Abstract

The synthesis of phosphatidylcholine (PtdCho), the major phospholipid in mammalian cells, is regulated by the CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase (CCT). Loss of the CCTβ2 isoform expression in mice results in gonadal dysfunction. CCTβ2−/− females exhibit ovarian tissue disorganization with progressive loss of follicle formation and oocyte maturation. Ultrastructure revealed a disrupted association between ova and granulosa cells and disorganized Golgi apparati in oocytes of CCTβ2−/− mice. Probucol is a cholesterol-lowering agent that stimulates the uptake and retention of lipids carried by lipoproteins in peripheral tissues. Probucol therapy significantly lowered both serum cholesterol and PtdCho levels. Probucol therapy increased fertility in the CCTβ2−/− females 100%, although it did not completely correct the phenotype, the morphological abnormalities in the knockout ovaries or itself stimulate CCT activity directly. These data indicated that a deficiency in de novo PtdCho synthesis could be complemented by altering the metabolism of serum lipoproteins, an alternative source of cellular phospholipid.

Keywords: Phosphatidylcholine, Cytidylyltransferase, Gene knockout, Lipoprotein, Ovary, Fertility

1. Introduction

Phosphatidylcholine (PtdCho) is a major component of biological membranes in mammals and the CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase (CCT) is a key rate-controlling step in the CDP-choline biosynthetic pathway leading to PtdCho [1]. There are two genes encoding the mammalian CCTs: the Pcyt1a encoding the murine CCTα protein, and the Pcyt1b encoding the murine CCTβ2 and β3 proteins [2]. The CCTα isoform is the most abundant and ubiquitously expressed of the isoforms. The absence of CCTα expression in mice is lethal early in embryogenesis and CCTα homozygous null (CCTα−/−) embryos arrest at the morula stage (E3.5) prior to implantation [3]. The membrane phospholipid synthesis associated with the first few cell divisions after fertilization of the CCTα knockout embryo is supported by CCTβ2 expression which is high in oocytes [4]. These data indicate that the CCT isoforms are at least partially redundant in biochemical function. The tissue-specific knockouts of CCTα in mouse macrophages [5], liver [6] and lung [7] reveal that CCTα expression is not required to support the proliferation and differentiation of these lineages. However, the CCTα−/− macrophages fail to support the increased PtdCho synthesis necessary for an adaptive response to cholesterol loading [5], the CCTα−/− livers are deficient in lipoprotein export [6], and the CCTα−/− lung epithelia are defective in surfactant production and secretion [7]. These data suggest that CCTα-mediated PtdCho synthesis is important for specific cellular functions.

CCTβ2 is a minor isoform but is significantly expressed in adult gonads and brain [4]. CCTβ2−/− mice are viable and the most notable phenotype of CCTβ2 knockout mice is gonad degeneration and reproductive deficiency, suggesting either a loss of the response to hormonal stimulation, or a failure in paracrine communication between gonadal cells. A large percentage of the female CCTβ2−/− mice have compromised ovarian follicle development leading to sterility. Male CCTβ2 knockout mice have progressive multifocal testicular degeneration resulting in eventual reduced fertility [4]. A similar phenotype is associated with inactivation of the Cct1 gene in Drosophila melanogaster. Partial inactivation reveals that the Cct1 gene is essential for oogenesis and ovarian morphogenesis [8], whereas null mutations are embryonic lethal [9]. The Drosophila Cct1 gene is expressed at high levels in ovarian follicle cells, and Cct1−/− cells show evidence of defective endosomal trafficking, leading to a reduction in epidermal growth factor receptor signaling [9]. Altogether, these data suggest that reduced de novo PtdCho synthesis limits the processes underlying gonadal maturation.

Ovaries are capable of de novo steroidogenesis, but the vast majority of the steroids are synthesized from cholesterol delivered to the ovaries in mice by circulating high density lipoprotein (HDL) [10–12]. The scavenger receptor, class B, type I (SR-BI) is the major route for the delivery of HDL-cholesterol to the steroidogenic metabolic pathway [13] and plasma HDL is the primary cholesterol source for rodent steroidogenic tissues [14]. Mice with homozygous null mutations in the gene for the SR-BI have dysfunctional oocytes and are infertile [15]. Probucol promotes the uptake and retention of HDL-cholesterol, thereby lowering the serum cholesterol levels [10,16–19]. Administration of probucol restores fertility in the SR-B1 knockout females [20], supporting the concept that HDL uptake and utilization is a determining factor in female fertility. Lipoproteins are most often considered as mediators of cholesterol transport, but PtdCho is another major component of HDL. We found that probucol lowered both serum cholesterol and PtdCho, and increased fertility of the knockout animals by 100%. The CCTβ2−/− female mouse model revealed that deficient de novo PtdCho synthesis could be complemented by altering the metabolism of serum HDL, an alternative source of cellular phospholipid.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Mouse model

Derivation of the CCTβ2−/− mice which were homozygous null mutants of the Pcyt1b gene was described previously [4]. Mice were maintained in a temperature-controlled (20°C) room with a 12-h light/dark cycle, with regular chow and water provided ad libitum. 129/Sv × C57BL/6J mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor Maine) were used as control wild-type male mice for mating to determine fertility. CCTβ2+/+ littermate mice were used as wild-type female controls. In the first experiment, animals were 8 weeks old and were fed either regular chow or chow containing probucol at 0.5% (weight/weight) [20] ad libitum for 16 weeks. During the last 4 weeks on the diets, knockout and wild-type females were mated with wild-type males. In the second experiment, pregnant dams at day E19.5 were either maintained on a chow diet or put on a chow diet containing probucol at 2% (weight/weight), and both dams and pups were maintained on the same diets until weaning at 3–4 weeks after birth. At weaning, pups were genotyped and female CCTβ2−/− mice were maintained on the same diets for 12 more weeks. During the last 4 weeks on the diets, animals were mated with wild-type males to determine fertility. Fertility was scored as positive if litters were born or the females were pregnant after 4 weeks with the male animals. This time period was selected because females that did not become pregnant in this 4 week window never became pregnant. Tissues and blood were obtained from euthanized animals at the end of the 4 week period. All procedures in this study were approved by the institutional animal care and use committee.

