Abstract

Low sexual assertiveness has been proposed as a possible mechanism through which sexual revictimization occurs, yet evidence for this has been mixed. In this study, prospective path analysis was used to examine the relationship between sexual refusal assertiveness and sexual victimization over time among a community sample of women. Results provide support for a reciprocal relationship, with historical victimization predicting low sexual assertiveness and low sexual assertiveness predicting subsequent victimization. The effect of recent sexual victimization on subsequent sexual assertiveness also was replicated prospectively. These findings suggest that strengthening sexual assertiveness may help reduce vulnerability to future victimization.

Keywords: revictimization, sexual assault, sexual assertiveness

A large body of research reveals that women who have experienced sexual victimization are at increased risk of being revictimized, yet the mechanisms by which revictimization occurs are not well understood (e.g., Gidycz, Coble, Latham, & Layman, 1993; Gidycz, Hanson, & Layman, 1995; Messman-Moore & Long, 2000, 2003). Identifying and understanding these mechanisms are critical to prevention. Psychological vulnerability is thought to be one of the mechanisms through which women’s risk of sexual revictimization is increased (see Messman-Moore & Long [2003] for a review). Psychological vulnerability refers to psychological or social vulnerabilities within the victim (e.g., low self-esteem, depression, anxiety, low assertiveness) that potential perpetrators are likely to identify and act upon. This study focuses on one aspect of psychological vulnerability, sexual assertiveness, because unlike depression or anxiety, assertiveness may be amenable to change through behavioral intervention. To maximize its potential for intervention, a better understanding of the relationship between sexual assertiveness and sexual victimization is needed. The purpose of this study is to examine the relationship between sexual assertiveness and sexual victimization over time.

Considering the role of assertiveness in sexual victimization has intuitive appeal. It is logical to assume that women who are low in assertiveness have a difficult time refusing unwanted sexual advances and may be targeted by aggressive men. Conversely, theories regarding the sequelae of childhood sexual abuse (CSA) and other victimization have proposed that experiences from which one is unable to escape or avoid can result in feelings of powerlessness or learned helplessness, potentially leading the victim to believe that it is impossible to avoid or prevent future victimization (Finkelhor, 1987; Peterson & Seligman, 1983). In addition to fostering psychological distress such as depression and anxiety, such powerlessness may be translated behaviorally into a lack of assertiveness in sexual situations. It may also be that the relationship between sexual victimization and assertiveness is reciprocal. That is, history of sexual victimization contributes to low sexual assertiveness, which in turn contributes to sexual revictimization and continued low assertiveness.

Despite its logical and intuitive appeal, research has failed to demonstrate a consistent relationship between sexual assertiveness and sexual victimization. There are several possible explanations for this, including inconsistencies in how assertiveness is defined and measured. Studies examining the relationship between sexual victimization and assertiveness have used different measures of assertiveness, and most of these measures have assessed general assertiveness rather than assertiveness specific to sexual situations (e.g., Rickert, Sanghvi, & Wiemann, 2002; Testa & Dermen, 1999; Zweig, Crockett, Sayer, & Vicary, 1999). However, if assertiveness is situation-specific, measures of general assertiveness may not be adequate for assessing assertiveness specific to sexual contexts (Greene & Navarro, 1998; Morokoff et al., 1997). In addition, several of the studies that have considered the role of assertiveness in sexual revictimization have looked at assertiveness as part of a larger constellation of psychological or interpersonal adjustment, combining it with measures of depression and social problems and thereby obscuring the unique contribution of assertiveness to sexual victimization (e.g., Classen, Field, Koopman, Nevill-Manning, & Spiegel, 2001; Gidycz et al., 1995; Mandoki & Burkhart, 1989).

Another limitation of previous research is reliance on the use of cross-sectional designs, making it difficult to determine whether low assertiveness follows from or precedes sexual victimization. For example, Testa and Dermen (1999) found that experiencing verbal sexual coercion, but not rape, was associated with lower assertiveness. They suggested that women who are low in assertiveness may be more vulnerable to being talked into having unwanted sex, whereas assertiveness is less relevant in situations where a man uses physical force to obtain sex. However, they acknowledge that because the women’s assertiveness prior to victimization was not assessed, it is impossible to know whether the low assertiveness associated with experiencing verbal sexual coercion precedes or follows from a victimization experience.

