Abstract

This review deals with the physiology of the initiation of a voluntary movement and the appreciation of whether it is voluntary or not. I argue that free will is not a driving force for movement, but a conscious awareness concerning the nature of the movement. Movement initiation and the perception of willing the movement can be separately manipulated. Movement is generated subconsciously, and the conscious sense of volition comes later, but the exact time of this event is difficult to assess because of the potentially illusory nature of introspection. Neurological disorders of volition are also reviewed. The evidence suggests that movement is initiated in frontal lobe, particularly the mesial areas, and the sense of volition arises as the result of a corollary discharge likely involving multiple areas with reciprocal connections including those in the parietal lobe and insular cortex.

Keywords: volition, free will, movement related cortical potential, Bereitschaftspotential, decision, transcranial magnetic stimulation, consciousness, movement, agency

1.0 Introduction

While the feature of voluntariness of a voluntary movement, which is generally assumed to be initiated by the process of free will, has been usually left to the philosophers, it is now the time for physiology to deal with it. Issues such as the anatomy of the motor system, the physiology of the motor cortical regions, the spinal cord, and the motor units, the kinematics and kinetics of movement, and reflexes have been the day to day activities of physiology. There have also been strides in understanding the pathophysiology of movement: ataxia, bradykinesia, tremor, myoclonus and dyskinesias. However, physiology often skirts around the issue of voluntariness itself.

It is a common perception that humans have free will, that we choose to make our (voluntary) movements. Each person has that perception and grants a similar capacity of voluntariness to other humans. It is likely that other animals also have this capacity, but it is not known when this trait appeared during evolution. There has been no understanding of volition, however, on the physiological level. What does free will mean, and how can it be studied? As C. M. Fisher has said, “The neurologist with his special knowledge should have an opinion, or at least should be interested.”(Fisher, 1993)

Free will is intertwined with the issue of consciousness. There is some understanding about states of consciousness, waking, sleep, coma, and lesions in certain parts of the brain will impair or modify consciousness.(Zeman, 2001; Zeman, 2005) It is difficult to find something intelligent to say about consciousness itself, and philosophers agree, calling this the “hard problem”. Over the centuries, there have been two general views. Dualism is the view that the brain and the mind are separate; that scientists study the brain, but that consciousness is a feature of the mind. No evidence supports this view, and currently most people reject it. While rejecting the view scientifically, it is easy to drift back to thinking in this way. Monism is the view that mind is a product of brain. While most people accept this view, the chief problem is the lack of understanding about how this is possible.

The best definition of consciousness is “awareness.” When there is no awareness of anything, there is no consciousness. Consciousness is composed of awareness of different elements: a rose, warmth, a Beethoven symphony, love, fear, a thought, and the view that “I have chosen to make a movement”. Each element is called a “quale.”(Searle, 1998) How does the brain appreciate a quale? Is there a little man sitting somewhere in the brain, appreciating these different sensations and deciding when to move? This solution, really a form of dualism, is often called the Cartesian theater.(Baars, 1998; Dennett, 1991; Kinsbourne, 1993) This is nonsensical, of course, since there would be the same physiological problems for the little man as for the whole person. There is some understanding of the physiology of perception, but still there is a giant step between perception and awareness. It must be noted, however, that awareness is a construction of the brain, and there is no assurance that its constructions always are true reflections of reality. As Crick has written, “We are deceived at every level by our introspection.”(Crick, 1994)

Recognizing that consciousness is awareness does change the way we can approach the fundamental problem of free will. Free will can be alternatively viewed as “the awareness that we choose to make movements.” Looking at it in this way produces at least two possibilities (Fig. 1). The first is that there is a process of free will that does choose to make a specific movement. This can be called the “driving force” model. The second is that the brain’s motor system produces a movement as a product of its different inputs, consciousness is informed of this movement, and it is perceived as being freely chosen. This can be called the “perception” model. There are some good arguments in favor of the latter. There are at least two possible forms of the perceptual model, as indicated in the figure, the perception can follow the movement or be in parallel with the movement. As will be demonstrated, the data are in favor of the parallel model.

Figure 1.

Possible models of free will. The blocks indicate functional activities of regions of brain and the arrows indicate time.

2.0 Arguments in favor of free will as a perception

2.1 The brain initiates a movement before awareness of volition

The clever experiment showing that the brain initiates a movement before awareness of volition was reported by Libet et al.(Libet et al., 1983) Subjects sat in front of a clock with a rapidly moving spot and were told to move at will. Subsequently, they were asked to say what time it was (where the spot was) when they had the first subjective experience (the quale) of intending to act (this time was called W for “will”). They also were asked to specify the time of awareness of actually moving (this time was called M). There were two types of voluntary movements, one type was thoughtfully initiated and a second type was “spontaneous and capricious.” As a control for the ability to successfully subjectively time events, subjects were also stimulated at random times with a skin stimulus and they were asked to time this event (called S). At the same time, EEG was being recorded and movement-related cortical potentials (MRCPs) were assessed to determine timing of activity of the brain.

The MRCP prior to movement has a number of components.(Deecke, 1990; Jahanshahi and Hallett, 2003; Shibasaki and Hallett, 2005) An early negativity preceding movement, the Bereitschaftspotential or BP, has two phases, an initial, slowly rising phase lasting from about 1500 ms to about 400 ms before movement, the early BP or BP1, and a later, more rapidly rising phase lasting from about 400 ms to approximately the time of movement onset, late BP, BP2, or “the negative slope” (NS’). The topography of the early BP is generalized with a vertex maximum. With the late BP the negativity begins to shift to the central region contralateral to the hand that is moving. The main contributors to the early BP are the premotor cortex and the supplementary motor area (SMA), both bilaterally.(Toma et al., 2002) With the appearance of the late BP the activity of the contralateral primary motor cortex (M1) becomes prominent. With thoughtful, preplanned movements, the BP began about 1050 ms prior to EMG onset (the type I of Libet), and with more spontaneous movements, the BP began about 575 ms prior to movement (the type II of Libet).(Libet et al., 1982) The MRCP is a direct measure of activity in the brain that is related to the genesis of movement.

Subjects were reasonably accurate in determining the time of S indicating that this method of timing of subjective experience was acceptable. W occurred about 200 ms prior to EMG onset and M occurred about 90 ms prior to EMG onset. The onset of the BP type I occurred about 850 ms prior to W, and the onset of the BP type II occurred about 375 ms prior to W (Fig. 2). The authors concluded “that cerebral initiation of a spontaneous, freely voluntary act can begin unconsciously, that is, before there is any (at least recallable) subjective awareness that a ‘decision’ to act has already been initiated cerebrally.”(Libet, Gleason et al., 1983)

Fig. 2.

Timing of subjective events and the Bereitschaftspotential (readiness potential, RP) with data from Libet et al. (1983). RPI is the onset of the Bereitschaftspotential with ordinarily voluntary movements and RPII is the onset with movements made quickly with little forethought. W is the subjective timing of the will to move, M is the subjective timing of the onset of movement, S is the subjective timing of a shock to the finger. EMG onset or shock delivery is set at zero ms.

These results have been reproduced by many others, so the basic data are really not in question. Haggard and Eimer looked carefully at the timing of W compared with BP onset and the onset of another measure, the lateralized readiness potential (LRP, the difference in the voltage of right and left central regions) in tasks where subjects moved either their right or left hands.(Haggard and Eimer, 1999) The LRP timing was similar to the late BP component indicating the onset of asymmetry of the cortical activity relating to the hand that will eventually move. The onset of the LRP preceded W. Across subjects they found a better relationship between the timing of the onset of the LRP and W than between the onset of the BP and W, and suggested that the “processes underlying the LRP may cause our awareness of movement initiation.” This work suggested that movement selection also precedes awareness.