2.2. Serum hormone and lipid determinations

Serum (70 μl) from wild-type and knockout mice was fractionated using a 2.4 ml Superose 6 column eluted with 4.2 ml of PBS to separate VLDL, LDL and HDL [21]. Fractions of 50 μl were collected and total cholesterol (cholesterol plus cholesterol ester) was quantified by adding 150 μl of reagent (Bachem #80015) to each fraction and reading the optical density at 490 nm according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The lipids were quantified using the Iatroscan (Mitsubishi Kagaku Iatron) after fractionation on silica gel rods developed in hexane:ether:acetic acid (80/20/1). This system separated cholesterol, fatty acid, triglyceride and cholesterol ester. PtdCho was measured using the same system with chloroform:methanol:acetic acid:water as the solvent system. The amount of lipid present was determined using standard curves prepared with known amounts of individual lipid standards.

2.3. Electron microscopy

Ovaries were fixed in cacodylate-buffered 2.5% glutaraldehyde, post-fixed in osmium tetroxide, dehydrated in graded series of alcohols, and embedded in Spurr low-viscosity embedding medium (Ladd Research Industries, Burlington VT). Ultrathin sections were cut with a diamond knife on a Sorvall MT 6000 ultramicrotome. The sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and then examined in a Phillips EM 301 electron microscope at 80 kV.

2.4. Measurement of PtdCho synthesis

Y-1 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection and cultured as recommended. Cells were incubated for 6 hours in the presence of 5 μCi/ml [3H]choline chloride (American Radiolabel Chemicals) in the absence or presence of added probucol at 5, 10, 20, 40 and 80 μM final concentration. At the end of the labeling period, culture dishes were transferred to ice, the cells were washed twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline, and chloroform:methanol (1:2) was added to the dishes to begin lipid extraction. The cell samples were collected and the lipid extraction was completed essentially by the method of Bligh and Dyer [22]. The organic phase was quantified by scintillation counting and normalized to protein content of the samples. Enzymatic assays were performed using recombinant rodent CCTα that was expressed in baculovirus [23] and purified by nickel-affinity chromatography. DioleylPtdCho:oleic acid (DOPC:OA) vesicles (8:2) were used to activate the enzyme in the assay which was performed essentially as described [24] and probucol was added to the lipid vesicle mixture at a molar ratio of DOPC:OA:probucol (7:2:1). Assays (40 μl final volume) were started by addition of 0.1 μCi [14C]phosphocholine (American Radiolabel Chemicals) and stopped by addition of 50 mM Na2EDTA (final concentration) after a 30-minute incubation at 37°C. The conversion of substrate to [14C]CDP-choline product was quantified following thin-layer chromatography in methanol:0.1M NaCl:NH4OH (10:10:1).

2.5. SR-B1 expression analysis

Ovaries were placed in 4% paraformaldehyde fixative overnight. After fixation, the ovaries were stored in 70% ethanol at 4°C until processed. Tissues were dehydrated in increasing concentrations of ethanol, embedded in paraffin wax, and sectioned at a thickness of 5 μm. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin or were processed for immunohistochemical analysis with antibodies to mouse SR-B1 (a gift of Monty Krieger, Massachusetts Institute of Technology) and used at a dilution of 1:100. Total RNA was isolated from ovaries using TRIZOL (Invitrogen)after prior incubation in RNAlater (Ambion); contaminating genomic DNA was removed by digestion with DNase I, and aliquots were stored as an ethanol precipitate at −20°C. cDNA was prepared from RNA by reverse transcription using SuperScript II RNase H− Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen) and random primers. Primers and probes for real-time qRT-PCR were designed using Primer Express® Software (Version 2.0; Applied Biosystems) and are listed in Table 1. Real-time qRT-PCR was carried out using the 7300 Real Time PCR System and 7300 System SDS software (Version 1.2.3; Applied Biosystems). The Taqman Rodent GAPDH Control Reagent (Applied Biosystems) was the source of the primers and probes for quantifying the control Gapdh mRNA. The collected data were analyzed using the CT method (35); the amount of target RNA was normalized to the endogenous Actb2 reference and related to the amount of target RNA at 0 hour.

Table 1.

Sequences of real-time qRT-PCR primers and probes (5′–3′)

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer | Probe |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ldlr | AGGCTGTGGGCTCCATAGG | GCGGTCCAGGGTCATCTTC | 6FAM-TATCTGCTCTTCACCAACCGCCA-TAMRA |

| Srb1 | CAGACAAAAGGTCAACATCACCTT | AATGGAGGCTGCGGTTCTC | 6FAM-AATGACAACGACACCGTGTCCT-TAMRA |

| Pemt | GGCATCTGCATCCTGCTTTT | TTGGGCTGGCTCATCATAGC | 6FAM-CTCCGCTCCCACTGCTTCACAC-TAMRA |

2.6. Statistical analysis

Either the two-tailed t-test for significances between means or the Fisher exact test were used to compare results between mouse groups as indicated in the individual figures. The statistical analysis package included in GraphPad Prism software was used to perform the calculations.

