Abstract

Larvae of the mosquito Toxorhynchites rutilus (Coquillett) prey upon other container-dwelling insects, including larvae of Aedes albopictus (Skuse), which is native to Asia but was introduced into the United States, and on the native tree hole mosquito Ochlerotatus triseriatus (Say). Previous work has established that O. triseriatus adopts low-risk behaviors in the presence of predation risk from T. rutilus. It is unknown whether introduced A. albopictus show a similar response to this predator. Behavior of fourth instars of A. albopictus or O. triseriatus was recorded in water that had held either A. albopictus or O. triseriatus larvae alone (control) and in water that had held T. rutilus larvae feeding on either A. albopictus or O. triseriatus (predation). Activity and position of larvae were recorded in 30-min instantaneous scan censuses. In response to water-borne cues to predation, O. triseriatus adopted low-risk behaviors (more resting, less feeding and movement), but A. albopictus did not change its behavior. We also tested the species specificity of the cues by recording the behavior of A. albopictus in water prepared using O. triseriatus and vice versa. O. triseriatus adopted low-risk behaviors even in predation water prepared by feeding T. rutilus with A. albopictus, but A. albopictus did not alter its behavior significantly between predation and control treatments prepared using O. triseriatus. Thus, A. albopictus does not seem to respond behaviorally to cues produced by this predator and may be more vulnerable to predation than is O. triseriatus.

Keywords: predation risk, Toxorhynchites, Ochlerotatus triseriatus, Aedes albopictus

Predation, or perceived risk of predation, induces facultative changes in behavior of mosquito larvae, which can affect their vulnerability to predation (Juliano and Reminger 1992, Grill and Juliano 1996, Juliano and Gravel 2002). When larvae are exposed to consistent predation, there can be rapid evolution of these behavioral responses (Juliano and Gravel 2002), suggesting that the responses are adaptive. The Asian container-dwelling mosquito Aedes albopictus (Skuse) was introduced into the United States in the mid-1980s and has increased its North American range to include most of the southeastern United States (Hawley et al. 1987, Moore 1999). In southern North America, A. albopictus co-occurs in containers with the mosquito Toxorhynchites rutilus (Coquillett), which prey on other mosquito larvae, including A. albopictus (Campos and Lounibos 2000). Ochlerotatus triseriatus (Say), a container-dwelling mosquito native to North America, shows facultative changes in behavior upon perceiving water-borne cues to predation from T. rutilus that seem to lessen the risk of predation (Juliano and Reminger 1992, Juliano and Gravel 2002). In mosquitoes, prey behavior strongly affects vulnerability to predation by Toxorhynchites (Rubio et al. 1980, 1981; Juliano and Reminger 1992; Grill and Juliano 1996). There have been numerous studies on the competitive interactions of A. albopictus with North American filter-feeding mosquito species such as Aedes aegypti (L.) and O. triseriatus, and they have shown that O. triseriatus is usually an inferior competitor compared with A. albopictus (Ho et al. 1989, Livdahl and Willey 1991, Novak et al. 1993, Teng and Apperson 2000), but relatively few studies have been done on the vulnerability of A. albopictus to North American predators (Lounibos et al. 2001) or on the impact of predation on the competitive interactions of A. albopictus with other species, especially O. triseriatus. Because A. albopictus is an introduced species that has only recently encountered the predator T. rutilus, it is not known whether A. albopictus larvae modify their behavior in response to the threat of T. rutilus predation. A. albopictus does encounter other species of Toxorhynchites in its native Asia (Hawley 1988), but there has been no investigation of whether A. albopictus modifies behavior in response to these species. Toxorhynchites spp. are primarily ambush predators and seem to detect the prey by using mechanoreceptors (Rubio et al. 1980, 1981; Steffan and Evenhuis 1981). So, highly active prey will likely be more vulnerable to predation compared with less active or resting individuals (Rubio et al. 1980, 1981; Russo 1986; Juliano and Reminger 1992; Grill and Juliano 1996; Juliano and Gravel 2002). Individuals that are highly active can find and harvest more resources and at the same time have more chance of encountering predators (Grill and Juliano 1996). So, behavior, and behavioral change, may play an important role in determining the outcome of both predation and interspecific competition.

