Abstract

The disease dengue (DEN) is caused by four serologically related viruses termed DEN1, DEN2, DEN3 and DEN4. The structure of the ectodomain of the envelope protein has been determined previously for DEN2 and DEN3 viruses. Using NMR spectroscopic methods, we have solved the solution structure of domain III (ED3), the receptor-binding domain, of the envelope protein of DEN4 virus, human strain 703–4. The structure shows that the nine amino acid changes in ED3 that separate the sylvatic and human DEN4 strains are surface exposed. Important structural differences between DEN4-rED3 and ED3 domains of DEN2, DEN3 and other flaviviruses are discussed.

Introduction

The flaviviruses (family Flaviviridae, genus Flavivirus) are typically transmitted by either mosquitoes or ticks and include major human pathogens such as dengue (DEN), West Nile (WN), yellow fever (YF), Japanese encephalitis (JE) and tick-borne encephalitis (TBE) viruses. The disease DEN is the most important arthropod-borne viral disease causing 50–100 million cases of DEN fever each year and is transmitted between humans by the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Since there are no vaccines or antiviral agents to prevent DEN, there is great interest at developing strategies to control this disease. Dengue is caused by four serologically and genetically distinct viruses termed DEN1, DEN2, DEN3 and DEN4. Phylogenetic studies show that DEN4 is the oldest of the four DEN viruses, and human dengue viruses have evolved from sylvatic progenitors that are maintained in nature in a mosquito-monkey transmission cycle (Wang et al., 2000). Surprisingly, only nine amino acid mutations in ED3 separate the two most divergent DEN4 strains: sylvatic P65–215 and human 703–4. Of these nine changes, six have been implicated in the emergence of the human DEN4 virus (Wang et al., 2000; Twiddy et al., 2002).

Located on the surface of the virion, the flavivirus envelope (E) protein represents the primary immunogen and plays a central role in receptor binding and membrane fusion (Heinz and Allison, 2000, 2001, 2003). Three distinct domains (domains I, II and III or ED1, ED2 and ED3) have been identified in the N-terminal 400 amino acids of the E protein both by immunological methods (Mandl et al., 1989; Crill and Roehrig, 2001; Roehrig, 2003) and by x-ray crystallographic studies of the dimeric extra-membrane portion of the E-proteins from Central European TBEV (Rey et al., 1995), DEN2 (Modis et al., 2003), DEN3 (Modis et al., 2005) and WN (Modis et al., 2006; Nybakken et al., 2006) viruses. NMR-derived solution structures of the JE (Wu et al., 2003), WN (Volk et al., 2004), Omsk hemorrhagic fever (OHF) virus (Volk et al., 2006) and Langat (LGT) virus (Mukherjee et al., 2006) ED3 illustrate an overall similar structural fold for these flaviviruses. Cryoelectron microscopic reconstructions of several mosquito-borne flaviviruses indicate that the E protein is arranged as dimers on the virion surface, such that ED3 projects slightly above the viral surface (Kuhn et al., 2002; Mukhopadhyay et al., 2003). Interactions between five ED3 subunits at the virion 5-fold axes of symmetry form pores on the virion surface to which antibodies or receptors may bind. After cell binding and endosomal encapsulation, a low pH-induced structural change exposes the viral fusion peptide in ED2, after which the virus and endosome fuse and viral RNA is released into the cell cytoplasm (Modis et al., 2004).

The objective of this study was to determine the structural characteristics of the DEN4-rED3 that may be related to antigenic differences between DEN virus types and potential host cell interactions (i.e., sylvatic DEN vs. human DEN). ED3 has been reported to be the receptor-binding domain of the virus (Hung et al., 2004; Chu et al., 2005) leading to the hypothesis that variations in the structure and surface chemistry of ED3 between different flaviviruses may affect host cell receptor interactions and may play a role in variations in viral pathogenesis.