3. Results

3.1. Ovary ultrastructure in CCTβ2−/− mice

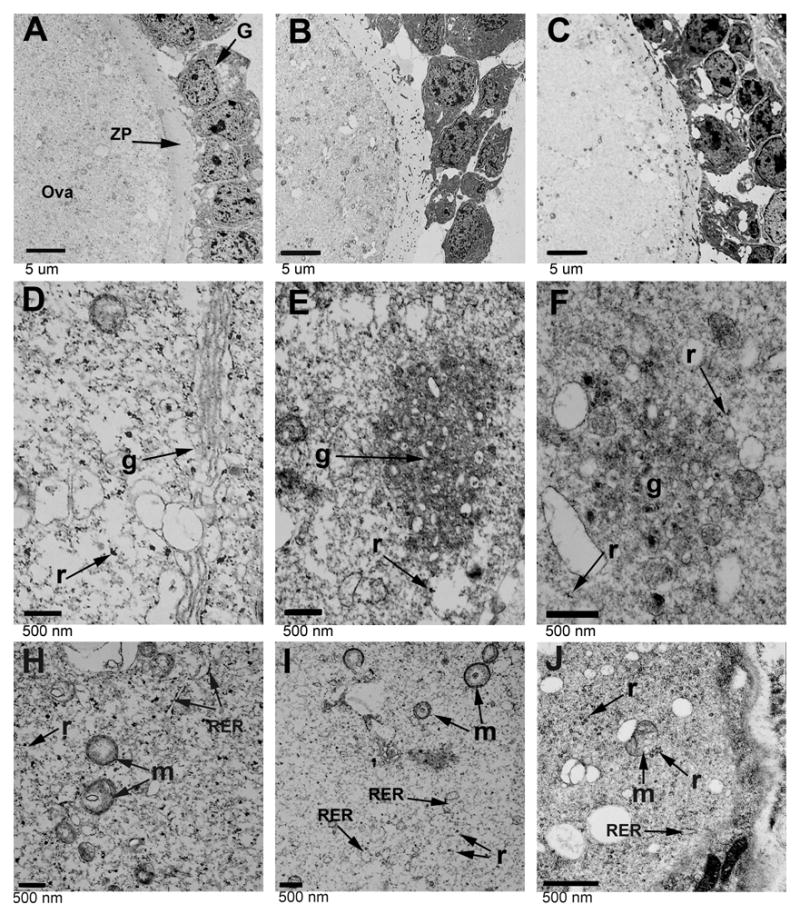

CCTβ2 is highly expressed in oocytes and at a somewhat lower level in granulosa cells, and loss of CCTβ2 expression results in disorganization of the ovary and diminished follicle development [4]. Examination of the ovary morphology by electron microscopy showed structural alterations consistent with dysfunctional intracellular membrane biogenesis in oocytes coupled with the failure of the oocytes to effectively interact with the granulosa cells (Fig. 1). Ovaries from CCTβ2−/− animals that had some evidence of follicle development were examined and revealed a reduced association between the granulosa cells and detachment from the ova, with fewer junctions between adjacent granulosa cells compared to wild-type tissue (Figs. 1A and 1B). Infiltration of granulosa microvilli through the zona pellucida surrounding the ova, which is mediated by the secretion of paracrine factors from the granulosa cells [25], was also reduced. There was a reduction in the intracellular vesicle accumulation at the surface of the ova and within the granulosa cells (Figs. 1A and 1B). Also, the subcellular membrane organization in the ova was clearly disrupted. In wild-type ova, the Golgi complex was normally near the outer membrane surface, as evidenced by its multilamellar structure and the proximity of large secretory granules (Fig. 1D). In the knockout ova, the normal Golgi structure was missing and was replaced with a compact bundle of membranes with little evidence of an organized layered structure (Fig. 1E). The associated vesicles were smaller and interspersed within the complex. The cytoplasm of the wild-type ova was packed with rough endoplasmic reticulum (Fig. 1H), whereas the knockout ova had a paucity of membraneous structures in the cytoplasm coupled with a greater number of free ribosomes (Fig. 1I). These observations suggested that the intracellular membrane organization was defective in CCTβ2−/− oocytes.

Fig. 1.

Ovary structure in CCTβ2−/− females. The ultrastructure of ova and granulosa cells in normal females (Panels A, D and H), CCTβ2−/− females (Panels B, E and I), and probucol-treated CCTβ2−/− females (Panels C, F and J) were evaluated by transmission electron microscopy. G, granulose cells; ZP, zona pellucida; g, Golgi apparatus; r, ribosomes; RER, rough endoplasmic reticulum; and m, mitochondria. Results shown are representative of 3 mice in each group.