To determine whether sexual victimization has an adverse effect on subsequent sexual assertiveness or whether it follows from being low in sexual assertiveness, a prospective design is needed. To date, there are only two prospective studies examining the relationship between assertiveness and sexual victimization over time. Both of these studies included samples of college women followed over the course of an academic year, and both used path analyses to examine the links among sexual victimization experiences. The first followed college women for four assessment points over a 9-month period (baseline, 3 months, 6 months, and 9 months) and examined potential mediators of revictimization including psychological adjustment (depression and anxiety), interpersonal functioning (sociability and assertiveness), alcohol use, and number of partners (Gidycz et al., 1995). Assertiveness was not examined directly; rather it, along with a measure of sociability, was used to comprise the interpersonal functioning variable. Gidycz et al. (1995) found that adolescent victimization, but not CSA, predicted baseline interpersonal problems (including being low in assertiveness), alcohol use, and number of sexual partners. Previous victimization predicted subsequent victimization at all time points; however, interpersonal functioning failed to predict any subsequent victimization.

Greene and Navarro (1998) expanded upon Gidycz et al.’s (1995) study by focusing on assertiveness in situations with members of the opposite sex. They argued that assertiveness is situation-specific and, as such, assertiveness with members of the opposite sex is more likely to play a role in sexual victimization than is general assertiveness. Greene and Navarro assessed college women’s sexual victimization, assertiveness with the opposite sex, alcohol use, number of sexual partners, and adjustment (depression and anxiety) at three time points (the beginning of the fall semester and end of the fall and spring semesters). Consistent with Gidycz et al. (1995), they found that adolescent victimization, but not CSA, predicted baseline assertiveness with the opposite sex. In contrast, Greene and Navarro found that along with previous sexual victimization, sexual assertiveness consistently predicted subsequent sexual victimization at all time points. These findings suggest that it is assertiveness specific to sexual situations, rather than general assertiveness, that mediates between previous and subsequent sexual victimization and that the relationship between sexual assertiveness and sexual victimization is reciprocal.

Although Greene and Navarro’s (1998) findings provide support for the reciprocal relationship between sexual victimization and sexual assertiveness, more research is needed to replicate and test these relationships. The preceding prospective studies used college samples to examine the relationship between assertiveness and sexual victimization. Use of a different sample may yield different results. For example, when validating their measure of sexual assertiveness, Morokoff et al. (1997) found that history of victimization predicted low sexual refusal assertiveness (SRA) in a college sample, but not in a sample of volunteers recruited from the community. The current study seeks to replicate and extend Greene and Navarro’s research in several ways. First, in addition to examining the effects of historical sexual victimization on baseline sexual assertiveness, we also examined the impact of later sexual victimization on subsequent sexual assertiveness using a prospective design. Next, sexual assertiveness was assessed using a more refined measure of sexual assertiveness, the Sexual Refusal sub-scale of Morokoff et al.’s (1997) Sexual Assertiveness Scale. This measure specifically assesses women’s willingness to refuse unwanted sexual advances. Also, because sexual victimization is a relatively infrequent event in an individual’s life, a longer time interval (2 years) was used to allow for the inclusion of a greater number of unwanted sexual experiences and more opportunity to examine changes in sexual assertiveness over time. Finally, a randomly selected community sample of women was used to determine whether the hypothesized relationships hold in a more representative sample, thereby improving generalizability of the results.

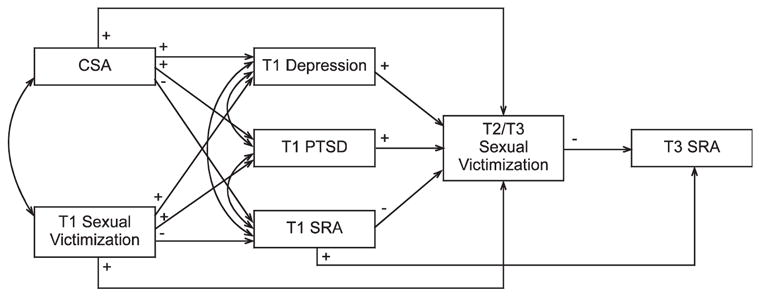

This study examined the relationship between sexual victimization and SRA at three time points over a 2-year period. We were specifically interested in determining whether history of sexual victimization influences sexual assertiveness, whether sexual assertiveness mediates the relationship between previous and subsequent sexual victimization, and how recent victimization effects subsequent sexual assertiveness. We hypothesized that (a) having a history of sexual victimization at baseline (T1) will be negatively associated with T1 sexual assertiveness; (b) being low in T1 sexual assertiveness will predict subsequent victimization, assessed at Time 2 (T2) and Time 3 (T3); and (c) T2 and T3 sexual victimization will be negatively associated with subsequent sexual assertiveness assessed at T3 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Full Path Model

Note: Full hypothesized model examining the reciprocal relationships between sexual victimization and sexual assertiveness, controlling for Time 1 (T1) depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms. The expected direction of the relationships is indicated with plus or minus sign. CSA = childhood sexual abuse; SRA = sexual refusal assertiveness.

