (Table 2), and these sequences were used to construct the NJ phylogenetic tree shown in Fig. 2.

TABLE 1.

Identification of the actinobacterial endophyte isolates based on partial sequencing of the 750-bp region of the 16S rDNA gene

| Identificationa | % Similarity | No. of isolates |

|---|---|---|

| S. galilaeus or Streptomyces sp. strain LS1 or EF52 | 92-98 | 14 |

| S. caviscabies, S. setonii, or S. argenteolus | 92-96 | 15 |

| S. scabies | 91-93 | 5 |

| S. bikiniensis | 91 | 2 |

| S. tendae | 94-98 | 2 |

| S. maritimus | 92-95 | 3 |

| S. pseudovenezuelae | 92-93 | 3 |

| Streptomyces sp. | 90-94 | 7 |

| Micromonospora sp. | 91-94 | 4 |

| Nocardiodes albus | 95 | 2 |

| Streptosporangium/Microbispora | 94 | 1 |

Nearest match(es).

TABLE 2.

Closest BLASTN matches for the full 16S rDNA sequence of the actinobacterial isolates

| Isolate | Accession no. | Strongest 16S rDNA sequence match (BLASTN)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organism | Accession no. | Bits | % | ||

| EN2 | AY148073 | Streptosporangiaceae strain PA147 | AF223347 | 1,830 | 94 |

| Microbispora amethystogenes | U48988 | 1,709 | 93 | ||

| EN3 | AY148077 | Streptomyces galilaeus | AB045878 | 2,775 | 99 |

| EN4 | AY148080 | Streptomyces galilaeus | AB045878 | 2,708 | 99 |

| EN6 | AY148085 | Streptomyces pseudovenezuelae | AJ399481 | 1,667 | 95 |

| EN9 | AY148087 | Streptomyces bikiniensis | X79851 | 2,573 | 98 |

| EN10 | AY148071 | Strptomyces fimbriatus | AB045868 | 2,391 | 96 |

| Streptomyces sp. strain ASSF13 | AF012736 | 2,002 | 95 | ||

| EN16 | AY148072 | Streptomyces caviscabies | AF112160 | 1,994 | 95 |

| EN22 | AY291590 | Streptomyces peucetius | AB045887 | 2,579 | 98 |

| EN23 | AY148074 | Streptomyces caviscabies | AF112160 | 2,825 | 99 |

| EN27 | AY148075 | Streptomyces caviscabies | AF112160 | 1,776 | 94 |

| EN28 | AY148076 | Streptomyces caviscabies | AF112160 | 2,409 | 96 |

| EN30 | AY148078 | Streptomyces argenteolus | AB045872 | 2,706 | 98 |

| EN35 | AY148079 | Streptomyces caviscabies | AF112160 | 2,512 | 97 |

| EN43 | AY291589 | Micromonospora yulongensis | X92626 | 2,627 | 98 |

| EN46 | AY148081 | Nocardioides albus | X53211 | 2,516 | 98 |

| EN47 | AY148082 | Nocardioides albus | X53211 | 2,769 | 99 |

| EN57 | AY148083 | Streptomyces caviscabies | AF112160 | 2,684 | 99 |

| EN59 | AY148084 | Streptomyces galilaeus | AB045878 | 1,879 | 95 |

| EN60 | AY148086 | Streptomyces argenteolus | AB045872 | 2,375 | 96 |

| SE1 | AY148088 | Streptomyces caviscabies | AF112160 | 1,879 | 95 |

| SE2 | AY148089 | Streptomyces caviscabies | AF112160 | 2,528 | 97 |

FIG. 2.

NJ phylogenetic tree of the full 16S rDNA sequences from selected isolates. The sequence data for several closely related actinobacterial type cultures were recovered from GenBank and included in the tree. The accession numbers for the sequences are as follows: B. subtilis, NC_000964 (region 9809.0.11361); Microbispora amethystogenes, U48988; N. albus, X53211; S. scabies, D63862; S. galilaeus, AB045878; S. argenteolus, AB045872; S. setonii, D63872; S. caviscabies, AF112160; and Streptosporangiacae strain PA147, AF223347. The bootstrap values from 5,000 pseudoreplications are shown at each of the branch points on the tree.