3.2. Increased fertility in probucol-treated CCTβ2−/− females

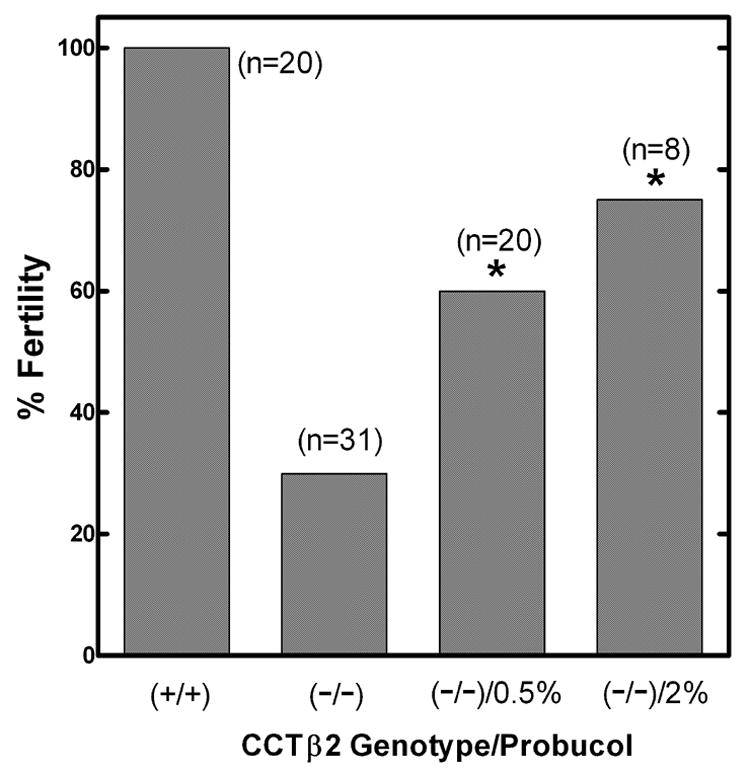

The CCTβ2 knockout females exhibit reduced fertility due to a low frequency of mature follicle development [4]. Backcrossing the CCTβ2−/− animals onto the C57BL6/J strain for eight generations did not change the low fertility phenotype of the homozygous knockouts, indicating that the reproductive defect and the incomplete penetrance of the phenotype was not strain dependent. Probucol is an established cholesterol lowering agent that functions by stimulating the uptake and retention of lipoprotein-associated lipids by peripheral tissues [10]. We tested whether probucol could overcome the infertility of the knockout females using two treatment regimens. A 0.5% probucol supplement doubled the number of fertile knockout females (Fig. 2). In a second experiment to determine if the knockout phenotype was further correctable, the probucol dose was increased to 2% and mice were supplemented with the drug during gestational and neonatal development, as well as through sexual maturation and mating. The results from this experiment showed that 75% of the females were fertile compared to 30% of the CCTβ2−/− non-medicated controls (Fig. 2). These data showed that probucol therapy increased the fertility of CCTβ2−/− females. Whereas probucol therapy increased the proportion of CCTβ2−/− females with ovaries having mature follicles and with demonstrated fertility, we were unable to conclude that probucol normalized the ovary ultrastructure in treated CCTβ2−/− mice (Figs. 1C, 1F and 1J).

Fig. 2.

Fertility in CCTβ2−/− mice. The fertility of wild-type females (n=20) was compared to untreated CCTβ2−/− females (n=31), or CCTβ2−/− females supplemented with either 0.5% (n = 20) or 2% (n = 8) probucol and the number of fertile females (either pregnant or bearing litters following mating with wild-type males) was scored. There was a significant difference between the untreated CCTβ2−/− controls and the 0.5% or 2% groups (*, p < 0.05) using Fisher’s exact test. The difference between the 0.5% and 2% treatment groups was not significant.

3.3. Steroid hormone levels

The increased fertility of the CCTβ2-deficient animals on a probucol diet raised the question of whether an increase in steroid synthesis accounted for the effect. Gonads and adrenal glands are the major producers of the steroid hormones from cholesterol, and reduced steroidogenesis would possibly lead to elevated levels of follicle-stimulating hormone and leutininzing hormone as observed in older CCTβ2-deficient mice [4]. Progesterone and estradiol levels in the CCTβ2-deficient mice were compared to the values from wild-type littermate controls (Table 1). Progesterone levels were comparable in the virgin state between the two genotypes. Progesterone increased significantly in the pregnant wild-type mice, from 6.48 ng/ml in virgin females to 31.55 ng/ml. Progesterone also increased in the pregnant knockout mice to 26.8 ng/ml, and was low in virgin mice (5.61 ng/ml). Treatment of CCTβ2−/− mice with probucol reduced the progesterone levels in pregnant mice to 9.88 ng/ml, whereas the levels were unchanged in non-pregnant mice (8.68 ng/ml). Estradiol levels were similar in virgin and pregnant mice of both genotypes and were measured at 1000-fold lower levels compared to progesterone. Wild-type virgin females had levels of 24.96 pg/ml compared to 24.81 pg/ml during pregnancy. The CCTβ2−/− virgin females had 27.49 pg/ml compared to 26.79 pg/ml in the pregnant dams. Probucol therapy did not increase the estradiol level in virgin CCTβ2−/− females (27.41 pg/ml). None of the values obtained from the knockout mice were significantly different (p>0.05) when compared with the corresponding values from virgin or pregnant wild-type animals. These data indicated that conversion of cholesterol to steroidogenic hormones was not deficient in the CCTβ2−/− knockout animals, and that the probucol effect on fertility could not be ascribed to increased cholesterol conversion to steroid hormones.