Method

Sample

Women 18 to 30 years of age living in Buffalo, New York (n = 1,014) and its immediate suburbs in Erie County were identified using random digit dialing between May 2000 and April 2002 and recruited to participate in a prospective study on women’s social experiences. Age and proficiency with spoken English were the only eligibility criteria. In-person interviews were completed with 61% of eligible women identified, a rate that is comparable or superior to completion rates for surveys that were conducted solely by telephone (e.g., Greenfield, Graves, & Kaskutas, 1999; Welte, Barnes, Wieczorek, Tidwell, & Parker, 2001). The sample matched closely the characteristics of the local population. For example, 75% of the sample was White and 17% was African American, compared to 72% and 21%, respectively, for the geographic area from which the sample was drawn. Also consistent with local demographics, median household income for the sample was between $30,000 and $40,000, and 95% were high school graduates (compared to 89% of 18- to 34-year-old women in Erie County). At Time 1, average age was 23.76 (SD = 3.71), and most were unmarried (76% never married, 3% divorced or legally separated).

Of the original sample of 1,014 women, 87 (8.6%) women did not complete T2 or T3 or both. These noncompleters differed from completers in terms of race, with only 5.7% of Whites being noncompleters, but 16.5% of non-Whites being non-completers (χ2 = 28.63, p < .001). However, the two groups did not differ in terms of income, marital status, CSA, adolescent/adult sexual victimization, depression symptoms, alcohol and drug abuse/dependence, PTSD symptoms, age, SRA, or sexual risk behavior. Only data from the 937 women who completed all three waves of data collection were included in this analysis.

Procedure

Eligible women were asked to participate in a longitudinal study of women’s social experiences, consisting of three waves of data collection, 12 months apart. Initial participation involved a 2-hour session conducted at the Research Institute on Addictions (RIA), for which they were paid $50. Women were told that the session would include computer-administered questionnaires and a face-to-face confidential interview involving personality, alcohol and drug use, and sexual experiences. Upon arrival at RIA, study procedures were explained and informed consent was obtained. At baseline (T1), all questionnaire data used in the current study were collected using a computer-assisted self-interview (CASI).

Time 2 and Time 3 data were collected using paper-and-pencil questionnaires that were similar to measures used in the T1 CASI interview but that focused on the past 12 months rather than lifetime. T2 questionnaires were mailed to participants’ homes 12 months after the initial interview and returned by postage-paid envelope. The same procedure was followed for T3 questionnaires 12 months later. Women were sent a $50 check upon receipt of the completed questionnaire booklets. Of the original sample of 1,014 women, 972 (95.9%) completed T2 and 937 (92.4%) completed T3.

Measures

Childhood Sexual Abuse

Eight items adapted from Finkelhor (1979) and Whitmire, Harlow, Quina, and Morokoff (1999) were used to assess unwanted childhood sexual experiences at Time 1. Respondents indicated whether they had experienced the following before age 14 without their consent: a person kissing or hugging in a sexual way; touching another’s genitals at their request; a person attempted to touch in a sexual way; a person touched in a sexual way; attempted sexual intercourse; completed oral, anal, or vaginal intercourse; other vaginal or anal penetration; or other unwanted sexual experiences.

T1 Sexual Victimization Since Age 14

At T1, women completed a modified 11-item version of the Sexual Experiences Survey (SES; Koss, Gidycz, & Winiewski, 1987), which included an additional item regarding rape while incapacitated (Testa, VanZile-Tamsen, Livingston, & Koss, 2004). This behaviorally specific measure assesses a range of sexual victimization experiences occurring since age 14. A positive response to any item results in being classified as having experienced some type of sexual victimization. Women were categorized according to the most severe type of victimization experienced (Breitenbecher & Gidycz, 1998): no victimization (0), contact (1), sexual coercion (2), attempted rape (3), and rape (4). At T1, the SES was administered via CASI.

Recent Sexual Victimization

At T2 and T3, a paper-and-pencil version of the SES described above was administered to assess sexual aggression experiences occurring in each of the previous 12 months. Because incidence of sexual victimization is low within a given year, T2 and T3 victimization was combined to create a recent victimization variable (n = 166; T2 only = 72, T3 only = 50, both T2 and T3 = 44). When an individual had victimization at both T2 and T3, recent victimization was coded according to the most severe victimization experience reported. Recent sexual victimization was represented on the same 5-point severity scale (0–4) as T1 sexual victimization.

Sexual Assertiveness

Sexual assertiveness was measured using the Sexual Assertiveness Scale (SAS; Morokoff et al., 1997). This scale is made up of three subscales: Initiation Assertiveness, Pregnancy/STD Prevention Assertiveness, and Refusal Assertiveness. This measure has good validity and reliability (see Morokoff et al., 1997). Only the Refusal Assertiveness subscale was used in these analyses, because it is the most relevant to sexual victimization. This scale consists of six items such as “I refuse to have sex if I don’t want to, even if my partner insists,” which women rate on a Likert scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), with higher scores indicating more assertiveness (α = .77). SRA was measured at T1 and T3. Due to space limitations in the questionnaire, sexual assertiveness was not assessed at T2.