Of the isolates in the Streptomyces genus, 40% displayed the highest 16S rDNA sequence similarity to isolates recovered from potato scab lesions, and half of these isolates showed the highest sequence similarity to S. caviscabies (ATCC 51928) and S. setonii (ATCC 25497). On media used to characterize streptomycetes (ISP media 2 to 4 [2]), these isolates form a morphologically uniform group characterized by colorless substrate mycelium, pale olive spore pigmentation, and the production of a brown diffusible pigment. In contrast, both the type cultures have cream to white spores and very low levels of diffusible pigment. In addition, the type cultures do not produce melanin, whereas the majority of the actinobacterial isolates produce this pigment. Full 16S rDNA sequencing confirmed that these isolates were most closely related to S. caviscabies and S. setonii. However, basic local alignment search tool (BLAST) results revealed that, with the exception of Streptomyces sp. strain EN23, the nucleotide identity was in the range of 94 to 97%, indicating that these isolates may constitute a new species within the Streptomyces genus. Detailed characterization of this group is currently being done in our laboratory, in comparison with the nearest type strains, to determine whether there are sufficient differences in phenotype to substantiate the classification of a new species. Isolates from this group were recovered at least once at each site over the growing season, indicating that this taxon is widespread in wheat in South Australia. These isolates were also recovered in the second year of sampling from all locations. Of further interest, the two isolates, SE1 and SE2, recovered from wheat seed cv. Excalibur also belonged to this new species, which closely matches S. caviscabies and S. setonii. This suggests that the S. caviscabies/S. setonii-like taxa may be seed-borne in wheat.

The NJ phylogenetic tree of the full 16S rDNA sequence data of selected isolates (Fig. 2) confirmed that the S. caviscabies/S. setonii-like isolates and the S. galilaeus-like isolates formed a distinct phylogenetic cluster. It was also interesting that S. argenteolus exhibited high 16S rDNA sequence similarity to this cluster, although the morphology of this species is quite different.

The partial 16S rDNA sequencing data indicated that three other non-Streptomyces genera were represented among the isolates recovered from surface-sterilized root tissue. These genera were Microbispora, Micromonospora, and Nocardioides. The complete 16S rDNA sequencing data indicated that isolate EN2 was a novel strain most closely related to Microbispora amethystogenes (93% similarity), isolate EN 43 was most closely related to Micromonospora yulongensis (98% similarity), and isolates EN46 and EN47 were most closely related to Nocardiodes albus (98 and 99% similarities, respectively).

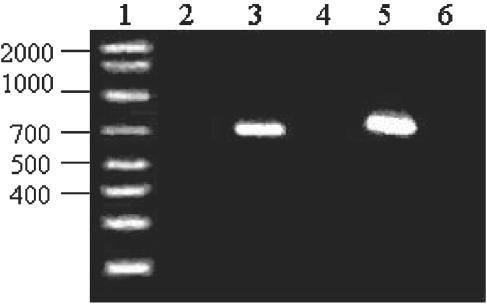

As shown in Fig. 3, the S. caviscabies and S. setonii type strains did not show the presence of the nec1 gene and did not produce thaxtomin in oatmeal agar, unlike the pathogenic S. scabies and S. acidiscabies type strains. None of the isolates recovered in this project that exhibited sequence similarity to S. caviscabies and S. setonii either carried the nec1 gene or produced thaxtomin, which suggests that these strains also are nonpathogenic. Streptomyces sp. strains EN9 and EN31, which displayed 16S rDNA sequence homology to S. bikiniensis and the pathogenic S. scabies, respectively, displayed the presence of the nec1 gene, although only the former strain produced thaxtomin.

FIG. 3.

nec1 screening in Streptomyces type strains: lane 1, molecular weight marker; lane 2, negative control; lane 3, S. acidiscabies; lane 4, S. caviscabies ATCC 51928; lane 5, S. scabies ATCC 49173; lane 6, S. setonii ATCC 25497.