We had two specific objectives for this study. First, we wished to determine whether A. albopictus shows the same shift to low-risk behaviors upon perceiving water-borne cues to predation that is shown by O. triseriatus. Aedesalbopictus co-occurs with Asian Toxorhynchites (Hawley 1988), and if predatory behavior and tactics of those Asian predators are similar to those of North American T. rutilus, then the degree of change in behavior should be similar for the two species. Second, we wished to determine whether the water-borne cues from predation that may be perceived by O. triseriatus and A. albopictus are species specific.

Methods

Comparing Prey Behavior

We collected O. triseriatus from tree holes at Parklands Merwin Reserve near Normal, IL, and A. albopictus from tires and tree holes at Vero Beach, FL. Both the species were collected as larva and pupae, raised to adulthood in environmental chambers, and propagated in 0.6-m3 cages. Toxorhynchites rutilus is relatively rare in Normal (Juliano et al. 1993), so we collected them as larvae in the field at Vero Beach. Toxorhynchites rutilus from this site prey regularly upon O. triseriatus (Juliano and Gravel 2002).

The behaviors of A. albopictus and O. triseriatus larvae were recorded on videotape 1 d after molting to the fourth instar, while they were held in water treated in one of two ways. Control water had held larval conspecifics of each of the species, whereas predation water had held T. rutilus feeding on conspecifics of each of the species. For the predation treatment, one T. rutilus fourth instar was held for 5 d in a 50-ml cup with 50 ml of water and 10 O. triseriatus or A. albopictus larvae, depending upon the test species. Larvae offered as prey for water preparation were counted daily and any missing larvae were replaced with additional larvae. For the control treatment, 10 O. triseriatus or A. albopictus larvae were held 5 d without food. Any larvae that died were replaced. For both predation and control water, some detritus (e.g., feces, bits of eaten prey) accumulated during the 5-d period, and this solid material remained in the treatment water during the trial.

Aedes albopictus and O. triseriatus larvae that were used as test subjects were offspring of field-collected individuals. They were hatched and held individually in 18-ml vials with 10 ml of water. These larvae were fed with liver powder suspension (LPS) prepared by mixing 0.3 g of bovine liver powder with 1 liter of water. This food suspension was dispensed via pipetting from a beaker held on a stirring plate to ensure homogeneous delivery of food to larvae (Juliano and Gravel 2002). We provided each larva with 0.5 ml of LPS on day 1 and 1 ml every 2 d thereafter. Once the larvae were fourth instars, they were held individually in 50-ml cups with 30 ml of water and no food for 24 h to standardize hunger before transfer to the treatment water for behavior recording.

Species Specificity of Cues

We prepared the predation water and control water as described in the previous section. We first recorded the behavior of O. triseriatus fourth instars in both control and predation water prepared using O. triseriatus, and then recorded the behavior of A. albopictus fourth instars in the same water. Similarly, we recorded behavior of A. albopictus fourth instars in water prepared using A. albopictus and then subsequently recorded the behavior of O. triseriatus fourth instars in the same water. In each case, test larvae were observed only once, in one kind of treatment water, but the prepared treatment water was used for one test larva of each species.

Videotaping

We recorded the behaviors of the larvae in the treatment waters on an S-VHS videotape for 30 min. Each larva was given a 10-min acclimation period in the treatment cup before initiating behavior recording. A single 30-min clip had images of a maximum of six treatment cups at a time due to resolution constraints. Each clip had all of the treatments represented.