In other work, Haggard et al. looked at the timing of M with respect to movement in more detail.(Haggard et al., 1999) They looked at M in relation to the initiation of sequences of movements of various lengths. Sequences of longer length take a longer time to prepare for execution. In such circumstances, M occurs more in advance of the first movement of the sequence. This implies that the awareness of actions is associated with “some pre-motor event after the initial intention and preparation of action, but before the assembly and dispatch of the actual motor command to the muscles”.

2.1.1 Criticisms of the “Libet clock” experiment

This section is an aside from the main argument, but is necessary since the interpretation of the data from the Libet clock experiments has been subject to much discussion and criticism. One issue is what really designates the intention to move. It could be argued that the decision to move is made when agreeing to do the experiment in the first place.(Deecke and Kornhuber, 2003; Mele, 2006; Mele, 2007) The movements themselves are then a simple consequence of that earlier choice. Libet himself argued that his results did not invalidate the concept of free will. His view was that the movement was indeed initiated subconsciously, but subject to veto once it reached consciousness.(Libet, 1999; Libet, 2006) This veto power should be considered free will. This is a somewhat unusual way of looking at the issue, and this power has been designated “free won’t”.(Obhi and Haggard, 2004) Of course, “free won’t” could also be initiated subconsciously and could be basically the same process as free will. For example, there is a cortical potential prior to relaxation of a tonic movement that is similar to the Bereitschaftspotential.(Terada et al., 1995a)

Another type of concern is the nature of subjective time and its variable relationship to real time.(Eagleman et al., 2005) One aspect of this is that the subjective present is actually slightly in the real past. It takes time for sensory information to reach the brain, and these times are variable for different types of input. There has to be time to allow this information to be aligned for a unitary percept. Several experiments reveal some of the features of subjective time. In the flash-lag illusion, a flash is given together with a moving object in the same location. However, the moving object is seen to be where the moving object is approximately 80 ms after the flash. This appears to be due to a process of postdiction where the percept attributed to a specific time is modulated by what happens in the subsequent 80 ms.(Eagleman and Sejnowski, 2000) If someone presses a key regularly and sees a resultant flash at a particular interval, they get sufficiently linked such that if the key press to flash interval is shortened, persons get the sense that the flash occurs prior to the key press.(Stetson et al., 2006) In another experiment, persons pressed a key and then heard a tone at variable intervals. The subjective time for these two events was determined and the interval between the keypress and tone was erroneously short when the real interval was relatively short and more accurate when the interval was longer.(Haggard et al., 2002) This did not happen when the movement was caused by a TMS pulse. Hence, intention appears to bind the movement and consequence closer together.

Because of these problems with subjective time, we have approached the problem in a different way. In preliminary experiments, we asked subjects to make movements at freely chosen times while listening to tones occurring at random times.(Matsuhashi and Hallett, 2006) If a tone came after the thought to make a movement, but before the movement, the subject was to veto the movement. No introspective data are needed to interpret the data, which suggested that the time interval between intending to move and movement is longer than that of the Libet W, but still not as long as the MRCP. This experiment can be considered a study of “free won’t”.

2.2 Voluntary movements can be triggered with stimuli that are not perceived

To understand the experiments here, the phenomenon of backward masking is a prerequisite. By itself, a small stimulus is easily recognized. If the small stimulus is followed quickly by a large stimulus, then only the large stimulus is appreciated; the small one has been masked. This phenomenon is robust and has been demonstrated in the visual and tactile modes. Its physiology is not completely understood, although there is some information suggesting that there interference with early cortical processing.(Macknik, 2006; Macknik and Livingstone, 1998)

Taylor and McCloskey looked to see if voluntary movements could be triggered by backwardly masked stimuli.(Taylor and McCloskey, 1990) Large and small visual stimuli were presented to normal human subjects in two different experiments. In some trials, the small stimulus was followed 50 ms later by the large stimulus. In perception experiments, they demonstrated in this circumstance that the small stimulus was not perceived even with forced-choice testing showing the phenomenon of “backward masking.” In reaction time (RT) experiments, the RTs for responses to the masked stimulus were the same as those for responses to the easily perceived, nonmasked stimulus. Hence, subjects were reacting to stimuli not perceived. In this circumstance, the order of events was stimulus-response-perception, and not stimulus-perception-response that would seem necessary for the ordinary view of free will.

Subsequently these authors extended this work by using large and small stimuli in two visual locations that signaled two different types of movement.(Taylor and McCloskey, 1996) Large and small stimuli were presented in either location, and in some trials, the small stimulus was followed 50 ms later by the large stimulus in both locations. In this circumstance, the small stimulus was “masked” by the large stimulus and could not be perceived on forced-choice testing. Despite not perceiving the test stimulus, subjects were able to select and execute the motor response appropriate for each location. The RTs for responses to the masked stimulus and to the same stimulus presented without masking were the same. The authors concluded that “this result implies that appropriate programs for two separate movements can be simultaneously held ready for use, and that either one can be executed when triggered by specific stimuli without subjective awareness of such stimuli and so without further voluntary elaboration in response to such awareness.” In this situation, the order of events would have to be stimulus-“response selection”-response-perception.

Similar results have been obtained in experiments using weak and strong electric shock stimuli to the palm as a trigger for movement.(MacIntyre and McComas, 1996)

2.3 Sense of volition depends on sense of causality

Wegner argues that free will is an illusion derived from the relationship between one’s thought and the movement itself.(Wegner, 2002; Wegner, 2003; Wegner, 2004) The thought must occur before the movement, it must be consistent with the movement and there must not be another obvious cause for the movement. These features imply causality, that the thought led to the movement. In one experiment, they showed that subjects thought they caused an action, which was actually caused by someone else, by leading them to think about the action prior to its occurrence. (Wegner and Wheatley, 1999) The subject and an experimenter together manipulated a mouse that drove a cursor on a computer screen. The screen showed many objects. The object names were occasionally given in auditory signal to the subject followed by the experimenter stopping the cursor on the named object. Subjects often had the sense that they had decided to stop the cursor on that object; they had the perception of voluntariness, but there was no actual “voluntary” movement.

The logic here is that to have the sense of causality of volition, the perception of choice must precede the movement. That W precedes M (using the Libet terminology) is absolutely critical for people to believe that a movement is voluntary.

3.0 Introspection of voluntariness

Once the possibility of free will being a perception is considered, some other aspects of behavior might be more easily understood. One such situation, I refer to as the “salted peanut problem.” Imagine yourself sitting in front of a bowl of salted peanuts. After having eating a moderate number, you say, at least to yourself, that you have had enough and you will not eat any more. Shortly afterwards, you find your hand going toward the bowl. You might wonder: Who’s in charge? Clearly, we often do things that we do not really think that we want to do. Voluntariness may be ascribed to the movement post hoc. Fisher has described this same issue more harshly, “If there is a will, it must be flimsy judging from the commonplace of deceit and dishonesty in principled persons.” (Fisher, 1993)

Careful observation of your own behavior will reveal that movement may well occur prior to the apparent planning of the movement. If asked a question that you do not immediately know the answer, you think about it. Then, you say the answer. In this situation, when you have reacted quickly, sometimes you may well say the answer prior to recognizing that you know the answer. This is not compatible with the ordinary notion of free will where the conscious knowledge of the answer should guide the spoken response.

In general, we go through our lives making movements all the time. Some are clearly made automatically without much thought at all. Most of the time, we do not introspect about whether an action was willed or not.

4.0 Neurologic disorders of will

How should involuntary movements be interpreted? Patients with chorea often do not recognize that there are any involuntary movements early in the course of their illness. When asked about a movement, patients will say that it was voluntary. For unclear reason, their brain apparently interprets the involuntary movements as being voluntary. Patients with tics often cannot say whether their movements are voluntary or involuntary. This appears not to be a relevant distinction in their minds. It is perhaps a better description to say that they can suppress their movements or they just let them happen. Tics look like voluntary movements in all respects from the point of view of EMG and kinesiology. Interestingly, they are often not preceded by a MRCP or only a brief MRCP, and hence the brain mechanisms for their production clearly differs from ordinary voluntary movement.(Karp et al., 1996; Obeso et al., 1981) If forced to choose voluntary or involuntary, however, patients will usually say that the movements were voluntarily performed.