Results

Quality of the NMR Structures

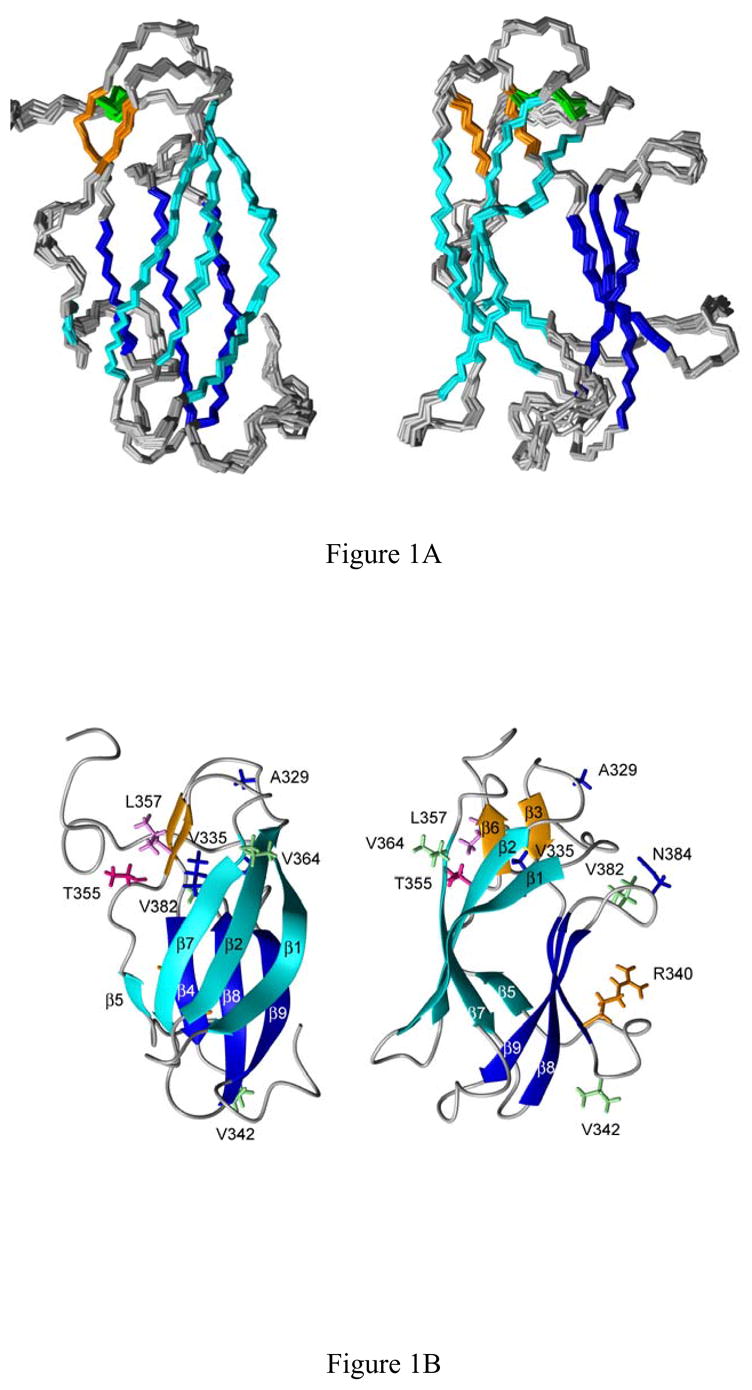

The 15 final structures in the ensemble (Figure 1) had low molecular and restraints energy penalties. The structure presented here is well-defined, as shown by the r.m.s.d. values and restraint violations listed in Table 1. The final structures had 27 ± 4 distance restraint violations over 0.3 Å, 3 ± 1 violations over 0.5 Å and 3 ± 1 dihedral angle violations over 20º (Table 1). Thus, 99.8% of the NOE restraints fit the structures determined. The violations occur because the NOE interactions and cutoff distances were set in an automated fashion into one of five distance bins based on crosspeak volumes, disregarding confounding effects such as amide proton exchange rates, equivalent geminal groups and differing spin-spin relaxation rates. One could move borderline peak volumes into less restrictive distance bins to remove these violations. Likewise, the dihedral angle restraints based either on chemical shift or HNHA data overlap in angle space to a varying degree. The r.m.s.d. on the distance restraint error was 0.018 ± 0.001 A, and the r.m.s.d. on dihedral angle error was 0.27 ± 0.05º. The structural ensemble has a global backbone atom r.m.s.d. of 0.75 ± 0.14 Å, and a global heavy atom r.m.s.d. of 1.08 ± 0.17 Å. Residues 296–393 also have low backbone atom r.m.s.d values, 1.19 and 1.42 Å, respectively, compared to the DEN2 (Modis et al., 2003) and DEN3 (Modis et al., 2005) virus E protein X-ray structures.

Fig. 1.

A, Two orthogonal views of the NMR-derived DEN4-rED3 backbone atom structures. Beta sheets 1–3 are colored cyan, orange and blue, respectively, and the disulfide bond between C14 and C45 is shown in green. B, Two orthogonal side-views of a ribbon diagram of the Den4-rED3 NMR structure. The side chains of residues which differ between the two most divergent human (703–4) and sylvatic (P75-215) strains of DEN4-rED3 are shown as sticks.

Table 1.

Summary of NMR structure constraints and statistics

| 2071 | |

| Total Restraints | |

| NOE restraints | 1419 |

| Intra-residue | 469 |

| Sequential | 385 |

| Medium range | 95 |

| Long range | 470 |

| Talos phi/psi dihedral restraints | 160 |

| HNHA phi dihedral restraints | 51 |

| H-bond restraints | 46 |

| Omega dihedral restraints | 111 |

| Chirality restraints | 284 |

| Structural Statistics | |

| NOE violations > 0.5 Å | 3 ± 1 |

| NOE violations > 0.3 Å | 27 ± 4 |

| Dihedral angle violation > 20º | 3 ± 1 |

| Dihedral angle violation > 10º | 14 ± 3 |

| r.m.s.d from ideal geometry | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.013 |

| Bond angles (º) | 2.3 |

| Restraint error r.m.s.d. | |

| Distance restraints (Å) | 0.036 ± 0.001 |

| Dihedral restraints (º) | 1.15 ± 0.06 |

| Atomic r.m.s.d. | |

| Backbone atoms | 0.75 ± 0.14 |

| All heavy atoms | 1.08 ± 0.17 |

| Ramachandran statistics | |

| Most favored regions (%) | 73.6 |

| Additionally allowed regions (%) | 23.4 |

| Generously allowed regions (%) | 2.0 |

| Disallowed regions (%) | 1.0 |

The program PROCHECK (Laskowski et al., 1996) was used to analyze the quality of the final ensemble. Analysis of the non-glycine, non-proline residues indicated that 97.0% of the residues are in the two most favored regions of a Ramachandran plot. Specifically, 73.6% of the residues are in the most favored regions, 23.4% of the residues are in the additionally allowed region, 2.0% of the residues are in the generously allowed regions and 1.0% of the residues are in the disallowed regions.