Observation Protocol

From the videotape, activity and position of the each larva were recorded every minute for 30 min in instantaneous scan censuses (Martin and Bateson 1986, Juliano and Gravel 2002). Activities were classified into four categories: 1) browsing, the larva moving along the surfaces of the cup propelled by feeding movements of the mouth-parts; 2) resting, the larva completely still and not feeding; 3) filtering, the larva drifting through the water column, propelled by feeding movements of mouthparts; and 4) thrashing, the larva propelling itself through the water by vigorous lateral flexion of the body (Juliano and Reminger 1992, Grill and Juliano 1996, Juliano and Gravel 2002). Positions were classified into four categories: 1) surface, the larva’s spiracular siphon in contact with the surface; 2) bottom, the larva within 1 mm of the bottom of the cup; 3) wall, the larva within 1 mm of the sides of the cup; and 4) middle, the larva not in contact with the surface, and >1 mm from the cup’s surfaces. For T. rutilus preying upon O. triseriatus, Juliano and Reminger (1992) showed that among positions, the surface is the least likely to lead to predation, the bottom is the most likely to lead to predation, and middle and wall are intermediate, and among activities, resting is the least likely to lead to predation, thrashing is the most likely to result in predation, and the two feeding behaviors are intermediate.

Statistical Analysis

We converted the activities and positions to proportions. To reduce the number of variables and to obtain uncorrelated descriptors of behavior, we did principal component analysis on activities and positions (PROC FACTOR, SAS Institute 1990; Juliano and Gravel 2002). Principal components (PCs) with Eigen values >1.0 were retained for further analysis, whereas those with values <1.0 were ignored (Hatcher and Stepansky 1994). Principal component scores were analyzed using multiple analysis of variance (MANOVA) (for comparison of prey behavior) or analysis of variance (ANOVA) (for testing species specificity) (PROC GLM, SAS Institute 1990). We interpreted the results from the MANOVA by using canonical coefficients (Scheiner 2001) that quantify the contributions of the individual principal components in producing significant multivariate differences. We used Tukey–Kramer multiple comparisons between predation and control least-squares means within each species for the behavior experiment. We used Tukey–Kramer multiple comparisons among treatment least-squares means for pairwise comparisons of species specificity treatments.

Results

Comparing Prey Behavior

There were significant positive and negative correlation’s between position and activity categories. Resting was positively correlated with surface and negatively correlated with thrashing, browsing, and wall (Table 1). Browsing was positively correlated with wall and bottom.

Table 1.

Correlation’s of activities and positions for the interspecific comparison experiment

| Thrashing | Browsing | Filtering | Surface | Bottom | Wall | Middle | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resting | −51 | −90 | −12 | 93 | −36 | −76 | −40 |

| Thrashing | 19 | −21 | −43 | 11 | 24 | 59 | |

| Browsing | −6 | −86 | 31 | 84 | 4 | ||

| Filtering | −14 | 22 | −18 | 49 | |||

| Surface | −56 | −66 | −45 | ||||

| Bottom | −18 | 29 | |||||

| Wall | −4 |

All data pooled. Boldfaced numbers represent significant (P < 0.05) correlation’s.

Three PCs summarized 87% of the variation in activity and position (Table 2). Rotated factor pattern for PC1 showed large positive coefficients for browsing and wall and large negative coefficients for resting and surface. So, PC1 quantifies allocation time between browsing at the wall and resting at the surface (Table 3). PC2 quantifies time allocation between filtering at the bottom and middle and other behaviors. PC3 quantifies time allocation between thrashing in the middle and other behaviors. Higher PC scores in each case indicate greater frequencies of the activities and positions with large positive factor loadings, and lower frequencies of the activities and positions with large negative factor loadings (highlighted in Table 3).

Table 2.

Principal component analysis for the interspecific comparison experiment

| PC1 | PC2 | PC3 | PC4 | PC5 | PC6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eigen value | 3.92 | 1.82 | 1.17 | 0.87 | 0.13 | 0.06 |

| Proportion of variance | 0.49 | 0.22 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Cumulative proportion of variance | 0.49 | 0.72 | 0.87 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

Principal components in bold are those with Eigen values >1 that were retained for behavior analysis.

Table 3.