The symptom of loss of voluntary movement is often called abulia or, in the extreme, akinetic mutism.(Fisher, 1983) The classic lesion is in the midline frontal region affecting areas including the SMA and cingulate motor areas (CMA). Recent anatomical studies have divided the mesial frontal regions into the SMA, the pre-SMA, and rostral and caudal cingulate motor areas (CMAr, CMAc), with perhaps further division of the caudal cingulate area into the dorsal and ventral (caudal) cingulate areas (CMAd, CMAv). Which of these regions is the most critical for abulia is not yet clear. Lesions in other areas may give rise to similar symptoms including particularly the basal ganglia. The bradykinesia and akinesia of Parkinson’s disease is a symptom complex of the same type.

The alien hand phenomenon, the feeling that the hand does not belong to the person, is often characterized by unwanted movements that arise without any sense of their being willed. In addition to simple, unskilled, quasi-reflex movements (such as grasping), there can also be complex, skilled movements.(Fisher, 2000) There are a variety of movement types.(Aboitiz et al., 2003; Scepkowski and Cronin-Golomb, 2003) Diagonistic dyspraxia is where there is intermanual conflict, the left hand performs actions contrary to actions performed by the right hand. The anarchic hand, or way-ward hand, performs goal-directed movements that the person does not perceive as voluntary. The levitating hand rises up aimlessly. In these patients, there appears to be a difficulty in self initiating movement and excessive ease in the production of involuntary and triggered movements. In cases with discrete lesions, this seems to have its anatomical correlation in the corpus callosum and/or in the mesial frontal lobe, although there may be some cases due to parietal injury.(Kikkert et al., 2006; Scepkowski and Cronin-Golomb, 2003)

Psychogenic movements are movements reported by the patient to be involuntary. Their etiology has been obscure, and they are often thought to arise from a “conversion” mechanism, although the physiology of conversion is really unknown. EEG investigation of these movements show a normal looking MRCP preceding them.(Terada et al., 1995b; Toro and Torres, 1986) As noted above, patients with tics describe their movements as voluntary and there is no MRCP. Hence, the MRCP does not indicate “voluntariness”. Other evidence that the MRCP does not equate with “voluntary” comes from the observation that a normal looking MRCP can precede unconscious movements in normal subjects. This was studied by looking at the brain events preceding unrecognized movements made by subjects at rest or engaged in a mental task.(Keller and Heckhausen, 1990) The conclusion is that the MRCP indicates only a set of brain processes relating to the genesis of movement, including, but not limited to, those movements that will be interpreted as being voluntary. Tics must have an alternate process of genesis, and there is some evidence that this might be mediated in part via the insula.(Bohlhalter et al., 2006) There have been several neuroimaging studies of psychogenic paralysis that have given disparate results,(Spence et al., 2000; Vuilleumier et al., 2001) but no investigations of psychogenic movements.

Psychogenic tremor behaves in many ways like voluntary repetitive movements. A good test for psychogenic tremor is to have the patient tap with an unaffected limb at different frequencies. Often the tremor will become synchronous with the voluntary tapping, or, if not completely synchronous, it may change in frequency.(Brown and Thompson, 2001; Deuschl et al., 1998; McAuley and Rothwell, 2004; Zeuner et al., 2003) Additionally, a requested voluntary quick movement of an unaffected limb will cause a transient pause in the tremor.(Kumru et al., 2004) All these points suggest that psychogenic tremor shares a common mechanism with voluntary movement. There is no clear explanation, however, for the fact that despite this sharing, there is not a perception of willing the movement.

In patients with amputations, there can often be the phantom limb phenomenon. In this situation, patients can have the sense of moving their phantom, but there is, of course, no actual movement. Another situation where patients believe that they are making movement when none occurs is with anosognosia.(Berti et al., 2005) These situations indicate that there can be a sense of volition without feedback from an actual movement.

In schizophrenia, there is often the subjective impression of the patient that their movements are being externally (or alien) controlled. Their movements typically look normal, are goal directed, and are clearly generated by the patient’s brain, but do not get associated with a sense that the patient him or herself has willed the movement.(Frith et al., 2000) If W does not precede M in a normal fashion, then there may not be a normal sense of causality. In preliminary experiments we have demonstrated that the interval between W and M is shorter than normal in patients with schizophrenia.(Pirio Richardson et al., 2006)

There are clearly many different situations where there is a mismatch between movement and the sense of volition. It becomes easier to interpret all these data by the hypothesis that movement generation and perception of volition are separate phenomena, which can be coupled in some circumstances to give the common sense notion of voluntary movement.

5.0 How can there be (voluntary) movement without free will?

Humans do not appear to be purely reflexive organisms, simple automatons. A vast array of different movements are generated in a variety of settings. Is there an alternative to free will? Movement, in the final analysis, comes only from muscle contraction. Muscle contraction is under the complete control of the alpha motoneurons in the spinal cord. When the alpha motoneurons are active, there will be movement. Activity of the alpha motoneurons is a product of the different synaptic events on their dendrites and cell bodies. There is a complex summation of EPSPs and IPSPs, and when the threshold for an action potential is crossed, the cell fires. There are a large number of important inputs, and one of the most important is from the corticospinal tract which conveys a large part of the cortical control. Such a situation likely holds also for the motor cortex and the cells of origin of the corticospinal tract. Their firing depends on their synaptic inputs. And, a similar situation must hold for all the principal regions giving input to the motor cortex. For any cortical region, its activity will depend on its synaptic inputs. Some motor cortical inputs come via only a few synapses from sensory cortices, and such influences on motor output are clear. Some inputs will come from regions, such as the limbic areas, many synapses away from both primary sensory and motor cortices. At any one time, the activity of the motor cortex, and its commands to the spinal cord, will reflect virtually all the activity in the entire brain. Is it necessary that there be anything else? This can be a complete description of the process of movement selection, and even if there is something more -- like free will -- it would have to operate through such neuronal mechanisms (Fig. 3). A review of decision making for saccades details a similar argument.(Opris and Bruce, 2005)

Fig. 3.

Influences on the motor system that drive movement. If free will is one of those influences, its anatomy is unknown.

There have been some demonstrations that movements occur when cellular activity in specific regions of the brain achieve a certain level of firing. One such nice example is saccadic initiation in monkeys in a reaction time experiment. Saccades are initiated when single cell activity in the frontal eye field reaches a certain level; more rapid reaction times occur when the cellular activity reaches the threshold level more rapidly (Fig. 4).(Schall, 2001; Schall, 2002; Stuphorn and Schall, 2002) This has also been demonstrated in the motor cortex for limb movements.(Lecas et al., 1986) Similar results can be seen in the putamen (Lee and Assad, 2003) and the parietal reach region, a part of BA5.(Snyder et al., 2006) Moreover, electrical stimulation within a nuclear region can raise firing rates and influence behavior. Electrical stimulation within the supplementary eye field can speed up the initiation of smooth pursuit initiation.(Missal and Heinen, 2001; Missal and Heinen, 2004) Stimulation in the frontal eye field or dorsolateral prefrontal cortex can influence the direction of an upcoming saccade to be deviant from what would have been elicited from a visual clue alone.(Gold and Shadlen, 2000; Opris et al., 2005a; Opris et al., 2005b) In another situation, monkeys discriminated among eight possible directions of motion while directional signals were manipulated in visual area MT.(Salzman and Newsome, 1994) One directional signal was generated by a visual stimulus and a second signal was introduced by electrically stimulating neurons that encoded a specific direction of motion. The monkeys made a decision for one or the other signal, indicating that the signals exerted independent effects on performance and that the effects of the two signals were not simply averaged together. The monkeys, therefore, chose the direction encoded by the largest signal in the representation of motion direction, a “winner-take-all” decision process. In a similar experiment, monkeys made choices of direction of saccades; stimulation in the response field of the directional saccade in the lateral interparietal area (LIP) area increased the choices of saccades in that direction.(Hanks et al., 2006) The influence of microstimulation on cognitive function in primates has been reviewed.(Cohen and Newsome, 2004)

Fig. 4.