Structural Details of the NMR ensemble

The protein structure consists of three β-sheets arranged in a β-barrel configuration (Fig. 1B). The first beta sheet, whose upper, outer face is exposed in the viral particle, consists of βstrands β1, β2, β5 and β7 at residue positions F306-E314 (β1, with a bulge at 309–312), T320-Y326 (β2), R350-I351 (β5) and V365-E370 (β7). In an E protein dimer nearly half of this beta sheet interacts with ED2 of the opposing protein monomer. The small second beta sheet consists of beta strands β3 and β6 at residue positions C333-K334 (β3) and L357-A358 (β6). The outer face of this beta sheet faces ED1 of the same E protein (Modis et al, 2003; Modis et al. 2005). The third beta sheet consists of beta strands β4, β8, and β9 positioned at residues F337-R340, D375-I380 (β8), and L387-F392 (β9). This beta sheet is the farthest from the virion particle surface. All three beta sheets are also present in the DEN2 and DEN3 ED3 protein structures, however, β5 differs among the viruses. In both the DEN3 (R348-L349) and DEN4 (R350-I351) viruses, β5 is only two amino acids long, while in the DEN2 virus, the twisted β5 strand (V347-L351) contains of an addition three amino acids on the N-terminal side. This region of the flavivirus ED3 shows considerable variation.

Binding of DEN complex monoclonal antibodies to ED3

Although epitopes in ED3 are primarily virus type- or subtype-specific, many studies have identified monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) that are DEN complex specific (i.e., recognize the E protein of DEN1, DEN2, DEN3 and DEN4 viruses only). We examined the binding of two commercially available DEN complex-reactive MAbs, GTX29202 and MDVP-55A (see Materials and Methods), that both recognized ED3 by Western blot (Figure 2). Since the structural data suggested that there are distinct differences among the structure and surface chemistry of ED3 for DEN2, DEN3 and DEN4 viruses, we examined the binding of these two DEN complex MAbs to rED3s representing all four DEN virus types. The two MAbs bound tightly to DEN1 rED3 (Kd = 0.06–0.08nM) and DEN2 rED3 (Kd = 0.2nM), less tightly to DEN3 rED3 (6–8nM) and very poorly to DEN4 rED3 (≥3μM) (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Western blot of recombinant DEN1, DEN3, DEN4 and West Nile virus ED3s using Mab MDVP-55A at 0.67μg/ml.

Table 2.

Dissociation constants (Kd) of DEN Complex MAbs with DEN1, DEN2, DEN3 and DEN4 rED3.

| MAb | DEN1 | DEN2 | DEN3 | DEN4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GTX29202 | 0.08±0.00 nM | 0.21+0.01 nM | 8.0+1.1 nM | >3.0 μM |

| MDVP-55A | 0.06+0.00 nM | 0.23+0.02 nM | 6.1+1.1 nM | >3.0 μM |

Discussion

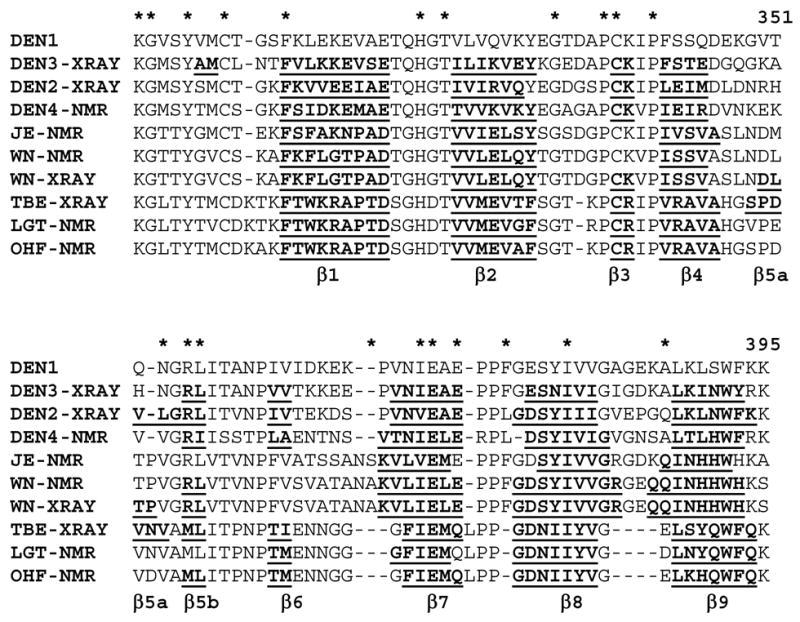

The solution structure of the DEN4-rED3 reported here represents the first NMR structure of a DEN virus-encoded protein subunit. The overall structure is similar to those of the DEN2 and DEN3 ED3 structures obtained by X-ray crystallography (Modis et al., 2003; Modis et al., 2005) as well as those of related flaviviruses. Although the flavivirus ED3s share only 40–60% amino acid homology as a group, nine beta strands are regularly found in these proteins (Figure 3). Beta strands one through four are nearly identical in all of the flavivirus structures, although β3 was not observed in the NMR structures of the JE and WN viruses, both members of the JE serocomplex. Beta strands β8 and β9 are nearly consistent across all of the structures, although they are both slightly longer in both the WN NMR and x-ray determined structures.

