Abstract

The transcription factor cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) promotes target DNA transcription in response to cellular stimulation in brain neurons. Phosphorylation of CREB is regulated by a variety of extracellular and intracellular signals. In this study, protein kinase C (PKC)-regulated CREB phosphorylation was investigated in cultured rat striatal neurons. We found that PKC activation with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) produced a rapid and transient phosphorylation of CREB. The increase in CREB phosphorylation was dose-dependent and prevented by the two PKC selective inhibitors (chelerythrine and Gö6983). Interestingly, the PMA-induced CREB phosphorylation was also blocked by a calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase inhibitor KN93 and the two mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) kinase inhibitors PD98059 and U0126, but not by a p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580. PMA activation of PKC markedly increased phosphorylation of MAPK/extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2. The protein kinase A (PKA) inhibitor H89 at a dose that completely blocked the PKA activator (8-br-cAMP)-induced CREB phosphorylation partially blocked the PMA-stimulated CREB phosphorylation. Furthermore, blockade of NMDA and AMPA glutamate receptors and L-type voltage-operated Ca2+ channels did not alter the ability of PMA to induce CREB phosphorylation. These results demonstrate that PKC is among the protein kinases that can positively modulate CREB phosphorylation in striatal neurons, and the PKC signals to CREB activation are mediated via signaling mechanisms involving multiple downstream protein kinases.

Keywords: PKA, CaMK, ERK, p38, striatum, nucleus accumbens

1. Introduction

The cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) is a transcription factor richly found in the nucleus of brain neurons, including striatal projection neurons. Upon phosphorylation on its Ser133site, pCREB together with a CREB-binding protein (CBP) binds to the Ca2+and cyclic AMP response elements (Ca2+CREs) on the promoter region of many target DNAs to facilitate their transcription [35]. A large number of genes are found to be regulated by pCREB in striatal neurons under normal and stimulated conditions, such as immediate early genes [1,19,36] and neuropeptides [1,7,8,18]. The pCREB-regulated inducible gene expression is thought to contribute to transcription-dependent adaptive changes in neural plasticity related to long-term mental illnesses derived from dysfunctional striatal neuronal activities [28].

A variety of extracellular and intracellular signals regulate CREB phosphorylation. Stimulation of Gs-protein-coupled receptors, such as dopamine D1 receptors, with direct or indirect agonists enhanced activity of the cAMP/protein kinase A (PKA) pathway and thereby increased phosphorylation of striatal CREB in vivo [19,34] and in vitro [10]. Activation of voltage- or receptor (NMDA)-gated Ca2+ channels also increased CREB phosphorylation [10,23,30], which is processed through a pathway involving Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinases (CaMKs) [4,14,33]. Intracellularly, protein kinase C (PKC) is among cytosolic kinases positively linking to CREB in various cell lines. However, in striatal neurons that express abundant PKC [43], the role of PKC in regulating CREB phosphorylation is poorly understood.

In the present study, the direct influence of PKC on CREB phosphorylation was investigated by testing the effect of the PKC activator on CREB phosphorylation. The protein kinase mechanism downstream to PKC activation was also evaluated by testing the effect of the inhibitors relatively selective for multiple protein kinases of interest on the PKC activator-induced CREB phosphorylation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Primary striatal neuronal cultures

The standardized procedure was employed in this study to generate a predominant GABAergic neuronal culture from E19 rat embryos [25,42]. Cells grew for 10-14 days before use.

2.2. Immunocytochemistry

The ABC immunocytochemistry was performed as described previously [23,24] to detect pCREB immunoreactivity in cultured cells. After drug treatment, cultures were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min. To quench endogenous peroxidase activity, the slides were incubated for 30 min in 0.6% hydrogen peroxide. Cultures were incubated with 3% normal goat serum (VECTASTAIN ELITE ABC kit, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and 0.1% bovine serum albumin (Vector) for 30 min to block non-specific staining. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against CREB, pCREB, ERK1/2, or pERK1/2 (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA) were used as primary antibodies and diluted to 1:2000 with 1% normal goat serum. The cells were treated with primary antibodies overnight at 4° C, and incubated with biotinylated secondary antibody (goat anti-rabbit IgG, 1:200, Vector) for 1 h at room temperature. The cells were then incubated with the ABC reagent avidin-biotin-horseradish peroxidase complex (Vector) for 1 h. Finally, 3,3’-diaminobenzidine (DAB, 0.25 mg/ml/0.01% H2O2/0.04% NiCl in 50 mM tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.4) containing an intensifier 0.04% nickel chloride was used as a chromagen to localize peroxidase (for 4-6 min).