Diagrammatic representation of activation of neural activity and the triggering of saccadic eye movements. Activity reaches threshold at 3 different times and saccades are initiated when threshold is reached. Modified from Schall and Thompson 1999 with permission.

Using this logic, we and others postulated that it might be possible to influence decisions with transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). The phenomenon that TMS might bias motor choice was first reported by Ammon and Gandevia.(Ammon and Gandevia, 1990) Subjects were asked to move right or left hand randomly upon hearing the click of the magnetic coil. There was a bias to right hand movement with left hemisphere stimulation and to left hand movement with right hemisphere stimulation. We repeated this experiment and explored its physiology in more detail.(Brasil-Neto et al., 1992) Unfortunately, in better controlled experiments, we have been unable to reproduce these findings (Sohn et al., 2003). Such an experiment may well be possible, however.

Not only the sense of willing the movement, W in Libet’s terminology, but also the sense of the movement having occurred, M in Libet’s terminology, occurs prior to the actual movement. The awareness of W and M could well derive from the feedforward signals (corollary discharges) (Poulet and Hedwig, 2007) from the movement planning and the movement execution since all of this certainly occurs prior to movement feedback and movement feedback is not necessary anyway.(Frith, 2002; Frith, Blakemore et al., 2000)

The view that there is no such thing as free will as an inner causal agent has been advocated by a number of philosophers, scientists, and neurologists including Ryle, Adrian, Skinner and Fisher.(Fisher, 1993; Fisher, 2003) Wegner and Wheatley conclude: “Believing that our conscious thoughts cause our actions is an error based on the illusory experience of will – much like believing that a rabbit has indeed popped out of an empty hat.”(Wegner and Wheatley, 1999)

6.0 Movement genesis

The tools of neurology and neuroscience can locate and study the process movement genesis. Lesion studies can reveal situations where voluntary movements are lacking or diminished, and some of these have been noted earlier. Functional imaging studies can reveal what regions are active with movement selection.

Using blood flow PET, Deiber et al. have investigated movement selection in a series of studies. In the first study, normal subjects performed five different motor tasks consisting of moving a joystick on hearing a tone.(Deiber et al., 1991) In the control task they always pushed it forwards (fixed condition), and in four other experimental tasks the subjects had to select between four possible directions of movement depending on instructions, including one task where the choice of movement direction was to be freely chosen and random. The greatest activation was seen in this latter task with significant increases in regional cerebral blood flow most prominently in the SMA. In a second study, normal subjects were asked to make one of four types of finger movements depending on instructions.(Deiber et al., 1996) The details here were better controlled and included a rest condition. Of the numerous comparisons, the critical one for the discussion here is between the fully specified condition and the freely chosen, random movement. The anterior part of the SMA was the main area preferentially involved with the freely chosen movement. Both of these studies addressed specifically the issue of the choice of WHAT to do at a designated time.

Another aspect of movement selection is the choice of WHEN to move. This was approached by Jahanshahi et al. using PET.(Jahanshahi et al., 1995) Normal subjects, in a first task, were asked to make self-initiated right index finger extensions on average once every 3 s. A second task was externally triggered finger extension with the rate yoked to that of the self-initiated task. Greater activation of the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) was the only area that significantly differentiated the self-initiated movements from the externally triggered movements. In a follow-up PET experiment, measurements of regional cerebral blood flow were made under three conditions: rest, self-initiated right index finger extension at a variable rate of once every 2–7 s, and finger extension triggered by pacing tones at unpredictable intervals (at a rate yoked to the self-initiated movements). Compared with rest, unpredictably cued movements activated the contralateral primary sensorimotor cortex, caudal SMA and contralateral putamen. Self-initiated movements additionally activated rostral SMA, adjacent anterior cingulate cortex and bilateral DLPFC.

A similar experiment was conducted by Deiber et al. using fMRI focusing on the frontal mesial cortex.(Deiber et al., 1999) There were two types of movements, repetitive or sequential, performed at two different rates, slow or fast. Four regions of interest (pre-SMA, SMA, rostral cingulate motor area, CMAr, and caudal cingulate motor area, CMAc) were identified anatomically on a high-resolution MRI of each subject’s brain. Descriptive analysis, consisting of individual assessment of significant activation, revealed a bilateral activation in the four mesial structures for all movement conditions, but self-initiated movements were more activating than visually-triggered movements. The more complex and more rapid the movements, the smaller the difference in activation efficiency between the self-initiated and the visually triggered tasks, which indicated an additional processing role of the mesial motor areas involving both the type and rate of movements. Quantitatively, activation was more for self-initiated than for visually triggered movements in pre-SMA, CMAr and CMAc.

Stephan et al. (Stephan et al., 2002) used neuroimaging to identify structures that were activated with consciously made movements more than subconscious ones. Subjects were asked to tap their right index finger in time with different rhythmic tone sequences. One sequence was perfectly regular and others had deviations of the timing of the tones by 3, 7 and 20%. Only with the 20% variance were subjects aware of having to alter the timing of the tapping. When done at a subconscious level (3%), movement adjustments were performed employing bilateral ventral mediofrontal cortex. Awareness of change without explicit knowledge of the nature of change (7%) led to additional ventral prefrontal and premotor but not dorsolateral prefrontal activations. Only fully conscious motor adaptations (20%) showed prominent involvement of anterior cingulate and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. The authors proposed that “these results demonstrate that while ventral prefrontal areas may be engaged in motor adaptations performed subconsciously, only fully conscious motor control which includes motor planning will involve dorsolateral prefrontal cortex”. In another experiment, free selection of movement was contrasted with externally specified selection of movement.(Lau et al., 2004b) The conclusion was that the DLPFC was associated with selection of either type, but the pre-SMA was specifically associated with the free selection.

The self-initiation of movement and conscious awareness of movement appear to involve mesial motor structures. As pointed out by Paus, the mesial motor structures and the anterior cingulate cortex in particular is a place of convergence for motor control, homeostatic drive, emotion and cognition.(Paus, 2001)

It is important to recognize that movement genesis is not a strictly linear process, specifically, movement does not obligatorily occur a fixed number of ms following the onset of the BP. The initiation process may vacillate depending on the various influencing factors. As noted earlier, Libet pointed out that the upcoming movement intention might be “vetoed” after it becomes conscious.(Libet, 1985; Libet, 1999) “Conscious vetoing of a conscious intention” can occur up until the point of “no return”. The point of no return is ordinarily studied in a reaction time situation where a go stimulus is followed by a no-go stimulus, and is very close to the time of the expected movement.(Mirabella et al., 2006)

7.0 Temporary interruption of volition

A strong, single pulse TMS over the motor cortex during the reaction period of a reaction time movement can delay the execution of the movement without affecting its form.(Day et al., 1989) Delivered in the middle of a movement sequence, it will produce a temporary pause.(Berardelli et al., 1994) It is interesting that in a situation like this, the intended movement must in some way be held in a buffer until it can be implemented. With repetitive TMS over the motor cortex or SMA, the program for movement sequences can be disrupted indicating their central role in implementation of a motor program.(Gerloff et al., 1997; Gerloff et al., 1998)

As noted earlier from the experiments of Libet et al., the subjective sense of having moved precedes the actual onset of movement.(Libet, Gleason et al., 1983) This interesting, inaccurate judgment of consciousness suggests that, to some extent, the brain assumes that if it issues a motor command, the movement will be generated. In experiments where the RT is delayed with TMS over the motor cortex, the judgment of when movement occurred is delayed less than the movement itself.(Haggard and Magno, 1999) Although the authors interpreted this result as the motor cortex being downstream from the site of movement awareness, it may be more indicative of the notion that movement awareness and actual movement execution are processed by parallel pathways.