Varimax rotated factor pattern for the interspecific comparison experiment

| Response variables | PC1 | PC2 | PC3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resting | −90 | −21 | −35 |

| Thrashing | 23 | −17 | 93 |

| Browsing | 99 | 07 | −03 |

| Filtering | −11 | 83 | −01 |

| Surface | −86 | −36 | −31 |

| Bottom | 25 | 71 | 10 |

| Wall | 89 | −30 | 02 |

| Middle | 02 | 51 | 80 |

| Interpretation | Browsing, wall vs. resting, surface | Filtering, bottom, middle vs. other behaviors | Thrashing, middle vs. other behaviors |

Values >0.4 are listed in boldface; they indicate strong loadings on each principal component.

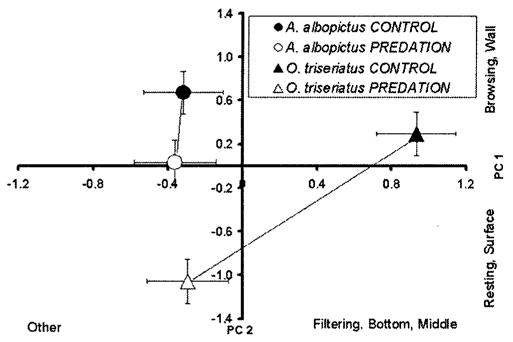

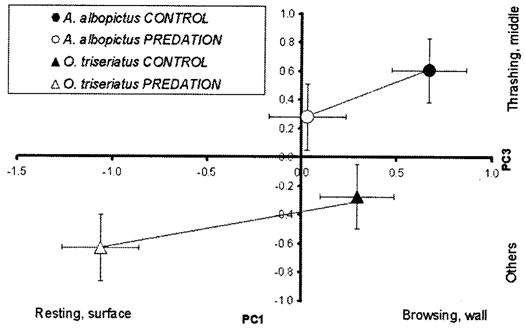

There was a significant interaction of species and treatment in MANOVA (Table 4), which resulted primarily from scores on PC1 (frequent resting, surface) and PC2 (frequent filtering, bottom, middle). For both PC1 and PC2, behaviors of A. albopictus did not differ significantly between control and predation water treatments (PC1, P = 0.1181 and PC2, P = 0.9989) (Fig. 1). In contrast, O. triseriatus’s behaviors differed significantly between control and predation water treatments (PC1, P = 0.0001 and PC2, P = 0.0010) (Fig. 1). Ochlerotatus triseriatus reduced browsing at the wall and filtering and thrashing in the middle considerably in predation water compared with control and increased resting at the surface (Figs. 1 and 2). In predation water, A. albopictus did not significantly reduce the frequency of browsing and thrashing in the middle compared with control water (Figs. 1 and 2). PC2 shows that even in the control water A. albopictus differs considerably in behavior from O. triseriatus (Figs. 1 and 2). A. albopictus spent less time filtering at the bottom and middle compared with O. triseriatus, which allocated more time to filtering at the bottom and middle in the absence of predation risk (Fig. 2).

Table 4.

MANOVA table for the behavior patterns in the interspecific comparison experiment

| Standardized canonical coefficients

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | df | Den df | Pillai’s Trace | P | PC1 | PC2 | PC3 |

| Species (S) | 3 | 56 | 0.491 | <0.0001 | 0.971 | −0.487 | 0.969 |

| Treatment (T) | 3 | 56 | 0.461 | <0.0001 | 1.239 | 0.568 | 0.575 |

| S * T | 3 | 56 | 0.178 | 0.0114 | 0.876 | 0.989 | 0.186 |

Magnitudes of standardized canonical coefficients indicate the degree of contribution by each factor to the significant MANOVA effect.

Fig. 1.

Plot of PC1 and PC2 (means ± SE). Activities and positions most closely associated with large positive or large negative PC scores are indicated parallel to each axis. Lines connect means for predation and control treatments for each species. For A. albopictus, PC1 and PC2 did not differ significantly between control and predation water treatments (PC1, P = 0.1181 and PC2, P = 0.9989). For O. triseriatus, PC1 and PC2 differed significantly between control and predation water treatments (PC1, P = 0.0001 and PC2, P = 0.0010) (Tukey–Kramer multiple comparisons).