Fig. 3.

Sequence alignment of flavivirus ED3 sequences. Beta sheet secondary structure is indicated by underlined bold characters.

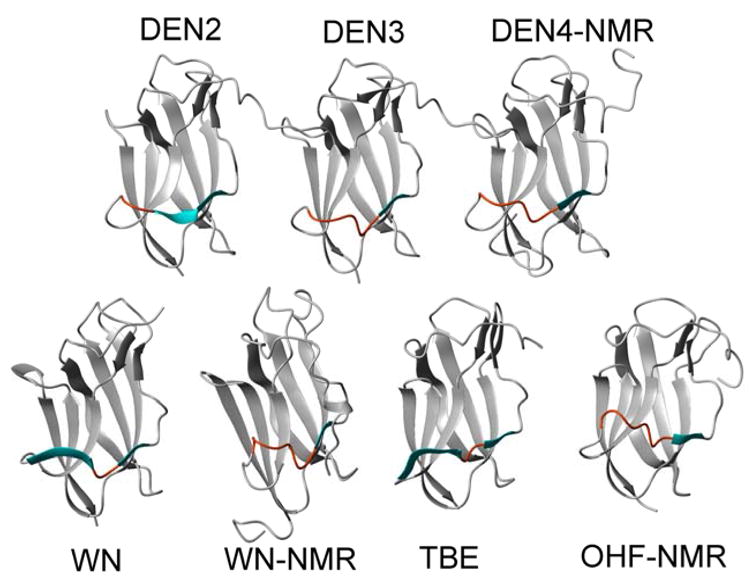

In contrast, a large variability is observed in beta strands β5, β6 and β7 (Figures 3 & 4). With the exception of the JE and LGT NMR structures, all of the ED3 structures contain a two-residue beta strand (β5b). In DEN2 ED3, this beta strand is extended on the N-terminal side by an additional three amino acids (β5a), connected with a significant twist. This extension of the beta sheet is not observed in the DEN3 crystal structure or in the majority (of each NMR ensemble) of the flavivirus NMR structures deposited. However, it should be noted that this, or a similar extension, is observed in one (WN, OHF) to five (LGT) of the NMR structures of each ensemble. In the WN and TBE X-ray structures, beta strand β5a is longer and is separated from strand β5b by one or two residues. Strand β6 in ED3 is likewise variable among the flaviviruses. This strand is observed in all E protein structures for DEN viruses and in the tick-borne TBE, LGT and OHF structures determined by NMR or X-ray crystallography. However, it is not observed in the JE serocomplex virus ED3 structures (JE and WN) determined by X-ray (Nybakken et al., 2006) or NMR (Volk et al., 2004; Wu et al., 2003) methods. Finally, although strand β7 is nearly consistent among the mosquito-borne viruses, it is slightly shorter in all of the tick-borne virus structures (TBE, OHF and LGT).

Fig. 4.

Ribbon diagrams of several flavivirus ED3 proteins illustrating their backbone structural differences near beta strand five. Beta strands β5a (always present) and β5b (sometimes present) are shown in cyan while the same region is colored orange when beta sheets are not present.

Inspection of the structures indicates that the variable beta strands 5–7 all reside on one side of the ED3 (Figure 1). In the dimeric E-protein structure, this side interacts with domain ED1 of the same monomer unit. As a whole, the flavivirus structural data suggest that this region of the protein is more variable and dynamic than the rest of the ED3. Indeed, strand β6 is missing in both the NMR and X-ray structures of WN ED3 as well as in the JE structure, as is the neighboring strand β3 (Nybakken et al., 2005; Volk et al., 2004; Wu et al., 2003). The observation that the beta strands are present in a small number of models in each NMR ensemble is consistent with a more dynamic protein region, although relaxation measurements have only been reported for the Langat virus ED3, which also support this idea (Mukherjee et al. 2006). The extra length of strand β5 (β5a) in the DEN2, WN and TBE X-ray structures (Figure 4), compared to DEN3 is also consistent with this interpretation. While this region is expected to be more dynamic in an NMR structure in which the isolated ED3 protein is used, the DEN3 structure is based on the intact E-protein in a dimeric context. Thus, the stability of this region (loop or β5a) appears to be highly dependent on the crystal or solution conditions under which the data were collected.