2.3. Quantitative analysis of pCREB immunoreactivity

Images were acquired via a Fluor 10X objective and a CCD video camera, and transferred onto a computer monitor. Cell counting was performed in each well as described previously [23,24]. Both positive and negative staining cells were counted on the basis of a clearly visible pCREB-labeled (obviously different from the background) or not labeled nucleus, respectively. Cells with ambiguous labeling or an unidentifiable nucleus were excluded from analysis. Neurons and astrocytes were counted separately. Phenotypes of neuronal and astrocytic cells were easily identified according to their morphological characteristics. Neurons showed small (8-12 μm) or medium-sized (13-19 μm), phase-bright cell bodies with branching processes whereas astrocytes were large and flat with phase-dark, large pale nuclei (25-35 μm) and abundant and widely spread cytoplasm [22]. Five optic fields per well (one at the center and four approximately at ~1.5 mm from the four edges of the well; 800 x 800 μm each) were selected for cell counting. The total number of neurons in one optic field usually ranged from 60 - 120. The total number of positive or negative cells from five optic fields was calculated as the percentage of positive or negative cells against the total counted cells and treated as n= 1.

2.4. Drug treatments

The culture medium was replaced by HEPES-buffered salt solution (in mM: HEPES 20, NaCl 140, KCl 5, CaCl2 1.2, glucose 5.5, pH 7.4), and after 2 h incubation, cells were treated with drugs. The salt solution without Ca2+ is referred to as Ca2+-free solution. All drugs were freshly prepared with or without an aid of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Whenever DMSO was used, PBS containing the same concentration of DMSO was used as a control vehicle. Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) and 8-br-cAMP were purchased from Sigma. N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA), (S)-α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyle-4-isoxazole propionic acid (AMPA), FPL, MK801 (dizocilpine), 4-(8-methyl-9H-1,3-dioxolo [4,5-h][2,3] benzodiazepin-5-yl)-benzenamine dihydrochloride (GYKI52466), nifedipine, chelerythrine chloride, 2-(2-amino-3-methoxyphenyl)-4H-1-benzoyran-4-one (PD98058), and 1,4-diamino-2,3-dicyano-1,4-bis[2-aminophenylthio]butadiene (U0126), and SB203580 were purchased from Tocris (Ballwin, MO). H89, KN93, and 2-[1-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-5-methoxyindol-3-yl]3-(1h-indol-3-yl) maleimide (Gö6983) were purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA).

2.5. Statistics

The results are presented as mean ± SEM. The percentages of pCREB-positive cells were evaluated using a one- or two- way analysis of variance (ANOVA), as appropriated, followed by Bonferroni (Dunn) comparison of groups using least squares-adjusted means. A probability level of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Effects of the PKC activator PMA on CREB phosphorylation