8.0 Perception of volition

There is considerable research on the physiology of perception, but no final consensus about how it works. Moreover, there is not even a primitive understanding of how the basic physiology gets translated into qualia, but that again gets into the nature of consciousness itself. The two basic ideas about perception is that a percept is created in a particular place in the brain or that a percept is created by activating a relatively large network of brain structures, which has been called the global neuronal workspace model.(Dehaene et al., 2006; Sergent et al., 2005; Sergent and Dehaene, 2004) The particular place idea would be supported by the observation using fMRI that activity only in the mid-dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (area 46) is associated with the graded ability to see a stimulus that has been rendered difficult to see with metacontrast masking.(Lau and Passingham, 2006) The more global model is supported by experiments such as an activation of parietal and frontal areas with the ability to read words compared with words that are masked.(Dehaene et al., 2001) Using EEG methods, perception seems to be associated with involvement of a wide spread network; this network becomes active approximately 270 ms after activation of primary visual areas that are active whether or not a stimulus is perceived.(Dehaene, Naccache et al., 2001; Sergent, Baillet et al., 2005) A similar experiment with somatosensory awareness shows divergence of evoked responses at about 100 ms.(Schubert et al., 2006) Electrophysiological studies suggest that binding in the networks can be demonstrated with studies of oscillations and coherence.(Mima et al., 2001; Smith et al., 2006) There is also discussion as to whether perception is all or none (Sergent and Dehaene, 2004) or whether it is graded.(Christensen et al., 2006; Dehaene, Changeux et al., 2006) The grading of perception would correlate with the magnitude of network activation. The grading of perception is carried one step further with the concept that there is a level of perception that is available to consciousness only if attention is directed to it.(Dehaene, Changeux et al., 2006; Smallwood and Schooler, 2006) The existence of this level of consciousness can be determined by probing. The idea is that what is in consciousness is determined both by bottom up processes of sensory input and top down processes of attention. A local brain event becomes a quale when it accesses a more global network.

An imaging study has investigated “agency”, the feeling of being causally involved in an action, the feeling that leads us to attribute an action to ourselves rather than to another person.(Farrer et al., 2003) For there to be agency, there has to be a match of the intentional command and movement feedback. The investigators used a device that allowed them to modify the subject’s degree of control of the movements of a virtual hand presented on a screen. During a blood-flow PET study, they compared 4 conditions: (1) a condition where the subject had a full control of the movements of the virtual hand, (2) a condition where the movements of the virtual hand appeared rotated by 25 degrees with respect to the movements made by the subject, (3) a condition where the movements of the virtual hand appeared rotated by 50 degrees, and (4) a condition where the movements of the virtual hand were produced by another person and did not correspond to the subject’s movements. In the inferior part of the parietal lobe, specifically on the right side, the less the subject felt in control of the movements of the virtual hand, the higher the level of activation. In the insula, the more the subject felt in control, the more the activation. Hence, there are activation correlates to the sense of agency.

Evidence that the parietal lobe is relevant to the sense of voluntariness comes from experiments with the Libet clock (and EEG) in five patients with parietal lobe lesions.(Sirigu et al., 2004) These patients were able to make voluntary movements with normal force although two of the patients had apraxia and one of these two also had a mild sensory disturbance. While their estimation of M was in the normal range, their estimate of W was a much smaller interval from EMG onset than normal, −55.0 ms compared with −239.2 ms. A cerebellar patient group was also investigated and their performance was normal. The parietal lobe patients also had very low amplitude or absent MRCPs. These data suggest that the parietal lobe plays a part in the awareness of voluntary action and this awareness is delayed if the parietal cortex is damaged. (The abnormal MRCP is difficult to explain since the MRCP generators are not parietal, but, as the authors speculate, the MRCP might be reduced due to abnormal interactions between frontal and parietal areas during movement initiation.)

Evidence that the insula is relevant comes from a variety of sources. In an analysis of 27 stroke patients, the symptom of anosognosia for the contralateral limb was commonly associated with damage to the posterior insula.(Karnath et al., 2005) The insula is a site of convergence of information about the physiological condition of all parts of the body, and can be considered the center for interoception.(Craig, 2003) This may help construct a sense of self.(Damasio, 2003) Indeed, the role of the insula might be to indicate the “body ownership” of a movement rather than its voluntary nature.(Tsakiris et al., 2006)

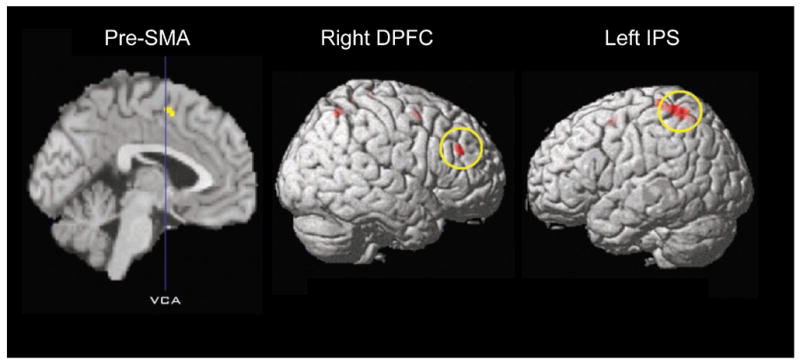

Since attention accentuates brain activity, it should be possible to help identify what areas are involved with intention by directing attention to intention itself. In the Libet clock experiment, attention is directed to intention in the W condition. Looking at the MRCPs in the W condition compared with the M condition showed a larger amplitude in the W condition.(Sirigu, Daprati et al., 2004) Using fMRI, the W condition (called the I condition in the paper) produced greater activation in the pre-SMA, right dorsal prefrontal cortex and left interparietal sulcus (Fig. 5).(Lau et al., 2004a) With connectivity analysis, the pre-SMA and prefrontal areas were correlated, but not the parietal area. The authors suggest that the pre-SMA is the critical area for the sense of intention. An alternate interpretation might be that the frontal area reflects the movement genesis and the parietal area reflects the sense of volition. Another experiment showed that attention to M compared with movement without attention yielded activation in the cingulate motor area,(Lau et al., 2006) another structure that should be involved in movement genesis. The authors noted that M was earlier in time when the CMA was more active, and that W was earlier in time when pre-SMA was more active. This suggests another difficulty in the subjective measurement of W and M, in that they depend on attention.

Fig. 5.

Regions activated with attention to intention, that is, areas activated by subjects trying to determine the onset of intending to move (W condition; called I condition in this paper) as compared with when trying to determine the movement itself (M condition). SMA is supplementary motor area, DPFC is dorsal prefrontal cortex, IPS is interparietal sulcus. Modified from Lau et al. 2004 with permission.

The timing of perception of W and M can be influenced by TMS over the pre-SMA delivered “immediately after the action” or 200 ms later.(Lau et al., 2007) This had the effect of moving the W judgment earlier in time and the M judgment later in time. This effect was time specific and did not occur with stimulation over the primary motor cortex. There are a number of conclusions. Subjective timing of events that are felt to occur prior to the movement may be influenced after the movement. This poses another problem for the method of subjective timing, but also might be consistent with the possibility that the sense of W actually does occur after the movement. Indeed, there must be a delay between any event in the real world and its perception. Perhaps the delay is sufficiently long so that the real time of W is after movement onset even if it is perceived to be before movement onset (Fig. 6). Moreover, these results further document the role of the mesial motor areas in the subjective sense of volition.