Although the four DEN viruses share a common name, they are in fact serologically and genetically distinct viruses (Calisher et al., 1989; Twiddy et al., 2003). Despite the similarity of the flavivirus ED3 secondary structures and overall fold, each virus displays a unique surface to which cell receptors or antibodies might bind (Figure 5). Very importantly, the electrostatic surfaces of the DEN2, DEN3 and DEN4 ED3 proteins, as viewed from the center of the virion 5-fold pore (Figure 5A–C) clearly show dramatic surface differences among these viruses. DEN2 has significantly more negative charges near the bottom of the ED3 protein compared to DEN3 and DEN4, while DEN3 displays significantly more negative charge near the upper surface of the ED3 protein. In contrast, the distinguishing feature of the DEN4 is the greater amount of uncharged surface area relative to the other two viruses. When viewed from above the virion surface (Figure 5D–F) the exposed surfaces again show distinct patterns. The top of the DEN2 ED3 surface contains a mix of positive and negative charges, while the DEN3 viral surface has a dominant negative area. The DEN4 virus ED3 is notable for its mostly neutral upper binding surface.

Fig. 5.

Electrostatic exposed surface of ED3. Blue indicates positive charge while red indicates negative charge. A–C. Electrostatic surface of the DEN2, DEN3and DEN4 viruses as viewed from within the 5-fold virion pore. The virion surface is located at the top of these images. D–F. Electrostatic view of the DEN2, DEN3 and DEN4 ED3 proteins as viewed from above the virion surface.

Studies with several flavivirus have shown that ED3 encodes the major virus-specific neutralization site, which consists of overlapping epitopes. Although there have been no studies of neutralizing ED3 epitopes for DEN4 virus, examination of DEN2 ED3 protein with neutralizing virus type-specific MAbs indicates that these antibodies interact primarily with residues in the surface-exposed loops of ED3 protein and that the specificity of their epitopes is associated with variations in charge or hydrophobicity of the surface of ED3 protein (Lin et al., 1994; Hiramatsu et al., 1996; Lok et al., 2001; Gromowski et al., in preparation). Given the differences in electrostatic charge on the surfaces of ED3 of DEN2, DEN3 and DEN4 viruses, it was predicted that these are important determinants of differences in antigenicity and other biological properties of these viruses. The differences in DEN ED3 antigenicity were confirmed here by examining the binding of two DEN complex-reactive MAbs to DEN1, DEN2, DEN3 and DEN4 rED3 proteins. Both MAbs had great differences in Kd values when the four DEN rED3s were compared (Table 2) demonstrating that, although there is some degree of antigenic conservation between ED3 of DEN virus types, even “conserved” epitopes in DEN ED3 differ significantly in their recognition by complex reactive MAbs. Furthermore, Western blotting of DEN1, DEN3 and DEN4 rED3s with MAb MDVP-55A confirmed that this MAb recognized all three ED3s, including a weak reaction with DEN4 rED3 that is consistent with the physical binding data (Table 2).

It has also been hypothesized that DEN viruses originally existed in a sylvatic cycle involving mosquitoes and monkeys, in the absence of human disease, but evolved into a human virus causing disease with a cycle involving humans and Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. Comparison of the E proteins of human isolate 703–4 with sylvatic isolate P75-215 reveals that there are 9 amino acid differences in ED3, of which 5 (K340R, M342V, I335T, I364V and A382V) have been implicated from phylogenetic studies (Wang et al., 2000) in the emergence of DEN4 from a sylvatic virus to a human virus. Examination of DEN4 ED3 protein structure presented here reveals that, although all five residues are conservative changes, they are surface exposed suggesting that the emergence of human DEN may have been in part due to changes in cell receptor-binding properties of ED3.

Materials and Methods

Protein Expression and Purification

Uniformly 15N-labeled, 15N,13C-labeled and unlabeled human Den4-rED3 proteins (strain 704–3, GenBank AAF61130, UNP Q9IZI6) encompassing residues M289-K400, were expressed using the pET-15 vector (Novagen), but lacking the N-terminal His-tag sequence encoded in that plasmid. To avoid aggregation, the crude cell debris was first denatured using 8 M urea. Urea was then removed by dialysis (3 x 1/2000 dilution). The expressed proteins were purified over a Sephadex Q-column and were subsequently filtered through an Amicon centrifugal concentrator with a 30 kDa molecular weight cut-off to remove proteins with higher molecular weights. Centricon concentrators with a 3 kDa cut-off were used for the final concentration step and to remove low-molecular weight impurities as well as to exchange the material into the final NMR buffer.

NMR Spectroscopy and the Generation of NMR Restraints—

The NMR samples contained 0.6 mM protein in 50 mM deuterated Tris (pH 7.5) and 50 mM NaCl in 90% H2O and 10% D2O or 100% D2O. All experiments were acquired on Varian UnityPlus 600 or Varian Inova 750 or 800 MHz spectrometers equipped with Direct Drive architecture at 25 °C. Sequence-specific chemical shifts (Volk et al., 2006a) for the backbone resonances were obtained from three-dimensional HNHA (Vuister and Bax, 1996), HNCA (Kay et al., 1994), HNCOCA (Yamazaki et al., 1994), HNCACB (Sattler et al., 1999), CBCACONH (Grzesiek and Bax, 1992), HNCO (Ikura et al., 1990) and HCACOCANH (Lohr and Ruterjans, 1995) experiments. The backbone assignments were verified by sequential NOE connectivities observed in an 15N-edited HSQC-NOESY experiment (Marion et al., 1990) with a 150 ms. mixing time acquired at 750 MHz. Side chain assignments were derived from HCCH-TOCSY (Vuister and Bax, 1992), 15N-edited TOCSY (Kay et al., 1992), H(CCO)NH-TOCSY (Clore, G. M. and Gronenborn , 1994) and CC(CO)NH-TOCSY (Clore, G. M. and Gronenborn, 1994) experiments. Aromatic proton chemical shifts were assigned from resonances in a CT-1H,13C-HSQC (John et al., 1993) spectrum, NOE spectra, HCBCGCDHD (Yamazaki et al., 1993), HCBCGCDCDHE (Yamazaki et al., 1993) and an HCCH-TOCSY (Bax et al., 1990) experiment centered on the aromatic carbon region. Stereo-specific assignments for some of the side-chain protons were obtained after initial rounds of structure calculations using unambiguous restraints. All spectra were processed with VNMR v6.1b (Varian, Inc.) or Felix2000 (Accelrys, Inc.) software.