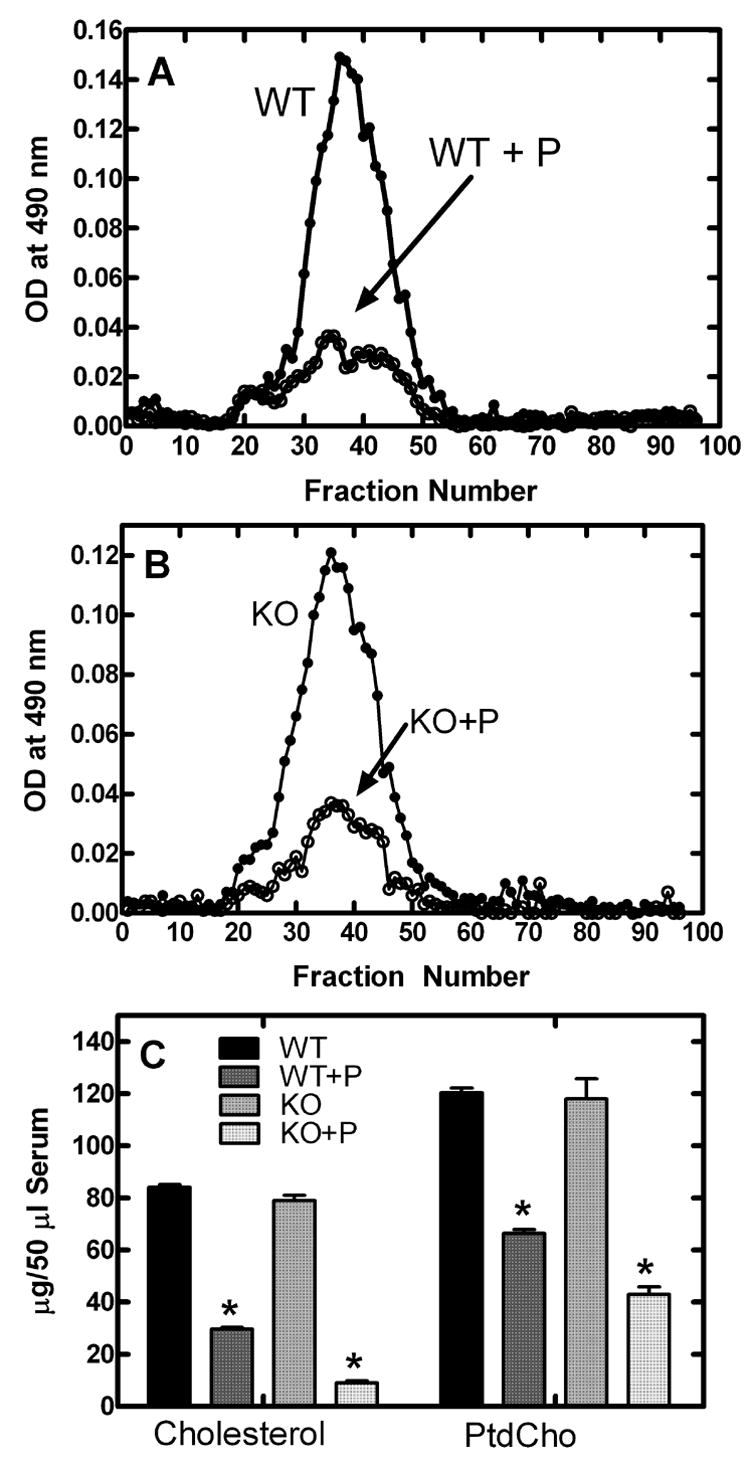

3.4. Probucol reduces serum PtdCho and increases ovary PtdCho

The serum cholesterol-lowering effect of probucol is well-documented [10,20] and both wild-type and CCTβ2−/− mice treated with 2% probucol exhibited the expected dramatic decrease in HDL-cholesterol as determined by gel filtration chromatography (Fig. 3A and 3B). Quantification of the serum total cholesterol levels showed that probucol therapy resulted in almost 90% reduction in the knockout animals. Significantly, probucol also induced a 60–70% depletion of PtdCho in the serum from knockout animals (Fig. 3C), consistent with the decrease in serum HDL and indicating enhanced uptake and/or retention of HDL-lipid in peripheral tissues in the treated animals. Probucol therapy reduced total cholesterol from 84.2 to 29.7 μg/50 μl serum and reduced PtdCho from 120.4 to 66.4 μg/50 μl serum in the wild-type mice. These data illustrated that the HDL-lowering effect expected of probucol therapy was reproduced in our experiments and that, in addition to lowering serum cholesterol, the alteration in HDL metabolism by probucol led to a decrease in circulating PtdCho levels.

Fig. 3.

Serum PtdCho and cholesterol levels in probucol-treated animals. A, Superose 6B fractionation of serum from probucol-treated (○) and untreated (●) wild-type animals; B, fractionation of serum from probucol-treated (○) and untreated (●) CCTβ2−/− animals; C, Levels of total cholesterol (free plus cholesterol ester) and PtdCho in serum from CCTβ2−/− mice treated with 2% probucol compared to untreated CCTβ2−/− mice and wild-type untreated controls. *indicates significance of p<0.05 using the students t-test when comparing treated with untreated of the same genotype and n = 15 for each group.

Probucol therapy had a measurable impact on the PtdCho and cholesterol contents of wild-type and knockout ovaries (Table 3). Control wild-type ovaries possessed 18.9 μg/mg wet weight of PtdCho, for a total of 107.3 μg per gonad, which decreased to 78.4 μg per gonad following 2% probucol. The treatment was accompanied by a 25% decrease in ovary size, from and average 5.7 mg (n = 5) to 4.3 mg (n = 5) per gonad. On the other hand, the PtdCho content and size of the knockout ovaries increased following probucol therapy, from 76.5 to 110.3 μg PtdCho per gonad, and enlargement from 5.4 (n = 7) to 7.0 (n = 5) mg each. Interestingly, the PtdCho per mg wet weight did not change significantly following probucol treatment of either genotype (Table 3). The ovarian cholesterol level in the knockout animals was also maintained after probucol, at about 11 μg/mg wet weight, while the cholesterol decreased substantially in the wild-type, both in terms of wet weight and per gonad (Table 3). These data indicated that the lipid metabolic adjustment in response to probucol enhanced the size and PtdCho mass of the CCTβ2−/− ovaries, yet did not have the same effect in the wild-type animals. c

Table 3.

Phosphatidylcholine and cholesterol content of wild-type and CCTβ2−/− ovaries.

| Genotype | PtdCho μg/gonad | PtdCho μg/mg weight | CholesterolA μg/gonad | CholesterolA μg/mg weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-Type | 107.29 ± 3.5 (n=3) | 18.90 ± 0.62 (n=3) | 116.82 ± 7.79 (n=3) | 20.58 ± 1.51 (n=3) |

| Wild-Type + Probucol | 78.45 ± 1.57** (n=3) | 18.24 ± 0.36 (n=3) | 47.38 ± 0.86*** (n=3) | 10.99 ± 0.17** (n=3) |

| CCTβ2−/− | 76.51 ± 3.33 (n=3) | 14.19 ± 0.35 (n=3) | 57.90 ± 3.41 (n=3) | 10.67 ± 0.57 (n=3) |

| CCTβ2−/− + Probucol | 110.28 ± 4.2** (n=3) | 15.88 ± 0.60 (n=3) | 79.63 ± 5.01* (n=3) | 11.45 ± 0.59 (n=3) |

Lipid masses were measured following thin-layer fractionation as described under Materials and Methods.

indicates cholesterol plus cholesterol ester. Data analysis using the students t-test showed a significant difference for PtdCho per gonad between wild-type treated vs. untreated ovaries (**p<0.01); between knockout untreated and treated ovaries (**p<0.01); for cholesterol per gonad between wild-type treated and untreated ovaries (***p<0.001); between knockout treated vs. untreated ovaries (*p<0.05); and cholesterol per mg weight, between wild-type treated and untreated ovaries (**p<0.01).