Fig. 6.

Possible timing of subjective events in comparison to measurable events in the course of making voluntary movements. This is similar to Figure 2, but the subjective events and measurable events are plotted on separate time lines. The subjective events are plotted twice, once at the time they are ascribed to in real world time and once when they might actually have occurred. The latter is only hypothetical, but is necessarily in the right direction from the ascribed times.

9.0 Conclusions

There is no evidence yet identified for free will as a force in the generation of movement, and the neurophysiology of movement is fairly advanced. Decisions must be made by the brain and these mechanisms are being understood also. Hence, it is much more likely that free will is entirely an introspection. It is a strong and virtually universal perception, but, as been illustrated here, this perception is subject to manipulation and illusion. Most evidence indicates that the neural signals that produce the perception of free will are processed in parallel with the signals that produce the movement, since the two events are subject to independent manipulation, and generally the sense of willing does precede the movement (Fig. 7). The judgment of agency has to be after the movement since it depends on the matching of intention and movement feedback. Consciousness tries to make logical sense of all the brain events in terms that it understands such as causality and the unidirectional nature of time. What is actually happening in the brain must also have its logic, but the rules may be different. Mapping the model onto brain structures, movement is likely initiated in mesial motor areas which are in turn influenced by prefrontal and limbic areas. The movement command goes to primary motor cortex with a corollary discharge to parietal area. Parietal and frontal areas maintain a relatively constant bidirectional communication. It is likely that this network of structures includes the insula. Within this network, with activation as well of the global neuronal workspace, the perception of volition is generated. The sense of agency comes from the appropriate match of volition and movement feedback, likely centered on the parietal area.

Fig. 7.

Mapping of free will model onto brain anatomy with some additional components. The top part is the same as the bottom model of Fig. 1. SMA is supplementary motor area, IPS is interparietal sulcus.

10.0 Endnotes

10.1 Implications for morality and the law

It is difficult to escape some implications of the thesis put forward here, but I will make only a brief comment. Free will exists, but it is a perception and not a force driving movement. If there is no free will as a driving force, are persons responsible for their behavior? This appears to be a difficult question, but it is really not. It is difficult only for the dualist. A person’s brain is clearly fully responsible, and always responsible, for the person’s behavior. Behavior, like all other elements of a person, is a product of that person’s genetics and experience. A person’s behavior should be able to be influenced by specific environmental interventions, such as reward and punishment. Fisher has discussed this in detail.(Fisher, 2001) In the end, if society is not happy with a person’s behavior, it is a societal decision as to what to do about it, punishment or medical remediation or something else.

10.2 What has been demonstrated

The mechanisms for the production of voluntary movement are becoming elucidated. There does not appear to be a component process for producing voluntary movement that might be called “free will” in the ordinarily sense of the word. Free will, volition, appears to be a quale that is often distorted in different neurological conditions. What has been the providence of philosophy, has now become legitimate discourse for neurology and neuroscience.

Footnotes

NOTE

As work of the US government, there is no copyright. The basic argument of this manuscript derives from a lecture at Oberlin College in 1994. I have lectured on this topic often, and written earlier versions as a syllabus for a course at the American Academy of Neurology (a pirated copy of which was posted on the internet) and for a book chapter.(Hallett, 2006) I am pleased to acknowledge helpful comments from Drs. A. Mele, S. Wise, F. Nahab, S. Pirio Richardson, M. O’Donovan, and P. Haggard.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aboitiz F, Carrasco X, Schroter C, Zaidel D, Zaidel E, Lavados M. The alien hand syndrome: classification of forms reported and discussion of a new condition. Neurol Sci. 2003;24(4):252–257. doi: 10.1007/s10072-003-0149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammon K, Gandevia SC. Transcranial magnetic stimulation can influence the selection of motor programmes. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 1990;53:705–707. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.53.8.705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baars BJ. Metaphors of consciousness and attention in the brain. Trends Neurosci. 1998;21(2):58–62. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01171-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berardelli A, Inghilleri M, Polidori L, Priori A, Mercuri B, Manfredi M. Effects of transcranial magnetic stimulation on single and sequential arm movements. Exp Brain Res. 1994;98(3):501–506. doi: 10.1007/BF00233987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berti A, Bottini G, Gandola M, Pia L, Smania N, Stracciari A, et al. Shared cortical anatomy for motor awareness and motor control. Science. 2005;309(5733):488–491. doi: 10.1126/science.1110625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohlhalter S, Goldfine A, Matteson S, Garraux G, Hanakawa T, Kansaku K, et al. Neural correlates of tic generation in Tourette syndrome: an event-related functional MRI study. Brain. 2006;129(Pt 8):2029–2037. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brasil-Neto JP, Pascual-Leone A, Valls-Solé J, Cohen LG, Hallett M. Focal transcranial magnetic stimulation and response bias in a forced-choice task. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 1992;55:964–966. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.55.10.964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown P, Thompson PD. Electrophysiological aids to the diagnosis of psychogenic jerks, spasms, and tremor. Mov Disord. 2001;16(4):595–599. doi: 10.1002/mds.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen MS, Ramsoy TZ, Lund TE, Madsen KH, Rowe JB. An fMRI study of the neural correlates of graded visual perception. Neuroimage. 2006;31(4):1711–1725. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MR, Newsome WT. What electrical microstimulation has revealed about the neural basis of cognition. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2004;14(2):169–177. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig AD. Interoception: the sense of the physiological condition of the body. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2003;13(4):500–505. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(03)00090-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick F. The Astonishing Hypothesis: The Scientific Search for the Soul. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Damasio A. Mental self: The person within. Nature. 2003;423(6937):227. doi: 10.1038/423227a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day BL, Rothwell JC, Thompson PD, Maertens de Noorhout A, Nakashima K, Shannon K, et al. Delay in the execution of voluntary movement by electrical or magnetic brain stimulation in intact man. Brain. 1989;112:649–663. doi: 10.1093/brain/112.3.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deecke L. Electrophysiological correlates of movement initiation. Rev Neurol (Paris) 1990;146(10):612–619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deecke L, Kornhuber HH. Human freedom, reasoned will, and the brain: the Bereitschaftspotential story. In: Jahanshahi M, Hallett M, editors. The Bereitschaftspotential: Movement-related Cortical Potentials. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2003. pp. 283–320. [Google Scholar]