SANE (Duggan et al., 2001) was used to facilitate the assignment of the 2D and 15N-edited NOE cross peaks and for the generation of restraints. Chemical shifts, distance cutoffs and contribution cutoffs were used within the program. The NMR restraints were separated into five bins, based on the NOESY cross-peak volumes from which they were derived, with upper distance limits of 2.5, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0 and 6.0 Å. The 1419 NOE-based restraints (see Table 1) consist of 469 intra-residue, 385 sequential, 95 medium-range and 470 long-range distance restraints.

TALOS (Cornilescu et al., 1999) was used to derive 160 phi/psi dihedral angle restraints based on the chemical shifts of the amino acids. An additional 51 phi angle restraints were derived from an HNHA experiment. Fifty-one hydrogen bond restraints were added based on the structures obtained in the initial structure calculations and strong peaks.

Molecular Dynamics Calculations

One hundred random structures were generated by annealing the protein at 700 K, obtaining the coordinates every 5 ps and minimizing the structures obtained. The structures were then subjected to r-MD using dihedral angle restraints (Table 1) followed by the application of all restraints at 300 K. Finally, the structures were energy minimized for 5,000 steps. Fifteen structures with low restraint penalties were then chosen for the structural ensemble. The SANDER module within AMBER6.0 (Case et al., 1999) was used for all NMR structure calculations and MIDAS (Ferrin et al., 1988) and MOLMOL (Koradi et al., 1996) were used to visualize the structures. Coordinates for the ensemble of NMR structures of Den4-rED3 have been deposited with the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID 2H0P) and the chemical shifts (Volk et al., 2006a) have been deposited with the BioMagResBank (accession code 7087).

Affinity Measurements by Indirect ELISA

The DEN complex Mabs GTX29202 (GeneTex, Inc.) and MDVP-55A (Immunology Consultants Laboratory, Inc.), which react with ED3 of DEN viruses 1–4, were tested for their affinity to recombinant, MBP-tagged, ED3s (rED3) for DEN1 strain OBS7690, DEN2 strain 16681, DEN3 strain H87, and DEN4 strain 703–4. The wells of 96-well microtiter plates (Corning Inc., Corning, N.Y.) were coated with 200 ng of rED3 diluted in borate saline pH 9.0 at 37ºC for 2 hours. This amount of rED3 was determined to saturate the wells by using anti-MBP antisera (NEB) (data not shown). Wells were washed twice with purified water and blocked for 30 minutes at room temperature (25ºC) with blocking buffer [phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), 0.1% (v/v) Tween-20, 0.25% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA)] and subsequently washed twice with purified water. Both MAbs were diluted to either 5 nM, 40 nM, 400 nM, or 3800 nM concentrations for affinity determination with DEN-1, -2, -3, and -4 rED3s, respectively. These MAb dilutions were added to duplicate wells followed by 11 two-fold serial dilutions in blocking buffer. The MAb concentrations used were determined to cover the full range of binding, from undetectable binding to saturation, for each DEN rED3 except DEN-4 in which case the full range of binding could not be achieved. MAbs were allowed to bind overnight at room temperature (25ºC) for 15–18 hours. Subsequently, the microtiter plates were washed twice with purified water and twice with PBS-T (PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20) followed by addition of a 1/1000 dilution of HRP conjugated goat anti-mouse-immunoglobulins (Sigma) and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. Following this incubation microtiter plates were washed twice with purified water and twice with PBS-T. Antibody binding was visualized by addition of 3, 3’, 5, 5’-tetramethylbenzidene substrate (Sigma). After 30 minutes of incubation at room temperature the absorbance was read at 655nm on a model 3550-UV plate reader (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Binding curves and Kd values were determined using SigmaPlot (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants U90CCU618754 from the Centers for Disease Control, a grant from the Pediatric Dengue Vaccine Initiative, U01 AI054827 from NIAID, H1296 from the Welch Foundation, P42296LS0000 from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, DAAD17–01-D-0001 from the Defense Threat Reduction Agency, 004952–0038–2003 from the State of Texas Advanced Technology Program, fellowships from the James W. McLaughlin Fellowship Fund to D.W.C.B., and T32 AI 07526 to G.D.G.