Fig. 2.

Plot of PC1 and PC3 (means ± SE). Activities and positions most closely associated with large positive or large negative PC scores are indicated parallel to each axis. Lines connect means for predation and control treatments for each species. For A. albopictus, PC1 and PC3 did not differ significantly between control and predation water treatments (PC1, P = 0.1181 and PC3, P = 0.7423). For O. triseriatus, PC1 differed significantly between control and predation water treatments (PC1, P = 0.0001) and PC3 did not differ significantly between control and predation water treatments (PC3, P = 0.6830) (Tukey–Kramer multiple comparisons).

Species Specificity of Cues

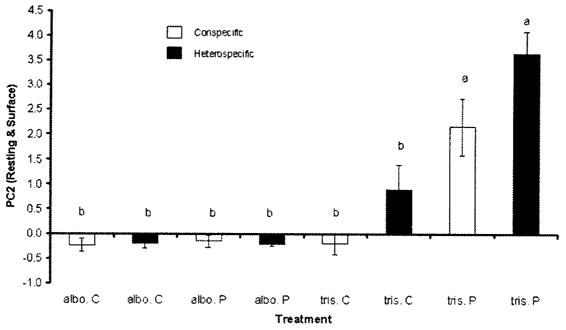

There was a high positive correlation between resting and surface, and browsing was highly correlated with wall and bottom (Table 5). Four of the eight principal components summarized 93% of the variation and had Eigen values >1.0. The fifth PC was less than one-half of the fourth PC (Table 6). PC2 quantifies resting in surface versus other behaviors. Higher scores on PC2 are associated with more frequent resting in the surface (Table 7). Because resting and surface are the least dangerous activity and position with respect predation (Juliano and Reminger 1992), and because PCs involving resting and surface have been shown to be affected by predator treatments (Juliano and Gravel 2002; this study) we concentrated our analysis on PC2, by using ANOVA. There was a significant test species (A. albopictus and O. triseriatus) and treatment (control and predation) interaction, indicating that the change in behavior between control and predation water differed significantly between the two test species (Table 8). But there was no three-way interaction (test species, treatment, and preparation) effect, which indicates that the species of prey (conspecific or heterospecific) fed to the T. rutilus did not alter the response of the test species to water-borne cues from predation (Table 8). O. triseriatus shows a high frequency of low-risk behavior (resting and surface), even in predation water prepared by feeding A. albopictus to T. rutilus (Fig. 3). In contrast, A. albopictus did not alter its behavior in response to any of the treatments (Fig. 3).

Table 5.

Correlation’s of activities and positions for the species specificity experiment

| Thrashing | Browsing | Filtering | Surface | Bottom | Wall | Middle | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resting | 8 | −9 | 15 | 99 | −2 | −7 | 11 |

| Thrashing | 26 | −10 | 5 | 58 | 17 | 25 | |

| Browsing | 25 | −8 | 65 | 95 | 25 | ||

| Filtering | 19 | 25 | 21 | 66 | |||

| Surface | −3 | −5 | 9 | ||||

| Bottom | 40 | 47 | |||||

| Wall | 14 |

All data pooled. Boldfaced numbers represent significant (P < 0.05) correlations.

Table 6.

Principal component analysis for the species specificity experiment

| PC1 | PC2 | PC3 | PC4 | PC5 | PC6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eigen value | 2.89 | 2.11 | 1.28 | 1.13 | 0.31 | 0.24 |

| Proportion of variance | 0.36 | 0.26 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| Cumulative proportion of variance | 0.36 | 0.63 | 0.79 | 0.93 | 0.97 | 0.99 |

Principal components in bold are those with Eigen values >1 that were retained for behavior analysis.

Table 7.