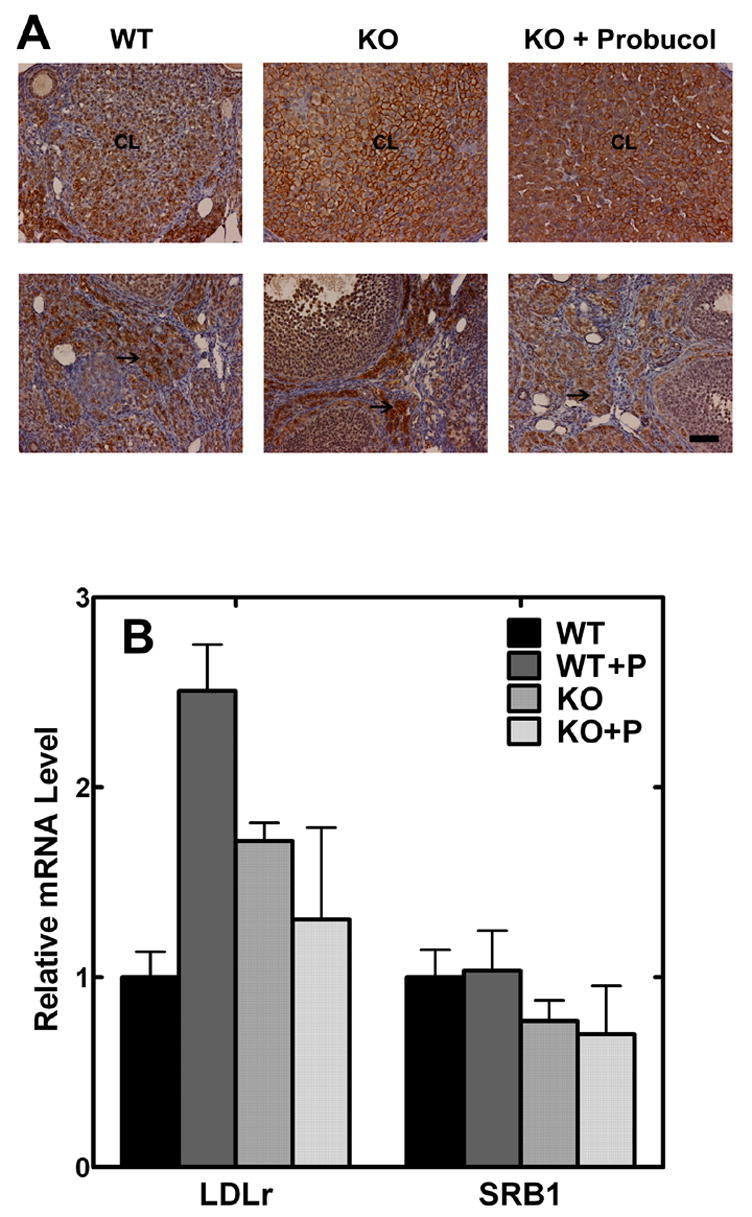

3.5. Probucol does not affect SR-B1 expression

Probucol did not alter the pattern or magnitude of SR-B1 expression in the ovaries. The distribution of SR-B1 was determined in wild-type and knockout ovaries using immunohistocytochemistry with an anti-SR-B1 antibody. The SR-B1 was expressed in the corpus lutei and interstitial cells as expected in the wild-type and, despite the disorganization of the knockout ovaries, the staining was apparent in these cell types as well (Fig. 4). There was no apparent difference in the intensity or distribution of SR-B1 in the presence or absence of probucol (Fig. 4). We also measured SR-B1 expression and LDL receptor expression in the treated and untreated ovaries. While probucol did not have any effect on SR-B1 expression either in wild-type or CCTB2-null ovaries, probucol therapy increased expression of the LDL receptor in wild-type, but not in knockout tissues. These results were consistent with the previous report that probucol did not alter SR-B1 expression in the ovary [26] and did not explain correction of the knockout phenotype by probucol.

Fig. 4.

SR-B1 expression in ovaries. (A) Ovaries from wild-type or CCTβ2−/− mice treated or untreated with 2% probucol were fixed, embedded in paraffin wax, and sectioned. Slides were stained to reveal the presence of SR-B1 protein (brown) as described under “Materials and Methods.” CL indicates the corpus luteum, and the arrows (→) point to interstitial cells, both of which are the main sites of SR-B1 expression. Scale bar = 50 μm. The images were representative of three mice examined in each group. (B) Transcript levels for the SR-B1 and LDL receptor expression in ovaries from wild-type or CCTβ2−/− mice, untreated or treated with 2% probucol were measured using the primers and probes listed in Table 1. The results are the mean values ± s.d. (n = 3).

3.6. Probucol does not alter PtdCho synthesis

The exact mechanism of probucol-induced HDL lowering is not known, and so we investigated whether probucol increased endogenous PtdCho synthesis, thereby overcoming the deficit in the knockout animals. Probucol was added to Y-1 adrenocortical cultured cells in concentrations ranging from 5 to 80 μM and synthesis of radiolabeled PtdCho from [3H]choline was measured over a 6-hr incubation period. Y-1 cells were chosen because they are known to be HDL-responsive since they express the SR-B1 receptor [13] and express CCTα only (not shown), similar to the CCTβ2−/− knockouts. There was no difference in the total radiolabel incorporated into cells and no difference in the incorporation of radiolabel into PtdCho among the probucol-treated cells compared to untreated controls (data not shown). The in vitro enzymatic activity of CCTα was evaluated using purified recombinant CCTα and an established enzymatic assay. Again, there was no alteration imposed by probucol on the initial rate of CDP-choline production (data not shown). Additionally, we checked expression of the phosphatidylethanolamine methyltransferase in wild-type and knockout ovaries after treatment with probucol and found that there was no significant difference in the level of transcripts (data not shown). These control experiments ruled out a direct stimulation of the endogenous PtdCho biosynthesis as an explanation for the enhanced fertility observed in the CCTβ2-null females.