Depression

A measure of depressive symptoms was adapted from those used in the National Women’s Study (Duncan, Saunders, Kilpatrick, Hanson, & Resnick, 1996) and the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS; Robins, Helzer, Cottler, & Goldring, 1989). Items are consistent with diagnostic symptoms as per the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Initially, respondents were asked, “Have you ever had a period of at least two weeks when you lost interest in most things or got no pleasure from things which would usually make you happy?” and “Have you ever had at least two weeks when nearly every day you felt sad, depressed, or empty most of the time?” Those who responded “yes” to one or both of these questions were then asked whether they had experienced symptoms such as changes in appetite, significant weight loss or gain, changes in sleep patterns, difficulty concentrating, feeling low in energy, and feelings of guilt or worthlessness during that time. Questions were closed-ended with specific response metrics to facilitate use as a self-administered questionnaire (Duncan et al., 1996). At T1, those indicating they had experienced symptoms were asked the age of initial onset of the symptoms and the time of the most recent episode (ranging from more than 1 year ago to within the past month). Past year and current (past month) depressive symptoms were assessed at T2 and T3. Higher counts represent more problems related to depression.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

PTSD symptoms were assessed using the National Women’s Study PTSD Module (Acierno, Resnick, Kilpatrick, Saunders, & Best, 1999; Duncan et al., 1996), a DIS-based structured interview with a behaviorally specific, sensitive trauma screen. Respondents were asked to indicate whether they had ever had any of the experiences presented on a list of six potentially traumatic life events such as being in a serious accident, natural disaster, or any other incident in which they had been or feared being physically harmed or killed. This was done to determine whether respondents met Criterion A of the DSM-IV PTSD diagnosis, which states that the person must have been exposed to a potentially traumatic event. Those who responded “yes” to any of the six items, or who had reported experiencing a completed or attempted rape on the SES, were then asked whether they had experienced any of 21 DSM-IV PTSD symptoms. Examples of symptoms include having unpleasant memories, having repeated bad dreams or nightmares, being hypervigilant, and feeling anxious. Higher symptom counts are representative of more PTSD-related problems. Consistent with National Women’s Study PTSD Module (see Duncan et al., 1996), respondents were not required to link their symptoms to a specific traumatic event. At T1 lifetime and current PTSD symptoms were measured; at T2 and T3, potentially traumatic life events and PTSD symptoms were assessed for the past 12 months.

Data Analysis

Prospective path analysis was used to examine the relationship between sexual assertiveness and victimization over time. The path model of the hypothesized relationships was tested using AMOS (Arbuckle, 2003) with maximum likelihood estimation. Models are viewed as empirically adequate if they result in fit indices of .95 or greater (Chou & Bentler, 1995), a root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) less than .08, and medium (.13 to .25) or large (greater than .25) effect sizes as measured by R2 (Hu & Bentler, 1998).

The Path Model

The path model used to specify the proposed relationship between sexual victimization and sexual assertiveness over time is presented in Figure 1. History of sexual victimization is represented by two variables, severity of CSA and T1 sexual victimization since age 14 years (r = .23, p < .01). According to the model, history of sexual victimization is expected to have a direct negative effect on T1 SRA, such that women with a history of victimization are lower in T1 SRA. CSA and T1 sexual victimization have been entered together on the first step because both temporally precede the reporting of T1 SRA. CSA and T1 sexual victimization are expressed in terms of severity because there is evidence to suggest that more severe victimization experiences are more likely to result in adverse consequences (Browne & Finkelhor, 1986). Based on the most severe type of victimization, CSA severity was scored as 0 (no victimization), 1 (touch), or 2 (penetration or attempted penetration). T1 sexual victimization also is scored on a severity continuum of 0 (no victimization), 1 (contact), 2 (verbal coercion), 3 (attempted rape), or 4 (rape).

The second step of the model examines the effect of T1 SRA on subsequent sexual victimization, controlling for T1 depression and PTSD symptoms. Sexual victimization was assessed over the 2-year follow-up period of the study. Because research suggests that depression and PTSD are aspects of psychological vulnerability that also have been associated with experiencing sexual victimization (e.g., Finkelhor, 1987; Gidycz et al., 1995; Messman-Moore & Long, 2003), we controlled for T1 PTSD and depression symptom counts in this analysis. On the final step of the model, T2/T3 combined sexual victimization was used to predict T3 SRA. Although several studies have shown lower assertiveness among those with a history of sexual victimization, none has examined the effects of victimization on assertiveness prospectively.