DISCUSSION

This study is the first to isolate and identify endophytic actinobacteria associated with healthy wheat plants. Analysis of the frequency of isolation of endophytes indicates that more endophytic actinobacteria were isolated when the plants were younger and on nutrient-poor media. This favored the emergence of actinobacteria from the plant fragments before fungi could overgrow the plate and mask the presence of the actinobacteria. This effect was also noted by Crawford et al. (13) for the isolation of actinobacteria from soil. Higher concentrations of antifungal agents were not attempted since they may have had an adverse affect on actinobacterial growth. Fungal endophytes are known to be present in plants, including wheat (7), and it was observed that older wheat plants have a higher fungal colonization (25). Studies of the interactions between different groups of endophytic microorganisms within the host wheat plant have not yet been carried out but are necessary in order to obtain data on the colonization processes that occur in nature. Studies on the external rhizosphere populations during the growth of wheat plants have determined the fluctuations in actinobacterial and pseudomonad populations of the rhizoplane and rhizosphere (31, 32) and the increases in populations of Pseudomonas, Chryseobacterium, and Flavobacterium spp. in the presence of Take-all disease (29).

In the present study, we have shown that the surface sterilization protocol is effective in removing all surface-adhering microorganisms, including spore-bearing actinobacteria, and that the isolates obtained can be considered to be true endophytes. Although this evidence is comprehensive, in a related study we present evidence of the presence of one of our strains, tagged with enhanced green fluorescent protein, within the tissues of the host plant (10).

It is interesting that the predominance of Streptomyces spp. among the actinobacterial endoflora of wheat that was observed in the present study was also noted by Sardi et al. (35) on field crops and Italian native plants and as a result of the molecular characterization of the bacterial population within potatoes (36). However, these results would suggest that the endophytic microflora of wheat is different from that reported in maize, where the genus Microbispora, followed by Streptomyces and Streptosporangium, was most commonly isolated (9). However, the differences between the observed endophytic actinobacterial communities between these plants are the relative proportions of one genus to another, possibly due to bias in the isolation method, since all of the genera isolated from maize plant tissue were also isolated from wheat.

Microbispora spp. have been isolated from surface-sterilized tissue of a number of other plant species (15, 33). Therefore, it appears that species from a select group of actinobacterial genera, most notably Streptomyces, Microbispora, and Streptosporangium, are able to associate with a wide range of host plants.

The higher frequency of Micromonospora spp. in plants than in soil (20) may indicate that they have formed a beneficial association with plants, conferring a selective advantage due to the ability of some Micromonospora spp. to parasitize the fungal pathogens Pythium and Phytophthora spp. (15, 16).

Within the Streptomyces genus, two particular taxa, one related to S. galilaeus and one related to S. caviscabies and S. setonii, were widely distributed in the root tissues of sample plants. Of particular note are the group of isolates related to S. caviscabies and S. setonii. On the basis of the difference in homology compared to the 16S rDNA sequence of the nearest matching type strains, as well as based on morphological differences, these isolates appear to belong to a new species that is widely distributed in wheat plants in South Australia. Isolates from wheat seed cv. Excalibur suggests that these actinobacteria may be carried within the seed from one plant generation to the next. Our data also indicate that S. caviscabies (and the related S. setonii) may not be a plant pathogen as originally reported (18). The type strain of this species (ATCC 51928) does not have two markers of the PAI common to all plant-pathogenic Streptomyces, namely, the nec1 gene and the ability to produce thaxtomin (8, 9, 21, 22, 26). Similarly, none of the S. caviscabies/S. setonii-like isolates recovered by us carried the nec1 gene or produced thaxtomin. The recovery of isolates related to S. caviscabies from healthy wheat and the apparent lack of the PAI in the type strain suggest that the true ecological role of this species may be as an endophyte in a number of plant species. Therefore, it is likely that S. caviscabies may have been present in potatoes as an endophyte, which led to its isolation from scab tissue and an erroneous designation as a pathogen (18). In further extensive studies in our laboratory, no pathogenic traits have been observed when these actinobacterial isolates were reinoculated onto wheat plants (12).

Another interesting observation is that the organisms that were widely distributed had been previously reported to have an association with plants. The S. caviscabies-like isolates have been isolated from potato scabs, as has Streptomyces sp. strain EF-52 (GenBank accession no. AF11219). S. galilaeus has been found to produce the compound homoalanosine, which is known to have antimicrobial, insecticidal, and plant growth regulatory activity (34).

The isolation of microorganisms from within the tissue of healthy wheat suggests that the host derives some benefit from harboring the endophyte. In this case the advantage may take the form of a secondary metabolite produced by the endophyte, since actinobacteria are well known for their ability to produce a broad range of antibacterial, antifungal, and plant growth-regulatory metabolites (17). Further experiments to determine the role of these endophytes in the development of the host plant are ongoing in our laboratory (11). This study reveals a novel plant-microbe interaction with implications for biotechnological application of these actinobacterial endophytes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Australian Grains Research and Development Corp.