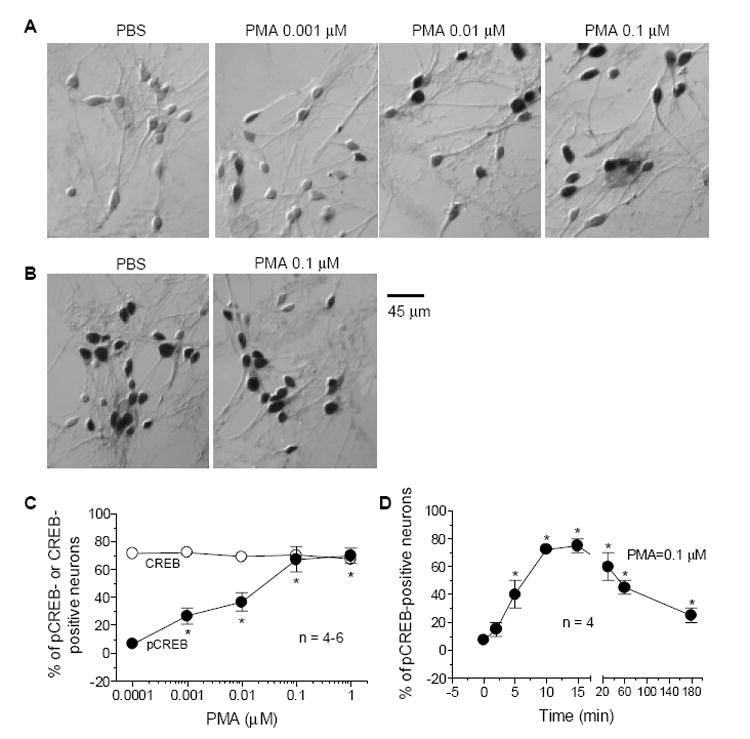

Activation of PKC with PMA at five different concentrations (10 min) caused an increase in the number of pCREB-immunoreactive neurons in striatal cultures in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1A and 1C). While few pCREB-positive neurons (< 10% of total cells) were exhibited in the culture treated with PBS, PMA at 0.001-0.01 μM started increasing the percentage of pCREB cells. A greater increase in pCREB neurons was observed at the two higher concentrations (0.1 and 1 μM). The pCREB immunoreactivity was confined to the nuclear envelope of perikarya and no specific immunostaining was seen in the neural processes and cytoplasms. In contrast to pCREB cells, total numbers of CREB-positive cells remained unchanged (Fig. 1B and 1C). To test temporal properties of the pCREB induction, we found that PMA (0.1 μM) induced an evident increase in pCREB cells after a 5-min incubation (Fig. 1D). The increased pCREB neurons peaked during 10 to 15 min incubation and gradually declined then.

Fig. 1.

Dose- and time-dependent increases in CREB phosphorylation in cultured rat striatal neurons following activation of PKC with PMA. A, Bright-field photomicrographs illustrating an increase in the number of pCREB-immunoreactive neurons following 10-min incubation of PMA at different concentrations. B, Effects of PMA (0.1 μM, 10 min) on basal CREB immunoreactivity. C and D, Quantification of numbers of pCREB- or CREB-labeled neurons after PMA incubation (10 min) at different concentrations (C) or PMA incubation (0.1 μM) for different durations. Data are the mean ± SEM of the percent change in numbers of pCREB- or CREB-positive neurons. *p< 0.05 vs. control.