Results

Sexual Victimization

A brief description of the types and frequency of sexual victimization reported as CSA, T1 sexual victimization since age 14, and recent sexual victimization are presented in Table 1. Approximately 30% (n = 289) of the sample experienced some type of sexual abuse involving sexual touching or penetration before the age of 14. At the time of the first interview (T1), 38% (n = 355) of the sample reported at least one unwanted sexual experience occurring since the age of 14. A total of 166 women reported sexual victimization over the course of the 2-year follow up.

Table 1.

Reported Sexual Victimization by Severity

| Variable (Value) | N (937) | % of Total | % of Victimized |

|---|---|---|---|

| Childhood sexual abuse (CSA) | |||

| No CSA (0) | 648 | 69.2 | 0 |

| Touch (1) | 154 | 16.4 | 53.3 |

| Penetration (2) | 135 | 14.4 | 46.7 |

| Time 1 (T1) sexual victimization since age 14 | |||

| No victimization (0) | 582 | 62.1 | 0 |

| Contact (1) | 65 | 6.9 | 18.3 |

| Verbal coercion (2) | 86 | 9.2 | 24.2 |

| Attempted rape (3) | 43 | 4.6 | 12.1 |

| Rape (4) | 161 | 17.2 | 45.4 |

| Recent sexual victimization (T2 and T3 combined) | |||

| No victimization (0) | 771 | 82.3 | 0 |

| Contact (1) | 37 | 3.9 | 22.3 |

| Verbal coercion (2) | 87 | 9.3 | 52.4 |

| Attempted rape (3) | 11 | 1.2 | 6.6 |

| Rape (4) | 31 | 3.3 | 18.7 |

Because we were interested in revictimization, we examined whether women who had experienced historical victimization were more likely than those who did not to report victimization at later time points. Women who experienced CSA were more likely than those without CSA to report T1 sexual victimization since age 14 (53% vs. 31%, χ2 = 40.25, 1, p < .01) and to report sexual victimization over the 2-year follow-up period (23.5% vs. 15.1%, χ2 = 9.69, 1, p < .01). Women who experienced T1 sexual victimization also were more likely than those who had not to report T2 or T3 sexual victimization (26.8% vs. 12.2%, χ2 = 32.07, 1, p < .01). Of the 166 women who reported victimization at T2 and T3, the majority had (70%) had a history of previous sexual victimization. There was a small number of women (n = 47) who reported CSA, T1 sexual victimization, and revictimization over the 2-year follow-up.

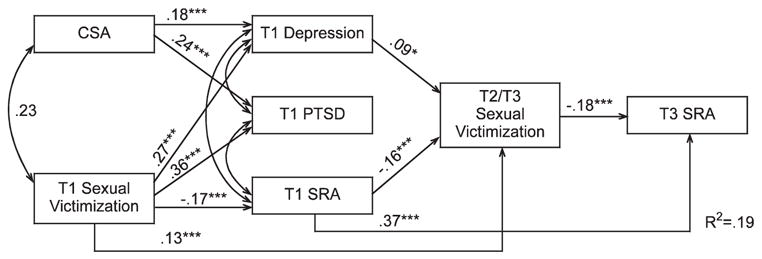

Path Analysis

Table 2 presents the means, standard deviations, and correlations for the variables included in the model. All possible paths were tested, and nonsignificant paths were trimmed from the model for ease of presentation. The full model with all proposed paths is presented in Figure 1; the trimmed model showing only significant paths is presented in Figure 2. Results are described in more detail below. The fit of the trimmed model did not differ significantly from that of the full model. Results indicate that the model was a good fit to the data (χ2 = 4.65, df = 8, p = .79; normed fit index = .99, comparative fix index = 1.0; RMSEA = .001), with a medium effect size (R2 = .19).

Table 2.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations of Variables in Model

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Childhood sexual abuse (CSA) | 0.45 | 0.73 | — | ||||||

| Time 1 (T1) sexual victimization | 1.08 | 1.56 | .23* | — | |||||

| T1 depression | 3.20 | 2.73 | .24* | .31* | — | ||||

| T1 post-traumatic stress disorder | 6.84 | 6.81 | .32* | .41* | .52* | — | |||

| T1 sexual refusal assertiveness | 3.82 | 0.69 | −.09* | −.17* | −.17* | −.11* | — | ||

| Recent sexual victimization | 0.39 | 0.95 | .07* | .19* | .16* | .12* | −.20* | — | |

| T3 SRA | 3.76 | 0.74 | −.08* | −.11* | −.09* | −.08** | .41* | −.25* | — |

p < .05.

p < .01.

Figure 2.

Trimmed Model

Note: Trimmed model of significant paths between sexual victimization and sexual assertiveness. Standardized regression coefficients are displayed. T1 = Time 1; CSA = childhood sexual abuse; SRA = sexual refusal assertiveness.

*p < .05. ***p < .001.