Varimax rotated factor pattern for the species specificity experiment

| Response Variables | PC1 | PC2 | PC3 | PC4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resting | −5 | 99 | 6 | 4 |

| Thrashing | 7 | 6 | −5 | 94 |

| Browsing | 95 | −6 | 15 | 24 |

| Filtering | 18 | 13 | 91 | −15 |

| Surface | −3 | 100 | 8 | 0 |

| Bottom | 43 | −6 | 33 | 73 |

| Wall | 98 | −2 | 6 | 6 |

| Middle | 3 | 3 | 88 | 32 |

| Interpretation | Browsing, bottom, wall vs. other behaviors | Resting, surface vs. other behaviors | Filtering, bottom vs. other behaviors | Thrashing, bottom vs. other behaviors |

Values >0.4 are listed in boldface; they indicate strong loadings on each principal component.

Table 8.

ANOVA table for PC2 (resting, surface) of the species specificity experiment

| Source | df | F | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Test Species | 1 | 43.89 | <0.0001 |

| Treatment | 1 | 25.63 | <0.0001 |

| Preparation | 1 | 4.31 | 0.0525 |

| Test * treatment | 1 | 26.83 | <0.0001 |

| Test * preparation | 1 | 6.84 | 0.0175 |

| Treatment * preparation | 1 | 0.07 | 0.7944 |

| Test species * treatment* Preparation | 1 | 0.22 | 0.6427 |

| Error | 18 |

Test species are A. albopictus and O. triseriatus. Treatments are control and predation waters.

Preparation indicates whether test water was conditioned using conspecifies or heterospecifies.

Fig. 3.

Species specificity of cues. PC2 (resting at the surface) (mean ± SE) for all the treatments. albo, A. albopictus; tris, O. triseriatus; C, control; P, predation; conspecific, water prepared by adding conspecific larvae; heterospecific, water prepared by adding heterospecific larvae (either O. triseriatus or A. albopictus). Means marked by the same letter are not significantly different (Tukey–Kramer multiple comparisons).

Discussion

Aedes albopictus did not modify behavior in response to water-borne cues from predation by T. rutilus, whereas O. triseriatus changed its behavior, increasing the frequency of low-risk responses to water-borne cues of predation risk. Ochlerotatus triseriatus spent more time resting on the surface in the presence of water-borne cues to predation risk (Fig. 3). Resting on the surface in the presence of predation is the least risky behavior (Juliano and Reminger 1992). In the absence of water-borne cues to predation risk, both O. triseriatus and A. albopictus spend considerable time browsing along the wall. However, A. albopictus does not reduce the risky behavior of thrashing, even in the presence of water-borne cues to predation (Fig. 2). O. triseriatus alters its behavior in response to water-borne cues from predation on conspecifics and on A. albopictus (Fig. 3). Its response of increased resting at the surface in predation water is thus not species specific to the prey. Its response may thus be a general reaction to cues from any aquatic predator, or alternatively to cues emanating directly from T. rutilus.

The absence of a behavioral response in A. albopictus may suggest that A. albopictus is more vulnerable to predation than O. triseriatus. This suggestion is consistent with Campos and Lounibos (2000) who showed that A. albopictus is preferred by T. rutilus over other prey. Instantaneous risk of mortality due to predation is probably the main variable affected by behavioral changes, but there may be other impacts of a predator such as T. rutilus that may complicate assessment of which species is more vulnerable to this predator. O. triseriatus seems to have a lower growth rate in the presence of T. rutilus compared with O. triseriatus that grow in the absence of the T. rutilus (Lounibos et al. 1993). This reduced growth is observed even though mortality caused by the predator reduces density of O. triseriatus, and should therefore reduce intraspecific competition. It seems likely that low-risk behaviors of resting at the surface have a cost for O. triseriatus, probably due to reduced foraging (but see Hechtel and Juliano 1997), that may have an impact on its growth rate. Also, it has been shown that under field conditions A. albopictus is a superior competitor to O. triseriatus even in the presence of T. rutilus (Lounibos et al. 2001). The disadvantage of O. triseriatus could be, in part, the result of O. triseriatus’s reducing its activity levels in the presence of predation risk by resting and staying at the surface. In contrast, A. albopictus does not adopt these low-risk behaviors and can therefore realize greater feeding and growth rates, and perhaps greater competitive ability. In the absence of predation, growth and development of A. albopictus are more rapid than those of O. triseriatus (Ho et al. 1989, Livdahl and Willey 1991, Novak et al. 1993), and this slower development may result in the duration of exposure to predation for larval O. triseriatus being longer than the corresponding period for A. albopictus. Cumulative mortality due to predation is a product of both the instantaneous rate of mortality (presumably lower in O. triseriatus) and the duration of exposure (presumably lower for A. albopictus), so that prediction of which species will have greater cumulative death rate will be difficult.