3.2. Effects of the PKC, PKA, or CaMK inhibitors on the PMA-induced CREB phosphorylation

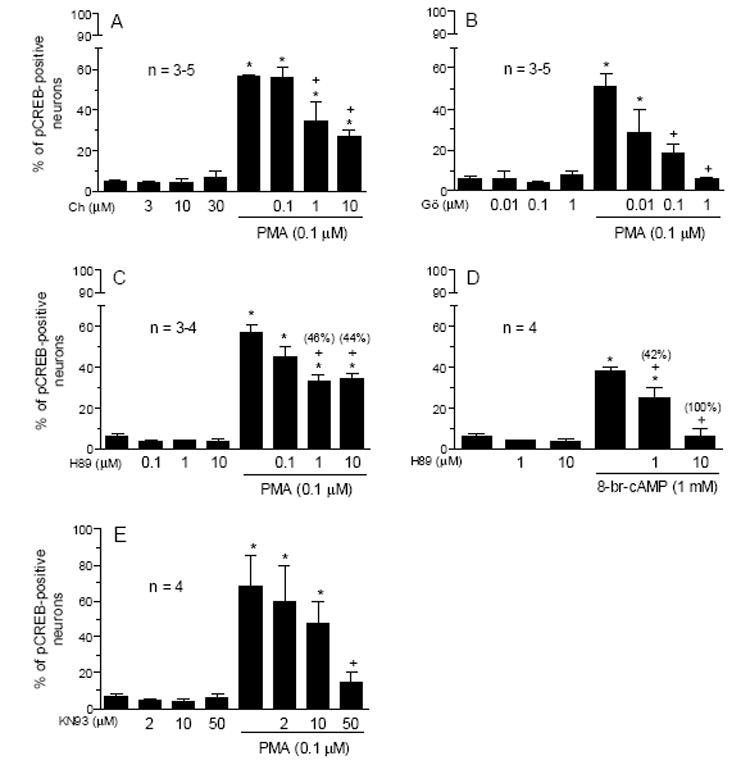

To confirm the mediating role of PKC in the PMA-induced CREB phosphorylation, the PKC inhibitor chelerythrine or Gö6983 was incubated 20 min prior to co-incubation with 0.1 μM of PMA for 10 min in cultured striatal neurons. Both chelerythrine and Gö6983 at their middle and high concentrations significantly inhibited PMA-induced increases in pCREB-labeled neurons (Fig. 2A and 2B). In the presence of a high concentration of Gö6983 (1 μM), the PMA induced-CREB phosphorylation was totally blocked (Fig. 2B). Chelerythrine or Gö6983 alone did not change basal pCREB levels (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Effects of the different protein kinase inhibitors on basal and the PMA-stimulated pCREB immunoreactivity in cultured rat striatal neurons. Chelerythrine (A), Gö6983 (B), H89 (C and D), or KN93 (E) was incubated 20 min prior to and during 10-min treatment with PMA (0.1 μM) or 8-br-cAMP (1 mM) before the fixation. The numbers in parentheses represent the degree of blockade of the activator-induced pCREB-positive neurons which were calculated according to the formula: (% value above control in the activator alone group - % value above control in H89 and activator) / % value above control in the activator alone group x 100%. Data are the mean ± SEM of the percent change in numbers of pCREB-positive neurons. *p< 0.05 vs. control, and +p< 0.05 vs. PMA or 8-br-cAMP alone.

The PKA-induced CREB phosphorylation requires PKC activity in striatal neurons [44]. To assess whether vice versa is also true, the PKA inhibitor H89 was used in this study. From Fig. 2C, H89 at 1 and 10 μM induced 46% and 44% blockade of the CREB phosphorylation induced by PMA, respectively. Consistent with the ability of H89 to block PKA activity, H89 concentration-dependently blocked the CREB phosphorylation induced by the PKA activator 8-br-cAMP (Fig. 2D).

CaMKs are the ubiquitous serine/threonine protein kinases that are activated by Ca2+ and calmodulin and have been implicated in the regulation of CREB phosphorylation [17]. To evaluate the participation of CaMKs in the PMA action, the effect of PMA was examined in the presence of the CaMK inhibitor KN93. While KN93 at a low (2 μM) or middle (10 μM) concentration did not alter the PMA effect, a high concentration (50 μM) almost completely blocked the PMA induced-CREB phosphorylation (Fig. 2E). KN92, an inactive analog of KN93, at 2-50 μM had no such effect (data not shown).

3.3. Effects of inhibition of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) on the PMA-induced CREB phosphorylation

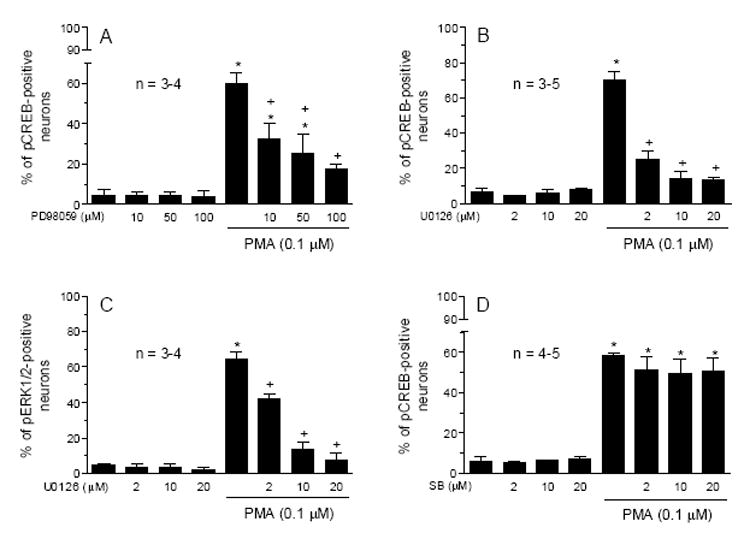

The MAPK pathway was activated by PKC in the hippocampus [31] and is an important signaling pathway activating CREB [38]. To investigate the role of MAPKs in the PMA-induced CREB phosphorylation in striatal neurons, the two inhibitors that inhibit MAPK kinase (MEK) were used. The MEK inhibitor PD98059 at all three concentrations of (10, 50 and 100 μM) significantly inhibited the pCREB increase induced by PMA, whereas PD98059 alone had no effect on basal pCREB levels (Fig. 3A). Similar results were obtained with another MEK inhibitor U0126 (Fig. 3B). Moreover, PMA (0.1 μM) induced robust phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2), a subclass of MAPKs (Fig. 3C). The pERK1/2 induction was blocked by U0126 (Fig. 3C). These results indicate that the ERK1/2 subclass of MAPKs is involved in processing the PMA activation of CREB.

Fig. 3.

Effects of the MEK inhibitors, PD98059 (A) and U0126 (B), the CaMK inhibitor KN93 (C), and the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 (D) on basal and the PMA-stimulated pCREB or pERK1/2 immunoreactivity in cultured rat striatal neurons. The inhibitors were incubated 20 min prior to and during 10-min treatment with PMA (0.1 μM) before the fixation. Data are the mean ± SEM of the percent change in numbers of pCREB- or pERK1/2-positive neurons. *p< 0.05 vs. control, and +p< 0.05 vs. PMA alone.