Effects of History of Sexual Victimization on T1 Sexual Refusal Assertiveness

Based on theory stating that victimization can result in feelings of powerlessness or learned helplessness that can affect an individual’s beliefs about the efficacy of resistance (Finkelhor, 1987; Peterson & Seligmen, 1983), we hypothesized that having a history of sexual victimization (CSA and T1 sexual victimization) would be negatively associated with T1 SRA. As the first step in this model, history of sexual victimization variables were used to predict T1 SRA, depression symptom count, and PTSD symptom count. As shown in Figure 2, T1 sexual victimization since age 14 predicted T1 SRA in the expected direction (β = −.17, p < .01); however, CSA did not. Combined, history of sexual victimization accounted for 3% of the variance in T1 SRA. History of sexual victimization also predicted the control variables of T1 depression and PTSD (see Figure 2).

Effects of Sexual Refusal Assertiveness on Subsequent Sexual Victimization

One of the primary objectives of this study was to examine the influence of SRA on sexual victimization. We expected that being low in SRA at baseline would predict experiencing sexual victimization over the 2-year follow-up period, even after controlling for T1 depression and PTSD symptoms. On the second step of the model, T1 SRA, depression and PTSD symptom counts were used to predict T2/T3 sexual victimization. As expected, results indicate that T1 SRA was negatively associated with subsequent sexual victimization (β = −.16, p < .01). Of the variables in the model, victimization since age 14 (β = .13, p < .01) and sexual assertiveness were the strongest predictors of T2/T3 victimization (see Figure 2). CSA did not have a direct effect on T2/T3 sexual victimization; however, along with T1 sexual victimization, it did have an indirect effect mediated through depression. This model accounted for 7% of the variance in T2/T3 sexual victimization.

Effects of T2/T3 Sexual Victimization on T3 Sexual Refusal Assertiveness

To examine the effects of sexual revictimization on subsequent SRA, on the final step of the model T2/T3 sexual victimization was used to predict T3 SRA. We expected that, just as T1 sexual victimization predicted T1 SRA, T2/T3 victimization would predict low T3 SRA, even after controlling for T1 SRA. This hypothesis was supported (β = −.18, p < .01). Whereas T2/T3 sexual victimization was negatively associated with T3 SRA, historical victimization was not related. The final model accounted for 19% of the variance in T3 SRA.

Additional Analyses

To determine whether SRA predicted new (first time) victimization or whether it primarily mediates between past and previous victimization, two additional models were run. The first of these models compared revictimized versus never-victimized women. Fifty women who reported victimization for the first time at T2 or T3 but who had no prior history of sexual victimization were excluded from the analyses.

The pattern of results for this model was nearly identical to the one presented in Figure 2, with the exception that CSA became a significant predictor of T1 SRA (β = −.07, p < .05), and T2/T3 sexual victimization (β = .08, p < .05). This model accounted for 17% of the variance in T3 SRA. In the second model, history of sexual victimization was removed from the model and revictimized women (n = 116) were excluded from the analysis to compare recently first-time victimized women (at T2/T3) to never-victimized women. The same pattern of results emerged, with the paths from T1 SRA to T2/T3 sexual victimization (β = −.15, p < .01) and from T2/T3 sexual victimization to T3 SRA (β = −.20, p < .01, R2 = .26) remaining significant in the predicted directions. These results show that SRA mediates between previous and subsequent revictimization as well as predicts new sexual victimization in this community sample of women.

Discussion

The results of this study show support for a reciprocal relationship between sexual victimization and sexual assertiveness. Consistent with hypotheses, women with a history of sexual victimization, particularly T1 sexual victimization since age 14, reported more difficulty refusing unwanted sexual advances. This is consistent with theories regarding the sequelae of victimization, which hold that victimization experiences can have a negative impact on women’s beliefs about their rights or ability to refuse unwanted sex (Finkelhor, 1987; Morokoff et al., 1997; Peterson & Seligman, 1983). As hypothesized, SRA also predicted subsequent sexual victimization, with women who were low in SRA being more likely to experience victimization. Thus, women who reported having difficulty refusing sexual advances were indeed more vulnerable to sexual victimization. A unique aspect of this study was the use of a prospective design that allowed us to examine the effects of T2/T3 victimization on subsequent SRA. Like historical victimization, T2/T3 sexual victimization had a negative impact on subsequent sexual assertiveness, even after controlling for baseline sexual assertiveness. Thus, we were able to replicate the victimization to assertiveness relationship prospectively, increasing confidence that victimization experiences alter women’s sexual assertiveness.