Discussion

The correction of the fertility defect in a significant number of CCTβ2−/− females by probucol (Fig. 2) correlates with decreased serum PtdCho levels (Fig. 3), and increased PtdCho in the ovary (Table 3). Either stimulation of serum lipoprotein uptake and/or increased retention of PtdCho by probucol was able to bypass the genetic defect in de novo PtdCho biosynthesis in the knockout oocytes. The PtdCho content of the knockout gonads was lower than wild-type, and increased upon probucol treatment to a level equivalent to wild-type (Table 3), in support of the hypothesis. HDL is composed of approximately equal amounts of cholesterol and PtdCho, and HDL supplies and extracts both lipids to and from tissues. Probucol lowers plasma HDL, thereby lowering the serum cholesterol levels and oftentimes raising tissue cholesterol levels [10], as it did in the knockout ovary. The ratio of PtdCho to cholesterol was maintained at approximately 1.4 in the CCTβ2-null ovaries, and the PtdCho content increased in proportion to the size of the organ, suggesting a balance between PtdCho, a major membrane component, and the disposition of cholesterol. In the wild-type ovary, the PtdCho content was also maintained as a function of the weight of the organ, but the size diminished due to a major reduction in cholesterol content. These data suggest that a threshold of cellular PtdCho is maintained either by in situ synthesis or uptake from extracellular sources.

SR-B1 is a major receptor for the uptake of HDL, the major serum lipoprotein in mice, and SR-B1 knockout females are sterile due to oocyte defects [15], similar to the CCTβ2 knockouts. Cholesterol derived from HDL uptake is required to support steroid production in the ovary, and a deficiency in steroid hormone production correlates with the reproductive defect in SR-B1 knockouts [20]. Steroid hormone production is not deficient in the CCTβ2-null mice, however, indicating that the cholesterol supplied by HDL is sufficient for steroidogenesis. Probucol also completely reverses the female infertility in the SR-B1-deficient mice [20], demonstrating that the stimulation of HDL-mediated delivery of cholesterol by probucol is independent of SR-B1. Circulating hepatic lipase (HL) facilitates the selective uptake and mobilization of cholesterol by hydrolyzing the phospholipids and triglycerides within the HDL particle. HL−/− knockout mice have reduced progesterone production, decreased ovulation and reduced litter sizes [28]. Thus, the fertility defect in CCTβ2−/− females is reminiscent of the HL and the SR-B1 knockouts and the probucol reversal of the ovary dysfunction reflects the findings in SR-B1-null mice. In our case, probucol is proposed to correct the PtdCho supply to a tissue deficient in the biosynthesis of this membrane component rather than cholesterol.

While CCTβ2 is expressed very highly in wild-type maturing oocytes, its expression is not detected in the surrounding follicular cells [4]. Oocyte and follicle development are interdependent [25], thus a deficit in oocyte function in the CCTβ2−/− defect mice was reflected in problematic follicle formation as well. The morphological changes in degenerating CCTβ2−/− ovaries indicate reduced intercellular communication between the ova and the surrounding granulosa cells. This intimate relationship is essential for folliculogenesis and depends on transmission of signals between the two cell types. Granulosa cells provide nutrients as well as molecular signals that regulate oocyte development, including growth factors and steroids. In particular, estradiol synthesis occurs in the granulosa cells and participates in the control of follicular growth and maturation [27]. However, estradiol production was not defective in CCTβ2−/− females. The oocyte itself also plays a role in follicle development, and the release of oocyte factors relay signals to the surrounding somatic cells [25]. The lack of CCTβ2 isoform expression leads to a pronounced disruption in the Golgi complex of the oocyte and decreased organization of secretory granules in the oocyte and granulosa cells. This finding suggests that a disruption in the secretion of hormones may contribute to the phenotype, which in turn would depress follicle maturation. These data are consistent with the CCTβ2−/− defect occurring primarily in membrane biogenesis within the oocyte. Our finding also suggests an alternate explanation for observations in tissue-specific CCTα−/− knockout mice. Despite the lack of expression of the major CCT isoform, CCTα−/− macrophages [5], liver [6] and lung [7] all develop normally. These results indicate that the relatively low expression CCTβ expression is sufficient for proliferation and differentiation, perhaps in conjunction with PtdCho supplementation from the circulating lipoproteins.

Table 2.

Comparison of serum progesterone and estradiol levels in wild-type and CCTβ2−/− mice.

| Mouse Genotype | Progesterone (ng/ml) | Estradiol (pg/ml) |

|---|---|---|

| Wild-Type | ||

| Virgin | 6.48 ± 2.15 (n=10) | 24.96 ± 4.9 (n=10) |

| Pregnant | 31.55 ± 11.92 (n=13)* | 24.81 ± 7.04 (n=13) |

| CCTβ2−/− | ||

| Virgin | 5.61 ± 2.83 (n=4) | 27.49 ± 5.13 (n=4) |

| Pregnant | 26.8 ± 2.53 (n=7)* | 26.79 ± 2.53 (n=3) |

| CCTβ2−/− + Probucol | ||

| Virgin | 8.68 ± 5.23 (n=4) | 27.41 ± 5.6 (n=7) |

| Pregnant | 9.88 ± 4.65 (n=11) | N.D. |

Hormone levels were measured using a radioimmunoassay as described under Materials and Methods. N.D. means not determined. Data analysis using the students t-test showed a significant difference (*p<0.05) between progesterone levels in virgin and pregnant untreated mice of each genotype. All other values were not significantly different.