Footnotes

The atomic coordinates of the NMR solution structure (2H0P) have been deposited with the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/). NMR Chemical shifts (7087) have been deposited at the BioMagResBank, University of Wisconsin-Madison (http://www.bmrb.wisc.edu/).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bax A, Clore GM, Gronenborn AM. H-1-H-1 correlation via isotropic mixing of C-13 magnetization, a new 3-dimensional approach for assigning H-1 and C-13 spectra of C-13 enriched proteins. J Mag Reson. 1990;88:425–431. [Google Scholar]

- Calisher CH, Karabatsos N, Dalrymple JM, Shope RE, Porterfield JS, Westaway EG, Brandt WE. Antigenic relationships between flaviviruses as determined by cross-neutralization tests with polyclonal antisera. J Gen Virol. 1989;70:37–43. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-70-1-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case DA, Pearlman DA, Caldwell JW, Cheatham TE, Rose WS, III, Simmerling CL, Darden KM, Merz RV, Stanton AL, Cheng JJ, Vincent M, Crowley DM, Ferguson RJ, Radmer GL, Seibel UC, Singh PK, Weiner SJ, Kollman PA. AMBER6.0. University of California; San Francisco, CA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Chu JJ, Rajamanonmani R, Bhuvanakantham R, Lescar J, Ng ML. Inhibition of West Nile virus entry by using a recombinant domain III from the envelope glycoprotein. J Gen Virol. 2005;86:405–412. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80411-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clore GM, Gronenborn AM. Multidimensional heteronuclear nuclear magnetic resonance of proteins. Methods Enzymol. 1994;239:249–363. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(94)39013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornilescu G, Delaglio F, Bax A. Protein backbone angle restraints from searching a database for chemical shift and sequence homology. J Biomol NMR. 1999;13:289–302. doi: 10.1023/a:1008392405740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crill W, Roehrig JT. Monoclonal antibodies that bind to domain III of dengue virus E glycoprotein are the most efficient blockers of virus adsorption to Vero cells. J Virol. 2001;75:7769–7773. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.16.7769-7773.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duggan BM, Legge GB, Wright PE. SANE (Structure assisted NOE evaluation): An automated model-based approach for NOE assignment. J Biomol NMR. 2001;19:321–329. doi: 10.1023/a:1011227824104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrin TE, Huang CC, Jarvis LC, Langridge R. The MIDAS Display System. J Mol Graphics. 1988;6:13–27. [Google Scholar]

- Grzesiek S, Bax A. Correlating backbone amide and side-chain resonances in larger proteins by multiple relayed triple resonance NMR. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:6291–6293. [Google Scholar]

- Heinz FX, Allison SL. Structures and mechanisms in flavivirus fusion. Adv Virus Res. 2000;55:231–269. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(00)55005-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz FX, Allison SL. The machinery for flavivirus fusion with host cell membranes. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2001;4:450–455. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(00)00234-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz FX, Allison S. Flavivirus structure and membrane fusion. Adv Virus Res. 2003;59:63–97. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(03)59003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiramatsu K, Tadano M, Men R, Lai CJ. Mutational analysis of a neutralization epitope on the dengue type 2 virus (DEN2) envelope protein: monoclonal antibody resistant DEN2/DEN4 chimeras exhibit reduced mouse neurovirulence. Virology. 1996;224:437–445. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung JJ, Hsieh MT, Young MJ, Kao CL, King CC, Chang W. An External Loop Region of Domain III of Dengue Virus Type 2 Envelope Protein Is Involved in Serotype-Specific Binding to Mosquito but Not Mammalian Cells. J Virol. 2004;78:378–388. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.1.378-388.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikura M, Bax A, Clore GM, Gronenborn AM. Detection of nuclear Overhauser effects between degenerate amide proton resonances by heteronuclear three-dimensional NMR spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:9020–9022. [Google Scholar]

- John B, Plant D, Hurd RE. A simple experimental scheme using pulsed field gradients for coherence pathway rejection and solvent suppression in phase-sensitive heteronuclear correlation spectra. J Magn Reson A. 1993;101:113. [Google Scholar]

- Kanai R, Kar K, Anthony K, Gould LH, Ledizet M, Fikrig E, Koski RA, Modis Y. Crystal structure of West Nile virus envelope glycoprotein reveals viral surface epitopes. J Virology. 2006;80:11000–11008. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01735-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay LE, Kiefer R, Saarinen T. Pure Absorption Gradient Enhanced Heteronuclear Single Quantum Correlation Spectroscopy with Improved Sensitivity. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:10663–10665. [Google Scholar]