Consistent with the results of Greene and Navarro (1998) and Gidycz et al. (1995), CSA did not predict SRA. It is unclear as to why adolescent/early adult sexual victimization (assessed at T1) predicted T1 SRA, whereas CSA did not. Furthermore, while T1 sexual victimization predicted T1 SRA, its effects on T3 assertiveness were mediated through T2/T3 sexual victimization. It appears from these results that the effects of sexual victimization on assertiveness dissipate over time, so that assertiveness is most affected by more recent experiences. This is true of other victimization-related sequelae. For example, Maker, Kemmelmeier, and Peterson (2001) found that trauma from more recent sexual victimization had a greater impact on psychosocial functioning than did more distal CSA. It is also possible that the effects of victimization are cumulative, such that experiencing CSA or adolescent/early adult sexual victimization alone may not impact assertiveness, but being revictimized may further contribute to one’s sense of powerlessness and adversely affect subsequent sexual assertiveness.

Sexual assertiveness is clearly not the only mechanism through which sexual revictimization occurs. T1 sexual victimization since age 14 remained a significant predictor of recent sexual victimization, with its effects being only partially mediated by T1 SRA. We acknowledge that other potential contributors need to be considered as well. In this study, we focused on sexual assertiveness while controlling for other psychological vulnerabilities to isolate its unique effect on subsequent victimization. However, we acknowledge that behaviors, such as sexual risk behavior and substance use, may contribute to sexual victimization (see Messman-Moore & Long, 2003). Future research should examine the role of behavioral vulnerabilities in conjunction with SRA.

One of the major strengths of this study is that we were able to demonstrate the reciprocal nature of the relationship between sexual victimization and sexual assertiveness in a large, randomly selected community sample. Prior to this study, this relationship had only been observed in college samples. Other strengths include the use of a valid, reliable measure specific to SRA (SAS; Morokoff et al., 1997) and the use of a prospective design. Examining the strength of relationships over time, thereby allowing for temporal ordering, lends strength to interpretation of the results. We acknowledge, however, that the sample consisted primarily of White women who had home phones and who were stable enough to locate over the 3-year study period. More Black women than White women were lost to attrition. Thus, the relationships described here may not hold for women of different ethnicities or those we could not reach via phone. Despite this limitation, the current research contributes to the literature by providing support for the role of sexual assertiveness in sexual revictimization and provides insight into the reciprocal nature of the relationship between victimization and assertiveness.

The findings of this study have important implications for prevention. Interventions designed specifically to improve women’s ability to refuse unwanted sexual advances may help to reduce the risk of sexual victimization. Such interventions may be particularly beneficial for women who have already experienced sexual victimization, because they are likely to be low in refusal assertiveness and are at heightened risk of revictimization. Additional research is needed to examine these possibilities.

Much remains to be learned about the role of sexual assertiveness in sexual victimization. Future research should examine the processes by which sexual assertiveness, or lack thereof, contributes to sexual revictimization. We assume that women who score low in sexual assertiveness are more vulnerable to subsequent victimization, but we know little about the contexts and situations in which this occurs. For example, are low-assertive women failing to communicate their unwillingness to have sex, leading the men to mistakenly assume that they have obtained consent? Are men seeing women who are low in assertiveness as potential targets? Much also remains to be learned about the processes by which sexual assertiveness is developed. For example, the effects of victimization on SRA may be limited to those with particular characteristics such as low self-esteem or those who do not receive support following their victimization. It may also be that low sexual assertiveness may be more strongly associated with certain types of revictimization. For example, Testa and Dermen (1999) found that assertiveness was associated with verbal sexual coercion and not rape. The rates of recent sexual victimization in this study were not high enough to allow for an examination of the relationship between SRA and specific types of sexual victimization; however, this possibility should be explored in future research.

In studying the role of sexual assertiveness in predicting future sexual victimization, it is important to note that we are in no way trying to blame women for their victimization. Rather, our results highlight the serious long-term affects of victimization on women’s psychological and social well-being. Perpetrators are solely responsible for exploiting this vulnerability. The ultimate goal of sexual assault research is to empower women and reduce vulnerability.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grant R01 AA12013 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and NIH Director’s Office of Research on Women’s Health to Maria Testa. We thank Judi Callahan-Jones, Kathleen Callanan, Stacy Croff, Cassandra Hoebbel, Tiffany Holmes, Heather Neubeck, Matthew Testa, Cynthia Warthling, Kimberly Welborne, and Elizabeth Young for their assistance in recruiting, interviewing, and transcribing.

Biographies

Jennifer A. Livingston, PhD, is a project director at the Research Institute on Addictions at the University at Buffalo. Her research interests include women’s sexual behavior, substance use and sexual victimization, and adolescent risk behavior.

Maria Testa, PhD, is a senior research scientist at the Research Institute on Addictions at the University at Buffalo. Her research interests focus on women’s sexual behaviors and sexual and physical victimization, with particular emphasis on the impact of substance use in these experiences. She is currently the recipient of several NIAAA-funded grants examining the role of alcohol in women’s sexual risk behaviors and sexual assault experiences.