- Dehaene S, Changeux JP, Naccache L, Sackur J, Sergent C. Conscious, preconscious, and subliminal processing: a testable taxonomy. Trends Cogn Sci. 2006;10(5):204–211. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehaene S, Naccache L, Cohen L, Bihan DL, Mangin JF, Poline JB, et al. Cerebral mechanisms of word masking and unconscious repetition priming. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4(7):752–758. doi: 10.1038/89551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deiber MP, Honda M, Ibanez V, Sadato N, Hallett M. Mesial motor areas in self-initiated versus externally triggered movements examined with fMRI: effect of movement type and rate. J Neurophysiol. 1999;81(6):3065–3077. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.6.3065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deiber MP, Ibañez V, Sadato N, Hallett M. Cerebral structures participating in motor preparation in humans: a positron emission tomography study. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1996;75:233–247. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.75.1.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deiber MP, Passingham RE, Colebatch JG, Friston KJ, Nixon PD, Frackowiak RSJ. Cortical areas and the selection of movement: a study with positron emission tomography. Experimental Brain Research. 1991;84:393–402. doi: 10.1007/BF00231461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennett DC. Consciousness Explained. Boston: Little, Brown & Co.; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Deuschl G, Koster B, Lucking CH, Scheidt C. Diagnostic and pathophysiological aspects of psychogenic tremors. Mov Disord. 1998;13(2):294–302. doi: 10.1002/mds.870130216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagleman DM, Sejnowski TJ. Motion integration and postdiction in visual awareness. Science. 2000;287(5460):2036–2038. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5460.2036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagleman DM, Tse PU, Buonomano D, Janssen P, Nobre AC, Holcombe AO. Time and the brain: how subjective time relates to neural time. J Neurosci. 2005;25(45):10369–10371. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3487-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrer C, Franck N, Georgieff N, Frith CD, Decety J, Jeannerod M. Modulating the experience of agency: a positron emission tomography study. Neuroimage. 2003;18(2):324–333. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(02)00041-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher CM. Honored guest presentation: abulia minor vs. agitated behavior. Clin Neurosurg. 1983;31:9–31. doi: 10.1093/neurosurgery/31.cn_suppl_1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher CM. Concerning mind. Can J Neurol Sci. 1993;20(3):247–253. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100048034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher CM. Alien hand phenomena: a review with the addition of six personal cases. Can J Neurol Sci. 2000;27(3):192–203. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100000834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher CM. If there were no free will. Med Hypotheses. 2001;56(3):364–366. doi: 10.1054/mehy.2000.1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher CM. The reach of neurology. Arch Neurol. 2003;60(2):173–177. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.2.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frith CD. Attention to action and awareness of other minds. Conscious Cogn. 2002;11(4):481–487. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8100(02)00022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frith CD, Blakemore S, Wolpert DM. Explaining the symptoms of schizophrenia: abnormalities in the awareness of action. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2000;31(2–3):357–363. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(99)00052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerloff C, Corwell B, Chen R, Hallett M, Cohen LG. Stimulation over the human supplementary motor area interferes with the organization of future elements in complex motor sequences. Brain. 1997;120(Pt 9):1587–1602. doi: 10.1093/brain/120.9.1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerloff C, Corwell B, Chen R, Hallett M, Cohen LG. The role of the human motor cortex in the control of complex and simple finger movement sequences. Brain. 1998;121(Pt 9):1695–1709. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.9.1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold JI, Shadlen MN. Representation of a perceptual decision in developing oculomotor commands. Nature. 2000;404(6776):390–394. doi: 10.1038/35006062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haggard P, Clark S, Kalogeras J. Voluntary action and conscious awareness. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5(4):382–385. doi: 10.1038/nn827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haggard P, Eimer M. On the relation between brain potentials and the awareness of voluntary movements. Exp Brain Res. 1999;126(1):128–133. doi: 10.1007/s002210050722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haggard P, Magno E. Localising awareness of action with transcranial magnetic stimulation. Exp Brain Res. 1999;127(1):102–107. doi: 10.1007/s002210050778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haggard P, Newman C, Magno E. On the perceived time of voluntary actions. Br J Psychol. 1999;90 (Pt 2):291–303. doi: 10.1348/000712699161413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallett M. Voluntary and involuntary movements in humans. In: Hallett M, Fahn S, Jankovic J, Lang AE, Cloninger CR, Yudofsky SC, editors. Psychogenic Movement Disorders. Neurology and Psychiatry. Philadelphia: AAN Press, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006. pp. 189–195. [Google Scholar]

- Hanks TD, Ditterich J, Shadlen MN. Microstimulation of macaque area LIP affects decision-making in a motion discrimination task. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9(5):682–689. doi: 10.1038/nn1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahanshahi M, Hallett M, editors. The Bereitschaftspotential: Movement Related Cortical Potentials. New York: Kluver Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Jahanshahi M, Jenkins IH, Brown RG, Marsden CD, Passingham RE, Brooks DJ. Self-initiated versus externally triggered movements. I. An investigation using measurement of regional cerebral blood flow with PET and movement-related potentials in normal and Parkinson’s disease subjects. Brain. 1995;118(Pt 4):913–933. doi: 10.1093/brain/118.4.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnath HO, Baier B, Nagele T. Awareness of the functioning of one’s own limbs mediated by the insular cortex? J Neurosci. 2005;25(31):7134–7138. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1590-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karp BI, Porter S, Toro C, Hallett M. Simple motor tics may be preceded by a premotor potential. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 1996;61:103–106. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.61.1.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller I, Heckhausen H. Readiness potentials preceding spontaneous motor acts: voluntary vs. involuntary control. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1990;76(4):351–361. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(90)90036-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikkert MA, Ribbers GM, Koudstaal PJ. Alien hand syndrome in stroke: a report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87(5):728–732. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsbourne M. Integrated cortical field model of consciousness. Ciba Found Symp. 1993;174:43–50. doi: 10.1002/9780470514412.ch3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumru H, Valls-Sole J, Valldeoriola F, Marti MJ, Sanegre MT, Tolosa E. Transient arrest of psychogenic tremor induced by contralateral ballistic movements. Neurosci Lett. 2004;370(2–3):135–139. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau HC, Passingham RE. Relative blindsight in normal observers and the neural correlate of visual consciousness. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(49):18763–18768. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607716103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau HC, Rogers RD, Haggard P, Passingham RE. Attention to intention. Science. 2004a;303(5661):1208–1210. doi: 10.1126/science.1090973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau HC, Rogers RD, Passingham RE. On measuring the perceived onsets of spontaneous actions. J Neurosci. 2006;26(27):7265–7271. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1138-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau HC, Rogers RD, Passingham RE. Manipulating the experienced onset of intention after action execution. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2007;19(1):81–90. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2007.19.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau HC, Rogers RD, Ramnani N, Passingham RE. Willed action and attention to the selection of action. Neuroimage. 2004b;21(4):1407–1415. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecas JC, Requin J, Anger C, Vitton N. Changes in neuronal activity of the monkey precentral cortex during preparation for movement. J Neurophysiol. 1986;56(6):1680–1702. doi: 10.1152/jn.1986.56.6.1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee IH, Assad JA. Putaminal activity for simple reactions or self-timed movements. J Neurophysiol. 2003;89(5):2528–2537. doi: 10.1152/jn.01055.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libet B. Unconscious cerebral initiative and the role of conscious will in voluntary action. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 1985;8:529–566. [Google Scholar]

- Libet B. Do we have free will? Journal of Consciousness Studies. 1999;9:47–57. [Google Scholar]

- Libet B. The timing of brain events: reply to the “Special Section” in this journal of September 2004, edited by Susan Pockett. Conscious Cogn. 2006;15(3):540–547. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libet B, Gleason CA, Wright EW, Pearl DK. Time of conscious intention to act in relation to onset of cerebral activity (readiness-potential). The unconscious initiation of a freely voluntary act. Brain. 1983;106(Pt 3):623–642. doi: 10.1093/brain/106.3.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libet B, Wright EW, Jr, Gleason CA. Readiness-potentials preceding unrestricted ‘spontaneous’ vs. pre- planned voluntary acts. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1982;54(3):322–335. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(82)90181-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacIntyre NJ, McComas AJ. Non-conscious choice in cutaneous backward masking. Neuroreport. 1996;7(9):1513–1516. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199606170-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macknik SL. Chapter 11 Visual masking approaches to visual awareness. Prog Brain Res. 2006;155:177–215. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(06)55011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macknik SL, Livingstone MS. Neuronal correlates of visibility and invisibility in the primate visual system. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1(2):144–149. doi: 10.1038/393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuhashi M, Hallett M. The timing of conscious thought into action (Abstract) Clinical Neurophysiology. 2006;117(Suppl 1):S96. [Google Scholar]