Ochlerotatus triseriatus that we used for this experiment were collected from Normal where they seldom encounter T. rutilus (Juliano 1996, Juliano and Gravel 2002). Despite this rarity of predation, individuals from this population still alter their behavior in the presence of water-borne cues from this predator (Juliano and Gravel 2002), which suggests that these behavioral responses are an ancestral character for O. triseriatus. Juliano and Gravel (2002) showed that when subject to consistent predation by T. rutilus in the laboratory, O. triseriatus shifted from this facultative response to a constitutive pattern of low movement and resting at the surface. Thus, the facultative response shown by O. triseriatus may be most advantageous in situations when the predator is only sometimes present. One interpretation of the absence of any shift in A. albopictus, and its generally high level of movement, particularly thrashing (Fig. 2) and browsing (Fig. 1) could therefore be that it has little history of exposure to Toxorhynchites predation, and is thus poorly adapted for encounters with this predator. Although in its native range A. albopictus occurs in sympatry with several species of Toxorhynchites (Hawley 1988) encounters with this group of predators may be rare because of oviposition choices of different-sized containers or of different habitats that may not be preferred by Toxorhynchites spp. (Lounibos et al. 2001, Sunahara et al. 2002). Furthermore, North American A. albopictus are believed to have originated in temperate Japan (Hawley et al. 1987), and although Toxorhynchites occurs in Japan (Collins and Blackwell 2000), this is near its northernmost range limit, hence it may be relatively less common than in tropical Asia. Hence, A. albopictus may never have undergone strong selection for behavioral reductions of predation risk. However, the absence of this behavioral response to T. rutilus in A. albopictus could be explained in several other ways. It remains possible that A. albopictus are not using the same kind of cues as O. triseriatus to detect predation risk. For example, A. albopictus may respond to the visual presence of a predator, or to the combination of visual and water-borne cues. Alternatively, behavioral responses of mosquitoes to predators may be highly predator specific, and A. albopictus may not respond to T. rutilus because of its lack of evolutionary history with this predator species that is native to North America. In this context, it is important to determine whether A. albopictus shows behavioral responses to Toxorhynchites species from its native Asia.

Acknowledgments

We thank K. S. Costanzo, T. L. Manning, S. Rokosic, R. L. Escher, K. Damal, and L. P. Lounibos for help with conducting these experiments; Parklands Foundation and Florida Medical Entomology Laboratory for access to field sites; and L. P. Lounibos and an anonymous referee for helpful comments on the manuscript. This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01-AI44793 and the Illinois State University Beta Lambda chapter of Phi Sigma.

References

- Campos RE, Lounibos LP. Natural prey digestion times of Toxorhynchites rutilus (Diptera: Culicidae) in southern Florida. Ann Entomol Soc Am. 2000;93:1280–1287. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/37.3.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins LE, Blackwell A. The biology of Toxorhynchites mosquitoes and their potential as biocontrol agents. Biocontrol News Info. 2000;21:105N–116N. [Google Scholar]

- Grill CP, Juliano SA. Predicting interactions based on behavior: predation and competition in container-dwelling mosquitoes. J Anim Ecol. 1996;65:63–76. [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher L, Stepansky EJ. A step by step approach to using SAS system for univariate and multivariate analyses. SAS Institute; Cary, NC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hawley WA, Reiter P, Copeland RS, Pumpuni CB, Craig GB., Jr Aedes albopictus in North America: probable introduction in used tires from northern Asia. Science (Wash DC) 1987;236:1114–1116. doi: 10.1126/science.3576225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawley WA. The biology of Aedes albopictus. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 1988;4(Suppl):1–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hechtel LJ, Juliano SA. Effects of a predator on prey metamorphosis: plastic responses by prey or selective mortality? Ecology. 1997;78:838–851. [Google Scholar]