The contribution of another subclass of MAPKs (p38 MAPKs) was evaluated. We found that the p38 MAPK selective inhibitor SB203580 at three concentrations (2, 10, and 20 μM) did not alter the CREB phosphorylation induced by PMA (Fig. 3D). Thus, p38 MAPKs do not seem to mediate the PKC regulation of CREB phosphorylation.

3.4. Roles of glutamate receptors and L-type voltage-operated Ca2+ channels (VOCC)

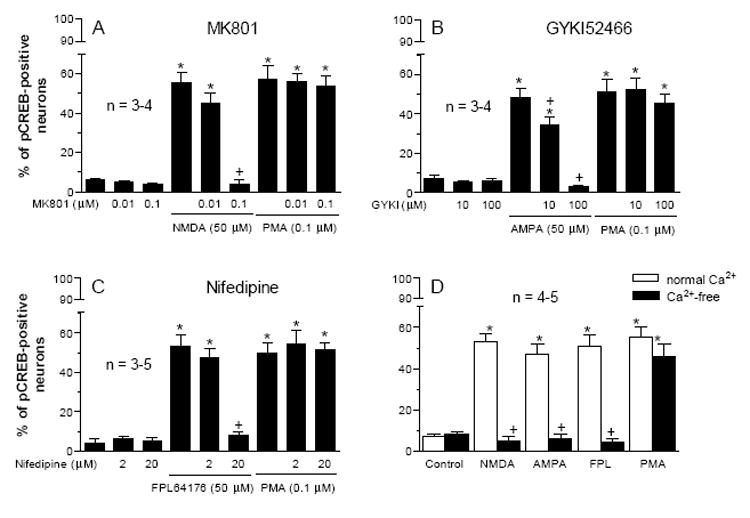

Glutamate receptors (NMDA and AMPA subtypes) and VOCCs have well been documented to increase CREB phosphorylation in striatal neurons and other cells [10,19,21,30,33]. We therefore tested whether PMA alters CREB phosphorylation through a mechanism involving activation of glutamate receptors or VOCCs. The antagonist selective for NMDA (MK801) or AMPA (GYKI52466) receptors blocked the NMDA- or AMPA-induced CREB phosphorylation, respectively, whereas the two antagonists did not affect the PMA-induced CREB phosphorylation (Fig. 4A and 4B). Similarly, the VOCC inhibitor nifedipine at a dose that blocked the VOCC activator FPL64176-stimulated CREB phosphorylation had no significant effect on the PMA-induced CREB phosphorylation (Fig. 3C). In the absence of extracellular Ca2+ ions, NMDA, AMPA and FPL64176 no longer increased CREB phosphorylation (Fig. 3D). In contrast, PMA still induced a strong phosphorylation of CREB (Fig. 3D). These results indicate a PMA effect independent of activation of NMDA and AMPA receptors and VOCCs.

Fig. 4.

Effects of the NMDA receptor antagonist MK801 (A), the AMPA receptor antagonist GYKI52466 (B), and the VOCC inhibitor nifedipine (C) on basal and the PMA-stimulated pCREB immunoreactivity in cultured rat striatal neurons. The inhibitors were incubated 20 min prior to and during 10-min treatment with PMA (0.1 μM) or their respective agonist/activator. D, effects of NMDA, AMPA, FPL64176, or PMA on the number of pCREB neurons in the presence and absence of extracellular Ca2+ ions. Data are the mean ± SEM of the percent change in numbers of pCREB-positive neurons. *p< 0.05 vs. control, and +p< 0.05 vs. NMDA (A), AMPA (B), FPL64176 (C), or the corresponding agonist in the normal Ca2+ solution (D).

4. DISCUSSION

In the present study, a series of pharmacological studies was carried out to define the role of PKC in regulating CREB phosphorylation and to dissect the downstream protein kinases and receptors responsible for this event in cultured rat striatal neurons. We found that PKC activation with PMA increased pCREB levels in striatal neurons. The increase is concentration- and time-dependent. A PKA inhibitor partially blocked the PMA effect. Moreover, the inhibitors selective for CaMK or MEK but not for p38 MAPK attenuated the PMA phosphorylation of CREB. Blockade of NMDA, AMPA and L-type VOCCs did not effect the ability of PMA to alter CREB phosphorylation. These results suggest a PKC-associated pathway upregulating CREB phosphorylation.