Carol VanZile-Tamsen, PhD, is a data manager and statistician at the Research Institute on Addictions at the University at Buffalo. Her research interests include the role of cognitive factors in women’s behavioral and emotional responses to sexual assault.

References

- Acierno R, Resnick H, Kilpatrick DG, Saunders B, Best CL. Risk factors for rape, physical assault, and posttraumatic stress disorder in women: Examination of differential multivariate relationships. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1999;13:541–563. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(99)00030-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. AMOS (Version 5) Chicago: SmallWaters Corporation; 2003. Computer software. [Google Scholar]

- Breitenbecher KH, Gidycz CA. An empirical evaluation of a program designed to reduce the risk of multiple sexual victimization. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1998;13:472–488. [Google Scholar]

- Browne A, Finkelhor D. Impact of child sexual abuse: A review of the research. Psychological Bulletin. 1986;99:66–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou C-P, Bentler PM. Estimates and tests in structural equation modeling. In: Hoyle RH, editor. Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications. London: Sage; 1995. pp. 37–55. [Google Scholar]

- Classen C, Field NP, Koopman C, Nevill-Manning K, Spiegel D. Interpersonal problems and their relationship to sexual revictimization among women sexually abused in childhood. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2001;16:495–509. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan RD, Saunders BE, Kilpatrick DG, Hanson RF, Resnick HS. Childhood physical assault as a risk factor for PTSD, depression, and substance abuse: Findings from a national survey. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1996;66:437–448. doi: 10.1037/h0080194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D. Sexually victimized children. New York: Free Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D. The trauma of child sexual abuse: Two models. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1987;2:348–366. [Google Scholar]

- Gidycz CA, Coble CN, Latham L, Layman MJ. Sexual assault experience in adulthood and prior victimization experiences: A prospective analysis. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1993;17:151–168. [Google Scholar]

- Gidycz CA, Hanson K, Layman MJ. A prospective analysis of the relationships among sexual assault experiences: An extension of previous findings. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1995;19:5–29. [Google Scholar]

- Greene DM, Navarro RL. Situation-specific assertiveness in the epidemiology of sexual victimization among university women: A prospective path analysis. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1998;22:589–604. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield TK, Graves KL, Kaskutas LA. Long-term effects of alcohol warning labels: Findings from a comparison of the United States and Ontario, Canada. Psychology & Marketing. 1999;16:261–282. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underpara-meterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods. 1998;3:424–453. [Google Scholar]

- Koss M, Gidycz CA, Wisniewski N. The scope of rape: Incidence and prevalence of sexual aggression and victimization in a national sample of higher education students. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1987;55:162–170. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.55.2.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maker AH, Kemmelmeier M, Peterson C. Child sexual abuse, peer sexual abuse, and sexual assault in adulthood: A multi-risk model of revictimization. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2001;14:351–368. doi: 10.1023/A:1011173103684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandoki CA, Burkhart BR. Sexual victimization: Is there a vicious cycle? Violence and Victims. 1989;4:179–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messman-Moore TL, Long PJ. Child sexual abuse and revictimization in the form of adult sexual abuse, adult physical abuse, and adult psychological maltreatment. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2000;15:489–502. [Google Scholar]

- Messman-Moore TL, Long PJ. The role of childhood sexual abuse sequelae in the sexual revictimization of women: An empirical review and theoretical reformulation. Clinical Psychology Review. 2003;23:537–571. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(02)00203-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morokoff PJ, Quina K, Harlow LL, Whitmire L, Grimley DM, Gibson PR, et al. Sexual Assertiveness Scale (SAS) for women: Development and validation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73:790–804. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.73.4.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson C, Seligman MEP. Learned helplessness and victimization. Journal of Social Issues. 1983;2:103–116. [Google Scholar]

- Rickert VI, Sanghvi R, Wiemann CM. Is lack of sexual assertiveness among adolescent and young adult women a cause for concern? Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2002;34:178–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Helzer JE, Cottler L, Goldring E. National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule Version III–Revised (DIS-III-R) St Louis, MO: Washington University; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Dermen KH. The differential correlates of sexual coercion and rape. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1999;14:548–561. [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, VanZile-Tamsen C, Livingston JA, Koss MP. Assessment of sexual assault using the Sexual Experiences Survey: Validity and implications for research. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2004;28:256–265. [Google Scholar]

- Welte J, Barnes G, Wieczorek W, Tidwell MCO, Parker J. Alcohol and gambling pathology among U.S. adults: Prevalence, demographic patterns and comorbidity. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62:706–712. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitmire LE, Harlow LL, Quina K, Morokoff PJ. Childhood trauma and HIV. Philadelphia: Brunner/Mazel; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Zweig JM, Crockett LJ, Sayer A, Vicary JR. A longitudinal examination of the consequences of sexual victimization for rural young adult women. Journal of Sex Research. 1999;36:396–409. [Google Scholar]