- Ho BC, Ewert A, Chew L. Interspecific competition among Aedes aegypti, Ae. albopictus and Ae. triseriatus (Diptera: Culicidae): larval development in mixed cultures. J Med Entomol. 1989;26:615–623. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/26.6.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juliano SA, Hechtel LJ, Waters JR. Behavior and risk of predation in larval tree hole mosquitoes: effects of hunger and population history of predation. Oikos. 1993;68:229–241. [Google Scholar]

- Juliano SA. Geographic variation in Aedes triseriatus (Diptera: Culicidae): temperature-dependent effects of a predator on survival of larvae. Environ Entomol. 1996;25:624–631. [Google Scholar]

- Juliano SA, Gravel ME. Predation and the evolution of prey behavior: an experiment with tree hole mosquitoes. Behav Ecol. 2002;13:301–311. [Google Scholar]

- Juliano SA, Reminger L. The relationship between vulnerability to predation and behavior of larval treehole mosquitoes: geographic and ontogenetic differences. Oikos. 1992;63:465–467. [Google Scholar]

- Livdahl TL, Willey MS. Prospects for invasion: competition between Aedes albopictus and native Aedes triseriatus. Science (Wash DC) 1991;253:189–191. doi: 10.1126/science.1853204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lounibos LP, Nishimura N, Escher RL. Fitness of a tree hole mosquito: influences of food type and predation. Oikos. 1993;66:114–118. [Google Scholar]

- Lounibos LP, O’Meara GF, Escher RL, Nishimura N, Cutwa M, Nelson T, Campos RE, Juliano SA. Testing predicted competitive displacement of native Aedes by the invasive Asian tiger mosquito Aedes albopictus in Florida, USA. Biol Invas. 2001;3:151–166. [Google Scholar]

- Martin P, Bateson P. Measuring behavior: an introductory guide. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Moore CG. Aedes albopictus in the United States: current status and prospects for further spread. J Am Mosq Contr Assoc. 1999;15:221–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak MG, Higley LG, Christianssen CA, Rowley WA. Evaluating larval competition between Aedes albopictus and Aedes triseriatus (Diptera: Culicidae) through replacement series experiments. Environ Entomol. 1993;22:311–318. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio Y, Rodriguez D, Machado-Allison CE, Leon JA. Algunos aspectos del comportamiento de Toxorhynchites theobaldi (Diptera: Culicidae) Acta Cient Venez. 1980;31:345–351. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio Y, Leon JA, Rodriguez DJ, Machado-Allison CE. Tacticas depredatoria de Toxorhynchites theobaldi (Diptera: Culicidae) Acta Cient Venez. 1981;32:523–548. [Google Scholar]

- Russo R. Comparison of predatory behavior in five species of Toxorhynchites (Diptera: Culicidae) Ann Entomol Soc Am. 1986;79:715–722. [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute. SAS/STAT user’s guide, version 6. 4. 1 and 2. SAS Institute; Cary, NC: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Scheiner SM. MANOVA. Multiple response variables and multi species interactions. In: Scheiner SM, Gurevitch J, editors. Design and analysis of ecological experiments. 2. Oxford University Press; Oxford, England: 2001. pp. 99–133. [Google Scholar]

- Steffan WA, Evenhuis NL. Biology of Toxorhynchites. Annu Rev Entomol. 1981;26:159–181. [Google Scholar]

- Sunahara T, Ishizaka K, Mogi M. Habitat size: a factor determining the opportunity for encounters between mosquito larvae and aquatic predators. J Vect Ecol. 2002;27:8–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng HJ, Apperson CS. Development and survival of immature Aedes albopictus and Aedes triseriatus (Diptera: Culicidae) in the laboratory: effects of density, food, and competition on response to temperature. J Med Entomol. 2000;37:40–52. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-37.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]