The PKC-regulated CREB phosphorylation was rapid and transient. This kinetics generally resembles the time course of the CREB phosphorylation in response to stimulation of other surface receptors or channels, such as dopamine (D1 or D2) receptors, glutamate receptors, and L-type VOCCs in striatal neurons or other cell lines [10,19,21,23,30]. The close temporal correlation may indicate the role of PKC in processing the CREB phosphorylation induced by stimulation of those receptors or channels. In fact, the dopamine D2 receptor agonist-induced pCREB was blocked by the PKC inhibitors [41]. NMDA receptor stimulation translocated PKC from the cytoplasm to the membrane, an active form of PKC [37], and the PKC inhibitors inhibited the NMDA-induced rise in cytosolic Ca2+ [27,39]. Together with the finding in this study that the PKC activator increased robust CREB phosphorylation, PKC may participate in the formation of an intracellular signaling pathway transmitting surface receptor/channel signals to CREB.

Cytosolic CaMKs respond to Ca2+ signals evoked by elevated Ca2+ influx through receptors (NMDA) or L-type VOCCs or by increased intracellular Ca2+ release. Activated CaMKs (mainly II isoform) then translocate into the nucleus to phosphorylate CREB [5,12,14]. In addition to responding to Ca2+ signals, CaMKs appear to respond to PKC to couple PKC to CREB. This is demonstrated by the results from this study that pharmacological blockade of CaMK activity with KN93 diminished the PKC-regulated CREB phosphorylation. It can be assumed that PKC activation leads to activation of downstream kinases, such as CaMKs, which relay the PKC signals to CREB phosphorylation.

An interesting finding in this study is the dependency of a MAPK cascade for the PKC action. The two MEK inhibitors (PD98059 and U0126) consistently blocked the PKC-regulated CREB phosphorylation. The MAPK’s role is further supported by a number of reports showing the coupling of MAPK to CREB phosphorylation [9,31,32,40]. Since the p38 MAPK inhibitor (SB203580) did not produce the same blocking effect, other subclasses of MAPKs must contribute to the PKC-CREB coupling. The ERK1/2 subclass seems to be a candidate for this event. This is because PKC possesses the ability to facilitate ERK1/2 phosphorylation in the hippocampus [13,31] and in a wide variety of cell types [6], including striatal neurons (this study). Moreover, the increased ERK1/2 activation by PKC was blocked by the MEK inhibitors PD98059 or U0126 [31; this study].

A PKA component is implicated, at least in part, in the PKC phosphorylation of CREB because a PKA inhibitor H89 partially blocked the PMA-stimulated pCREB levels. Due to limited studies, it is unclear how PKA interacts with PKC to co-stimulate CREB phosphorylation. Perhaps, PKA signals can crosstalk with any step of the PKC-to-CREB cascade to be an essential link in this event. For example, H89 attenuated the MAPK-regulated CREB phosphorylation [16,31]. Thus, PKA may join the MAPK cascade to regulate CREB phosphorylation.