Acknowledgments

Supported by National Institutes of Health Grants GM 45737 (S.J.), Cancer Center (CORE) Support Grant CA 21765, and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities. We thank Chuck Rock for critical evaluation of the data, Pam Jackson for expert technical contributions, and Linda Mann, Scientific Imaging Shared Resource, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jackowski S, Fagone P. CTP: Phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase: paving the way from gene to membrane. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:853–856. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R400031200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karim MA, Jackson P, Jackowski S. Gene structure, expression and identification of a new CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase β isoform. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1633:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(03)00067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang L, Magdaleno S, Tabas I, Jackowski S. Early embryonic lethality in mice with targeted deletion of the CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase α gene (Pcyt1a) Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:3357–3363. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.8.3357-3363.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jackowski S, Rehg JE, Zhang YM, Wang J, Miller K, Jackson P, Karim MA. Disruption of CCTβ2 expression leads to gonadal dysfunction. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:4720–4733. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.11.4720-4733.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang D, Tang W, Yao PM, Yang C, Xie B, Jackowski S, Tabas I. Macrophages deficient in CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase-α are viable under normal culture conditions but are highly susceptible to free cholesterol-induced death. Molecular genetic evidence that the induction of phosphatidylcholine biosynthesis in free cholesterol-loaded macrophages is an adaptive response. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:35368–35376. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007099200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacobs RL, Devlin C, Tabas I, Vance DE. Targeted deletion of hepatic CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase a in mice decreases plasma high density and very low density lipoproteins. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:47402–47410. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404027200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tian Y, Zhou R, Rehg JE, Jackowski S. Role of phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase α in lung development. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:975–982. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01512-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta T, Schüpbach T. Cct1, a phosphatidylcholine biosynthesis enzyme, is required for Drosophila oogenesis and ovarian morphogenesis. Development. 2003;130:6075–6087. doi: 10.1242/dev.00817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weber U, Eroglu C, Mlodzik M. Phospholipid membrane composition affects EGF receptor and notch signaling through effects on endocytosis during Drosophila development. Dev Cell. 2003;5:559–570. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00273-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rigotti A, Miettinen HE, Krieger M. The role of the high-density lipoprotein receptor SR-BI in the lipid metabolism of endocrine and other tissues. Endocr Rev. 2003;24:357–387. doi: 10.1210/er.2001-0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schuler LA, Scavo L, Kirsch TM, Flickinger GL, Strauss JF., III Regulation of de novo biosynthesis of cholesterol and progestins, and formation of cholesteryl ester in rat corpus luteum by exogenous sterol. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:8662–8668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dyer CA, Curtiss LK. Apoprotein E-rich high density lipoproteins inhibit ovarian androgen synthesis. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:10965–10973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Temel RE, Trigatti B, DeMattos RB, Azhar S, Krieger M, Williams DL. Scavenger receptor class B, type I (SR-BI) is the major route for the delivery of high density lipoprotein cholesterol to the steroidogenic pathway in cultured mouse adrenocortical cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:13600–13605. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andersen JM, Dietschy JM. Relative importance of high and low density lipoproteins in the regulation of cholesterol synthesis in the adrenal gland, ovary, and testis of the rat. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:9024–9032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trigatti B, Rayburn H, Vinals M, Braun A, Miettinen H, Penman M, Hertz M, Schrenzel M, Amigo L, Rigotti A, Krieger M. Influence of the high density lipoprotein receptor SR-BI on reproductive and cardiovascular pathophysiology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:9322–9327. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beck BJ, Aldrich CC, Fecik RA, Reynolds KA, Sherman DH. Iterative chain elongation by a pikromycin monomodular polyketide synthase. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:4682–4683. doi: 10.1021/ja029974c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsujita M, Wu CA, be-Dohmae S, Usui S, Okazaki M, Yokoyama S. On the hepatic mechanism of HDL assembly by the ABCA1/apoA-I pathway. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:154–162. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400402-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu CA, Tsujita M, Hayashi M, Yokoyama S. Probucol inactivates ABCA1 in the plasma membrane with respect to its mediation of apolipoprotein binding and high density lipoprotein assembly and to its proteolytic degradation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:30168–30174. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403765200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tomimoto S, Tsujita M, Okazaki M, Usui S, Tada T, Fukutomi T, Ito S, Itoh M, Yokoyama S. Effect of probucol in lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase-deficient mice: inhibition of 2 independent cellular cholesterol-releasing pathways in vivo. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:394–400. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.21.3.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miettinen HE, Rayburn H, Krieger M. Abnormal lipoprotein metabolism and reversible female infertility in HDL receptor (SR-BI)-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1717–1722. doi: 10.1172/JCI13288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garber DW, Kulkarni KR, Anantharamaiah GM. A sensitive and convenient method for lipoprotein profile analysis of individual mouse plasma samples. J Lipid Res. 2000;41:1020–1026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bligh EG, Dyer WJ. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1959;37:911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luche MM, Rock CO, Jackowski S. Expression of rat CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase in insect cells using a baculovirus vector. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1993;301:114–118. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lykidis A, Jackson P, Jackowski S. Lipid activation of CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase α: Characterization and identification of a second activation domain. Biochemistry. 2001;40:494–503. doi: 10.1021/bi002140r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matzuk MM, Burns KH, Viveiros MM, Eppig JJ. Intercellular communication in the mammalian ovary: oocytes carry the conversation. Science. 2002;296:2178–2180. doi: 10.1126/science.1071965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirano K, Ikegami C, Tsujii K, Zhang Z, Matsuura F, Nakagawa-Toyama Y, Koseki M, Masuda D, Maruyama T, Shimomura I, Ueda Y, Yamashita S. Probucol enhances the expression of human hepatic scavenger receptor class B type I, possibly through a species-specific mechanism. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:2422–2427. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000185834.98941.3d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eppig JJ. Intercommunication between mammalian oocytes and companion somatic cells. Bioessays. 1991;13:569–574. doi: 10.1002/bies.950131105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wade RL, Van Andel RA, Rice SG, Banka CL, Dyer CA. Hepatic lipase deficiency attenuates mouse ovarian progesterone production leading to decreased ovulation and reduced litter size. Biol Reprod. 2002;66:1076–1082. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod66.4.1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]