We thank Stephen Donellan of the South Australian Museum for assistance with the phylogenetic analysis and Margaret McCully of CSIRO Plant Industry, Canberra, Australia, for the cryo-SEM micrographs.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schäffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atlas, R. M. 1993. Alphabetical listing of media, p. 455-462. In L. C. Parks (ed.), Handbook of microbiological media. CRC Press, Inc., Boca Raton, Fla.

- 3.Baker, D. D. 1988. Opportunities for autoecological studies of Frankia, a symbiotic actinomycete, p. 271-276. In Y. Okami, T. Beppu, and H. Ogawa (ed.), Biology of actinomycetes. Proceedings of the Seventh International Symposium on the Biology of Actinomycetes. Japan Scientific Societies Press, Tokyo, Japan.

- 4.Baker, D. D., J. D. Tjepkema, and C. R. Schwintzer. 1990. The biology of Frankia and actinorhizal plants. Academic Press, Inc., San Diego, Calif.

- 5.Benson, D. R., and W. B. Silvester. 1993. Biology of Frankia strains, actinomycete symbionts of actinorhizal plants. Microbiol. Rev. 57:293-319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berdy, J. 1989. The discovery of new bioactive microbial metabolites: screening and identification. Prog. Indust. Microbiol. 27:3-25. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bills, G. F. 1996. Isolation and analysis of endophytic fungal communities from woody plants, p. 31-65. In S. C. Reddin and L. M. Carris (ed.), Endophytic fungi of grasses and woody plants. APS Press, St. Paul, Minn.

- 8.Bukhalid, R., S. Y. Chung, and R. Loria. 1998. nec1, a gene conferring a necrogenic phenotype is conserved in plant-pathogenic Streptomyces spp. and linked to a transposase pseudogene. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 11:960-967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bukhalid, R., and R. Loria. 1997. Cloning and expression of a gene from Streptomyces scabies encoding a putative pathogenicity factor. J. Bacteriol. 179:7776-7783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coombs, J. T., and C. M. M. Franco. Visualization of an endophytic Streptomyces species in wheat seed. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:4260-4262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Coombs, J. T., C. M. M. Franco, and R. Loria. 2003. Complete sequencing and analysis of pEN2701, a novel 13-kb plasmid from an endophytic Streptomyces sp. Plasmid 49:86-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coombs, J. T., P. P. Michelsen, and C. M. M. Franco. Evaluation of endophytic actinobacteria as antagonists of Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici in wheat. Biol. Control, in press.

- 13.Crawford, D. L., J. M. Lynch, J. M. Whipps, and M. A. Ousley. 1993. Isolation and characterization of actinomycete antagonists of a fungal root pathogen. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:3899-3905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Araujo, J. M., A. C. da Silva, and J. L. Azevedo. 2000. Isolation of endophytic actinomycetes from roots and leaves of maize (Zea mays L.). Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 434:47-451. [Google Scholar]

- 15.El-Tarabily, K. A., G. E. S. J. Hardy, K. Sivasithamparam, A. M. Hussein, and D. I. Kurtboke. 1997. The potential for the biological control of cavity-spot disease of carrots, caused by Pythium coloratum, by streptomycete and non-streptomycete actinomycetes. New Phytol. 137:495-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Filinow, A. B., and J. L. Lockwood. 1985. Evaluation of several actinomycetes and the fungus Hyphochitrium catenoides as biocontrol agents for Phytopthora root rot of soybean. Plant Dis. 69:1033-1036. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franco, C. M. M., and L. E. L. Coutinho. 1991. Detection of novel secondary metabolites. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 11:193-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goyer, C., E. Faucher, and C. Beaulieu. 1996. Streptomyces caviscabies sp. nov., from deep-pitted lesions in potatoes in Quebec, Canada. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 46:635-639. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hayakawa, M. T., and H. Nonomura. 1987. Humic acid-vitamin agar, a new method for the selective isolation of soil actinomycetes. J. Ferment. Bioeng. 65:501-509. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hayakawa, M. T., T. Sadakata, T. Kijura, and H. Nonomura. 1991. New methods for the highly selective isolation of Micromonospora and Microbispora from soil. J. Ferment. Bioeng. 72:320-326. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Healy, F. G., R. A. Bukhalid, and R. Loria. 1999. Characterization of an insertion sequence element associated with genetically diverse plant pathogenic Streptomyces spp. J. Bacteriol. 181:1562-1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Healy, F. G., M. Wach, S. B. Krasnoff, D. M. Gibson, and R. Loria. 2000. The txtAB genes of the plant pathogen Streptomyces acidiscabies encode a peptide synthetase required for phytotoxin thaxtomin A production and pathogenicity. Mol. Microbiol. 38:1-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kieser, T., M. J. Bibb, M. J. Buttner, K. F. Chater, and D. A. Hopwood (ed.). 2000. Practical Streptomyces genetics. John Innes Centre, Norwich, England.