- McAuley J, Rothwell J. Identification of psychogenic, dystonic, and other organic tremors by a coherence entrainment test. Mov Disord. 2004;19(3):253–267. doi: 10.1002/mds.10707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mele AR. Free Will and Luck. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mele AR. Decision, intentions, urges and free will: Why Libet has not shown what he says he has. In: Campbell J, O’Rourke M, Shier D, editors. Explanation and Causation: Topics in Comtemporary Philosophy. Boston: MIT Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mima T, Oluwatimilehin T, Hiraoka T, Hallett M. Transient interhemispheric neuronal synchrony correlates with object recognition. J Neurosci. 2001;21(11):3942–3948. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-11-03942.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirabella G, Pani P, Pare M, Ferraina S. Inhibitory control of reaching movements in humans. Exp Brain Res. 2006;174(2):240–255. doi: 10.1007/s00221-006-0456-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missal M, Heinen SJ. Facilitation of smooth pursuit initiation by electrical stimulation in the supplementary eye fields. J Neurophysiol. 2001;86(5):2413–2425. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.5.2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missal M, Heinen SJ. Supplementary eye fields stimulation facilitates anticipatory pursuit. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92(2):1257–1262. doi: 10.1152/jn.01255.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obeso JA, Rothwell JC, Marsden CD. Simple tics in Gilles de la Tourette’s syndrome are not prefaced by a normal premovement potential. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 1981;44:735–738. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.44.8.735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obhi SS, Haggard P. Free will and free won’t. American Scientist. 2004;92:358–365. [Google Scholar]

- Opris I, Barborica A, Ferrera VP. Effects of electrical microstimulation in monkey frontal eye field on saccades to remembered targets. Vision Res. 2005a;45(27):3414–3429. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2005.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opris I, Barborica A, Ferrera VP. Microstimulation of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex biases saccade target selection. J Cogn Neurosci. 2005b;17(6):893–904. doi: 10.1162/0898929054021120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opris I, Bruce CJ. Neural circuitry of judgment and decision mechanisms. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2005;48(3):509–526. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paus T. Primate anterior cingulate cortex: where motor control, drive and cognition interface. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2(6):417–424. doi: 10.1038/35077500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirio Richardson S, Matsuhashi M, Voon V, Peckham E, Nahab F, Mari Z, et al. Timing of the sense of volition in patients with schizophrenia (Abstract) Clinical Neurophysiology. 2006;117(Suppl 1):S97. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.574472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulet JF, Hedwig B. New insights into corollary discharges mediated by identified neural pathways. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30(1):14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salzman CD, Newsome WT. Neural mechanisms for forming a perceptual decision. Science. 1994;264(5156):231–237. doi: 10.1126/science.8146653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scepkowski LA, Cronin-Golomb A. The alien hand: cases, categorizations, and anatomical correlates. Behav Cogn Neurosci Rev. 2003;2(4):261–277. doi: 10.1177/1534582303260119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schall JD. Neural basis of deciding, choosing and acting. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2(1):33–42. doi: 10.1038/35049054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schall JD. The neural selection and control of saccades by the frontal eye field. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2002;357(1424):1073–1082. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2002.1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert R, Blankenburg F, Lemm S, Villringer A, Curio G. Now you feel it--now you don’t: ERP correlates of somatosensory awareness. Psychophysiology. 2006;43(1):31–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2006.00379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Searle JR. How to study consciousness scientifically. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1998;353(1377):1935–1942. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1998.0346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sergent C, Baillet S, Dehaene S. Timing of the brain events underlying access to consciousness during the attentional blink. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(10):1391–1400. doi: 10.1038/nn1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sergent C, Dehaene S. Neural processes underlying conscious perception: experimental findings and a global neuronal workspace framework. J Physiol Paris. 2004;98(4–6):374–384. doi: 10.1016/j.jphysparis.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibasaki H, Hallett M. Electrophysiological studies of myoclonus. Muscle Nerve. 2005;31(2):157–174. doi: 10.1002/mus.20234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirigu A, Daprati E, Ciancia S, Giraux P, Nighoghossian N, Posada A, et al. Altered awareness of voluntary action after damage to the parietal cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7(1):80–84. doi: 10.1038/nn1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smallwood J, Schooler JW. The restless mind. Psychol Bull. 2006;132(6):946–958. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.6.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith ML, Gosselin F, Schyns PG. Perceptual moments of conscious visual experience inferred from oscillatory brain activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(14):5626–5631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508972103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder LH, Dickinson AR, Calton JL. Preparatory delay activity in the monkey parietal reach region predicts reach reaction times. J Neurosci. 2006;26(40):10091–10099. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0513-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohn YH, Kaelin-Lang A, Hallett M. The effect of transcranial magnetic stimulation on movement selection. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74(7):985–987. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.7.985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spence SA, Crimlisk HL, Cope H, Ron MA, Grasby PM. Discrete neurophysiological correlates in prefrontal cortex during hysterical and feigned disorder of movement. Lancet. 2000;355(9211):1243–1244. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02096-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan KM, Thaut MH, Wunderlich G, Schicks W, Tian B, Tellmann L, et al. Conscious and subconscious sensorimotor synchronization--prefrontal cortex and the influence of awareness. Neuroimage. 2002;15(2):345–352. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stetson C, Cui X, Montague PR, Eagleman DM. Motor-sensory recalibration leads to an illusory reversal of action and sensation. Neuron. 2006;51(5):651–659. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuphorn V, Schall JD. Neuronal control and monitoring of initiation of movements. Muscle Nerve. 2002;26(3):326–339. doi: 10.1002/mus.10158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JL, McCloskey DI. Triggering of preprogrammed movements as reactions to masked stimuli. J Neurophysiol. 1990;63(3):439–446. doi: 10.1152/jn.1990.63.3.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JL, McCloskey DI. Selection of motor responses on the basis of unperceived stimuli. Exp Brain Res. 1996;110(1):62–66. doi: 10.1007/BF00241375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terada K, Ikeda A, Nagamine T, Shibasaki H. Movement-related cortical potentials associated with voluntary muscle relaxation. Electromyography and Clinical Neurophysiology. 1995a;95:335–345. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(95)00098-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terada K, Ikeda A, Van Ness PC, Nagamine T, Kaji R, Kimura J, et al. Presence of Bereitschaftspotential preceding psychogenic myoclonus: clinical application of jerk-locked back averaging. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 1995b;58:745–747. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.58.6.745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toma K, Matsuoka T, Immisch I, Mima T, Waldvogel D, Koshy B, et al. Generators of movement-related cortical potentials: fMRI-constrained EEG dipole source analysis. Neuroimage. 2002;17(1):161–173. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toro C, Torres F. Electrophysiological correlates of a paroxysmal movement disorder. Ann Neurol. 1986;20(6):731–734. doi: 10.1002/ana.410200614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsakiris M, Hesse MD, Boy C, Haggard P, Fink GR. Neural Signatures of Body Ownership: A Sensory Network for Bodily Self-Consciousness. Cereb Cortex. 2006 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhl131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuilleumier P, Chicherio C, Assal F, Schwartz S, Slosman D, Landis T. Functional neuroanatomical correlates of hysterical sensorimotor loss. Brain. 2001;124(Pt 6):1077–1090. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.6.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegner DM. The Illusion of Conscious Will. Cambridge: MIT Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wegner DM. The mind’s best trick: how we experience conscious will. Trends Cogn Sci. 2003;7(2):65–69. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(03)00002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegner DM. Precis of the illusion of conscious will. Behav Brain Sci. 2004;27(5):649–659. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x04000159. discussion 659–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegner DM, Wheatley T. Apparent mental causation. Sources of the experience of will. Am Psychol. 1999;54(7):480–492. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.7.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeman A. Consciousness. Brain. 2001;124(Pt 7):1263–1289. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.7.1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeman A. What in the world is consciousness? Prog Brain Res. 2005;150:1–10. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(05)50001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeuner KE, Shoge RO, Goldstein SR, Dambrosia JM, Hallett M. Accelerometry to distinguish psychogenic from essential or parkinsonian tremor. Neurology. 2003;61(4):548–550. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000076183.34915.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]