- Koradi R, Billeter M, Wuthrich K. MOLMOL: A Program for Display and Analysis of Macromolecular Structure, Institute for Molecular Biology and Biophysics. Swiss Federal Institute of Technology; Zürich, Switzerland: 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn RJ, Zhang W, Rossman MG, Pletnev SV, Corver J, Lenches E, Jones CT, Mukhopadhyay S, Chipman PR, Strauss EG, Baker TS, Strauss JH. Structure of dengue virus: Implications for flavivirus organization, maturation and fusion. Cell. 2002;108:717–725. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00660-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski RA, Rullman JAC, MacArthur MW, Kaptein R, Thornton JM. AQUA and PROCHECK-NMR: programs for checking the quality of protein structures solved by NMR. J Biomol NMR. 1996;8:477–496. doi: 10.1007/BF00228148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin B, Parrish CR, Murray JM, Wright PJ. Localization of a neutralizing epitope on the envelope protein of dengue virus type 2. Virology. 1994;202:885–890. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lok SM, Ng ML, Aaskov J. Amino acid and phenotypic changes in dengue 2 virus associated with escape from neutralisation by IgM antibody. J Med Virol. 2001;65:315–23. doi: 10.1002/jmv.2036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohr F, Ruterjans H. A new triple-resonance experiment for the assignment of backbone resonances in proteins. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:189–197. doi: 10.1007/BF00211783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandl C, Guirakhoo F, Holzmann H, Heinz FX, Kunz C. Antigenic structure of the flavivirus envelope protein E at the molecular level, using tick-borne encephalitis virus as a model. J Virol. 1989;63:564–71. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.2.564-571.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marion D, Kay LE, Sparks SW, Torchia DA, Bax A. Three-dimensional heteronuclear NMR of 15N labeled proteins. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:1515–1517. [Google Scholar]

- Modis Y, Ogata S, Clements D, Harrison SC. A ligand-binding pocket in the dengue virus envelope glycoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:6986–6991. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0832193100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modis Y, Ogata S, Clements D, Harrison SC. Structure of the dengue virus envelope protein after membrane fusion. Nature. 2004;427:313–319. doi: 10.1038/nature02165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modis Y, Ogata S, Clements D, Harrison SC. Variable surface epitopes in the crystal structure of dengue virus type 3 envelope glycoprotein. J Virol. 2005;79:1223. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.2.1223-1231.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee M, Dutta K, White MA, Cowburn D, Fox RO. NMR solution structure and backbone dynamics of domain III of the E protein of tick-borne Langat flavivirus suggests a potential site for molecular recognition. Prot Sci. 2006;15:1342–1355. doi: 10.1110/ps.051844006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay S, Kim B-S, Chipman PR, Rossman MG, Kuhn RJ. Structure of West Nile Virus. Science. 2003;302:248. doi: 10.1126/science.1089316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nybakken GE, Oliphant T, Johnson S, Burke S, Diamond MS, Fremond DH. Structural basis of West Nile virus neutralization by a therapeutic antibody. Nature. 2005;437:764–9. doi: 10.1038/nature03956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nybakken GE, Nelson CA, Chen BR, Diamond MS, Fremont DH. Crystal Structure of the West Nile Virus Envelope Glycoprotein. J Virol. 2006;80:11467–11474. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01125-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rey FA, Heinz FX, Mandl CW, Kunz C, Harrison SC. The envelope glycoprotein from tick-borne encephalitis virus at 2 Å resolution. Nature. 1995;375:291–198. doi: 10.1038/375291a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roehrig JT. Antigenic structure of flavivirus proteins. Adv Virus Res. 2003;59:141–75. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(03)59005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattler M, Schleucher J, Griesinger C. Heteronuclear multidimensional NMR experiments for the structure determination of proteins in solution employing pulsed field gradients. Prog NMR Spectrosc. 1999;34:93–158. [Google Scholar]

- Twiddy SS, Holmes EC, Rambaut A. Inferring the rate and time-scale of dengue virus evolution. Mol Biol Evol. 2003;20:122–129. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twiddy SS, Woelk CH, Holmes EC. Phylogenetic evidence for adaptive evolution of dengue viruses in nature. J Gen Virol. 2002;83:1679–1689. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-7-1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volk DE, Beasley DWC, Kallick DA, Holbrook MR, Barrett ADT, Gorenstein DG. Solution structure and antibody binding studies of the envelope protein domain III from the New York strain of West Nile Virus. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:38755–38761. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402385200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volk DE, Chavez L, Beasley DWC, Barrett ADT, Holbrook MR, Gorenstein DG. Structure of the envelope protein domain III of Omsk hemorrhagic fever virus. Virology. 2006;351:188–95. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volk DE, Lee Y-C, Li X, Barrett ADT, Gorenstein DG. 1H, 13C and 15N assignments of the Dengue-4 Envelope Protein Domain III. J Biomol NMR. 2006;36:62. doi: 10.1007/s10858-006-9048-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuister GW, Bax A. Resolution Enhancement and Spectral Editing of Uniformly 13C Enriched Proteins by Homonuclear Broadband 13C Decoupling. J Magn Reson. 1992;98:428–435. [Google Scholar]

- Wang E, Ni H, Xu R, Barrett AD, Watowich SJ, Gubler DJ, Weaver SC. Evolutionary relationships of endemic/epidemic and sylvatic dengue viruses. J Virol. 2000;74:3227–3234. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.7.3227-3234.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu K-P, Wu C-W, Tsao Y-P, Kuo T-W, Lou Y-C, Lin C-W, Wu S-C, Cheng J-W. Structural basis of a flavivirus recognized by its neutralizing antibody. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:46007–46013. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307776200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki T, Forman-Kay JD, Kay LE. 2-Dimensional NMR experiments for correlating C-13 beta and H-1-delta/epsilon chemical-shifts of aromatic residues in C-13-labeled proteins via scalar couplings. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:11054–11055. [Google Scholar]