- 24.Kumar, S., K. Tamura, I. B. Jakobsen, and M. Nei. 2001. MEGA2: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis software. Arizona State University, Tempe. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Larran, S., A. Perello, M. R. Simon, and V. Moreno. 2002. isolation and analysis of endophytic microorganisms in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) leaves. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 18:683-686. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loria, R., R. A. Bukhalid, R. A. Creath, R. H. Leiner, M. Olivier, and J. C. Steffens. 1995. Differential production of thaxtomins by pathogenic Streptomyces species in vitro. Phytopathology 85:537-541. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mayfield, C. I., S. T. Williams, S. M. Ruddick, and H. L. Hatfield. 1972. Studies on the ecology of actinomycetes in soil. IV. Observations on the form and growth of streptomycetes in soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 4:79-91. [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCully, M. E., M. W. Shane, A. N. Baker, C. X. Huang, L. E. C. Ling, and M. J. Canny. 2000. The reliability of cryoSEM for the observation and quantification of xylem embolisms and quantitative analysis of xylem sap in situ. J. Microsc. 198:24-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McSpadden-Gardener, B. B., and D. M. Weller. 2001. Changes in populations of rhizosphere bacteria associated with Take-all disease of wheat. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4414-4425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller, H. J., G. Henken, and J. A. Van Veen. 1989. Variation and composition of bacterial populations in the rhizospheres of maize, wheat and grass cultivars. Can. J. Microbiol. 35:656-660. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller, H. J., E. Liljeroth, G. Henken, and J. A. Van Veen. 1990. Fluctuations in the fluorescent pseudomonad and actinomycete populations of the rhizosphere and rhizoplane during the growth of spring wheat. Can. J. Microbiol. 36:254-258. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller, H. J., E. Liljeroth, M. J. E. I. M. Willemsen-De Klein, and J. A. Van Veen. 1990. The dynamics of actinomycetes and flourescent pseudomonads in wheat rhizoplane and rhizosphere. Symbiosis 9:389-391. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okazaki, T., K. Takahashi, M. Kizuka, and R. Enokita. 1995. Studies on actinomycetes isolated from plant leaves. Annu. Rev. Sankyo Res. Lab. 47:97-106. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pachlatko, J. P. 1998. Natural products in crop protection. Second International Electronic Conference on Synthetic Organic Chemistry (ECSOC-2). ECSOC, Basel, Switzerland. [Online.] http://www.ecsoc2.hec.ru/d1001/d1001.htm.

- 35.Sardi, P., M. Saracchi, S. Quaroni, B. Petrolini, G. E. Borgonovi, and S. Merli. 1992. Isolation of endophytic Streptomyces strains from surface-sterilized roots. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:2691-2693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sessitch, A., B. Reiter, U. Pfeifer, and E. Wilhelm. 2001. Cultivation-independent population analysis of bacterial endophytes in three potato varieties based on eubacterial and actinomycetes-specific PCR of 16S rRNA genes. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 1305:1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Siciliano, S. D., C. M. Theoret, J. R. de Freitas, P. J. Hucl, and J. J. Germida. 1998. Differences in the microbial communities associated with the roots of different cultivars of canola and wheat. Can. J. Microbiol. 44:844-851. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thompson, J. D., T. J. Gibson, F. Plewniak, F. Jeanmougin, and D. G. Higgins. 1997. CLUSTALX, ver. 1.81: the CLUSTALX windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 24:4876-4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]