A positive modulation of NMDA receptors in terms of the ligand binding, receptor trafficking and subunit phosphorylation is induced by PKC activation [15,20,29]. PKC also regulates the activity and response of AMPA and L-type VOCCs in a facilitatory manner [2,11,26]. Since NMDA and AMPA receptors and VOCCs are all capable of inducing strong CREB phosphorylation, it is likely that PKC may regulate CREB phosphorylation via activating these receptors or channels. However, the results from this study show that blockade of those surface receptors and channels had no effect on the PKC-induced CREB phosphorylation. Thus, PKC can phosphorylate CREB in a way independent of activation of these receptors and channels.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the R01 grants DA010355 (J.Q.W.) and MH061469 (J.Q.W.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Andersson M, Konradi C, Cenci MA. cAMP response element-binding protein is required for dopamine-dependent gene expression in the intact but not the dopamine-denervated striatum. J Neurosci. 2001;21:9930–9943. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-24-09930.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartschat DK, Rhodes TE. Protein kinase C modulates calcium channels in isolated presynaptic nerve terminals of rat hippocampus. J Neurochem. 1995;64:2064–2072. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.64052064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berridge MJ. Inositol triphosphate and calcium signaling. Nature. 1993;361:315–325. doi: 10.1038/361315a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choe ES, Wang JQ. Group I metabotropic glutamate receptors control phosphorylation of CREB, Elk-1 and ERK via a CaMKII-dependent pathway in rat striatum. Neurosci Lett. 2001;313:129–132. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)02258-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choe ES, Wang JQ. Regulation of transcription factor phosphorylation by metabotropic glutamate receptor-associated signaling pathways in rat striatal neurons. Neuroscience. 2002;114:557–565. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00318-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cobb MH, Goldsmith EJ. How MAP kinases are regulated. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:14843–14846. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.25.14843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cole RL, Konradi C, Douglass J, Hyman SE. Neuronal adaptation to amphetamine and dopamine: molecular mechanisms of prodynorphin gene regulation in rat striatum. Neuron. 1995;14:813–823. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90225-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collins-Hicok J, Lin L, Spiro C, Laybourn PJ, Tschumper R, Rapacz B, McMurray CT. Induction of the rat prodynorphin gene through Gs-coupled receptors may involve phosphorylation-dependent derepression and activation. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:2837–2848. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.5.2837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dalby KN, Morrice N, Caudwell FB, Avruch J, Cohen P. Identification of regulatory phosphorylation sites in mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)-activated protein kinase-1a/p90rsk that are inducible by MAPK. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:1496–1505. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.3.1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Das S, Grunert M, Williams L, Vincent SR. NMDA and D1 receptors regulate the phosphorylation of CREB and the induction of c-fos in striatal neurons in primary culture. Synapse. 1997;25:227–233. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199703)25:3<227::AID-SYN1>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daw MI, Chittajallu R, Bortolotto ZA, Dev KK, Duprat F, Henley JM, Collingridge GL, Isaac JT. PDZ proteins interacting with C-terminal GluR2/3 are involved in a PKC-dependent regulation of AMPA receptors at hippocampal synapses. Neuron. 2000;28:873–886. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00160-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deisseroth K, Heist EK, Tsien RW. Translocation of calmodulin to the nucleus supports CREB phosphorylation in hippocampal neurons. Nature. 1998;392:198–202. doi: 10.1038/32448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.English JD, Sweatt JD. Activation of p42 mitogen-activated protein kinase in hippocampal long-term potentiation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:24329–24332. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.40.24329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghosh A, Greenberg ME. Calcium signaling in neurons: molecular mechanisms and cellular consequences. Science. 1995;268:239–247. doi: 10.1126/science.7716515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grosshans DR, Browning MD. Protein kinase C activation induces tyrosine phosphorylation of the NR2A and NR2B subunits of the NMDA receptor. J Neurochem. 2001;76:737–744. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Impey S, Obrietan K, Wong ST, Poser S, Yano S, Wayman G, Deloulme JC, Chan G, Storm DR. Cross talk between ERK and PKA is required for Ca2+ stimulation of CREB-dependent transcription and ERK nuclear translocation. Neuron. 1998;21:869–883. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80602-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kapiloff MS, Mathis JM, Nelson CA, Lin CR, Rosenfeld MG. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase mediates a pathway for transcriptional regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:3710–1714. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.9.3710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kobierski LA, Wong AE, Srivastava S, Borsook D, Hyman SE. Cyclic AMP-dependent activation of the proenkephalin gene requires phosphorylation of CREB at serine-133 and a Src-related kinase. J Neurochem. 1999;73:129–138. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0730129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Konradi C, Cole RL, Heckers S, Hyman SE. Amphetamine regulates gene expression in rat striatum via transcription factor CREB. J Neurosci. 1994;14:5623–5634. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-09-05623.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lan JY, Skeberdis VA, Jover T, Grooms SY, Lin Y, Araneda RC, Zheng X, Bennett MV, Zukin RS. Protein kinase C modulates NMDA receptor trafficking and gating. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:382–90. doi: 10.1038/86028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu FC, Garybiel AM. Dopamine and calcium signal interaction in the developing striatum: control by kinetics of CREB phosphorylation. Adv Pharmacol. 1998;42:686–686. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(08)60840-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mao L, Wang JQ. Upregulation of preprodynorphin and preproenkephalin mRNA expression by selective activation of group I metabotropic glutamate receptors in characterized primary cultures of rat striatal neurons. Mol Brain Res. 2001;86:125–137. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(00)00276-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mao L, Wang JQ. Glutamate cascade to cAMP response element-binding protein phosphorylation in cultured striatal neurons through calcium-coupled group I mGluRs. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62:473–484. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.3.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mao L, Wang JQ. Phosphorylation of cAMP response element-binding protein in cultured striatal neurons by metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 5. J Neurochem. 2003;83:1–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mao L, Yang L, Tang Q, Samdani S, Zhang G, Wang JQ. The scaffold protein homer1b/c links metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 to extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase cascades in neurons. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2741–2752. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4360-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McDonald BJ, Chung HJ, Huganir RL. Identification of protein kinase C phosphorylation sites within the AMPA receptor GluR2 subunit. Neuropharmacology. 2001;41:672–679. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(01)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murphy NP, Cordier J, Glowinski J, Premont J. Is protein kinase C activity required for the N-methyl-D-aspartate-evoked rise in cytosolic Ca2+ in mouse striatal neurons? Eur J Neurosci. 1994;6:854–860. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1994.tb00995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nestler EJ, Aghajanian GK. Molecular and cellular basis of addiction. Science. 1997;278:58–63. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5335.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oh S, Jang CG, Ho IK. Activation of protein kinase C by phorbol dibutyrate potentiates [3H] MK-801 binding in rat brain slices. Brain Res. 1998;793:337–340. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00272-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rajadhyaksha A, Barczak A, Macias W, Leveque JC, Lewis SE, Konradi C. L-Type Ca(2+) channels are essential for glutamate-mediated CREB phosphorylation and c-fos gene expression in striatal neurons. J Neurosci. 1999;19:6348–6359. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-15-06348.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roberson ED, English JD, Adams JP, Selcher JC, Kondratick C, Sweatt JD. The mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade couples PKA and PKC to cAMP response element binding protein phosphorylation in area CA1 of hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1999;19:4337–4348. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-11-04337.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sgambato V, Pages C, Rogard M, Besson MJ, Caboche J. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) controls immediate early gene induction on corticostriatal stimulation. J Neurosci. 1998;18:8814–8825. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-21-08814.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sheng ME, Thompson MA, Greenberg ME. CREB: a Ca2+-regulated transcription factor phosphorylated by CaM kinases. Science. 1991;252:1427–1430. doi: 10.1126/science.1646483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simpson JN, Wang JQ, McGinty JF. Repeated amphetamine administration induces a prolonged augmentation of phosphorylated-CREB and Fos-related antigen immunoreactivity in rat striatum. Neuroscience. 1995;69:441–457. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00274-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vallejo M. Transcriptional control of gene expression by cAMP-response element binding proteins. J Neuroendocrinol. 1994;6:587–596. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.1994.tb00623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vanhoutte P, Barnier JV, Guibert B, Pages C, Besson MJ, Hipskind RA, Caboche J. Glutamate induces phosphorylation of Elk-1 and CREB, along with c-fos activation, via an extracellular signal-regulated kinase-dependent pathway in brain slices. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:136–146. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vaccarino FM, Liljequist S, Tallman JF. Modulation of protein kinase C translocation by excitatory and inhibitory amino acids in primary cultures of neurons. J Neurochem. 1991;57:391–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb03765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang JQ, Fibuch EE, Mao L. Regulation of mitogen-activated protein kinases by glutamate receptors. J Neurochem. 2006 doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04208.x. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weiss S, Hochman D, MacVicar BA. Repeated NMDA receptor activation induces distinct intracellular calcium changes in subpopulations of striatal neurons in vitro. Brain Res. 1993;627:63–71. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90749-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xing J, Ginty DD, Greenberg ME. Coupling of the RAS-MAPK pathway to gene activation of RSK2, a growth factor-regulated CREB kinase. Science. 1996;273:959–963. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5277.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yan Z, Feng J, Fienberg AA, Greengard P. D(2) dopamine receptors induce mitogen-activated protein kinase and cAMP response element-binding protein phosphorylation in neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:11607–11612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang L, Mao L, Chen H, Catavsan M, Kozinn J, Arora A, Liu X, Wang JQ. A signaling mechanism from Gαq-protein-coupled metabotropic glutamate receptors to gene expression: role of the c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathway. J Neurosci. 2006;26:971–980. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4423-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yoshihara C, Saito N, Taniyama K, Tanaka C. Differential localization of four subspecies of protein kinase C in the rat striatum and substania nigra. J Neurosci. 1991;11:690–700. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-03-00690.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zanassi P, Paolillo M, Feliciello A, Avvedimento EV, Gallo V, Schinelli S. cAMP-dependent protein kinase induces cAMP-response element-binding protein phosphorylation via an intracellular calcium release/ERK-dependent pathway in striatal neurons. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:11487–11495. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007631200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]